1. Introduction

Nursing homes were disproportionally affected early in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic given their congregate nature and population served. Nursing home residents, often older adults with underlying chronic medical conditions, are at increased risk of severe disease, hospitalization, and death [

1]. In Switzerland, half of all COVID-19-related deaths occurred in nursing homes [

2]. The SEROCoV-WORK+ Study Group, that assessed seropositivity rates across essential workers in the canton of Geneva during the first pandemic wave, showed a strong positive association between the proportion of seropositive staff in each nursing home and the cumulative incidence of COVID-19-related cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among residents [

3]. This study also found that seroprevalence rates in nursing home staff were approximately 90-fold higher than the reported number of COVID-19 cases in nursing home staff [

2].

There is little research on the disparities in COVID-19 cases and the risk factors for infection spread in nursing homes. Previous North America-based studies have found that chronic disease and related atypical presentation of symptoms, as well as contact with infected asymptomatic direct-care workers, make nursing home residents particularly vulnerable to infection [

4]. Other predictors are facility-specific, such as staffing hours, resident-to-staff ratio and implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) [

5,

6,

7]. NPIs were at the forefront of outbreak control when vaccines and/or treatments were not available. Examples of NPIs include testing for infection, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), physical distancing, and other strategies. An epidemiological model of the effect of major NPIs across 11 European countries, including Switzerland, found that physical distancing and national lockdowns have had an effect in decreasing COVID-19 transmission [

6]. However, since most NPIs were implemented in tandem or in rapid succession with no regulation, and are largely a function of human adherence, it remains difficult to disentangle the extent of both effect sizes of each intervention.

The objective of this mixed-methods study was to assess which NPIs individual nursing homes followed for their staff and residents during the first wave of COVID-19 in the canton of Geneva, Switzerland. Canton-specific recommendations for nursing homes largely included: limited contact with visitors, social distancing where possible, increased hand hygiene, wearing facemasks in presence of residents, coughing into tissue paper or one’s elbow, or restricting access to common spaces. We also aimed to understand whether these were associated with limiting the spread of infection in the nursing home settings.

2. Materials and Methods

Nursing homes were included in this study if they were located in the Canton of Geneva and had health care workers enrolled in the aforementioned SEROCoV-WORK+ study [

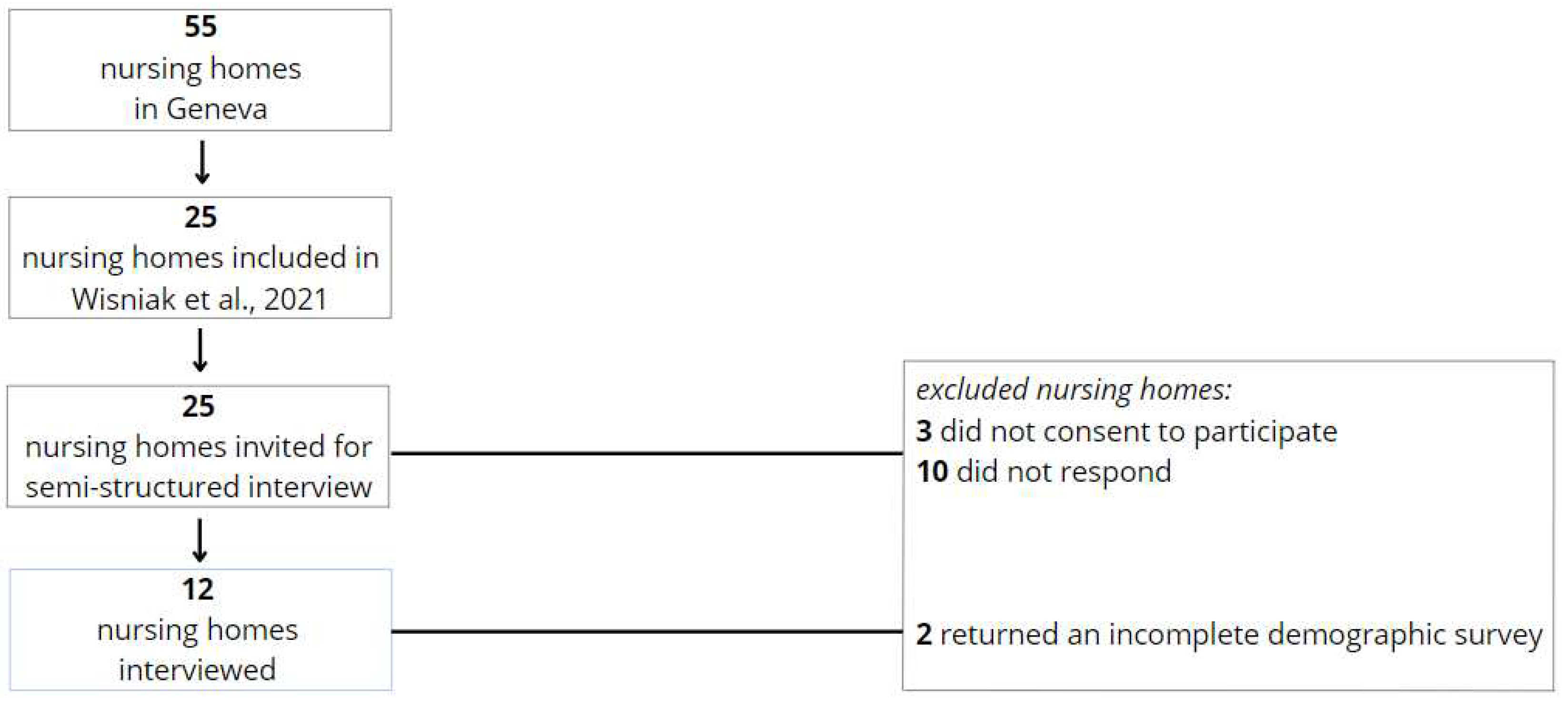

3]. Nursing homes were excluded from this study if they withdrew consent to participate in either, or both, the interview and demographic survey. Out of the eligible 25 nursing homes, our final study population consisted of 12 institutions that agreed to participate. We interviewed the attending physicians and/or director of these nursing homes to assess COVID-19 screening strategies, nursing home policies/management, and COVID-19 infection control measures to identify factors that might have affected COVID-19 spread in their nursing homes, during the first wave between March 1, 2020 and June 1, 2020. Of the 55 established nursing homes in Geneva, 25 were included in Wisniak et al., 2021. Of these, we interviewed 12, and analyzed the demographics of 10 (

Figure 1).

We designed a semi-structured questionnaire and pre-tested its psychometric properties through a rapid face validation process; we interviewed one nursing home director to explain what overarching theme they thought the questionnaire intended to measure. Formal consent of the attending physicians and directors was obtained prior to the semi-structured interviews. Nursing homes were assured that this study was only exploratory of best anti-COVID-19 practices; not a critique of the approaches individual nursing homes used. Any person-specific or institution-specific data collected were encoded and treated with utmost confidentiality.

We conducted all interviews in French, through videoconference or in person, between March 24, 2021 and May 6, 2021. Each interview lasted between 30-40 minutes. Questions retrospectively explored, (1) COVID-19 screening strategies, (2) nursing home policies/management, and (3) COVID-19 infection control measures, in each included nursing home during the first wave of COVID-19. Participants were also given a quantitative survey to complete during, or after, the interview. This questionnaire collected baseline institutional data, including size of workforce, and distribution of residents by age and/or sex. The pre-validate questionnaire and demographic survey can be found in

Appendix A and

Appendix B, respectively.

Conversations were recorded and transcribed for text mining and thematic analysis guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step framework for qualitative research (7). We exclusively used in vivo coding, where the code itself is something the participant has said. This was particularly relevant for this study because both interviewers and interviewees used phrases specific to NPIs in the nursing home context. Coding was performed manually to give full and equal attention to each NPI, and candidate themes were refined in a re-iterative process with the research team.

We also evaluated the association between the thematic classification of nursing homes with maximally, moderately, and minimally restrictive NPIs, and the cumulative incidence of PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases in the resident population. This methodology has been described in detail previously [

2]. Data on PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases among residents of nursing homes in the canton of Geneva were obtained from the Department of Security, Population and Health of the canton of Geneva for the period between March and June 2020. The association between the degree of NPIs (maximally, moderately or minimally restrictive) and the incidence of COVID-19 cases in the twelve nursing homes were assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and quasi-Poisson log-linear regression models. Results of the regression models are presented as incidence rate ratios (IRR) with their 95% confidence intervals. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using R statistical software (v. 4.0.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

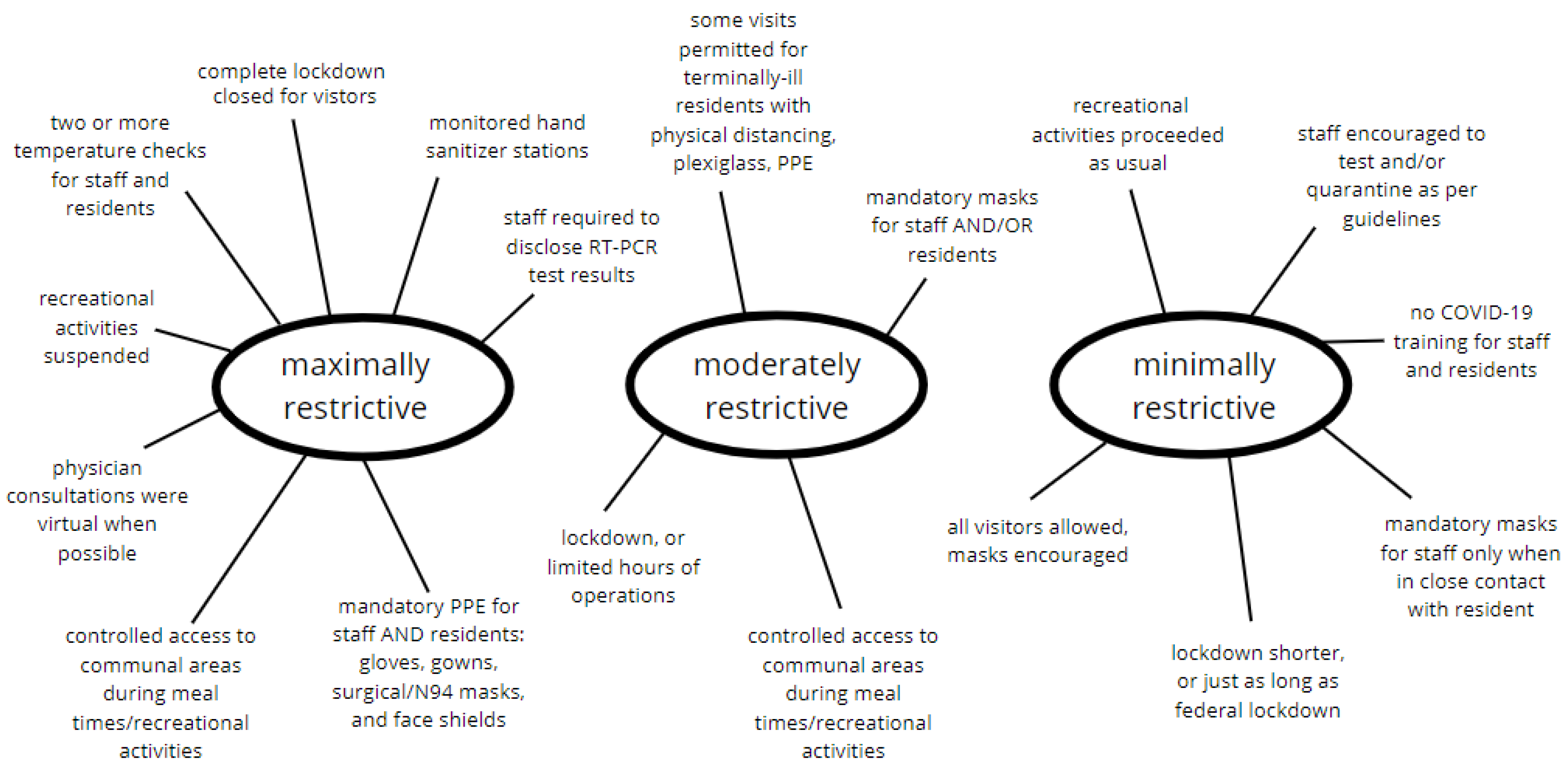

In-vivo codes formed an analytic narrative that represented three themes: maximally restrictive, moderately restrictive, and minimally restrictive (

Figure 2). NPIs in nursing homes were classified as maximally restrictive if they involved all of the following: complete lockdown, multiple daily prevention strategies (temperature check, antigen or RT-PCR test, mandatory PPE, hand hygiene), restricted access to communal areas, and entirely closed for visitations. Moderately restrictive measures included: limited operating hours for visitations, some daily prevention strategies (temperature check, obligatory mask, hand hygiene), and regulated access to communal areas. Nursing homes that generally allowed their residents and staff to autonomously adopt anti-COVID-19 measures were classified under the ‘minimally restrictive’ thematic umbrella.

Figure 1 displays the final thematic map created for this data set.

3.1. Nursing home demographics

Nine nursing homes provided baseline demographic statistics. Between March and May 2020, these institutions had an average of 74 staff present on site, including nurses, qualified and non-qualified caregivers, social workers, restaurateurs, housekeeping, therapists, volunteers, and administrative employees. Between 60-80% of these employees were female, and more commonly between 30-50 years of age. The percent of healthcare staff in these nursing homes that worked part-time hours ranged from 55% to 98%.

3.2. Screening strategies for staff, residents, and visitors

Five nursing homes stated that they had no screening methods for their nursing home workforce. The same nursing homes also stated that they had no screening methods for their residents. Other NPIs for staff included temperature checks at the reception, and obligatory mask-wearing, and hand hygiene upon entry into the facility. Three interviewees mentioned specifically that though their workforce was encouraged to self-screen, those with obvious COVID-19-compatible symptoms were referred to a general physician. It is unknown how often, or to what extent these referrals were followed through.

Screening for residents more commonly involved between one or two temperature checks each day. Two nursing homes mentioned increased awareness to COVID-19 symptoms among residents, such as “fever, digestive issues, and cough”. Eight nursing homes remained under lockdown during the first wave of COVID-19 in Geneva, each that lasted a minimum of three weeks. However, these lockdowns varied in the spectrum of maximally restrictive to not restrictive. One interviewee stated that their nursing home started a lockdown one week in advance of the federal lockdown. Another home started welcoming visitors towards the end of April; meetings happened exclusively in their cafeteria, through a plexi-glass shield. A third nursing home mentioned that they did not enforce a lockdown and allowed visitors, particularly for terminally ill residents.

3.3. Management of staff and residents who test positive and/or present symptoms compatible with COVID-19

Ten nursing homes asked their workforce to quarantine at home for at least ten days if they tested positive for COVID-19 or came into contact with someone who tested positive. Two interviewees mentioned asymptomatic employees that tested positive simply maintained a distance from residents. While one nursing home had a dedicated unit for residents that tested positive for COVID-19, all other institutions asked residents to remain in their respective rooms if symptomatic.

Since most nursing homes did not have a dedicated COVID-19 unit, residents that tested positive remained isolated in their rooms until symptoms subsided and/or an RT-PCR test returned negative. Two interviewees added that they restricted contact for symptomatic residents to two staff members, and another noted that their institution had a small team of COVID-19-trained staff. Four nursing homes stated that none of their residents tested positive for COVID-19.

3.4. Shortages of personal protective equipment

Eight nursing homes did not face any immediate shortages of PPE due to pre-existing stocks, though two interviewees admitted they were concerned with mask supplies. Four nursing homes added that they limited one mask and one gown, per staff member, per day. This meant their workforce was wearing single-use personal protective equipment for up to twelve hours a day. These shortages lasted between fifteen days and two months. During this time, one interviewee noted that their staff members only wore a mask when in direct contact with a resident.

3.5. Existing infection containment policies

Interviewees reported that all anti-COVID-19 protocols at the nursing home were within the purview of recommendations by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. Residents were provided with personal sanitizer bottles, a mask, and information brochures.

Five nursing homes did not have an existing outbreak protection plan before the COVID-19 pandemic. Other institutions relied on previous influenza outbreak plans, or general communications from cantonal health organizations. Most interviewees agreed that previous case management policies for outbreaks were effective during the first wave of the pandemic, as these were already familiar to their workforce. One nursing home stated that they complied instead with a business continuity plan and a new organizational model to avoid staff absenteeism when switching to twelve-hour schedules.

3.6. Frequency of social interactions

Four homes reported they restricted all access to communal spaces during the first wave of COVID-19; meals were eaten in resident rooms directly, and visitations and all in-person activities were suspended. Four other nursing homes controlled access to their communal spaces; residents had one socially distanced meal a day in the cafeteria, visitations took place in a dedicated space with obligatory mask wearing, and in-person activities were limited to groups of five residents. The final four nursing homes reported all dining and recreation spaces remained open, and visitors were welcome with masks and appropriate hand hygiene.

All nursing homes did not require their residents to wear masks. Instead, residents were encouraged to maintain distances of at least one meter, and sanitize hands regularly. Interviewees reasoned that they were faced with making decisions that demanded a “compromise between health security and quality of life of residents for long-term health outcomes” during the first wave of COVID-19.

3.7. COVID-19 information dissemination

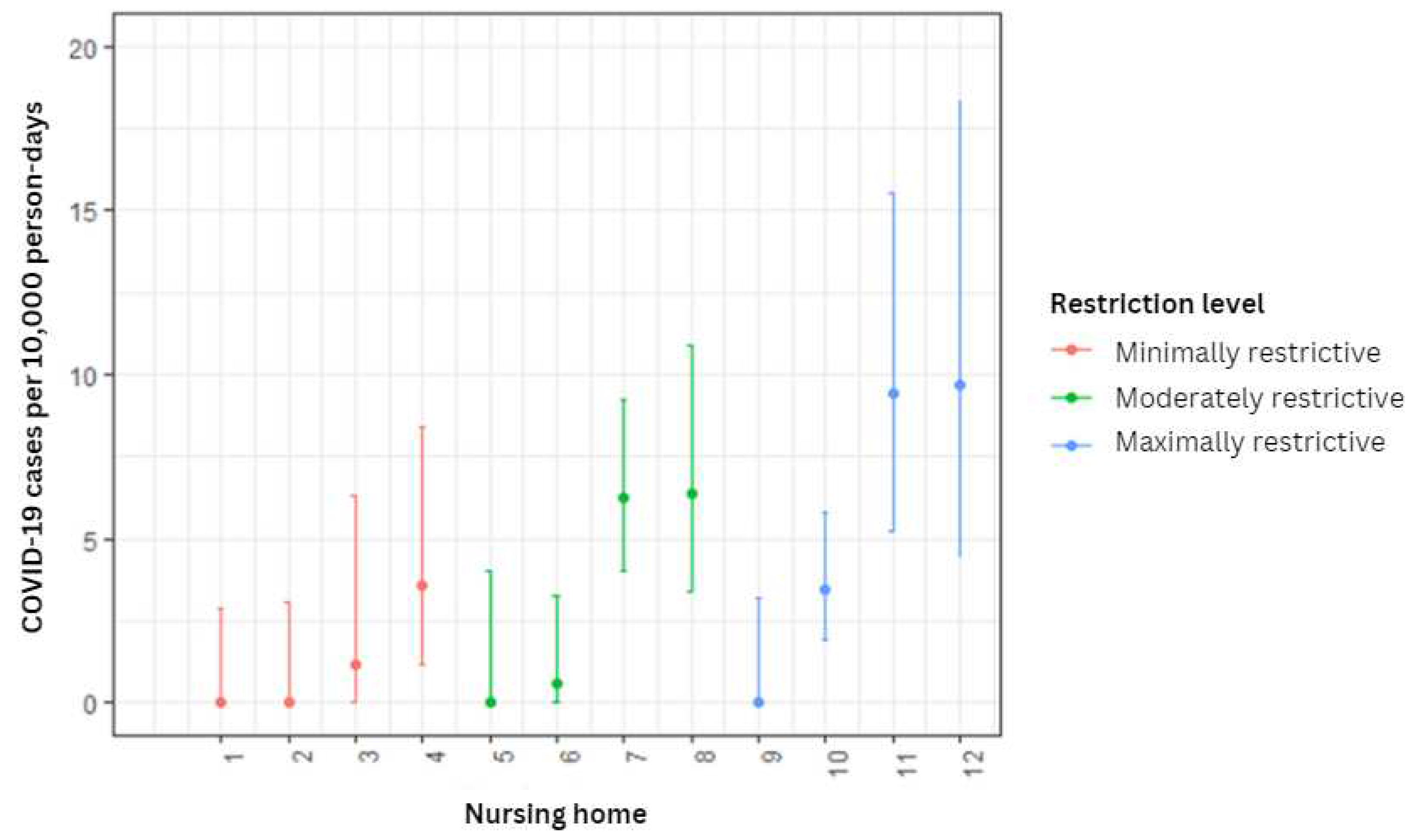

Five nursing homes arranged formal COVID-19 training and/or information sessions for their staff. Some of these workshops were led by medical personnel and covered best practices for infection control, including correct use of PPE. The same nursing homes also arranged informal discussions for thirty minutes with their residents, while another three institutions opted to distribute COVID-19 factsheets to residents and their families. Generally, “multiple communication channels were used between management, caregivers and families”, including emails, factsheets, and signage. Most nursing homes had a visit from their attending physician two times weekly, though one institution specified that these visits were sometimes virtual. All interviewees reported that their attending physicians did not participate in either formal or informal information sessions. Of the 12 nursing homes interviewed, we observed an equivalent, one-third, distribution of maximally restrictive, moderately restrictive, and minimally restrictive NPIs. To assess if these themes are associated with more or less infection, we compared the three levels of restriction and the cumulative incidence of PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases in their resident population (

Figure 3). The incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for moderately and maximally restrictive measures were estimated to be 3.55 and 3.90, respectively, when compared to minimally restrictive NPIs as reference (

Table 1). These associations were not statistically significant.

The extent of NPIs implemented (thematically categorized as maximally, moderately, or minimally restrictive) did not show to have a significant association with the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 cases among residents.

4. Discussion

Semi-structured interviews with representation from one-fifth of nursing homes in Geneva revealed that most nursing homes mandated NPIs for their staff and residents during the first wave of COVID-19. Despite comparable health policies, financing, and socio-economic standards, nursing homes in our study showed high variability in which NPIs, and to what extent, they implemented. There was an equal distribution of maximally, moderately, and minimally restrictive NPIs for COVID-19 for workers and residents between March and May 2020. This variation also appeared to persist over the three-month period, suggesting a temporal consistency; that nursing homes tended to maintain their chosen approach through the first wave of the pandemic.

While some homes imposed measures to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2, such as restrictions on visits and social activities, evidence of their effectiveness remains limited. We were unable to establish a concrete link between how restrictive NPIs in nursing homes were, and COVID-19 positivity in residents and/or staff. This is not surprising, given that the positive association between staff seroprevalence and COVID-19 cases in residents also had large variability, as did the staff seroprevalence between nursing homes [

2,

3]. This suggests that regardless of the NPIs adopted by nursing homes, other determinants of infectious disease transmission are at play. A Swiss study revealed that factors such as routine symptom screening of healthcare workers, regulation of visits, the proportion of single rooms in the facility, and isolating COVID-19 patients in single rooms are potentially protective factors [

8]. However, why some institutions were so heavily affected, while others were almost entirely spared, is not fully understood.

In our study population, 41% of nursing homes did not have formal screening methods in place for staff. We hypothesize that that residents were most likely infected by staff rather than the reverse, emphasizing the need for interventions directed at healthcare workers to mitigate COVID-19 risks in long-term care facilities. The practice of employing part-time staff across multiple long-term care institutions could contribute to the intra- and inter-facility spread of SARS-CoV-2 [

9]. International evidence also indicate that screening healthcare workers for COVID-19, even when asymptomatic, proves to be an effective preventive strategy [

10]. As a more rigorous strategy, some staff members of nursing homes in France decided to voluntarily confine themselves with their residents to reduce the risk of entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the facility [

11]. The retrospective cohort study that followed found that rates of COVID-19 cases and mortality were lower among nursing homes that implemented staff confinement with residents, compared with those derived from a population-based national survey of nursing homes.

Strict visitor regulation may decrease resident mortality, but with adverse effects on resident well-being [

12]. Furthermore, to what extent differing levels of restrictions protect residents from infection remains unclear. A Dutch guideline was developed to cautiously open nursing homes for family visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a related study reported no new cases among residents provided there was strict adherence to infection prevention and control measures [

13]. Visiting restrictions may affect patients, families, and health care services for longer than the actual pandemic. The level of global evidence on longer-term effects from visiting restrictions is low, and warrants further research [

1]. Even if the results of our study do not allow us to understand which measures are most effective in reducing transmission from health care staff to resident, they point to a larger public health discussion on maintaining a trade-off between infection control interventions that, at times, can limit positive social interactions and impact overall well-being. This approach reflects the complexity of decision-making in public health crises, and the need for nuanced and adaptive response strategies that rely on determinants other than morbidity or mortality. The scarcity of PPE exacerbates the complexities of decision-making. Interviewees highlighted a limited supply of surgical masks, with staff resorting to wearing a single mask throughout a twelve-hour shift. This scenario underscores the critical importance of implementing robust supply chain management and effective resource allocation strategies within healthcare institutions, particularly during periods of increased demand.

Our analysis is limited to the first wave of COVID-19, between March and May 2020. The retrospective design of the questionnaire is also subject to social desirability recall bias; we cannot guarantee the authenticity of answers, especially given that the nursing home physicians interviewed are liable to sanctions for negligence. We cannot definitively exclude the possibility that institutions experiencing more severe outbreaks may have concurrently implemented more stringent NPIs. This might suggest reverse causality, or a bidirectional relationship where the severity of the outbreak could influence the implementation of preventative measures. Inter- and intra- variability in nursing home operations and directives for their staff and residents render it challenging to estimate the extent of the efficacy of NPIs. We were unable to establish a concrete link, should it exist, between how restrictive NPIs in nursing homes were, and COVID-19 positivity in residents and/or staff. This is primarily due to study design and low statistical power. Inconsistencies in how nursing homes collect and report infections for their staff and residents may also influence the scope of this data.

5. Conclusions

During the first COVID-19 wave in the nursing homes in our study population, the trade-off decision revolved around finding a balance between implementing restrictive NPIs that safeguard public health but might negatively impact residents' well-being, and implementing fewer NPIs to support residents’ well-being at the risk of increasing infection spread. This suggests a recognition that there is no one-size-fits-all solution; decision-makers should continually assess the situation, considering the evolving circumstances and the best available data to find the most appropriate trade-off between health protection and the preservation of well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.K., J.-F.B., L.K.M, A.W., S.S. I.G.; Methodology and Questionnaire, L.K.M., A.W.; Validation, O.K., J.-F.B., S.R.; Interviews, O.K., J.-F.B; Analysis, L.K.M., A.W; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.K.M., Writing—Review & Editing, all authors; Supervision, O.K., J.-F.B., S.S., I.G.; Project Administration, O.K., S.S., I.G.; Funding Acquisition, O.K., I.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The SEROCoV-WORK+ study protocol was approved by the Cantonal Research Ethics Commission (CCER) of Geneva, Switzerland (project number 2020-00881). The protocol for the use of nursing home data from the canton of Geneva was submitted to the CCER of Geneva, and did not require approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all nursing homes prior to the semi-structured interview. Data obtained from the Canton of Geneva was in aggregated form and did not require individual consent.

Data Availability Statement

Study data that underlie the results reported in this article can be made available to the scientific community after deidentification of individual nursing homes and participants, and upon submission of a data request application to the investigator board via the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the nursing home facilities and staff that participated in this study and enabled this research to be possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview

Nursing Home:

Name and Position of Nursing Home Representative:

Date of Completion:

SECTION 1: Screening Strategies

During the first wave of COVID-19, between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020, did you implement local screening strategies (e.g., temperature measurement, RT-PCR testing)? If yes, please specify what was implemented,

for staff?

for residents?

for visitors?

- 2.

How did you manage employees with a positive test or close contact with a positive case?

- 3.

How did you handle employees that presented symptoms consistent with COVID-19?

- 4.

How did you manage residents with a COVID-19-positive test result?

- 5.

Between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020, how did you manage residents that presented symptoms consistent with COVID-19? (e.g., isolation, hospitalization, protective equipment for caregivers)

SECTION 2: The Facility

Did you experience a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the first wave, between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020? If yes, please provide details:

What type of PPE was lacking (e.g., surgical masks, N95 masks, gowns, face shields, safety goggles, hand sanitizer, gloves)?

How long did the shortage last?

How did you manage this shortage?

What PPE was eventually provided, and when?

SECTION 3: COVID-19 Preventive Measures Implemented in the Nursing Home between March 2020 and June 2020

Did you have an epidemic protection plan for the nursing home before this outbreak? If yes, did this plan serve for the COVID-19 pandemic?

Did you restrict access to certain common areas?

Were in-person activities suspended? If yes, which ones were suspended, and which continued?

Did you implement social distancing measures among residents?

How did you ensure hand hygiene for staff in your facility (e.g., hand sanitizer dispensers in common areas, posters, training)?

How did you ensure hand hygiene for residents in your facility (e.g., hand sanitizer dispensers in rooms, posters, informational sessions)?

Did you have a mask-wearing protocol between March 1, 2020 and June 1, 2020? If yes, when and how was it implemented (e.g., for employees, residents, visitors)?

Did you ban/restrict visits? If yes, when and how (e.g., restricted visiting hours, limited number of visitors, physical contact allowed)?

Did you receive instructions from your nursing home association and/or the Department of Health or the cantonal physician regarding preventive measures against COVID-19? If yes, were you able to follow them?

Did you take other measures to limit contact between residents and between caregiving staff and residents (e.g., assigning specific staff to specific residents, resident groups, or areas within the nursing home)?

Did employees receive training on COVID-19 prevention measures? If yes, when, in what format, and was it mandatory or optional?

Did physicians undergo training for COVID-19? If yes, when, in what format, and was it mandatory or optional?

Did residents have the opportunity to participate in information sessions about COVID-19 (hygiene measures and social distancing)? If yes, when, in what format, and was it mandatory or optional?

In your opinion, what were the strengths and weaknesses of your nursing home in managing the COVID-19 health crisis?

Are you a part of a nursing home association or umbrella organization?

Appendix B. Demographic Survey

Nursing Home:

Name and Position of Nursing Home Representative:

Date of Completion:

SECTION 1: Nursing Home Staff

How many people were present on-site in your facility between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020 (including temporary staff)?

Physicians:

Registered Nurses:

Nursing Assistants, Health and Community Care Assistants:

Other Caregivers:

Social Workers:

Socio-hotel Staff (meals, maintenance, etc.):

Volunteers:

Activity Team:

Chaplain:

- 2.

What percentage of healthcare staff work part-time?

- 3.

How many *caregivers worked in your nursing home between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020?

March:

April:

May:

*This includes all nurses, nursing assistants, and community care assistants, and other general caregivers. This will help us calculate the resident-to-caregiver ratio during this period.

- 4.

What is the age distribution of all employees?

- 5.

What is the gender distribution of all employees?

SECTION 2: Physicians

SECTION 3: Residents

What is the age distribution of residents?

What is the gender distribution of residents?

What was the number of beds and the occupancy rate per month between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020?

March:

April:

May:

Did you prohibit visits from family/relatives during the period from March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2020? If yes, between which dates?

SECTION 4: The Facility

References

- Jordan, R.E.; Adab, P.; Cheng, K.K. Covid-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ 2020, 26, m1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniak, A.; Menon, L.K.; Dumont, R.; Pullen, N.; Regard, S.; Dubos, R.; et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence in Nursing Home Staff and Resident COVID-19 Cases and Mortality: A Cross-Sectional Study. Viruses 2021, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringhini, S.; Zaballa, M.E.; Pullen, N.; de Mestral, C.; Perez-Saez, J.; Dumont, R.; et al. Large variation in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence among essential workers in Geneva, Switzerland. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, L.; Zisberg, A.; Cohn-Schwartz, E.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Perel-Levin, S.; Bar-Asher Siegal, E. Long-term care settings in the times of COVID-19: challenges and future directions. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1239–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adil, M.T.; Rahman, R.; Whitelaw, D.; Jain, V.; Al-Taan, O.; Rashid, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and the pandemic of COVID-19. Postgrad Med J. 2021, 97, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaxman, S.; Mishra, S.; Gandy, A.; Unwin, H.J.T.; Mellan, T.A.; Coupland, H.; et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature 2020, 584, 257–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanferla, G.; Héquet, D.; Graf, N.; Münzer, T.; Kessler, S.; Kohler, P.; et al. COVID-19 burden and influencing factors in Swiss long-term-care facilities: a cross-sectional analysis of a multicentre observational cohort. Swiss Med Wkly. 2023, 153, 40052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, T.M.; Clark, S.; Pogosjans, S.; Kay, M.; Lewis, J.; Baer, A.; et al. COVID-19 in a Long-Term Care Facility — King County, Washington, February 27–March 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 339–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykgraaf, S.H.; Matenge, S.; Desborough, J.; Sturgiss, E.; Dut, G.; Roberts, L.; et al. Protecting Nursing Homes and Long-Term Care Facilities From COVID-19: A Rapid Review of International Evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021, 22, 1969–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmin, J.; Um-Din, N.; Donadio, C.; Magri, M.; Nghiem, Q.D.; Oquendo, B.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outcomes in French Nursing Homes That Implemented Staff Confinement With Residents. JAMA Netw Open. 2020, 3, e2017533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugelius, K.; Harada, N.; Marutani, M. Consequences of visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021, 121, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeek, H.; Gerritsen, D.L.; Backhaus, R.; De Boer, B.S.; Koopmans, R.T.C.M.; Hamers, J.P.H. Allowing Visitors Back in the Nursing Home During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Dutch National Study Into First Experiences and Impact on Well-Being. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020, 21, 900–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).