1. Introduction

Occupational pension is a crucial labor protection system in many countries. In 1984, China introduced an enterprise pension system to partially provide retirement benefits to enterprise workers (Zheng, Lyu, Jia, Hanewald, & Finance, 2023). The occupational pension system became mandatory nationwide in 2011 with the introduction of the Social Security Law in 2010 (Shan & Park, 2023). Under the Social Security Law, both employers and employees are responsible for paying basic occupational pension premiums (H. Wang, Huang, & policy, 2023). As society grows, pension premiums continue to increase, so the cost to the business continues to rise (J. Hu, Stauvermann, Nepal, Zhou, & Health, 2023; H. Wang et al., 2023; Jin Wang, Wang, Long, & Chen, 2023). These cost shocks costs have affected enterprise behavior and investment decisions in various ways, such as increasing tax avoidance (Campbell, Goldman, & Li, 2021), reducing outward investment (Duckett & Change, 2020), inhibiting innovation (W. Gao, Chen, Xu, Lyulyov, & Pimonenko, 2023), and influencing strategic corporate decisions (Agarwal, Pan, & Qian, 2020; Wahyudi, Hasanudin, & Pangestutia, 2020).

Will firms cut or maintain their corporate social responsibility (CSR) investments amid rising pension premiums? Theoretical analyses of the possible mechanisms involved still leave the answer uncertain. CSR refers to the activities of enterprises that incorporate social and environmental issues into their operations and interactions with stakeholders (Van Marrewijk, 2003). According to Porter and Kramer’s (2006) framework for CSR decision-making, CSR can be divided into two categories: responsive and strategic (M. E. Porter & M. R. J. H. b. r. Kramer, 2006). Responsive CSR aims to improve short-term stakeholder relationships and is often viewed as a symbolic impression management activity (Michael E. Porter & Mark R. Kramer, 2006), or short-term investment separate from the organization’s core business (Bansal, Jiang, & Jung, 2015; Muller & Kräussl, 2011). Strategic CSR is an investment with limited short-term returns and requires long-term planning, significant resource investment, and major organizational restructuring (Bansal et al., 2015; Habib & Hasan, 2016; Kang, 2016).

When firms face cost shocks, they must weigh the costs of adjusting CSR, including economic losses (Ibrahim, Ali, Aboelkheir, & Taxation, 2022) and social, contractual, or psychological costs (Costa & Habib, 2023), as well as the loss of intangible assets such as reputational capital (Ibrahim et al., 2022). This understanding is based on cost stickiness theory (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Venieris, Naoum, & Vlismas, 2015). Cost-stickiness theory suggests that certain costs are sticky and increase more with a firm’s business volume rather than decrease when business volume falls asymmetrically (Anderson, Banker, & Janakiraman, 2003; Venieris et al., 2015). Several studies have shown that CSR is a long-term investment with limited short-term returns (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Kang, 2016). The value-creating effect of CSR can only be realized through sustained investment (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Kang, 2016). If firms respond to the labor cost shock of rising occupational pension costs by reducing CSR expenses or adjusting CSR inputs, they will also face higher adjustment costs, which may force them to abandon CSR altogether (Habib & Hasan, 2016; Venieris et al., 2015).

Besides exploring the mechanisms of firms’ adjustment to CSR based on the cost stickiness theory, this study introduces the resource base theory to illustrate how CSR affects organizational resilience. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, organizational resilience has emerged as a critical factor in ensuring sustainable business operations, environmental adaptability, and quality development (Kantur & Say, 2015). The level of organizational resilience indicates how well firms cope with and adapt to turbulent environments (Guo, Kuai, & Liu, 2020; Jiang, Ritchie, & Verreynne, 2019). However, few studies have analyzed the impact of CSR from the perspective of organizational resilience (Torres & Augusto, 2021). Resource-based theory was first proposed by Wernerfelt (1984), who argued that scarce resources acquired by firms can help them improve their competitiveness and performance (Wernerfelt, 1984). Studies have shown that corporate investment in social responsibility leads to more effective advice and greater acquisition of scarce resources for stakeholders (Freeman, Dmytriyev, & Phillips, 2021). This study applied resource-based theory to analyze the impact of CSR on organizational resilience from the perspective of resource acquisition as well as applying insights drawn from stakeholder theory and signaling theory in the analysis.

Additionally, we assessed the moderating role of the macro-social development level. According to China’s fifth national census (2000), the proportion of the population aged 65 years and above at that time was approximately 7%, making China an aging country (Bai & Lei, 2020). As the number and proportion of the aging population increase, the dwindling labor supply poses a long-term threat to business development (Clemens, 2021; Jarzebski et al., 2021). Similar to occupational pension, the minimum wage system plays a role in safeguarding the basic living standards of those on low incomes and in improving income distribution. However, a significant increase in the minimum wage can also result in a labor cost shock (Clemens, 2021).

The moderating role of a firm’s strategic level was also assessed. Digital transformation is driving Chinese enterprises to upgrade to artificial intelligence and informatization, which is likely to significantly improve productivity through the efficient transmission of information and optimal allocation of resources (H. Li, Yang, Jin, & Wang, 2023). This study considered marketing capability as an important indicator for improving enterprise efficiency in acquiring resources (Mishra & Modi, 2016).

Current research has focused primarily on the positive effects of occupational pension on society and the labor force, while neglecting its cost to firms. Our empirical investigation, which involved Chinese A-share listed firms from 2010 to 2023, aimed to reveal the relationship between occupational pension, CSR, and organizational resilience. The findings of this study are intended to aid policymakers in comprehending and evaluating the extent of the impact of the occupational pension system in China. Additionally, they can help inform corporate managers in relation to more effective strategic decision-making when faced with labor cost shocks.

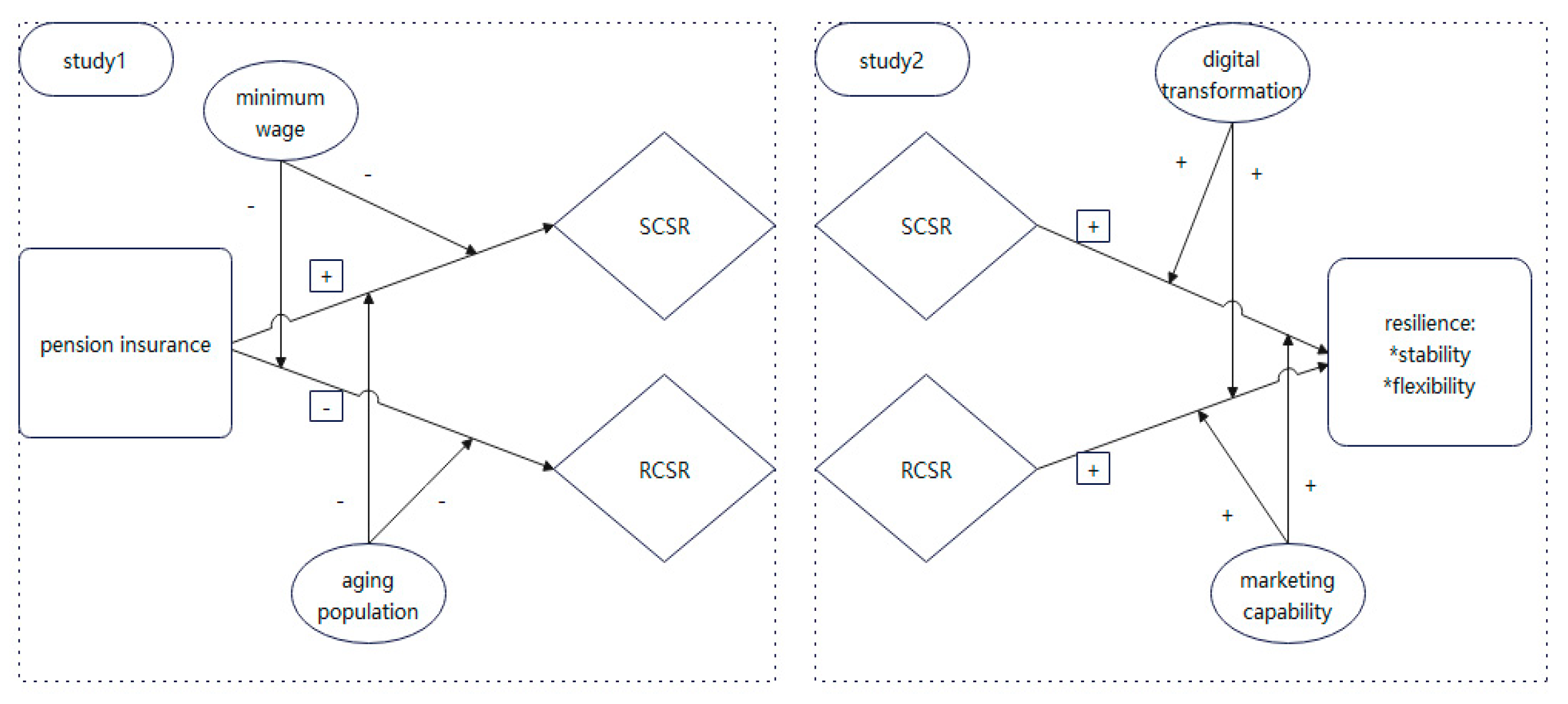

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical framework of the study.

Description: Study 1 shows that occupational pension increased strategic CSR and decreased responsive CSR. Study 2 showed that strategic and responsive CSR increased organizational resilience.

2. Theory and hypothesis development

2.1. Occupational pension, strategic and responsive CSR

There is a significant contrast between strategic and responsive CSR strategies in terms of cost stickiness (Habib, Hasan, & Research, 2016). Strategic CSR integrates social responsibility with corporate strategies, resources, capabilities, processes, business models, and stakeholder interactions (M. E. Porter & M. R. J. H. b. r. Kramer, 2006). This approach requires long-term planning, significant investments in resources, and major organizational restructuring, particularly in areas such as product and customer responsibilities (Bansal et al., 2015). Therefore, the cost of maintaining strategic CSR activities is significant. Consequently, cutting strategic CSR in response to labor cost shocks from pension premiums can lead to economic losses, social costs, contractual or psychological costs, and losses of intangible assets, such as reputational capital (Y. Chen, Guiping, & Gao, 2023; Habib & Hasan, 2016; Venieris et al., 2015).

Responsive CSR aims to improve stakeholder relations and meet stakeholder demands in the short term, aligned with established norms, expectations, and practices to build legitimacy and gain resource support (M. E. Porter & M. R. J. H. b. r. Kramer, 2006). Some have viewed responsive CSR as a token impression management activity or a short-term investment separate from the organization’s core business (Bansal et al., 2015; Muller & Kräussl, 2011). In China, responsive CSR includes exercising community responsibility through charitable donations and environmental responsibility through environmental protection inputs (Tao & Song, 2020). According to the over-investment hypothesis of agency theory, charitable giving may be viewed as agency behavior that reflects management self-interest. CEOs may be inclined to over-invest in charitable giving, which can negatively affect the interests of shareholders and the overall value of the firm. This over-investment can even become a significant economic burden, constraining firm growth (Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Friedman, 1970). Responsive CSR is a reversible short-term investment that requires fewer resources, incurs lower adjustment costs, and is less susceptible to stickiness. Therefore, we argue that firms can quickly adjust or reduce responsive CSRs when faced with labor cost shocks from pensions (Buslei, Geyer, & Haan, 2023; Jin Wang et al., 2023).

Based on the above analysis, we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Due to high cost stickiness, firms will maintain strategic CSR when facing labor cost shocks from occupational pension.

Hypothesis 1b: Due to low cost stickiness, firms will cut responsive CSR when facing labor cost shocks from occupational pension.

2.2. Strategic, responsive CSR and organizational resilience

Meyer (1982) coined the term ‘organizational resilience’ to describe an organization’s ability to respond to disturbances and restore the previous order (Meyer, 1982). Scholars have summarized the concept of organizational resilience in terms of ability or process. Organizational resilience refers to the dynamic and flexible ability of an organization to combine prediction, stability maintenance, survival, endurance, adaptation, learning, and developmental abilities (Carvalho & Areal, 2016; Ma, Su, Wang, Qiu, & Guo, 2018).

Previous studies have shown the complexity of the factors that influence organizational resilience (Andersson, Cäker, Tengblad, & Wickelgren, 2019). This study primarily examined the mechanisms of organizational resilience from three perspectives: individual, organizational, and environmental. Individual factors influencing resilience include knowledge acquisition, skill training, and ability improvement (Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd, & Zhao, 2017). In addition, creativity (Manfield & Newey, 2017), employee psychological capital (Linnenluecke, 2017), and leadership (de Oliveira Teixeira & Werther Jr, 2013) are important factors. At the organizational level, the factors with the greatest influence include managing organizational relationships (Kahn et al., 2018) and transferring information within an organization (Bustinza, Vendrell-Herrero, Perez-Arostegui, & Parry, 2019). According to Kahn et al. (2018), based on intergroup relationship theory, when a department is under external pressure, neighboring departments may use approaches such as assistance, adaptation, and integration to enhance the resilience of the department (Y. Gao & Gao, 2023; Jin, Zhang, Ye, Yao, & Song, 2024; G. Liu, Liu, Zhang, Zhu, & Organization, 2021).

Effective communication and engagement with stakeholders can improve a firm’s ability to adapt to environmental changes and reduce negative impacts (M. DesJardine, P. Bansal, & Y. Yang, 2019a; Kahn et al., 2018). By improving communication and contact with stakeholders, firms that actively engage in social responsibility activities can enhance their ability to adapt to environmental changes and reduce negative impacts caused by such changes (M. DesJardine et al., 2019a). However, few studies have examined the factors influencing firms’ organizational resilience during crises, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, in the Chinese context, it is necessary to enhance the exploration of socially responsible investments to improve organizational resilience (Lu, Yang, & Yu, 2022; M. Sajko, C. Boone, & T. Buyl, 2021a).

2.2.1. The impact of strategic CSR on organizational resilience

Strategic CSR focuses on stakeholders, such as employees, consumers, and suppliers, who are closely linked to a firm’s development, competition, and strategic changes (Pollman, 2019). For example, employee responsibility can foster loyalty, solidarity, and a positive corporate culture, which can help firms withstand shocks and overcome challenges (Crane & Matten, 2020; Fukuda & Ouchida, 2020; Pollman, 2019). By fulfilling product and consumer responsibilities, firms can develop high-quality products, build an excellent brand image, maintain and attract high-quality customers, and enhance their overall social image (Huang, Chen, & Nguyen, 2020; Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006).

According to resource-based theory, firms can improve their competitiveness and prevent crises by integrating resources (Yang, Wang, Jing, Liu, & Niu, 2022). Following understandings derived from resource-based theory and stakeholder theory, firms can effectively strengthen the connection between themselves and strategic stakeholders such as employees, consumers, and suppliers by enhancing their strategic CSR, which will enable them to acquire scarce strategic resources more readily (Yang et al., 2022). Specifically, investing in CSR strengthens the connections between firms and strategic stakeholders, which will enable such firms to obtain scarce resources that are closely related to their core business, thus strengthening their defensive capabilities in the face of crises and enhancing their stability and flexibility (M. DesJardine et al., 2019a; Sajko et al., 2021a; Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2022).

The transmission mechanism of market signals was severely comprised during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to increased information asymmetry and opacity (S. Li, Wang, Filieri, & Zhu, 2022; Polyzos, Fotiadis, & Samitas, 2021). According to signaling theory, firms can use CSR investments to communicate their stable and positive states to stakeholders, which is likely to increase stakeholder support and investment confidence in such firms, as well as enhance firms’ ability to withstand changes in the external environment (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003; M. R. DesJardine, Marti, & Durand, 2021; Fama, 1980; S. Li et al., 2022; Polyzos et al., 2021). Following understandings derived from signal and stakeholder theories, firms can release strategic CSR-related information to dispel stakeholder doubts and strengthen connections among employees, consumers, suppliers, and other stakeholders (M. R. DesJardine et al., 2021; S. Li et al., 2022).

Based on the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: Strategic CSR improves organizational resilience.

2.2.2. The impact of responsive CSR on organizational resilience

According to stakeholder theory, governments and communities are important for CSR as responsive stakeholders (Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006). Exercising environmental responsibility is mandatory in China (Elhendy, Tsutsui, O’Leary, Xie, & Porter, 2006; Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006). However, this has not been consistently applied in relation to enterprises’ core business and strategic objectives because environmental responsibility has a shorter investment cycle and is more reversible than strategic CSR (Elhendy et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2020; Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006). Community responsibility refers to the responsibilities and tasks that enterprises should undertake to maintain public safety and to help realize the public interests of community residents (Jianjun Zhang, Marquis, & Qiao, 2016). In China, autonomous organizations such as neighborhood and village committees are the main bodies that guarantee community safety and deal with emergency affairs. Community responsibility is mostly guaranteed and implemented through meeting state-enforced obligations, whereas enterprises invest in community responsibility to respond to policies and systems and meet legitimacy needs (Jianjun Zhang et al., 2016). However, investment in community responsibility requires a focus away from the core business of enterprises and does not enhance their operational capacity, improve their performance level, or help them recover (Al-Mamun & Seamer, 2021; Jianjun Zhang et al., 2016). Based on understandings derived from resource-based and stakeholder theories, responsive CSR can meet the needs of responsive stakeholders, such as the government and community, but it is difficult to obtain scarce resources related to the core business of enterprises from the government and community. Therefore, allocating resources to exercise responsive CSR may be considered wasteful, and over-investment in this area may hinder business recovery in the post-pandemic era (M. DesJardine et al., 2019a; Sajko et al., 2021a; Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2022).

According to signaling theory, responsive CSR satisfies the needs of responsive stakeholders, such as governments and communities; improves information transparency between governments, communities, and firms; and, to some extent, strengthens government and community support for firms (C.-D. Chen, Su, & Chen, 2022). However, government and community support for firms tends to emerge only after a long period of time. For example, it takes considerable time for supportive policies to be introduced. In addition, policies introduced by the government have a strong macro-regulatory function, making it difficult to influence the internal structure and resource allocation of firms (Ketter, 2022; Sharma, Thomas, & Paul, 2021; Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2022). In summary, responsive CSR makes it difficult to effectively promote firms’ organizational resilience and even impede it. Therefore, this study argues that responsive CSR does not enhance and can even undermine a firm’s organizational resilience.

Based on the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2b: Responsive CSR weakens organizational resilience.

2.3. The moderating role of minimum wage

Increases in the minimum wage create an incentive effect according to efficiency wage theory, which postulates a positive relationship between a worker’s income and his or her efficiency, and that higher wages increase productivity due to increased effort at work and motivation (especially for low-skilled workers) to upgrade and train (Clemens, 2021; Kong, Wang, & Zhang, 2020; Starr, 2019). However, minimum wages trigger negative effects when the increases exceed certain thresholds (Akee, Zhao, & Zhao, 2019; Fieseler, Bucher, & Hoffmann, 2019; Pancieri et al., 2022). According to the relevant provisions of the Labor Contract Law, firms are required to pay compensation for the dismissal of employees, the amount of which is directly linked to the minimum wage standard (Akee et al., 2019). Minimum wages reduce the cost of employee advocacy, increase the cost of dismissal, and increase job stability. Firms cannot easily fire even poorly performing employees, which dampens the motivation of others (Akee et al., 2019; Cooper, Gong, & Yan, 2018). Firms cannot easily fire employees, even poorly performing employees, which reduces the motivation of other employees (Q. Li, Zhao, Chen, & Trade, 2023). To some extent, the minimum wage increases firms’ cost burden.

Based on the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3a: Higher minimum-wage levels exacerbate decreases in responsive CSR related to occupational pension.

Hypothesis 3b: Higher minimum-wage levels mitigate increases in strategic CSR related to occupational pension.

2.4. The moderating role of population aging

The impact of population ageing on the world economy has been thoroughly analyzed in the existing literature (Nadkarni & Prügl, 2021). However, in contrast, the process of population ageing in China is complex. This is because population ageing in China is taking place in the context of “ageing before wealth” (JQ Zhang & He, 2022). Economic growth has been crucial in strengthening resources for old age, but China is now facing downward pressure on its economy (JQ Zhang & He, 2022). With its population aging faster than middle-income countries can normally sustain, China’s per capita income level has yet to reach the world’s high level (Ren, Hu, Tang, & Chadee, 2023). The challenge is how to provide the country with resources for old age (Ren et al., 2023). Population aging disrupts China’s labor market and increases recruitment costs for companies (Ding & Ran, 2021; Maestas, Mullen, & Powell, 2023). At the same time, the aging population also increases the cost of pension contributions, thus significantly increasing the operating costs of enterprises (Ding & Ran, 2021; Maestas et al., 2023).

Based on the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4a: Higher population-aging levels exacerbate decreases in responsive CSR related to occupational pension.

Hypothesis 4b: Higher population-aging levels mitigate increases in strategic CSR related to occupational pension.

2.5. The moderating role of digital transformation

The digital economy has generated new business models in areas such as the Internet (Russell, 2013), big data (Watts & Feltus, 2017), cloud computing (Wu, Pellegrini, Gao, Casale, & Systems, 2019), artificial intelligence (Barta, Görcsi, & Research, 2021), and the Internet of Things (IoT) (Y. d. Gao et al., 2021). These technologies have become increasingly integrated into various sectors of the economy and society, playing an important role in creating employment, stimulating consumption, and driving investment (Pandey & Pal, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the importance of network effects and new business models in the digital economy, which has attracted widespread academic attention (Pandey & Pal, 2020). The impact of digital transformation extends beyond macroeconomic and production spheres, with significant effects on firms’ internal and external environments, providing a strong impetus for high-quality development, transformation, and upgrading (Watts & Feltus, 2017; Wei et al., 2019). Digitally transformed firms have fewer barriers to information transfer (Lanzolla et al., 2020; Moi, Cabiddu, & Governance, 2021). In addition, digital transformation makes it easier for firms to fully absorb resources (S. Chen, Zhang, & Finance, 2021; Feyen, Frost, Gambacorta, Natarajan, & Saal, 2021).

Based on the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5a: Digital transformation mitigates decreases in responsive CSR related to occupational pension.

Hypothesis 5b: Digital transformation exacerbates increases in strategic CSR related to occupational pension.

2.6. The moderating role of marketing capability

Marketing capabilities can play a moderating role in terms of facilitating transformation of a firm’s resources into products (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Specifically, the impact of marketing capabilities on firm resilience can be categorized into two aspects. First, based on signaling and stakeholder theories, high marketing capability provides more convenient signaling channels for firms, which improves the efficiency of information transmission (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Therefore, enterprises with high marketing capabilities can appropriately signal social responsibility to stakeholders (Mishra & Modi, 2016).

Second, based on resource base theory and stakeholder theory, marketing capability refers to a firm’s ability to understand the preferences and needs of stakeholders, such as employees, consumers, products, communities, and the environment. A high marketing capability can increase the efficiency of resource transformation (Xiong & Bharadwaj, 2013). CSR investment enables firms to obtain scarce resources, and firms with high marketing capabilities can increase the effectiveness of socially responsible investments. Marketing capabilities enhance the impact of CSR and make it easier for firms to transform socially responsible resources into output and value, thereby increasing their resilience to risks (Mishra & Modi, 2016; Morgan, 2012).

In summary, this study argues that marketing capabilities facilitate the transformation of strategic CSR investments into organizational resilience by improving the efficiency of information and resource transformation. Although responsive CSR focuses on stakeholders not involved with a firm’s core business, marketing capabilities allow for this to some extent by improving the efficiency of information and resource transformations. Thus, marketing capabilities mitigate the damaging or inhibiting effects of responsive CSR on organizational resilience.

Based on the above analysis, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6a: Marketing capability promotes the transformation of strategic CSR into organizational resilience in firms.

Hypothesis 6b: Marketing capability mitigates the inhibitory effect of responsive CSR on organizational resilience in firms.

3. Methodology

Our main study is divided into two parts: study 1 examines the effect of occupational pension on CSR, and study 2 examines the effect of CSR on organizational resilience.

3.1. Sample

Our sample consists of data from 2010 to 2023 for a sample of listed companies in China. The final sample consists of 34,145 observations. All continuous variables were logged in this study. To minimize the effect of outliers, all continuous variables are winnowed at the 1% and 99% levels.

3.2. Measures

occupational pension. Based on previous studies (Shan & Park, 2023; Zheng et al., 2023), we use the amount of occupational pension (LPensions) in the annual reports of listed companies. In the robustness test, we use the DID enacted by the 2010 Social Security Law to measure it.

Strategic and responsive CSR. Learning from previous methods, strategic CSR (LSCSR) is the sum of employee responsibility, consumer responsibility and product responsibility, responsive CSR (LRCSR) is the sum of environmental responsibility and community responsibility (Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006; Porter & Kramer, 2011). This part of data in the benchmark regression comes from the social responsibility report of listed firms disclosed by Hexun.com (Gu, Liu, & Peng, 2022; Nwagbara & Reid, 2013; Michael E Porter & Mark R Kramer, 2006).

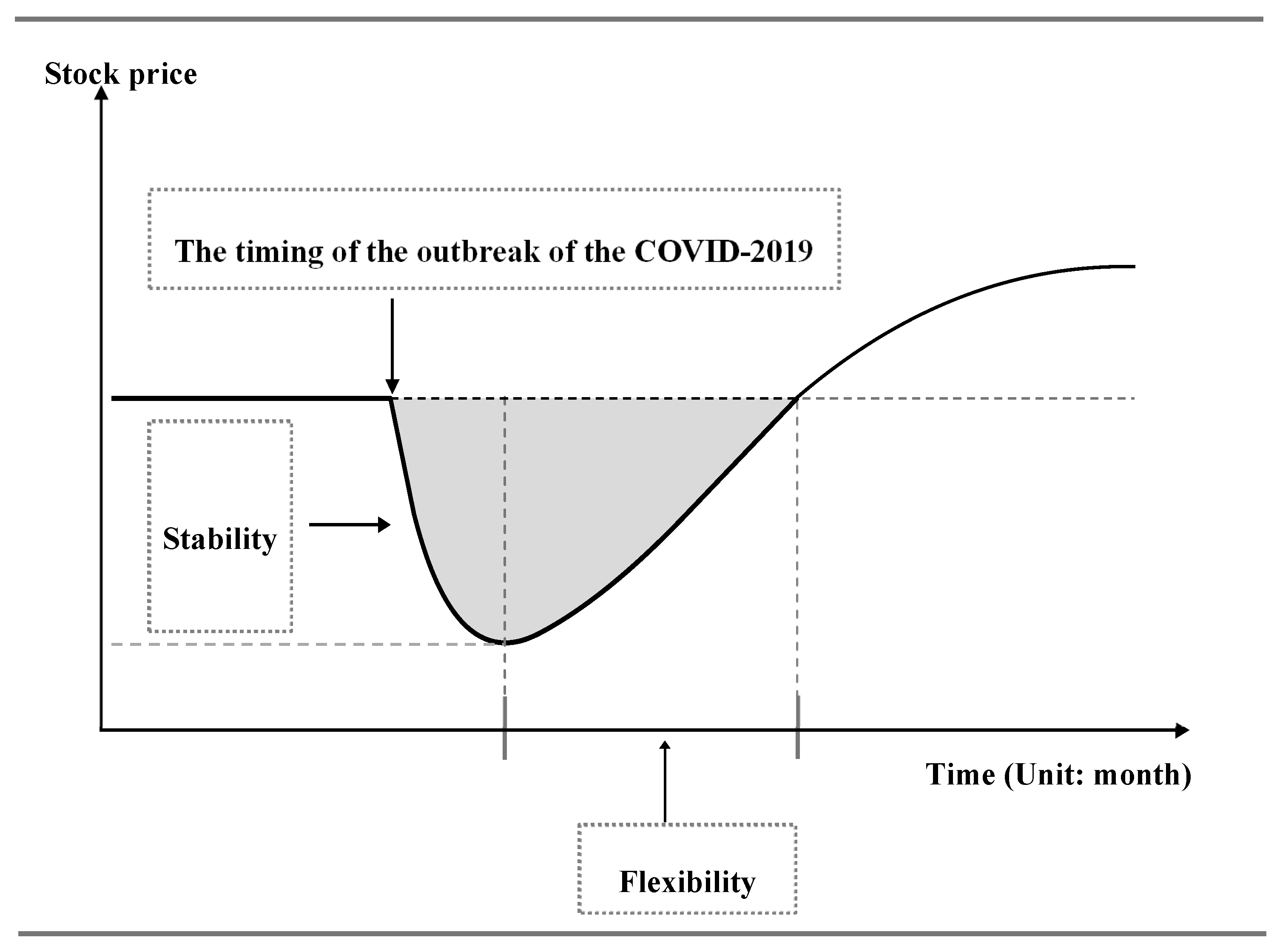

Organizational resilience. We categorized resilience into stability and flexibility, as outlined by DesJardine et al (M. DesJardine, P. Bansal, & Y. J. J. o. M. Yang, 2019b; M. Sajko, C. Boone, & T. J. J. o. M. Buyl, 2021b). LStability refers to the maximum loss in stock price. To make the final result more accurate and objective, we used the relative value of the maximum loss. To illustrate this conclusion, this study introduced the reverse coding method of Fan et al. (2001), to measure stability. LFlexibility refers to the time taken for stock price to recover from the lowest point to 30% of the initial efficiency level, as measured using the reverse coding method. Data are from the Wind database.

We clearly represent the measurement dimensions of resilience in

Figure 2.

Aging population. One of the moderating variables of this paper is the degree of aging (LAging). Referring to previous studies, this paper used the percentage of the population over 65 years old in each city from China Statistical Yearbook data to measure this variable (Bellino et al., 2020; B. Hu, Peng, Zhang, Yu, & Health, 2020).

Minimum wage. Minimum wage is one of the moderating variables in this paper (LMiwage). Referring to previous studies, this paper searched the official government websites, such as the provincial human resources and social security departments. It manually organized the data of minimum wage standards in the local areas (Du & Wang, 2020).

Digital transformation. The dependent variable of this paper is the degree of digitalization (LDigitaltrans). Concerning previous studies, this paper adopted the Digital Transformation Index of Chinese Listed Companies, jointly published by the National Finance Team of Guangdong Institute of Finance and the Editorial Board of Research in Financial Economics, to measure the degree of digital transformation (LDigitaltrans) (H. Liu, Wang, Liang, & Wang, 2022; Jingyong Wang, Song, & Xue, 2023). The larger the value of the Digital indicator, the higher the enterprise’s digital transformation degree.

Marketing capability. The moderating variable in this paper is marketing capability (LCmkt). In this paper, the stochastic frontier model (SFA) is used to measure the marketing capability. The stochastic frontier production function reflects the functional relationship between the input mix and the maximum output under the specific technical conditions and the given combination of production factors (Mishra & Modi, 2016). In this paper, sales revenue is taken as the output index, and sales expenses, intangible assets and customer relationship management are taken as the input index of marketing capability (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Among them, sales expense reflects marketing expenditure; Intangible assets reflect brand effect, intellectual property and goodwill, etc. The level of customer relationship management reflects sales from repeat customers (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Based on the above analysis, this paper builds a stochastic frontier model of marketing capability: sales revenue =f (sales expenses, intangible assets, customer relationship management). Then, through the regression analysis of the above model, the non-negative inefficiency item in the model is calculated, and then the exponential operation is carried out to obtain the value of marketing capability.

Controls. Referring to previous studies (M. DesJardine et al., 2019b; Sajko et al., 2021b), to control for the influence of other factors, this study chose enterprise size (LSize), asset-liability ratio (LLev), return on assets (LROA), cash flows (LCashflow), shareholding concentration (LTop5), age of business (LListAge) and growth capacity (LRevenue) as the control variables. The data were obtained from the CSMAR (China Economic and Financial Research Database) database.

6. Conclusions and Discussions

The main purpose of our study is to investigate the impact of occupational pension on CSR, as well as the impact of CSR on organizational resilience. The findings of this study suggest that depending on the cost stickiness of CSR, occupational pension induces firms to reduce responsive CSR investments and increase strategic CSR under the cost stickiness effect of occupational pension premiums. Moreover, strategic CSR increases organizational resilience and responsive responsibility decreases organizational resilience. In addition, this study explores the moderating effects of population aging, minimum wage, digital transformation, and marketing capabilities on the above relationships.

6.1. Main Conclusions

First, the study’s main findings are as follows: occupational pension reduces reactive CSR and increases strategic CSR investment based on the cost stickiness theory. The cost stickiness of strategic CSR cost stickiness is high. Enterprises are reluctant to pay high adjustment costs under the cost pressure of paying for occupational pension. Instead, they increase strategic CSR to obtain additional benefits. The cost stickiness of responsive CSR is low, so under the cost pressure of paying for occupational pension, enterprises are willing to pay lower adjustment costs to reduce the costs caused by responsive CSR investment.

Second, different CSR inputs have varying effects on organizational resilience. Strategic CSR inputs promote the formation of organizational resilience, while responsive CSR inputs inhibit it. As a long-term corporate investment, strategic CSR aims to strengthen a company’s core business and create an intersection of interests between the company and its strategic stakeholders. This increases the stability and flexibility of the company and promotes the formation of organizational resilience. On the other hand, responsive CSR may prioritize short-term benefits, which can hinder efforts to improve the core business of the enterprise, negatively impact its stability and flexibility, and impede the development of organizational resilience.

Third, the minimum wage moderates the relationship between occupational pension and CSR. Our research shows that the minimum wage and occupational pension share similarities. Both are forms of labor protection that increase the burden on firms. The cost effect of minimum wage is similar to the effect of firms’ contributions to occupational pension. Therefore, we conclude that the minimum wage worsens the negative relationship between occupational pension and responsive CSR. The study shows that the minimum wage negatively moderates the positive correlation between occupational pension and strategic CSR. Additionally, the study finds that population aging has a moderating effect on the relationship between occupational pension and CSR. Population aging shocks the labor market and increases the cost of hiring employees for firms, which in turn increases the burden on companies. Therefore, population aging exacerbates the negative relationship between occupational pension and responsive CSR. Furthermore, population aging mitigates the positive relationship between occupational pension and strategic CSR.

Forth, our study shows that digital transformation moderates the relationship between CSR and organizational resilience. It enables firms to access information quickly and accelerates their efficiency in absorbing resources, facilitating the transformation of strategic CSR into organizational resilience. Additionally, digital transformation mitigates the reduction of responsive CSR to organizational resilience. Marketing capabilities moderate the relationship between CSR and organizational resilience. Our study shows that marketing capabilities help deliver intra-firm messages to stakeholders more effectively. Additionally, firms with higher marketing capabilities accelerate stakeholder support for the firm, which facilitates the transformation of strategic CSR into organizational resilience. Similarly, companies with greater marketing capabilities can reduce the negative impact of responsive CSR on organizational resilience.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

First, to clarify the controversy surrounding the motivation of Chinese firms to fulfill their CSR from the integrated perspective of the cost stickiness theory. This study categorizes CSR into responsive and strategic, based on the cost stickiness theory (M. E. Porter & M. R. J. H. b. r. Kramer, 2006), and examines how the dynamic balance between the responsive and strategic institutional fit is achieved in the process of CSR fulfillment (M. E. Porter & M. R. J. H. b. r. Kramer, 2006). The study’s findings offer a theoretical framework for why companies adopt CSR, enriching the application of cost stickiness theory and stakeholder theory.

Second, This study contributes to the existing literature on enhancing organizational resilience processes from a CSR perspective, based on the context of COVID-19. Previous literature has primarily focused on the capability view of organizational resilience, which emphasizes resilience as an organizational characteristic (M. DesJardine et al., 2019b; Do, Budhwar, Shipton, Nguyen, & Nguyen, 2022; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Sajko et al., 2021b). This study examines the relationship between CSR and organizational resilience from the perspectives of stakeholder theory, resource-based theory, and signaling theory. The findings indicate that strategic CSR enhances organizational resilience, while responsive CSR inhibits organizational resilience. This study explains how to enhance organizational resilience in the context of COVID-19. It expands research understanding of CSR and organizational resilience and enriches the application of stakeholder theory, resource-based theory, and signaling theory.

Finally, this study offers a unique contribution to the marketing literature by considering the moderating role of marketing capabilities in the relationship between CSR and organizational resilience. The incorporation of marketing capabilities into a model of the relationship between CSR investments and organizational resilience sheds further light on the boundary mechanisms of the impact of CSR on organizational resilience. Compared to previous studies (Mishra & Modi, 2016), this study analyzed the moderating effect of marketing capabilities on the relationship between CSR and organizational resilience. The findings suggest that firms with higher marketing capabilities contribute more to organizational resilience through strategic CSR. Additionally, it was found that responsive CSR had a weaker inhibitory effect on organizational resilience for firms with higher levels of marketing capabilities. Firms with high levels of marketing capability can effectively correct the degree of deviation between responsive CSR and the firm’s core business. This study enriches and expands the explanatory scope of stakeholder theory, resource base theory, and signaling theory from the perspective of marketing capability.

6.3. Management Implications

The study’s findings aid policy makers in comprehending and evaluating the precise effects and extent of influence of the occupational pension system. Additionally, the study’s results assist corporate managers in determining the direction of optimization for CSR investment strategies when confronted with labor cost shocks, and in enhancing the organization’s risk-resistant capability while fulfilling social responsibility practices. In times of peace, managers should be prepared for potential risks, predict changes in the external environment, proactively adapt to market fluctuations, continuously acquire high-quality resources, and make timely adjustments to their corporate development strategies to improve the organizational resilience of their enterprises.

First, companies should increase their investment in strategic CSR, such as product responsibility and consumer responsibility. Strengthening customer relationship management can effectively improve the organizational resilience of enterprises and promote high-quality development and sustainable operation (Ntounis, Parker, Skinner, Steadman, & Warnaby, 2022; Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2022). Simultaneously, improving awareness of product innovation and avoiding product homogenization are also important for enhancing the organizational resilience of enterprises (J. Liu, Yue, Yu, & Tong, 2022). In the process of business practice, enterprises should accelerate digital transformation and upgrading to improve the efficiency of scarce resource acquisition and information transfer.

Secondly, enterprises should invest in responsive CSR moderately. This is because over-investment in responsive CSR, after satisfying the conditions of legitimacy and consistency, can divert resources from a firm’s core business, which is not conducive to organizational resilience and sustainable operations (Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Friedman, 1970). Companies should evaluate and measure their investment in responsive CSR in a timely manner and manage it appropriately to maintain a balance between strategic and responsive CSR.

Thirdly, improving marketing capabilities can enhance the corporate brand image, promote resource transformation and information transfer efficiency, and improve the quality of corporate development (Mishra & Modi, 2016). Marketing competence helps firms fulfill the process of strategic CSR, improves their organizational resilience, and avoids the consumption and destruction of firms’ strategic resources due to over-investment in responsive CSR.