1. Introduction

The global prevalence of burn injuries is on the rise, driven by factors such as increased industrialization, urbanization, and a higher incidence of traumatic events. In the United States of America (USA), burns rank as the 4th leading cause of mortality, requiring medical attention for approximately 2.5 million patients each year. Annually, more than 100,000 burn patients are hospitalized, while 40 % - 45 % of them are usually children and 25 % of these children are younger than 20 years old. Approximately 6,000 burn patients may die annually, and permanent disability occurs in 50 % of these patients [

1,

2,

3].

Apart from the immediate physical trauma associated with burns, there is a growing concern about the development of hypertrophic scars or keloids, leading to functional impairment and aesthetic challenges. Furthermore, the psychological impact of burn scars is increasingly recognized, as individuals grapple with issues such as self-esteem, body image, and social integration. Despite advances in burn care and societal progress, the incidence and severity of burns have not shown a corresponding decrease, resulting in an escalating number of patients with post-burn sequelae [

4,

5].

Post-burn injuries often lead to various sensory discomforts, including prickling, burning sensation, numbness, and stinging that occur in the post-burn state [

6]. Among the discomforts, post-burn pruritus is a highly common and distressing problem affecting individuals who have suffered burn injuries. Post-burn scar can all cause long-lasting pruritus, often associated with burning or piercing sensations [

7]. In those who sustain burn injuries, itch is present in about 87 % of patients after 3 months, in 70 % of patients after 1 year, and in 67 % of patients after 2 years [

8]. Itching has been shown to significantly impact the quality of life for people with burns, causing disturbances in sleep, impairments in daily activities, and affecting psychosocial well-being [

9]. As in many inflammatory skin diseases, itching has been shown to affect the quality of life of people with burns, leading to sleep disturbances, impairments of daily activities, and psychosocial well-being [

10,

11]. Post-burn pruritus may decrease over time but may last more than a few years [

12]. As burns can cover large body areas, the suffering from itching can be tremendous. In addition, when a patient with post-burn pruritus scratches the skin, the damage to the skin barrier becomes more severe.

Currently, various moisturizers are employed to treat burn scars, including Pantenol-ratiopharm® (Ratiopharm GmbH, Ulm, Germany), Alhydran® (Asclepios GmbH, Breisgau, Germany), and Theresienöl® (Theresienöl GmbH, Kufstein, Austria). Pantenol-ratiopharm® is an occlusive ointment used for post-burn scar care, focusing on minimizing Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL). Its key component, Dexpanthenol, is renowned for its wound-healing properties [

13,

14]. Alhydran® is an aloe vera-based moisturizer frequently employed in natural medicine, primarily for skin hydration and scar management. Notably, it has shown efficacy, particularly when used in a gel form, in treating wounds [

15,

16,

17]. Therrienöl® is an ointment consisting of apple and lily extracts, along with tocopheryl acetate (vitamin E), which is known for promoting cell repair and the regeneration of damaged skin [

18].

Nevertheless, the ingredients and characteristics of topical agents used to treat post-burn scar have not been standardized yet. While there is a high demand for specialized cosmetic formulations addressing burn scars, research on topical agents designed to alleviate symptoms and signs associated with these scars remains limited. One prior study demonstrated the beneficial effects of arginine glutamate ion pair (known as RE:pair) on wound healing and enhancement of skin elasticity following CO

2 laser irradiation. Glutamate, an ingredient in RE: pair, has been shown to promote keratinocyte proliferation [

19]. In the skin, glutamate plays a vital role in metabolism and function, including collagen biosynthesis in fibroblasts [

20]. In the epidermis, glutamate contributes to the formation of cornified envelope (CE), which acts as a barrier to the environment through the action of transglutaminase enzymes [

21]. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of a cosmetic formulation containing arginine glutamate ion pair on burn scar severity, post-burn dryness, itching, pain, and patient satisfaction among individuals who have undergone acute burn treatment for partial-thickness burns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Materials

We recruited 20 patients [15 male (75 %), 5 female (25 %); average age 48.35 ± 13.13 years] aged 18 or older with post-burn scar who were undergoing follow-up (F/U) after primary treatment at the Burn Center of Hallym University Hangang Sacred Heart Hospital. Prior to cosmetic formulation application, the patient's post-burn scar were scored “mild to severe” based on the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) score. Treatment and F / U evaluations were conducted between May to December 2023.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) those with acute inflammatory skin disease and moderate or severe symptomatic infection at the site of observation; (2) those with uncontrolled systemic or chronic disease; (3) those who take immunotherapy, biologics including oral corticosteroid within 4th weeks before registration; (4) those who take topical corticosteroid or topical immunosuppressant within 1 week before registration; and (5) those who are required to administer a prohibited drug in combination in this clinical trial.

The cosmetic formulation containing RE:pair is a cream-type emollient containing 1.8 % ion-paired arginine and glutamate in a molar ratio of 1:1. RE:pair formula is a basic type oil-in-water (O / W) based cosmetic formula 23.

2.2. Study Design

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki, and this clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Hangang Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB no. HG2023-016). Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Registered clinical trial subjects were provided with the test preparation on the date of clinical trial (Visit 1; Baseline), and clinical trial subjects applied RE:pair formula twice a day in both mornings and evenings on the burn area from the date of clinical trial (Visit 1; Baseline). If necessary, sunscreen can be used, and hot baths are prohibited other than showers within 15 minutes, and the product is applied immediately after a shower. The clinical trial subjects visited the institution for evaluation on the 2nd weeks (Visit 2; Day 14 ± 3) and 4th weeks (Visit 3; Day 28 ± 3).

2.3. Outcome Measures

Clinical evaluations with photographs were performed at baseline, 2nd weeks (Visit 2; Day 14 ± 3) and 4th weeks (Visit 3; Day 28 ± 3). To evaluate the efficacy, itching, and pain, Transepidermal water loss (TEWL), Skin hydration level, and VSS were measured on the lesional site using the Tewameter and Corneometer. Two blinded trained dermatologists evaluated the scores using clinical photos. Using the Tewometer® TM300 probe (Courage & Khazaka GmbH, Cologne, Germany) and the Corneometer® CM825 probe (Courage & Khazaka GmbH, Cologne, Germany), the device was placed on the skin to be perpendicular to the skin surface within 2 minutes from both lesions, and the TEWL and skin hydration were measured, respectively.

The patients were evaluated by dividing the subjective itching and pain into 0 to 10 stages. Additional clinical assessments were performed based on the VSS. The VSS consists of the following four components: vascularity, pigmentation, height (ranging from 0 to 3), and pliability (ranging from 0 to 5). A score of zero indicates normal skin, while a maximum score indicates the worst possible lesional site. These indexes were measured on the skin for 2 min in a room with constant temperature (20-24℃) and humidity (28-38%).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The differences in the itching and pain, TEWL, skin hydration, and VSS were evaluated using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for multiple comparisons. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are summarized as mean, SD, median, minimum, and maximum values, and unless otherwise specified, all statistical tests were conducted with a two-sided test with a type 1 error rate of α = 5 %.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

Twenty patients were enrolled in this study. Subjects completed this trial [15 male (75 %), 5 female (25 %); average age 48.35 ± 13.13 years] (

Table 1). The degree of burn scar of the patient before application was the degree to control mild to severe based on Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) score. The mean length of the lesional site was 7.81 cm and severe lesions (13 / 17) were more than 5 cm.

3.2. The Efficacy of the RE:Pair Formula for Relieving Itching and Pain

The degree of post-burn scar in the experiment participants were mild to severe. Since not all patients had itching from the baseline, among patients who complained of itching, the number was measured by dividing it into 0 - 10 stages to confirm the trend of decreasing itching.

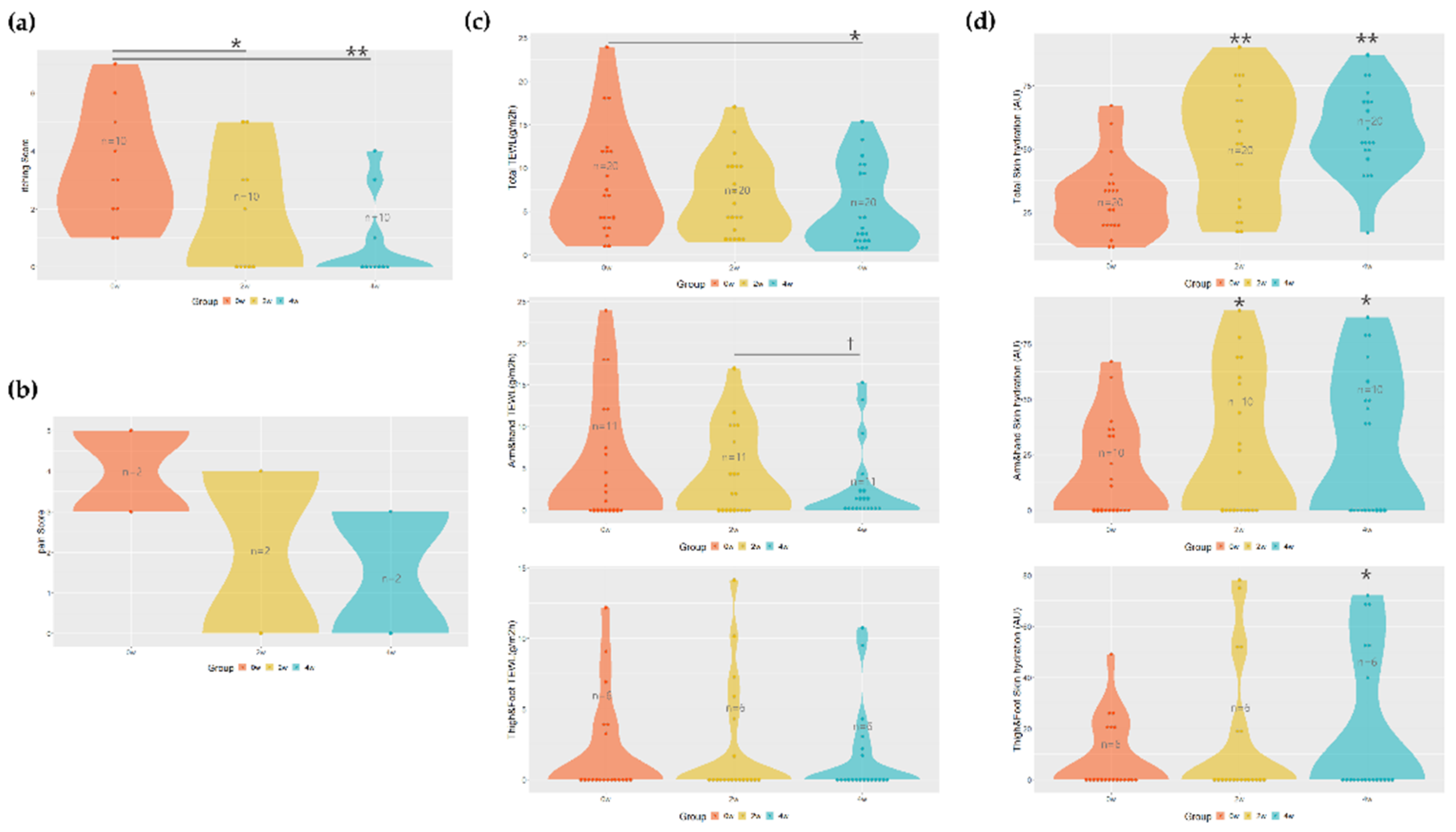

The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for itching score decreased from an average of 3.4 ± 2 before application to 1.8 ± 2 at 2 weeks after application and 0.8 ± 1.47 at 4 weeks after application, indicating a tendency to decrease to an average of 47 % (

p = 0.0133) after 2 weeks and an average of 76 % (

p = 0.0005) after 4 weeks of application compared to before application. In particular, the score of the patient with the highest itching before application was 7 points, and it was also confirmed that the itching score was noticeably reduced to 3 points after 4 weeks of use

(Figure 1a

).

In the case of pain, almost all people did not have it before application, but in those with pain (n=2), it decreased from an average of 4 points before application to 3 points after application, but significance was not confirmed (Figure 1b).

3.3. Changes in Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL) and Skin Hydration with the RE:Pair Formula

The amount of transepidermal water loss (TEWL) was measured to evaluate the change in skin barrier function. We tried to obtain more reliable experimental results by comparing the normal area and the burn scar area respectively. In the case of the normal area, the values of 4.766 ± 3.27 before application, 4.61 ± 4.05 after 2nd weeks of application, and 5.381 ± 5.723 after 4th weeks of application were shown, and there was no effect compared to before application.

The average of TEWL values in the scar area was confirmed to be 8.27 ± 6.15 before application, 6.719 ± 4.44 after 2nd weeks of application, and 5.378 ± 4.632 after 4th weeks of application, which improved by 35 % (p = 0.0419) after 4th weeks of application. As measuring the effect on each area, the arms and hands showed values of 9.91 ± 3.54 before application, 7.68 ± 4.41 after 2nd weeks of application, and 4.74 ± 3.8 after 4th weeks of application. There was a tendency to improve by 22 % after 2nd weeks of application and 52 % after 4th weeks, and significantly improved by more than 38 % (p = 0.0420) between 2nd and 4th weeks. When performed on the legs (thighs + feet), it was confirmed as 6.54 ± 3.54 before application, 7.23 ± 4.41 after 2nd weeks of application, and 5.25 ± 3.88 after 4th weeks of application, compared to before application, 19 % improvement. Still, no effectiveness was confirmed (Figure 1c).

In addition, we also evaluated the efficacy by comparing the skin hydration, between the normal area and the burn scar area, respectively. In the case of the normal area, 35.85 ± 14.43 before application, 40.1 ± 16.51 after 2nd weeks, and 40.9 ± 13.44 after 4th weeks, there was no significant difference compared to before application. The scar area was confirmed to be 30.07 ± 14.69 before application, 52.2 ± 22.8 after 2nd weeks of application, and 56.8 ± 16.46 after 4th weeks of application, which increased by 41 % (p = 0.0021) after 2nd weeks and 45 % (p = 0.0012) after 4th weeks compared to before application. As measuring the effect on each area, the arms and hands showed values of 35.3 ± 2.64 before application, 54.1 ± 30 after 2nd weeks of application, 59.5 ± 2.08 after 4th weeks of application, which increased by 34 % after 2nd weeks (p = 0.0488) and 40 % (p = 0.0371) after 4th weeks compared to before application. When performed on the legs (thighs + feet), it was found to be 27 ± 2.64 before application, 49.16 ± 30.04 after 2nd weeks of application, and 59 ± 2.08 after 4th weeks. It was confirmed that it was significantly improved by 54 % (p = 0.0313) after 4th weeks of application compared to before (Figure 1d).

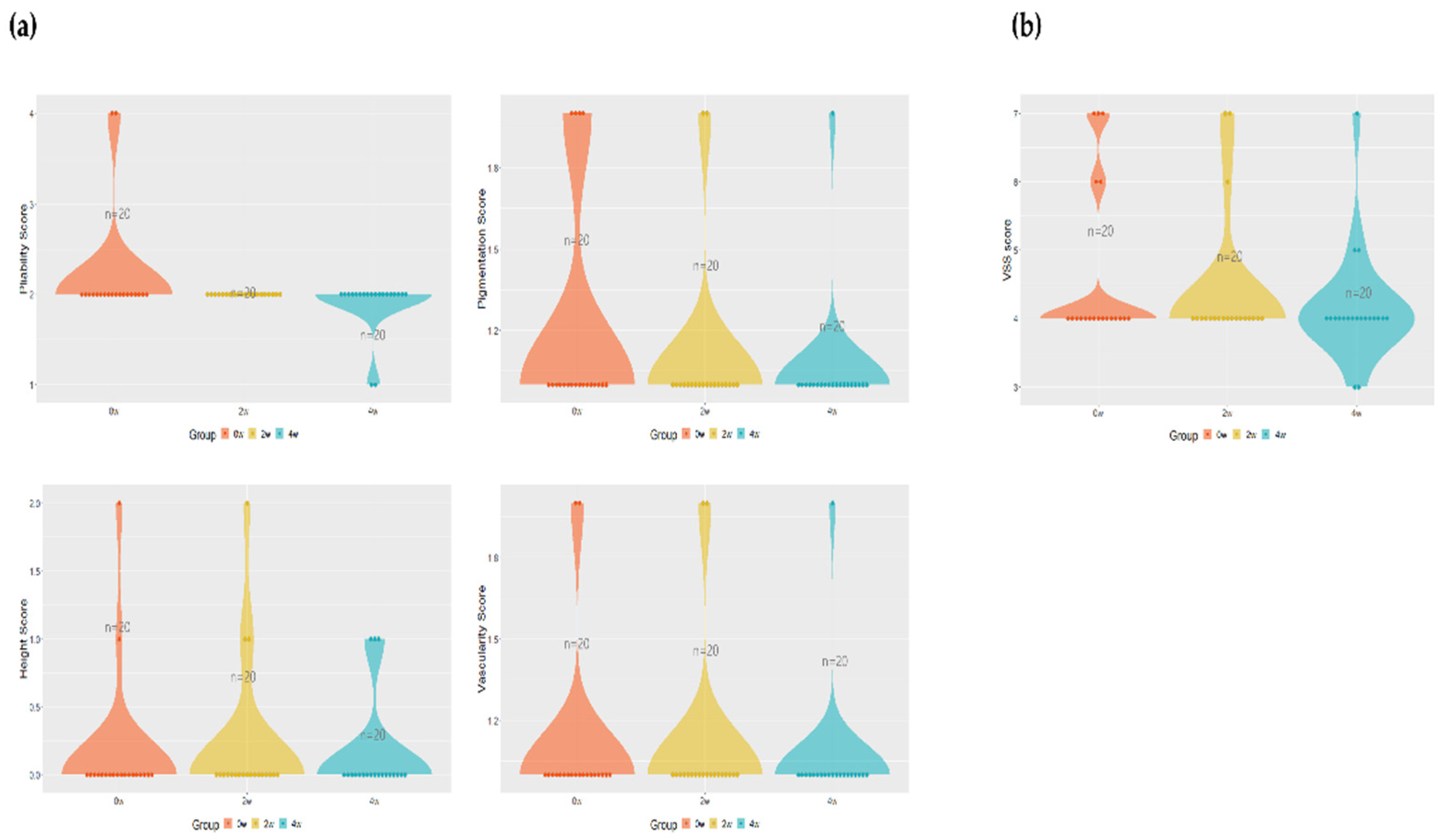

3.4. Comparison of Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) before and after application

To evaluate the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) the subject's pigment, thickness, erythema, and flexibility were calculated numerically. The pigment decreased from 1.1 ± 0.3 before and 2nd weeks after application to 1.1 ± 0.3, 1.05 ± 0.22 after 4th weeks of application, decreasing on average by 4.54 % after 4th weeks of application compared to before application, and the thickness was confirmed to be 0.15 ± 0.48 before application, 0.2 ± 0.52, and 0.15 ± 0.36 after 4th weeks of application. In the case of erythema, it was confirmed that it decreased to values of 1.2 ± 0.41, 2nd weeks after application and 4th weeks after application, respectively, of 1.1 ± 0.30, and 1.05 ± 0.22 after application, showing a tendency to decrease by 12 % in total after 4th weeks compared to before application. Flexibility also decreased by an average of 13.63 % to 2.2 ± 0.61, 2nd weeks after application, and 2 ± 0.3, respectively, 2nd weeks and 4th weeks after application (

Figure 2a).

Calculating the above four items by VSS, it decreased from 4.65 ± 1.18 before application to 4.4 ± 0.99 and 4.15 ± 0.81 after 2nd weeks of application, decreasing by 5.68 % on average after 2nd weeks of application compared to before application, and decreasing by 5.68 % on average after 2nd weeks to 4th weeks of application compared to before total application, but no significance was confirmed (Figure 2b).

4. Discussion

Burned skin undergoes an acute wound-healing reaction and then becomes scar tissue after several months [

22]. Itching is a common occurrence during the wound-healing process following burns [

23]. This study attempted to improve scar quality, clinical efficacy, and patient satisfaction by applying preparations to the lesion site against patients with 2nd-degree (partial thickness) burns after the acute treatment.

The representative active ingredient of cosmetic formulation used in this experiment is an ion paired with arginine and glutamate. The degree of improvement in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for itching score and pain in the scar area following the application of this formula was evaluated. Only some patients had itching (n=10), so the initial itching mean score was lower than expected. Nevertheless, itching was significantly reduced in patients with itching. Pain tended to decrease, but this was not statistically significant. Therefore, it can be considered that this preparation was effective in alleviating pruritus in burn patients.

To evaluate the skin barrier function, transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and skin hydration of stratum corneum were measured. It assesses the integrity of the skin barrier and identifies TEWL to identify healthy or diseased skin. A higher TEWL may indicate damage to the protective barrier or failure to function properly, leading to skin damage that may allow more water to pass through [

24].

More reliable experimental results were attempted by comparing the normal area and the burn scar area, revealing no significant difference in the normal area but a significant improvement in the scar area. Specifically, the measurements were 8.27 ± 6.15 before applying the formulation, 6.719 ± 4.44 after 2nd weeks of application, and 5.378 ± 4.632 after 4th weeks of application, indicating a significant 35 % improvement after 4th weeks of application. The skin moisture content also showed a significant increase after 2nd weeks and 40 % after 4th weeks, respectively, compared to before application. When evaluating barrier function before and after application on arms and legs, it was confirmed that the barrier function improved even after the 2nd and 4th weeks of application.

To assess clinical improvement, Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) was compared before application, 2nd weeks after application, and 4th weeks after application. Compared to before application, the average decreased by 5.68 % after 2nd weeks of application, and the average decreased by 5.68 % even after 2nd weeks to 4th weeks of application, which decreased by 10 % on average after the 4th weeks of application compared to before the total application. Still, the significance was not confirmed. This is due to the nature of VSS, which evaluates the color and thickness of burn scars. It appears that significant changes in already stabilized scars with the topical agent alone are difficult to observe within 4 weeks. This trend aligns with previous studies. In the evaluation of the subjects' overall satisfaction with the application area, all evaluators evaluated "excellent" 2nd weeks after application compared to before application and "excellent" 4th weeks after application, and it was observed that the patient's symptom improvement by continuous use was also highly satisfactory.

In conclusion, the present study provides promising insights into the potential efficacy of cosmetic formulas with arginine glutamate ion pair in the management of post-burn scar. The observed improvements in itching, pain, TEWL, and skin hydration are indicative of its positive impact on patient outcomes. Notably, the high satisfaction scores among the study participants underscore the product's acceptability and usability in a clinical setting.

Generally, well-formulated moisturizer can restore the barrier function to relieve itching [

25]. The use of moisturizer for burn scars is not only necessary for massaging scars, but also for addressing the additional changed skin properties of scar tissue, so it should be used as an agent to help moisturize the skin while minimizing irritation, protecting the skin barrier, and reducing skin hydration. There are currently no specific recommendations for moisturizers for scar management after burn injuries and are based on the clinical experience of burn specialists such as medical staff. Very few of them are based on scientific evidence [

26].

There a several pilot studies assessing the effectiveness of topical moisturizers with post-burn patients. In one study, patients with acute burns using bath oil with colloidal oatmeal tended to have significantly less itching and fewer requests for antihistamines compared with patients using bath oil with liquid paraffin. This is because colloidal oatmeal with moisturizing ingredients improves patient comfort and reduces the risk of skin damage caused by scratches when healing burn wounds [

27]. Emollients include basic moisturizers, aloe vera, and coconut oil, which moisturize the skin and improve the skin barrier function [

28]. Emollients are considered anti-sensitizers in that they soften the stratum corneum of dry skin and are essential for healing burn wounds, improving skin barrier function, and facilitating healing [

29]. To confirm the effectiveness of moisturizers in post-burn scar management, many studies have been conducted on various moisturizers, including water-based cream BP, wax and herbal oil creams, silicone creams, paraffin/oil/mineral oil products, and aloe vera gels, and scar formation, skin decomposition, and water loss have been confirmed [

30]. However, studies conducted to date have not identified the optimal moisturizer for managing post-burn scar. This consistency emphasizes the complexity of scar healing and the multifactorial nature of scar assessment [

31].

RE:pair formula consists of arginine and glutamate, and some studies have already reported that these two components are effective in wound improvement and healing. Arginine is a semi-essential amino acid in human protein biosynthesis and is metabolized by arginase I or nitric oxide synthase II (NOS II) and is known to play an important role in cell division, collagen synthesis, wound healing, and skin immunity [

32]. Among them, L-arginine has been effective in the treatment of severe skin wounds such as scars caused by post-burns and ultraviolet (UV)-induced erythema in previous reports [

33]. One study concluded that L-arginine was more effective in reducing T helper 1 cells (Th1) cytokine release and increasing Th2 cytokine production in the infection phase of severe burns [

34]. Glutamate, a transitional form of glutamine by glutaminase (glutamate-degrading enzyme), is known as an amino acid involved in the central nervous system and plays an important role in the growth of keratinocytes and fibroblasts [

35,

36]. Like L-arginine, glutamate is known to be effective in treating post-burn injury [

37]. Despite these advantages, glutamate has a low solubility in water [7.5 g/L (20 °C)], making it difficult to include it in high concentrations in cosmetics and moisture ointments. This formula overcomes the limitations by creating an emollient with ion pair of arginine and glutamate and increasing the skin permeability of both amino acids [

19].

Since the moisturizer used in this study incorporates various cosmetic mechanisms alongside the active ingredients, it remains unclear whether the efficacy ingredients specifically contributed to improving skin barrier function and alleviating burn-induced itching. Moving forward, future research endeavors could explore the extended benefits of arginine glutamate ion pair over more extended periods and consider a more extensive, diverse patient population. Additionally, investigating the underlying mechanisms and potential synergies with other scar management modalities may offer a more comprehensive understanding of the product's therapeutic effects.

5. Conclusions

Arginine and glutamate were highlighted as beneficial ingredients for wound healing and skin health, with prior studies supporting their effectiveness. This study aimed to assess the quality, clinical efficacy, and satisfaction regarding scars in patients with partial-thickness (2nd-degree) burns who were treated in the acute phase of burns using an emollient containing arginine glutamate ion pair. The study aimed to improve scar quality, clinical efficacy, and patient satisfaction in second-degree burn patients. Although the degree of post-burn scar in the experimental participants was “mild or severe”, the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for itching score was significantly reduced in some itching patients compared to the beginning by applying cosmetic formulations with arginine and glutamate ion pairs (named as RE:pair). While there was the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) score decreased, the reduction did not reach statistical significance due to the limitation of the post-burn scar properites evaluation of VSS. Patient satisfaction with the application area was high, with all participants rating it as "excellent." Future research directions include exploring long-term effects, diverse patient populations, underlying mechanisms, and potential synergies with other scar management approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.O.K., M.S.K. and I.S.K.; Methodology, Software, and Validation, B.Y.C., C.W.P. and J.Y.U.; Formal Analysis, H.B.K.; Formulation, S.W.P. and N.S.S.; Investigation, and Resources, I.S.K. and J.G.W.; Data curation, C.W.P.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, H.B.K.; Writing-Review & Editing, S.Y.L., M.S.K. and H.O.K.; Project Administration, H.O.K. and I.S.K.; Funding Acquisition, H.O.K. and I.S.K.; Supervision, N.S.S. and N.G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (grant number NRF-2022R1A2C2007739), a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number HP23C0201) and Hallym University Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki, and this clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Hangang Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB no. HG2023-016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that no conflict of interest could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported RE:pair formula manufactured by LG Household & Healthcare (LG H&H).

References

- Barss, P. Injury prevention: an international perspective epidemiology, surveillance, and policy. USA: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- Rossignol, A.M.; Locke, J.; Burke, J. Paediatric burn injuries in New England, USA. Burns. 1990, 16, 41–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research NRCCoT, Research CoT, Medicine Io. Injury in America: a continuing public health problem: Natl Academy Pr. 1985.

- Smolle, C.; Cambiaso-Daniel, J.; Forbes, A.A.; Wurzer, P.; Hundeshagen, G.; Branski, L.K.; Huss, F.; Kamolz, L.P. Recent trends in burn epidemiology worldwide: A systematic review. Burns. 2017, 43, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodha, P.; Shah, B.; Karia, S.; De Sousa, A. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Ptsd) Following Burn Injuries: A Comprehensive Clinical Review. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2020, 33, 276–287. [Google Scholar]

- Van Loey, N.E.; Bremer, M.; Faber, A.W.; Middelkoop, E.; Nieuwenhuis, M.K. Itching following burns: Epidemiology and predictors. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stumpf, A.; Sta¨nder, S. Neuropathic itch: diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther. 2013, 26, 104–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, M.; Fields-Blache, C.; Luterman, A. Severe itching in the patient with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1991, 12, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, B.Y.; Kim, H.B.; Jung, M.J.; Kang, S.Y.; Kwak, I.S.; Park, C.W.; Kim, H.O. Post-Burn Pruritus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, S.E.; Patterson, D.R. Treating sleep problems in patients with burn injuries: practical considerations. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004, 25, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, L.; McAdams, T.; Morgan, R.; Parshley, P.F.; Pike, R.C.; Riggs, P.; Carpenter, J.E. Pruritus in burns: a descriptive study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988, 9, 305–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Willebrand, M.; Low, A.; Dyster-Aas, J.; Kildal, M.; Andersson, G.; Ekselius, L.; Gerdin, B. Pruritus, personality traits and coping in long-term follow-up of burn-injured patients. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2004, 84, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorski, J.; Proksch, E.; Baron, J.M.; Schmid, D.; Zhang, L. Dexpanthenol in Wound Healing after Medical and Cosmetic Interventions (Postprocedure Wound Healing). Pharmaceuticals. 2020, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, E.; Nissen, H.P. Dexpanthenol enhances skin barrier repair and reduces inflammation after sodium lauryl sulphate-induced irritation. J Dermatol Treat. 2002, 13, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maenthaisong, R.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Niruntraporn, S.; Kongkaew, C. The efficacy of aloe vera used for burn wound healing: A systematic review. Burns. 2007, 33, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyapraphatsara, N.; Jirakulchaiwong, S.; Thirawarapan, S.; Manonukul, J. The efficacy of Aloe vera cream in the treatment of first, second and third degree burns in mice. Phytomedicine. 1996, 2, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatpou, D.; Mehrabi, F.; Rahzani, K.; Aminiyan, A. The Effect of Aloe Vera Clinical Trials on Prevention and Healing of Skin Wound: A Systematic Review. Iran J Med Sci. 2019, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strashilov, S.; Slavchev, S.; Aljowder, A.; Vasileva, P.; Postelnicu-Gherasim, S.; Kostov, S.; Yordanov, A. Austrian natural ointment (Theresienöl®) with a high potential in wound healing—A European review. Wound Med. 2020, 30, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.C.; Won, J.G.; Seo, J.H.; Kwon, O.S.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, M.S.; Park, S.W. Effects of arginine glutamate (RE:pair) on wound healing and skin elasticity improvement after CO2 laser irradiation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5037–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karna, E.; Miltyk, W.; Wołczyński, S.; Pałka, J.A. The potential mechanism for glutamine-induced collagen biosynthesis in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2001, 130, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candi, E.; Knight, R.A.; Panatta, E.; Smirnov, A.; Melino, G. Cornification of the skin: A non-apoptotic cell death mechanism. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz-Gospodarek, A.; Kozioł, M.; Tobiasz, M.; Baj, J.; Radzikowska-Büchner, E.; Przekora, A. Burn Wound Healing: Clinical Complications, Medical Care, Treatment, and Dressing Types: The Current State of Knowledge for Clinical Practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19(3), 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.J.; Boyce, S.T. Burn Wound Healing and Tissue Engineering. J Burn Care Res. 2017, 38, e605–e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, M.; Gabriel, S.; Lichterfeld-Kottner, A.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Kottner, J. Transepidermal water loss in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Br J Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.S. The Skin Barrier and Moisturizer. J Skin Barrier Res. 2007, 9, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, T.; Kurmis, R.; Munn, Z.; Heath, K.; Greenwood, J. Moisturisers in scar management following burn: A survey report. Burns. 2017, 43, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, J.D.; Clayton, J.; Muller, M.J. The reduction of itch during burn wound healing. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2001, 22, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachariah, J.R.; Rao, A.L.; Prabha, R.; Gupta, A.K.; Paul, M.K.; Lamba, S. Post burn pruritus - a review of current treatment options. Burns. 2012, 38, 621–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, E.; Yosipovitch, G. Post-Burn Pruritus and Its Management—Current and New Avenues for Treatment. Curr Trauma Rep. 2019, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.B.; Gupta, G.K. A four-arm, double-blind, randomized and placebo- controlled study of pregabalin in the management of post-burn pruritus. Burns. 2013, 39, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, T.; Kurmis, R.; Munn, Z.; Heath, K.; Greenwood, J.E. The effectiveness of moisturizers in the management of burn scars following burn injury: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015, 13, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Koussa, H.; El Mais, N.; Maalouf, H.; Abi-Habib, R.; El-Sibai, M. Arginine deprivation: a potential therapeutic for cancer cell metastasis? A review. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliconstantinos, G.; Villiotou, V.; Stavrides, J.C. Inhibition of ultraviolet B-induced skin erythema by N-nitro-L-arginine and N-monomethyl-L-arginine. J Dermatol Sci. 1997, 15, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Peng, X.; Wang, P.; Huang, Y.S.; Wang, S.L. [Effects of different doses of L-arginine on the serum levels of helper T lymphocyte 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytokines in severely burned patients]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2009, 25, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nieweld, C.; Summer, R. Activated Fibroblasts: Gluttonous for Glutamine. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019, 61, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; O'Leary, E.M.; Witt, L.J.; Tian, Y.; Gökalp, G.A.; Meliton, A.Y.; Dulin, N.O.; Mutlu, G.M. Glutamine Metabolism Is Required for Collagen Protein Synthesis in Lung Fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019, 61, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.M.; Binz, P.A.; Roux, C.; Charrière, M.; Scaletta, C.; Raffoul, W.; Applegate, L.A.; Pantet, O. Exudative glutamine losses contribute to high needs after burn injury. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022, 46, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).