1. Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is the preferred reperfusion therapy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Despite an effective coronary flow restoration in a timely fashion, some categories of patients are still at increased risk of death. As a general principle, traditional cardiovascular risk factors are also associated with higher in-hospital or long-term mortality after STEMI. In this context, some evidence [

1,

2,

3] suggests that smoking habit can be associated with a lower unadjusted risk of all-cause mortality at 1 year as well as a lower rate of death or hospitalization for heart failure (HF) after STEMI lower. This phenomenon – also known as the smoker’s paradox – remains controversial as its evidence are still conflicting. More importantly, no clear pathophysiological mechanism would sustain potential protection conferred by a smoking habit to STEMI patients. The purpose of this study was to assess whether smoking could be associated with mortality in patients with STEMI referred to pPCI in one of the largest Hub and Spoke networks for STEMI in Italy in the period 2006-2018.

2. Materials and Methods

The Matrix Registry is a single-center non-interventional registry created to evaluate in a prospective fashion demographic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of all-comers patients presenting to our Institution with STEMI and treated with primary PCI. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee and by the Italian Ministry of Health (

http://www.onecare.cup2000.it/telemedicina/percorso-diagnostico-terapeutico-dell’infarto-miocardico-acuto) and was conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each patient (or from relatives in case of the patient’s inability) before the angiogram for participation in the follow-up. We thus conducted a subgroup analysis of the Matrix Registry aiming at evaluating the potential relationship between smoking habit and STEMI-related mortality. In particular we focused on time matter of symptoms evolution to demonstrate differences between subgroups. Our Hub and Spoke network for STEMI in North-western Tuscany, Italy, began in April 2006 with the systematic use of PCI. The population of this 1,658 km2 area is roughly 400,000. About 800 km2 is a rugged mountainous territory, while the remaining area is coastal. This program involved one Hub (Ospedale del Cuore di Massa) and five Spoke centers, one medical helicopter and six advanced life support ambulances, with direct transmission of pre-hospital ECG to the catheterization laboratory (24/7 PCI capability within 30 min of notification) activated by a single-call action. All patients presenting within 12 h of the onset of symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia and new or presumed-new ST-elevation or left bundle-branch block, who were transferred to our PCI hospital and treated with primary PCI from April 1, 2006, to December 31, 2018, were considered for inclusion in this study. Due to the absence of a first aid unit at our Hub center, all patients were transferred from the Spoke center, or directly by EMS. We excluded patients who were transferred and diagnosed with STEMI but not treated with PCI (CABG or medical therapy).

A database dedicated to STEMI patients was created and maintained by the information department of our hospital. Over 200 parameters were included in the data set (medical history, biochemical parameters, as well as clinical, echocardiographic, and angiographic data), collected either manually, through a graphical user interface, or by automatically extracting data from medical records (personal details, time to treatment, outcomes, etc.) [

4]. Some of the parameters were defined as mandatory, without which the patient would be excluded from the study. These parameters were the time of 1) symptom onset leading to medical assistance; 2) first medical contact; 3) catheterization laboratory arrival; and 4) first balloon inflation time. The time from symptom onset to first medical contact was defined decision time (DT), the time from symptom onset to first balloon inflation was defined symptom to balloon time (SBT). Based on SBT patients were divided into five groups: ≤2 h, between 2 and 4 h, between 4 and 6 h, between 6 and 8 h, and between 8 and 12 h.

In 92% of patients (n=2260), it was possible to pinpoint a specific time of symptom onset. It was difficult to determine an accurate onset in the remaining 8% (n=196) of patients, most of whom were elderly and diabetic with atypical symptoms or patients with OHCA. For these patients, in order to be as accurate as possible, we collected the clinical information from relatives and from EMS dispatches.

Mortality data within the intervention hospital was taken from the main database, which also provided systematic information on discharge and transferal of patients to their local hospitals. Data about mortality in the patients’ local hospitals were systematically collected by telephone. For all patients, follow-up information was obtained by conducting a direct phone interview with the patient or his/her general practitioner as well as searching in the mortality database. Follow-up was not possible with 25 patients (0.9%), due to unsuccessful attempts to contact them by phone; they were therefore excluded from the study.

No restrictions on age and sex were applied. Before primary PCI, all patients received intravenous ASA (500 mg) and a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel [600 mg], ticagrelor [180 mg] prasugrel [60 mg]). Ticagrelor was the standard therapy in patients treated after 2011. Unfractionated heparin (70-100 IU/Kg, intra-arterial) was administered in the catheterization laboratory before initiating the diagnostic angiography. From January 2009 onwards, thrombo-aspiration was performed whenever a large thrombus burden was detected [

5,

6]. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa therapy was left to the operators’ discretion in patients with large thrombus burden and/or angiographic complications (distal embolization, no-reflow phenomenon) of primary PCI according to the guidelines [

7,

8]. STEMI was defined by symptoms of myocardial ischemia accompanied by a persistent elevation of the ST segment on the electrocardiogram according to the 4th Universal MI Definition [

9]. Cardiogenic shock was defined as persistent systolic blood pressure ≤ 90mmHg, unresponsive to fluid administration and requiring vasopressors with echocardiographic evidence of severe dysfunction of the left ventricle, over a large infarction area. The use of intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock was encouraged for all suitable patients but was left to operator’s discretion. Culprit vessel TIMI flow grade was assessed after the PCI procedure and procedural success was defined as post-procedural TIMI 3 flows. To assess left and right ventricular systolic function, and rule out any mechanical complications, all patients received two-dimensional echocardiographic evaluation upon arrival in the catheterization laboratory before PCI, within the first 24 h after PCI, and every day during their in-hospital stay. Left ventricular systolic function was determined by Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction, calculated using the biplane Simpson’s method by a trained cardiologist. Subsequent medical treatment included anti-ischemic, lipid-lowering, and antithrombotic drugs was administered to every patient strictly according to current treatment guidelines [

10,

11].

All statistical analyses were conducted with STATA® statistical package, version 13.0 (Stata Corp LP). Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and proportions and compared using Pearson's 𝛘2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The normal distribution of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Francia test and Student's t-test for independent groups was used to compare data with normal distribution, presented as mean values ± SD (σ). To test for possible differences between non-normally distributed variables, the Mann-Whitney test for independent groups was used and the data are presented as medians and inter-quartile ranges [IQR: 25%-75%]. The relationship between general characteristics of the population and SBT groups was assessed by one-way ANOVA and to control for type I error the Scheffe’s adjusted significance level was used. Tukey post-hoc analysis was used to determine differences between groups. A linear relationship between two sets of data has been assessed using Pearson’s product-moment correlation. Univariate and multivariable-adjusted analyses were performed to evaluate the independent contribution of patients' characteristics to in hospital and 1 year follow up, using the main cardiovascular risk factors and all baselines’ variables with a statistically significant difference between groups. We used a parsimonious model including variables with p < 0.10 by the univariate test as a candidate for the multivariate analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as appropriate. Moreover, the association between smoking status and in-hospital mortality was assessed using a 2-tailed Chi-square test.

In order to reduce the imbalance between covariates in the two groups and further assess the effect of smoking in STEMI patients, a propensity score analysis was performed; a logistic regression was performed to obtain propensity score (covariates: male sex, age, diabetes mellitus type II, hypertension, dyslipidemia, history of coronary artery disease in the family, previous cardiovascular interventions, previous acute coronary syndrome, cardiogenic shock at presentation and degree of left ventricular ejection fraction); a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching was done to obtain two comparable groups.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

3. Results

A total of 2,456 STEMI patients treated with primary PCI were enrolled until December 2018. Demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics according to ischemic time are reported in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics at presentation according to different symptom to balloon time groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics at presentation according to different symptom to balloon time groups.

| |

Total

2456 (100) |

Group 1

≤ 2 h

297 (12) |

Group 2

2-4 h

1151 (47) |

Group 3

4-6 h

518 (21) |

Group 4

6-8h

212 (9) |

Group 5

8-12h

278 (11) |

P Value |

| Age, y |

67

[58 - 77] |

66

[58 - 76] |

66

[58 - 76] |

68.5

[59 - 79] |

70

[59 - 80] |

69

[59 - 79] |

0.345 |

| Male |

1792 (73) |

231 (78) |

875 (76) |

354 (68) |

142 (67) |

190 (68) |

0.079 |

| DT, minutes |

73

[33-150] |

20

(15-30) ‡¶* |

50

(40-75) ‡¶* |

120

(90-180) §† |

416

(388-450) §† |

435

(315-650) §† |

< 0.001 |

| Diabetes |

508 (21) |

56 (19) |

220 (19) |

120 (23) |

58 (27) |

54 (19) |

0.086 |

| Hypertension |

1437 (58) |

170 (57) |

650 (56) |

322 (62) |

130 (61) |

165 (59) |

0.905 |

| BMI |

26 [24 - 29] |

26 [24 - 29] |

26 [24 - 29] |

26 [24 - 29] |

26 [24 - 29] |

26 [24 - 28] |

0.897 |

| Dyslipidemia |

985 (40) |

131 (44) |

470 (41) |

196 (38) |

86 (41) |

102 (37) |

0.052 |

| Current smoker |

1007 (41) |

117 (39) |

518 (45) |

198 (38) |

71 (33) |

103 (37) |

0.167 |

| Family history of CAD |

656 (27) |

70 (24) |

322 (28) |

152 (29) |

55 (26) |

57 (20) |

0.266 |

Prior MI

(> 7 days)

|

282 (11) |

35 (12) |

142 (12) |

55 (11) |

25 (12) |

25 (9) |

0.174 |

| Prior PCI/CABG |

266 (11) |

41 (14) |

113 (10) |

45 (9) * |

20 (9) * |

47 (17) ঠ|

< 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock |

150 (6) |

18 (6) |

69 (6) |

38 (7) |

14 (7) |

11 (4) |

0.039 |

| Cardiac arrest pre-PCI |

138 (5) |

21 (7) |

66 (5) |

27 (5) |

7 (4) |

17 (6) |

0.067 |

| LVEF % |

51 [31-60] |

54 [42-60] |

48 [38-57] |

51 [33-55] |

50 [32-55] |

49 [33-60] |

0.078 |

| LVEF < 40% |

968 (39) |

116 (39) |

433 (38) |

211 (41) |

89 (42) |

119 (43) |

0.081 |

| Culprit artery segment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LAD |

1148 (47) |

147 (49) |

533 (46) |

244 (47) |

92 (43) |

132 (47) |

0.506 |

| Circumflex artery |

419 (17) |

41 (14) |

189 (16) |

106 (20) |

40 (19) |

43 (15) |

0.447 |

| Left main artery |

31 (1) |

4 (1) |

13 (2) |

9 (2) |

0 (0) |

5 (2) |

0.520 |

| Right coronary artery |

836 (34) |

104 (35) |

405 (35) |

155 (30) |

77 (36) |

95 (34) |

0.560 |

| Bypass graft |

22 (1) |

1 (1) |

11 (1) |

4 (1) |

3 (2) |

3 (1) |

0.871 |

| Non culprit stenosis > 50% |

710 (29) |

107 (36) |

308 (27) |

150 (29) |

62 (29) |

83 (30) |

0.710 |

| Three Vessels Disease |

236 (11) |

34 (10) |

109 (10) |

56 (10) |

23 (11) |

14 (5) |

0.064 |

Two Vessels

Disease

|

474 (22) |

73 (25) |

199 (19) |

94 (20) |

39 (19) |

69 (25) |

0.095 |

| Single Vessels Disease |

1746 (73) |

190 (71) |

843 (74) |

368 (72) |

150 (74) |

195 (71) |

0.277 |

| Post- procedure TIMI 0-1 |

320 (13) |

39 (13) |

136 (12) |

73 (14) |

30 (14) |

42 (15) |

0.530 |

| Post- procedure TIMI 3 |

1897 (77) |

239 (80) |

906 (79) |

390 (75) |

158 (75) |

204 (73) |

0.316 |

In hospital

mortality

|

95 (4) |

4 (1) |

36 (3) |

27 (5) |

13 (6) |

15 (5) |

0.008 |

One - year

mortality

|

201 (8) |

22 (8) |

89 (8) |

47 (10) |

25 (12) |

18 (7) |

0.378 |

The median age of our population was 67 years [58 – 77, range 28–99]. Of note, women were significantly older than men (76 [65 - 83] vs 64 [56 - 73] years - p<0.0001). Median ischemic time for the entire population was 215 [IQR: 150-317] minutes. Again, women experienced significantly longer SBT (239 [163 - 346] vs 206 [147 - 305] min - p<0.0001) than men. In the whole population, a shorter SBT was associated with better revascularisation; a median of 210 [150 - 312] min was reported for TIMI flow 3 group while a median of 225 [157 - 355] min was reported for TIMI flow < 2 group with a significant difference (p<0.01). Only 5% of smoking patients experienced cardiogenic shock versus 7% of non-smoking patients (p=0.013). No differences appeared among the other Killip class.

Complete comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between groups are reported in

Table 2.

Smoking habit was associated with younger age (61 [52 - 69] vs 72 [63 - 81] years – p<0.001) and smokers’ SBT appears to be shorter than that of non-smokers (203 [147 - 299] vs 220 [154 - 334] min – p<0.002). Moreover, DT differs among groups, in fact, smoker patients showed less hesitation in seeking medical assistance compared to non-smoking patients in a significant fashion (60 [30-135] vs 77 [36-170] minutes – p<0.001). No differences in terms of post-procedural TIMI 3 and of history of previous MI between smoking and non-smoking patients were observed.

A total of 95 (4%) and 201 (8%) patients died in-hospital and at 1-year follow-up, respectively. In-hospital and one-year follow-up mortality were significantly higher among women than men (8% vs 2% - p<0.0001 and 14% vs 7% - p < 0.0001 respectively). Patients who experienced higher in-hospital mortality were those with a longer SBT (264 [IQR: 190 - 420] min vs 212 [IQR: 150 - 315] min - p=0.0038), while no differences in this relationship appeared at 1-year follow-up (226 [IQR: 165 - 324] min vs 210 [IQR: 149 - 214] min - p = 0.103)”.

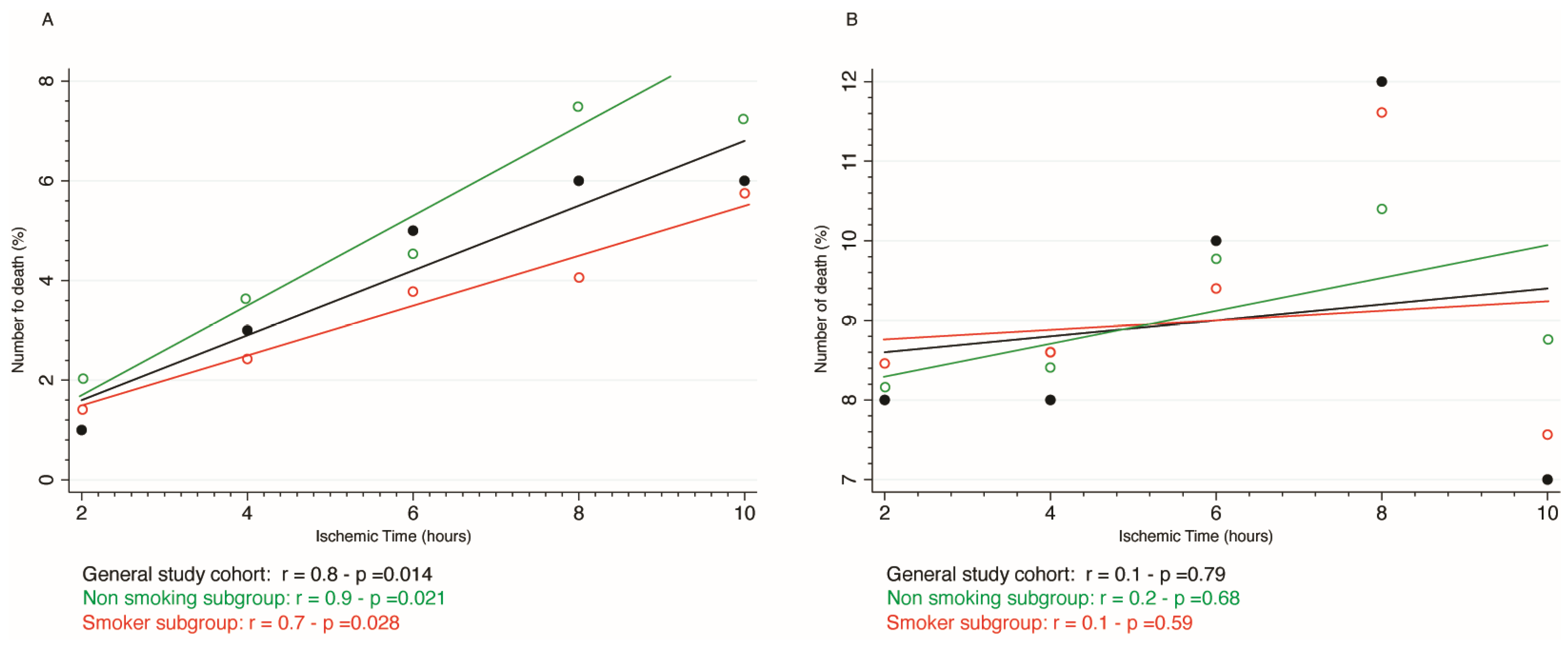

As shown in

Figure 1, in-hospital mortality increased linearly according to SBT both in smoking and non-smoking subgroup (r = 0.7 - p =0.028 and r = 0.9 - p =0.021, respectively.) whilst such a trend was not observed for mortality at 1-year follow-up among groups (r=0.2 – p=0.59 for smokers and r=0.1 – p=0.68 for non-smoking subgroup respectively). Based on this finding, we calculated that in-hospital mortality increased by 2.8% for every 2 h delay.

Univariate and Multivariable Adjusted analysis were used to detect the relationship between variables and in-hospital (

Table 3) and one - year follow-up mortality (

Table 4). After multivariable analysis, SBT [OR:1.01 (95% CI: 1.01-1.02) - p<0.05] appeared as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality together with age [OR 1.06 (95% CI: 1.04 - 1.09) - p<0.001], post-PCI TIMI<2 [OR:5.62 (95% CI: 3.49 – 9.04) - p<0.001], cardiac arrest [OR: 1.10 (95% CI: (1.05 – 1.31) - p<0.01] and cardiogenic shock [OR: 2.01 (95% CI: (1.73 – 2.13)) - p<0.01], whilst smoker status [OR:0.37 (95% CI: 0.18 – 0.75) - p<0.01] and male sex [OR:0.53 (95% CI: 0.32 - 0.88) - p<0.01] emerged as protective variables. Looking at one-year follow up, at multivariate analysis only age was an independent predictor of mortality [OR:1.10 (95% CI: 1.08 – 1.12) - p < 0.001]. Compared with non-smokers, smoker patients had lower in hospital (1.5% vs 6% - p < 0.001) and at 1-year follow-up mortality (5% vs 11% - p <0.01).

3.1. Propensity Score Analysis

Propensity score matching yielded two comparable groups (smokers vs non-smokers) with no significant differences in baseline characteristics (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 1). As for in-hospital outcomes (Supplemental Table 2), there were no differences regarding symptoms-to-balloon times, door-to-balloon, and decision times, as well as no differences in the immediate reperfusion state; the in-hospital death was higher in non-smokers group (3.4% vs 1.7%; p=0.024) and remained higher also at 1 year follow-up (9-5% vs 5.1%; p<0.001). At univariable analysis (Supplemental Table 3) we found that in-hospital mortality was associated with age (OR 1.04, 95% CI [1.02-1.07]; p=0.001), previous cardiovascular interventions (OR 2.59, 95% CI [1.23-5.03]; p=0.007), cardiogenic shock (OR 42.8, 95% CI [22.5-83.7]; p<0.001), increased symptoms-to-balloon time (OR 1.02, 95% CI [1.02-1.03]; p<0.001) and decision time (OR 1.04, 95% CI [1.01-1.02]; p=0.013), as well as low TIMI score at the end of the procedure (TIMI 1 or TIMI 2: OR 5.16, 95% CI [2.84 - 9.55]; p<0.001). Conversely, smoking habit (OR 0.49, 95% CI [0.26 - 0.91]; p=0.026) and TIMI 3 score (OR 0.19, 95% CI [0.10 - 0.25]; p<0.001), were associated with decreased in-hospital mortality. At multivariable analysis (Supplemental Table 4), age (OR 1.04, 95% CI [1.02-1.07]; p=0.015), cardiogenic shock (OR 42.9, 95% CI [20.8-92.1]; p<0.001) and low TIMI score (OR 3.77, 95% CI [1.86 - 7.74]; p<0.001) were associated with in-hospital mortality, while smoking habit was still associated with reduced mortality (OR 0.44, 95% CI [0.20 - 0.90]; p=0.026). At 1-year follow-up, age (HR 1.04, 95% CI [1.02 - 1.06]; p<0.001) was independently associated with mortality and smoking (HR 0.54, 95% CI [0.37 - 0.78]; p<0.001) with a reduced rate of death.

4. Discussion

The so-called “smoker’s paradox” was introduced into scientific arena more than two decades ago[

12,

13,

14,

15] to describe the counterintuitive phenomenon of lower mortality in smoker patients presenting with STEMI compared to non-smokers. The paradoxical nature of this evidence is in the sight of all and some analyses have tried to deconstruct the evidence of this paradox by showing its inconsistencies[

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. More in details, while some authors have proposed to explain the counter-intuitive beneficial effect of smoking in STEMI with an enhanced myocardial preconditioning– thus being associated with a decreased final infarct size [

21,

22,

23], others have shown that, among STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI, smoking status does not affect infarct size[

24]. However, some aspects remain nowadays unsolved and there is not a univocal satisfactory explanation. Our data, derived from a large cohort of consecutive STEMI patients, aim at shedding new light on the enigmatic protection related to smoking status in the setting of STEMI.

4.1. Smoking Habit and Younger Age

One of the most common hypotheses explaining the observed “protection” of smoking patients in the setting of STEMI relates to the importance of a younger age of smokers rather than smoking itself. As previously reported, indeed, smokers are usually younger at the time of their first cardiovascular events, with fewer atherosclerotic risk factors and comorbidities compared with nonsmokers[

17]. In our population we confirm that smoker patients were younger and had a better prognosis, both in terms of lower in-hospital and one-year mortality. Specifically, smoking patients develop STEMI about 10 years earlier than non-smoking, as previously reported by Björn Redfors et al. [

25]. From a pathophysiologic perspective, smokers have increased platelet aggregation [

26,

27], increased fibrinogen, and decreased fibrinolytic activity compared with non-smokers [

27], creating a state of hypercoagulability that predisposes to acute thrombosis [

28]. Smoking also induces endothelial dysfunction [

29] and neutrophil activation [

28], causes oxidant injury [

29], increases fibrinogen levels, and causes platelet activation [

27], all of which increase the rate of atherosclerosis and plaque progression by direct or indirect effects[

2].. Additionally, smoking can trigger spasms in the coronary arteries, further exacerbating the risk of acute coronary syndrome. All these conditions can be related to accelerated atherosclerosis, and the fact that smokers were admitted to the hospital for STEMI about 10 years before non-smokers, indicates that premature coronary atherothrombosis is the high price they pay for smoking [

30,

31]. Besides, as previously reported, there was no association of smoking with infarct size or microvascular obstruction MVO, and that smoker patients were at greater risk of reinfarction [

18,

32]. Our multivariable analysis confirmed that, among others, not only younger age but also smoking status were both associated with decreased in-hospital mortality.

4.2. Smoking Habit and Lower Ischemic Time

Animal and clinical studies have shown more myocardial salvage and better outcomes with a reduction in SBT [

33]. In fact, as previously reported, SBT could be considered the new gold standard for STEMI care [

34]. Stratifying our population, we found a strong relationship between SBT and in-hospital mortality. For every 2-h delay, mortality significantly and linearly increased by 2.8 %. Conversely, such a trend was not observed for mortality at 1-year follow-up, which is likely dependent on other factors. SBT is influenced by several factors, such as the patient’s ability to promptly recognize signs and symptoms of heart attack[

35,

36], together with a rapid decision to seek medical care (i.e., short decision time), as well as a fast diagnosis[

37] and quick transport to the most appropriate medical facility, to restore coronary blood flow[

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. In our study, we observed that decision time and SBT in smokers was significantly shorter than in non-smokers thus, in turn, leading to a benefit of STEMI-related mortality. As specified in the methods, in 92% of patients it was possible to pinpoint a specific time of symptom onset and in the remaining patients, most of whom were elderly and diabetic with atypical symptoms or patients with OHCA, in order to be as accurate as possible, we collected the clinical information from relatives and from EMS dispatches. One could speculate that, for smokers more than for non-smokers, the awareness of being at risk of coronary artery disease may allow a rapid link of symptoms to heart problem and, consequently, lead the patients to a prompter and quicker seek for help, thus finally leading to a decrease of decision time and the ischemic time. This may explain the shorter decision time that we found in our smoker patients to seek medical care which helps to shorten the ischemic time. Non-smokers are more frequently elderly and diabetics, thus with atypical STEMI presentation or lower chest pain. However, again we underline that multivariate analysis revealed that smoking habit was independently associated with a reduced in-hospital mortality.

4.3. Smoking-Related Protection in STEMI: Not Just Younger Age and Shorted Ischemic Time

In order to investigate a possible “direct” smoking-related cardioprotective effect in STEMI we performed a propensity score matching analysis allowing a direct comparison of two different groups - smokers vs non-smokers - with no significant differences in baseline characteristics. More specifically, this analysis aimed at ruling out the possible indirect effect of younger age and shorter ischemic time as mediators of the observed better outcome of smokers vs non-smokers. Again, our additional analysis confirmed that in-hospital death was higher in non-smokers group (3.4% vs 1.7%; p=0.024) and remained higher also at 1 year follow-up (9-5% vs 5.1%; p<0.001). More surprisingly, both at univariable and multivariable analysis we found that smoking habit was still associated with reduced mortality, both in-hospital and at 1-year follow-up.

Evidence from literature support the observation of a lower mortality rate in smokers with STEMI receiving thrombolytic therapy [

44,

45,

46,

47]. As well as in our study, after adjusting for initial risks, this association remains significant in some studies [

48], while others don’t show lowered mortality after corrections [

44,

45,

46,

47]. It is hypothesized that smoking's impact on increased blood clotting rather than plaque vulnerability results in better response to this treatment. Smoking can lead to a tendency for clotting caused by endothelial dysfunction, amplified platelet activity, raised fibrinogen levels, and disproportionate thrombin generation [

49]. Furthermore, fibrin cross-linking is affected by cigarette components [

50]. Thus, in smokers the predominant cause of STEMI could be on thrombogenic, not atherogenic, basis making thrombolytic therapy more effective. Consequently, this might influence the effectiveness of various antithrombotic therapies. Notably, an analysis of the HORIZONS-AMI trial revealed that among STEMI patients receiving pPCI, bivalirudin monotherapy resulted in reduced 30-day and 1-year mortality in smokers but not in non-smokers when compared to unfractionated heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors [

51].

Some studies have also indicated that nicotine can lead to increased expression of P2Y12 receptors in human platelet lysates, which may elucidate the impact of smoking on platelet inhibition [

52]. This could explain a possible greater response to P2Y12 inhibitor such clopidogrel used in acute phase of STEMI and pPCI and a different clinical efficacy in smokers versus non-smokers.

4.4. Study Limitations

The results of this clinical prospective registry should be considered in light of some limitations. First, this is a single-centre registry with a long period of inclusion and the follow-up time was limited to 1 year after index events. We lost contact with 25 out of our total 2336 patients for a variety of reasons, including unsuccessful attempts to reach patients by phone even after several attempts and due to privacy preferences of the patients concerned. Second, information on smoking status was available only at the time of the STEMI and not during follow-up. Given the beneficial impact of smoking cessation, information on changes in smoking status over the course of the study would have provided additional useful information. Moreover, packs smoked per day, and total pack-years were not available, making a more comprehensive differentiation between patients impossible. Furthermore, home-therapy was not considered among the mandatory fields of the registry. So, we did not have enough and factual data to be included in our tables.

5. Conclusions

Our data reinforce the enigma of the so-called “smoker’s paradox”. In our cohort we confirm that smoking patients presenting with STEMI are younger and have a lower ischemic time than non-smoker patients. However, the reduced both in-hospital and 1-year follow up mortality observed in smoking patients cannot be fully explained by different baseline characteristics of smokers. A different pathogenetic effect of smoking on STEMI mechanism is also conceivable and future studies should definitively establish whether pathophysiological differences between smokers and non-smokers with STEMI contribute to this paradoxical link. Indeed, the true reason behind this unusual outcome remains uncertain. This apparent phenomenon that smokers with STEMI might have better short-term outcomes should not be seen as a favourable effect or advantage of smoking. The negative effects of smoking are well-documented, and any differences in outcomes are likely overshadowed by the long-term mortality caused by smoking. It is crucial to continue intensive efforts to promote smoking cessation. A strong public awareness campaign, bringing the message that a combination of medical treatments and behavioural counselling improves the likelihood of successfully quitting, is mandatory.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: post-matching Baseline Characteristics; Table S2: post-matching Operative Data; Table S3: post-matching Univariate Analysis for In-hospital mortality; Table S4: psot-matching Multivariable analysis for in-hospital mortality; Figure S1: pre- and post-matching plot of absolute standardized mean differences (SMD) across the covariates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.P. and A.R. De C.; methodology, U.P., A.R. De C., G.T. and G.B.; validation, U.P., A.R. De C., G.T. and G.B.; formal analysis, U.P. and A.R. De C.; investigation, U.P. and A.R. De C.; data curation, U.P., A.R. De C., F.D., M.R., G.B. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, U.P. and A.R. De C..; writing— review and editing, U.P. and A.R. De C.; visualization, G.A. and C.de G..; supervision, S.B. and G.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fondazione Gabriele Monasterio – Regione Toscana, Massa, Italy.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from each patient (or from relatives in case of the patient’s inability) before the angiogram for participation in the follow-up.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Roberto Martini for the graphics and the Cath Lab staff of the Fondazione Gabriele Monasterio – Regione Toscana, Massa, Italy for their precious help in collecting data.

Conflicts of Interest

Sergio Berti is proctor for St. Jude Medical and Edwards Lifesciences LLC. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

References

- Andrikopoulos, G.K.; Richter, D.J.; Dilaveris, P.E.; Pipilis, A.; Zaharoulis, A.; Gialafos, J.E.; Toutouzas, P.K.; Chimonas, E.T. In-Hospital Mortality of Habitual Cigarette Smokers after Acute Myocardial Infarction; the “Smoker’s Paradox” in a Countrywide Study. Eur Heart J 2001, 22, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, R.; Masci, P.G.; Francone, M.; Claus, P.; Barison, A.; Carbone, I.; Agati, L.; Galea, N.; Janssens, S.; Bogaert, J. Impact of Active Smoking on Myocardial Infarction Severity in Reperfused ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients: The Smoker’s Paradox Revisited. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 2756–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; Reports of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta (GA), 2014.

- Taddei, A.; Paradossi, U.; Rocca, E.; Carducci, T.; Mangione, M.; Dalmiani, S.; Laws, E.; Marchi, M.; Badiali, B.; Berti, S. Information System for Assessing Health Care in Acute Myocardial Infarction. In Proceedings of the 2012 Computing in Cardiology; September 2012; pp. 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Guardiola, F.; Rossi, A.; Serra, A.; Garcia, B.; Rumoroso, J.R.; Iñiguez, A.; Vaquerizo, B.; Triano, J.L.; Sierra, G.; Bruguera, J.; et al. Angiographic Quantification of Thrombus in ST-Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction Presenting with an Occluded Infarct-Related Artery and Its Relationship with Results of Percutaneous Intervention. J Interv Cardiol 2009, 22, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardella, G.; Mancone, M.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Agati, L.; Scardala, R.; Carbone, I.; Francone, M.; Di Roma, A.; Benedetti, G.; Conti, G.; et al. Thrombus Aspiration during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Improves Myocardial Reperfusion and Reduces Infarct Size: The EXPIRA (Thrombectomy with Export Catheter in Infarct-Related Artery during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) Prospective, Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009, 53, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, J.S.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Bischoff, J.M.; Bittl, J.A.; Cohen, M.G.; DiMaio, J.M.; Don, C.W.; et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e18–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, F.-J.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Ahlsson, A.; Alfonso, F.; Banning, A.P.; Benedetto, U.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.-P.; Falk, V.; Head, S.J.; et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Myocardial Revascularization. Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 87–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D. Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72, 2231–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting with ST-Segment Elevation: The Task Force for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting with ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: Lipid Modification to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmers, C. Short and Long-Term Prognostic Indices in Acute Myocardial Infarction. A Study of 606 Patients Initially Treated in a Coronary Care Unit. Acta Med Scand Suppl 1973, 555, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, T.L.; Gilpin, E.; Ahnve, S.; Henning, H.; Ross, J. Smoking Status at the Time of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Subsequent Prognosis. Am Heart J 1985, 110, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, D.; Dawber, T.R. The Influence of Cigarette Smoking on Prognosis after a First Myocardial Infarction. A Report from the Framingham Study. J Chronic Dis 1978, 31, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinblatt, E.; Shapiro, S.; Frank, C.W.; Sager, R.V. Prognosis of Men after First Myocardial Infarction: Mortality and First Recurrence in Relation to Selected Parameters. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1968, 58, 1329–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joner, M.; Cassese, S. The “Smoker’s Paradox”: The Closer You Look, the Less You See. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019, 12, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Mintz, G.S.; Généreux, P.; Liu, M.; McAndrew, T.; Redfors, B.; Madhavan, M.V.; Leon, M.B.; Stone, G.W. The Smoker’s Paradox Revisited: A Patient-Level Pooled Analysis of 18 Randomized Controlled Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019, 12, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.D. Deconstructing the Paradox of Smoking and Improved Short-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 1755–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtane, A.J.; Kelly, C.R. Clearing the Air on the “Smoker’s Paradox”. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015, 65, 1116–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, S.A.; Islam, N.; Sulaiman, K.; Alsheikh-Ali, A.A.; Singh, R.; Al-Qahtani, A.; Asaad, N.; AlHabib, K.F.; Al-Zakwani, I.; Al-Jarallah, M.; et al. Demystifying Smoker’s Paradox: A Propensity Score-Weighted Analysis in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e013056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, Y.; Canseco, D.C.; Thet, S.; Abdisalaam, S.; Asaithamby, A.; Santos, C.X.; Shah, A.M.; Zhang, H.; Faber, J.E.; Kinter, M.T.; et al. Hypoxia Induces Heart Regeneration in Adult Mice. Nature 2017, 541, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.W.; Selker, H.P.; Thiele, H.; Patel, M.R.; Udelson, J.E.; Ohman, E.M.; Maehara, A.; Eitel, I.; Granger, C.B.; Jenkins, P.L.; et al. Relationship Between Infarct Size and Outcomes Following Primary PCI: Patient-Level Analysis From 10 Randomized Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cohen, M.V.; Downey, J.M. Mechanism of Cardioprotection by Early Ischemic Preconditioning. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2010, 24, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, G.; Parodi, G.; Sciagrà, R.; Bellandi, B.; Comito, V.; Vergara, R.; Migliorini, A.; Valenti, R.; Antoniucci, D. Smoking and Infarct Size among STEMI Patients Undergoing Primary Angioplasty. Atherosclerosis 2014, 233, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfors, B.; Furer, A.; Selker, H.P.; Thiele, H.; Patel, M.R.; Chen, S.; Udelson, J.E.; Ohman, E.M.; Eitel, I.; Granger, C.B.; et al. Effect of Smoking on Outcomes of Primary PCI in Patients With STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, P.H. An Acute Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Platelet Function. A Possible Link between Smoking and Arterial Thrombosis. Circulation 1973, 48, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benowitz, N.L.; Fitzgerald, G.A.; Wilson, M.; Zhang, Q. Nicotine Effects on Eicosanoid Formation and Hemostatic Function: Comparison of Transdermal Nicotine and Cigarette Smoking. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993, 22, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benowitz, N.L.; Gourlay, S.G. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Nicotine: Implications for Nicotine Replacement Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997, 29, 1422–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael Pittilo, R. Cigarette Smoking, Endothelial Injury and Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Exp Pathol 2000, 81, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, M.M.; Jørgensen, S.; Kjøller, E.; Videbaek, J.; Køber, L.; Torp-Pedersen, C. Age-Distribution, Risk Factors and Mortality in Smokers and Non-Smokers with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Review. TRACE Study Group. Danish Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation. J Cardiovasc Risk 1999, 6, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøttcher, M.; Falk, E. Pathology of the Coronary Arteries in Smokers and Non-Smokers. J Cardiovasc Risk 1999, 6, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, K.A.; Roifman, I. STEMI, the Smoker’s Paradox, and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging: It’s All a Case of Smoke and Mirrors. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, K.A.; Lowe, J.E.; Rasmussen, M.M.; Jennings, R.B. The Wavefront Phenomenon of Ischemic Cell Death. 1. Myocardial Infarct Size vs Duration of Coronary Occlusion in Dogs. Circulation 1977, 56, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denktas, A.E.; Anderson, H.V.; McCarthy, J.; Smalling, R.W. Total Ischemic Time: The Correct Focus of Attention for Optimal ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Care. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011, 4, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapka, J.G.; Oakes, J.M.; Simons-Morton, D.G.; Mann, N.C.; Goldberg, R.; Sellers, D.E.; Estabrook, B.; Gilliland, J.; Linares, A.C.; Benjamin-Garner, R.; et al. Missed Opportunities to Impact Fast Response to AMI Symptoms. Patient Educ Couns 2000, 40, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedges, J.R.; Feldman, H.A.; Bittner, V.; Goldberg, R.J.; Zapka, J.; Osganian, S.K.; Murray, D.M.; Simons-Morton, D.G.; Linares, A.; Williams, J.; et al. Impact of Community Intervention to Reduce Patient Delay Time on Use of Reperfusion Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) Trial. REACT Study Group. Acad Emerg Med 2000, 7, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, J.P.; Portnay, E.L.; Wang, Y.; McNamara, R.L.; Herrin, J.; Bradley, E.H.; Magid, D.J.; Blaney, M.E.; Canto, J.G.; Krumholz, H.M.; et al. The Pre-Hospital Electrocardiogram and Time to Reperfusion in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction, 2000-2002: Findings from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction-4. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006, 47, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, G.; Suryapranata, H.; Zijlstra, F.; van ’t Hof, A.W.J.; Hoorntje, J.C.A.; Gosselink, A.T.M.; Dambrink, J.H.; de Boer, M.J. ; ZWOLLE Myocardial Infarction Study Group Symptom-Onset-to-Balloon Time and Mortality in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated by Primary Angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003, 42, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.H.; Herrin, J.; Wang, Y.; Barton, B.A.; Webster, T.R.; Mattera, J.A.; Roumanis, S.A.; Curtis, J.P.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Magid, D.J.; et al. Strategies for Reducing the Door-to-Balloon Time in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 2308–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.H.; Curry, L.A.; Webster, T.R.; Mattera, J.A.; Roumanis, S.A.; Radford, M.J.; McNamara, R.L.; Barton, B.A.; Berg, D.N.; Krumholz, H.M. Achieving Rapid Door-to-Balloon Times: How Top Hospitals Improve Complex Clinical Systems. Circulation 2006, 113, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le May, M.R.; So, D.Y.; Dionne, R.; Glover, C.A.; Froeschl, M.P.V.; Wells, G.A.; Davies, R.F.; Sherrard, H.L.; Maloney, J.; Marquis, J.-F.; et al. A Citywide Protocol for Primary PCI in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med 2008, 358, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, U.N.; Johnson, M.L.; Ramsey, C.; Khot, M.B.; Todd, R.; Shaikh, S.R.; Berg, W.J. Emergency Department Physician Activation of the Catheterization Laboratory and Immediate Transfer to an Immediately Available Catheterization Laboratory Reduce Door-to-Balloon Time in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2007, 116, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.H.; Rihal, C.S.; Gersh, B.J.; Haro, L.H.; Bjerke, C.M.; Lennon, R.J.; Lim, C.-C.; Bresnahan, J.F.; Jaffe, A.S.; Holmes, D.R.; et al. Regional Systems of Care to Optimize Timeliness of Reperfusion Therapy for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The Mayo Clinic STEMI Protocol. Circulation 2007, 116, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbash, G.I.; Reiner, J.; White, H.D.; Wilcox, R.G.; Armstrong, P.W.; Sadowski, Z.; Morris, D.; Aylward, P.; Woodlief, L.H.; Topol, E.J. Evaluation of Paradoxic Beneficial Effects of Smoking in Patients Receiving Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction: Mechanism of the “Smoker’s Paradox” from the GUSTO-I Trial, with Angiographic Insights. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue-Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995, 26, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbash, G.I.; White, H.D.; Modan, M.; Diaz, R.; Hampton, J.R.; Heikkila, J.; Kristinsson, A.; Moulopoulos, S.; Paolasso, E.A.; Van der Werf, T. Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Young--the Role of Smoking. The Investigators of the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase Mortality Trial. Eur Heart J 1995, 16, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zahger, D.; Cercek, B.; Cannon, C.P.; Jordan, M.; Davis, V.; Braunwald, E.; Shah, P.K. How Do Smokers Differ from Nonsmokers in Their Response to Thrombolysis? (The TIMI-4 Trial). Am J Cardiol 1995, 75, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grines, C.L.; Topol, E.J.; O’Neill, W.W.; George, B.S.; Kereiakes, D.; Phillips, H.R.; Leimberger, J.D.; Woodlief, L.H.; Califf, R.M. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Outcome after Thrombolytic Therapy for Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 1995, 91, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbash, G.I.; White, H.D.; Modan, M.; Diaz, R.; Hampton, J.R.; Heikkila, J.; Kristinsson, A.; Moulopoulos, S.; Paolasso, E.A.; Van der Werf, T. Significance of Smoking in Patients Receiving Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Experience Gleaned from the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase Mortality Trial. Circulation 1993, 87, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambola, A.; Osende, J.; Hathcock, J.; Degen, M.; Nemerson, Y.; Fuster, V.; Crandall, J.; Badimon, J.J. Role of Risk Factors in the Modulation of Tissue Factor Activity and Blood Thrombogenicity. Circulation 2003, 107, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanakis, D.K.; Laurent, P.; Janoff, A. Cigarette Smoke Contains Anticoagulants against Fibrin Aggregation and Factor XIIIa in Plasma. Science 1982, 217, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K.; Nikolsky, E.; Lansky, A.J.; Dangas, G.; Witzenbichler, B.; Parise, H.; Guagliumi, G.; Kornowski, R.; Claessen, B.E.; Fahy, M.; et al. Impact of Smoking on Outcomes of Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (from the HORIZONS-AMI Trial). Am J Cardiol 2011, 108, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, G.; Kontos, J.L.; Eckman, D.M.; Wesley-Farrington, D.; Sane, D.C. Nicotine Upregulates the Expression of P2Y12 on Vascular Cells and Megakaryoblasts. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2006, 22, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).