1. Introduction

Most disasters, whether natural or man-made, often trigger cascading disasters, as observed in the recent Turkish earthquake on February 6th, 2023. Cascading disasters result from an initial external event that initiates interconnected repercussions within a network, leading to more severe breakdowns (Helbing 2013; O’Brien and Federici 2020; Pescaroli and Alexander 2015). This phenomenon amplifies security risks, heightens vulnerability, and presents crisis management challenges (UN General Assembly 2016). A significant consequence of cascading disasters is the risk of power outages, which can cause infrastructure collapse and disrupt vital services like water supply, sewage systems, and food distribution (Miller and Pescaroli 2018). These power outages also profoundly impact mass communication during emergency response efforts, as they can lead to internet failures and render certain smartphone applications useless. Such limitations can hinder rescue and response operations, further complicating the already challenging task of saving lives during disasters.

CTermPort will focus on improving communication during crises for various stakeholders, including crisis translators and interpreters (CTIs), cultural mediators, and humanitarian actors. It proposes the development of a multilingual crisis terminology compilation, the CTermBank, downloadable onto smartphones, and a unified terminology search tool with the capability to browse existing termbanks. It aims to enhance response effectiveness and serves as a trusted reference point throughout the disaster cycle by integrating additional features, such as a browser for visual dictionaries (CTermVisio), a browser for pharmaceutical databases (CTermPharma), automated translation feature (CTermTrans), automated interpreting feature (CTermInt), and a live location sharing feature together with an instant messaging feature.

2. The Right to Access Crisis Terminology

Timely and accurate information is crucial for effective disaster response (O’Brien et al. 2018), especially in linguistically diverse contexts (O’Brien and Federici 2020). Language is a key component of emergency and disaster management, as emphasised during the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (Aitsi-Selmi et al. 2016). However, Crisis Translation and Interpreting (CTInt) remains a rare and underrepresented scientific subject.

Article 9 of the UN's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (UN ICCPR) protects "the right to freedom of expression" and "the right to seek, receive, and disseminate information" (UNICCPR 1966). Additionally, Article 26 of the same covenant prohibits "the use of language for discrimination" (UNICCPR 1966). Mendel's review of "freedom of information" laws highlights that it encompasses not just "access to information" but also the "free flow of information in society" (Mendel 2008). He discusses situations where there is a "legal right to information", citing an Italian court case where the failure to provide crucial information during an emergency was deemed a rights violation (Mendel 2008). Thus, access to disaster information is not only vital but can also have legal implications when denied.

The right to information, recognised as a fundamental human right at both national and international levels, extends to information access during crises (O’Brien et al. 2018). In "The Signal Code: A Human Rights Approach to Information During Crisis", Greenwood et al. (2017) emphasise the crucial role of information and communication technology in disaster response. They assert that during crises, access to information and the means to communicate it is a basic humanitarian need, available to all, regardless of the context or severity of the situation (Greenwood et al. 2017). This highlights the importance of knowledge during crisis response, empowering individuals to ensure their safety (O’Brien et al. 2018). However, despite this perspective, the role of translation and interpreting as mediating agents in these scenarios is often overlooked. Mowbray (2017) argues that international law acknowledges the need for CTInt policies, noting that translation and interpreting are frequently described as a 'right', primarily to preserve other rights, such as accessing legal services (O’Brien et al. 2018). International law aims to address gaps related to language-based discrimination during disasters. Many individuals rely on translation and interpreting for information accessibility, as accessible information is crucial for reducing vulnerability and enhancing resilience.

Disasters have a disproportionately negative impact on individuals with disabilities and impairments. The Sendai Framework emphasises the necessity of "inclusive, accessible, and non-discriminatory involvement" in effective disaster risk reduction (UNISDR 2016). In 2015, at the Dhaka Conference on Disability and Disaster Risk Management, a statement was endorsed, calling for the inclusion and leadership of people with disabilities in all crisis risk management efforts. This statement also highlights the importance of integrating "disability-inclusive disaster risk management" into Agenda 2030, as it enhances societal well-being, protects development gains, and reduces crisis-related losses. Furthermore, there were suggestions to align the European Disability Strategy 2010-2020 midterm review with the Sendai Framework (UNISDR 2016).

UN Special Rapporteur Tomaševski's 4-A paradigm (Tomašcevski 2001) assesses the right to education (UN CESCR 1999; HRC 2020) through the "availability, accessibility, acceptability, and adaptation" of resources. O'Brien et al. (2018) apply this paradigm to translation and interpreting in countries like Ireland, the UK, New Zealand, Japan, and the USA, to evaluate the provision of emergency information to linguistically diverse groups. The 4-A paradigm they use is as follows (Tomašcevski 2001):

-

1.

Availability: This involves recognising translation as a necessary product and service, ensuring its presence.

-

2.

Accessibility: It entails making translations free, accessible through various platforms, available in different modes, and in all relevant languages.

-

3.

Acceptability: This aspect ensures that the translation service maintains accuracy and suitability through safeguards and verification.

-

4.

Adaptability: Translation services should be adaptable to changing contexts, including evolving language needs, literacy levels, technological demands, new delivery methods, varying risks, and population movements.

The UN Institute of Environment and Human Security in Germany created a World Risk Index (Welle & Birkmann 2015) to assess nations' vulnerability to natural disasters. These five nations reveal their susceptibility through factors like exposure to hazards, demographics, governance, political culture, and disaster history. Important aspects considered include annual tourist numbers, official languages, additional common languages (indicating linguistic diversity), primary natural hazards, and each country's World Risk Index ranking.

O'Brien et al. (2018) assessed disaster response procedures in five nations, including Ireland, the UK, New Zealand, Japan, and the USA, with a focus on the involvement of translators and interpreters. The evaluation examined how these countries handle the dissemination of multilingual information during crises, particularly concerning disadvantaged groups.

Ireland's Framework for Major Emergency Management (FMEM) (Irish Government 2008) is accompanied by two key documents: the Guide to Managing Evacuation and Rest Centres (Irish Government 2015) and the Guide to Preparing a Major Emergency Plan (Irish Government 2008). Both documents emphasise the importance of translations (Irish Government 2015, Irish Government 2010) to ensure accessibility for disabled communities and individuals with reading and writing difficulties. This includes using Braille, large print, and clear language for those with limited language proficiency.

The UK's Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (CCA2004) (Cabinet Office 2004) and Guidance: Emergency Preparedness (GEP2012) (Cabinet Office 2012) address language and communication during crises, recognising the language needs of vulnerable populations. Translators and interpreters are considered volunteers, with support provided in Annex 14A (Cabinet Office 2012; O’Brient et al. 2018). However, the Guidance on Emergency Response and Recovery (GERR2013) (Cabinet Office 2013) suggests outdated approaches to deploying language support, relying on subcontracting. Foreign language assistance comes from the British Red Cross Multi-lingual Phrasebooks, faith community officials, or trained volunteers. While the guidance recommends including language support provisions, no coordinating initiative is designated, leading to delays in securing interpreters and translators during incidents like the 2017 Grenfell Tower Fire (Marsh 2017; O’Brien and Federici 2020; O’Brien et al. 2018) for up to 10 days after an event (Allen and Duckworth 2017; O’Brient et al. 2018).

The National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan 2015 (NCDEM 2015) of New Zealand (New Zealand Government 2015a, cf. O’Brien et al. 2018) prioritises diverse communication channels and media, focusing on linguistically diverse communities and individuals with disabilities and impairments. The importance of CTIs, especially those proficient in New Zealand Sign Language, is highlighted in The Guide to the National CDEM Plan (New Zealand Government 2015b; cf. O’Brien et al. 2018). Additionally, assistance programs like the 2017 Wellington Earthquake National Initial Response Plan (New Zealand Government 2017; cf. O’Brien et al. 2018) stress the need for “accessible, clear, concise, and consistent” information. The National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan 2015 (NCDEM 2015) of New Zealand (New Zealand Government 2015a; cf. O’Brien et al. 2018) emphasises the necessity for different communication channels and media and targets linguistically diverse communities and individuals with disabilities and impairments.

In Japan, the presence of diverse nationalities highlights potential communication barriers during SAR operations. The 1961 Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act (Director General for Disaster Management Japan 1997), revised in 1997, recognises the importance of communicating with foreign residents and visitors during disasters, emphasising the need for accurate information transmission (Director General for Disaster Management Japan 1997, O’Brien et al. 2018). Japan is working on improving crisis translation strategies, with efforts including research on disaster-related automated translation applications since 2016 (Cabinet Office Government of Japan 2016; O’Brient et al. 2018). In 2017, they tested automated speech-to-speech translation technology for multilingual applications during crisis simulations (Cabinet Office Government of Japan 2017, O’Brien et al. 2018). In 2019, the Japan Meteorological Agency compiled a 'multilingual dictionary' for meteorological disasters in multiple languages (Japan Meteorological Agency 2023). However, to date, there is no smartphone application available as envisioned for translators and interpreters in crisis settings, akin to the one we are putting forth in this project.

The diverse population in the USA requires language assistance for public services. The National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care (CLAS Standards) provide a framework on communication and language assistance that emphasises principles like free language help for those with limited English proficiency and raising awareness of available language services (OMH 2023). To address linguistic needs, the US Office of Minority Health (OMH) developed online training for health professionals due to the significant number of non-English speakers in the country (OMH 2023; FEMA 2011). The US's Language Access Plan (LAP), led by Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) aims to ensure equal access to disaster assistance communications for all, regardless of language proficiency or communication needs (FEMA 2016). It was developed following events like the 9/11 attacks and Hurricane Katrina (FEMA 2016). Additionally, the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act identified priority languages for emergency response (Civil Rights Division US Dept of Justice 1964). While the LAP is the first plan to address information access during crises and distinguishes between translation and interpreting, it primarily focuses on interpreting, as noted by O'Brien et al. (2018).

Using Tomaevski's 4-A paradigm applied by O'Brien et al. (2018), it is evident that the selected five countries—Ireland, the UK, New Zealand, Japan, and the USA—only partially meet their responsibilities in providing disaster information to linguistically diverse groups. There is still much work to be done.

Regarding the European Union's (EU) disaster preparedness, the resolution No. 1313/2013/EU on the Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM) outlines the establishment of an Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) with a 24/7 operational capacity. It is responsible for coordinating, monitoring, and supporting emergency responses at the EU level, working closely with national civil protection authorities and relevant Union bodies [Art. 7 Para. 1]. However, the resolution lacks explicit mention of translators and interpreters in disaster coordination efforts, potentially leaving a gap in addressing language-related communication needs during crises (O’Brien et al. 2018).

Disaster management involves diverse disciplines, including international support teams deployed during natural disasters. Efficient communication between local communities and foreign Search and Rescue (SAR) teams is crucial for disaster management. To enhance disaster resilience, initiatives like ARÇ (Afette Rehber Çevirmen Oluşumu), the Turkish Interpreters-in-Aid at Disasters (IAD) Initiative, RESPOND: Crisis Translation or TWB (Translators Without Borders) are vital. CTIs from ARÇ actively participated in SAR operations following the February 2023 earthquakes in Turkey. Despite effective training, CTIs encountered language-related challenges during fieldwork, highlighting the need to digitise CTerm.

Organisations like ARÇ, RESPOND, or TWB are crucial in disaster response, particularly in countries with a 'high' World Risk Index ranking, including France, Greece, Italy, and Spain (BEH 2022; UNDRR 2022; UN OCHA 2022) (cf. World Map of Risk 2022). Coordinating volunteer translator and interpreter teams post-disaster can significantly enhance response and recovery efforts.

3. 2023 Turkey Earthquake

Disaster response requires the involvement of diverse professionals, including CTIs, who play a crucial role in facilitating accurate communication during and after crises. These CTIs undergo specialised training to support humanitarian aid efforts. Hence, in humanitarian emergencies where instant and precise communication is vital, having reliable terminology sources for CTIs is essential.

Turkey, highly susceptible to natural hazards like earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, droughts, and sea-level rise, faces varying levels of disaster intensity. Recent events have underscored Turkey's vulnerability, particularly to earthquakes.

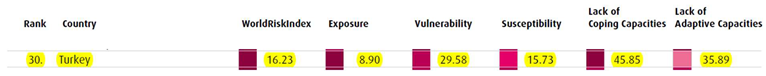

In the

World Risk Report 2022 (UNDRR 2022), Turkey ranks 30th out of 193 countries, with a score of 16.23% that considers factors such as exposure, vulnerability, susceptibility, coping capacities, and adaptive capacities (cf.

Table 1).

Table 1.

An Excerpt from the World Risk Report 2022.

Table 1.

An Excerpt from the World Risk Report 2022.

Effective communication is vital in disaster management, especially when coordinating with international SAR teams. Organisations like AP, ARÇ, and TAP facilitate this communication. For instance, ARÇ, established after the Gölcük earthquakes, operates under a protocol between the Turkish Translation Association and AFAD, the Ministry of Interior's Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (Kurultay and Bulut 2012; Doğan 2016; Kahraman 2003). Its objectives include specialised training for volunteers in translation and interpretating for crises and preparing experienced translators and interpreters for crisis deployments. Both ARÇ and TAP offer comprehensive training programs covering civil defence, first aid, disaster preparedness, communication, and interpreting practices (Kurultay and Bulut 2012; Bulut and Kurultay 2001). ARÇ's training includes a 100-hour course followed by advanced training, while TAP offers a similar program. However, despite effective training, CTIs encountered language-related challenges during fieldwork, emphasising the need for digitalising CTerm, as discussed below.

Another relevant study in Turkey is the Glossary for Terms Related to Disaster Management (Doğan and Kahraman 2011; AFAD). This glossary explains crisis terms (CTerms) in Turkish and English, focusing on disaster-related terminology for translation from Turkish to English.

The concept of creating a smartphone application as a reliable terminology resource for onsite CTIs emerged following two earthquakes in K.Maraş, Turkey, on February 6th, 2023. Around 250 CTIs were dispatched to assist 94 international SAR teams and relief organisations from over 70 countries in 11 affected towns. These CTIs supported operations in 14 languages. Additionally, international teams established fully equipped field hospitals during post-quake operations, which were later donated to local authorities after 53 days of service.

CTIs had been deployed proficient in Modern Turkish (tur) as their native language. The demand and availability of onsite CTIs can be categorised as follows:

-

1.

Obtained easily: German (deu), English (eng), French (fra), Russian (rus) and, Spanish (spa).

-

2.

Obtained with difficulty: Greek (ell), and Chinese (zho).

-

3.

Not obtainable: Japanese (jpn), Dutch (nld), Portuguese (por), and Ukrainian (ukr).

-

4.

Minority and migrant languages: Standard Arabic (arb), Levantine Arabic (apc), and Northern Kurdish/Kurmanji (kmr).

In Category 1, demands for languages like deu, eng, fra, rus, and spa were easily met due to the availability of proficient CTIs. Category 2 languages, such as ell and zho, presented challenges as few CTIs could assist. Category 3 languages, including jpn, nld, por, and ukr, could not be fulfilled, necessitating the use of English as an intermediary language. Category 4 languages, like arb, apc, and kmr, had adequate CTI support. Some situations led to a complete lack of CTI assistance, leading authorities to turn to Professional Tour Guides (PTGs) for help.

The earthquake disaster in Turkey highlighted the challenges posed by language barriers in coordinating international disaster relief efforts and communicating with affected populations. CTerm covers a wide range of subject areas, including medical sciences; emergency medicine; public health emergencies; medical device; pharmaceutical industry; nursing; mechanical engineering; public safety; safety and security; working conditions; electronics and electrical engineering; earthquake engineering/seismic or seismological terminology; civil engineering (construction terminology); geophysical engineering; disaster psychiatry; disaster law (disaster risk reduction; disaster preparedness and response; disaster recovery; international disaster response law; protection, gender, and inclusion; public health emergencies); sociology of disaster(s)/sociological disaster research; psychology of disaster; search and rescue equipment; disaster risk, crisis, and resilience management; emergency and disaster management; migration and refugees, making it difficult for CTIs to memorise all relevant terms. Thus, CTIs were provided with printed spreadsheets containing over 400 terms translated into 30 languages by ARÇ (cf. BU 2023). These lists were distributed in both physical and digital formats. However, using printed terminology lists was not practical under time constraints. Some CTIs had no access to terminological references, and PTGs lacked training in CTerm.

The CTermBank will initially focus on specific domains, including earthquake engineering/seismic or seismological terminology, emergency medicine, civil engineering (construction terminology), and search and rescue equipment. This emphasis is due to the devastating impact of earthquakes, which are among the deadliest natural disasters, often leading to cascading events like structural collapse, avalanches, landslides, tsunamis, and fires. Managing the aftermath of earthquakes, particularly structural collapse operations, is highly intensive and typically requires a team of at least four or five specialists, as outlined in the INSARAG Guidelines for 2020 Vol. II: Preparedness and Response – Manual A: Capacity Building.

When three days after the earthquake, portable Wi-Fi systems were introduced to provide internet access, CTIs availed themselves of a trio of online tools to contend with the intricacies of terminology during crisis response:

-

1.

Tureng: CTIs initially consulted Tureng, a general-purpose multilingual dictionary, as a preliminary reference. However, Tureng lacked definitions and contextual information, offering only a list of Turkish equivalents for Source Language (SL) terms. If CTIs felt that Tureng's output did not provide a suitable Turkish equivalent, they proceeded to further searches.

-

2.

Google: CTIs turned to Google as a web browser when Tureng's results were insufficient or when no results were found. Google searches were used to verify or complement information obtained from Tureng, particularly if Tureng did not generate any output.

-

3.

Google Images: In cases where Google searches failed to produce satisfactory Turkish equivalents, CTIs resorted to Google Images. This allowed CTIs to visually represent search terms, aiding in conveying their meanings, especially for language for specific purposes (LSP) that could not easily be translated into language for general purposes (LGP) equivalents. Visual aids played a crucial role in overcoming language barriers during crisis communication.

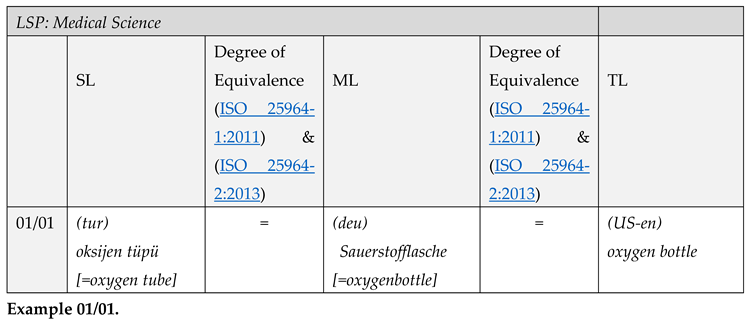

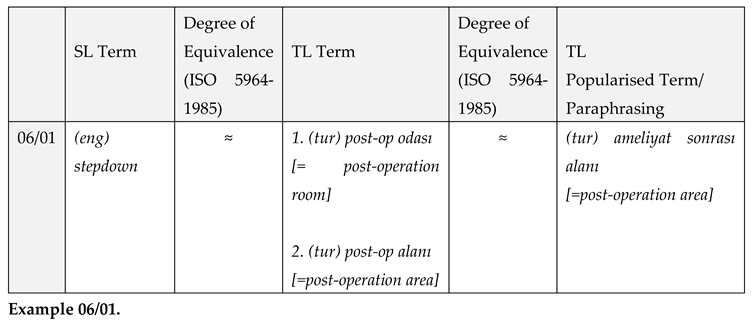

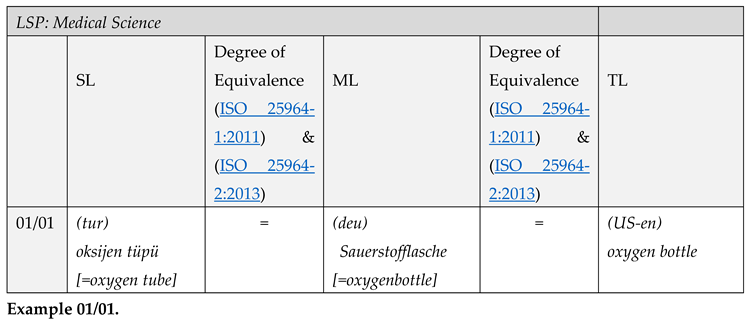

A multilingual

CInt, proficient in

tur as the native language,

deu as the second native language, and

eng as a foreign language, proposed a

Mediating Language (

ML) approach. This solution aimed to bridge the terminology gap between (

tur)

oksijen tüpü (for (

eng) oxygen tube) and its

deu counterpart

Sauerstofflasche, ultimately resulting in the

US-eng term

oxygen bottle (cf.

Example 01/01).

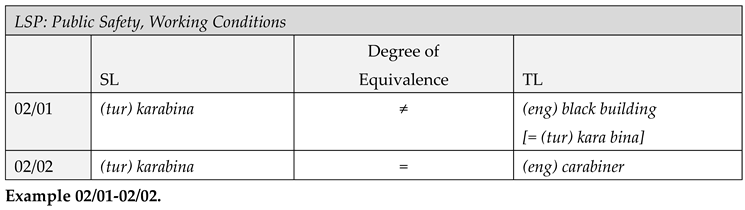

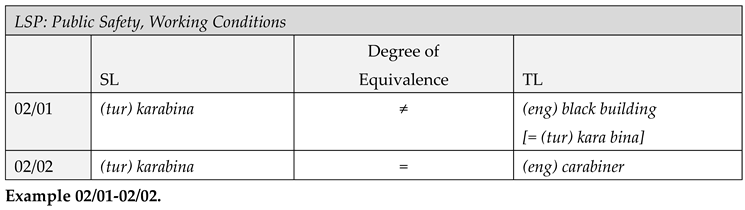

During a rescue operation, a CInt erroneously interpreted the term (tur) karabina as (eng) black building (cf. Example 02/01), instead of the correct interpretation (eng) carabiner (cf. Example 02/02). This misunderstanding resulted from the CInt's unfamiliarity with the term, causing them to perceive it as two distinct tur LGP elements.

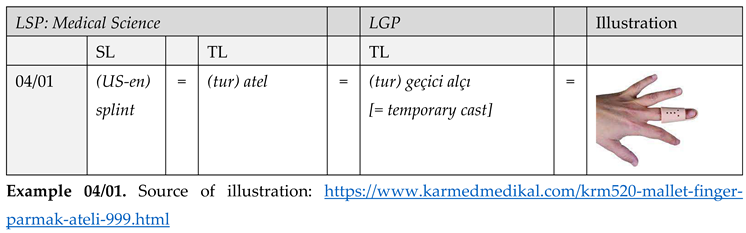

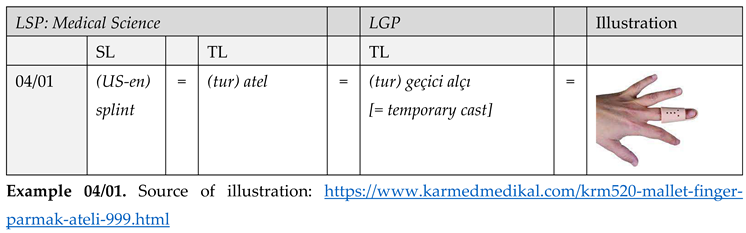

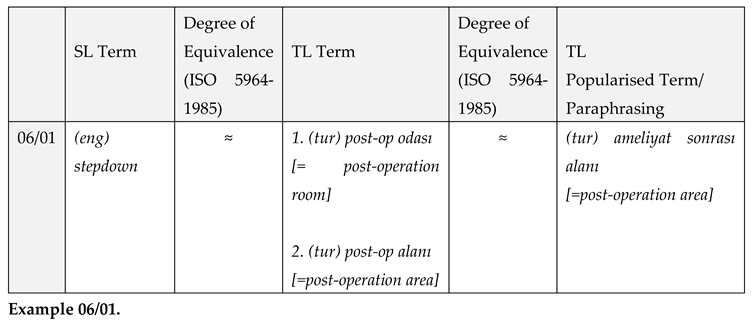

In a medical context, a Turkish patient struggled to understand the term (tur) atel, equivalent to (US-en) splint. The CInt provided an alternative LGP interpretation, (tur) geçici alçı (translated to (eng) temporary cast), but it remained unclear to the patient. To enhance understanding, the CInt used Google Images to visually represent the term (cf. Example 04/01). This incident highlights the limitations of commonly used terms and underscores the importance of visual aids in resolving ambiguity. Broadening end-user involvement could make such terms more accessible, benefiting not only patients in field hospitals but also immigrants and refugees (cf. CLEAR Global 2023), as needed.

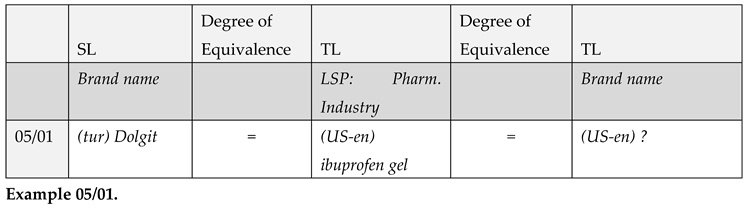

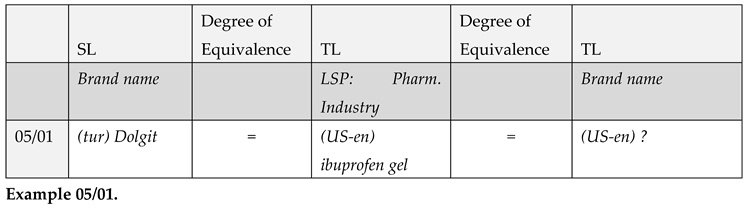

In a brand name-related scenario, a Turkish patient in a field hospital requested a medication known as Dolgit, which the American doctor was unfamiliar with. To resolve this, the CInt used their smartphone to find information about the medication online. The search revealed that Dolgit contained "ibuprofen (ibuprofenum) 5 g in an oil-in-water emulsion in 50 g or 100 g of cream and excipients," a pain relief substance produced by the German company Dolorgiet GmbH and commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry. Armed with this knowledge, the doctor could then provide the patient with an equivalent medication available in the US (cf. Example 05/01).

The above points and practical experience highlight the necessity for a multilingual smartphone application to facilitate efficient communication for CTIs during crises. Building upon this insight, we will propose essential design elements for such an application in crisis settings.

4. Product Features

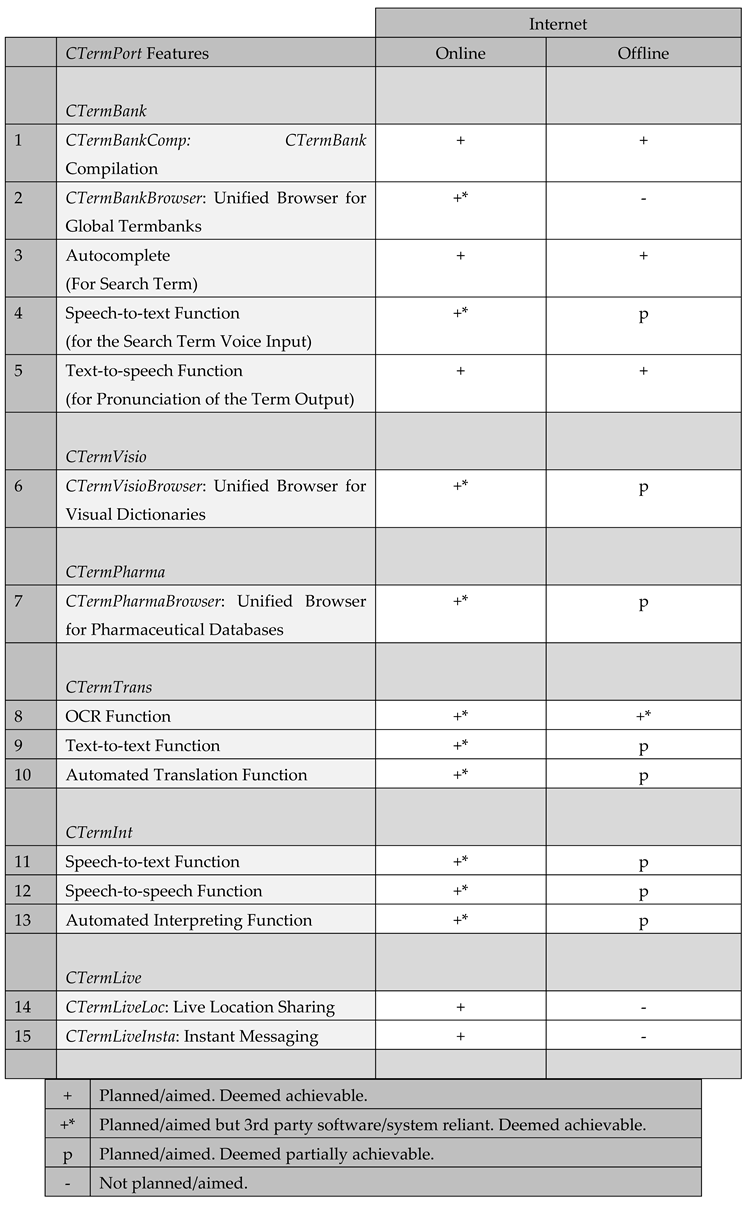

Table 2 categorises all the features within the

CTermPort as online (+) or offline (-) functions. While consolidating all the features within a single application is the simpler approach, the features might be divided to separate applications for online and offline scenarios as well. Especially, a mobile application native to relevant devices designed for offline scenarios may be plausible to achieve maximum reachability, usability, and performance, while maintaining a secondary web application to provide the online features.

Table 2.

CTermPort Features.

Table 2.

CTermPort Features.

4.1. General Features of the Master-Application

The CTermPort should encompass the following fundamental features:

-

1.

Reachability: It should be readily downloadable as a free application either from its official website or alternative mirror sites. Mirror sites, in themselves, are legitimate copies created for various reasons, such as distributing content more efficiently, reducing server load, or providing redundancy, i.e. creating additional copies of the same content on different servers or locations. This redundancy serves as a backup or failover mechanism. If one server or site experiences issues, users can still access the content from another server or site, ensuring continued availability and reducing the risk of service disruptions. Moreover, availability through online stores is advisable as an additional means of access.

-

2.

Offline Capability: The application must offer an offline mode, granting users access to a curated subset of essential terminology resources even without an active internet connection.

-

3.

Online Connectivity: When internet access is available, the application should seamlessly connect to existing termbanks online, ensuring access to up-to-date terminology resources.

During a crisis, an electricity blackout can disrupt internet connectivity. Therefore, it is vital for the CTermPort software to include offline functionality, ensuring that essential terminology resources remain accessible even without an internet connection.

When power is restored, portable Wi-Fi devices become crucial. They enable the application to switch to online mode, allowing it to access the latest terminology content from online termbanks. This dual-mode operation ensures that the CTermPort remains useful and up-to-date during crises.

The comprehensive CTermBank collection should encompass the following advanced features to enhance usability and accessibility:

-

1.

Language Selection: Users should have the capability to select both the SL and TLs to cater to their specific linguistic needs.

-

2.

Search Functionality: The application must incorporate a user-friendly search button, enabling efficient entry of the desired term, both for searching the CTerm collection as well as browsing global termbanks.

-

3.

Auto-Complete Search: To expedite searches, particularly in offline mode, an auto-complete search feature should be integrated, allowing users to swiftly find relevant terms.

-

4.

Speech-to-Text Integration: When online, the application should offer a speech-to-text feature, permitting users to initiate searches by verbally stating the source term. This functionality enhances accessibility and convenience. Additionally, the same functionality can be employed in the context of automated translation.

-

5.

Text-to-Speech Capability: To aid in pronunciation and comprehension, the application should include a text-to-speech feature, enabling the vocalization of target terms. Additionally, it may provide transcriptions of target terms according to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) system for linguistic clarity and precision.

The CTermBank should cover the following key properties:

-

1.

Accessibility and ease-of-use: Accessibility and ease-of-use are crucial aspects of an application that ensure a positive user experience for all individuals, regardless of their abilities or technical proficiency. An accessible application is designed to accommodate users with disabilities, ensuring that everyone, regardless of their abilities, can use the app effectively. This includes considerations for visual, auditory, motor, cognitive, and other impairments. Incorporates features like screen readers, alternative text for images, keyboard navigation, voice commands, and adjustable settings (like text size and colour contrast) to assist users with disabilities. On the other hand, the application boasts a user-friendly interface that's easy to understand and navigate, even without prior instructions. It utilises clear menus, icons, and layout to guide users seamlessly through the app. Maintains consistency, which helps users understand patterns to use the app more efficiently, in design elements, terminology, and functionality across different sections or screens within the app. We collaborate to integrate these aspects into the application during its design and development stages. End-user testing, feedback collection, and iterative improvements are key to refining both accessibility and ease-of-use continually. A well-executed balance between these aspects results in an application that's not only accessible but also user-friendly for a broader audience.

-

2.

Being lightweight: To be “lightweight” for an application, it typically means that it has been designed and developed to have a small file size, minimal resource usage (such as CPU, memory, and storage), and low system requirements. A lightweight application has a compact size, occupying minimal storage space on the device. Also, the application consumes less CPU power, memory (RAM), and battery life compared to larger or resource-intensive apps. It does not strain the device's hardware, making it suitable for older or less powerful devices. Lightweight applications typically load quickly and run smoothly. They have faster startup times, respond promptly to user interactions, and deliver a seamless user experience without lags or delays. They focus on essential functionalities, providing core features without unnecessary complexity. We achieve lightweight application through various optimisation techniques, including code optimisation, resource compression, modular architecture, and efficient use of APIs and libraries. Striking a balance between functionality and resource consumption is crucial to ensure the app remains lightweight while offering valuable features to users. Ultimately, we aim to a lightweight application to provide a functional, responsive, and efficient user experience without burdening the user's device with unnecessary overhead.

-

3.

Reliability: Reliability in the context of an application refers to its ability to consistently perform and deliver its intended functionalities without failure or unexpected issues. reliable application should exhibit several key characteristics: Stability, Consistency, Availability, Robustness, Performance, Security, Scalability. Achieving reliability requires a robust development process, including thorough testing, quality assurance, and ongoing maintenance. Continuous monitoring and feedback from users help identify and address potential issues, allowing us to improve the application's reliability over time.

Visual dictionaries offer CTIs a valuable resource for visualising terms and concepts. Here are several online visual dictionaries:

-

1.

Ikonet

-

2.

Merriam-Webster Visual Dictionary Online

-

3.

The Visual Dictionary

These visual dictionaries can enhance clarity and accuracy in CTI communication during crisis situations, providing visual references for complex terms.

In the realm of pharmaceutical information, a plethora of databases stands as valuable resources, serving as essential tools not only for qualified communicators like CTIs but also for experts within the medical field, including paramedics, medical doctors, and nurses. These databases facilitate the search for equivalents and analogues of specific pharmaceuticals, ensuring the provision of accurate and reliable information. Some notable pharmaceutical databases of significance include:

-

1.

API-Data.com

-

2.

DrugBank Online

-

3.

Drugdatabase Online

-

4.

Drugs.com

-

5.

European Medicines Agency

-

6.

Heads of Medicines Agencies

-

7.

Pill in Trip: Drugs around the World

-

8.

RP Resource Pharm

-

9.

WHO

These comprehensive databases serve as authoritative sources for accessing trustworthy health information, enabling communicators and medical professionals alike to navigate the intricacies of pharmaceutical terminology and pharmaceutical equivalencies effectively, particularly in high-stress and time-sensitive crisis situations.

To optimise ATI tool effectiveness in crises, an integrated CTermBank database is vital, forming the foundation for optimal performance. ATI tools provide adaptable solutions for diverse communication needs across all crisis phases, from immediate response to preparedness, recovery, and community development. This proactive approach aligns with the literature emphasising translation and interpreting as risk reduction tools, preserving language rights and linguistic equality (Federici 2022).

Incorporating the following features into the CTermPort software is imperative for CTIs:

-

1.

CTermTrans: Integration of an Optical Character Recognition (OCR) capability to scan both handwritten and typed documents. This function serves as the foundation for the text-to-text and text-to-speech machine translation processes.

-

2.

CTermInt: Inclusion of a speech-to-speech feature, enabling immediate machine interpreting output to enhance real-time communication.

In time-sensitive situations, interpreting plays a vital role, as emphasised by O’Brien (2022). Despite its significance, CIing has historically received limited attention, except in contexts such as conflicts, military operations, refugee assistance, peacekeeping (evident in Gaunt 2016, Moreno-Bello 2021; Ruiz Rozendo 2020; Todorova 2020; Valero Garces 2022), healthcare (as discussed in Ng and Ineke 2020), and law enforcement (noted in Del Pozo Trivino 2020; Drugan 2020). It is important to note that the phases of a crisis go beyond the response stage and often blur the boundaries between translation and interpreting. This means that CInts may also need to translate, and vice versa, highlighting the essential and complementary role of interpreting in crisis management, while acknowledging the complementary function of translation (O’Brien 2022).

The 2023 Turkish earthquake revealed situations where SAR teams faced challenges due to language gaps or insufficient CInt numbers. Consequently, there is an urgent need for the development or integration of a speech-to-speech automated interpreting system. This system, whether based on neural, statistical, or hybrid approaches, should be coupled with the extensive multilingual CTermBank compilation. By doing so, it will markedly improve communication in diverse linguistic crisis scenarios.

CTermLive will introduce two key components to support CTIs during crisis situations:

-

1.

Live Location Sharing: To support logistical coordination and enhance CTIs' collaboration, an optional feature for live location sharing will be incorporated. CTIs can use this feature to identify the real-time locations of fellow team members. This aids in maintaining situational awareness and coordinating efforts effectively. It also ensures that individuals are aware of each other's positions and can quickly request assistance or provide it as needed. It allows for the allocation of tasks based on geographical proximity and ensures that resources are deployed optimally.

-

2.

Instant Messaging: This component of CTermLive will provide CTIs with a real-time instant messaging platform, enabling efficient communication and information exchange during crisis situations. It serves as an additional tool to enhance collaboration and ensure effective crisis response. This component facilitates real-time communication between team members, supporting them in making informed decisions and adapting their response strategies based on the evolving situation.

Both features should be active exclusively when an internet connection is present.

In conclusion, the discussion underscores the critical role of CTermPort and its associated tools in facilitating effective communication during crises. It highlights the necessity for comprehensive and consolidated terminology resources (CTermBank) with offline accessibility and inclusivity for vulnerable populations. Additionally, the integration of visual dictionaries (CTermVisio), pharmaceutical databases (CTermPharma), automated translation and interpreting tools (CTermTrans and CTermInt), as well as a live location sharing option and instant messaging (CTermLive), are crucial for enhancing language support and communication in multilingual crisis settings. These efforts ultimately contribute to more efficient crisis management and response.

4.2. Additional Features as Alternative Communication Systems

In parallel, considering the distinct needs of vulnerable citizens (VulCs), including individuals with disabilities or impairments, requires the incorporation of alternative features within the CTermPort to ensure inclusivity:

-

1.

Ideally an embossed screen protective film designed for smartphones, featuring tactile blisters reminiscent of the Braille transcription system, can be affixed to smartphone screens, enabling the visually impaired to easily detect icons and navigate the interface.

-

2.

A read-aloud or talk-back feature, which serves as a graphics-to-speech function. This feature benefits the visually impaired by providing audio feedback on selected icons when interacting with the embossed screen protective film. Moreover, the applications’ speech-text-speech function enables the visually impaired to vocally request a term and receive the response audibly.

-

3.

The existing read-aloud or talk-back feature in smartphones, designed for the visually impaired by converting graphics into speech, provides audio cues for selected icons during interactions. With this project, the proposed speech-to-text-to-speech function aims to enable the visually impaired to verbally request a term and receive an audible response.

-

4.

Implementation of a speech-to-text feature, primarily intended for the hearing impaired. This functionality converts spoken language into written text, facilitating effective interaction, such as when searching for terms, to ensure accessibility.

In summation, the seamless integration of technological advancements, the development of a robust CTerm databank, and the consideration of features catering to individual characteristics, especially among VulCs, collectively form a comprehensive approach to enhance communication and inclusivity within the realm of crisis management.

5. The Design of the CTermPort for Crisis Settings

The above points and practical experience highlight the necessity for a multilingual smartphone application to facilitate efficient communication for CTIs during crises. Building upon this insight, we will propose essential design elements for such an application in crisis settings.

5.1. Materials and Methodology

Alexander and Pescaroli (2020) identified key considerations for effective crisis communication (cf. Herrick and Morrison 2010; Miller and Pescaroli 2018):

-

1.

Determine essential terminology for clear, concise, and neutral messages.

-

2.

Utilise the local context of language to enhance explanations.

-

3.

Address the needs of vulnerable populations like the elderly and those with disabilities.

-

4.

Assess the suitability of communication tools for various scenarios like power outages.

-

5.

Ensure effective communication with language-diverse communities.

These considerations form a robust framework for crisis communication strategies. Incorporating the insights of Alexander and Pescaroli (2020), we will adapt and customise these principles to align with the specific requirements of CTIs.

5.2. Objectives

The objective is to create a comprehensive solution comprising a downloadable offline Crisis Terminology Application (CTermApp) for smartphones. It will feature an integrated search function that links to existing terminological databases when online. Additionally, speech-to-text automatic translation (CTermTrans) for CTs and speech-to-speech automatic interpreting (CTermInt) systems should be integrated to assist both experts and laypersons without CTI support. These enhancements will complement the multilingual CTerm collection (CTermBank). Furthermore, a live location-sharing (CTermLive) feature is vital for effective CTI coordination.

To initiate the CTermApp project effectively, it should prioritise the following aspects:

-

1.

Terminology: Gather commonly used terms, especially within emergency medicine, civil engineering (construction terminology), and search and rescue equipment.

-

2.

Languages: Focus on languages falling within Categories 1, 2, and 3, as these are the main languages in demand for CTerm. The current inadequacy of CTerm in terms of volume and accessibility necessitates harmonisation and augmentation efforts.

Prioritizing CTerm entails gathering the most frequently used basic terms from relevant subdomains, with room for expanding the CTermBank in future projects. Initially, the collection target for each subdomain should be around 400 terms for optimal effectiveness. The integration of Category 1, 2, and 3 languages, including deu, eng, fra, rus, spa, ell, zho, jpn, nld, por, ukr, and tur, into a unified compilation is crucial for improving SAR operations.

Furthermore, considering the potential challenges faced by both local and international disaster relief teams when communicating with communities lacking proficiency in the local language, it is advisable to contemplate the inclusion of Category 4 languages, i.e., minority and migrant languages, in the future CTermBank compilation, possibly as a separate smartphone application (e.g. CTermMiL), to address specific demographic needs.

5.3. Linguistic Approach

The linguistic approach involves providing standardised data but may also include non-standardised information with quality ratings (Rondeau 1983), as mentioned in (Cabré 1999).

5.4. Nature of Data

The nature of data includes the following criteria (Rondeau 1983; cf. (Cabré 1999):

-

1.

Terminological

-

2.

Translation-based

-

3.

Grammatical (syntactic, orthographic)

-

4.

Encyclopaedic

-

5.

Lexical from general language (LGP) (concerning popularised terms)

-

6.

Non-linguistic/Visual (e.g. illustrations)

5.5. Organisation of Data

The organisation of data should consist of multilingual records, which are concept-based (Rondeau 1983; cf. Cabré 1999).

5.6. Existing Terminology Resources

5.6.1. Termbanks

Existing termbanks listed below serve as a valuable initial resource for accessing crisis terminology when online. The proposed feature involves incorporating existing termbanks with an API (Application Programming Interface) into the developing CTermBank collection. This integration will offer CInts the ability to explore various termbanks through a unified browser. When a search term is entered, the browser will generate a list of termbanks containing the specified term in their collection, streamlining the search process with a single query:

-

1.

CERCATERM

-

2.

DIN-TERMinologyPortal

-

3.

Eurotermbank

-

4.

IATE

-

5.

TEPATermbank

-

6.

TermCat

-

7.

TERMIUMPlus

-

8.

UNBIS

-

9.

UNTERM

-

10.

WIPO Pearl – Multilingual Terminology Portal

5.6.2. Other Terminology Collections

Terminology collections other than termbanks comprise dictionaries, glossaries, thesauri, and vocabularies from organisations like AFAD, Bosphorus University, CLEAR Global - Translators Without Borders (TWB), FEMA, İstanbul Fire Brigade, OIEWG, TDK/TLI-The Turkish Language Institute, TriMED, UNDRR, UNHCR, UNISDR, WHO, among other sources, serve as valuable sources for compiling the CTermBank:

-

1.

-

AFAD Glossary of Disaster Management Terminology

-

2.

-

Bosphorus University, Department of Translation and Interpreting Studies, Terminology for Search & Rescue and Disaster Management

-

3.

-

CLEAR Global - Translators Without Borders (TWB)

-

4.

EU Knowledge Centre on Interpretation – EU Terminology Sources

-

5.

EUROVoc – EU Vocabularies

-

6.

-

FEMA

-

7.

İstanbul Fire Brigade

-

8.

OIEWG – Open-ended Intergovernmental Expert Working Group on Indicators and Terminology

-

9.

TDK/TLI – The Turkish Language Institute Dictionaries

-

10.

TermCat

-

11.

TERMINOTRAD

-

12.

TriMED

-

13.

UNDRR – UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction – Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction

-

14.

UNDRR – Prevention Web - Terminology On Disaster Risk Reduction

-

15.

UNHCR – The UN Refugee Agency – Master Glossary of Terms

-

16.

UNISDR (2009) Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction

-

17.

WHO

-

18.

WIPO

Two potential sources can significantly contribute to the development of the CTermBank collection:

-

1.

TDKTurkish Language Institute App: The TDK offers a free smartphone application called TDK Türkçe Sözlük, which includes dictionaries and glossaries. This app prioritises user privacy and does not collect personal information.

-

2.

-

TriMED Multilingual Terminological Database: TriMED is a unique multilingual terminological database designed to address challenges in medical terminology. It covers English, French, and Italian languages and serves three user categories (Vezzani et al. 2018):

-

a.

Doctors can utilise TriMED to cross-reference with other medical resources like MeSH terms and Snomed CT.

-

b.

Patients have access to the equivalents of medical terms in common usage, including popularised terms.

-

c.

Translators and/or interpreters can consult terminology records to gather information in both the Source Language (SL) and Target Language (TL).

TriMED offers valuable resources for popularised medical terminology (cf. Akçiçek and Karaman 2014; Karaman 2015b) and can contribute significantly to the CTermBank collection.

5.6.3. Texts

Numerous electronic texts are available as sources for extracting relevant CTerm. Retrieving monolingual, as well as comparative and parallel texts from online resources ensures access to up-to-date specialised terminology. Compiling a corpus of SL texts, including:

-

1.

Textbooks, handbooks, scientific books, academic articles, research reports

-

2.

Guidelines, technical manuals, patents, technical specifications

-

3.

Dissertations, theses

-

4.

Special dictionaries, thesauri, glossaries, nomenclatures, etc.

-

5.

Standardised vocabularies

Files and other storage media (e.g. technical specifications, patents, government publications, industry reports, etc.)

offer authentic examples of LSP usage (Karaman 2018). These texts, authored by reputable sources and subject field experts, serve as reliable resources for building a comprehensive CTerm repository.

Texts can be retrieved from the following repositories:

-

1.

ECLAC Library

-

2.

EDRIS The European Emergency Disaster Response Information System

-

3.

INFORM Global Open-Source Index for Risk Management

-

4.

IRIS WHO Institutional Repository

-

5.

UN Digital Library

-

6.

UNEP Knowledge Repository etc.

In multiple consortium meetings, a consensus was reached to initiate the project by gathering English texts as the Source Text (ST) from specific domains, including civil engineering (construction), emergency medicine, and search and rescue equipment. The focus will be on extracting terms commonly used in post-earthquake settings during response times. Once 400 terms are extracted in English, the next step involves terminology work for finding the corresponding equivalents in the relevant Target Languages (TLs) (Category 1, 2, 3 languages). Subsequently, the translation of these terms into their TL equivalents will pave the way for populating the data categories, utilising a software for the compilation of term records (e.g. FAIRterm, MultiTerm, termweb4, etc.).

5.6.4. Term Extraction Tools

In the realm of terminology extraction, a multitude of tools have emerged to facilitate this intricate process. Notable resources, such as the European Language Grid (ELG), a comprehensive platform encompassing a spectrum of European language technologies, Terminotix, a dedicated hub offering information on tools catering to computer-assisted translation requirements, and others including CLARIN, and LLOD, stand as valuable repositories for individuals seeking term extraction solutions. A straightforward inquiry, involving the search term "term extraction", yields a reservoir of potential tools primed for the extraction of terms from pertinent texts. These tools exhibit a range of capabilities, accommodating both language-dependent and language-independent terminological endeavours.

Here, we present a selection of open-source term extraction tools that hold promise in this domain:

-

1.

DPS (Dictionary Publishing System)

-

2.

ELEX Project

-

3.

Germinal

-

4.

LinguaKit

-

5.

Sketch Engine

-

6.

SpaCy

-

7.

SynchroTerm

-

8.

TaaS: Bilingual Term Extraction System

-

9.

TerMine

-

10.

Terminotix

-

11.

TermoPL

-

12.

TermoStat

-

13.

TermSuite

-

14.

TExSIS (Term Extraction Software Simple & Intuitive System)

-

15.

Text2TCS: automatically extracts conceptual systems from texts.

These tools cater to various aspects of terminology extraction, management, and linguistic analysis, offering valuable resources for language professionals and researchers in the field of language technology.

6. The Design Steps

6.1. Database Records and Data Categories of the CTermBank Collection

In alignment with the principles governing the construction of termbanks, the development of the CTerm collection necessitates adherence to a meticulously structured tripartite process, encompassing the following key stages:

-

1.

Compilation: This process involves the identification, sourcing, and extraction of relevant terms, drawing from an array of authoritative linguistic resources and subject matter experts. The goal is to gather an extensive corpus of crisis-related terminology, encompassing a diversity of domains and languages, while prioritising the most frequently employed terms and expressions.

-

2.

Storage: This stage entails the establishment of a structured and accessible repository that can effectively accommodate the extensive multilingual terminological assets. Specialised database management systems are employed to ensure the secure and systematic storage of terminological entries, including detailed definitions, contextual usage, and cross-lingual equivalents. The storage infrastructure is designed to facilitate efficient data retrieval and utilisation, both in online and offline contexts.

-

3.

Retrieval: The retrieval stage includes the design of search functionalities, query capabilities, and navigation aids that enable rapid and precise access to terminological data. Furthermore, it accommodates features for real-time, context-specific retrieval, catering to the dynamic requirements of crisis management scenarios.

Firstly, in the initial phase of the compilation process, several pivotal decisions must be made to align with the overarching design and feasibility of the terminological collection, as delineated in established terminological principles (Cabré 1999). These decisions encompass three fundamental facets that lay the groundwork for the subsequent development of the CTermBank collection (Cabré 1999):

-

1.

-

Source Material Considerations: The compilation process commences with the selection of source material, recognising that the foundation of terminological assets is rooted in textual content. Several critical determinations are essential within this domain:

-

a.

Nature of the Material: Careful consideration is given to the thematic relevance of the material, specifying the subject matter that pertains to crisis scenarios. Additionally, the choice extends to the type of texts that should be included, taking into account the appropriateness of different textual genres and content types.

-

b.

Material Location: The precise whereabouts of the source material are identified, along with the format in which it is accessible. This entails cataloguing the physical or digital repositories where the textual content resides.

-

c.

Extraction Methodology: The methodology for extracting terminological entries from the selected texts is defined. This includes delineating the step-by-step process to transition from comprehensive texts to individual terms, along with the initial information associated with each term.

-

d.

Text Selection Criteria: Criteria for the selection of texts are established, encompassing descriptions of text attributes, protocols for utilising these descriptions, and comprehensive manuals elucidating the criteria for assessing the suitability of textual materials.

-

e.

Compilation Process Organisation: The overall organisation of the compilation process is carefully structured, encompassing considerations such as workforce allocation, priority setting, task identification, and task delegation.

-

2.

-

Extraction Record Content: An integral aspect of the compilation process pertains to the extraction of pertinent information from texts, which subsequently forms the basis for the creation of extraction records. This information includes:

-

a.

Term Description: A comprehensive description of each term encountered in the source texts is recorded, along with the contextual information that provides insights into the term's usage.

-

b.

Reference Information: For each term, reference information is meticulously documented to enable cross-referencing and traceability. This reference information includes details pertaining to the source text, facilitating easy retrieval and validation.

-

c.

Protocols for Use: Protocols and guidelines are established for the effective utilisation of extraction records, ensuring uniformity and consistency in their application.

-

3.

-

Term Record Information: Furthermore, the identification and extraction processes extend to the assembly of term records according to ISO 16642:2017 (Terminological Markup Framework). Some of these records encompass:

-

a.

Information Description: A detailed account of the information content to be included in the term records is outlined. This involves specifying the data to be encapsulated, the sources for augmenting extraction information, the representation format for each element, and the criteria for assessing the quality and accuracy of the information.

-

b.

Work Procedures: Clear and standardised work procedures are defined for the identification and extraction phases, ensuring methodical and systematic execution.

The culmination of these deliberations and actions ends in the creation of comprehensive term records, which serve as the foundational building blocks of the CTermBank. These records are instrumental in facilitating effective communication and linguistic support in crisis management scenarios, underscoring the significance of a rigorous and well-structured compilation process.

Secondly, the storage phase of the terminological compilation process entails the meticulous organisation of extracted terms into structured database records, sourced from a diverse array of comparable and/or parallel texts that contain pertinent information about each entry. These database records are characterised by multiple fields, each designated to house distinct data categories. In line with established database conventions, these fields are typically endowed with specific field names for clear identification and differentiation. Terms, originating from the source texts, are amalgamated into these database entries, where comprehensive information pertaining to each term is systematically documented. These entries collectively constitute a repository of essential terminological data, and the structure of these records adheres to recognised terminological standards and principles (Cabré 1999; Karaman 2018; Sager 1990; Wright 1996).

The central component of a database record is the entry or entry term, commonly denoted as the headword. It represents the full and unaltered form of the term as extracted from domain-specific texts, preserving its grammatical correctness and alignment with accepted dictionary conventions. In concept-oriented termbanks, the headword may be preceded by the concept's definition, with associated terms grouped accordingly. This organisational approach necessitates nuanced decisions regarding term prioritisation, sequence, and potential designations of synonyms. Entries encompass a diverse range of terminological entities, which can be categorised into three distinct types:

-

a.

Simple, compound, or complex terms.

-

b.

Phrases.

-

c.

Sentences (While ISO 1087:2019 and ISO 704:2022 affirm that a term corresponds to a single concept, there are scenarios, especially in languages like agglutinative versus inflecting, where a single term may encapsulate a concept paraphrased as a sentence in another language).

The entry or entry term serves as the foundational element around which the remaining fields are structured, embodying the core term extracted from Source Texts (STs). Its grammatical precision and contextual appropriateness are essential for ensuring the accuracy and utility of the compiled CTermBank collection. The categorisation of terms into the aforementioned types facilitates a comprehensive representation of terminological diversity within the database records, accommodating simple lexical units as well as more intricate and context-rich linguistic constructs.

The last stage of the CTermBank collection process focuses on retrieval mechanisms. Here, the goal is to create user-friendly tools and interfaces that empower CTIs to access and use the stored terminology effectively. This stage involves designing search functions, query capabilities, and navigation aids for quick and accurate access to terminological data. Additionally, it includes features for real-time, context-specific retrieval to meet the dynamic needs of crisis management scenarios.

The structured progression through these three stages ensures the systematic construction and efficient utilisation of the CTermBank collection, equipping CTIs and other stakeholders with a robust linguistic resource to navigate the intricate linguistic challenges encountered during crises, ultimately contributing to effective communication and response efforts.

This systematic structuring of database records, marked by meticulous attention to detail and adherence to recognised terminological principles, forms the bedrock of the CTermBank compilation, ultimately contributing to the provision of precise and reliable terminological support in crisis management scenarios.

The structuring of database records within terminological collections encompasses a multifaceted array of fields or data categories, each meticulously tailored to fulfil specific roles in ensuring the precision and comprehensiveness of the terminological content. These fields, defined in accordance with established terminological practices (Sager 1990), collectively constitute a comprehensive record that serves as a valuable resource in crisis management and communication scenarios. The following delineates these key fields or blocks of fields:

-

a.

The Information Source: This field serves as a coded representation of the origin or source of the terminological information. It aids in tracking the provenance of the data, allowing users to discern the contextual context of each term.

-

b.

Semantic/Conceptual Data: This field encompasses a rich array of semantic and conceptual information related to the term. It includes essential details such as the term's definition, its association with specific subject fields, indications of its applicability in various domains, and cross-references to related concepts. Additionally, this field may denote the sense-type of the term, providing valuable insights into its nuanced meanings and usage contexts.

-

c.

Linguistic Data: The linguistic data category encapsulates crucial linguistic attributes of the term. This includes information regarding the term's part of speech, facilitating its grammatical categorisation. It also specifies the language in which the term is recorded, adhering to ISO language and regional codes. Audio recording of pronunciation, variants of the term (including parallel data categories to the entry term), compression of existing LSP forms, full synonyms, and other sense types and their relations are meticulously documented. These synonyms, varying in their usage, context, and occasionally subject field, are considered as viable substitutes for the entry term, enhancing the terminological scope. Additionally, this category encompasses collocational information, shedding light on the typical word associations and co-occurrences involving the term.

-

d.

Non-linguistic Data: Inclusion of non-linguistic elements enriches the terminological database by incorporating visual aids and graphical representations. This category accommodates illustrations, drawings, symbols, graphics, charts, and other visual assets that enhance the user's understanding of the term, particularly when dealing with complex or specialised concepts.

-

e.

Pragmatic, Normative, and Sociolinguistic Data: The pragmatic and sociolinguistic dimension is covered within this field, offering valuable insights into the term's contextual usage. It includes information on the term's collocational patterns, usage notes, quality labels that indicate the correctness and reliability of the term, field of usage, connotations associated with the term, deprecated forms, and other sociolinguistic nuances.

-

f.

Equivalents in Other Languages: This field is pivotal for facilitating cross-linguistic understanding and communication. Initially, it focuses on Category 1, 2, and 3 languages, encompassing terms that are equivalent to the entry term in multiple languages. As the terminological collection expands, future projects may extend coverage to additional languages, broadening the scope of multilingual support.

-

g.

Administrative Data: The administrative data category encompasses essential metadata associated with the database record. It includes information regarding the author of the record, recording date, any subsequent changes made, and justifications for modifications. This administrative metadata aids in maintaining the accuracy and reliability of the terminological content while providing valuable insights into its history and evolution.

In sum, the meticulous structuring of database records into these distinct fields ensures that the CTermBank collection is a robust and comprehensive resource, tailored to the diverse needs of crisis management and communication. These fields collectively contribute to the precision, clarity, and usability of the terminological data, ultimately enhancing its effectiveness in multilingual crisis settings.

In conjunction with the core database records, a comprehensive termbank typically incorporates ancillary files that play a crucial role in organising, contextualising, and managing the terminological content. These ancillary files, comprising distinct data categories, contribute to the overall structure and functionality of the termbank. The following outlines these fundamental ancillary files:

-

1.

Term File: The term file serves as the cornerstone of the termbank, housing the primary entries or terms that constitute the core of the terminological collection. These terms are presented in their grammatically appropriate form and are meticulously linked to the corresponding database records. The term file is the principal point of reference for users seeking to access and comprehend the terminology.

-

2.

Source File: The source file functions as a vital reference, cataloguing the origins and sources of the terminological information. Each term is associated with specific source materials or texts, providing users with valuable insights into the contextual context of the term's usage and its provenance.

-

3.

Subject Field File: The subject field file categorises terms into specific subject fields or domains, offering a structured taxonomy that aids in the organisation and retrieval of terminological data. This categorisation ensures that terms are aligned with relevant domains, facilitating their use in specialised contexts.

-

4.

Grammatical Category File: This file classifies terms based on their grammatical attributes, including their part of speech. By categorising terms according to their linguistic characteristics, this file enhances the user's ability to navigate and employ the terminology effectively.

-

5.

Status Label File: The status label file plays a pivotal role in indicating the quality and reliability of each term. It includes labels or markers that denote the correctness and validity of the term, ensuring that users can make informed decisions regarding its usage.

-

6.

Author File: The author file contains essential metadata related to the authors or contributors responsible for creating and maintaining the terminological content. It records information such as the author's identity and the dates of record creation and modification. This administrative data serves as a valuable reference for maintaining the integrity and credibility of the termbank.

These ancillary files, in conjunction with the core database records, constitute a comprehensive termbank that is not only rich in terminological content but also meticulously organised and structured to meet the diverse needs of users. They play a critical role in ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and usability of the terminological data, ultimately enhancing its utility in various linguistic and subject-specific contexts.

The comprehensive compilation of CTermBank necessitates the inclusion of an array of essential data categories, both in the SL and in the TL(s). These data categories serve as the foundational elements that underpin the terminological content, ensuring its accuracy, accessibility, and usability. The following outlines the imperative data categories to be incorporated into the CTermBank compilation (cf. Cabré 1999):

Entry Nr./Nr. of Record

Entry/Full Form of the Term

Article/Gender

Compressed Form of the Entry Term

Reference(s)/Source(s)

Grammatical Category/Part of Speech

Status/Reliability Code

ISO 639-3 Language Code

Orthographical Variation(s)

Audio Recording of Pronunciation

Definition

Reference(s)/Source(s) (for Definition)

Cross-References/Full Synonyms

Reference(s)/Source(s) for Comparative/Parallel Text(s)

Contextual Fragments/Phraseological Information

Popularised Term

Equivalents

Reference(s)/Source(s) (for Equivalents)

Special Subject Field(s)/Domain(s) and Sub-Domain(s)

Illustration(s)

Author of Record

Author’s Working Group

Date of Record

Date of Update/Modification

Among these imperative data categories some deserve explanation:

-

4.

Compressed Form of the Entry Term: Abbreviations, initialisms, acronyms, or clippings of the entry term, if available, constitute its compressed form.

-

11.

Definition: Considering the inadequacy and dispersion of terminological records in the CTerm domain, characterised by diverse interfaces and language combinations, there is a need to compile a consolidated termbank specifically designed for crisis settings. Rather than creating authentic definitions it is advisable to gather definitions from existing resources, because compiling definitions independently is resource-heavy and demands subject expertise for creation and approval, along with training to avoid pitfalls like circularity, overbroadness, narrowness, or intensional-extensional mix-ups.

The definition of the SL term should not be translated into its TL equivalent, because translating definitions carries risks, as potential disparities across languages exist, where concepts may not perfectly align across languages, especially with intensional definitions. Comparing definitions in each language can guide the determination of equivalence or close matches. Risk levels may vary across domains; even in technical fields, national standards might differ, like the composition of (eng) aluminium in DIN and BSI. A databank with a conceptual organisation needs to be advocated, preventing the treatment of homonyms/polysemes as a single entry with multiple definitions and distinguishing synonyms as separate entries but sharing the same definition, since the approach is concept oriented.

The establishment of the CTermBank aims for a unified comprehension of terms, emphasising the creation of a comprehensive English definition to serve as the base for translating into TL terms. Where available, utilising reliable English definitions with proper attribution is encouraged. Alternatively, compiling primary English definitions for translation into other languages is viable. If a definition for a particular term does not exist, crafting definitions according to plain language principles is crucial, as this aims to enhance accessibility for individuals with lower reading proficiency or those who lack subject expertise, thereby making the content more user-friendly.

-

14.

Comparative/Parallel Text(s): English comparative texts will be collected in the initial stage of gathering crisis terms, focusing on domains like civil engineering (construction), emergency medicine, and search and rescue equipment. Extracting crisis terms in English from these texts will precede their rendition into corresponding TL equivalents.

-

15.

Contextual Fragments/Phraseological Information: Not all terms necessitate contextual information; while some benefit from indicating collocations, others require context for better comprehension and illustrative usage. Deciding to include or exclude context details can be optional. The relevance of context should be determined based on the individual term's characteristics.

-

16.

Popularised Term: Popularised terms emerge from an LSP term and transition into an LGP expression. Designating a distinct data category for these terms in the CTermBank aims to improve accessibility for non-expert users like crisis victims and vulnerable citizens. This categorisation ensures their ease of understanding. Collaboration with dialectologists is crucial for identifying popularised equivalents if needed.

-

17.

Equivalents: Entry term equivalents in line with ISO 25964-1: 2011and ISO 25964-2: 2013.

-

20.

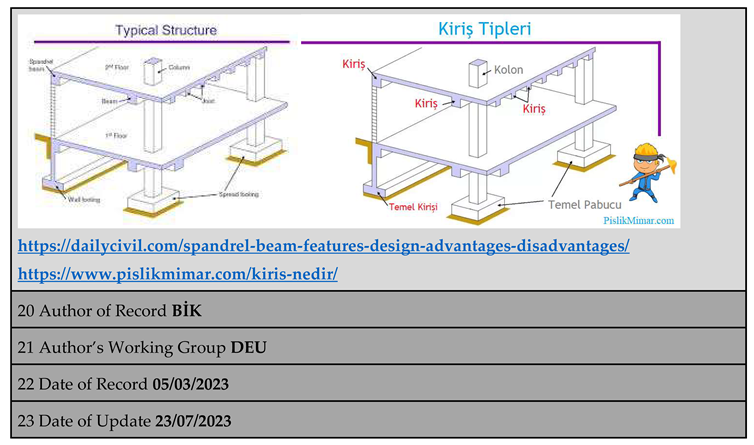

Illustration(s): Illustrations are the visual representation(s) of the entry term. This can include photographs, graphics, etc. Devoting significant project time to discern the primary illustration could be labour-intensive. We will consider prioritising the assessment of reliability among various sources—perhaps the URL could offer valuable clues. Developing a concise protocol for project officers to evaluate sources efficiently and consistently might prove beneficial. Testing this protocol iteratively could help streamline the process. Alternatively, inputting the URL directly into the relevant record field could be a feasible option. Ultimately, the decision hinges on the allocation of labour budget to this task.

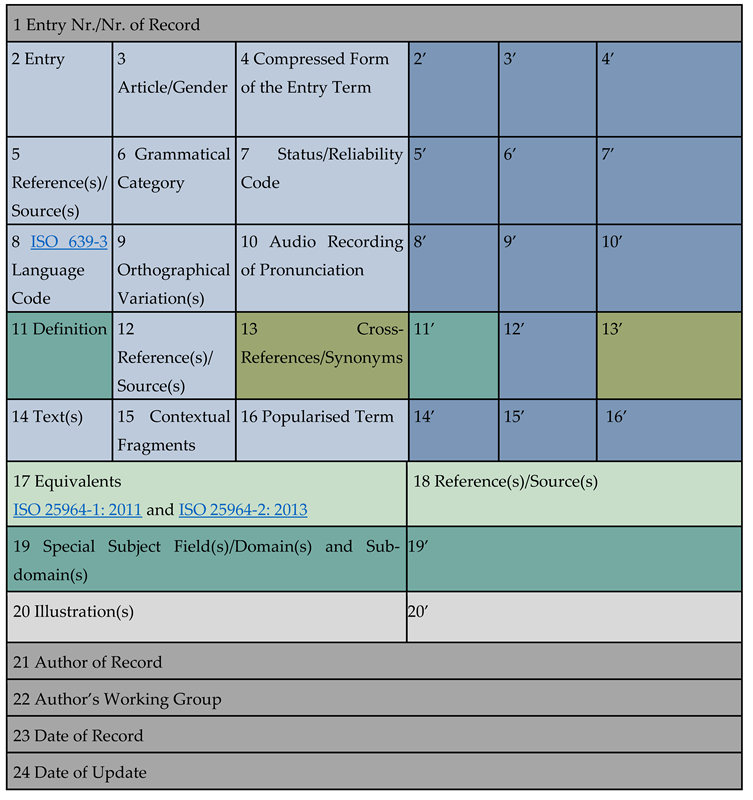

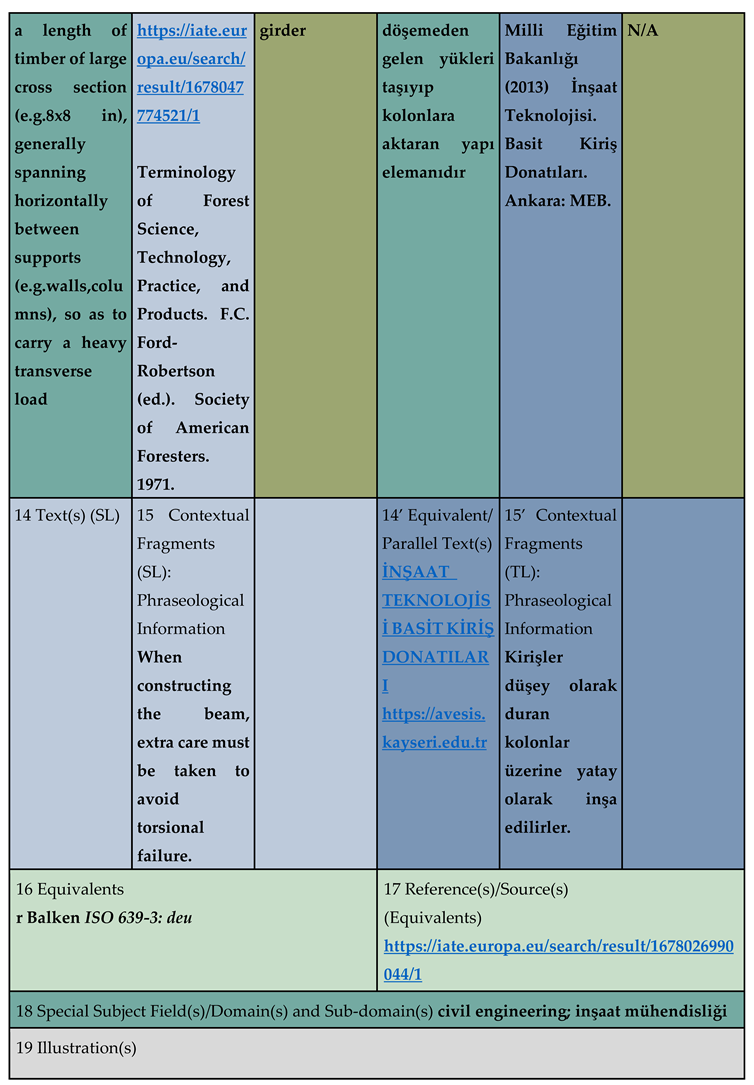

The following

Table 3 outlines the

essential data categories that should be integrated into the

CTermBank collection for comprehensive terminological coverage and accessibility. These data categories play a crucial role in facilitating accurate and multilingual communication in crisis situations (cf. Cabré 1999; Karaman 2015a; Karaman 2018; Sager 1990).

Table 3 represents a conceptual outline of a possible data record for the

CTermBank, serving as an

abstract model. Please note that, the numbers in each data category without an apostrophe indicate the

Source Language (SL), whereas numbers with an apostrophe indicate the

Target Language (TL):

Table 3.

CTermBank Data Categories.

Table 3.

CTermBank Data Categories.

7. Results

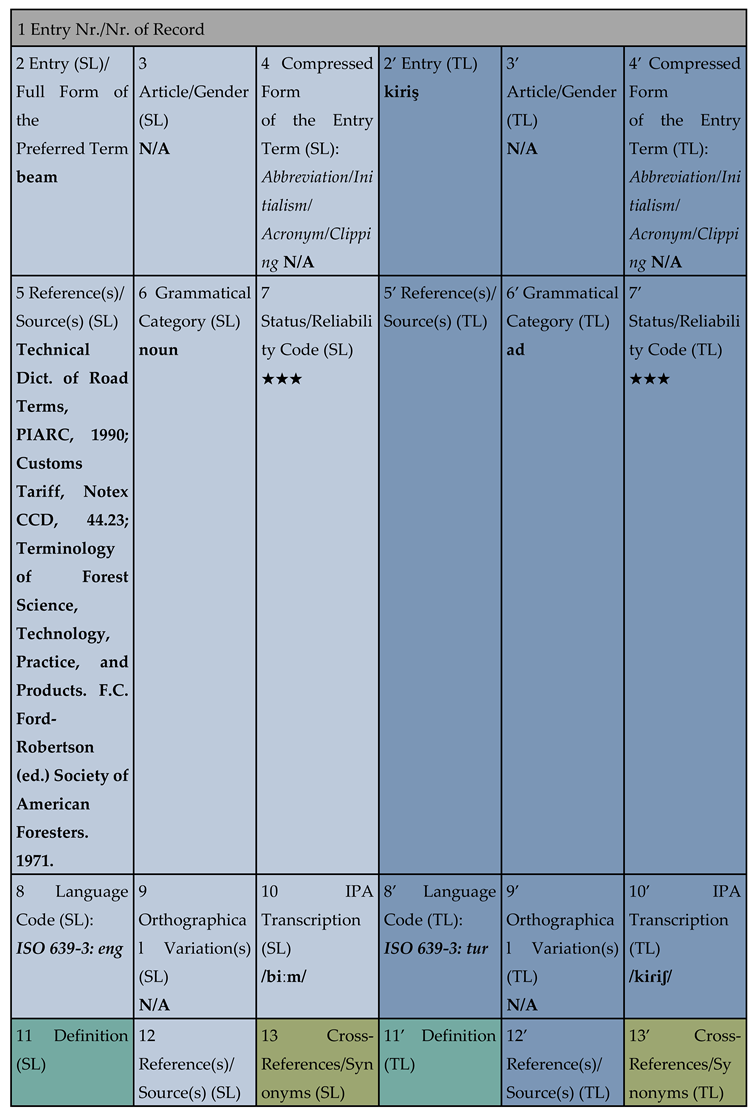

Table 4 represents a conceptual outline of a possible data record for the

CTermBank, serving as an abstract model. Please note that, the numbers in each data category without an apostrophe indicate the

Source Language (SL), whereas numbers with an apostrophe indicate the

Target Language (TL):

Table 4.

CTermBank Term Record.

Table 4.

CTermBank Term Record.

Databases efficiently retrieve information, providing users with refined search results that gradually lead to their desired term (Cabré 1999). To improve user experience, adding an auto-completion feature to the browsing interface can simplify and expedite the search process, assisting users in finding the term they need.

General search engines are useful for finding term illustrations and definitions but have limitations. Results can be extensive and lack domain-specific relevance, requiring users to invest time in sorting through them. These engines lack quality assurance for results, potentially leading to outdated or unreliable information. When using the CTermBank compilation offline, it refers users to term illustrations within the compilation, respecting copyright. Online, the CTermBank can utilise existing visual dictionaries for reliable results, enhancing information quality.

8. Discussion

As established in the previous sections, CTermPort plays a pivotal role in facilitating language support and overcoming linguistic barriers in the context of emergencies. This discussion serves to dissect the various facets of the CTermPort application, emphasising the importance of dissemination methods, end-users/target user groups, and the implications, limitations, impact, and sustainability. Furthermore, it explores the potential challenges and complexities that arise when designing and utilising CTermPort, offering insights into how these issues can be addressed to enhance crisis communication and response efforts.

8.1. Dissemination Methods

Disseminating the proposed multilingual smartphone application for CTIng requires a comprehensive strategy. Immediate delivery methods should include smartphone applications (as a new mode of delivery) and dedicated websites accessible from computer terminals. Additionally, the application should support remote printing for CTs when necessary. This multifaceted approach ensures broad accessibility, aligning with established practices (Cabré 1999; Felber 1985; Rondeau 1983; Sager 1990).

The project aims to revolutionize the working conditions of CTIs by providing them with a reliable terminological reference. CTIs face challenges in finding equivalents, especially for emerging technological terms, i.e. neologisms (Karaman 1998). They often lack extensive knowledge in various CTerm fields. Currently, their only resource is printed vocabulary lists painstakingly assembled by their own efforts. This limited resource represents their sole reference point for consulting CTermPort. Therefore, an accessible smartphone application for immediate and accurate multilingual communication is highly desirable.

8.2. End-Users/Target User Groups