Submitted:

31 January 2024

Posted:

31 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

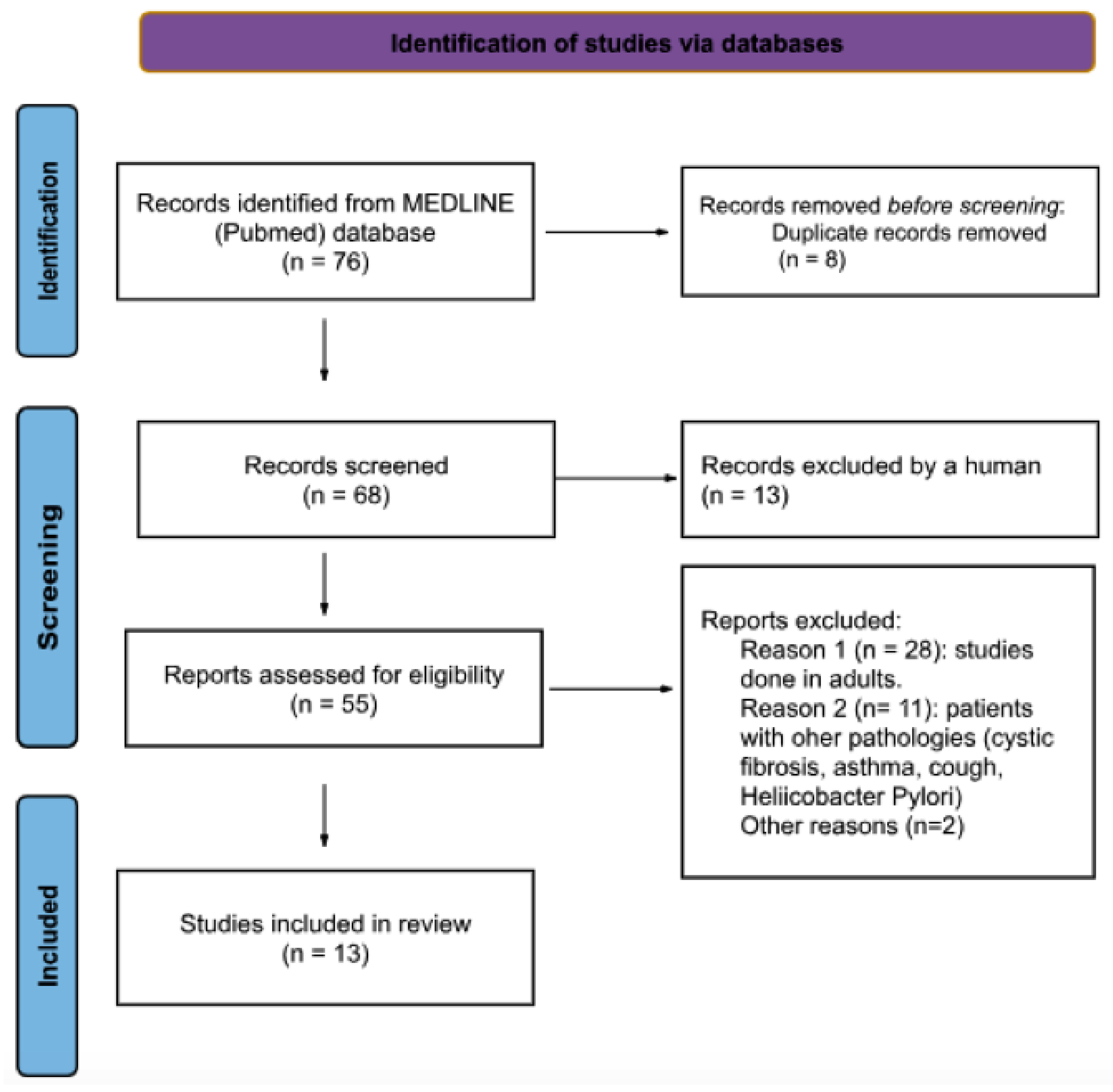

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- The study was a RCT.

- The target population was any pediatric patient [0 to 18 years of age] with GERD not secondary to another gastrointestinal pathology and receiving treatment with omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole or dexlansoprazole.

- One of the aims of the study was to evaluate the efficacy, AE and/of safety of PPI therapy.

- The intervention consisted of PPIs and was compared with another PPI, placebo, no treatment or alternative treatment.

- The outcome measure was effectiveness and/or safety of the different PPI for the treatment of GERD in the pediatric population.

2.3. Selection of studies and data extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

3.2. Effectiveness of PPI

3.2.1. Infant population

3.2.2. Children population

3.2.3. Others

3.3. Safety and adverse events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tighe MP, Andrews E, Liddicoat I, Afzal NA, Hayen A, Beattie RM. Pharmacological treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux in children. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2023, 8, CD008550. [Google Scholar]

- Armas Ramos H, Ortigosa del Castillo L. Reflujo gastroesofágico y esofagitis en niños. Soc Española Gastroenterol Hepatol y Nutr Pediátrica (eds) Trat en Gastroenterol Hepatol y Nutr pediátrica 2a ed [Internet]. 2008, 163–177. Available from: www.cedro.

- Sintusek P, Mutalib M, Thapar N. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children: What’s new right now? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023, 15, 84–102.

- Eiamkulbutr S, Dumrisilp T, Sanpavat A, Sintusek P. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children with extraesophageal manifestations using combined-video, multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH study. World J Clin Pediatr. 2023, 12, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singendonk M, Goudswaard E, Langendam M, van Wijk M, van Etten-Jamaludin F, Benninga M, et al. Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms in Infants and Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr [Internet]. 2019, 68, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird DC, Harker DJ KA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Infants and Children. Am Fam Physician. 2015, 92, 705–714. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenwald EC, Yogman M, Lavin CA, Lemmon KM, Mattson G, Rafferty JR, et al. Diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2018, 142, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Seok L, Ji Won K, Kook Lae L, Byeong Gwan K. Prevalence and predictors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in pregnant women and its effects on quality of life and pregnancy outcomes. J Gynecol Res Obstet. 2021, 7, 008–011. [Google Scholar]

- Lauriti G, Lisi G, Lelli Chiesa P, Zani A, Pierro A. Gastroesophageal reflux in children with neurological impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int [Internet]. 2018, 34, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea C, Khan R. There is an association between gastro-oesophageal reflux and cow’s milk protein intolerance. Ir J Med Sci. 2022, 191, 1717–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, a. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018, 66, 516–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer R, Vandenplas Y, Lozinsky AC, Vieira MC, Canani RB, Dupont C, et al. Diagnosis and management of food allergy-associated gastroesophageal reflux disease in young children—EAACI position paper. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dziekiewicz M, Mielus M, Lisowska A, Walkowiak J, Sands D, Radzikowski A, et al. Effect of omeprazole on symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children with cystic fibrosis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021, 25, 999–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Poddar, U. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in children. Paediatr Int Child Health [Internet]. 2019, 39, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 15. Davies I, Burman-Roy S, Murphy MS. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children: NICE guidance. BMJ [Internet]. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, Van Wijk MP, Omari TI, Tabbers MM, Benning MA. Efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011, 127, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management (CG184). 2019, (October 2019):1–27. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg184%0Ahttps://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg184/chapter/1-Recommendations#helicobacter-pylori-testing-and-eradication.

- Mohan N, Matthai J, Bolia R, Agarwal J, Shrivastava R, Borkar VV. Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Children: Recommendations of Pediatric Gastroenterology Chapter of Indian Academy of Pediatrics, Indian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ISPGHAN). Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 1163–1170.

- Lopez RN, Lemberg DA. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in infancy: a review based on international guidelines. Med J Aust. 2020, 212, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris J, Chorath K, Balar E, Xu K, Naik A, Moreira A, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines on Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Quality Appraisal of International Guidelines. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2022, 25, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen PL, Soto-Ramírez N, Zhang H, Karmaus W. Association between Infant Feeding Modes and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Repeated Measurement Analysis of the Infant Feeding Practices Study II. J Hum Lact. 2017, 33, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djeddi D, Stephan-Blanchard E, Léké A, Ammari M, Delanaud S, Lemaire-Hurtel A-S, et al. Effects of Smoking Exposure in Infants on Gastroesophageal Reflux as a Function of the Sleep–, Wakefulness State. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2018, 201, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin JM, Sachs G. Pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008, 10, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipasquale V, Cicala G, Spina E, Romano C. A Narrative Review on Efficacy and Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Children. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Trinh NTH, Chalumeau M, Kaguelidou F, Ruemmele FM, Milic D, et al. Pediatric Prescriptions of Proton Pump Inhibitors in France (2009-2019): A Time-Series Analysis of Trends and Practice Guidelines Impact. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2022, 245, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Lou I, Reilev M, Lødrup AB, Rubio-Valera M, Haastrup PF, Pottegård A. Use of proton pump inhibitors among Danish children: A 16-year register-based nationwide study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019, 124, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy EI, Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y, de Winter JP. Prescription of acid inhibitors in infants: an addiction hard to break. Eur J Pediatr. 2020, 179, 1957–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park YH, Seong JM, Cho S, Han HW, Kim JY, An SH, et al. Effects of proton pump inhibitor use on risk of Clostridium difficile infection: a hospital cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 29. van der Sande LJTM, Jöbsis Q, Bannier MAGE, van de Garde EMW, Coremans JJM, de Vries F, et al. The risk of community-acquired pneumonia in children using gastric acid suppressants. Eur Respir J. 2021, 58.

- Malchodi L, Wagner K, Susi A, Gorman G, Hisle-Gorman E. Early Acid Suppression Therapy Exposure and Fracture in Young Children. Pediatrics. 2019, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares M, Amil-Dias J. Proton-Pump Inhibitors: Do Children Break a Leg by Using Them? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021, 73, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitre E, Susi A, Kropp LE, Schwartz DJ, Gorman GH, Nylund CM. Association Between Use of Acid-Suppressive Medications and Antibiotics During Infancy and Allergic Diseases in Early Childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, e180315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Urrútia G, Romero-García M, Alonso-Fernández S. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799.

- Brockmeier AJ, Ju M, Przybyła P, Ananiadou S. Improving reference prioritisation with PICO recognition. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak [Internet]. 2019, 19, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini M-S, Jahanshahlou F, Akbarzadeh M-A, Zarei M, Vaez-Gharamaleki Y. Formulating Research Questions for Evidence-Based Studies. J Med Surgery, Public Heal [Internet]. 2023, 2, 100046. [CrossRef]

- Jadcherla SR, Hasenstab KA, Gulati IK, Helmick R, Ipek H, Yildiz V, et al. Impact of Feeding Strategies With Acid Suppression on Esophageal Reflexes in Human Neonates With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Single-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily esomeprazole for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in neonatal patients. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2013, 163, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loots C, Kritas S, Van Wijk M, McCall L, Peeters L, Lewindon P, et al. Body positioning and medical therapy for infantile gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014, 59, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolia V, Youssef NN, Gilger MA, Traxler B, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the treatment of erosive esophagitis in children: An international, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, double-blind (for dose) study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015, 60, S24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tolia V, Gilger MA, Barker PN, Illueca M. Healing of erosive esophagitis and improvement of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease after esomeprazole treatment in children 12 to 36 months old. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015, 60, S31–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Gremse D, Gold BD, Pilmer B, Hunt B, Korczowski B, Perez MC. Dual Delayed-Release Dexlansoprazole for Healing and Maintenance of Healed Erosive Esophagitis: A Safety Study in Adolescents. Dig Dis Sci [Internet]. 2019, 64, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohalinezhad ME, Imanieh MH, Samani SM, Mohagheghzadeh A, Dehghani SM, Haghighat M, et al. Effects of Quince syrup on clinical symptoms of children with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease: A double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract [Internet]. 2015, 21, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad I, Kierkus J, Tron E, Ulmer A, Hu P, Sloan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of rabeprazole in children (1-11 years) with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013, 57, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad I, Kierkus J, Tron E, Ulmer A, Hu P, Silber S, et al. Maintenance of efficacy and safety of rabeprazole in children with endoscopically proven GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014, 58, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker R, Tsou VM, Tung J, Sestini Baker S, Huihua Li, Wenjin Wang, et al. Clinical Results From a Randomized, Double-Blind, Dose-Ranging Study of Pantoprazole in Children Aged 1 Through 5 Years With Symptomatic Histologic or Erosive Esophagitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) [Internet]. 2010, 49, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter H, Kum-Nji P, Mahomedy SH, Kierkus J, Hinz M, Li H, et al. Efficacy and safety of pantoprazole delayed-release granules for oral suspension in a placebo-controlled treatment-withdrawal study in infants 1-11 months old with symptomatic GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010, 50, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter H, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, Gottrand F, Barker PN, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the treatment of GERD in infants ages 1-11 months. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012, 55, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain S, Kierkus J, Hu P, Hoffman D, Lekich R, Sloan S, et al. Safety and efficacy of delayed release rabeprazole in 1-to 11-month-old infants with symptomatic GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014, 58, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Pliego R, Asbun-Bojalil J, Anguiano-Robledo L. Revisión sistemática cualitativa del uso de cuestionarios para el diagnóstico de ERGE en pediatría. Acta Pediátrica México. 2016, 37, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Salas U, Camacho Eugenio J, Becerra Riaño K, Zárate Vergara AC, Tirado Pérez IS. La identificación del reflujo gastroesofágico fisiológico evita estudios innecesarios. Biociencias. 2020, 15, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999, 45, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilger MA, Tolia V, Vandenplas Y, Youssef NN, Traxler B, Illueca M. Safety and tolerability of esomeprazole in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015, 60, S16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kaguelidou F, Alberti C, Biran V, Bourdon O, Farnoux C, Zohar S, et al. Dose-finding study of omeprazole on gastric pH in neonates with gastro-esophageal acid reflux using a bayesian sequential approach. PLoS One. 2016, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fossmark R, Martinsen TC, Waldum HL. Adverse Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors-Evidence and Plausibility. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20.

- Maideen NMP. Adverse Effects Associated with Long-Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Chonnam Med J. 2023, 59, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanika LGT, Reynolds A, Pattison S, Braund R. Proton pump inhibitor use: systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruyne P, Ito S. Toxicity of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in children. Arch Dis Child. 2018; 103, 78–82.

- Yibirin M, De Oliveira D, Valera R, Plitt AE, Lutgen S. Adverse Effects Associated with Proton Pump Inhibitor Use. Cureus. 2021, 13, e12759. [Google Scholar]

- Lundell L, Vieth M, Gibson F, Nagy P, Kahrilas PJ. Systematic review: The effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use on serum gastrin levels and gastric histology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015, 42, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsuguchi A, Hoshino S, Kawami N, Gudis K, Nomura T, Shimizu A, et al. Influence of hypergastrinemia secondary to long-term proton pump inhibitor treatment on ECL cell tumorigenesis in human gastric mucosa. Pathol Res Pract [Internet]. 2020, 216, 153113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgadóttir H, Lund SH, Gizurarson S, Metz DC, Björnsson ES. Predictors of Gastrin Elevation Following Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020, 54, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiotani A, Katsumata R, Gouda K, Fukushima S, Nakato R, Murao T, et al. Hypergastrinemia in Long-Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Digestion. 2018, 97, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, DM. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use, Hypergastrinemia, and Gastric Carcinoids-What Is the Relationship? Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-H, Wintzell V, Ludvigsson JF, Svanström H, Pasternak B. Association Between Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Fracture in Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedberg DE, Haynes K, Denburg MR, Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Abrams JA, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors is associated with fractures in young adults: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int a J Establ as result Coop between Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA. 2015, 26, 2501–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients from birth to 18 years old with GERD not secondary to another gastrointestinal pathology | |

| Intervention | The administration of PPI for treatment of GERD | |

| Comparison | Another PPIs, another dose of PPIs, placebo, no treatment, alternative therapy for GERD [antacid or H2 blocker] | |

| Outcomes | Effectivenes of PPis:

|

|

| Study design | Restricted to RCTs | |

| Study | Objective, Participants, Diagnosis | Intervention (N, age) |

Control (N, age) |

Results | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEONATES | |||||

| Davidson et al. 2013 (ref) | Difference between esomeprazole and placebo. Neonates (PMA 28-44 w); clinical findings reproducible (8-h videocardiorespiratory monitoring) | Esomeprazole 0.5 mg/kg/day (n=25, 48.1 +/- 29.8 days) |

Placebo (n=26, 46.5 +/- 31.2 days) |

No statistically significant difference in the total number of GERD-related signs and symptoms from baseline observed by video and cardiorespiratory monitoring (esomeprazole:14.7%, placebo:14.1%, P=0.92) |

Esomeprazole: 23.1%, placebo: 34.6%. Most commonly reported: gastrointestinal disorders (9.6%), desaturation (2 esomeprazole, 1 placebo) |

| Study | Objective, Participants, Diagnosis |

Intervention (N, age) |

Control (N, age) |

Results | Adverse events |

| Jadcherla et al. 2020 (ref.) | Esophageal provocation–induced aerodigestive reflexes. Neonates GA < 42 w and PMA 34-60 w. Clinical symptoms of GERD and pH-impedance ARI ≥ 3% | Omeprazole 0.75 mg/kg/dose + FM bundle (n=25, PMA 41.2 +/- 3.1 w) |

Omeprazole 0.75 mg/kg/dose (n=24, PMA 41.4 +/- 2.2 w) |

Treatment groups did not differ in the frequency-occurrence of peristaltic reflex (OR = 0.8, 95% CI 0.4–1.6, P > 0.99). Follow-up in both groups: distal esophageal contraction and LES tone decreased, LES relaxation reflex less frequent (all P < 0.05) |

No found any AE in the study |

| INFANTS | |||||

| Winter et al. 2010 (ref) | Efficacy of pantoprazole; infants (1 and 11 m). Modified total GSQ-I >16 and a clinical diagnosis of suspected, symptomatic, or endoscopically proven GERD |

Pantoprazole 5 mg/day for infants 2.5 kg to <7 kg 10 mg/day for infants >7 kg to 15 kg (n=52, 5.15 +/- 2.81 m) |

Placebo (n=54, 5.04 +/- 2.81 m) |

OL phase: significant reduction in WGSSs from baseline (P < 0.001) with pantoprazole. DB phase: the decrease continued for both treatments groups, no significant differences of withdrawal rates due to lack of effectiveness |

AEs recorded: 29 pantoprazole group, 19 placebo group (no significant differences, all mild or moderate). Most common AEs in both groups: upper respiratory tract infections (13%) |

| Winter et al. 2012 (ref) | Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole; infants (1 to 11 m); GERD diagnosed by symptoms, confirmed by endoscopy or an investigator's determination of GERD | Esomeprazole 2.5 mg/day (3-5 kg) 5 mg/day (>5–7.5 kg) 10 mg/day (>7.5–12 kg) (n=39, 4.9 +/- 2.6 m) |

Placebo (n=41, 4.9 +/- 3.2 m) |

OL phase: 82.7% symptom improvement. DB phase: no significant differences between the treatment group and the placebo group regarding symptom worsening (38.8% vs. 48.5%, HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.35%-1.35%; P = 0.28) |

OL phase: 48% patients AEs. DB phase: 59% esomeprazole, 66% placebo. Most common: upper respiratory tract infection (15.4% and 9.8%, respectively). No serious AEs considered treatment related |

| Hussain et al. 2014 (ref) | Efficacy and safety of rabeprazole, infants (1 to 11 m), GERD resistant to conservative therapy and/or previous acid suppressive medications, I-GERQ >16 | Rabeprazole (n=178, 4.7 +/- 2.54) Rabeprazole 5 mg (n=90, 4.6 +/- 2.57) Rabeprazole 10 mg (n=88, 4.7 +/- 2.52 m) |

Placebo (n=90, 4.7 +/- 2.65 m) |

No differences in primary efficacy variables. Frequency of regurgitation (-0.79 vs -1.20 times/day; P=0.16) Mean increase weight- z scores (0.11 [0.329] vs 0.14 [0.295]; P= 0.440) I-GERQ score (-3.6 [-25%] vs -3.9 points [-27%]; P= 0.960) |

Similar rates of AEs (47%) both in the placebo and combined rabeprazole groups. Most common AEs: pyrexia (2% placebo, 7% rabeprazole), upper respiratory tract infection (6% vs 5%), GERD (8% vs 4%), and vomiting (6% vs 3%) |

| Loots et al. 2014 (ref) | Efficacy of LLP in GERD. Infants (birth-6 m). ph-impedance, monitoring, 8h video study, gastric emptying breath test, I-GERQ q |

Group 1 LLP + ES 1 mg/kg/day (n=12, 12 +/- 3w) Group 2 HE + ES 1 mg/kg/day (n=14, 12 +/- 3w) |

Group 3 LLP + AA (n=13, 14 +/-2 w) Group 4 HE + AA (n=12, 17 +/- 2 w) |

Vomiting was reduced in AA + LLP (P=0.042). LLP compared with HE produced greater reduction in total GER (P=0.056). Acid exposure was reduced on PPI compared with AA (P=0.043) |

No AEs correlated with treatment 5 patients AEs (urinary tract infection, constipation, diarrhea, vomiting). |

| Study | Objective, Participants, Diagnosis | Intervention (N, age) |

Control (N, age) |

Results | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tolia et al. 2010 (ref) |

Endoscopic healing of EE. Children 1-11 y. Endoscopically confirmed GERD |

Esomeprazole (8 w) <20 kg: 5 mg (n=26, mean 2.1 y, EE=12). ≥20 kg: 10 mg (n=31, mean 8.5 y, EE=16) |

Esomeprazole <20 kg: 10 mg (n=23, mean 2.5 y, EE=12). ≥20 kg: 20 mg (n=29, mean 8.3 y, EE=13) |

109 patients randomized: 49% EE. EE healed in 89%: <20kg/5mg 100%, <20kg/10mg 82%, ≥20 kg/10 mg 90%, ≥20 kg/20 mg 85% |

10/108 patients with AE related with esomeprazole (9.3%). 13 AE reported. Most common: diarrhea (n=3), headache (n=2), somnolence (n=2) |

|

Tolia et al 2010 (ref) |

EE healing and symptom improvement. Children 12-36 m with GERD. Diagnosis by clinic (PGA) and endoscopy |

Esomeprazole (8 w) 5 mg (n= 18, mean 21.8 m). 10 (56%) EE (28% LA grade A, 28% LA grade B). Baseline PGA: 45% mild, 50% moderate, 5% severe |

Esomeprazole (8 w) 10 mg (n=13, mean 22.5 months). 5 (39%) EE (23% LA grade A, 8% LA grade B, 8% LA grade C) Baseline PGA: 20% mild, 80% moderate |

31 patients: EE: 15 (48.4%), control: 100% healed. Final PGA: 5 mg: 45% none, 50% mild, 5% moderate. 10 mg: 20% none, 65% mild, 15% moderate |

Most common AE: vomiting, pyrexia and diarrhea |

|

Baker et al 2010 (ref) |

GERD symptom improvement. Children 1-5 years: GSQ-YC >3 and endoscopic HE (Hetzel Dent grade ≤2) or EE (Hetzel Dent grade > 2). |

Pantoprazole (8 w) 0.3mg/kg (LD): n= 18, 2.7 years (+/-1.6) |

Pantoprazole (8 w): 0.6 mg/kg (MD): n= 21, 1.9 y (+/-1.2) 1.2 mg/kg (HD): n= 21, 2.8 y (+/-1.3) |

60 patients (56 HE, 4 EE). Improvement in WGSS (HE population, 8w): LD: P < 0.001, MD: P = 0.063, HD: P < 0.001 Endoscopic healing: 100% of EE population |

Most common AE: upper respiratory infection, fever, diarrhea, rhinitis, vomiting, headache |

|

Haddad et al 2013 (ref) |

Endoscopic healing at 12 w. Children 1-11 years endoscopically/histologically GERD (Hetzel-Dent ≥1 and Histological Features of Reflux Esophagitis scale >0) and at least one symptom of GERD | Rabeprazole (12 w) <15 kg (LW): 5 mg (n=21, 2.4 +/-1.2 years, H-D score 1.7+/-0.97) ≥ 15 kg (HW): 10 mg (n=44, 7.6 +/-2.9 years, H-D score 1.5+/-0.70) |

Rabeprazole (12 w) < 15 kg (LW): 10 mg (n=19, 1.9 +/-1.1 years, H-D score 1.4 +/-0.60) ≥ 15 kg (HW): 20 mg (n= 43, 7.0 +/- 0.7 years, H-D score 1.4+/-0.62) |

108 patients: 87 endoscopic healing. LW/5mg: 82%, LW/10mg:94% HW/10 mg:76%, HW/20 mg:78% Change of GERD symptoms Severity scores: LW/5mg: -13.6, LW/5mg:-9 HW/10 mg:-10.6, HW/20 mg:-8.3 |

76% of children at least 1 AE, 5% serious AE. Cough (14%), vomiting (14%), abdominal pain (12%), diarrhea (11%) |

|

Haddad et al 2014 (ref) |

Endoscopic healing at 24 w. Children 1-11 years with endoscopic healing at 12 w in previous study (Hetzel-Dent 0 and Histological Features of Reflux Esophagitis scale = 0) |

Rabeprazole (12 w) <15 kg (LW): 5 mg (n=9, 2.4+/-1.24 years) ≥ 15 kg (HW): 10 mg (n=24, 7.7 +/-2.74 years) |

Rabeprazole (12 w) <15 kg (LW): 10 mg (n=8, 1.5+/-0.53 years) ≥ 15 kg (HW): 20 mg (n=23, 7.2 +/- 2.66 years) |

52 patients, 47 (90%) endoscopic healing. LW/5mg: 100%, LW/10mg:100% HW/10 mg: 89%, HW/20 mg: 85% Change of GERD symptoms Severity scores: LW/5mg: -3.8, LW/5mg:-3.6 HW/10 mg: -2.6, HW/20 mg:-3.0 |

63% at least 1 AE (5% severe). Upper respiratory tract infection (63%), vomiting (11%), abdominal pain (8%), diarrhea (6%). 5% related to medication |

|

Grense et al 2018 (ref.) |

Treatment emergent adverse events and healing of EE. Adolescents 12-17 years with symptoms and endoscopically confirmed EE and healing with dexlansoprazole 60 mg /day (8w) |

Dexlansoprazole 30 mg 16 w treatment period (n= 22, 14.6 +/- 1.41 years, LA grade A 61.5%, grade B 34.6%, grade C 3.8%) |

Placebo 16 w treatment period (n= 24, 14.8 +/- 1.75 years, LA grade A 56.0 %, grade B 44 %, grade C 0 %) |

62 patients 16 w treatment period Healing: Dexlansoprazole 82 % : grade A 82%, grade B 82%. Placebo 58%: grade A 87 %, grade B 13 % |

72.0% (D), 61.5% (placebo). More common headache (24.0% D, 15.4% placebo). ≥ 5% D: abdominal pain, nasopharingitis, sinusitis, upper respiratory tract infection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).