1. Introduction

Healthcare systems worldwide are aiming to find new ways to deal with an increasing burden of chronic diseases, increasing healthcare expenditures, and challenges posed by an aging population [

1,

2]. Within the healthcare community, critics argue that the emphasis is too much on biomedical models that primarily focus on diagnosing and treating diseases, with limited attention given to prevention, health promotion, and well-being [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Recognizing this biomedical tendency as rooted in a vision of ‘health as absence from disease’, Huber et al. (2011) introduced a more dynamic concept of health valuing resilience ‘as the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical and emotional challenges’[

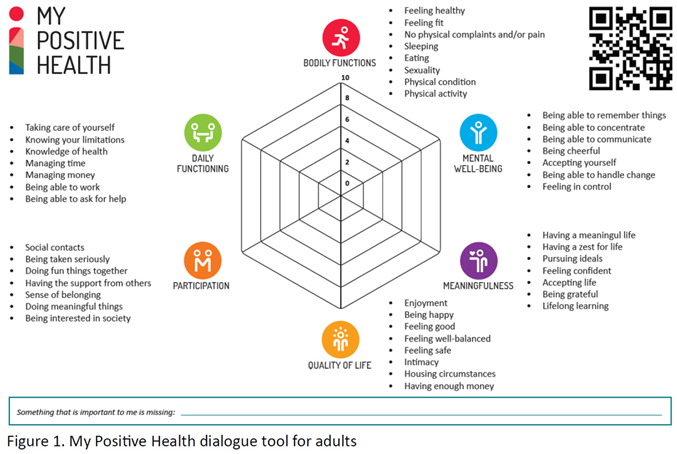

7]. This was deliberately not described as a ‘definition’, which would mean a demarcating criterion, but as a ‘general concept’ intending to be a characterization of a goal to work towards, being enhancement of resilience, overall health and well-being. This concept was further elaborated into Positive Health (PH), which comprises six dimensions: bodily functions, mental wellbeing, meaningfulness, quality of life, participation, and daily functioning [

8]. These dimensions are derived from the responses from patients and citizens on the question what they perceived to constitute health [

8]. Internationally, several conceptualizations of the term positive health have emerged, all sharing a common foundation in the salutogenic approach, positive psychology or lifestyle medicine which rather focus on the resources that promote health than on the mere absence of disease [

9]. Positive Health by Huber et al. (2016), the subject of this review, is written with capitals and referred to as PH in the rest of the article.

For practical use, the method of PH or so-called ‘alternative dialogue’ was developed, which enables people to deal with the physical, emotional and social challenges in life by providing individuals insight in their own health, addressing personal purpose and motivations, and finding directions for change. The first step of this method is to fill out the dialogue tool with average scores of the six dimensions displayed in the Positive Health spiderweb (see Figure 1).

This visually summarizes one's subjective broad health status, which is utilized in consultations with professionals like healthcare providers and social workers, but also in conversations with peers or volunteers. The next step is to identify if there is a wish for change, and if so on which dimension(s). The last step is to identify if and which support the person needs to make this change. Specific versions of the dialogue tool (digitally and on paper) are available for adults, adolescents and children [

10]. Besides, there is a simple version for adults with lower reading skills. These dialogue tools are widely used in the Netherlands, with more than 350.000 unique users (as of June 2023) since their introduction in 2016. In addition, international versions are available in English, German, French, Spanish, Japanese and Icelandic (and more are in development) [

11]. The statements of the adult version are based on the original 32 aspects derived by interviews and a principal component analysis [

8,

12]. For practical use they were later reformulated towards a simpler language level (B1). Although there could be a loss of, discriminating quality, it was considered acceptable since the dialogue tool aims to stimulate self-reflection, and is no measurement tool. Additionally, on request of professionals, a few ‘determinants’ were added, to be able to recognize for example homelessness or debts, leading to 44 statements in total. Recognizing the importance of having a measurement instrument for research purposes alongside the dialogue tool, a dedicated measurement tool was subsequently developed [

13].

PH has been described as a successful transformative innovation [

1,

14]. Integration of the concept (the broad vision on health) and method (spiderweb and alternative dialogue) took place at individual, organizational, community, regional and national levels within the Dutch healthcare system and beyond. PH is considered a promising approach by the Dutch government to address the challenges of promoting well-being and reducing the burden of disease [

15,

16]. Moreover, its impact has transcended national borders, garnering attention and recognition on an international scale [

17]. With the international experiences so far in a variety of countries, the concept and method seem to be universally applicable, with some country- and culture-specific needs. Along with the growing demand for implementation in healthcare practice, questions have arisen concerning its impact, scientifically evaluated effectiveness, and its potential applicability in other settings and domains. At the same time, the need was expressed for a more comprehensive substantiation of the concept and for valid and reliable measurements of its impact [

14,

18]. To more effectively address these urgent questions, this rapid review aims to synthesize the current state of knowledge on PH. It will provide researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and healthcare professionals with a comprehensive overview of the key findings from available studies regarding PH and will identify gaps, needs, and areas for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was based on a rapid review approach following the Cochrane Rapid Review recommendations [

19]. Rapid reviews are a type of review that balance the time-sensitive requirements of policy makers and methodological quality [

20].

The present rapid review was performed according to the following steps:

1. framing of the explorative research question using the SPIDER framework (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) [

21,

22]

2. development of the search strategy,

3. specification of inclusion criteria,

4. abstract screening and study selection,

5. data extraction,

6. synthesis of findings.

The review questions guiding this rapid review are as follows:

What is the current state of knowledge about PH as introduced by Huber et al. (2016) within the available scientific literature? [

8]

Which specific areas regarding the concept and method of PH have been investigated and what are the key findings from these studies?

Which areas and / or topics can we derive from the literature that are important for the implementation of the concept and method of PH at individual, organizational, community, regional, and (inter)national levels?

A comprehensive literature search was performed using electronic databases between April and July 2023. The search strategy was to include all articles citing Huber et al. (2016) within Pubmed, Google Scholar, and CINAHL. The articles in English and Dutch had to be published between 2016 (i.e., the introduction of PH by Huber et al. (2016) and July 2023 (i.e., date of last search).

Studies were included if they met the following predefined eligibility criteria:

Citing PH as conceptualized by Huber et al. (2016) [

8].

PH is part of or related to the research objective and / or study method.

Original research (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods studies, reviews, etc.) in English or Dutch published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

The query ‘cited in’ was used in each electronic database to select all articles that cited Huber et al. (2016). MV and MK independently screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles to exclude all studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e. non peer reviewed records or in other language). Next, full texts of the articles were assessed against the predefined criteria. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through a consensus meeting in which a third reviewer was consulted.

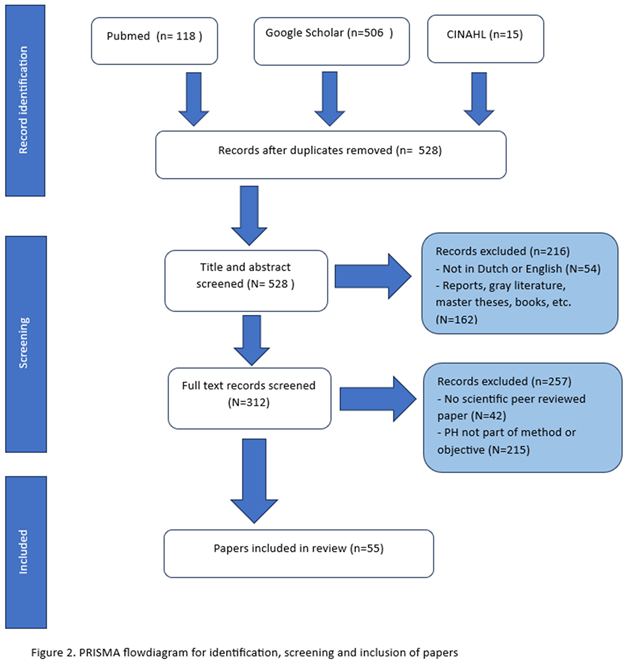

The above search strategy resulted in 639 hits. After removing the duplicates, 528 articles were left for article screening and further review. N = 55 articles were finally included. See Figure 2 for the PRISMA flow diagram.

General information (authors, year, language, study design, study population, and setting) was organized on a data extraction form. The included articles underwent manifest content analysis, which involved a systematic process of categorizing and analyzing content for patterns [

23]. Themes related to the review questions (see above) were identified through an iterative process of inductive coding. MV and MK identified emerging themes and sub-themes and regular meetings with the authors were held to discuss and refine the coding framework. Consensus was reached through discussion and iterative refinement to enhance the reliability and validity of the analysis.

The findings from the analysis are synthesized in a narrative format, which are summarized and discussed below.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

A total of 55 articles were included (see Figure 2). Of those, the majority were written in English (73%) and were published between 2020-2023 (65%). Almost half of the papers concerned qualitative studies (40%), followed by quantitative studies (24%) and mixed-method studies (22%), reflections (9%) and reviews (5%). Most studies were performed in the Netherlands, except from four in European countries and one in South-East Asia. Studies were aiming at different settings: for individual professional use in primary care, hospital care and education and for collective use in communities and in health policy. Some studies focused on professionals’ views on and experiences with the use and feasibility of the Positive Health method in practice. Others focused on various target populations ranging from children to older adults, and from patients with chronic diseases to people with low socioeconomic status. See

Table 1.

3.2. Key themes

In total, five themes were identified: Implementation of PH and its impact, Conceptual development, Development of the PH method, Measurement and monitoring effects, and Scientific application. Each of the themes and their sub themes are discussed below.

3.2.1. Implementation of PH and its impact:

3.2.1.1. Primary care

Within primary care, several projects are described in which PH and its dialogue tool were implemented as a practical method for implementing a holistic approach, with the aim to improve connections between healthcare professionals and their patients and to foster a broad perspective on health during consultation [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Within two of those projects PH was additionally used to serve as a shared framework for enabling organizations to make changes in their organizational and financial structures [

24,

25]. These changes involved piloting a revised reimbursement system at the population level, initiating activities that fostered a positive work environment, and promoting multidisciplinary collaboration. Furthermore, the PH dialogue tool was used in a healthy lifestyle program for obese patients [

28].

A quantitative analysis showed that the implementation of PH within a primary care setting has led to a reduction of 25% of referrals to the hospital as well as related reduction of healthcare costs, improved quality of care, and increased job satisfaction [

24]. Further, in a qualitative case study among primary care physicians it was expressed that embracing the concept and method of PH empowered them to enhance and give substance to their holistic approach to patient care. It provided them with values, while also enabling them to consider the broader context of the patient’s life and desires. Furthermore, the study revealed that the incorporation of PH was related to changes in organizational conditions which enabled primary care physicians to invest more time in their patients and their own well-being. Overall, this led to an increased sense of job satisfaction [

25]. Regarding the lifestyle program for obese patients, positive effects over time were found for physical fitness, BMI, motivation, and (positive) health, with largest effect sizes for changes on the dimensions of PH [

28].

3.2.1.2. Hospital and care

One article described the use of the dialogue tool in two outpatient hospital departments as part of a research project. This qualitative study mentions several advantages as reported by the medical professionals, including enhanced understanding of individual patients’ circumstances and functioning, changed dynamics in resident-patient communication, and heightened awareness of the value of patient-related outcomes and healthcare expenses [

29].

Another article highlighted PH’s application at management level of several hospitals. It was reported that the concept of PH provided guidance for a changed strategic vision towards a more sustainable healthcare framework [

1].

3.2.1.3. Education

In the educational setting, the PH dialogue tool was incorporated into a module aiming to enhance health science and medical students’ understanding of the person behind the patient. The participating students could optionally use the tool to provide structure to their conversations with patients who were dealing with chronic diseases. Students reported that these conversations yielded a more comprehensive understanding of patients’ experiences and made them empathize with them [

30].

3.2.1.3. Communities

Within projects in the community setting, the concept of PH was primarily used as a shared framework to facilitate joint efforts by citizens and local professionals from socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods to initiate health promotion initiatives on each of the dimensions of PH [

31,

32,

33]. Findings of a qualitative analysis showed that the utilization of PH effectively facilitated the attainment of these objectives, catalyzing a continuous trend of transformation within the neighborhood. It enabled the citizens to embrace a new mindset characterized by more positive and adaptive thinking. For local professionals, the concept of PH enabled them to have a broader outlook on health, identifying intrinsic needs, and empowerment of citizens. Additionally, it was described that the local professionals experienced increased awareness of everyone’s unique role in supporting the health of residents and facilitated community collaboration. Overall, the integration of PH seemed to be more effective among local professionals than among citizens [

31].

3.2.1.4. National health and welfare policies

A discourse analysis by the Dutch institute for transitions showed that PH has gained a prominent position in current Dutch healthcare and public health policies, by applying the following development mechanisms for transition: growing, strengthening, replicating, partnering, instrumentalizing, and embedding. Several main reasons for this success are indicated by the authors. Firstly, they suggest that PH offers a unifying language that aligns with government trend of shifting from an illness perspective to a health perspective. Providing a shared framework by its common language is also highlighted as a strength of the concept, enabling it to function as an intermediary between the healthcare and welfare sectors. Further, the co-creation process involving stakeholders during the concept’s development is identified as a contributing factor to its successful incorporation.(14)

3.2.2. Conceptual development

From the included articles several recommendations emerged for further development of PH as a conceptual model. These are summarized below.

3.2.2.1 Construct definition

Some authors remarked that there may be no singular definition of health and emphasize the need to take this into account when further elaborating the concept of PH. According to them, the conceptualization of health depends on contextual factors and scientific perspectives [

9,

34,

35]. Also, it is emphasized that individuals construct their own understanding of health based on personal circumstances and individual characteristics [

9,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. For example, these articles highlight that people from lower socio-economic backgrounds have a more illness-oriented approach to health and focus on different health aspects compared to other groups. To acknowledge viewpoints and interpretations of health, the formulation of the dynamic concept of health is from its inception considered a ‘general concept’ instead of a ‘definition’ – based on sociologist Blumer’s ideas – to indicate the intention for a characterization rather than a demarcating description [

40]. Further, to include various viewpoints on health, the original study was based on a representative sample for the Dutch population [

40,

41]. Regarding content validity, an overlap is noticed by both users and experts across aspects within and between dimensions of the dialogue tool [

29,

42]. For example, the difference between some aspects of the dimensions Mental Wellbeing, Meaningfulness, and Quality of life seems not always clear. This overlap is confirmed by a factor analysis by Van Vliet et al. (2022) [

13]. This study showed that while the six dimensional structure seems appropriate to define the concept, adaptations to the arrangement of aspects of the dialogue tool is needed for further refinement of PH as a construct. It is also mentioned that the current aspects of the dialogue tool comprise both elements that reflect health and elements that influence health, such as housing conditions and financial situation. While these aspects are relevant to facilitate the ‘alternative dialogue’, they may not be suitable to comprise a construct of PH [

42]. Considering the significant influence of the living environment on health, it was recommended to carefully consider incorporating this more explicitly into the concept [

37]. Further, it is advised to make clear how PH relates to other concepts like Quality of Life and Participation [

42].

3.2.2.2. Philosophical and ethical implications

Several philosophical comments are made. First, researchers argue that focusing on PH and its relation to well-being and happiness may significantly expand the boundaries of healthcare and potentially further support medicalization [

14,

43,

44]. Huber underlined that a broad perspective should instead foster collaboration among diverse domains, as opposed to further burdening the medical field [

40]. An implementation study reported that this medicalizing effect was not observed in an experiment with PH within a hospital setting [

29]. Second, several articles argue that resilience and self-management may not be attainable for everyone, as they require a certain level of strength that is not universally present [

37,

38,

43]. Lastly, some concerns are raised about the notion of full accountability for one’s own health, which may mix up health and behavior [

44]. In reply, Huber (2016) refutes this by asserting that the emphasis lies on ability and resilience, which should not be mistaken for behavior or the decision to engage in certain actions or not [

40]. Additionally, it was underscored that competence should be perceived in terms of each individual’s own capacity. Guidance by the ‘alternative dialogue’ should align with this.

3.2.3. Development of the PH method

As more and more professionals started to work with PH, in the included literature several suggestions were made for refinement and elaboration of the method of PH.

3.2.3.1 Applicability and inclusivity

Various versions of the PH dialogue tool are described in the included literature, fitting to specific populations such as children, adolescents, and people with lower reading skills [

13]. Currently, only the development process of the child version has been published in a scientific journal [

45]. Several evaluation studies recommend further elaboration of the PH method to enhance its applicability and effectiveness in various contexts and populations [

25,

29,

31]. First, more clarity regarding the target population and setting is suggested [

29]. In this evaluation study in a hospital, doctors mentioned the broad scope of dimensions that went beyond the scope of some specialized medical professionals. According to them, the dialogue tool was mainly useful for patients with chronic and more complex conditions. Second, concerns are raised that the current versions of the dialogue tool may have the tendency to predominantly reflect a Western, individualistic perspective. Therefore, it is recommended to pay attention to the cultural sensitivity of the PH concept and method when implementing it in non-Western populations [

31]. Likewise, some studies advise to pay attention to aligning the PH method with vulnerable groups – including economically disadvantaged individuals and (frail) elderly – as the literature indicates a lower awareness of how their behaviors can influence their health and a greater emphasis on illness rather than health aspects [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Finally, physicians in a primary care evaluation study noted the prevalence of interpretations of PH among professionals. According to them, this offered the opportunity for customization to align implementation of PH as a shared framework with the preferences of each organization, yet simultaneously introduces ambiguity regarding the optimal approach for its incorporation [

25].

3.2.3.2 Suitability

Perceptions towards the dimensions of PH are investigated in several studies to explore the suitability for implementation of PH in practice [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. A survey study affirms that, as perceived by citizens, the six dimensions of PH better capture health compared to the WHO domains (e.g. physical, mental, and social). Further, it appears that youth health professionals (who work in public health) were generally positive about the concept. However, they indicated that in their daily practice there still seems to be a lack of focus on mental wellbeing and meaningfulness. Time constraints and the availability of numerous alternative conversation methods are reported by them to be barriers for implementation in practice [

48]. A quantitative survey study among mental health care professionals also reports recognition for the importance of all dimensions of PH, except for daily functioning. Patients rated this dimension significantly higher compared to the professionals [

49].

Although Dutch and Belgian nursing students acknowledged the significance of all PH dimensions, they expressed that Quality of Life and Meaningfulness were comparatively less integrated into their curriculum [

46]. On the other hand, paramedic healthcare students regarded participation, mental wellbeing and daily functioning less important compared to patients. Their lecturers rated the aspects of bodily functions and daily functioning as less important compared to patients [

47].

3.2.4. Measuring and monitoring effects of PH

Several articles emphasize that the aspects of the spiderweb are meant to serve as a dialogue tool rather than a measurement instrument [

13,

18,

51]. However, Nahar (2022) observed that along with the growing utilization of PH, the need to measure the impact of working with PH has increased [

18]. To respond to this need, Van Vliet et al. (2021) developed a 17-item measurement instrument through a psychometric study [

13]. Items of this instrument are extracted from the aspects of the dialogue tool. The 17-item PH measurement instrument was confirmed to have adequate psychometric properties in terms of its content and its convergent validity [

51]. In order to obtain more insight in its measurement properties the authors advised further testing of the instrument, e.g. regarding its responsiveness over time. Besides, several fundamental steps for the development of a measurement instrument are advised, such as identification of the target population and refinement of the purpose of measurement [

42]. In general, Nahar (2022) advices that, given the multidimensional, person-specific, context-dependent nature of health, a preferred methodological strategy would involve a mixed-methods approach that combines both quantitative and qualitative analyses [

18].

3.2.5. Scientific application of PH

3.2.5.1 Utilization as a research method

The concept and method of PH appear to be extensively applied as quantitative and qualitative research method across diverse scientific studies. This encompasses evaluations of lifestyle programs (including e-coaching), arts therapy programs, social interventions, and epidemiological studies.

Despite the cautionary note that the dialogue tool is not a validated measurement instrument, ten study projects reported use of the PH aspects to assess baseline characteristics or outcomes in healthcare-related interventions and cross-sectional studies. Among those, five studies utilized (or aimed to use in case of a study protocol) the 42-items (version 1.0) of the dialogue tool to calculate scores per dimension [

32,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Others developed their own measurement system consisting of one question per dimension [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Additionally, one study mentioned the future use of a validated PH measurement instrument once it becomes available [

60]. A study evaluating a holistic lifestyle intervention for obese patients employed the 17-item measurement instrument developed by Van Vliet et al. (2021) found higher positive changes in outcomes by the PH dimensions compared to traditional outcome parameters such as physical fitness and BMI were reported [

13,

28]. On the other hand, no changes on PH dimensions were found over time in a digital coaching program for elderly people in which one question per dimension was used [

58]. At last, in one cross-sectional study among children with a severe chronic and/or congenital skin disorder, relatively high scores on the PH dimensions were found, as an indication for the authors that they were well able to adapt and self-manage [

52].

Furthermore, eight articles report that dimensions of PH were part of their qualitative research methods, either during data collection [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65] or as a framework during data analysis to organize themes based on the various dimensions [

62,

64,

66,

67,

68].

3.2.5.2 Input for development of related health concepts

PH and its dimensions and aspects are utilized as an inspirational source to improve the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) classification system [

69,

70]. Considering the dimensions of PH, a modified classification of the ICF domains has been proposed. Furthermore, the PH aspects have been utilized in validation studies to assess the concurrent validity of a well-being scale [

71] and as a framework for evaluating the face validity of a quality of life measurement scale [

72].

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of key findings

This rapid review shows that since the launch of PH in 2016, numerous scientific articles have emerged discussing the implementation of PH and its impact, its conceptual development, the development of the PH method, measurement and monitoring effects, and scientific application of PH. These articles highlight the transformative potential of PH in shifting from a disease-focused to a health-oriented paradigm of healthcare. Initial evaluation studies reveal positive results both at individual and collective levels. However, a need is expressed by researchers in several articles for further refinement of the conceptualization of PH and ways to make the effects of the PH approach more measurable. Professionals also expressed a desire for a more informed application and elaboration of the PH method across various settings and populations to enhance its effectiveness in practice.

4.2. Reflections

Scientific evaluation of effects is considered by some authors as an important prerequisite for the concept and method PH [

13,

14,

18]. So far, this is mainly available from studies within primary and hospital care, and within communities. In primary care a 25% reduction in hospital referrals and enhanced holistic patient care was observed. Recent follow up research confirms this reduction in referral, resulting also in a drop of total healthcare expenditure [

73]. This approach also improved job satisfaction among primary care physicians. A holistic lifestyle program for obese patients in which the dialogue tool was used, showed positive changes in (positive) health, physical fitness, and BMI.(28) In outpatient hospital departments, PH’s dialogue tool improved communication, patient outcomes awareness, and cost considerations. PH’s application at the management level of hospitals offered an opportunity to a more sustainable healthcare vision. On the community level, PH served as a shared framework for health promotion initiatives in disadvantaged neighborhoods, but the tool’s specific role in achieving these goals requires clarification. On a national level, PH has gained prominence in Dutch healthcare and public health policies [

14,

15]. The language and unifying identity it offers aligns with a shift from disease to health oriented care. Continued research is needed to further explore how and to which extent PH contributes to human health, quality of healthcare and its impact on healthcare systems. For example, a very recent study identified several skills to maintain and improve their PH, with a special focus on people with lower health skills and competences [

74].

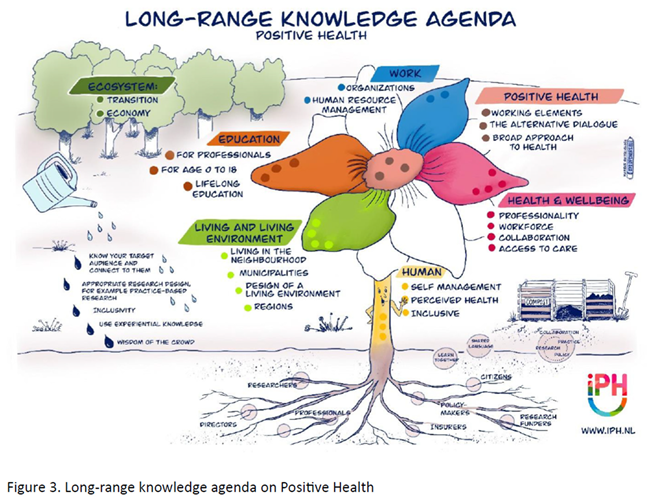

PH regards health as a multi-dimensional construct, involving a wide range of life domains and disciplines. This broad perspective aligns with the current trend in which collaboration across multiple disciplines and sectors to enhance overall health and well-being is stimulated [

15,

75,

76]. It also aligns with the notion that the influence of the living environment on perceived health is undeniably significant [

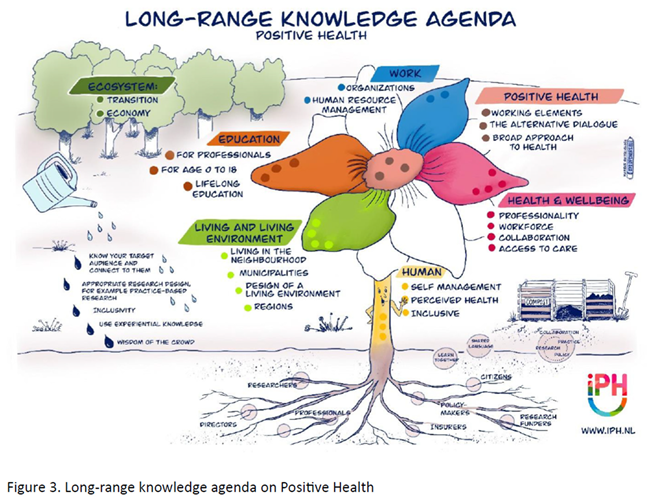

77]. Recently, the institute for Positive Health (iPH) has drafted up a knowledge agenda, aiming to provide direction for research and the development of PH in the upcoming years. Through consultation with citizens, policymakers, researchers, health insurances, and (healthcare) professionals, the knowledge questions were clustered in the following domains: essence of PH, human, living and living environment, learning, working, health- and social care, and the ecosystem (see Figure 3). Being a concept that is originally rooted in healthcare, it is not surprising that this review reveals that studies regarding PH are still mainly performed within this field. However, in line with its multi-dimensional foundation and in line with societal trends, more research on broader domains as stipulated by the PH research agenda is warranted. This can enhance our understanding of effective and ineffective approaches in these various domains, thereby contributing to the knowledge of where and how to implement the PH concept and method.

Initially, due to the substantial interest from healthcare professionals when PH was introduced, the main focus among researchers involved was on empirical testing of PH within healthcare practice before delving deeper in its scientific framework. This enabled pioneering professionals in the field to iteratively refine its method. Results as shown by this review demonstrate that, even though we may not possess a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms, the effects appear promising. However, to enable a sustainable integration of the concept, it is also important to address scientific questions regarding the conceptualization of PH that have been raised. These include suggestions to describe PH as a more demarcated definition with attention for the contextual and situational influence on health, development of a PH construct with corresponding measurement scale, and more focus on the living environment. Regarding the PH method, suggestions are made regarding more clarity regarding suitable settings and groups, extra attention for inclusivity of vulnerable groups, and more specific guidelines for implementation of PH in practice. These proposed questions and suggestions presented in this rapid review can serve as a valuable starting point to collectively consider and prioritize which steps are deemed necessary for the further development and refinement of the PH concept and method. In this regard, an ongoing dialogue between academia and practice may play a pivotal role in facilitating a sustainable implementation of PH across various domains and organizational levels. For instance, through dialogue with both practitioners and researchers, an exploration can be undertaken to assess the feasibility and desirability of refining the PH methodology to suit various settings and populations. This can provide professionals in the field who work with PH with a clear foundation while allowing sufficient room for flexibility, aligning with the specific context of each practice and setting. Also, regarding the wish for clearer definition and demarcation of the concept of PH that appears from some studies, it is essential to collectively determine the extent to which this is desirable, considering PH's foundation as a 'general concept' rather than a rigid definition. From an international perspective, various interpretations of positive health have emerged, all rooted in a salutogenic approach. In this context, researchers are aiming to achieve greater consistency and clarity of the concept [

9]. Research on PH by Huber et al. (2016) can contribute to this movement, for instance, by further delineating guiding principles, particularly focused on aspects such as resilience, meaningfulness, self-care, and patient empowerment. These efforts are vital given the pressing need to address global health challenges and the demands on healthcare systems [

2,

3,

4].

From this rapid review it appears that researchers are using a variety of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches to evaluate PH interventions. Given the person-centered, bottom-up, and complex systems perspective that forms the core of PH interventions it is important to collectively explore scientific approaches that align with these elements. For impact studies, previous recommendations have emphasized the importance of adopting a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods [

18]. Further insights can be used from methodologies such as the Developmental Evaluation approach and action research, which place a stronger emphasis on fostering innovation or change within a complex adaptive system, rather than adhering to a rigid pre-defined evaluation protocol [

78,

79]. The ENCOMPASS framework serves as a good example of such guidance [

80]. Additionally, the principles of 'citizen science' and 'co-creation,' which involve active involvement of the target group throughout the research project, from design to execution to completion, appear to align well [

81]. Furthermore, attention should be paid to inclusivity during research, aiming to make all aspects of the research accessible and understandable for all involved stakeholders [

82]. Finally, in the absence of suitable measurement instruments to assess changes in line with PH, the 17 item measurement instrument is developed to fill this gap[

13,

51]. This instrument is currently the subject of an ongoing project for further testing and optimization to enhance its quality for application in scientific evaluations. The study by Philippens et al. (2021) in which higher positive changes on PH dimensions as measured by the 17 item instrument were found compared to more traditional parameters such as BMI and physical fitness, shows the importance of a broad holistic perspective beyond physical measurements in lifestyle programs [

28]. However, given the widespread use of the PH dialogue tool as a measurement scale in various evaluation studies, it is important to convey a clear message that the dialogue tool itself is not recommended for this purpose.

The findings from this study underscore the necessity of further research, encompassing diverse subjects and employing various study designs. Such endeavors can ultimately contribute to the advancement of health transformation towards more health-oriented care. It is encouraging that ZonMw, the Dutch national funding body for health research and development, has continued to incorporate PH in their research programs and objectives [

83].

4.3. Methodological considerations

A key strength of this study lies in our ability to compile all available scientific research on PH within a relatively short timeframe. However, while we aimed to conduct this process as systematically and meticulously as possible, it is possible that we may have missed scientific studies published in other databases. To ensure the quality of the included research, we chose to exclusively consider studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. This decision led us to exclude other reports and gray literature, which may have limited our insight on developments that were reported directly from policy and practice. Another limitation is that we did not assess the quality of each study individually, and as a result, we cannot make statements about the accuracy of the reported results. Lastly, the initiative for conducting this rapid review originated from researchers at iPH and PHi, who are authors of some included papers as well. To minimize the risk of bias, two researchers from academic institutions have been engaged as co-authors in this study with the task to review both the methodology and (interim) results at various stages throughout the research process.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this rapid review highlights both the potential of PH as a transformative innovation and the challenges for further development of the concept and its method. It underscores the need for continued research, interdisciplinary and international collaboration, and methodological innovation to enable the full potential of PH in improving health, enhancing healthcare quality, and reshaping healthcare systems and society as a whole. By addressing these challenges collectively, we can move closer to these goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: KBD, MK; methodology: KBD, MK and MV; Software: MV and MK; Validation: KBD, MK, MH, MV, SK and TH; Formal analysis: KBD, MK and MV; Data curation: MK and MV; Writing- original draft preparation: MV; writing – review and editing: HPJ, KBD, MK, MH, SK and TH; Supervision: KBD; Project administration: KBD and MV.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Reasonable requests for sharing data can be made by sending an email to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Johansen, F.; Loorbach, D.; Stoopendaal, A. Exploring a transition in Dutch healthcare. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2018, 32, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K., Marengoni, A., Forjaz, M.J., Jureviciene, E., Laatikainen, T., Mammarella, F., et al. Multimorbidity care model: Recommendations from the consensus meeting of the Joint Action on Chronic Diseases and Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Health Policy 2018, 122, 4–11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, M.; Emons, W.H.; Plantinga, A.; Pietersma, S.; Hout, W.B.v.D.; Stiggelbout, A.M.; Marle, M.E.v.D.A.-V. Comprehensively Measuring Health-Related Subjective Well-Being: Dimensionality Analysis for Improved Outcome Assessment in Health Economics. Value Health 2016, 19, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadad, A.R. & O’Grady, L. How should health be defined? BMJ 2008, 337, a2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. The end of disease and the beginning of health. BMJ Opinion, 2008.

- Vanderweele, T.J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Vol. 114, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2017, 8148–56. [CrossRef]

- Huber, M., Knottnerus; et al. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011, 343, 7817, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; van Vliet, M.; Giezenberg, M.; Winkens, B.; Heerkens, Y.; Dagnelie, P.C.; A Knottnerus, J. Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010091–e010091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodryzlova, Y.; Moullec, G. Definitions of positive health: a systematic scoping review. Glob. Health Promot. 2023, 30, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- My Positive Health. Available online: https://vragenlijsten.mijnpositievegezondheid.nl/ (accessed on 05-01-2024).

- Positive Health International. www.positivehealth-international.com/dialogue-tools/ (accessed on 15-01-2024)).

- Huber, M., van Vliet, M., Giezenberg, M., Knottnerus, A. Towards a Conceptual Framework relating to “Health as the ability to adapt and to self manage”. Operationaliering Gezondheidsconcept. 2013:1–163. Available from: http://www.louisbolk.org/downloads/2820.pdf (accessed on 11-12-2024).

- Van Vliet, M.; Doornenbal, B.M.; Boerema, S.; Marle, E.M.v.D.A.-V. Development and psychometric evaluation of a Positive Health measurement scale: a factor analysis study based on a Dutch population. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, F., Loorbach, D., Stoopendaal, A. Positieve Gezondheid: verandering van taal in de gezondheidszorg. Beleid en Maatschappij. 2023, 50, 1:4. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. Landelijke nota gezondheidsbeleid 2020-2024 - Gezondheid breed op de agenda. 2020. Available from: https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-4b47ffb9-76f1-4550-8c07-846124b42818/pdf (accessed on 16-01-2024).

- Zorginstituut Nederland & NZA. Samenwerken aan passende zorg: De toekomst is nu. Diemen; 2020. Available from: https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/werkagenda/publicaties/adviezen/2020/11/27/advies-samenwerken-aan-passende-zorg-de-toekomst-is-nu (accessed on 16-1-2024).

- Huber, M.A.S. , Jung, H.P., Van den Brekel-Dijkstra, K.. Handbook Positive Health in Primary Care: The Dutch Example. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, the Netherlands, 2022.

- Nahar-van Venrooij, L.; Timmers, J. Het meten van een brede benadering van gezondheid vraagt een brede aanpak in wetenschappelijk onderzoek. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidswetenschappen 2022, 100, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.G.; Oliver, S.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Lavis, J.N.; Waddell, K.; Dickson, K. Selecting rapid review methods for complex questions related to health policy and system issues. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., Booth, A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012 Oct, 22, 10, 1435–43. [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cresswell, JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2007.

- Jung, H.P., Jung, T., Liebrand, S., Huber, M., Stupar-Rutenfrans, S., Wensing, M. Meer tijd voor patiënten, minder verwijzingen. Huisarts Wet. 2018, 61, 3, 39–41.

- Lemmen, C.H.C., Yaron, G., Gifford, R., Spreeuwenberg, M.D. Positive Health and the happy professional: a qualitative case study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021 Dec 1, 22, 1.

- Smeets, R.G.M.; Hertroijs, D.F.L.; Kroese, M.E.A.L.; Hameleers, N.; Ruwaard, D.; Elissen, A.M.J. The Patient Centered Assessment Method (PCAM) for Action-Based Biopsychosocial Evaluation of Patient Needs: Validation and Perceived Value of the Dutch Translation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 11785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, R.G.M.; Hertroijs, D.F.L.; Mukumbang, F.C.; Kroese, M.E.A.L.; Ruwaard, D.; Elissen, A.M.J. First Things First: How to Elicit the Initial Program Theory for a Realist Evaluation of Complex Integrated Care Programs. Milbank Q. 2021, 100, 151–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippens, N.; Janssen, E.; Verjans-Janssen, S.; Kremers, S.; Crutzen, R. HealthyLIFE, a Combined Lifestyle Intervention for Overweight and Obese Adults: A Descriptive Case Series Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Bock, L.; Noben, C.Y.G.; Yaron, G.; George, E.L.J.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Essers, B.A.B.; A Van Mook, W.N.K. Positive Health dialogue tool and value-based healthcare: a qualitative exploratory study during residents’ outpatient consultations. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romme, S., Bosveld, M.H., Van Bokhoven, M.A., De Nooijer, J., Van den Besselaar, H., Van Dongen, J.J.J. Patient involvement in interprofessional education: A qualitative study yielding recommendations on incorporating the patient’s perspective. Health Expect. 2020 Aug, 23, 4, 943–57. [CrossRef]

- van Wietmarschen, H.A.; Staps, S.; Meijer, J.; Flinterman, J.F.; Jong, M.C. The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootjans, S.J.M.; Stijnen, M.M.N.; Kroese, M.E.A.L.; Vermeer, A.J.M.; Ruwaard, D.; Jansen, M.W.J. Positive Health beyond boundaries in community care: design of a prospective study on the effects and implementation of an integrated community approach. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoel, Z.E.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Postma, M.J.; Lensink, R.; Koot, J.A.R.; Swe, K.H.; Van Nguyen, M.; Pamungkasari, E.P.; Tenkink, L.; Vervoort, J.P.M.; et al. A Guideline for Contextual Adaptation of Community-Based Health Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Druten, V.P.; Bartels, E.A.; van de Mheen, D.; de Vries, E.; Kerckhoffs, A.P.M.; Venrooij, L.M.W.N.-V. Concepts of health in different contexts: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, B., Verweij, M., Stronks, K. “Gezondheid”: voor iedere context een passend begrip? Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2017, 95, 6, 258–63. 2017, 95, 6, 258–63. [CrossRef]

- Platzer, F.; Steverink, N.; Haan, M.; de Greef, M.; Goedendorp, M. A healthy view? exploring the positive health perceptions of older adults with a lower socioeconomic status using photo-elicitation interviews. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Heal. Well-being 2021, 16, 1959496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broeder, L.D.; Uiters, E.; Hofland, A.; Wagemakers, A.; Schuit, A.J. Local professionals’ perceptions of health assets in a low-SES Dutch neighbourhood: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2017, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronks, K.; Hoeymans, N.; Haverkamp, B.; Hertog, F.R.J.D.; van Bon-Martens, M.J.H.; Galenkamp, H.; Verweij, M.; Oers, H.A.M.v. Do conceptualisations of health differ across social strata? A concept mapping study among lay people. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinterman, F.; Bisscheroux, P.; Dijkema, P.; Hertog, F.D.; de Jong, M.; Vermeer, A.; Vosjan, M. Positieve Gezondheid en gezondheidspercepties van mensen met een lage SES. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen 2019, 97, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.. Antwoord op ‘Gezondheid: een definitie?’’ van Poiesz, Caris en Lapré.’ Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2016, 94, 8, 292–6. [CrossRef]

- Huber, M., van Vliet, M., Boers, I. Heroverweeg uw opvatting van het begrip ‘gezondheid’’.’ Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Geneeskunde. 2016, 160, 1–5. 2016, 160, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C., Terwee, C. Measuring Positive Health; for now, a bridge too far. Public Health. 2019, 170, 70–7. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, E. Kritische vragen bij Positieve Gezondheid. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidszorg en Ethiek. 2017, 3, 81–3.

- Poiesz, T., Caris, J., Lapré, F.. Gezondheid: een definitie? Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2016;94, 7, 252–5. [CrossRef]

- de Jong-Witjes, S., Kars, M.C., van Vliet, M., Huber, M., van der Laan, S.E.I., Gelens, E.N., et al. Development of the My Positive Health dialogue tool for children: a qualitative study on children’s views of health. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2022 Apr, 13,6, 1, e001373. [CrossRef]

- Kablau, K., Van de Velde, I., De Klerk-Jolink, N., Huber, M.A.S. De perceptie van het concept Positieve Gezondheid bij bachelorstudenten verpleegkunde in Nederland en Vlaanderen: een cross-sectionele analyse. Verpleegkunde. 2020, 4, 16–24.

- Karel, Y.H.; Van Vliet, M.; Lugtigheid, C.E.; De Bot, C.M.; Dierx, J. The concept of Positive Health for students/lecturers in the Netherlands. Int. J. Heal. Promot. Educ. 2019, 57, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meerten, E.; Dierx, J.; de Bot, C. Positieve Gezondheid voor jeugdgezondheidszorgprofessionals. JGZ Tijdschr. voor Jeugdgezondheidsz. 2020, 52, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Loo, D.T.M.; Saämena, N.; Janse, P.; van Vliet, M.; Braam, A.W. [The six dimensions of positive health valued by different stakeholders within mental health care]. Tijdschr Psychiatr 2022, 64, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dierx, J.A.J., Kasper, J.D.P. De meerwaarde van positieve gezondheid voor de gepercipieerde gezondheid [Added value of positive health to perceived health]. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2018 Aug, 3, 96, 6, 241–7.

- Doornenbal, B.M.; Vos, R.C.; Van Vliet, M.; Jong, J.C.K.; Marle, M.E.v.D.A. Measuring positive health: Concurrent and factorial validity based on a representative Dutch sample. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2021, 30, E2109–E2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeseneer, H., Van Gysel, D., De Schepper, S., Lincke, C.R., Sibbles, B.J., Versteegh, J.J.W.M., et al. Care for children with severe chronic skin diseases. Eur J Pediatr. 2019 Jul, 178, 7, 1095–103. [CrossRef]

- van Haaps, A.; Wijbers, J.; Schreurs, A.; Mijatovic, V. A better quality of life could be achieved by applying the endometriosis diet: a cross-sectional study in Dutch endometriosis patients. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 46, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Velsen, L.; Broekhuis, M.; Jansen-Kosterink, S.; Akker, H.O.D. Tailoring Persuasive Electronic Health Strategies for Older Adults on the Basis of Personal Motivation: Web-Based Survey Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, M.; Popma, A.; van Amelsvoort, T.; McEnery, C.; Gleeson, J.F.; Ory, F.G.; M. , J.M.W.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Nieman, D.H. ENgage YOung people earlY (ENYOY): a mixed-method study design for a digital transdiagnostic clinical – and peer- moderated treatment platform for youth with beginning mental health complaints in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, I.S.; van Gerven, L.J.; Debeij, S.M.; Bakker, C.H.; Moester, M.J.C.; Mooijaart, S.P.; van der Pas, S.; Vangeel, M.; Gussekloo, J.; Drewes, Y.M.; et al. Positive health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey among community-dwelling older individuals in the Netherlands. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurmuz, M.Z.M.; Jansen-Kosterink, S.M.; Akker, H.O.D.; Hermens, H.J. User Experience and Potential Health Effects of a Conversational Agent-Based Electronic Health Intervention: Protocol for an Observational Cohort Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e16641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurmuz, M.Z.; Jansen-Kosterink, S.M.; Beinema, T.; Fischer, K.; Akker, H.O.D.; Hermens, H.J. Evaluation of a virtual coaching system eHealth intervention: A mixed methods observational cohort study in the Netherlands. Internet Interv. 2022, 27, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierx, J.A.J.; Kasper, H.D.P. The magnitude and importance of perceived health dimensions define effective tailor-made health-promoting interventions per targeted socioeconomic group. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 849013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsner, F.; Matthiessen, L.E.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Marx, W.; O’neil, A.; Welch, A.A.; Hayhoe, R.P.; Higgs, S.; van Vliet, M.; Morphew-Lu, E.; et al. Identifying Future Study Designs for Mental Health and Social Wellbeing Associated with Diets of a Cohort Living in Eco-Regions: Findings from the INSUM Expert Workshop. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm-Faber, T.E.; Engels, Y.; Vissers, K.C.P.; Henssen, D.J.H.A. Views of patients suffering from Failed Back Surgery Syndrome on their health and their ability to adapt to daily life and self-management: A qualitative exploration. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0243329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, L.L.; Blok, M.; van Velsen, L.; Mulder, B.C.; de Vet, E. Supporting eating behaviour of community-dwelling older adults: co-design of an embodied conversational agent. Des. Health 2021, 5, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, B.; de Kock, L.; Liu, Y.; Dedding, C.; Schrijver, J.; Teunissen, T.; van Hartingsveldt, M.; Menderink, J.; Lengams, Y.; Lindenberg, J.; et al. The Value of Active Arts Engagement on Health and Well-Being of Older Adults: A Nation-Wide Participatory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sleeuwen, D.; van de Laar, F.; Geense, W.; Boogaard, M.v.D.; Zegers, M. Health problems among family caregivers of former intensive care unit (ICU) patients: an interview study. BJGP Open 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevo, L.; Kremers, S.; Jansen, M. The Power of Trading: Exploring the Value of a Trading Shop as a Health-Promoting Community Engagement Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Everdingen, C., Peerenboom, B.P., Van Der Velden, K, Delespaul, P.A.E.G. A Comprehensive Assessment to Enable Recovery of the Homeless: The HOP-TR Study. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 661517. [CrossRef]

- van Lonkhuizen, P.J.C., Vegt, N.J.H., Meijer, E., van Duijn, E., de Bot, S.T., Klempíř, J., et al. Study Protocol for the Development of a European eHealth Platform to Improve Quality of Life in Individuals With Huntington’s Disease and Their Partners (HD-eHelp Study): A User-Centered Design Approach. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 719460.

- Huang, M.; van der Borght, C.; Leithaus, M.; Flamaing, J.; Goderis, G. Patients’ perceptions of frequent hospital admissions: a qualitative interview study with older people above 65 years of age. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerkens Y, de Weerd M, Huber M, de Brouwer C, van der Veen S, Perenboom R, et al. Focus op functioneren. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2017 Mar, 5, 95, 3, 116–8. 3, 116–8.

- Heerkens, Y., de Weerd, M., Huber, M., de Brouwer, C., van der Veen, S., Perenboom, R., et al. Reconsideration of the scheme of the international classification of functioning, disability and health: incentives from the Netherlands for a global debate. Disabil Rehabil. 2018, 40, 5, 603–11. [CrossRef]

- Haspels, H.N.; de Vries, M.; Marle, M.E.v.D.A.-V. The assessment of psychometric properties for the subjective wellbeing-5 dimensions (SWB-5D) questionnaire in the general Dutch population. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 32, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrikx, R.J.P., Drewes, H.W., Spreeuwenberg, M.D., Ruwaard, D., Huuksloot, M., Zijderveld, C., et al. Measuring Population Health from a Broader Perspective: Assessing the My Quality of Life Questionnaire. Int J Integr Care. 2019 May, 13, 19, 2, 7.

- Berden, C., Kuyterink, M., Mikkers, M.. Beyond the Clock: Exploring the Causal Relationship between General Practitioner Time Allocation and Hospital Referrals [Internet]. Tilburg (2023). Report No.: 2023–019. Available from: https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/beyond-the-clock-exploring-the-causal-relationship-between-genera (accessed on 15-01-24).

- Sponselee, H.C.S.; ter Beek, L.; Renders, C.M.; Kroeze, W.; Fransen, M.P.; van Asselt, K.M.; Steenhuis, I.H.M. Letting people flourish: defining and suggesting skills for maintaining and improving positive health. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1224470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, F.; Gulis, G.; Karlsson, L.E. Exploration of understanding of integrated care from a public health perspective: A scoping review. J. Public Health Res. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zonneveld, N.; Driessen, N.; Stüssgen, R.A.J.; Minkman, M.M.N. Values of Integrated Care: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laarhoven, K. Human and Planetary Health. The urgency to integrate into One Health. Nijmegen: Radboud University Press; 2023.

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation. Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. The Guilford Pess: New York, USA, 2011.

- Reason, P. , Bradbury, H. The SAGE Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. 2nd ed. Sage: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2001.

- Pinzon, A.L.; Stronks, K.; Dijkstra, C.; Renders, C.; Altenburg, T.; Hertog, K.D.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Verhoeff, A.P.; Waterlander, W. The ENCOMPASS framework: a practical guide for the evaluation of public health programmes in complex adaptive systems. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science Europe. Briefing paper on Citizen Science. 2018. Available online: https://www.scienceeurope.org/our-resources/briefing-paper-on-citizen-science/ (accessed on 15-01-2024).

- Warren-Findlow, J.; Prohaska, T.R.; Freedman, D. Challenges and opportunities in recruiting and retaining underrepresented populations into health promotion research. Gerontol. 2003, 43, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZonMw. https://www.zonmw.nl/en/positive-health (accessed on 15-01-2024).

Table 1.

Overview of included articles.

Table 1.

Overview of included articles.

| Authors |

language |

design |

study population |

Setting* |

| Bock et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

medical specialists |

hospital |

| Bodryzlova et al. (2023) |

English |

review |

n.a. |

research |

| De Maeseneer et al. (2019) |

English |

mixed-methods |

children |

hospital (Belgium) |

| Den Broeder et al. (2017) |

English |

qualitative |

health and welfare professionals |

community |

| Dierx & Kasper (2022) |

English |

quantitative |

citizens |

research |

| Dierx & Kasper (2018) |

Dutch |

quantitative |

citizens |

research |

| Doornenbal et al. (2021) |

English |

quantitative |

citizens |

research |

| Elsner et al. (2022) |

English |

mixed-methods |

citizens |

community (Europe) |

| Flinterman et al. (2019) |

Dutch |

qualitative |

citizens with lower SES |

community |

| Flinterman et al. (2019) |

Dutch |

review |

n.a. |

public health and social work |

| Groot et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

older adults |

community and care |

| Grootjans et al. (2019) |

English |

mixed-methods |

citizens with lower SES |

community |

| Haaps et al. (2023) |

English |

quantitative |

patients |

community |

| Hamm-Faber et al. (2020) |

English |

qualitative |

patients |

hospital |

| Haspels et al. (2023) |

English |

quantitative |

citizens |

research |

| Haverkamp et al. (2017) |

Dutch |

reflection |

citizens with lower SES |

community |

| Heerkens et al. (2017) |

Dutch |

mixed-methods |

n.a. |

healthcare; research |

| Heerkens et al. (2018) |

English |

mixed-methods |

n.a. |

healthcare; research |

| Hendrikx et al. (2019) |

English |

quantitative |

citizens |

research |

| Huang et al. (2020) |

English |

qualitative |

older adults |

hospital (Belgium) |

| Huber et al. (2016) |

Dutch |

mixed-methods |

stakeholders in healthcare |

healthcare professionals |

| Huber (2016) |

Dutch |

reflection |

n.a. |

research |

| Hurmuz et al. (2022) |

English |

mixed-methods |

older adults |

community |

| Hurmuz et al. (2020) |

English |

mixed-methods |

older adults |

community |

| Johansen (2018) |

English |

qualitative |

healthcare organizations |

care and cure |

| Johansen et al. (2023) |

Dutch |

qualitative |

n.a. |

national healthcare system |

| Jung et al. (2018) |

Dutch |

quantitative |

patients |

primary care |

| Kablau, Kiki, et al. (2020) |

Dutch |

qualitative |

bachelor students |

education (Belgium, the Netherlands) |

| Karel et al. (2019) |

English |

quantitative |

bachelor students and lecturers |

education |

| Kingma (2017) |

Dutch |

reflection |

n.a. |

research |

| Kramer et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

older adults |

community |

| Lemmen et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

primary care professionals |

primary care |

| Moens et al. (2022) |

English |

quantitative |

older adults |

community |

| Nahar et al. (2022) |

Dutch |

reflection |

n.a. |

research |

| Platzer et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

older adults with low SES |

community |

| Pardoel et al. (2022) |

English |

qualitative |

citizens |

community (South-East Asia) |

| Poiesz (2016) |

Dutch |

reflection |

n.a. |

research |

| Philippens et al. (2021) |

English |

quantitative |

overweight and obese patients |

primary care |

| Prevo et al. (2020) |

English |

mixed-methods |

low ses community |

community |

| Prinsen & Terwee (2019) |

English |

qualitative |

stakeholders in healthcare |

research |

| Romme et al. (2020) |

English |

qualitative |

healthcare students |

education |

| Smeets et al. (2022) |

English |

qualitative |

patients with chronic conditions |

primary care |

| Smeets et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

patients with chronic conditions |

primary care |

| Stronks et al. (2018) |

English |

qualitative |

citizens |

community |

| Van Doorn et al. (2021) |

English |

mixed-methods |

adolescents with mental problems |

mental health care |

| Van Druten et al. (2022) |

English |

review |

n.a. |

research |

| Van Everdingen et al. (2021) |

English |

mixed-methods |

homeless people |

community |

| Van de Loo et al. (2022) |

Dutch |

quantitative |

mental healthcare professionals |

mental healthcare |

| Van Lonkhuizen et al. (2021) |

English |

qualitative |

patients with Huntington disease |

community |

| Van Meerten et al. (2020) |

Dutch |

mixed-methods |

youth health professionals |

community |

| Van Sleeuwen et al. (2020) |

English |

qualitative |

caregivers of ICU patients |

hospital |

| Van Velsen et al. (2019) |

English |

quantitative |

older adults |

community and care |

| Van Vliet et al. (2021) |

English |

quantitative |

n.a. |

research |

| Van Wietmarschen et al. (2022) |

English |

qualitative |

citizens with lower SES |

community |

| Wittjes et al. (2022) |

English |

qualitative |

children |

hospital and community care |

| N.a.= not applicable; SES = social economic status; * Dutch setting if not specified |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).