Submitted:

16 January 2024

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

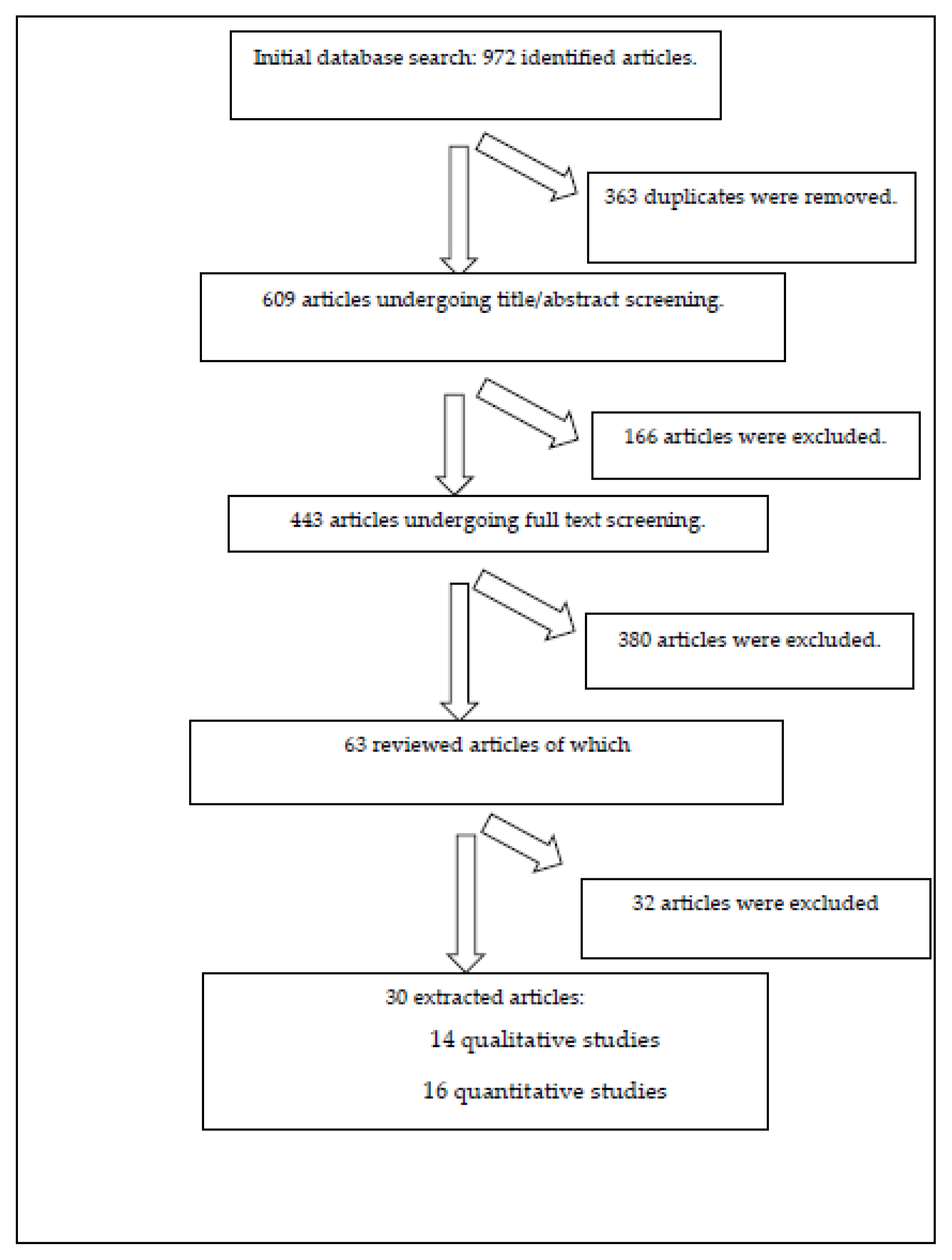

2. Materials and Methods

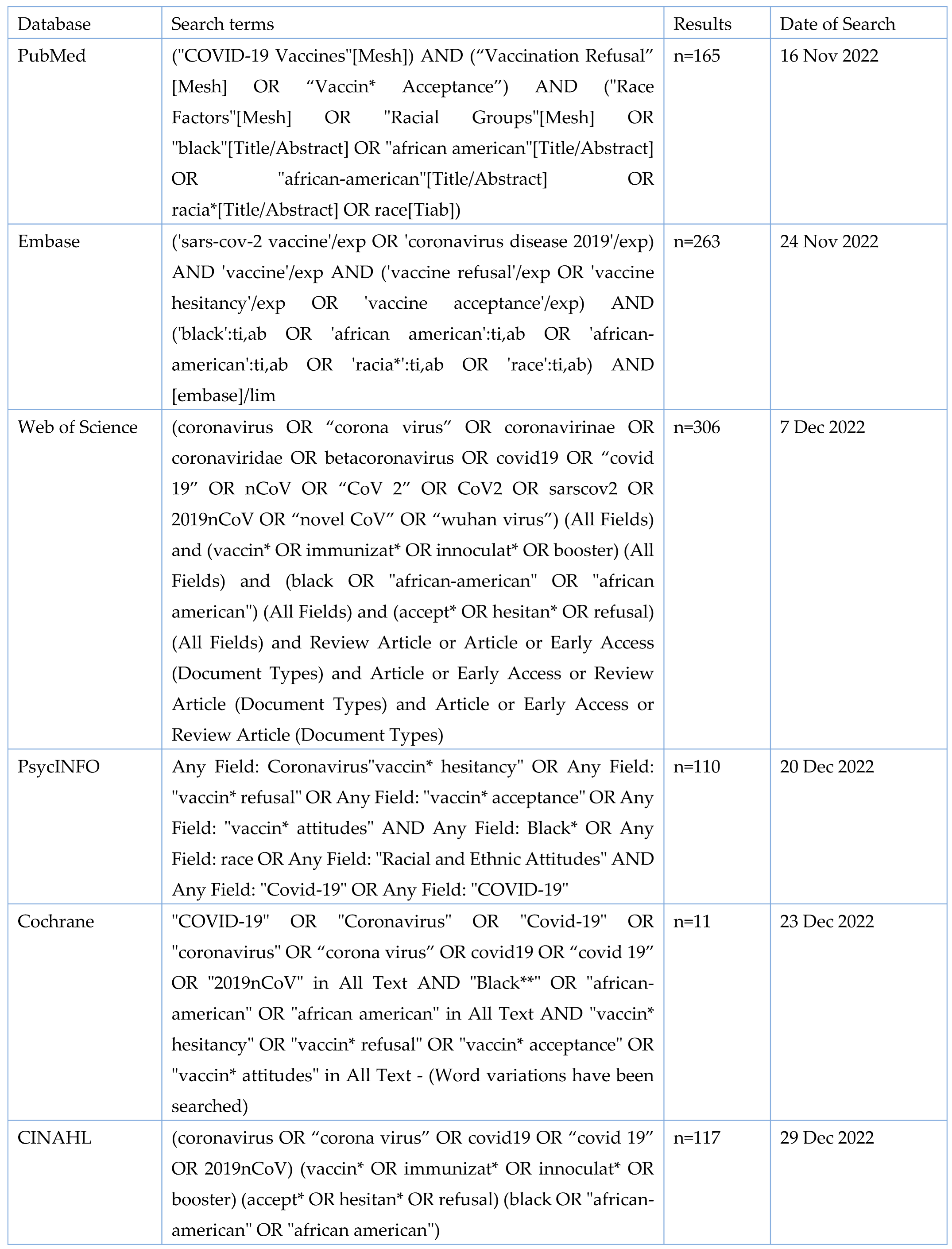

Search Strategy

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Data Extraction

Critical Appraisal

Synthesis procedures

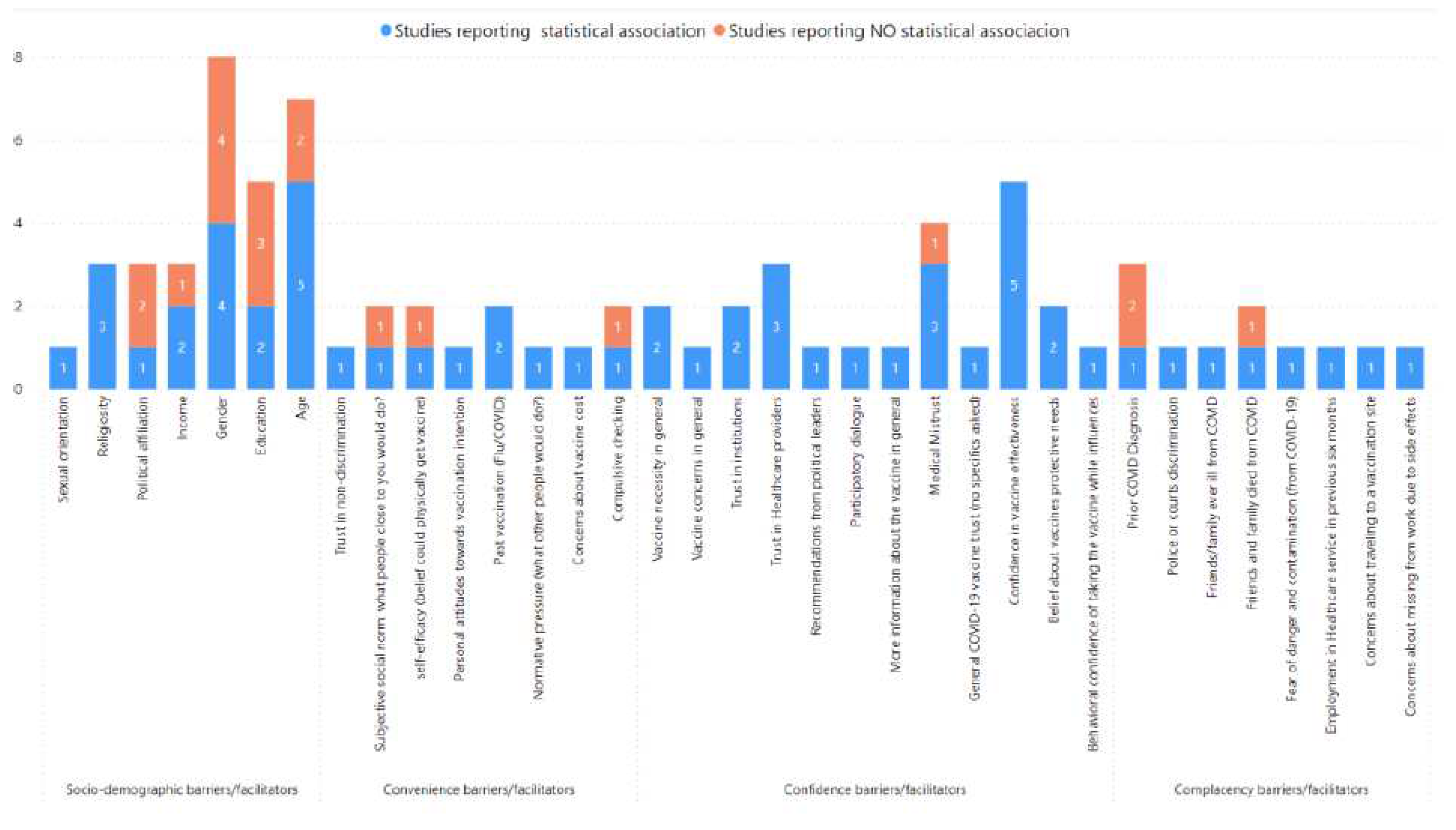

Analysis of the quantitative studies

Analysis of the qualitative studies

3. Results

3.1. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (n=16)

- Characteristics of the studies

3.1.1. Age (n=7)

3.1.2. Gender (n=8)

3.1.3. Education attainment (n=5)

3.1.4. Income (n=3)

3.1.5. Religiosity (n=3)

3.1.6. Political affiliation (n=3)

3.1.7. Confidence/trust in vaccine effectiveness/safety (n=5)

3.1.8. Mistrust/trust in the health system and providers (n=6)

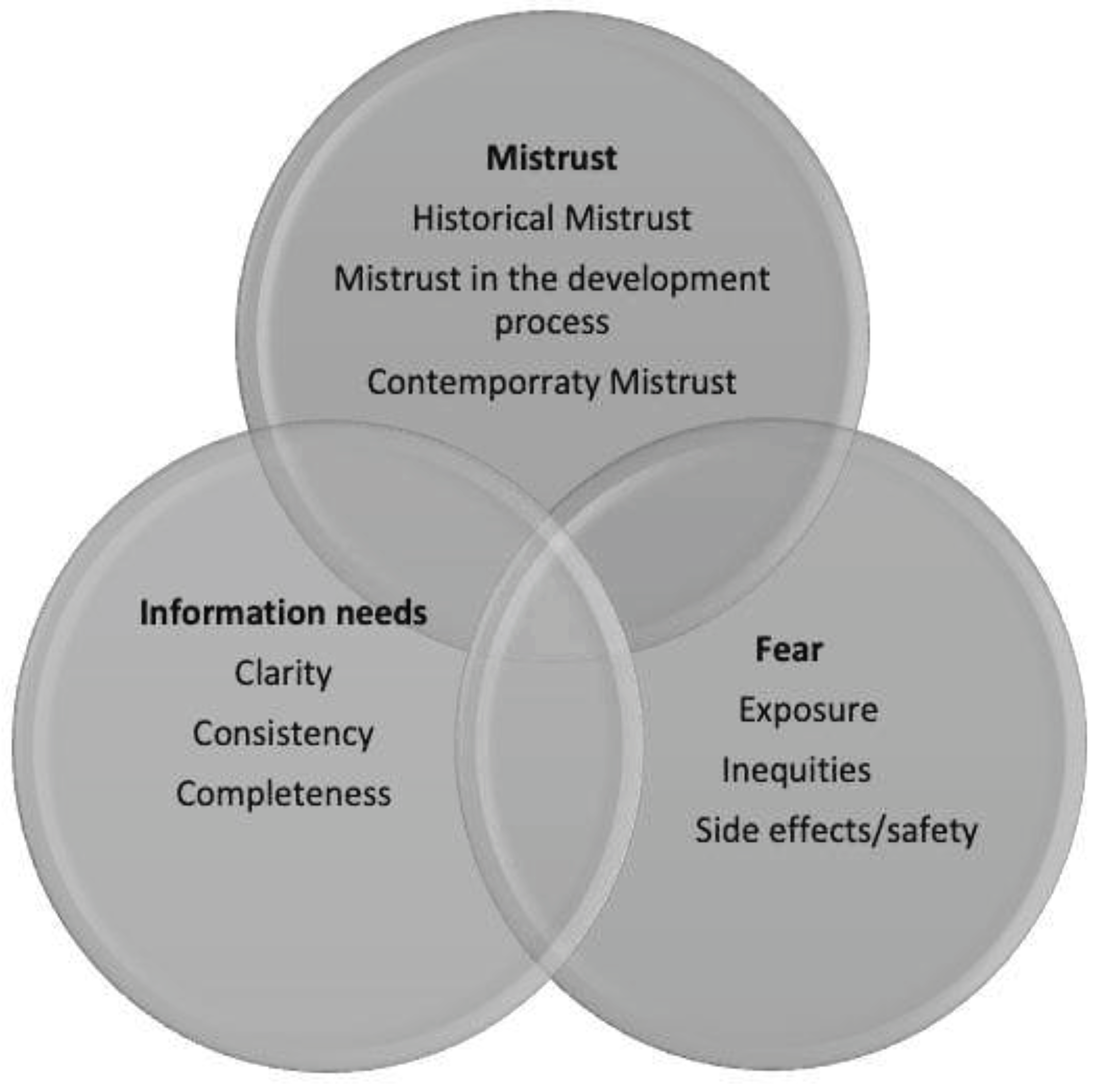

3.2. Qualitative Studies (n=14)

- Characteristics of the studies

- Thematic analysis

3.2.1. Mistrust

- Historical Mistrust

- Mistrust of the vaccine development process

- Contemporary mistrust

3.2.2. Fear of the COVID-19 vaccine

- Fear of unknown side effects and the vaccine being unsafe

- Fear of being exposed to SARS-CoV-2 by the vaccine itself

- Fear of inequitable treatment or of being the object of experimentation

3.2.3. Information needs

3.2.4. Recommended interventions based on the qualitative studies.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Search Terms and Databases

References

- MacDonald, N. E., & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. [CrossRef]

- Allen JD, Abuelezam NN, Rose R, Fontenot HB. Factors associated with the intention to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine among a racially/ethnically diverse sample of women in the USA. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(3). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ten health issues who will tackle this year [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Alshurman BA, Khan AF, Mac C, Majeed M, Butt ZA. What Demographic, Social, and Contextual Factors Influence the Intention to Use COVID-19 Vaccines: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Batelaan, K. ‘It’ s not the science we distrust; it’ s the scientists: Reframing the anti-vaccination movement within Black communities. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hildreth JEK, Alcendor DJ. Targeting COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Minority Populations in the US: Implications for Herd Immunity. Vaccines. 2021;1–12. [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Ramirez CM, Alvarez RM. The politics of vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Soc Sci Q. 2022;103(1):1–120. [CrossRef]

- Marie Reinhart A, Tian Y, Lilly AE. The role of trust in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among Black and White Americans. Vaccine [Internet]. 2022 Nov;40(50):7247–54. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X22013305.

- Ignacio M, Oesterle S, Mercado M, Carver A, Lopez G, Wolfersteig W, et al. Narratives from African American / Black, American Indian / Alaska Native, and Hispanic / Latinx community members in Arizona to enhance COVID - 19 vaccine and vaccination uptake. J Behav Med [Internet]. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dada D, Nguemo J, Sarahann D, Demeke J, Vlahov D, Wilton L, et al. Strategies That Promote Equity in COVID - 19 Vaccine Uptake for Black Communities: a Review. J Urban Heal [Internet]. 2022;15–27. [CrossRef]

- Bogart LM, Dong L, Gandhi P, Klein DJ, Smith TL, Ryan S, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions and Mistrust in a National Sample of Black Americans. J Natl Med Assoc [Internet]. 2022;113(6):599–611. [CrossRef]

- Rabin Y, Kohler RE. COVID-19 Vaccination Messengers, Communication Channels, and Messages Trusted Among Black Communities in the USA: a Review. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities [Internet]. 2023 Nov 10. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40615-023-01858-1.

- Okoro O, Kennedy J, Simmons G, Vosen EC, Allen K, Singer D, et al. Exploring the Scope and Dimensions of Vaccine Hesitancy and Resistance to Enhance COVID-19 Vaccination in Black Communities. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities [Internet]. 2022 Dec 22;9(6):2117–30. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40615-021-01150-0.

- Bagasra AB, Doan S, Allen CT. Racial differences in institutional trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Dec 16;21(1):2104. Available online: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-12195-5.

- Sekimitsu S, Simon J, Lindsley MM, Jones M, Jalloh U, Mabogunje T, et al. Exploring COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Amongst Black Americans: Contributing Factors and Motivators. Am J Heal Promot [Internet]. 2022 Nov 3;36(8):1304–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Qiao S, McKeever BW, Olatosi B, Li X. Listening to Voices from African American Communities in the Southern States about COVID-19 Vaccine Information and Communication: A Qualitative Study. Vaccines [Internet]. 2022 Jun 29;10(7):1046. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/10/7/1046.

- Kricorian K, Turner K. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021;16(8 August):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S:_An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2021, 109, 174–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org.

- Young JM, Solomon MJ. How to critically appraise an article. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2009; 6:82–91. [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Appraisal Tool for cross-sectional studies. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/12/e011458/DC2/embed/inline-supplementary-material-2.pdf?download=true (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Wagner AL, Wileden L, Shanks TR, Goold SD, Morenoff JD, Sheinfeld Gorin SN. Mediators of Racial Differences in COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Uptake: A Cohort Study in Detroit, MI. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;10(1):36. Published 2021 Dec 28. [CrossRef]

- Padamsee TJ, Bond RM, Dixon GN, et al. Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black and White Individuals in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1): e2144470. Published 2022 Jan 4. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham-Erves J, Mayer CS, Han X, et al. Factors influencing intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination among Black and White adults in the southeastern United States, October - December 2020. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):4761-4798. [CrossRef]

- King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260731. Published 2021 Dec 21. [CrossRef]

- Willis DE, Andersen JA, Montgomery BEE, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Experiences of Discrimination Among Black Adults. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(3):1025-1034. [CrossRef]

- Sharma M, Batra K, Batra R. A Theory-Based Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among African Americans in the United States: A Recent Evidence. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(10):1273. Published 2021 Sep 27. [CrossRef]

- Minaya, C., McKay, D., Benton, H., Blanc, J., & Seixas, A. A. (2022). Medical Mistrust, COVID-19 Stress, and Intent to Vaccinate in Racial-Ethnic Minorities. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 12(6), 186. [CrossRef]

- Williamson LD, Tarfa A. Examining the relationships between trust in providers and information, mistrust, and COVID-19 vaccine concerns, necessity, and intentions. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2033. Published 2022 Nov 7. [CrossRef]

- Ogunbajo A, Ojikutu BO. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines among Black immigrants living in the United States. Vaccine X. 2022; 12:100196. [CrossRef]

- McClaran, N. , Rhodes, N., & Yao, S. X. (2022). Trust and Coping Beliefs Contribute to Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Intention. Health communication, 37(12), 1457–1464. [CrossRef]

- Taylor CAL, Sarathchandra D, Kessler M. COVID-19 Vaccination Intake and Intention Among Black and White Residents in Southeast Michigan. J Immigr Minor Health. 2023;25(2):267-273. [CrossRef]

- Thompson HS, Manning M, Mitchell J, et al. Factors Associated With Racial/Ethnic Group-Based Medical Mistrust and Perspectives on COVID-19 Vaccine Trial Participation and Vaccine Uptake in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5): e2111629. Published 2021 May 3. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TC, Gathecha E, Kauffman R, Wright S, Harris CM. Healthcare distrust among hospitalised black patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1161):539-543. [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan D, Mantsios A, Karver TS, et al. Context and Considerations for the Development of Community-Informed Health Communication Messaging to Support Equitable Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines Among Communities of Color in Washington, DC. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(1):395-409. [CrossRef]

- Zhou S, Villalobos JP, Munoz A, Bull S. Ethnic Minorities' Perceptions of COVID-19 Vaccines and Challenges in the Pandemic: A Qualitative Study to Inform COVID-19 Prevention Interventions. Health Commun. 2022 Nov;37(12):1476-1487. [CrossRef]

- Momplaisir F, Haynes N, Nkwihoreze H, Nelson M, Werner RM, Jemmott J. Understanding Drivers of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Blacks. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Nov 16;73(10):1784-1789. [CrossRef]

- Bateman LB, Hall AG, Anderson WA, Cherrington AL, Helova A, Judd S, Kimberly R, Oates GR, Osborne T, Ott C, Ryan M, Strong C, Fouad MN. Exploring COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Stakeholders in African American and Latinx Communities in the Deep South Through the Lens of the Health Belief Model. Am J Health Promot. 2022 Feb;36(2):288-295. [CrossRef]

- Majee W, Anakwe A, Onyeaka K, Harvey IS. The Past Is so Present: Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among African American Adults Using Qualitative Data. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023 Feb;10(1):462-474. [CrossRef]

- Osakwe ZT, Osborne JC, Osakwe N, Stefancic A. Facilitators of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among Black and Hispanic individuals in New York: A qualitative study. Am J Infect Control. 2022 Mar;50(3):268-272. [CrossRef]

- Carson SL, Casillas A, Castellon-Lopez Y, Mansfield LN, Morris D, Barron J, Ntekume E, Landovitz R, Vassar SD, Norris KC, Dubinett SM, Garrison NA, Brown AF. COVID-19 Vaccine Decision-making Factors in Racial and Ethnic Minority Communities in Los Angeles, California. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1;4(9):e2127582. [CrossRef]

- Budhwani H, Maycock T, Murrell W, Simpson T. COVID-19 Vaccine Sentiments Among African American or Black Adolescents in Rural Alabama. J Adolesc Health. 2021 Dec;69(6):1041-1043. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez ME, Rivera-Núñez Z, Crabtree BF, Hill D, Pellerano MB, Devance D, Macenat M, Lima D, Martinez Alcaraz E, Ferrante JM, Barrett ES, Blaser MJ, Panettieri RA Jr, Hudson SV. Black and Latinx Community Perspectives on COVID-19 Mitigation Behaviors, Testing, and Vaccines. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Jul 1;4(7):e2117074. [CrossRef]

- Rios-Fetchko F, Carson M, Gonzalez Ramirez M, Butler JZ, Vargas R, Cabrera A, Gallegos-Castillo A, LeSarre M, Liao M, Woo K, Ellis R, Liu K, Doyle B, Leung L, Grumbach K, Fernandez A. COVID-19 Vaccination Perceptions Among Young Adults of Color in the San Francisco Bay Area. Health Equity. 2022 Nov 10;6(1):836-844. [CrossRef]

- Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Rates across Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups in the United States. Issue brief April 2021. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/265511/vaccination-disparities-brief.pdf.

- Getting the COVID-19 vaccine: Progress and equity questions for the next phase. Brookings. March 4, 2021. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/getting-the-covid-19-vaccine-progress-and-equity-questions-for-the-next-phase/.

- HRSA. Ensuring equity in COVID-19 vaccine distribution. Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/coronavirus/health-center-program.

- Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Moeed A, Naeem U, Asghar MS, Chughtai NU, Yousaf Z, Seboka BT, Ullah I, Lin CY, Pakpour AH. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2021 Nov 23; 9:770985. [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 mortality in adults aged 65 and over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief No. 446 October 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db446.pdf.

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Xu J, Anderson RN. COVID-19 Mortality Update — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023; 72:493–496. [CrossRef]

- Thunström L, Ashworth M, Finnoff D, Newbold SC. Hesitancy toward a COVID-19 vaccine. Ecohealth. (2021) 18:44–60. [CrossRef]

- Viskupič F, Wiltse DL, Meyer BA. Trust in physicians and trust in government predict COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Soc Sci Q. 2022 May;103(3):509-520. [CrossRef]

- Choi Y, Fox AM. Mistrust in public health institutions is a stronger predictor of vaccine hesitancy and uptake than Trust in Trump. Soc Sci Med. 2022 Dec; 314:115440. [CrossRef]

- Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, Paterson P. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018 Jul 3;14(7):1599-1609. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsen EC, Yankey D, Pezzi C, Kriss JL, Lu PJ, Hung MC, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination Coverage, Intentions, Attitudes, and Barriers by Race/Ethnicity, Language of Interview, and Nativity—National Immunization Survey Adult COVID Module, 22 April 2021–29 January 2022. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Oct 3;75(Supplement_2): S182–92. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/75/Supplement_2/S182/6614630.

- Adeagbo M, Olukotun M, Musa S, Alaazi D, Allen U, Renzaho AMN, et al. Improving COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among Black Populations: A Systematic Review of Strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Sep 22;19(19):11971. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/19/11971.

| First author | Study period | Study location | Study population (A.A. and Black Individuals) |

Study outcome | Variables statistically associated with the outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cunningham Erves J, 2021 | October-December 2020 | Southeastern USA | 1,715 | Vaccine willingness | Age Gender Education Religiosity Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Recommendations from political leaders Past vaccination Concerns about vaccine cost |

| Nguyen T, 2021 | November 2020 - March 2021 | Baltimore, Maryland | 140 | Vaccine willingness | Medical mistrust |

| Thompson HS, 2021 | June - December 2020 | Michigan | 394 | Vaccine willingness | Medical mistrust |

| King WC, 2021 | May 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 28,546 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age |

| McClaran N, 2022 | April-September 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 121 | Vaccine willingness | Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Trust in COVID-19 vaccine |

| Bleakley A., 2021 | November-December 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 1,056 | Vaccine willingness | Personal attitudes toward vaccination intention Normative pressure (what other people would do?) Self-efficacy (the belief that one could physically get the vaccine) |

| Ogunbajo A., 2022 | January-February 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 388 | Vaccine hesitancy | Gender Sexual orientation Prior COVID-19 diagnosis Employment in Healthcare service in the previous six months |

| Bogart LM, 2021 | November-December 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 207 | Vaccine willingness | Belief in vaccine necessity Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Subjective social norm (what people close to you would do?) |

| Wagner AL, 2022 | June 2021 | Detroit | 714 | Vaccine hesitancy | Gender Education Income Trust in institutions Trust in healthcare providers Friends or family ever ill from COVID-19 Friends or family ever died of COVID-19 |

| Reinhart AM, 2022 | July 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 1,008 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age Gender Religiosity Political affiliation Trust in institutions Trust in healthcare providers Trust in non-discrimination |

| Willis DE, 2022 | July-August 2021 | Arkansas | 350 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age Belief in police/court discrimination Past vaccination |

| Sharma M, 2021 | July-August 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 428 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age Participatory dialogue Religiosity Behavioural confidence in taking the vaccine while influences |

| Taylor CAL, 2022 | March-April 2021 | Southeast Michigan | 205 | Vaccine hesitancy | Confidence in vaccine effectiveness More information about the vaccine Concern about missing work due to side effects of the vaccine Concerns about travelling to a vaccination site |

| Minaya C, 2022 | December 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 270 | Vaccine willingness | Medical mistrust Fear of danger and contamination from COVID-19 Compulsive checking |

| Williamson LD, 2022 | January 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 210 | Vaccine willingness | Income Belief in vaccine necessity Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine Trust in healthcare providers |

| Padamsee T.J., 2022 | December 2020 - June 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 107 | Vaccine hesitancy | Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Belief in vaccine necessity |

| First author | Study period | Study location | Study population (A.A. and Black Individuals) |

Study outcome | Variables statistically associated with the outcome |

| Cunningham Erves J, 2021 | October-December 2020 | Southeastern U.S. | 1,715 | Vaccine willingness | Age Gender Education Religiosity Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Recommendations from political leaders Past vaccination Concerns about vaccine cost |

| Nguyen T, 2021 | November 2020 - March 2021 | Baltimore, Maryland | 140 | Vaccine willingness | Medical mistrust |

| Thompson HS, 2021 | June - December 2020 | Michigan | 394 | Vaccine willingness | Medical mistrust |

| King WC, 2021 | May 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 28,546 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age |

| McClaran N, 2022 | April-September 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 121 | Vaccine willingness | Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Trust in COVID-19 vaccine |

| Bleakley A., 2021 | November-December 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 1,056 | Vaccine willingness | Personal attitudes toward vaccination intention Normative pressure (what other people would do?) Self-efficacy (the belief that one could physically get the vaccine) |

| Ogunbajo A., 2022 | January-February 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 388 | Vaccine hesitancy | Gender Sexual orientation Prior COVID-19 diagnosis Employment in healthcare service in the previous six months |

| Bogart LM, 2021 | November-December 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 207 | Vaccine willingness | Belief in vaccine necessity Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Subjective social norm (what people close to you would do?) |

| Wagner AL, 2022 | June 2021 | Detroit | 714 | Vaccine hesitancy | Gender Education Income Trust in institutions Trust in healthcare providers Friends or Family ever ill from COVID-19 Friends or family ever died of COVID-19 |

| Reinhart AM, 2022 | July 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 1,008 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age Gender Religiosity Political affiliation Trust in institutions Trust in healthcare providers Trust in non-discrimination |

| Willis DE, 2022 | July-August 2021 | Arkansas | 350 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age Belief in police/court discrimination Past vaccination |

| Sharma M, 2021 | July-August 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 428 | Vaccine hesitancy | Age Participatory dialogue Religiosity Confidence in the vaccine |

| Taylor CAL, 2022 | March-April 2021 | Southeast Michigan | 205 | Vaccine hesitancy | Confidence in vaccine effectiveness More information about the vaccine Concern about missing work due to side effects of the vaccine Concerns about travelling to a vaccination site |

| Minaya C, 2022 | December 2020 | U.S. representative sample | 270 | Vaccine willingness | Medical mistrust Fear of danger and contamination from COVID-19 Compulsive checking |

| Williamson LD, 2022 | January 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 210 | Vaccine willingness | Income Belief in vaccine necessity Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine Trust in healthcare providers |

| Padamsee T.J., 2022 | December 2020 - June 2021 | U.S. representative sample | 107 | Vaccine hesitancy | Confidence in vaccine effectiveness Belief in vaccine necessity |

| Citation | Data collection methods and number of participants | Racial/ethnic composition | Sample | Geographic area | Themes and sub-themes | Results | CASP score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bateman LB. 2022 | 8 focus groups N=67 | 6 AA focus groups + 2 Latinx | 19 years old and older | Alabama and Texas Counties: Jefferson (urban), Mobile County (urban), and Dallas (rural) | Mistrust Fear Information needs | Primary themes driving COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy/acceptance, ordered from most to least discussed, are mistrust, fear, and lack of information. Additionally, they suggest that interventions to decrease vaccine hesitancy should be multi-modal and community-engaged and provide consistent, comprehensive messages delivered by trusted sources. | 8 |

| Budhwani H. 2021 | Interviews N=28 | All AA | Age 15-17 | Alabama (rural areas) | Mistrust Fear Misinformation Elder influence |

Primary themes driving COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy/acceptance were influence of community leaders and elders, fear of side effects and misinformation, and institutional mistrust. Findings suggest that the sentiments and behaviors of older family members and Church leaders may influence AAB adolescents’ vaccine acceptance, particularly in rural communities. |

7 |

| Carson S. 2021 | 13 focus groups N = 70 of which 17 AA |

3 Black/AA focus groups (N=17) 3 Latino (N=15) 3 American Indian (N=17) 2 Filipino (N=11) 2 Pacific Islander (N=10) |

50 Female | California (LA County) | Mistrust Misinformation Concern of accessibility to the vaccine Unclear information |

Primary themes driving vaccine hesitancy/acceptance were misinformation/unclear information, medical mistrust, concern for inequitable access and accessibility barriers. | 8 |

| Ignacio M. 2023 | 34 focus groups N=153 |

10 AA groups 10 Native American 14 Hispanic Participants |

>18 years of age |

Arizona | Mistrust Uncertainty due to disinformation | Primary themes driving vaccine hesitancy/acceptance were mistrust due to historical and contemporary experiences with racism and uncertainty created by disinformation and the speed of vaccine development. Findings across all three racial/ethnic groups strongly suggest an effective way to promote trust in science and increase COVID-19 vaccine confidence is through the use of community-based testimonials or narratives from local leaders, local elected officials, local elders, and other community members who have received the COVID-19 vaccine and who are able to encourage others in their community to do the same. | 9 |

| Jimenez ME. 2021 | 13 focus groups N=111 |

4 AAB (N=34) 3 Latinx (N=24) 4 groups mixed (N=36) 2 healthcare worker groups (N=9) Total Black participants across groups N=68 |

Median age 43 years 87 women (78.4%) ages 18-93 years |

New Jersey counties | Mistrust | Mistrust among Black participants was the main reason for vaccine skepticism. | 8 |

| Kerrigan D. 2023 | 5 focus groups N=36 40 interview participants + crowdsourcing contest N=208 |

2 AA (N=16) 2 Latinx (N=16) 1 African immigrant (N=5). Interviews AA N=19 Latinx N=13 African immigrants N=7 |

19-92 years old | D.C. | Medical mistreatment Mistrust in government Information needs |

Prominent themes among AA participants were mistrust in government and the medical establishment, lack of information, and misinformation. Trusted channels were listed for grassroots mobilization and working with religious leaders. | 9 |

| Majee W. 2023 | 21 individual interviews (16 phone, 5 in person) | 20 AAB interviewees, 1 White | 14.29% (n=3) 30-40yrs, 85.71% (n=18) 60+. Lifestyle coaches, church leaders, and program participants | Central Missouri | Mistrust | Most participants expressed a lack of trust in the government concerning their health and felt unsafe/lacked confidence in government. Continued acts of injustice influence AA’s perceptions of the healthcare system. | 9 |

| Momplaisir F. 2019 | 4 focus groups N=24 | All Black, 1 mixed race | 20-63 years, avg 46 yrs old 17 Non-Hispanic Black, 1 Black Hispanic, 1 mixed race. Black barbershop and salon owners. |

West Philadelphia | Mistrust in government Information needs | The primary reasons for vaccine hesitancy were mistrust in government, hesitancy based on unethical historical practices in research toward the Black community, and skepticism that was not effectively addressed. | 9 |

| Okoro O. 2022 | 8 focus groups N=49 + 30 interviews + surveyed (N=183 of which 120 African American, 40 African, 23 Biracial) one-on-one interviews N=30 |

32 AA, 12 African/Jamaican, 4 Bi/Multiracial in focus groups. All AAB in interviews and survey |

>18 years old, 18-81. 47% male | Minnesota and Wisconsin | Information needs Mistrust | Primary reasons were mistrust in government and misinformation, lack of information, and vaccine literacy. Recommendations included use of community spaces as vaccination sites, engagement of community members as outreach coordinators, and timely provision of information in multiple formats. | 9 |

| Osakwe ZT. 2022 | one-on-one semi structured interviews N=50 | Black individuals (N=34) Hispanic (N=9) and Black/Hispanic (N=3) White/Hispanic (N=4) |

64% women, avg. age 42 44% had high school level education or less. |

New York | Information needs | Primary reasons were influence of social networks, lack of information and communication. This qualitative study found that, among Black and Hispanic participants, receipt of reliable vaccine related information, social networks, seeing people like themselves receive the vaccination, and trusted doctors were key drivers of vaccine acceptance. | 8 |

| Rios-Fetchko F. 2022 | 6 focus groups N=45 1 of the 6 focus groups was of mixed race |

AAB- N=13, Latinx- N=20 AAPI- N=12 | 18-30 years of age | San Francisco Bay Area | Mistrust Information needs |

Primary reasons among all three racial-ethnic groups included mistrust in medical and government institutions, strong conviction about self-agency in health decision-making, and exposure to contradictory information and misinformation in social media. Social benefit and a sense of familial and societal responsibility were often mentioned as reasons to get vaccinated. | 7 |

| Sekimitsu S. 2022 | Individual interviews N=18 |

N=18 Black individuals | 20-79 years old Black, identified as “vaccine hesitant” |

Boston, MA | Mistrust Fear Information needs |

Primary reasons for vaccine hesitancy were lack of trust in the government, healthcare, and pharmaceutical companies, concerns about the rushed development of the vaccine, fear of side effects, history of medical mistreatment, and a perception of low risk of disease. Motivators likely to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake included more data on the vaccine safety, friends and family getting vaccinated (not celebrities), and increased opportunities that come with being vaccinated. |

9 |

| Zhang R. 2022 |

2 Focus Groups N=18 | All AA | 18-30 (N=12), 31-49 (N=4), 50+ (N=2). Participants worked primarily in colleges, churches, and health agencies. 72% female |

3 counties in South Carolina | Information needs Mistrust | Primary reasons were challenges of accessing reliable vaccine information in AA communities primarily included structural barriers, information barriers, and a lack of trust. Community stakeholders recommended recruiting trusted messengers, using social events to reach target populations, and conducting health communication campaigns through open dialogue among stakeholders. Health communication interventions directed at COVID-19 vaccine uptake should be grounded in ongoing community engagement, trust-building activities, and transparent communication about vaccine development. | 8 |

| Zhou S. 2022 | Interviews N=18 | 5 Latinx 8AAs 5 AI/ANs |

21-54 | Denver Metropolitan area | Fear Information needs Mistrust |

Negative perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine were driven by concerns about vaccine safety due to the rapid development process and side effects. AA participants identified seeing others, especially government officials, get the vaccine first as a facilitator for accepting the vaccine, and low trust in the government and healthcare system as barriers to vaccine acceptance. To address the barriers, campaigns should increase credibility of the information and reduce inconsistencies, build trust with communities, and frame messages in a positive manner. |

9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).