1. Introduction

1.1. Dual Disorders

Dual disorders (DD) are characterized as the coexistence of at least one substance use disorder (SUD) with another mental illness, where frequently, the mental illnesses involved belong to psychotic and affective clinical categories [

1]. The initial recognition of dual disorders dates back to the 1980s, with their frequent identification beginning in the 1990s. Since then, various definitions have emerged, yet a universally accepted, unambiguous definition remains elusive. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines

dual disorder as "The co-occurrence in the same individual of a psychoactive substance use disorder and another psychiatric disorder," reflecting the complexity and the overlapping nature of these conditions [

2,

3]. DDs present a formidable challenge for healthcare professionals, primarily due to the complex and variable interaction between psychoactive substances and psychiatric disorders. The intricacy of this interaction is amplified by the diverse effects of different substances and the wide range of mental disorders, each impacting clinical outcomes in distinct ways. This comorbidity also introduces significant behavioral complexities in patients, adding layers to the already intricate task of clinical management. Adding to the complexity is the bidirectional causality inherent in DDs. Substance misuse can lead to the development of mental illness, while mental illness can trigger substance misuse. Furthermore, there is a dynamic and mutual aggravation between the two disorders, with each potentially worsening the severity and progression of the other [

4]. Three potential situations can be contemplated:

drug use can induce individuals to undergo one or more symptoms of a mental health disorder, either of a short-lived nature (e.g., amphetamine-induced psychosis) or by triggering an underlying long-term mental disorder (e.g., cannabis and schizophrenia);

mental disorders might prompt drug use as a means to alleviate the symptoms associated with the mental disorder (e.g., using amphetamines to alleviate symptoms of depression);

both the issue of substance use and the presence of a mental health disorder may stem from shared factors, such as brain deficits, genetic susceptibility, and early exposure to stress or trauma [

5].

Furthermore, the following issues are widely acknowledged in research and clinical practice and should be emphasized when discussing the topic. Firstly, the combination of substance use and mental health disorders often leads to serious social, psychological and physical complications. Consequently, psychiatric comorbidity significantly contributes to the global burden of diseases, particularly among vulnerable population groups. Secondly, individuals with comorbid disorders experience poorer diagnosis, reduced access to care, and lower compliance with treatment [

5].

Although the complexity of this condition is clear, the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), does not provide specific diagnostic criteria for DDs as a co-occurring condition [

6]. The lack of standardized definitions and diagnostic criteria for DD in authoritative texts like the DSM-5 thus hinders the accurate determination of its prevalence.

1.2. Dual Disorders: what treatments are available?

Various studies document the rising prevalence of Dual Disorders [

7], wherein social changes and external factors, such as the COVID pandemic [

8] and environmental changes [

9], can additionally serve as triggering elements. Among the psychopathological effects associated with substance use, psychosis stands out as particularly significant, especially when related to the use cannabis [

10] and of new/novel psychoactive substances (NPS) [

11,

12,

13]. Indeed, many NPS can trigger psychotic symptoms, leading to a condition known as

substance-induced psychosis. This condition, recognized and diagnosed according to the DSM-5, require that the psychotic symptoms be transient and directly linked to the effects of the substance used. This condition is defined by the temporal nature of these symptoms, indicating that they are not expected to persist over a prolonged period [

6,

11]. In real-world clinical settings, the progression of symptoms in cases of substance-induced psychosis can be gradual, making a clear distinction between this condition and primary psychotic disorders challenging and often not practically useful.

In such scenarios, where definitive guidelines are absent, clinicians are required to base their medication choices on careful clinical observations and the specific characteristics of each individual case. This should make us understand the need to identify specific effective treatments in the context of a dual disorder.

In this regard, real-world studies, including observational research, play a vital role in comprehending the effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of medications. They also help identify factors that influence treatment response within diverse patient populations beyond controlled clinical trial environments. This encompasses specific patient groups such as the elderly, pediatric patients, or those with comorbid medical conditions or substance use disorders. These studies aim to evaluate the efficacy and safety of medications in these diverse groups. Real-world investigations focusing on the use of antipsychotics in patients with comorbid substance use are still limited but steadily expanding. Initial studies have indicated that atypical antipsychotics like clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine have demonstrated effectiveness in managing psychotic symptoms and reducing substance use in individuals with dual diagnoses [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Nevertheless, subsequent investigations have produced varied results, suggesting that the efficacy of treatment may be impacted by individual patient attributes and the specific subtype of substance use disorder [

19,

20]. This approach emphasizes the importance of nuanced clinical judgment and individualized patient care in the management of these complex conditions.

1.3. The potential role of brexpiprazole in Dual Disorders

As previously mentioned, the utilization of atypical antipsychotics can be particularly beneficial in DD, given their dual efficacy in addressing both psychotic and affective symptoms. This characteristic makes them a versatile option for treating conditions where both sets of symptoms are present or intertwined [

3,

21].

Brexpiprazole, classified as a third-generation antipsychotic, is characterized by its partial agonist activity at D2 receptors, a defining feature of its pharmacological profile within this class of medications. Due to its partial agonist action at D2 receptors, brexpiprazole can modulate dopaminergic activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), thus enhancing dopaminergic neurotransmission at low doses, while, conversely, at higher doses acting to block dopaminergic activity [

22]. Within the therapeutic dosage range, brexpiprazole binds to 59–75% of dopaminergic receptors, a proportion similar to older-generation antipsychotics. This substantiates its efficacy in addressing positive psychotic symptoms [

23].

Concerning the D2 receptors, brexpiprazole exhibits an intrinsic activity level similar to cariprazine or aripiprazole, indicating that it is predominantly antagonistic. However, compared to both older-generation antipsychotics and aripiprazole, it exhibits a lower incidence of adverse effects (AE) such as akathisia, nausea, or vomiting [

24].

Indeed, brexpiprazole receptor profile renders it a highly manageable medication, characterized by a low incidence of side effects: this molecule exhibits a significant antagonistic action at 5HT

2A receptors, aligning it closely with the pharmacodynamic properties typically associated with second-generation antipsychotics [

22]. This makes it more suitable for extended use, potentially reducing the risk of hyperprolactinemia, weight gain, insomnia, nausea/vomiting, or restlessness. Therefore, could potentially aid in the patients' reintegration into society [

25].

Additionally, brexpiprazole demonstrates partial agonist activity at the 5HT

1A receptor and functions as an antagonist at the α

1 receptor, thus resulting in a significantly reduced incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and akathisia [

22]. Finally, the partial agonist activity of brexpiprazole at the 5HT

1A and 5HT

7 receptors also imparts beneficial effects on cognitive function, mood and anxiety [

26,

27,

28].

As a result, Brexpiprazole’s pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile, on one hand, holds the promise of enhancing the effectiveness of schizophrenia treatment in dimensions where previous antipsychotics were not sufficiently effective, including negative, depressive, or cognitive symptoms [

29]. On the other hand, it also be beneficial in the treatment of mood disorders, often associated with substance abuse issues [

29].

1.4. Aim of the study

In light of the foregoing, the main objective of our research is to assess the efficacy of brexpiprazole in patients with schizophrenia comorbid with alcohol and/or substance use disorder (AUD/SUD). Secondarily, this study will address the safety and tolerability of Brexpiprazole in schizophrenic patients with concurrent AUD/SUD, focusing on the risk of side effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment Centers

In this prospective, multicentric, real-world study, a total of eighteen patients (14 males and 4 females; mean age 30.4 ± 8.0) diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder (DSM-5) [

6] and comorbid AUD/SUD (DSM-5) [

6] were consecutively recruited from several Italian mental health facilities. The coordination center was the Hospital Psychiatric Diagnostic and Treatment Service of the University Hospital S.S. Annunziata in Chieti. Other centers involved were the Inpatient Psychiatric Center of Villa Maria Pia in Rome, the Day Hospital of Psychiatry and Drug Dependence of the University General Hospital ‘A. Gemelli’ in Rome and the Psychiatry Outpatient Clinics at the University Hospital ‘San Luigi Gonzaga’ in Turin.

The Hospital Psychiatric Diagnostic and Treatment Service of the University Hospital S.S. Annunziata in Chieti is a specialized unit dedicated to the assessment and treatment of patients with psychiatric disorders, presenting an acute episode of illness. Patients are admitted receiving a comprehensive range of interventions, including accurate diagnosis and implementation of personalized treatment plans. The staff may include psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses and other mental health professionals. Interventions may involve pharmacological therapies, in-depth psychiatric assessments and, especially, continuous patient monitoring.

The Inpatient Psychiatric Center of Villa Maria Pia in Rome is a specialized psychiatric treatment center designed for post-acute patients, offering a 30-day hospitalization period, extendable to a maximum of 60 days. Post-acute patients are those with elevated care requirements necessitating targeted interventions to stabilize their clinical condition following an acute episode of illness. This includes individuals discharged from the hospital psychiatric diagnostic and treatment service, or, in less severe cases than those admitted to the hospital, individuals still in need of inpatient care. The facility focuses on medication monitoring and the establishment of a medium- to long-term therapeutic program.

The Day Hospital of Psychiatry and Drug Dependence of the University General Hospital ‘A. Gemelli’ in Rome and the Psychiatry Outpatient Clinics at the University Hospital ‘San Luigi Gonzaga’ in Turin engage in a range of activities aimed at the assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and care of individuals with mental health disorders and substance use disorder who do not require continuous hospitalization monitoring. These centers typically comprise a multidisciplinary team of professionals, including psychiatrists, psychologists and nurses. Psychiatrists conduct thorough clinical assessments to diagnose various mental health conditions. This involves interviewing patients, reviewing medical histories, and employing standardized assessment tools. Additionally, these professionals prescribe and manage medications to address psychiatric symptoms, evaluating their effectiveness and monitoring any side effects.

2.2. Study Design and Treatment Information

The study focused on a total of 18 subjects with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum and comorbid AUD/SUD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) [

6]. Subjects enrolled were carefully evaluated by qualified psychiatrists, investigating the previously documented history of the disease and the treatment history.

Patients included in the study who had not been previously treated with antipsychotic drugs or had been free of antipsychotic medication for a minimum of 2 weeks were initiated on Brexpiprazole, following the recommended titration from 1 mg once daily to adjustment to 2–4 mg once daily, based on the clinical response. Instead, if they were on other antipsychotic medication, patients underwent a cross-tapering process with Brexpiprazole. Once the appropriate dose for each patient was reached (based on clinical progress and the clinician's decision), the regimen was maintained for a duration of one month.

The eligibility criteria for patients were as follows: age between 18 and 65 years, with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder and concurrent AUD/SUD. Patients with ECG alterations (e.g. QTc > 450 msec), AUD/SUD in remission (more than 3 months without symptoms), acute intoxication from alcohol and substances or with severe suicidal ideation were excluded from the study. Patients were also excluded if they were pregnant or lactating and if they had a severe physical illness or evidence of mental illness severely interfering with their cognitive capacity.

2.3. Study Procedures

Anamnestic data were collected at baseline (T0), while psychometric assessments were collected at T0 and one month (T1) after treatment beginning. Psychiatric symptoms were evaluated using Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [

30] and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) [

31] scores. The level of craving for alcohol and/or substances was evaluated by a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS) [

32], that assesses craving from 0 (indicating no craving) to 10 (representing the most intense craving as perceived by the patient). Furthermore, quality of life (Short Form Health Survey 36/SF-36) [

33] as well as alcohol and substance related aggressiveness (Modified Overt Aggression Scale/MOAS) [

34] were assessed.

Moreover, a qualified psychiatrist carefully evaluated adverse events related to brexpiprazole administration and reported in the patient medical records.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Windows version 25. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine whether the data were normally distributed. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to study matched samples. The quantitative parameters were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and the qualitative parameters as number and percentage per class. The significance level was set for p < 0.05.

2.5. Ethics

All the subjects enrolled, after receiving detailed information regarding the characteristics of the drug, the prescribed dosage schedule, and the possible side effects, provided written consent with full awareness and understanding. Moreover, patients were made aware of the option to revoke their consent at any given moment.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (protocol n. 7/09-04-2015), local institutional review boards and the national regulatory authorities in accordance with local requirements. It was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent revisions.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 18 subjects were enrolled (M: 14/F: 4; Mean age: 30.4 ± 8.0) and a comprehensive presentation of their sociodemographic and clinical information is detailed in

Table 1.

The most common psychiatric diagnosis within our sample was substance-induced psychosis (n=12; 66.6 %), followed by schizoaffective disorder (n=6; 33.3 %); meanwhile the prevailing coexisting diagnosis was personality disorder (n=4; 22.2 %).

Concerning the diagnoses of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and substance use disorder (SUD), the predominant substances involved were ranked as follows: cocaine (n=9; 50%), alcohol (n=8; 44.4%), cannabis (n=7; 38.9%), methamphetamine (n=1; 5.6%) and New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) (n=1; 5.6%). Significantly, a substantial proportion of the participants were characterized as polysubstance users (n=8; 44.4 %), emphasizing the gravity of the patient population investigated in this study.

Regarding pharmacological treatment, 13 subjects (72.2 %) were antipsychotic drug-free, so they were immediately initiated on brexpiprazole. Conversely, 5 patients (27.8 %) were already on antipsychotics therapy, therefore they underwent a cross-tapering process with brexpiprazole. Specifically, 2 participants (11.1%) were receiving Olanzapine ranging from 15 to 20 mg/day, 2 (11.1%) were using Promazine ranging from 40 to 100 mg/day, and 1 (5.5%) was undergoing treatment with Quetiapine at a dosage of 100 mg/day.

In terms of other medication prescribed apart for brexpiprazole, 7 patients (38.9 %) were taking antidepressants; in particular, 3 patients (16.7 %) were taking Trazodone ranging from 50 to 220 mg/day, 2 (11.1 %) were using Sertraline 50 mg/day, 1 (5.5 %) was on Paroxetine 20 mg/day, and 1 (5.5 %) was undergoing therapy with Vortioxetine 10 mg/day.

Furthermore, in conjunction with brexpiprazole therapy, 13 patients (72.2 %) were taking mood stabilizers as follows: 4 (22.2 %) were receiving Valproate at a dosage ranging from 600 to 1000 mg/day, 1 (5.5 %) was using Lamotrigine 300 mg/day, 4 (22.2 %) were undergoing treatment with Gabapentin at a dosage ranging from 900 to 1600 mg/day, 2 (11.1 %) were using Pregabalin at a dosage ranging from 150 to 450 mg/day, 1 (5.5 %) was receiving Lithium sulfate 83 mg/day and 1 (5.5 %) was receiving Lithium carbonate 600 mg/day.

Relating to the treatment with benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, the main molecules that patients were taking, in addition to brexpiprazole, were as follows: Delorazepam ranging from 3 to 10 mg/day (n=3; 16.7 %), Diazepam ranging from 7 to 22 mg/day (n=3; 16.7 %) and Zolpidem 10 mg/day (n=1; 5.5 %).

Finally, 2 subjects (11.1 %) were taking other drugs than those previously mentioned, in addition to brexpiprazole; precisely 1 patient (5.5 %) was taking Methadone 55 mg/die and 1 patient (5.5 %) was using Baclofen 35 mg/die.

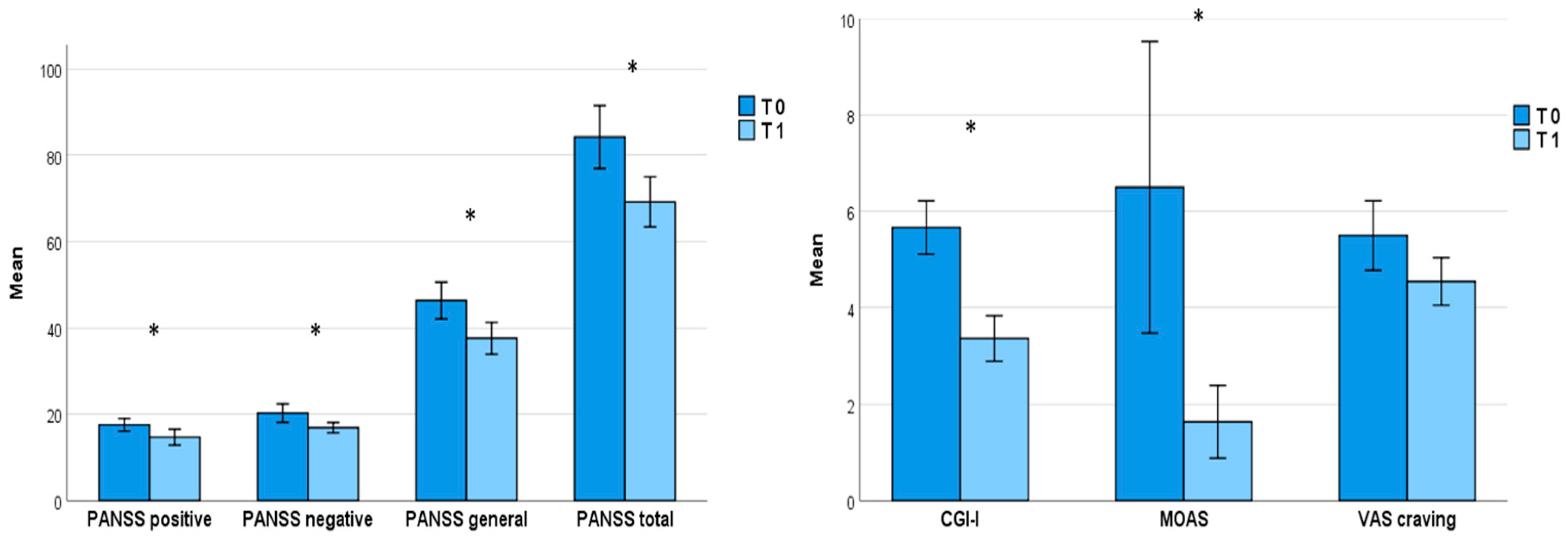

3.2. Changes in psychopathological domains from baseline to one-month follow-up

One month of treatment with brexpiprazole, at an average dosage of 2 mg once daily (2.3 ± 1.1), proved effective in reducing the overall psychopathological burden, as evidenced by a significant decrease in PANSS total score (T0=84.2 ± 31.0, T1=67.0 ± 18.9;

p=0.004) as well as its subscales (

Positive symptoms: T0=17.6 ± 6.2, T1=14.7 ± 5.9,

p=0.012;

Negative symptoms: T0=20.3 ± 9.1, T1=16.0 ± 4.7,

p= 0.032;

General psychopathology: T0=46.3 ± 18.1, T1=37.0 ± 11.2,

p=0.006); similarly, both CGI-I total score (T0=5.7 ± 1.9, T1=3.4 ± 1.6,

p=0.042) and MOAS total score (T0=6.7 ± 8.9, T1=1.6 ± 2.5,

p=0.012) improved (

Table 2;

Figure 1). Nevertheless, despite the decrease in VAS scale scores from baseline (5.5 ± 2.4) to T1 (4.5 ± 1.6), the reduction in substance craving did not reach statistical significance (

Table 2;

Figure 1).

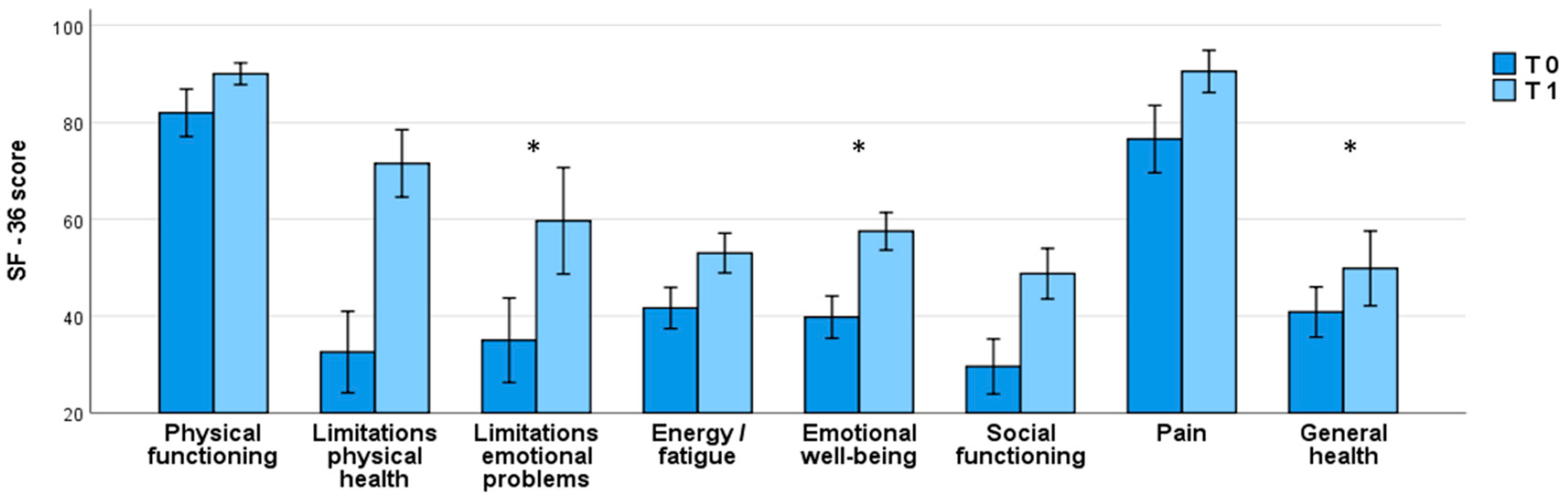

3.3. Changes in global health condition from baseline to one-month follow-up

A notable self-reported enhancement in global health condition was noted one month after initiating brexpiprazole treatment, as highlighted by the significant increase in some of SF-36 subscales, e.g.

Limitations due to emotional problems: T0=35.0 ± 37.0, T1=59.7 ± 34.7,

p=0.047;

Emotional well-being: T0=39.8 ± 18.5, T1=57.5 ± 12.3,

p=0.015 and

General health: T0=40.8 ± 22.0, T1=49.8 ± 24.4,

p=0.018 (

Table 2;

Figure 2).

3.4. Safety and Tolerability of brexpiprazole

The study observed that brexpiprazole demonstrated overall safety and good tolerance. In fact, there were no dropouts due to drug-related side effects.

However, we observed a substantial non-adherence rate to the treatments, with 38,9 % (7 out of 18) of patients discontinuing prior to T1. Among these, 14.2 % (1 patient) relapsed into substance use, 14.2 % (1 patient) experienced low effectiveness on psychiatric disorder, and 71.4% (5 patients) dropped out for non-adherence to drug therapy. The observed high attrition rate is likely due to the inherent nature of the study (outpatients setting, involving subjects with severe dual diagnoses).

4. Discussion

This Italian study, conducted on a cohort of inpatients with schizophrenia comorbid with AUD/SUD, presents initial evidence for the use of the antipsychotic brexpiprazole in treatment of schizophrenia comorbid with AUD/SUD, showing its efficacy, safety and limitations of its use in this population.

Brexpiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic medication that is used for the treatment of schizophrenia and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder. It has a unique pharmacological profile, and its use in patients with psychotic symptoms and comorbid addiction presents both potential benefits and challenges. Specifically, in this population low dosage brexpiprazole (up to 2mg/day) demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of psychotic symptoms (both positive and negative) and aggressiveness and provided benefits for individuals with potential comorbid mood-related symptoms. Apart for drug efficacy, brexpiprazole-related enhancement of quality of life was determined in terms of psychopathology and general health, possibly due to a low impact on metabolic parameters, including weight gain and lipid profile, and a typical once-daily administration. Indeed, no dropouts due to drug-related side effects were recorded. This data is consistent with recent systematic reviews reporting brexpiprazole as a promising new drug in the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia for both acute exacerbation and maintenance treatment, and, compared to currently used antipsychotics, for a better tolerability and safety profile [

3,

21].

Unfortunately, in this study the VAS scale for craving, despite the reduction, did not reach a statistical significance. The observed data can be elucidated by the inherent characteristics of the sample and the particular features of AUD/SUD, which may have influenced adherence to drug therapy (5 out of 7 patients discontinued due to non-adherence to drug therapy), as evidenced by various studies on AUD/SUD [

35]. Furthermore, assessing the craving for substances poses a persistent challenge as it fluctuates throughout the day and is often influenced by contextual and environmental factors. A visual analogue scale may not be adequately comprehensive to capture this phenomenon. Indeed, an Italian observational study including 85 adult patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia with either comorbid SUD (55.8%) or non-SUD (44.2%) treated with brexpiprazole 4 mg/day for 6 months showed improvements over the course of the study for CGI-S, BPRS, and PANSS in both SUD and non-SUD groups and the entire sample, and in the SUD group a statistically significant reduction of substance craving [

36]. Supporting this, an animal study from Nickols et al (2023), offered preclinical support for the effectiveness of brexpiprazole as a dopamine partial agonist in modulating behaviors dependent on dopamine during both opioid use and withdrawal, e.g., pathological drug-seeking behavior and other symptoms associated with opioid withdrawal following drug discontinuation [

37].

4.1. Future challenges

In this context, it is important to make some considerations related to the need in DD populations of an integrated treatment approach that addresses both the psychotic symptoms and addiction, being crucial the collaboration between mental health and addiction professionals. Treatment plans should be tailored to the individual's specific needs, considering the type and severity of psychotic symptoms, the substances involved, and other relevant factors, e.g. environmental, familiar, social, personal, medical, etc. In consideration of the risk of relapse, substance use can complicate the treatment course, thus, close monitoring of both mental health symptoms and substance use are integral components of care. Moreover, providing education to patients about both the medication, its potential side effects, and the importance of adherence, and the prevention of relapse in substance use is essential for treatment success. In fact, individuals with comorbid conditions may encounter difficulties in adhering to medication; in this context, brexpiprazole is typically given once daily, ensuring the essential consistency required for its effectiveness. In this regard, educating patients about the potential risks and benefits of brexpiprazole, along with the significance of adhering to the medication regimen, can improve treatment outcomes.

Ultimately, there is a need to extend and broaden the scope of rehabilitation endeavors and psychosocial interventions, transitioning them beyond residential facilities to encompass the community. This entails the establishment of an array of mental health services within the community that actively engage both patients and their family members.

4.2. Limitations and strengths of the study

Our research encountered various limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small, necessitating an expansion to enhance the reliability of our findings. Additionally, the absence of comparison groups, such as individuals treated with antipsychotics other than brexpiprazole or a placebo, hinders a comprehensive analysis. Moreover, the duration of the study is relatively limited, requiring further follow ups; moreover, currently, long-term data on the safety and efficacy of brexpiprazole are still evolving, and its use in certain populations may require careful considerations. The utilization of open-label studies introduces the potential for biased results and restricts the applicability of our conclusions. Furthermore, the data analysis lacked granularity regarding gender.

However, our work has important strengths. First of all, the multicentricity of our study, conducted in several hospitals in various Italian regions. Another aspect of being underlined is the non-randomized nature of the study leads to a narrowing of the gap with clinical reality, representing a real-word situation.

5. Conclusions

This research provides a preliminary analysis of the efficacy of brexpiprazole in treating schizophrenia concurrent with alcohol and substance use disorder (AUD/SUD). The results indicate a significant reduction in psychopathological burden, improvement in quality of life, and a decrease in substance-related aggression after one month of brexpiprazole treatment. Although a reduction in substance craving was observed, it did not reach statistical significance. Non-adherence rates highlight the challenges in managing this population, underscoring the need for personalized treatment strategies and integrated mental health services. The study offers initial evidence supporting the efficacy of brexpiprazole in this complex patient cohort, emphasizing the importance of extended follow-ups and further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., C.S., and M.A.; methodology, M.G., D.C.F.; software, D.C.F., C.C.; formal analysis, D.C.F.; investigation, C.C., C.S., M.A., V.R., P.M., D.P.M.P, P.T., L.C.; data curation, C.C., P.T., D.P.M.P.; C.S., C.C., M.A., P.T.; original draft preparation, C.C., M.A; writing—review and editing, C.S., C.C., M.A., P.T.; supervision, M.G., P.M., D.N.M., V.R.; project administration, G.M., C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics Committee of D'ANNUNZIO UNIVERSITY OF CHIETI–PESCARA (protocol n. 7/09-04-2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

M.G. has been a consultant and/or a speaker and/or has received research grants from Angelini, Doc Generici, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfiser, Servier, Recordati. All the other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adan and I. Benaiges, “Comorbidity between Substance Use Disorder and Severe Mental Illness,” in Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse, Elsevier, 2016, pp. 258–268. [CrossRef]

- K. Hryb, R. Kirkhart, and R. Talbert, “A Call for Standardized Definition of Dual Diagnosis,” Psychiatry (Edgmont), vol. 4, no. 9, p. 15, Sep. 2007, Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC2880934/.

- G. Martinotti et al., “Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs in Dual Disorders: Current Evidence for Clinical Practice.,” Curr Pharm Des, vol. 28, no. 27, pp. 2241–2259, 2022. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), “Guideline scope Severe mental illness and substance misuse (dual diagnosis): community health and social care services Topic.”.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), “Co-morbid substance use and mental disorders in Europe: a review of the data EMCDDA PAPERS”.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-5) 5th ed., 5th ed. Washington DC, 2013.

- Mårtensson S, Düring SW, Johansen KS, Tranberg K, Nordentoft M. Time trends in co-occurring substance use and psychiatric illness (dual diagnosis) from 2000 to 2017 - a nationwide study of Danish register data. Nord J Psychiatry. 2023 May;77(4):411-419. Epub 2022 Oct 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinotti G, Alessi MC, Di Natale C, Sociali A, Ceci F, Lucidi L, Picutti E, Di Carlo F, Corbo M, Vellante F, Fiori F, Tourjansky G, Catalano G, Carenti ML, Incerti CC, Bartoletti L, Barlati S, Romeo VM, Verrastro V, De Giorgio F, Valchera A, Sepede G, Casella P, Pettorruso M, di Giannantonio M. Psychopathological Burden and Quality of Life in Substance Users During the COVID-19 Lockdown Period in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Sep 3;11:572245. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MacFarlane EK, Shakya R, Berry HL, Kohrt BA. Implications of participatory methods to address mental health needs associated with climate change: ‘photovoice’ in Nepal. BJPsych International. 2015;12(2):33-35. [CrossRef]

- Ricci V, Ceci F, Di Carlo F, Lalli A, Ciavoni L, Mosca A, Sepede G, Salone A, Quattrone D, Fraticelli S, Maina G, Martinotti G. Cannabis use disorder and dissociation: A report from a prospective first-episode psychosis study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Dec 1;229(Pt A):109118. Epub 2021 Oct 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Martinotti, L. De Risio, C. Vannini, F. Schifano, M. Pettorruso, and M. Di Giannantonio, “Substance-related exogenous psychosis: a postmodern syndrome.,” CNS Spectr, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 84–91, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Orsolini, S. Chiappini, D. Papanti, D. De Berardis, J. M. Corkery, and F. Schifano, “The Bridge Between Classical and ‘Synthetic’/Chemical Psychoses: Towards a Clinical, Psychopathological, and Therapeutic Perspective.,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 10, p. 851, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Corazza O, Valeriani G, Bersani FS, Corkery J, Martinotti G, Bersani G, Schifano F. "Spice," "kryptonite," "black mamba": an overview of brand names and marketing strategies of novel psychoactive substances on the web. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014 Oct-Dec;46(4):287-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. W. J. Machielsen, D. J. Veltman, W. Van Den Brink, and L. De Haan, “The effect of clozapine and risperidone on attentional bias in patients with schizophrenia and a cannabis use disorder: An fMRI study,” J. Psychopharmacol., vol. 28, no. 7, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Brunette et al., “A randomized trial of clozapine versus other antipsychotics for cannabis use disorder in patients with schizophrenia,” J. Dual Diagn., vol. 7, no. 1–2, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Brunette, R. E. Drake, H. Xie, G. J. McHugo, and A. I. Green, “Clozapine use and relapses of substance use disorder among patients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders,” Schizophr. Bull., vol. 32, no. 4, 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. Schnell et al., “Ziprasidone versus clozapine in the treatment of dually diagnosed (DD) patients with schizophrenia and cannabis use disorders: A randomized study,” Am. J. Addict., vol. 23, no. 3, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kim, D. Kim, and S. R. Marder, “Time to rehospitalization of clozapine versus risperidone in the naturalistic treatment of comorbid alcohol use disorder and schizophrenia,” Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry, vol. 32, no. 4, 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Beresford, J. Buchanan, E. B. Thumm, C. Emrick, D. Weitzenkamp, and P. J. Ronan, “Late Reduction of Cocaine Cravings in a Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Aripiprazole vs Perphenazine in Schizophrenia and Comorbid Cocaine Dependence,” J. Clin. Psychopharmacol., vol. 37, no. 6, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Van Nimwegen, L. De Haan, N. J. M. Van Beveren, M. Van Der Helm, W. Van Den Brink, and D. Linszen, “Effect of olanzapine and risperidone on subjective well-being and craving for cannabis in patients with schizophrenia or related disorders: A double-blind randomized controlled trial,” Can. J. Psychiatry, vol. 53, no. 6, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Orzelska-Górka J, Mikulska J, Wiszniewska A, Biała G. New Atypical Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia and Depression. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 13;23(18):10624. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stephen M. Stahl, Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications, Fourth edition. 2013.

- Wong D.F., Raoufinia A., Bricmont P., Brašić J.R., McQuade R.D., Forbes R.A., Kikuchi T., Kuwabara H. An open-label, positron emission tomography study of the striatal D2/D3 receptor occupancy and pharmacokinetics of single-dose oral brexpiprazole in healthy participants. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021;77:717–725. [CrossRef]

- Stahl S.M. Mechanism of action of cariprazine. CNS Spectrums. 2016;21:123–127. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe Y, Yamada S, Otsubo T, Kikuchi T. Brexpiprazole for the Treatment of Schizophrenia in Adults: An Overview of Its Clinical Efficacy and Safety and a Psychiatrist's Perspective. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020 Dec 18;14:5559-5574. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- N. M. Bozkurt and G. Unal, “Vortioxetine improved negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia in subchronic MK-801 model in rats,” Behavioural Brain Research, vol. 444, p. 114365, Apr. 202. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Waters et al., “Effects of the selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970 in animal models of psychosis and cognition,” Behavioural Brain Research, vol. 228, no. 1, pp. 211–218, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. E. R. Nickols, S. M. Dursun, and A. M. W. Taylor, “Preclinical evidence for the use of the atypical antipsychotic, brexpiprazole, for opioid use disorder,” Neuropharmacology, vol. 233, p. 109546, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Siwek M, Wojtasik-Bakalarz K, Krupa AJ, Chrobak AA. Brexpiprazole-Pharmacologic Properties and Use in Schizophrenia and Mood Disorders. Brain Sci. 2023 Feb 25;13(3):397. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy W (ed.) ECDEU Assessment Manual for Pychopharmacology. Publication ADM 76–338. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, 235 Education, and Welfare, 1976; 218–222.

- Mottola CA. Measurement strategies: the visual analogue scale. Decubitus. 1993; 6:56–58.

- Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992 Jul 18;305(6846):160-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Margari F, Matarazzo R, Casacchia M, Roncone R, Dieci M, Safran S, Fiori G, Simoni L; EPICA Study Group. Italian validation of MOAS and NOSIE: a useful package for psychiatric assessment and monitoring of aggressive behaviours. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(2):109-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brynte C, Konstenius M, Khemiri L, Bäcker A, Guterstam J, Levin FR, Jayaram-Lindström N, Franck J. The Effect of Methylphenidate on Cognition in Patients with Comorbid Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Amphetamine Use Disorder: An Exploratory Single-Blinded within-Subject Study. Eur Addict Res. 2023 Nov 29:1-13. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardozzi G, Trovini G, Amici E, Kotzalidis GD, Perrini F, Giovanetti V, Di Giovanni A, De Filippis S. Brexpiprazole in patients with schizophrenia with or without substance use disorder: an observational study. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Dec 4;14:1321233. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nickols, J. E. R., Dursun, S. M., & Taylor, A. M. W. (2023). Preclinical evidence for the use of the atypical antipsychotic, brexpiprazole, for opioid use disorder. Neuropharmacology, 233, 109546. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).