1. Introduction

When clients arrive and need assistance from servers, a simple queueing structure is in place. If there are no open servers, patrons can join a queue; the queue discipline dictates the order in which patrons are served. When designing or enhancing service systems, these models aid in the computation of performance metrics.

Longer wait times are a result of higher utilisation levels, and delays get longer as utilisation rises. Variability and system size also matter; larger systems have shorter delays and more variable systems have longer delays at any given utilisation level. These ideas have effects on service system evaluation and capacity planning [

1].

A typical model for arrivals in queueing systems is the Poisson process. It is assumed that consumers arrive one at a time, and that the probability of arriving at any given moment is independent of both the time and possibility of arriving prior to other customers. This model is often applicable in various contexts, such as emergency rooms and customer service call centers, and can be tested for goodness of fit using statistical measures [

2].

In the context of steady (non-time dependent) queues, namely these queues with non-time dependent probability density function. For example, the

or Erlang delay model is a commonly used queueing model in service systems, i.e., the assumption is that there will be one line serving the same servers, with an infinite amount of waiting room. In this model, service durations, including patient stays or provider times, are considered to have an exponential distribution, and client arrivals is Poissonian [

3].

The

model is still able to produce appropriate estimates of delay even in cases where the actual coefficient of variation (CV) of service time deviates somewhat from one. The

model, however, may either overestimate or underestimate actual delays if the CV differs significantly from one. The average delay can be computed using the

system formula, another well-known none-time dependent queue, in such scenarios involving a Poissonian arrival process with only one server [

2].

1.1. 𝑴/𝑴/∞. Queueing System and the Computation of the Common Average Time for Unsaturated Site Visitors Flows Beneath Double-Parking Situations

Double parking (DP) violations of industrial trucks whilst they load and dump at transport places with inadequate curb side area may have huge poor effect on site visitors. Motivated by the need to examine such effect on urban streets, [

4] make use of parking violation facts for New York City in conjunction with discipline facts accrued the usage of video recording and adopts a complete modelling technique that mixes to be had facts with varieties of fashions. Another implied approach was the micro-simulation version [

4] advanced and calibrated to examine personal and mixed outcomes of diverse explanatory variables. The research [

4] employed a macroscopic

queueing version and micro-simulation for estimating common tour time with inside the presence of double-parking activities.

Under uncongested site visitors` situations without downstream blocking off, making use of the queueing version produced an amazing match with the sphere facts. Overall, the queueing version is a powerful technique to compute the common average time for unsaturated site visitors flows beneath double-parking situations. Micro-simulation is a greater effective device than the queueing version for comparing such congested situations and may be used to study person and mixed outcomes of diverse explanatory variables.

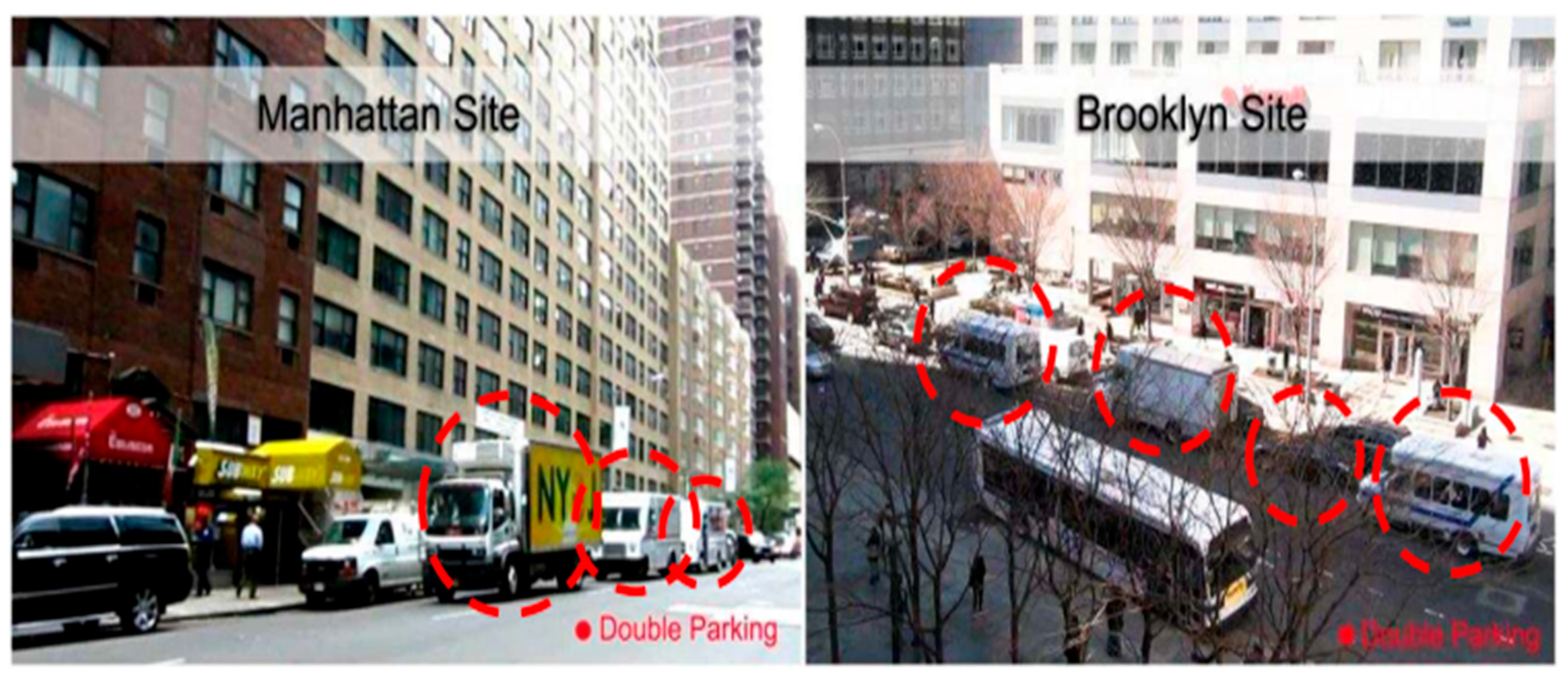

Figure 1.

How DP occurs in the sites under investigation [

4].

Figure 1.

How DP occurs in the sites under investigation [

4].

1.2. Application of Birth–Death Process to Quantitively Interpret the Wavelet Dynamics in Atrial Fibrillation and Phase Singularity

It has been hypothesized that the determined range of PS or wavelets in Atrial Fibrillation (AF) might be ruled with the aid of using a not unusual set of renewal rate constants

(for PS or wavelet formation) and

(PS or wavelet destruction), with steady-state population dynamics modelled as an M/M/∞ birth–death manner. It has been demonstrated [

5]:

(1) that and may be blended in a Markov manner to as it should be a version of the determined common range and population distribution of PS and wavelets in all structures at unique scales of mapping; and

(2) that slowing of the constants denoting rates, namely and is related to slower mixing rates of the birth–death matrix, presenting an interpretation of spontaneous AF termination.

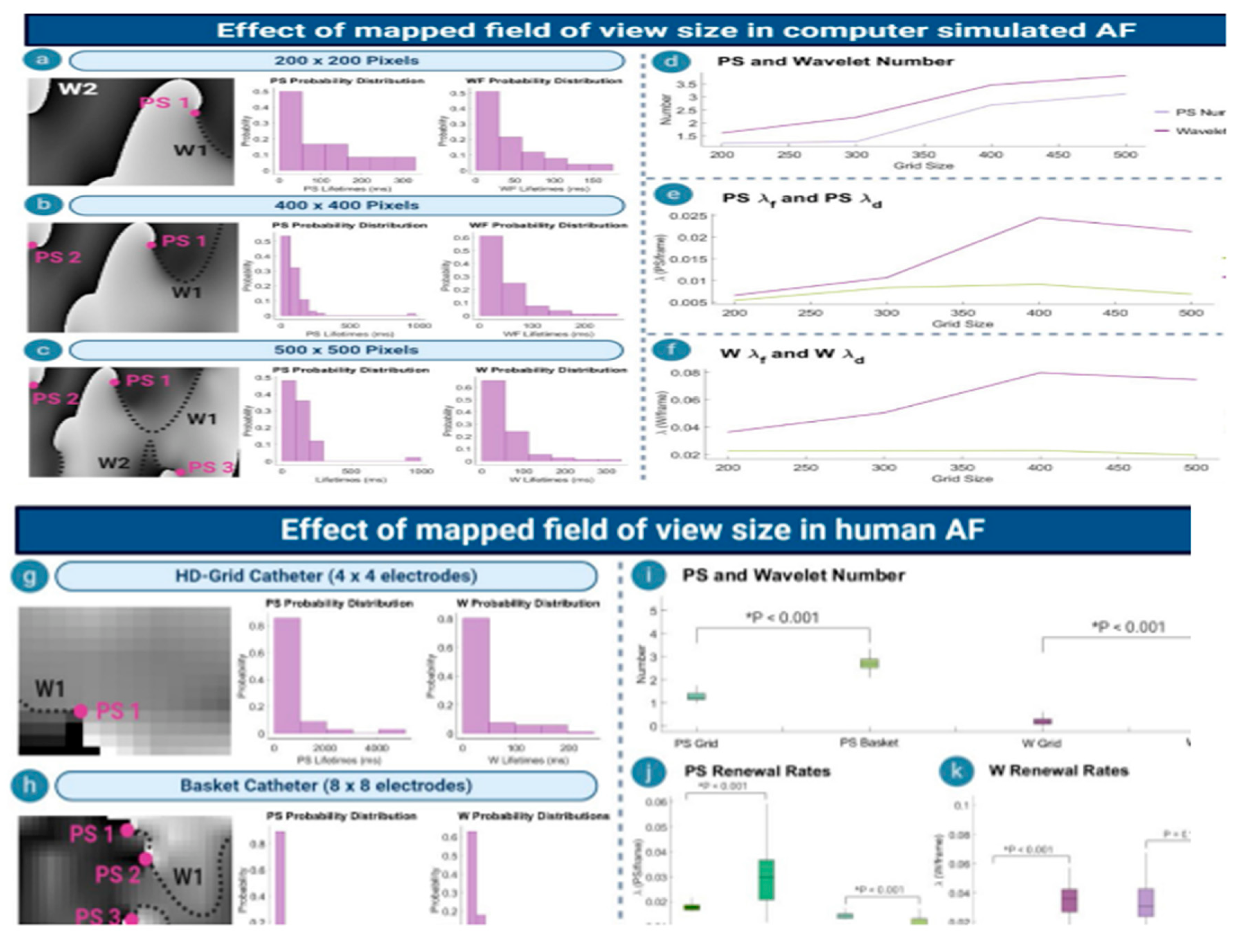

Figure 2.

The birth-death process of a transient

queueing system [

5].

Figure 2.

The birth-death process of a transient

queueing system [

5].

It is worth mentioning that

and

(PS rates of formation and destruction respectively) are related by the following steady-state equation of the

birth–death [

6]

provided that

serves as the average number of PS and wavelets. Additionally, the PS and wavelet population distribution is characterized by the steady state probability

[

6] of getting a wavelet population or a phase singularity with size

is determined by:

Figure 3.

How a mapped field impacts view size [

8]

.

Figure 3.

How a mapped field impacts view size [

8]

.

It has been conjectured by [

5] that both Equations (1) and (2) provide a strong characterization of the overall dynamics of PS and wavelet population.

To understand and identify PS and wavelet population dynamics in AF,

birth–death approaches provide a unique quantitatively expressive architecture. There are opportunities for scientific application because this conceptual paradigm [

7] has been demonstrated to work in a variety of AF studies at unique scales and mapping densities.

1.3. Information Length Theory

Shannon entropy is not the best descriptor [

8] of a time series’ statistical variations, which has made using other unique information theoretic notions, including Fisher Information [

9,

10,

11], highly motivating. Differential entropy [

12], Kullback-Leibler divergence (KD) [

13], or information length (IL) [

14,

15]. By using IL, the total number of statistical variances for a specified temporal range can be found. Compared to other information metrics such as differential entropy, IL is preferred because it highlights the evolution path dependency between two states (PDFs) [

16]. Time-dependent probability density functions (PDFs) provide the ability to trace time series evolution and measure variability [

8], which is the basis of the IL metric's attractiveness.

Additionally, IL’s formalism introduces a fascinating connection between information geometry and stochastic processes [

17]. More interestingly, IL has numerous applications for quantum, fluid, and biological processes [

18]. On the other hand, IL metric was the real motivation behind the provision of a novel info-geometric measure of casual information rate [

19]. Its effects on the creation of entropy or free energy in the non-autonomous Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process highlight the significance of IL for stochastic thermodynamics [

20]. In conclusion, [

21,

22,

23] provide an examination of the interval learning (IL) computation of linear stochastic autonomous processes. This broadens the scope of application, enabling IL to be used for the abruption of event prediction and facilitating application to different engineering contexts.

1.4. IL as a Concept

Mathematically speaking, if

serves as a nth- order stochastic variable and

is a time-dependent PDF of

, then the Information Length

corresponding to its evolution from the initial time

to the final time

is devised by:

provided that

serves as the root-mean- squared fluctuating energy rate.

Having a closer look at (3), it is essential to note that

serves as a dynamic temporal unit which provides the correlation time over which the changes of

take place [

16]

. Furthermore , defines the statistical space’s time unit. Having said that,

, quantifies the information velocity [

18].

It is preferable to compute the underlying value of the mathematical model of the related physical process to comprehend the meaning of

. Taking the Langevin equation-described first-order stochastic process into consideration:

serves as a random variable,

defines a deterministic force,

represents a short-correlated random force satisfying that:

where

serves as the amplitude (temperature) of the deterministic force

It is to be noted that Equation (6) is so popular to be used as a descriptor of the motion of a particle under a harmonic potential in the form:

Following [

23,

24], it is found that:

provided that

Considering Equation (4), it is clear that

is dependent on the changes in both mean and variance defined by the corresponding dynamics of Equation (3), portraying

three-dimensional space variations, namely

as in

Figure 4, where the variation of the information velocity,

would occur along the path starting initially from the state probability density function

to the final state at

as a descriptor of the speed limit from the statistical deviations of the observables [

16].

Figure 4.

A graph depicting the evolution of

over time

.

computes the total amount of statistical changes on

from

to

[

8].

Figure 4.

A graph depicting the evolution of

over time

.

computes the total amount of statistical changes on

from

to

[

8].

Fundamentally, employing differential entropy [

12], may not enable us to observe the occurring temporal statistical variations. This is a direct implication of the locality’s deficiency since differential entropy is mainly for the quantification of the differences between any two given PDFs disregarding any intermediate states [

17]. In a different symbolism, it only notifies us of the differences that have an influence on the underlying system's general development. IL

, on the other hand, measures any localised changes that occur along the system's course [

14,

17]. More crucially, IL has been touted as a cutting-edge technique for depicting an attractor structure and as a potent metric that can unite geometry and stochasticity [

20,

21]. From the point of stable equilibrium, the equivalent value of

would grow linearly depending on where the starting state's mean PDF

is located [

15,

24]. Notably, this strongly underlines that IL preserves the underlying Gaussian process' linear geometry by utilising Equation (6). More importantly, this particular property is lost when employing any other information metric [

17,

20]

. By using definition, this emphasises that IL is a one-dimensional, model-free measure (3). Since IL is independent of data type, it may be devised by calculating the time series’ time-variant PDF [

8].

The road of this current paper reads: A spotlight introduction is presented in

Section 1. The key findings are established in

Section 2. Some challenging open problems, conclusion, and future research work are given in

Section 3.

2. The Upper and Lower Bounds of The Data Information Length of Transient Queuing System

In this section, an exposition of a novel link between Information Length Theory (ILT) and Transient Queueing Systems (TQSs) is undertaken by deriving both upper and lower bounds of the data information length of a transient queuing system. In this context, it is revealed that if serves as the time-dependent server utilization of the transient queuing system, then the latter obtained upper and lower bounds(are both (-dependent, Additionally, a typical numerical experiment is conjectured to illustrate the significant impact of time on behaviour of the devised for different values of.

2.1. The Poisson Process

One of the most popular counting [

25] methods is the Poisson process. It is typically employed in situations when we are counting the occurrences of specific events that seem to occur at a certain rate but are completely random (without a certain structure). For instance, let's say we know from past data that there are two earthquakes that happen in a specific region every month. The timing of earthquakes appears to be completely random except for this information. Thus, we draw the conclusion that the Poisson process may serve as a useful earthquake model. Models have

Photons arriving on a photodiode.

The quantity of auto accidents at a location or in a region.

The position of users in a wireless network.

Requests for certain publications on a web server.

The start of conflicts.

A random process is called Poisson process [

25] with the rate

if it satisfies the following definition:

For a fixed 0, we define a counting process to be Poissonian with rates when it satisfies the following:

;

the underlying increments of are independent,

within any interval having a length , the associated number of arrivals must follow a Poissonian ) distribution.

Specifically, if

provided that

serve as to be randomized independent variables satisfying

variables. Then,

This provides a simulation approach for a Poissonian process of a rate

. We start with the generated

to obtain the corresponding service times:

Additionally, must follow (11)–(12).

2.2. The Transient Queue and IL

The

queue (c., f., [

26]) is a multi-server queueing model used in queueing theory, an emerging applied probabilistic discipline, with instant service-no wait arrival, as demonstrated by

Figure 5. According to [

27,

28], the Poisson distributed service time with mean

and mean arrival rate i

in the

queueing system's transient probability is given by:

Notably, as

of Equation (16) converges to

serves as the server utilization of the underlying queue.

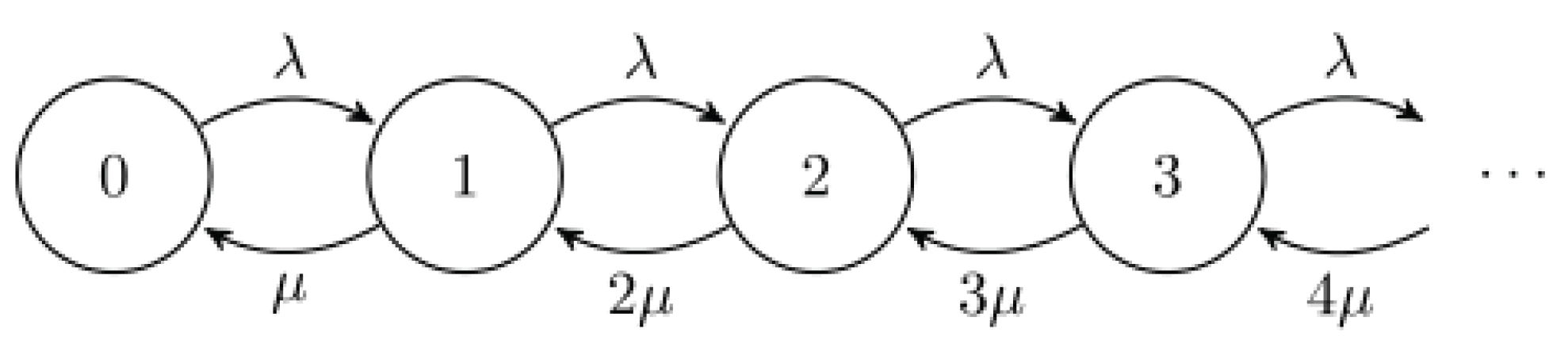

Figure 5.

The state space diagram for the chain.

Figure 5.

The state space diagram for the chain.

the information length (IL) is defined to be:

If IL of the transient queuing system, then the following theorems are devoted to the derivation of the lower and upper bounds of namely (

Theorem 1. The IL of the transient , queuing system, satisfies the following inequality:

By the definition, we have

follows. Then, we have the real number

(0,1) satisfying:

On the other hand,

, we have

In what follows, an illustration of the temporal impact as well as the potential impact of

on the behaviour of both

,

2.3. Numerical Experiments

By choosing

=

= 2, it can be easily verified that these proposed choices,

and

will read:

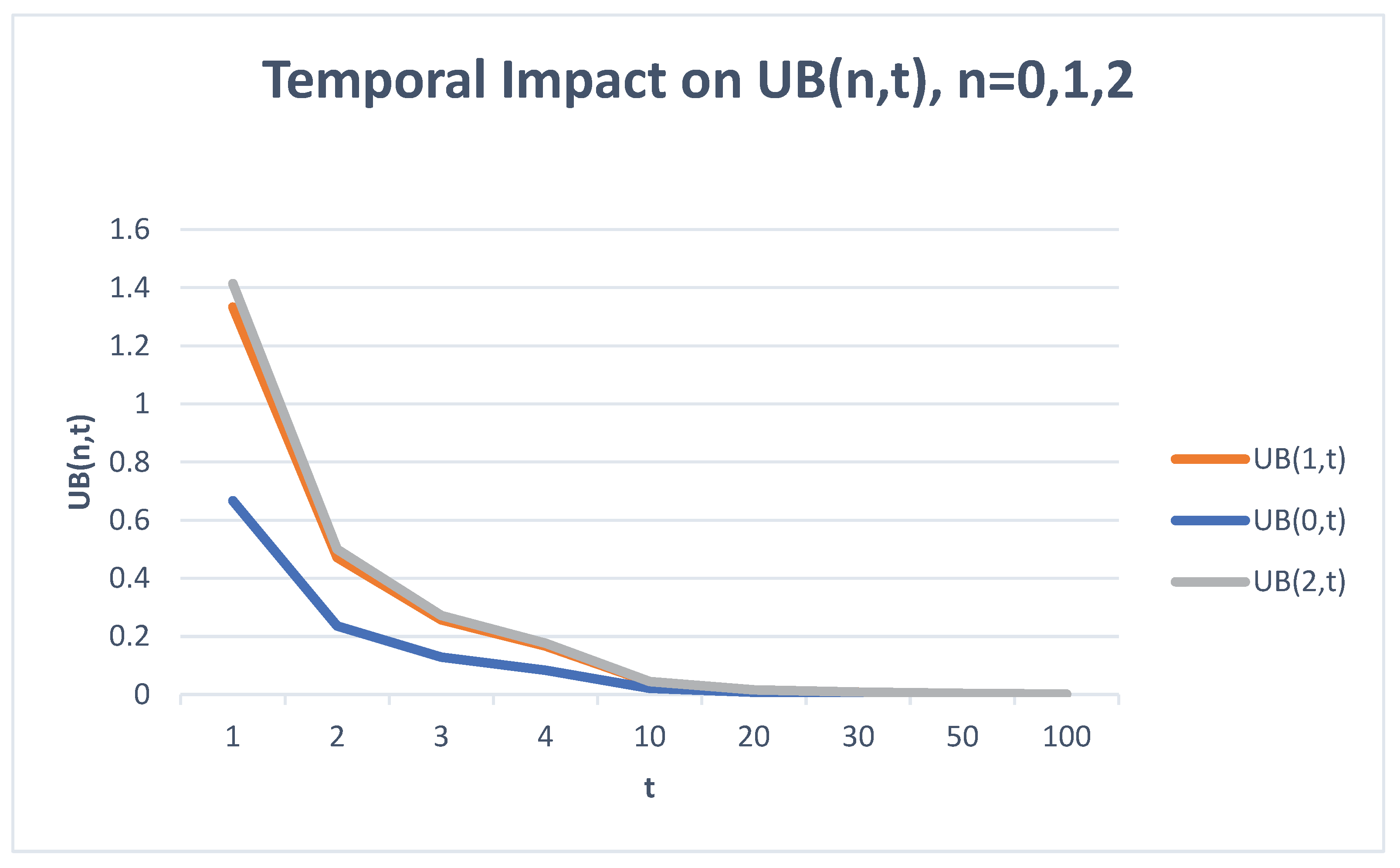

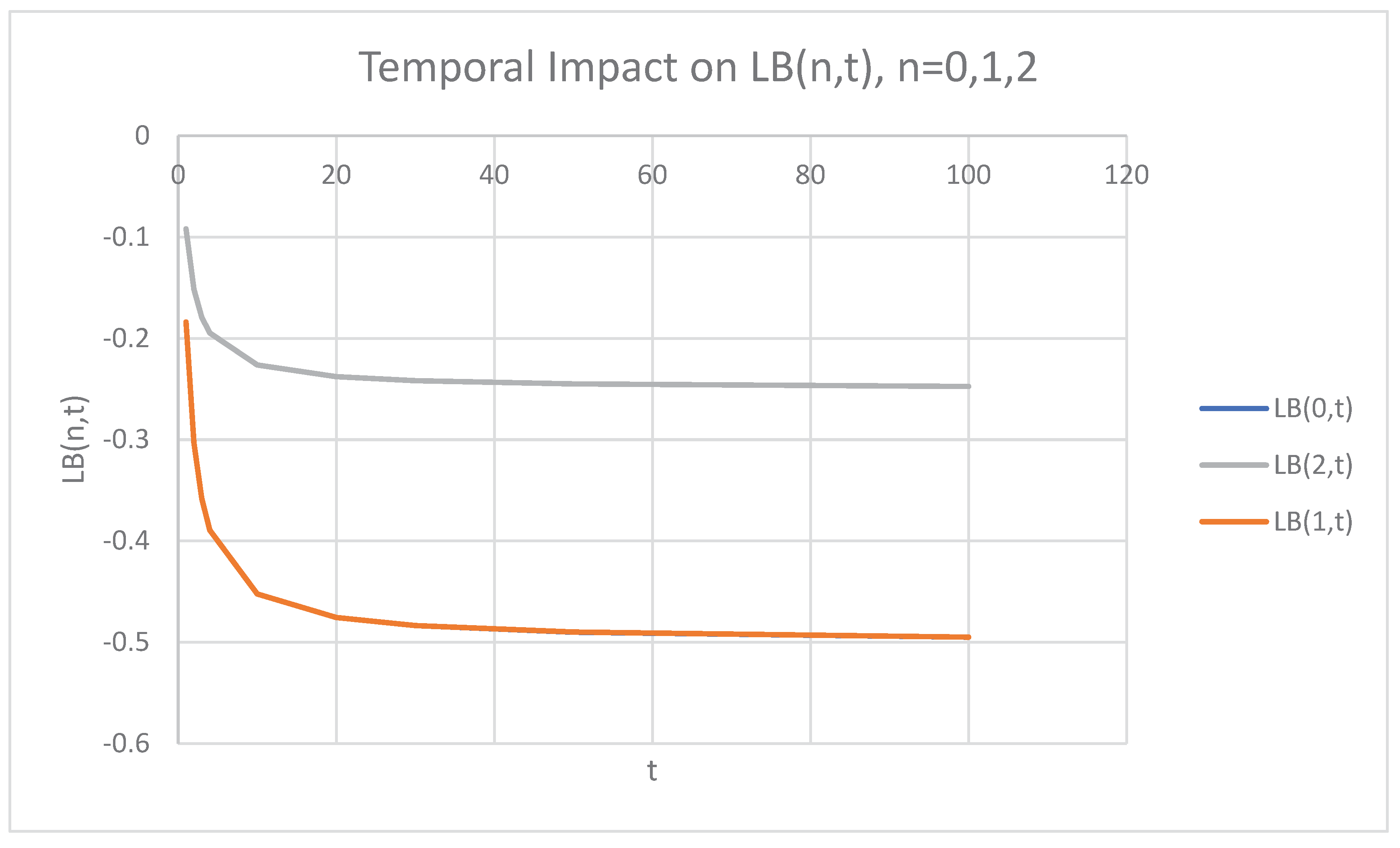

It is clear from

Figure 6, that because of the progressive increase of time,

are decreasing functions in time. Moreover, for each recorded value of time, by increasing the value of

are increasing functions. More interestingly, this reveals that

acts as decreasing function in time and an increasing function with respect to

Fundamentally, the increase of time and

impacts

to depict longer heavy tails. This translates to seeing the longest heavy tails for

, and these tails become shorter for

and the shortest would be for

.

Figure 6.

Significant Impact of time and on .

Figure 6.

Significant Impact of time and on .

Reading

Figure 7,

is decreasing in time and increasing as increases. More potentially, the graph representation of produces shorter heavy tails by the increase of time and

This shows a complete converse scenario in comparison to the recorded heavy tails phenomena in

.

Figure 7.

Significant Impact of time and on .

Figure 7.

Significant Impact of time and on .

In mathematical terms, as time becomes sufficiently large(

, it follows that

Engaging the findings of Equations (18) and (21), it holds that as time reaches infinity,

Notably, it is shown that for

transient queueing system [

27,

28] as

, the correspondent steady state probability density function,

is devised by:

Since

(c.f., (17)) does not depend on time, then we have by the definition of IL, (c.f., (2), (3)), that the corresponding stability phase of

queueing system has an underlying zero information length, that is:

Clearly, Equations (22) and (23) are equivalent. This provides a strong validation of both obtained mathematical and numerical results. The strategy of the proof can be extended to the remaining values of ., which will show that will start to decrease in both , i.e, the behavioural trend will reverse in terms of the Increasability phase in . More interestingly, it can be verified that will never change its behavioural trend in by being temporarily decreasing and increasing with the respective increase of

In a more detailed account, communicating [

30]

, it could be analytically demonstrated that and

(c.f., (20)) are both (increasing in

)(decreasing in

) by showing that:

Additionally, engaging [

31], the Stirling formula to compute

is written as

This proves (I).

Hence, (II) follows.

Fundamentally, we have demonstrated with strong supporting mathematical evidence that the undertaken experiments agree with the analytic proofs.

3. Concluding Remarks, Open Problems, and Future Research

This paper contributes to the establishment of Information Length Theory of Transient Queueing Systems. The novel mathematical derivations are undertaken by finding the integral formula of the information length of the transient queuing system. Because of the complexity to derive the closed form result of the later integral formula, both the upper and the lower bounds of that integral, namely were derived.

More interestingly, it is observed that are both (-dependent, , with to define the time-dependent server utilization of the transient queuing system. Moreover, these analytic findings were validated numerically.

Here are some emerging open problems:

Is it mathematically feasible to unlock the challenging problem of finding the exact analytic form of , (c.f., (18)), rather than obtaining its upper and lower bounds? This problem is still open.

Can we extend the undertaken approach to other transient queueing systems, such as the Parthasarathian transient?

Looking at Equation (18), can we find any other strict upper and lower bounds for ? Future research pathways include the attempting to solve the proposed open problems and extending the information data length theory to explain other fields of human knowledge, such as engineering, physics and much more.

References

- [Green, L.V. (2003). “How many hospital beds? Inquiry.”, 39: 400-412.

- Green, L.V.,et al.(2005). “ Using queueing theory to increase the effectiveness of physician staffing in the emergency department.” Academic Emergency Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Green, L.V., and Nguyen, V.(2001). “ Strategies for cutting hospital beds: The impact on patient service.” Health Services Research,36: 421-442.

- Gao, J. and K.Ozbay. (2016). “Modeling double parking impacts on urban street.” In Transportation Research Board 95th Annual Mesting. Vol 12.

- Dharmaprani, D; et al.(2021). “M/M/Infinity birth-death process- A quantitative representational framework to summarize and explain phase singularity and wavelet dynamics in atrial fibrillation.” Frontiers in physiology 11:616866. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I. A. (2023, July). Where the mighty trio meet: Information Theory (IT), Pathway Model Theory (PMT) and Queueing Theory (QT). In 39th Annual UK Performance Engineering Workshop (p. 8).

- Quah, J; et al.(2020). “Prospective cross-sectional study using Poisson renewal theory to study phase singularity formation and destruction rates in atrial fibrillation (RENEWAL-AF): Study design.” Journal of Arrhythmia 36(4):660-7. [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, HR; et al. (2020). “ Information Length Quantification and Forecasting of Power Systems Kinetic Energy.” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems.

- Mageed, I. A., Yin, X., Liu, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2023, August). ℤ(a,b) of the Stable Five-Dimensional $ M/G/1$ Queue Manifold Formalism's Info-Geometric Structure with Potential Info-Geometric Applications to Human Computer Collaborations and Digital Twins. In 2023 28th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Mageed, I. A., Zhang, Q., Akinci, T. C., Yilmaz, M., & Sidhu, M. S. (2022, October). Towards Abel Prize: The Generalized Brownian Motion Manifold's Fisher Information Matrix With Info-Geometric Applications to Energy Works. In 2022 Global Energy Conference (GEC) (pp. 379-384). IEEE.

- Mageed, I. A., Zhou, Y., Liu, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2023, August). Towards a Revolutionary Info-Geometric Control Theory with Potential Applications of Fokker Planck Kolmogorov (FPK) Equation to System Control, Modelling and Simulation. In 2023 28th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Mageed, I. A., & Kouvatsos, D. D. (2021, February). The Impact of Information Geometry on the Analysis of the Stable M/G/1 Queue Manifold. In ICORES (pp. 153-160).

-

Van Erven, T. and Harremos, P. (2014). “Rényi divergence and Kullback-Leibler divergence.” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 60(7), 3797-3820. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. "A Unified Information Data Length (IDL) Theoretic Approach to Information- Theoretic Pathway Model Queueing Theory (QT) with Rényi entropic applications to Fuzzy Logic," 2023 International Conference on Computer and Applications (ICCA), Cairo, Egypt, 2023, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1109/ICCA59364.2023.10401761.

- Kim,E. and R. Hollerbach.(2017). “Signature of nonlinear damping in geometric structure of a nonequilibrium process.” Physical Review E vol. 95, no. 2, p. 022137. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S,B. et al.(2020) “Time–information uncertainty relations in thermodynamics.” Nature Physics16.12 : 1211-1215. [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, J., and E. Kim.(2019). “Comparing information metrics for a coupled- Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process.” Entropy 21(8):775. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.(2021). “Information geometry and non-equilibrium thermodynamic relations in the over-damped stochastic processes.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment vol. 2021, no. 9, p. 093406. [CrossRef]

- Kim,E. and A.-J. Guel-Cortez. (2021). “Causal information rate.” Entropy vol. 23, no. 8, p. 1087. [CrossRef]

- Guel-Cortez, A.-J. And E. Kim. (2020). “Information length analysis of linear autonomous stochastic processes.” Entropy 22(11). [CrossRef]

- Guel-Cortez, A.-J. and E. Kim. (2021). “Information geometric theory in the prediction of abrupt changes in system dynamics.” Entropy vol. 23, no. 6, p. 694. [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, J. and E. Kim.(2016). “Novel mapping in non-equilibrium stochastic processes.”Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical vol. 49, no. 17, p. 175002. [CrossRef]

- Kim,E.(2016). “Geometric structure and geodesic in a solvable model of non-equilibrium process.” Physical Review E vol. 93, no. 6, p. 062127.Entropy vol. 20, no. 8, p. 550. [CrossRef]

- Hollerbach,R; et al.(2018). “Information geometry of nonlinear stochastic systems.” Entropy: 20(8):550. [CrossRef]

- Pishro-Nik, H. (2014). “Introduction to probability, statistics, and random processes.”, available at: https://wwww.probnabilitycourse.com, Kappa Research LLC.

- Harrison P.G. and N.M.Patel.(1992). “Performance modelling of communication networks and computer architectures.” International Computer S. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.

- Kumar, B.K; et al.(2014). “Transient and steady-state analysis of queueing systems with catastrophes and impatient customers.” Int. J. Mathematics in Operational Research Vol. 6, No. 5. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.G.(2016). “Modelling and analysis of stochastic systems.” Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Ovler, F.W; et al.(2010). “ Digital Library of Mathematical Functions.” National Institute of Standards and Technology from https://dlmf.nist.gov (release date 01-07-2011, Washington, DC. 2010).

- Guichard, D. (2017). “Single and multivariable calculus: Early transcendentals.” Available online at: https://www.whitman.edu/mathematics/multivariable/.

- Peng, J., 2020. Shape of Numbers and Calculation Formula of Stirling Numbers. Open Access Library Journal, 7(3), pp.1-11. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Parthasarathy, “A transient solution to an M /M /1 queue: A simple approach, ”Adv. Appl. Prob., vol. 19, 1987, p. 997-998. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).