1. Introduction

Financial intermediaries are fundamental to the whole financial system and banks have particular stand among them by executing various specific roles. Especially, banks with their one fundamental function of attracting savings and afterwards supplying financing, stimulate economic activity and growth, and consequently shape economic cycles . According to Allen and Carletti (2008) banks alleviate the information asymmetry problems by having extra cost in order to monitor the borrowers. The authors also stated that due to banks’ role of decreasing agency costs in the transactions between lenders and borrowers, banks act as corporate governance mechanism and provide efficient allocation of economic resources through the time. Moreover, by executing the function of interterm poral smoothing, banks diversify the funds and risks which cannot be achieved by individuals themselves (Tirole, 2006).In their paper Diamond (1984), and Ramakrishnan and Thakor (1984) highlighted that diversification creates value by decreasing costs, which would be too costly if had done by individuals. Moreover, banks facilitate access to direct financing for corporates and individuals, which in some occasions could not be achieved in another case. Consequently, by channelling the funds, banks stimulate the economic activity and contribute to the growth in the country.

However, liquidity creation (Allen, 1981) role of banks is considered as central one in contemporary financial intermediation theory and it is referred as qualitative asset transformation by Bhattacharya and Thakor (1993). Liquidity creation role is argued as the most important function of banks by Diamond and Dybvig (1983).The volume of both liquid assets and liabilities of the banking sector not only determines the profitability of the banks, but also serves for overall soundness and sustainability of the whole financial sector. The most recent crises of 2007-2008 is a good example for the highlighting importance of managing adequate liquidity levels.

The theory provides that market contestability in banking sphere directly influences the liquidity1 dynamics of the banks. While there are few empirical studies dedicated exploring the relationship between competition and liquidity creation, theory suggests competition may both improve and worsen the liquidity creation by banks. Obviously competition and liquidity management oriented policies provide direct influence on the financial stability2 of a country, thus empirical analysis of the relationship between banking competition and liquidity creation will present considerations for improvement of the banking policies. The aim of the paper is to empirically analyse whether competition in the US banking sector for the period of 1976-2000 decreases, increases or has no effect on banking liquidity creation. Additionally, the credit crunch period of 1992-1994 is also examined separately, to compare the impact of competition on liquidity creation ability of banks during the crisis period and “normal times”. The conclusions of the paper are expected to contribute to the policy formation to stimulate efficiency in the banking sector.

This paper is organized as follows. Next section presents the review of existing theoretical and empirical literature from three strands. Then since the empirical testing is implemented in the US banks,

Section 3 provides the specific information about the US banking industry in order to be useful for the purposes of the paper.

Section 4 describes the data, and the methodology to be followed for determining the impact of competition on banking liquidity creation and also methods for estimating relative measures.

Section 5 presents the findings of the empirical test and finally the paper is completed with

Section 6 for conclusions and with suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

As theory suggests, while on the one hand competition improves the bank liquidity and solvency, on the other hand it poses problems for the liquidity and solvency. Findings of the study by Carletti and Leonello (2012) showed that competition is beneficial to financial stability by improving liquidity creation ability of banks. The authors build the model with two types of equilibrium; in the no default equilibrium in higher competitive environment banks can withstand the liquidity shocks since they own satisfactory level of liquidity and in the mixed equilibrium where monopolistic environment dominates, risky banks in the good state sell part of their loans and remain solvent, and in the bad state banks sell all of the loan portfolio and default. Boyd and De Nicolo’ (2005) in their paper argue that the evidence found in existing theoretical literature which supports the view that increased competition prompts higher interest rates on loans and fragile bank structure does not truly explain the situation and thus they support the view of risk incentive mechanism that results in an opposite relationship. In other words, authors show that due to risk incentive mechanism, decreased market competition induces higher loan rates and thus more fragile banking structure. Despite this study does not make an explicit statement about the relationship between competition and liquidity supply, but we can infer that decreased competition will influence liquidity supply in a negative way since as a result of lower competition banks will own more fragile structure and this will affect bottom line negatively and will lead a decrease in liquidity creation. Moreover, in a study by Keeley (1990), which also does not explicitly examine competition and liquidity creation relationship, found that in the weak competitive environment, where banks exercise more market power, a bank is subject to lower default risk.

While above suggestions are the ones that root from a theoretical point of view, unequivocally there is a need for an empirical inquiry to analyse an influence of banking competition on liquidity creation by banks. However, there are few empirical papers dedicating analysis to this strand. Joh and Kim (2013) examined the relationship between competition and liquidity creation with panel set of 25 OECD countries from 2000 to 2010. Findings show that as banking industry becomes less competitive, banks provide more to liquidity creation in which large banks play a significant role. The authors found that one standard deviation increase in competition intensity results with reduction of 3.5% in liquidity. Horvath et al (2014) evaluated the impact of bank competition on liquidity creation in Czech banks and sample period was between 2002-2010. The authors applied the dynamic generalized method of moments (GMM) to the panel dataset. Empirical evidence of the study was a finding of a negative effect of competition on liquidity creation. The authors explained the negative effect of competition with the fact that under fierce competition banks become more fragile and consequently, banks decrease their lending and deposit activities. In other words, enhanced competition puts pressure on the bottom line in the income statement and banks become less incentivized towards both to lend due to the risk of loans losses, and to take deposits due to the risk of bank runs. Also in a very recent study, Jiang et al (2016) gave a contribution to this strand by examining US banks from the 1980s to 1990s with gravity model and found the negative influence of competition as in previous empirical studies. The authors showed that there are two channels through which competition puts a negative impact on liquidity creation; the first, higher pressure on profit margins and the second, in increased market contestability banks become less willing to maintain along-term relationship with customers.

Empirical works addressing the construction of relative metrics for liquidity creation by banks are not abundant. The first paper dedicated to creating bank liquidity metrics belongs to Deep and Schaefer (2004). They designed a ratio called liquidity transformation gap3 to measure liquidity creation. Later, more comprehensive liquidity measure was developed by Berger and Bouwman (2009) which addressed the limitations that mentioned above for liquidity transformation gap. Berger and Bouwman (2009) considered the off-balance sheet activities and also with the aim to prevent size bias, small, medium and large banks comprised the sample. The authors preferred to sort the loans according to the category, rather than maturity factor. Another necessary contribution to liquidity measure, in addition to the standard view of liquidity creation, was examining both asset side and liability sides of the balance sheet. Since banks may alter liquidity volume on the right-hand side of the balance sheet, firstly by changing the funding sources of liabilities. Second, in their studies, Diamond and Rajan (2001) and Thakor (1996)showed that bank capital also places an impact on liquidity creation.

Since it is hard to observe and to assess the different degree of competition, unlike liquidity creation measures, there is a vast list of papers dedicated to building various competition measures (Leon, 2014). Literature review shows that competition measures in the banking sector are grouped into structural methods, which derives the intensity of competition from the market structure, and non-structural methods, in which level of competition is determined by the bank behaviour in the market.

Structural measures often used for developing countries. Traditional approach or so-called structural approach, for measuring banking competition is based on only the structure of the market. The one earliest methods of the traditional approach are paradigm of Structure-Conduct-Performance developed by Bain (1956).Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) measure as is obvious from the name analyses the relationship between market structure, conduct and bank performance.

The main deficiency in traditional approach is the elimination of the fact that behaviour of banks may actually form the market structure (Einav & Levin, 2010). As a response to this criticism, non-structural methods or so-called the New Empirical Industrial Organization (NEIO) focused on how the behaviour of the banks forms the market structure in order to assess competition level (Degryse, et al., 2009). To distinguish different types of competition Panzar and Rosse (1987) developed the H-statistic which is determined by the elasticity of interest revenues with respect to input prices as deposit rate, wages and fixed capital, which means this metrics allows to measure changes in the revenues as a response to input prices. The other frequently used indicator of banking competition by measuring the market power, is Lerner Index which in some literature also called as mark-up test4 and formulated by Abba Lerner in 1934. The Lerner Index is measured as the difference between mark-up and marginal costs relative to output price (The World Bank, 2016). The value of Lerner index ranges between zero and one, and the higher the index value, the lower the banking competition. The advantage of the Lerner index is its flexibility that allows estimation of competition at each point of time (Demirguc-Kunt & Peria, 2010).

The tendency in the literature shows that in order to estimate competition level, the non-structural approach is preferred over the traditional approach, since the latter offers different types of metrics and provides more consistent results5.

3. Overview of US Banking Industry and Deregulation

Considering that empirical testing in this work is based merely on U.S. banks, this section encompasses a general overview of the United States banking industry, its unique features and more importantly, regulatory changes happening through period analysed. Historically, the banking regulation in the United States evolved from five strands, which are restrictions on bank entry and geographic expansion, and on pricing, capital requirements, deposit insurance and assuring control over bank products (Kroszner & Strahan, 2014). In this work the focus is given to bank entry and geographic restrictions.

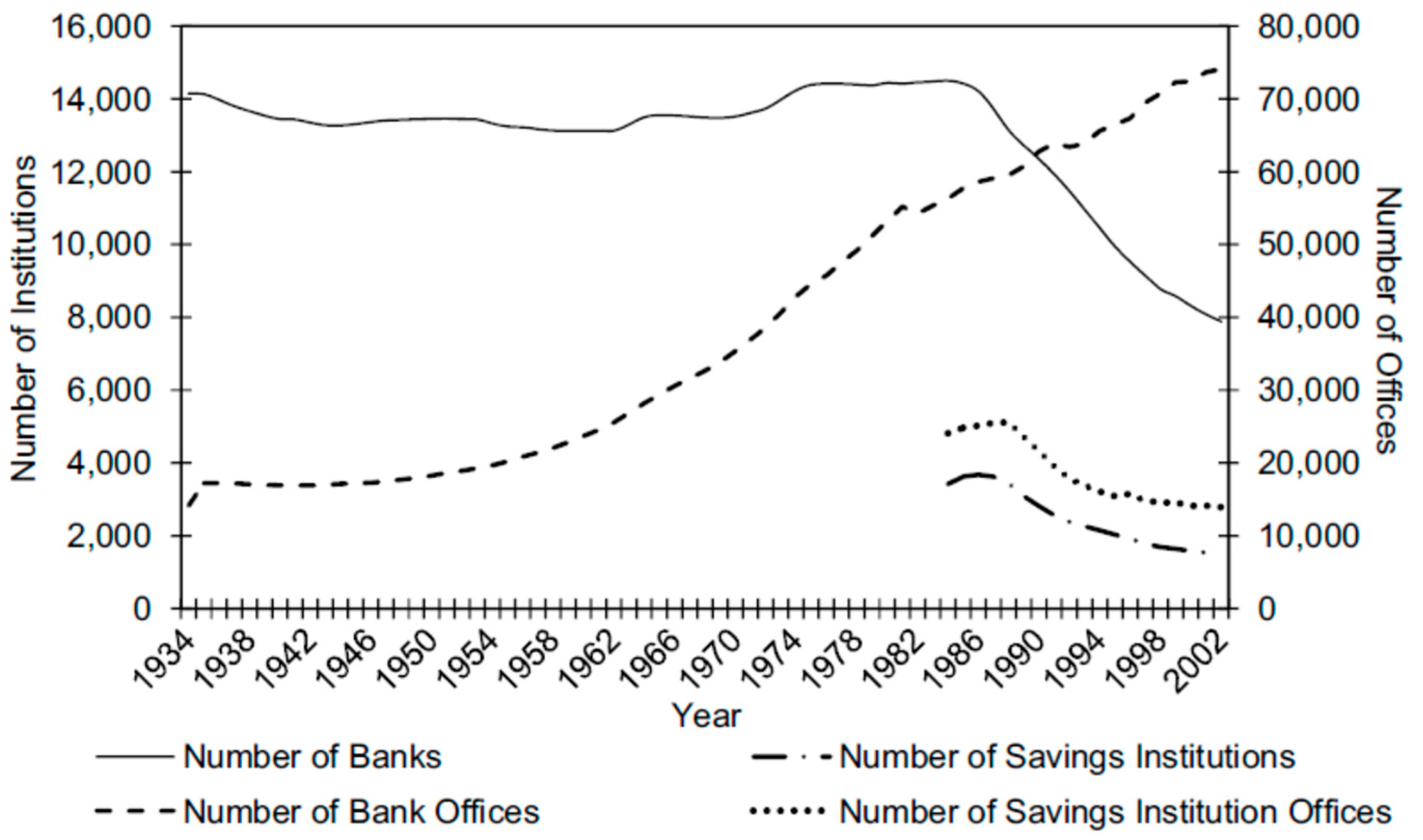

The United States commercial banking enormously differs between periods of 1960s and 1990s by the increase of bank holding companies. Ban of interstate banking and restriction on branching stems from the Act of Bank Holding Company which was in 1956 (Jayaretne & Strahan, 1996).Those limitation sled to such actions of the states, who strived to generate higher revenues, that the states put restriction on banks to operate out of state territory (Kroszner & Strahan, 1999).Starting from 1970s deregulation took place and restrictions on interstate branching were lessened time by time. Forbidden interstate branching was removed through several types of reforms. First, creation of multibank holding companies allowed to possess different banks, but operations of those banks should not be integrated. This consolidation restriction is taken away with second type of reform which allowed branching via merger and acquisitions. Moreover, through the literature review no evidence is found about restricting interstate branching in several states. Another type of reform authorized branching across states and till 1992 almost all states except three were allowed some form of deregulation of branching (Jayaretne & Strahan, 1996). Process of interstate branching legitimately ended with approval of the Riegle-Neal Act in 1994 (Jiang, et al., 2016) and all banks are allowed to enter other states (Kroszner & Strahan, 2014).Following the deregulation, the number of banks in the US decreased by more than fifty percent which occurred mainly due to mergers (see, Appendix Chart A1).Moreover, deregulation did not happen as a result of change in economic conditions, but it did lead to economic changes (Kroszner & Strahan, 2014).Authors, Kroszner and Strahan (1999) in their study showed that branching through merger and acquisition has higher statistical significance and economic impaction growth and efficiency of the sector than other types.

Deregulation resulted in themore efficient banking industry by triggering wheels of more competitive environment. In their study Berger and Mester (2003) show that following the deregulation due to improved cost productivity, inefficiency diminished in the banking sector. Thus, they conclude that deregulation resulted in themore competitive banking industry.Removal of restrictions meant better opportunities for better performing banks or holding companies to exploit and increase their market share (Kroszner & Strahan, 2014). Jayaratne and Strahan (1996) in their paper found that elimination of interstate branching restrictions led operating costs to diminish and consequently charging lower prices on loans.

4. Data and Methodology

To test the impact of banking competition on liquidity creation for theall banks in the US for a period of 1976:Q1-2000:Q4 is chosen in an annual frequency. The needed information for empirical testing is obtained from Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS).

To assess the whether banking competition has positive, negative or no effect on liquidity creation the following methodology will be pursued. To measure the degree of competition the Lerner Index is used among non-traditional metrics. Since the most comprehensive liquidity creation metrics yet developed by Berger and Bouwman (2009), this methodis implemented.

4.1. Methods for Measuring Competition and Liquidity Creation

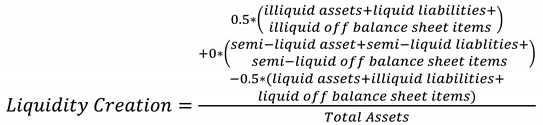

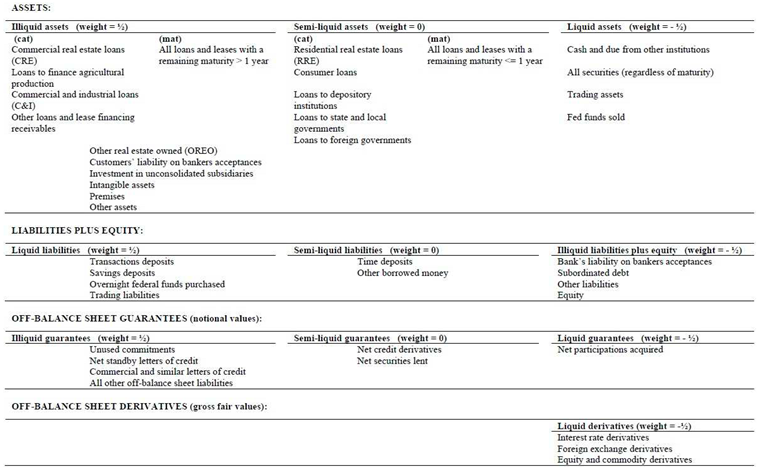

We start with estimating banking competition and liquidity creation measures. To compute the liquidity creation measure, Berger and Bouwman (2009) methodology

6proceeds in the following sequence. Constructing the liquidity creation measure starts with classifying bank activities according to their liquidity

7 by category (and maturity) at both sides of the balance sheet and off-balance sheet activities too. All items on balance and off balance are classified as liquid, semi-liquid and illiquid. While the authors prefer to classify activities based on the category rather than maturity, loan classification is an exception to this. Since Reports of Condition and Income provided by Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council

8 do not present maturity of loans individually, loans categorized considering either category or maturity (Berger & Bouwman, 2009).In the second step, classified activities are assigned with weights of ½, 0 and -½. As theory says, liquidity is created when illiquid assets are transformed into liquid liabilities, thus negative weights are assigned to liquid assets, illiquid liabilities and equity. Since illiquid assets and liquid liabilities are positively weighted, semi-liquid and -liabilities are given zero weight. Finally, to construct liquidity creation measure classified activities are multiplied with respective weights:

Following the methodology by Berger and Bouwman (2009),in order to see through which channels liquidity creation gets affected most, two liquidity creation measures will be calculated; liquidity creation measure including off-balance sheet items and liquidity creation excluding off-balance sheet items. Since there is evidence that banks can contribute to liquidity creation in high amount through off-balance sheet commitments (Berger & Bouwman, 2015), in this work it is also investigated. Moreover, which side of the balance sheet - asset side and liability side -contributes more to the liquidity creation is analysed as well. In this work, liquidity creation measure is built based on categorical differentiation of balance sheet items. Since as noted before instead of differentiating items only according to maturity does not reflect the reality as the information of how an item can be liquidated quickly and with lower cost, which is based on the category of the activity (Berger & Bouwman, 2009).

Next, as one of the frequently implemented metrics, to estimate the degree of competition the Lerner index is calculated following the approach used in Berger, et al. (2008). The formula for the Lerner index is:

–proxy of output of each bank,

, at time

and is estimated as sum of both interest and non-interest revenue divided by total assets, with formula

- marginal cost of each bank

at time

.Firstly the cost of each input prices is found through the translog cost function:

– sum of operational and financial costof each bank at time ;

–total assets of each bank at time ;

– three input prices for deposit rate, labor and fixed capital, with

Deposit rate is found by dividing annual interest expense to total debt; ratio for the wages is calculated by dividing personnel expense to total assets; and finally input price for fixed assets is ratio of sum of capital expenditures and other expenses to total assets. (Degryse, et al., 2009).Since “

the translog cost function should be linearly homogenous in all input prices” (ZARDKOOHI,, et al., 1986), the below shown restrictions should be satisfied:

In empirical literature, it is yet unclear whether homogeneity restriction might influence the inference (ZARDKOOHI,, et al., 1986). While in a study, in which transcendental logarithmic cost function is firstly applied, Benston et al. (1982) found that homogeneity in input prices did not affect the estimates, later in the study by Kolari and Zardkoohi (1986) it was found that it did affect the empirical results in fact.

Then,

is estimated with the formula below:

Finally, the average of the Lerner Indices for each bank over the period is computed to use as an input for the panel regression.

4.2. Panel Data Analysis

In the setting of panel data, there is a high possibility for the regression to suffer from unobserved heterogeneity. Since in most settings of economic data analysis it is more likely to detect correlation of unobserved individual effects with regressors, Fixed Effects Model is implemented.

General Fixed Effect Model is as follows:

If we average the equation,

The fixed effects transformation is obtained by subtracting (6) from (5)

While at this stage it is required to perform ordinary least squares, the existence of possible correlation between

and

, OLS estimation will not provide consistent regression results. The endogeneity may source from omitting important variable(s) and error-in-variables problems. In order to address endogeneity of explanatory variable, the common method known as Instrumental Variable (IV) approach is applied. The role of the instrument is to separate exogenous and endogenous variation in explanatory variable, then to use exogenous part in the regression (Bound, et al., 1995).According to the IV methodology, a new variable,

, is created and considered as exogenous variable and will be used as instrument for the endogenous variable, measure of competition in this setting. However, validity of the instrumental variable is justified when the following two conditions are satisfied:

When orthogonality of the instrument to error terms is violated, which means

,then validity of instrument is demolished.9

However, choice of instrumental variable is not an easy issue and requires fairly well understanding of the relationship between tested variables and variables that are not included in the regression. From practical point of view in the work by Angrist and Krueger (2001), it is emphasized that instrumental variable should be implemented only when the large sample data is tested, since instrumental variables are only consistent but not unbiased, size of the sample is quite crucial. Bound et al. (1995) found that with the use of instrumental variables standard errors become larger. Besides standard error problem, other two plausible problems are also needed to be addressed; first is possible inconsistency as a result of weak correlation between instrument and the error term, and the second, low of regressing endogenous variable on the instrument indicates bias in instrumental variable estimates. Hahn and Hausman (2005) found that biased and inconsistent OLS estimator is preferred over the 2SLS estimator when regression is run with weak instruments. Usage of invalid instruments definitely places impact on the inference.

Besides to assure that instrumental variable is not weak,

in the first stage regression should be significant (Angrist & Krueger, 2001).Objective of ensuring that instrumental variable is not weak is to prevent usage of variable which might have low correlation with original regressor.Relying on more detailed information provided in

Section 3, deregulation through merger and acquisition and act for multibank holding companies are chosen as instrumental variables based on empirical and theoretical proof of positive correlation between deregulation and competition. Besides as noted earlier, Kroszner and Strahan (1999) showed in their study that deregulation through merger and acquisition had the highest impact in banking structure as well as in the economic growth rather than other types of deregulation. To the best of our knowledge, removal of interstate branching restriction and approval for formation multibank holding companies did not aim to control the liquidity level and that is why it is believed that there is alow correlation between liquidity creation and deregulation, which satisfies the second condition of the viable instrumental variable. Deregulation is included into the regression as dummy variables following the methodology by Kroszner and Strahan (1999), where dummy variables take value of 1 starting from the year when restriction of branching is removed and for another dummy variable when multibank holding act is accepted, and takes the value of 0 otherwise (

see Appendix, Table A2).

When there is more than one instrumental variable in the regression to consistently compute the coefficient, two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach is implemented. For an endogenous variable, 2SLS estimator and instrumental variable give same values only if there is one instrument. (Wooldridge, 2010)

Hahn and Hausman (2005) showed that 2SLS estimator has smaller mean squared error and smaller bias than OLS estimate till second order. However, for this fact to hold 2SLS regression should not have lower

.In the first stage, explanatory variable,(

) is regressed on instrumental variable,

and on other variables included in the regression, then fitted values of

is obtained from:

In the second stage, the fitted values for competition,, is obtained from first regression, and then is plugged into the original equation which will provide exogenous estimate of .

Moreover, as control variables bank size and capital asset ratio are used following the work by Jiang et al. (2016), and Horvath et al (2014). Bank size is found as the logarithm of total assets of banks and capital asset ratio is estimated as total equity over total assets. The aim in using the control variables is to analyse how the banks with different size and capital asset ratio differ in the ircontribution to liquidity creation. There is evidence found in literature about the effect of size in liquidity creation; as banks with more assets contribute more to liquidity creation, and banks with less asset contribute in a not significant amount. In terms of capital to asset ratio theory provides opposing views. While some authors claim higher capital amount hinders liquidity creation by banks, the others hold the opposing opinion and suggest that higher capital serves to enhancing liquidity creation of banks (Berger & Bouwman, 2015). To test the existing theories Berger and Bouwman (2009) applied it to US banks for a period of 1976-2000. Empirical evidence showed that for large banks capital affects positively liquidity creation ability, but for small banks the impact is negative. While this fact may differ from one country to another, for the US banks empirical evidence supported both theories depending on the bank size.

Analysis of either positive of negative impact of competition on liquidity creation is broadened with examination of it during the financial crisis period as well, in order to see whether the pattern differs from “normal” times or not. As an event, credit crunch of 1990-1992 in US is chosen to examine for any possible pattern change.

5. Empirical results

This section presents the results for the impact of competition on liquidity creation in the banking sector accounting for the effect of deregulation by implementing the methodology described in previoussection. Besides this whether liquidity creation is generated mainly through the balance items or also through off-balance sheet items is analysed too. Moreover, same methodology is also applied in financial crisis period of 1990-1992, in order to see how influence of competition differs in comparison with “normal times”. The results in this section will enable to make conclusions regarding several pre-mentioned aspects of competition impact on liquidity creation in US banking industry from 1976 to 2000.

Before presenting the results it is very necessary to note about the problems occurred with using very historical data. Since testing period covers 1976-2000, obviously from 70s till 2000 changes with reporting of variables especially changes regarding to their reporting frequency have occurred. Despite there is a documentation available to resolve this problem and to form time series consistently, that piece does not cover the changes regarding off-balance sheet activities. Besides this individual inspection of each account name (the ones used to build liquidity creation measures) showed that there are still cases regarding the reporting frequency which are not covered in those documentation.

To measure influence of competition measure on liquidity creation fixed effect model is employed andall panel regressions are estimated with robust standard errors. It is worth to mention that due to endogeneity of competition measure, Lerner index, fixed effect regression may not address this issue and inferencecan bewrong. Moreover, to remove possible correlation between dependent variable and regressors, independent variables are one year lagged

10.The competition measure is treated as endogenous variable and instrumented with two dummy variables of deregulation. The estimation is done with following equation:

Table 1 displays 2SLS regression results for the above-specified equation. The results are shown in table encompass five regression results; for liquidity creation measure including off-balance sheet items, liquidity creation measure excluding off-balance sheet items and separately for asset side, liability side and off-balance sheet liquidity creation. Coefficient estimates for liquidity creation with off-balance items and off-balance sheet liquidity creation are not statistically significant. For the rest of three regressions, we find significant and negative coefficient estimates for competition measure. This result suggests that as a bank gains more power in the market, or in other words as a bank moves toward a monopoly, liquidity creation ability of a bank decreases. To paraphrase, a decrease in competition poses a negative effect on liquidity supply. Moreover, as competition level decreases, it places diminishing effect more through the asset side, as seen from a comparison of coefficient estimates for asset side and liability side liquidity creation. Coefficient estimates for the variable controlling for the bank size shows that, as the bank has more assets, it contributes more to the liquidity creation. However, for the capital asset ratio the results are rather mixed and while more capital is beneficial for asset side liquidity creation, for the liquidity creation excluding off-balance items and for the liability side liquidity creation more capital has a diminishing effect. A number of observations vary through the regressions due to the issue occurred working with historical data; from the 70s till 2000 reported frequency of variables changed and not all of the changes are documented.

Testing for the impact of competition on liquidity creation during thespecific time period, which is credit crunch of 1990-1992 in the US provides the following results (see Appendix, Table A4). Since deregulation was finished only in 1994, the same methodology is applied and as instruments deregulation of branching through merger and acquisition, and of formation the multibank holding company are utilized for endogenous competition measure. For this period, we find negative and significant coefficient estimates for competition measure which means as more monopolistic becomes the market, the more the negative effect is placed on liquidity creation. When we compare liquidity creation with and without off-balance items, we do not find significant negative impact through the off balance activities on liquidity creation. Another important point is that asset side activities contribute more to liquidity creation rather than liability side and off-balance activities. The size of the bank positively contributes to liquidity creation, where we find statistically significant results only for liquidity creation excluding off-balance sheet items and for the asset side liquidity creation. During crisis period capital ratio results unequivocally demonstrate increasing effect on liquidity creation ability of banks, except for the case with liability side liquidity creation where we do not find statistically significant coefficient estimate.

When we compare crisis period with “normal times”, we do find more negative pressure on liquidity creation excluding off-balance items as a result of a decrease in competitiveness level during the credit crunch. While for both periods impact the direction of the bank size on liquidity creation remains the same and positive, but output for the capital ratioshows rather mixed results and impact direction differs in those periods. Another important issue needed to be mentioned that R2of second stage regression is found to be at very low levels.

Since less competitive environment resulted in a decrease in liquidity creation excluding off-balance activities, then it is tested to see how the situation changes when large banks11 are included as a dummy variable. To examine this, we follow the similar methodology described in a paper by Jiang et al. (2016) and we include anew size dummy variable equal to one when bank size is bigger that median value and zero otherwise. The results are statistically significant except for liquidity creation with off-balance items and off-balance liquidity creation alone and they suggest that in a less competitive environment big banks actually contribute to liquidity creation (see Appendix, Table A5). This finding allows claiming that since in monopolistic environment big banks do contribute to the liquidity creation, since US banking market is less concentrated and market share captured by smaller and medium banks is bigger than of big banks. In other words, in less competitive market liquidity creation is negatively affected and this negative effect is attributed to the small and medium banks.

Empirical testing allows drawing the following conclusions. First, we do find negative and significant coefficient estimates for competition measure, which suggest that during the tested period of 1976-2000, and also during the credit crunch, a decrease in competition level prompts diminishing impact on liquidity creation. Another important finding suggests that liquidity creation is created mainly through the asset side activities and that is why these activities mirror negative effect of decreased competition more than liability side and off-balance sheet side activities. Third, off-balance sheet activities are found to contribute to liquidity supply in a not significant amount during the crisis period., but we cannot make a conclusion for the “normal times” since the results are not statistically significant. Fourth, crisis period intensified the negative impact of decreased competition on liquidity creation ability of banks.

5.1. Instrumental Variable Validity Test

To assure the validity of instrumental variable several specification tests are performed. As noted before for the instrumental variables not to be considered as weak should satisfy the two important conditions; correlation with endogenous variable and zero correlation with the dependent variable. If in the implementation of 2SLS endogenous variable is weakly correlated with its instrument, this leads to wrong inference due to incorrect standard errors and in those cases the ordinary least squares method is preferred over 2SLS. To analyse whether instruments are weak or not, first stage regression statistics is analysed for the reported F-statistics and R

2. To ensure the validity of instrumental variable R

2should not be low and in F-test null hypothesis of instruments are valid should not be rejected. The issue is even if F-test provides the result that variables are valid, it does not guarantee the validity of instruments in essence. Since the validity of instruments is not guaranteed even if performed statistical tests are satisfied, and the results still carry some uncertainty. However, considering the existing empirical evidence between deregulation and competition reviewed in

Section 2, it is assumed that deregulation can be agood instrument for endogenous regressor.

6. Conclusions

As an intermediary financial institution, banks have aparticular role as liquidity providers in the financial market which influences economic activity and growth as well. Examining impact of competition on liquidity creation in thebanking sector is necessary for policy implications. Since through regulation competition level can be controlled, this might resultin changes in liquidity available.

Regarding the effect of competition on banking liquidity creation two opposing views are held. While some authors as Carletti and Leonello (2012)draw a conclusion that increase in the level of competition is beneficial to liquidity creation by enhancing self-discipline. However, these are the findings from the theoretical analysis. Empirical studies in the same orientation are implemented by Joh and Kim (2013) to 25 OECD country banks for a ten years starting from 2000, by Horvath et al. (2014) to Czech Republic banks for a sample period of 2002-2010 and by Jiang et al. (2016) to US banks from 1980s to 1990s. All studies find evidence of the negative influence of increased competition on the ability of banks to create liquidity. The negative impact is explained by the fact that in a more competitive environment banks tend to be less incentivized to lending and taking deposits. Since the increase in competition puts pressure on the bottom line and decreases profitability. Jiang et al. (2016) add another argument for the negative impact that under such conditions banks also become less incentivized to preserve long-term relationships with customers.

The findings of this study do not follow the same line with results of pre-mentioned empirical studies, and negative and significant effect of decreased competition on liquidity creation is found. The study analysed annual data of panel set of US banks from 1976 to 2000. For the 2SLS panel data estimation, competition is measured with the Lerner index and liquidity creation is estimated following the methodology by Berger and Bouwman (2009) and regression is run by employing two instrumental variables of deregulation. The study is extended by analysing the crisis period of 1990-1992 in the US and found the even more negative impact of decreased competition on liquidity creation during the credit crunch. Another major conclusion is that the asset side liquidity creation as the main contributor to overall liquidity creation.Horvath et al. (2014) also find asset side activities contributing more to liquidity creation, while Jiang et al. (2016) find liability side activities as the main contributor. However, through the analysed period off-balance sheet liquidity creation is not found to make animportant difference during the crisis period.

Thus, considering the adverse effect of less competitive environment on liquidity supply, laws and regulation targeting to manage competition level in the banking industry can refer to the results of empirical studies of this orientation and can have apreliminary forecast of what kind of economic consequences it can bring in liquidity supply.

Appendix A

Chart A1.

The number of banks in the US following the deregulation. Source: (Kroszner & Strahan, 2014).

Chart A1.

The number of banks in the US following the deregulation. Source: (Kroszner & Strahan, 2014).

Table A1.

Liquidity creation measure methodology.

Table A1.

Liquidity creation measure methodology.

Table A2.

Date for two types of deregulation which used as dummy variable.

Table A2.

Date for two types of deregulation which used as dummy variable.

| State |

Branching through Merger & Acquisition |

Multibank holding company act |

| AL |

1981 |

1970 |

| AK |

1976 |

1970 |

| AZ |

1976 |

1970 |

| AR |

1994 |

1985 |

| CA |

1976 |

1970 |

| CO |

1991 |

1970 |

| CT |

1980 |

1970 |

| DE |

1976 |

1970 |

| DC |

1976 |

1970 |

| FL |

1988 |

1970 |

| GA |

1983 |

1976 |

| HI |

1986 |

1970 |

| ID |

1976 |

1970 |

| IL |

1988 |

1982 |

| IN |

1989 |

1985 |

| IA |

|

1984 |

| KS |

1987 |

1985 |

| KY |

1990 |

1984 |

| LA |

1988 |

1985 |

| ME |

1975 |

1970 |

| MD |

1976 |

1970 |

| MA |

1984 |

1970 |

| MI |

1987 |

1971 |

| MN |

1993 |

1970 |

| MS |

1986 |

1990 |

| MO |

1990 |

1970 |

| MT |

1990 |

1970 |

| NE |

1985 |

1983 |

| NV |

1976 |

1970 |

| NH |

1987 |

1970 |

| NJ |

1977 |

1970 |

| NM |

1991 |

1970 |

| NY |

1976 |

1976 |

| NC |

1976 |

1970 |

| ND |

1987 |

1970 |

| OH |

1979 |

1970 |

| OK |

1988 |

1983 |

| OR |

1985 |

1970 |

| PA |

1982 |

1982 |

| RI |

1976 |

1970 |

| SC |

1976 |

1970 |

| SD |

1976 |

1970 |

| TN |

1985 |

1970 |

| TX |

1988 |

1970 |

| UT |

1981 |

1970 |

| VT |

1970 |

1970 |

| VA |

1978 |

1970 |

| WA |

1985 |

1981 |

| WV |

1987 |

1982 |

| WI |

1990 |

1970 |

| WY |

1988 |

1970 |

Table A3.

Summary statistics of the variables.

Table A3.

Summary statistics of the variables.

| Variable |

Observation |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

| Liquidity creation |

61801 |

.501 |

5.095 |

| Liquidity creation excluding off-balance items |

110182 |

.384 |

.111 |

| Asset liquidity creation |

241176 |

.063 |

.077 |

| Liability liquidity creation |

110183 |

.327 |

.074 |

| Off-balance liquidity creation |

106547 |

3.425 |

583.757 |

| Competition measure |

171841 |

.107 |

.749 |

| Bank size |

293469 |

.092 |

.366 |

| Capital Asset Ratio (CAR) |

302315 |

10.707 |

1.391 |

Table A4.

Competition impact on liquidity creation in period 1990-1992. The table presents five regression results of instrumented competition measure impact on various liquidity creation measures with two control variables of bank size and capital ratio. The sample covers annual observations during credit crunch period. Two stage least squares is implemented to estimate the regression model. *,**,*** are respectively describes coefficient estimate, robust standard errors, and significance level. (1) and (2) present R2 respectively for the first-stage and second-stage regression.

Table A4.

Competition impact on liquidity creation in period 1990-1992. The table presents five regression results of instrumented competition measure impact on various liquidity creation measures with two control variables of bank size and capital ratio. The sample covers annual observations during credit crunch period. Two stage least squares is implemented to estimate the regression model. *,**,*** are respectively describes coefficient estimate, robust standard errors, and significance level. (1) and (2) present R2 respectively for the first-stage and second-stage regression.

| |

Dependent Variables |

| |

Liquidity Creation |

Liquidity Creation excluding off-balance sheet items |

Asset Liquidity Creation |

Liability Liquidity Creation |

Off-Balance sheet Liquidity Creation |

| Competition measure |

-.192 *

(.092) **

0.037*** |

-.159

(.049)

0.001 |

-.099

(.041)

0.016 |

-.059

(.027)

0.029 |

-.041

(.023)

0.069 |

| Bank Size |

.040

(.043)

0.351

|

.034

(.016)

0.033 |

.026

(.011)

0.019 |

.001

(.007)

0.257 |

.021

(.013)

0.104 |

| Capital Asset Ratio |

1.308

(.088)

0.000

|

0.694

(.263)

0.008 |

.514

(.221)

0.020 |

.181

(.146)

0.217 |

.194

(.048)

0.000 |

| R2 (1) |

0.028 |

0.025 |

0.025 |

0.025 |

0.028 |

| R2 (2) |

0.003 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Number of observations |

22 401 |

36 488 |

36 488 |

36 488 |

22 401 |

Table A5.

Competition impact on liquidity creation in the period 1976-2000 (examining size effect). The table presents five regression results of instrumented competition measure impact on various liquidity creation measures with two control variables of bank size and capital ratio. The sample covers annual observations during credit crunch period. Two stage least squares is implemented to estimate the regression model. *,**,*** are respectively describes coefficient estimate, robust standard errors, and significance level. (1) and (2) present R2 respectively for the first-stage and second-stage regression.

Table A5.

Competition impact on liquidity creation in the period 1976-2000 (examining size effect). The table presents five regression results of instrumented competition measure impact on various liquidity creation measures with two control variables of bank size and capital ratio. The sample covers annual observations during credit crunch period. Two stage least squares is implemented to estimate the regression model. *,**,*** are respectively describes coefficient estimate, robust standard errors, and significance level. (1) and (2) present R2 respectively for the first-stage and second-stage regression.

| |

Dependent Variables |

| |

Liquidity Creation |

Liquidity Creation excluding off-balance sheet items |

Asset Liquidity Creation |

Liability Liquidity Creation |

Off-Balance sheet Liquidity Creation |

| Competition measure |

-.299 *

(.391) **

0.444 *** |

-.012

(.004)

0.004

|

0.000

(.003)

0.972 |

-.021

(.002)

0.000

|

-.121

(.153)

0.430

|

| Capital Asset Ratio |

22.826

(21.709)

0.293

|

-.305

(.028)

0.000

|

-.020

(.014)

0.138

|

-.246

(.026)

0.000

|

12.450

(7.96)

0.118

|

| Size dummy |

.347

(.392)

0.376

|

.008

(.001)

0.000

|

.012

(.001)

0.000

|

.002

(.001)

0.051

|

.197

(.237)

.406

|

| R2 (1) |

0.029 |

0.027 |

0.017 |

0.027 |

0.004 |

| R2 (2) |

0.043 |

0.134 |

0.000 |

0.172 |

0.047 |

| Number of observations |

60 588 |

107 814 |

171 810 |

107 814 |

98 935 |

Notes

| 1 |

“Liquidity is the ability of a bank to fund increases in assets and meet obligations as they come due, without incurring unacceptable losses.” (Bank for International Settlements , 2008). |

| 2 |

“Financial stability – public trust and confidence in financial institutions, markets, infrastructure and the system as a whole – is critical to a healthy, well-functioning economy.” (Bank of England, 2016). |

| 3 |

In their paper, Deep and Schaefer (2004) define liquidity transformation gap as (liquid liabilities-liquid assets)/total assets. |

| 4 |

See (Shaffer, 1994) |

| 5 |

See (Shaffer, 1994) |

| 6 |

Methodology is clearly presented in Appendix, Table A1 |

| 7 |

Liquidity is determined how easy, costless, and time-consuming to transform the on-/off-balance sheet items into liquid ones. (Berger & Bouwman, 2009) |

| 8 |

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) provides financial and structural information for most FDIC-insured institutions in the US. (FFIEC, 2016) |

| 9 |

See (Wooldridge, 2010) and (Hahn & Hausman, 2003) |

| 10 |

Summary statistics of the variables is provided in Appendix, Table A3 |

| 11 |

Defined as over the median values of logarithm of assets |

References

- Allen, F. & Santomero, A., 1998. The theory of financial intermediation. Journal of Banking & Finance, Volume 21, pp. 1461-1485. [CrossRef]

- Allen, B. & Bouwman, C., 2009. Bank Liquidity Creation. Review of Financial Studies 22, p. 3779–3837.

- Allen, F. & Carletti, E., 2008. The Roles of Banks in Financial Systems. In: Oxford Handbook of Banking. s.l.:s.n., pp. 28-42.

- Allen, W., 1981. Intermediation and Pure Liquidity Creation in Banking Systems. BIS Working Papers No-5, February.

- Almarzoqi, R., Naceur, S. B. & Scopelliti, A., 2015. How Does Bank Competition Affect Solvency, Liquidity and Credit Risk? Evidence from the MENA Countries. IMF Working Paper, September, pp. 2-29. [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. & Cetorelli, N., 2003. The Effects of Regulatory Reform on Competition in the Banking Industry. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Volume 35, pp. 663-684. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D. & Krueger, A. B., 2001. Instrumental Variables and Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), pp. 69-85. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D. & Krueger, A. B., 2001. Instrumental Variables and the Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), pp. 69-85. [CrossRef]

- Anzoategui, D., Martínez Pería, M. S. & Melecky, M., 2010. Banking Sector Competition in Russia. The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5449, October, pp. 1-36.

- Bank for International Settlements, 2008. Principles for Sound Liquidty Risk Management and Supervision. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, September, pp. 1-44.

- Bank of England, 2016. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/. [Online] Available at: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financialstability/Pages/default.aspx#.

- Berger, A. & Bouwman, C., 2015. Bank Liquidity Creation and Financial Crises. USA: Nikki Levy.

- Berger, A. & Bouwman, C., 2015. How Much Liquidity Do Banks Create During Normal Times and Financial Crises ?. In: J. S. Bentley, ed. Bank Liquidity Creation and Financial Crises. USA: Academic Press, pp. 105-116.

- Berger, A. & Bouwman, C., 2015. The Links Between Bank Liquidity Creation and Future Financial Crises. In: J. S. Bentley, ed. Bank Liquidity Creation and Financial Crises. USA: Academic Press, pp. 117-121.

- Berger, A., Klapper, L. & Turk-Ariss, R., 2008. Bank Competition and Financial Stability. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4696.

- Berger, A. N. & Bouwman, C. H. S., 2009. Bank LIquidity Creation. Review of Financial Studies, Volume 22, pp. 3779-3837.

- Berger, A. N. & Mester, L. J., 2003. Explaining the Dramatic Changes in Performance of U.S. Banks: Technological Change, Deregulation, and Dynamic Changes in Competition. Journal of Financial Intermediation,, Volume 12, pp. 57-95. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. & Thakor, A. V., 1993. Contemporary Banking Theory. Journal of Financial Intermediation, Volume 3, pp. 2-50. [CrossRef]

- Boone, J. , 2008. A new way to measure competition. The Economic Journal, Volume 118, pp. 1245-1261. [CrossRef]

- Bound, J. , Jaeger, D. A. & Baker, R. M., 1995. Problems with Instrumental Variables Estimation When the Correlation Between the Instrument and the Endogenous Explanatory Variable Is Weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), pp. 443-450. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. & De Nicolo', 2005. The Theory of Bank Risk Taking Revisited. Journal of Finance, Volume 60, pp. 1329-1343.

- Carletti, E. & Leonello, A., 2012. Credit Market Competition and Liquidity Crises. EUI Working Papers. [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S. , 2009. Competition in the Financial Sector: Overview of Competition Policies. IMF Working Paper, March, pp. 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S. & Laeven, L., 2003. What Drives Bank Competition: Some International Evidence. The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3113, August, pp. 1-40.

- Deep, A. & Schaefer, G., 2004. Are Banks Liquidity Transformers?. Harvard University Working Papers Series.

- Degryse, H. , Kim, M. & Ongena, S., 2009. The Industrial Organization Approach to Banking. In: Microeconomics oo Banking: Methods, Applications and Results. s.l.:s.n., pp. 27-56.

- Demirguc-Kunt, A. & Peria, M. S. M., 2010. A Framework for Analyzing Competition in the Banking Sector: An Application to the Case of Jordan. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5499, 1 December, pp. 1-24.

- Demsetz, H. , 1973. Industry structure, market rivalry and public policy. Journal of Law and Economics, Volume 16, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. & Rajan, R., 2001. Banks and Liquidity. The American Economic Review, 91(2), pp. 422-425. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W. & Dybvig, P. H., 1983. Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity. The Journal of Political Economy, 91(3), pp. 401-419. [CrossRef]

- Einav, L. & Levin, J., 2010. Empirical Industrial Organization: A Progress Report. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(2), pp. 145-162. [CrossRef]

- FFIEC, 2016. https://cdr.ffiec.gov. [Online] Available at: https://cdr.ffiec.gov/public/.

- Hahn, J. & Hausman, J., 2003. Weak Instruments: Diagnosis and Cures in Empirical Econometrics. RECENT ADVANCES IN ECONOMETRIC METHODOLOGY, 93(2), pp. 118-125. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J. & Hausman, J., 2005. Estimation with Valid and Invalid Instruments. Annales d’économie et de statistique, Volume 79/80, pp. 24-58.

- Horvath, R. , Seidler, J. & Weil,. L., 2014. How bank competition influences liquidity creation. Economic Modelling, Volume 52, pp. 155-161. [CrossRef]

- Jayaretne, J. & Strahan, P. E., 1996. Entry Restrictions, INdustry Evolution and Dynamic Efficiency: Evidence from Commercial Banking. Federal Reseve Bank of New York Research Paper No. 9630, August, pp. 1-42.

- Jiang, L. , Levine, R. & Lin, C., 2016. Competition and Bank Liquidity Creation, s.l.: SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Joh, S. W. & Kim, J., 2013. Does Competition Affect the Role of Banks as Liquidity Providers?. [Online] Available at: http://www.apjfs.org/conference/2012/cafmFile/5-2.pdf.

- Keeley, M. C. , 1990. Deposit Insurance, Risk and Market Power in Banking. American Economic Review, Volume 80, pp. 1183-1200.

- Kroszner, R. S. & Strahan, P. E., 1999. WHAT DRIVES DEREGULATION? ECONOMICS AND POLITICS OF THE RELAXATION OF BANK BRANCHING RESTRICTIONS. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume November, pp. 1437-1467. [CrossRef]

- Kroszner, R. S. & Strahan, P. E., 2014. Regulation and Deregulation of the U.S. Banking Industry: Causes, Consequences, and Implications for the Future. In: N. L. Rose, ed. Economic Regulation and Its Reform: What Have We Learned ?. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 485-543.

- Leon, F. , 2014. Measuring competition in banking : A critical review of methods. Serie Etudes et documents du CERDI, June, pp. 4-44.

- Mason, J. E. , 1997. Theory of Change in Commercial Banking. In: S. Bruchey, ed. The Transformation of Commercial Banking in the United States, 1956-1991. New York: Routledge, pp. 7-22.

- Neurberger, D. , 1998. Industrial Organization of Banking: A review. INternational Journal of the Economics of Business, 5(1), pp. 97-118. [CrossRef]

- Panzar, J. & Rosse, J., 1987. Testing for "Monopoly" Equilbrium. The Journal of Industrial Economics, Volume XXXV, pp. 443-456. [CrossRef]

- Peltzman, S. , 1977. The gains and losses from industrial concentration. Journal of Law, Volume 20, pp. 229-263. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, S. , 1994. Bank Competition in Concentrated Markets. Business Review Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, March/April, pp. 1-14.

- Strahan, P. E. , 2002. The Real Effects of U.S. Banking Deregulation. Working Paper Series Wharton Financial Institutions Center, September, pp. 2-39.

- Thakor, A. , 1996. Capital Requirements, Monetary Policy, and Aggregate Bank Lending: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Finance, 51(1), pp. 279-324. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank, 2016. http://www.worldbank.org/. [Online] Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/gfdr/background/banking-competition.

- Tirole, J. , 2006. Consumer Liquidity Demand. In: The Theory of Corporate Finance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 447-466.

- Wooldridge, J. M. , 2010. Instrumental Variables Estimation of Single-Equation Linear Models. In: Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 89-112.

- ZARDKOOHI,, A., RANGAN, N. & KOLARI, J., 1986. Homogeneity Restrictions on the Translog Cost Model: A Note. THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE, XLI(5), pp. 1153-1154.

- Zardkoohi, A. & Fraser, D. R., 1998. Geographical Deregulation and Competition in US Banking Markets. The Financial Review, Volume 33, pp. 85-98. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Competition impact on liquidity creation in period 1976-2000. The table presents five regression results of instrumented competition measure impact on various liquidity creation measures with two control variables of bank size and capital ratio. The sample covers annual observations during credit crunch period. Two stage least squares is implemented to estimate the regression model. *,**,*** are respectively describes coefficient estimate, robust standard errors, and significance level. (1) and (2) present R2 respectively for the first-stage and second-stage regression.

Table 1.

Competition impact on liquidity creation in period 1976-2000. The table presents five regression results of instrumented competition measure impact on various liquidity creation measures with two control variables of bank size and capital ratio. The sample covers annual observations during credit crunch period. Two stage least squares is implemented to estimate the regression model. *,**,*** are respectively describes coefficient estimate, robust standard errors, and significance level. (1) and (2) present R2 respectively for the first-stage and second-stage regression.

| |

Dependent Variables |

| |

Liquidity Creation |

Liquidity Creation excluding off-balance sheet items |

Asset Liquidity Creation |

Liability Liquidity Creation |

Off-Balance sheet Liquidity Creation |

| Competition measure |

-.586 *

(.653) **

0.370*** |

-.029

(.039)

0.000

|

-.023

(.003)

0.000 |

-.021

(.002)

0.000 |

-.220

(.281)

0.435 |

| Bank Size |

.415

(.319)

0.319

|

.017

(.005)

0.000 |

.017

(.000)

0.000 |

.001

(.001)

0.668 |

.149

(.151)

0.323 |

| Capital Asset Ratio |

25.053

(.414)

0.292

|

-.189

(.039)

0.000 |

.097

(.019)

0.000 |

-.245

(.026)

0.000 |

12.988

(8.326)

0.119 |

| R2 (1) |

0.038 |

0.029 |

0.037 |

0.029 |

0.025 |

| R2 (2) |

0.034 |

0.033 |

0.010 |

0.169 |

0.043 |

| Number of observations |

60 588 |

107 814 |

171 810 |

107 814 |

98 935 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).