1. Introduction

Rice is one of the major staple foods in Nigeria. It was observed that the high level of importation of the commodity resulted from a short supply from local production (Akpan et al., 2014) [

1]. In a bid to boost local production, the Federal Government of Nigeria banned the importation of rice into the country (Ukwuije & Chukwukere, 2021) [

2]. According to Terwase and Madu (2014) [

3], the policy led to a small increase in the supply of rice in local markets, with prices skyrocketing and the smuggling of the commodity intensifying. The negative economic impact arising from the shortfall in the supply of rice has been attributed to various factors, including the lack of engagement or minimal engagement of youths in the rice value chain in the country. Additionally, apathy by the youths towards agriculture has been identified as a major factor responsible for the short supply of the commodity in Nigeria.

Consequently, the government initiated various agricultural programs to empower the youth and encourage their participation in agriculture. Notable among such programs are the Youth Employment in Agriculture Programme (YEAP), launched by the Federal Government in 2016 (ILO, 2016) [

4]; the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme, launched in 2015 to provide loans to smallholder farmers for the cultivation of various crops, including rice (Development Finance Department, Central Bank of Nigeria, 2021) [

5]; and the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA), which aimed at transforming Nigeria's agriculture and creating jobs, especially for the youth along the value chains of many crops (African Development Bank, AfDB, 2013) [

6].

Youth engagement in agriculture is key to solving Nigeria's food problem and helping to earn foreign exchange to grow the economy. Therefore, ensuring equitable gender access and opportunities along rice value chains is necessary to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals of eradicating poverty and hunger, and promoting gender equality. However, there is a dearth of literature on gender equity opportunities among youth engaged in the rice value chain in the South-East region of Nigeria using the Modified Gender Equity Index (MGEI). Thus, there is a knowledge gap that this study intends to fill. Understanding the level of gender equity in opportunities among male and female youth actors and the constraints to male and female youth engagement in the rice value chain could guide the development of strategies and interventions to address the issue.

2. Meterials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

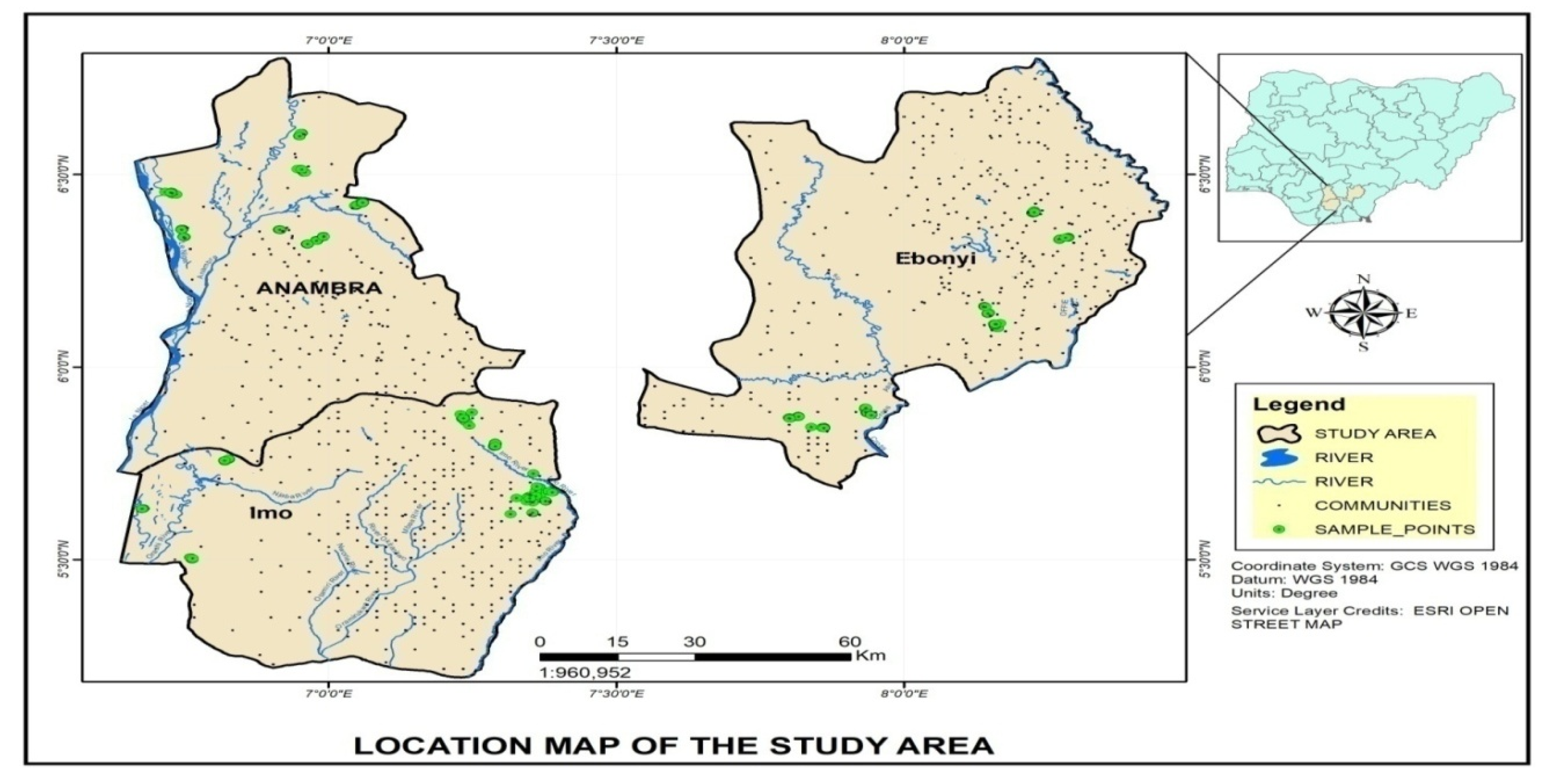

The study was conducted in Anambra, Ebonyi and Imo states of the South-East geopolitical zone of Nigeria. These states are known for their production, processing and marketing of rice. Anambra state lies within Latitudes 6

o45' and 5

o44' and Longitudes 6

o36' and 7

o29'. It has a population of about 4,177,828 persons and land area of 4,865km

2 ((National Bureau of Statistics, NBS, 2011). Ebonyi state lies within Longitudes 7

o30ˈE and 8

o30ˈE and Latitudes 5

o40ˈN and 6

o45ˈN. It has a land area of 5,935 km

2 and a population of 2,253,140 persons. Imo State has a population of 3,927,563 people and a land area of 5,430 km

2 (National Bureau of Statistics, NBS, 2011) [

7], and lies within Latitude 4°45' and 7°15'N and Longitudes 6°50' and 7°25'E. Agriculture is the major economic activity of the people, although a few are civil servants, business people and artisans. Mixed cropping is widely practiced and the major crops grown are oil palm, cereals and tuber crops. Animal husbandry and fisheries are also common. The map showing the study area is presented in

Figure 1.

2.2. Data and Sampling Procedures

The data used for this study were collected from household survey conducted in Anambra, Ebonyi and Imo States. The multi-stage sampling technique was used in the selection of the sample. The respondents are youth producers (farmers), processors and marketers who were randomly selected for the study. In the first stage, 2 agricultural zones were chosen from each of the selected states giving a total of 6 agricultural zones. The second stage involved random selection of 2 Local Government Areas (LGAs) from each of the selected agricultural zones giving a total of 4 LGAs for each state and 12 LGAs for the three states. In the third stage, 2 communities from each of the selected LGAs were randomly selected giving a total of 8 communities for each state and 24 communities for the three states. In the fourth stage, 2 villages were selected from each of the selected communities giving a total of 16 villages for each state and 48 villages for the three states.

To ensure representativeness of the sample, a pre-survey sampling frame was determined by compiling lists of male and female youth rice producers, processors and marketers in the selected villages in the 3 states. The age bracket of youth (18 - 35years) was used for this study. The lists of youth rice producers, processors and marketers were compiled by the Agricultural Extension Officers at the Local Government Areas, Market Heads and Traders Association. The lists put together served as the sampling frame from which the sample was drawn. The Sample frame was stratified into different actors which gave a sample frame of 282 youth households who are producers, 128 processors and 211 youth marketers across the chains. Finally, a stratified random sampling was then employed to select 212 youth producers, 86 youth processors and 178 youth marketers for the study. These gave a sample size of 476 youth actors.

The variables on which data were collected include, socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents, such as gender, age, level of education, household size, membership of cooperatives, number of extension agent visits per annum, distance to actor’s node, information access, labour force participation, credit access, value of output, value of intermediate products, capital invested, population of male and female actors in rice value chains, inputs and outputs, cost and returns of the respondents.

2.3. Empirical Methodology

The study employed the Modified Gender-Equity Index (MGEI). The Modified Gender-Equity Index (MGEI) considers situations of gender inequity that are unfavourable towards men and women, applying a methodological change to the definition of the gender gap for the three GEI dimensions. The opportunities were based on indicators such as formal education (basic education) gap, access to credit gap and membership of cooperative association. It was aimed at comparing the proportions of women and men with a particular characteristic (i) in absolute terms, stated as in (Fernández-Sáez et al, 2013) [

8]:

MGapij = Gender gap for the ith characteristic for the jth node of the chain

Wij= Number of women with the ith characteristic for the jth node of the chain

Mij= Number of men with the ith characteristic for the jth node of the chain

Pwij= Proportion of women with ith characteristic for the jth node of the chain

Pmij= Proportion of men with ith characteristic for the jth node of the chain

nwj= Total number of women for the jth node of the chain

nmj= Total number of men for the jth node of the chain

The proportions have values of between 0 and 1, from which it results that: − (Pwi + Pmi) ≤ Pwi–Pmi≤ Pwi + Pmi, whilst dividing by PWi + Pmi results in − 1 ≤ MGapi ≤ 1.

The interpretation of the modified gap is the following:

- i.

If MGapi = 0, the numerator of the gap equals 0, with both proportions coinciding, and a situation of equity is reached, since there is no disparity between women and men for the ith characteristic.

- ii.

If MGapi = -1, then Pwi-Pmi = - (Pwi+Pmi) and therefore Pwi = 0, this indicates a situation of maximum inequity towards women. Negative gap values reflect the existence of inequity towards women, and the closer the gap is to -1, the greater this inequity becomes.

- iii.

If MGapi = 1, then Pwi-Pmi = Pwi+Pmi and consequently, Pmi = 0, indicating a situation of maximum inequity towards men. Positive gap values reveal the existence of inequity towards men, which increases the closer the gap value, is to 1.

However, interpreting the gap in absolute terms enables the distance between both genders to be measured: gap values close or equal to 0 indicate an absence of distance (equity), whereas the closer the values become to unity, the greater the gap between both genders for the characteristic considered (inequity). From this gender gap, the gender-equity index (GEI) will be calculated using the GEI model stated as:

Where,

GEIj = Gender Equity Index for the jth node of the chain

= Gender gap in formal education (will be determined using equation 1)

= Gender gap in credit access (will be determined using equation 1)

= Gender gap in membership of cooperative (will be determined using equation 1)

In this case, GEI values -1 implies women inequity (favouring men), 0 (equity opportunities) and 1 entails men inequity (favouring women).

The value added by gender for each node of the chain was calculated using Value Addition model, stated as (FAO, 2005) [

9]:

Where,

VAij =Value added by the ith actor for the jth node

Yij= value of output of the ith actor for the jth node

Uij= Value of intermediate input of the ith actor for the jth node

Thus, to calculate the value added, all costs and sales for the relevant stages have to be measured. In addition, the underlying product and input prices are essential. This also identify the gender that contributed to the highest share of value added for each node, and which node contributed to the lowest if there is an overall positive value added. However, the overall value added was calculated using the model stated as (FAO, 2005) [

9]:

3. Results

3.1. Gender equity opportunities along the rice value chain is presented in Table 1

Table 1 show that there is disparity between male and female actors in the areas of education, access to credit and membership to value chain association. For producers, result indicated negative gap value of -0.03 for education, -0.33 for access to credit and -0.28 for membership to association which reflected the existence of inequity towards the female producers, although, the education gender gap between the male and female producers was -0.03 indicating a slight disadvantage for female in terms of formal education. The Modified Gender Equity Index (MGEI) was -0.21 which implies female inequity in rice production in the research area (21% disadvantage compared to the male).

The education gap value for processors was -0.02 indicating minimal disparity in formal education between male and female which is unfavourable towards female. Access to credit gap value for processors was 0, indicating equity which means there is no disparity between male and female in access to credit. The gap value for membership to association for processors was -0.62 reflecting significant gender gap in representation and membership of value chain association which is unfavourable towards the female. The MGEI for rice processors was -0.21 which implies inequity towards female in rice processing in the research area (21% gender equity disadvantage for females compared to males).

Rice marketers’ education gap value was 0.01 which implies insignificant disparity in formal education between male and female actors, although unfavourable towards the male. The gap value for access to credit was 0.17 which indicate slight disadvantage for male in access to credit. Membership of association gender gap value was -0.30 indicating gender gap between male and female favouring men. The MGEI for marketers was -0.04 which implies women inequity (4% gender inequity towards the female favouring male).

Therefore, the level of gender equity opportunities for youth rice producers, processors and marketers in the research area using the MGEI was -0.21, -0.21 and -0.04 respectively which implies gender inequity that were unfavourable towards the female youth. This result shows that there is inequitable distribution of opportunities among male and female youth actors in rice value chain in the study area

3.2. Net Return, Value Added and the Share of the Value Added by Gender along the Rice Value Chain

Table 2 shows that the youth male and female rice producers earned revenue per hectare of ₦254,800 and ₦225,400 respectively and incurred total cost of production per hectare of ₦216,190 and ₦169,790 respectively. This implies that the male youth rice producers earned higher revenue per hectare than the female youth rice producers while, the male youth rice producers incurred higher cost than the female rice producers. The female youth rice producers had a higher net return of ₦47,650 per hectare while the male youth rice producers had net return of ₦46,550. The results on return to naira spent shows that one naira invested in rice production in the study area would return ₦22.35 to the male youth rice producers and ₦26.81 to the female youth rice producers, which implies that the female youth rice producers earn higher net return in rice production than the male rice producers. This contradict the findings of Ruvuna & Mweruli, (2021) [

10] that male are more profitable in rice production than the female rice producers. Generally the results on net return and return to naira invested of youth male and female producer shows that rice production is a profitable farm enterprise in the study area. This is in line with the findings of Ewuzie et. al. (2020) [

11] that rice production is very profitable.

The analysis of the cost and returns of rice processing per ton by gender is presented in

Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the youth male and female rice processors earned revenues of ₦12,600 and ₦12,600 per ton respectively and incurred total costs of ₦7,885 and ₦6,690 respectively. The net returns per ton for male youth and female youth rice processors were ₦4,715 and ₦5,910 respectively. This result implies that female youth rice processors had a higher net return than male youth rice processors in the study area. Results on Return on naira spent shows that one naira invested in rice processing in the study area would return ₦59.79 and ₦88.34 to the male and female rice processors respectively. This implies that female rice processors earned higher return on naira spent than the male rice processors and this indicates that the female youth processors incurred lower cost (₦6,690) per metric ton of rice processed compared to the male youth marketers (₦7,885). Based on the findings, it can be concluded that rice processing is profitable in the study area. This is in line with the findings of Ewusie, et. al

., (2020) [

11] and Ruvuna & Mweruli (2021) [

10] that rice processing is profitable business.

Cost and Returns of Rice Marketing per ton

The analysis of the cost and returns of rice marketing per ton by gender are presented in

Table 4.

Table 4 indicates that the male and female rice marketers earned revenue of ₦195,170and ₦192,300 per metric ton respectively, and incurred total costs of ₦168,000 and ₦165,000 respectively. The net return per metric ton for youth male and female rice marketers were ₦14,930 and ₦17,310 respectively. Additionally, results on Return on naira spent shows that every naira invested in rice marketing in the study area, the female youth marketers receives higher return (₦9.89) compared to the male (₦8.28) to the male. Therefore, the female youth rice marketers have a higher net return and return on naira spent than the male youth rice marketers. Based on the findings, it can be concluded that rice marketing in the study area is profitable. This is in line with the findings of Ewusie, et. al

., (2020) [

11] and Ruvuna & Mweruli (2021) [

10] that rice marketing is a profitable business.

Value added and share of value added

The result of the value added and share of value added by gender in rice value chain is presented in

Table 5.

For the producers, the value added per ton by male youth was ₦26,061 and female youth was ₦24,429. The total value added per ton by youth male and female rice producers was ₦50,490. For the processors, the value added per ton by male youth was ₦8,400 and female ₦8,600. The total value added by male and female youth rice processors was ₦17,000. The value added by male youth marketers was ₦17,570 and female youth rice marketers were ₦19,200. The total value added by male and female youth rice marketers was ₦36,770.

The total value added by male and female youth in rice value chain was ₦52,281 and ₦52,229 respectively, and the total value added by youths in the study area was ₦104,510. The overall value added indicates that there is relatively small difference between the contributions of male and female actors in the value chain. The value added share by male youth producers, processors and marketers were 51.62%, 49.41% and 47.78% respectively. This implies that the share of value added by male actors decreased along the rice value chain from producers with the highest value added share and the marketers with the least value added share. The value added share by female youth producers, processors and marketers were 48.38%, 50.59% and 52.22% respectively. It implies that the share of value added by actors increased along the rice value chain from the producers with the least value added share and the marketers with the highest value added share. This finding is in agreement with the findings of Osuji et. al

., (2017) [

12] and Igwenagu et. al

., (2020) [

13] that net value added increased along the chain thereby explaining incremental cost and complementary returns.

3.3. Constraints to youth engagement in rice value chain.

Table 6 show constraints to youth engagement in rice production. The table shows that the most commonly mentioned factors were lack of capital to start up rice production (75.47%), lack of access to credit (75.47%), drought (67.93%), lack of access to better technology (60.38%), rice production is very tedious (58.49%) and high cost of hiring machines/high operating cost (57.55%). The major factors that limit female youth engagement in rice production in the study area were, lack of capital of capital to start up rice production (94.34%), rice production is tedious/stressful (73.58), lack of access to credit (71.70%), flooding (64.15%), high cost and shortage of labour (62.26%), lack of access to better technology (62.26%), high cost of hiring machines/high operating cost (60.38%) and lack of know how/skills (50.94%). Male and female youth producers mentioned lack of capital and access to credit the major constraints. According to Mulema et. al. (2021) [

14], capital is required for the purchase of inputs and equipment which in most cases are not affordable by youths. Availability of capital according to Udemezue, (2019) [

15], will enable youth producers to access assets and essential inputs for production. Rice production was seen as been stressful by most male and female youth producers which is in line with the findings of Yami et. al. (2019) [

16] that, agricultural production is laborious and offers less in return. Mulema et. al. (2021) [

14], stated that majority of youth engaged in production activities of rice value chain considered rice production as tedious and less profitable. Majority of male and female youth producers encountered unfavourable weather conditions (drought and flooding) which affected the quantity and quality of output produced in that farming season in the study area.

Table 7 show constraints to youth engagement in rice processing. The table shows that majority (88.37%, 69.77%, 69.77%, 55.81, 55.81% and 46.51%) of the male youth rice processors reported that the major constraints that limit youth engagement in rice processing were that rice processing is stressful/tedious, lack of startup capital, insufficient know how/skills, lack of access to improved technology, and high cost of machines, maintenance, operating respectively. Also, 93.02%, 88.37%, 79.07%, 60.47%, 55.81%, 46.51% and 46.51% of the female youth rice processors reported the constraints of insufficient skills, high cost of machine/maintenance/operating, lack of capital, lack of access to credit, marital challenges and responsibilities, high labour cost and lack of improved technology. Majority of male and female youth processors are face the problem of capital which limits their access to improve technology, Mulema et. al. (2021) [

14]. In addition, lack of access to improved technology and high cost of machines/maintenance is one of the major constraints to youth engagement in rice processing in the study area. Most processing machines according to Linn & Maenhout (2019) [

17] are outdated, which leads to frequent machine breakdowns, high cost of repairs and maintenance and poor quality of processed rice. Insufficient knowhow/skill on rice processing is a challenged to male and female youth processors. Possession of specialized skills and knowhow in rice processing is important for management of the enterprise, (Robinson-Pant, 2016) [

18].

The constraints to youth engagement in rice marketing are presented in

Table 8. The table shows that the major constraints faced by male rice marketers were lack of access to credit (92.14%), lack of capital to startup (85.39%), rice marketing is a tedious business (89.89%), unstable market price (57.30%), lack of government support (44.94%) and poor access road (42.70%). Also, 88.76%, 78.65%, 70.79%, 61.80 and 33.71% of female youth rice marketers reported the constraints of lack of access to capital, poor access road; rice marketing is tedious, lack of access to credit, and lack of sensitization of the viability of rice marketing. Access to credit and capital is a major constraint and it’s needful for expansion of the rice business by the male and female youth marketers. Linn & Maenhout (2019) [

17] pointed out that capital and credit are needed to run or expand rice business and difficulty in accessing credit creates difficulties in the value chain. Male and female youth marketers were also constraint by poor access road. According to mulema et. al. (2021) [

14], poor access road leads to high cost of transportation, reducing profit of the youth marketer.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the study, it was concluded that there are disparities in access to education, credit and membership to cooperative associations among youth engaged in rice production, processing and marketing. It is recommended that technology transfer and extension services should be targeted at youth with focus on enhancing their productivity, improving the quality of product processed, and enhancing the overall efficiency of the rice value chain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Data curation, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Formal analysis, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Funding acquisition, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Investigation, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Methodology, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Project administration, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Resources, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Software, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Supervision, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Validation, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Visualization, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Writing – original draft, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide; Writing – review & editing, Akunna Tim-Ashama, Poycarp Obasi, Christopher Emenyonu, Uwanu Ibekwe and Bola Awotide.

Funding

This research was funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) under the grant 2000001374 “Enhancing Capacity to Apply Research Evidence (CARE) in Policy for Youth Engagement in Agribusiness and Rural Economic Activities in Africa” Project in the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IRB/IF-CA/003/2021) for studies involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) for the financial support. The usual disclaimers apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of Interest

References

- Agossadou, A.J; Fiamohe, R; Tossou, H.; Kinkpe,T. Agribusiness Opportunities for Youth in Nigeria: A Farmers Perceptions and Willingness to Pay for Mechanized Harvesting Equipment. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference of Agricultural Economists, Vancouver Canada, July 28-August 2, 2018; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, S. B.; Inimfon, V. P.; Samuel, J. U. Analysis of Monthly Price Transmission of Local and Foreign Rice in Rural and Urban Markets in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria (2005 to 2013). Inter. J. Agric. Forestry 2014, 4, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ukwuije, A.A.; Chukwukere, C. Trade Protectionism and Border Closure in Nigeria: The Rice Economy in Perspective. UJAH 2021, 22, 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwase, I.T.; Madu, A.Y. 2014 The Impact of Rice Production, Consumption and Importation in Nigeria: The Political Economy Perspectives. Inter. J. Sust. Devt & World Policy 2014, 3, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization, ILO (2020). Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020 :Technology and the Future of Jobs. International Labour Office, Geneva.

- Development Finance Department Central Bank of Nigeria (2021) Anchor Borrowers’ Programme (ABP) Guidelines. https://www.cbn.gov.ng/out/2021/ccd/abp%20guidelines%20october%2013%202021%20-%20final%20(002).

- African Development Bank Group, AfDB (2013). Agricultural Transformation Agenda Support Program – Phase 1 (ATASP-1), Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA-Summary). https://www.afdb.

- National Bureau of Statistics, NBS, (2011). Annual abstract of statistics. Federal Republic of Nigeria.

- Fernández-Sáez, J; Ruiz-Cantero, M. T; Guijarro-Garví, M; Carrasco-Portiño, M; Roca-Pérez, V; Chilet-Rosell, E & Álvarez-Dardet, C. Looking twice at the gender equity index for public health impact. BMC Public Health 2013, 659, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization(FAO)(2005): EASYPol. On-line resource materials for policy making. Analytical tools. Module 045. Commodity Chain Analysis. Impact Analysis Using Market Prices. www.fao.org/docs/up/easypol/332/CCA_045EN.

- Ruvuna, E.; Mweruli, F.T. Productivity and Profitability of Rice Producers of Kirimbi Marshland in Nyamasheke District, Rwanda: A Gender Wise Analysis. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies 2021, 6, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewuzie, C.O. , Ifedora, C.U.; Anetoh, J.C. Profitability of Actors In Rice Value Chain In Nigeria: A Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) 2020, 7, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Osuji maryann, N. , Ibekwe Eze C.C, Obasi U.C, Benchendo G.N., Nwaiwu I.O.U., Uhuegwulem I.; Anyanwu U.G. Analysis of Cassava Value Chain in South-East: A Seemingly Unrelated Regression Model Case. Conference Proceedings of the 18th Annual National Conference of The Nigerian Association Of Agricultural Economists Held At Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria 16"' - 19th October, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Igwenagu M.O., Ohajianya, D.O., Nwaiwu, I.U.O., Gbolagu, A.O.; Ehirim, N.C. Value Chain Mapping and Actors’ Value added Share in Catfish Value Chain in Imo State, Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences 2020, 18, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mulema, J. , Mugambi, I., Kansiime, M., Chan, H.T., Chimalizeni, M., Pham, T.P., & Oduor, G. Barrier and opportunities for youth engagement in agricbusiness: empirical evidence from Zanbia and Vietnam. Development in Practice 2021, 31, 690–706. [Google Scholar]

- Udemuzue, J.C. Agriculture for All: Constraints to Youth Participation in Africa. Current Investigations in Agriculture and Current Research 2019, 7, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yami,M. , Feleke, S., Abdoulaye, T., Alene, A.D., Bamba, Z., and Manyong, V. African Rural Youth Engagement in Agribusiness: Achievements, Limitations, and Lessons. Sustainability 2019, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Pant, A. Learning Knowledge and Skills for Agriculture to Improve Rural Livelihood. International Fund for Agricultural Development, Rome, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).