Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Culture of Human SCD Patient Erythroblasts and H2O2 Exposure

2.3. Animal Treatment

2.4. Complete Blood Count and Differential

2.5. Isolation of Mouse Spleen CD71+ Erythroblasts

2.6. Cell Proliferation and Viability

2.7. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.8. RBC Sickling Analysis

2.9. Quantitative RT-PCR

2.10. Western Blot Analysis

2.11. GSH and GSSG Assay

2.12. NQO1 Activity Assay

2.13. Measurement of Intracellular Cysteine Levels

2.14. Cystine Uptake Assay

2.15. EZH2 Gene Knockdown Analysis

2.16. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

2.17. NADP+/NADPH Levels

2.18. Histology, Immunohistochemistry, and Image Analysis

2.19. Iron Content

2.20. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

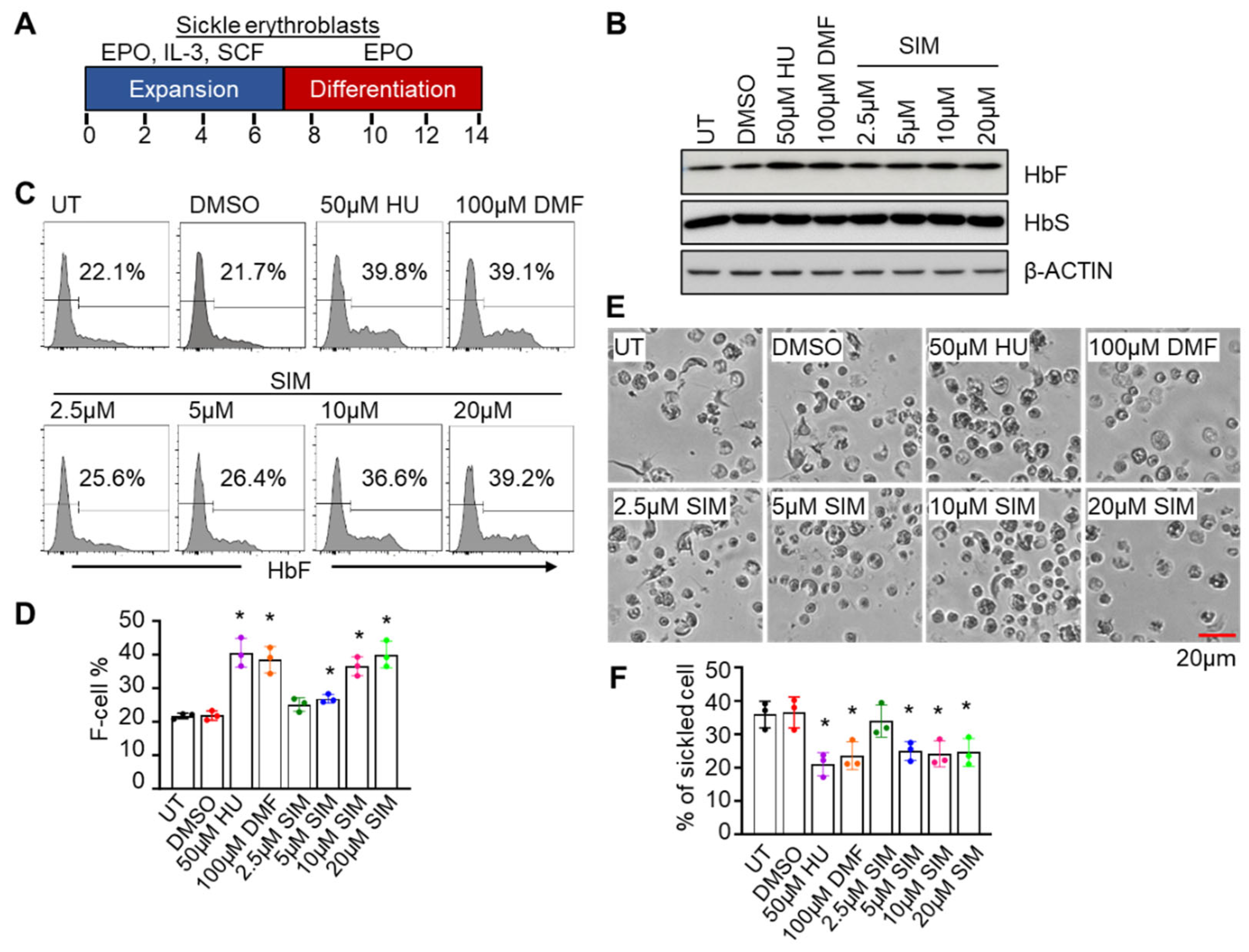

3.1. Simvastatin Activates γ-Globin Gene Expression and Reverses Sickling of SCD Erythroblasts

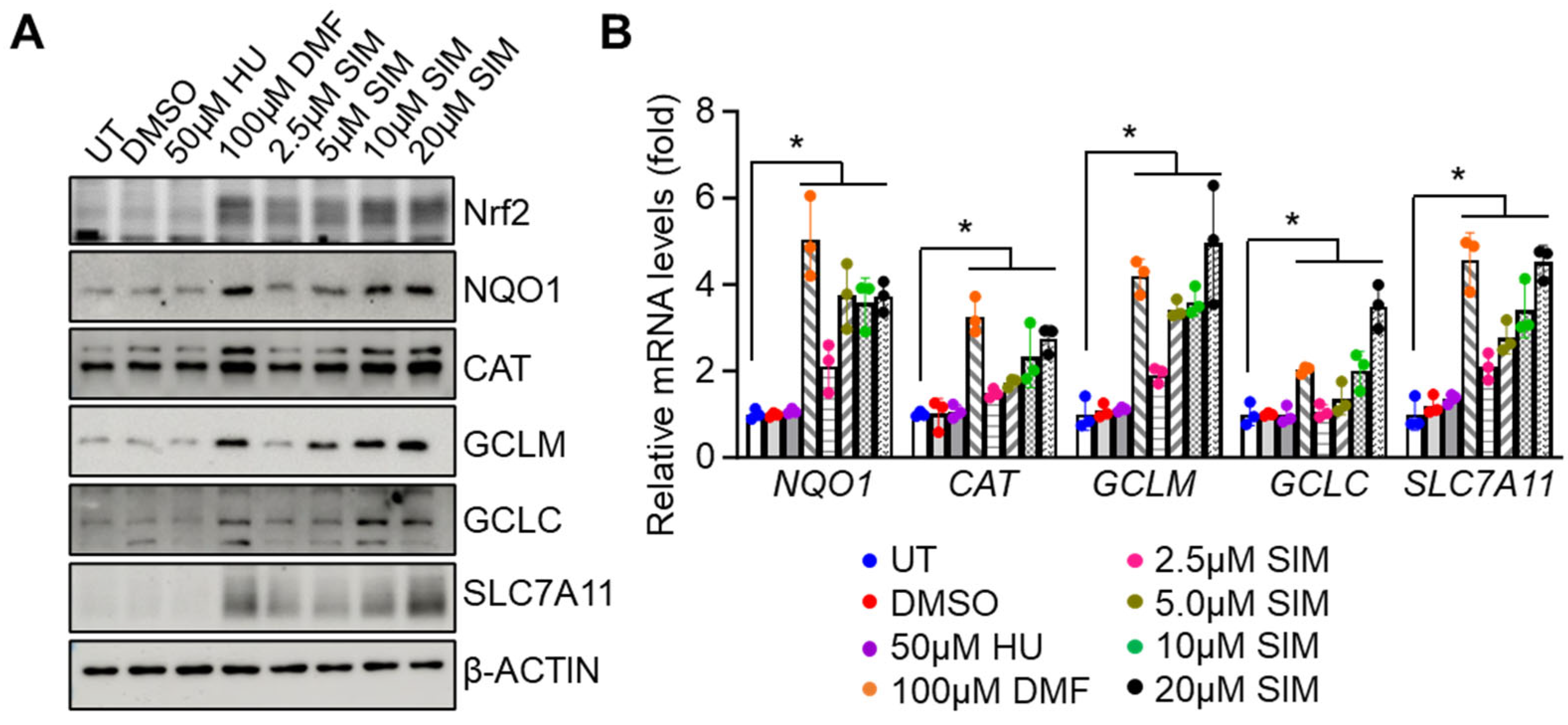

3.2. Simvastatin Increases the Expression of NRF2 and Antioxidant Proteins

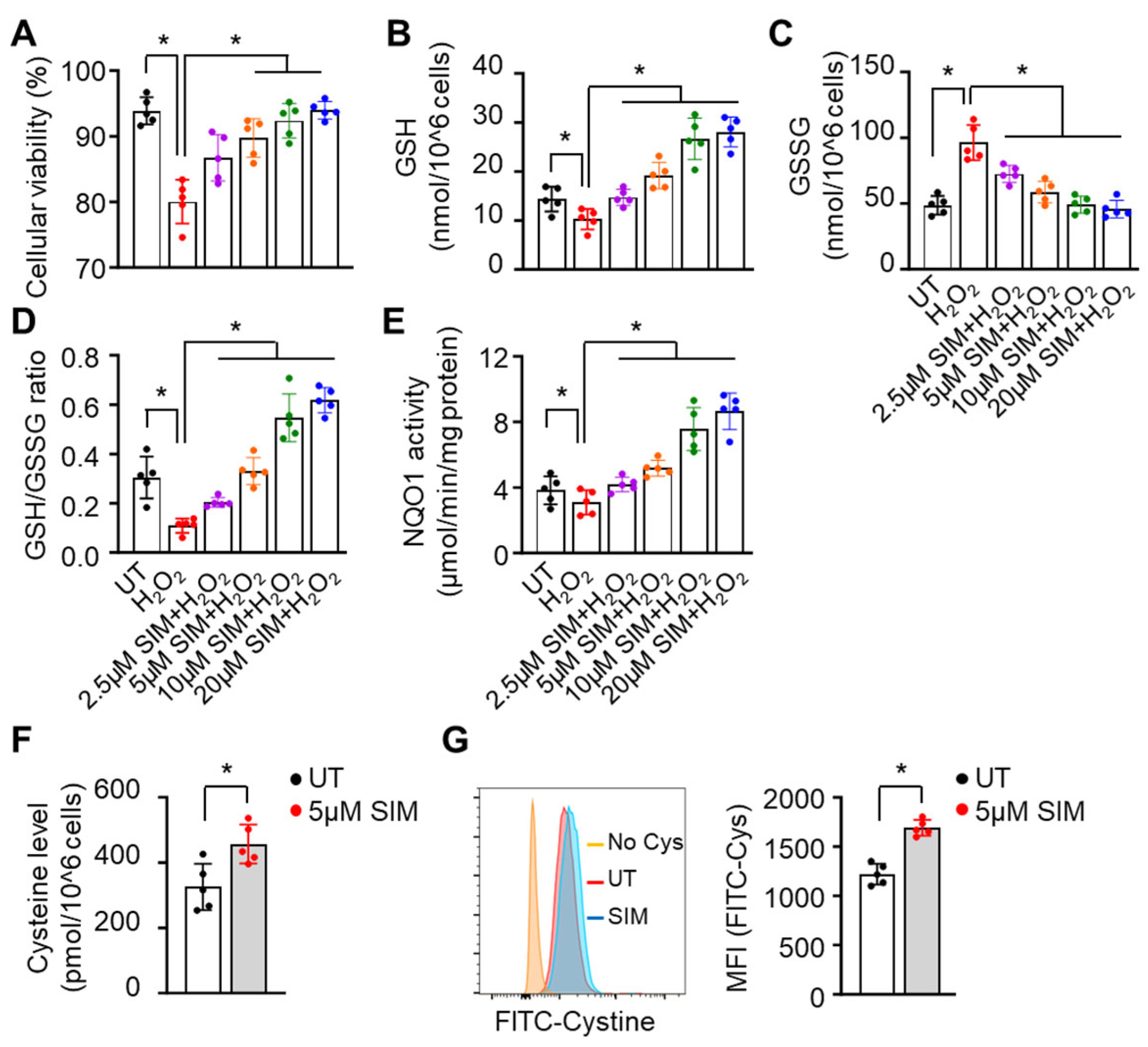

3.3. Simvastatin Enhances SCD Erythroblasts Antioxidative Capacity

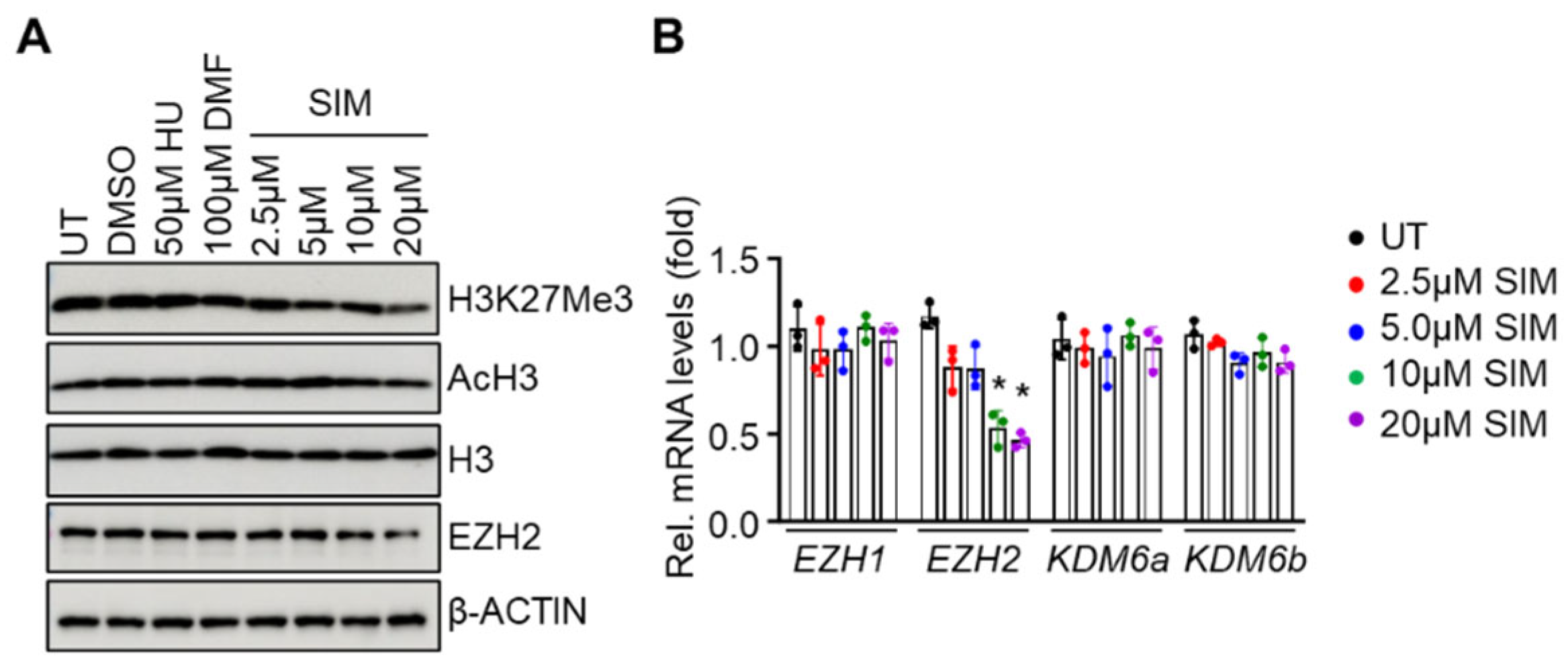

3.4. Simvastatin Attenuates EZH2 expression and Histone H3K27Me3 to Modify Chromatin Structure in Gene Regulation

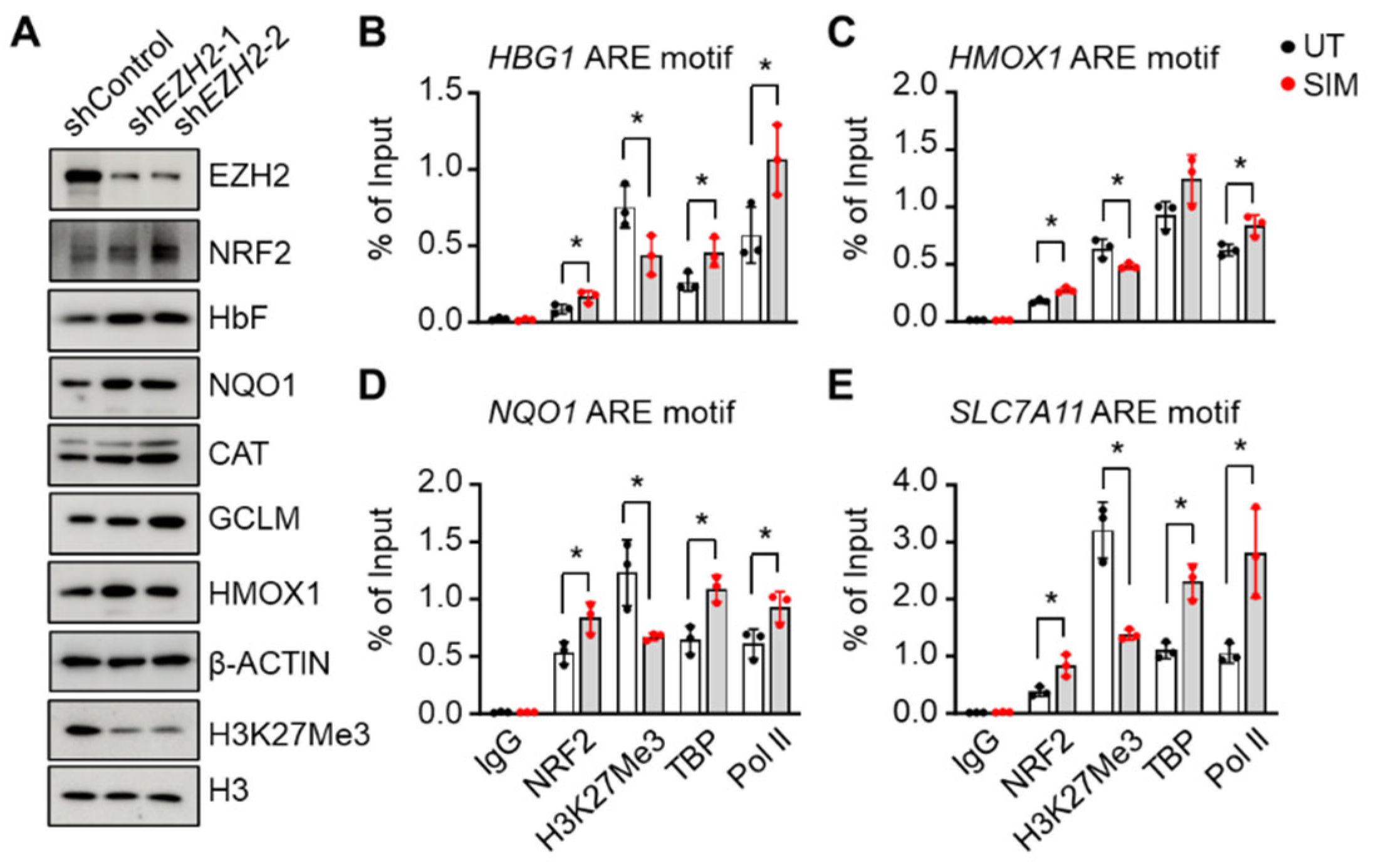

3.5. EZH2 Regulates NRF2 Expression to Modify ARE Motif Chromatin Structure on Target Genes

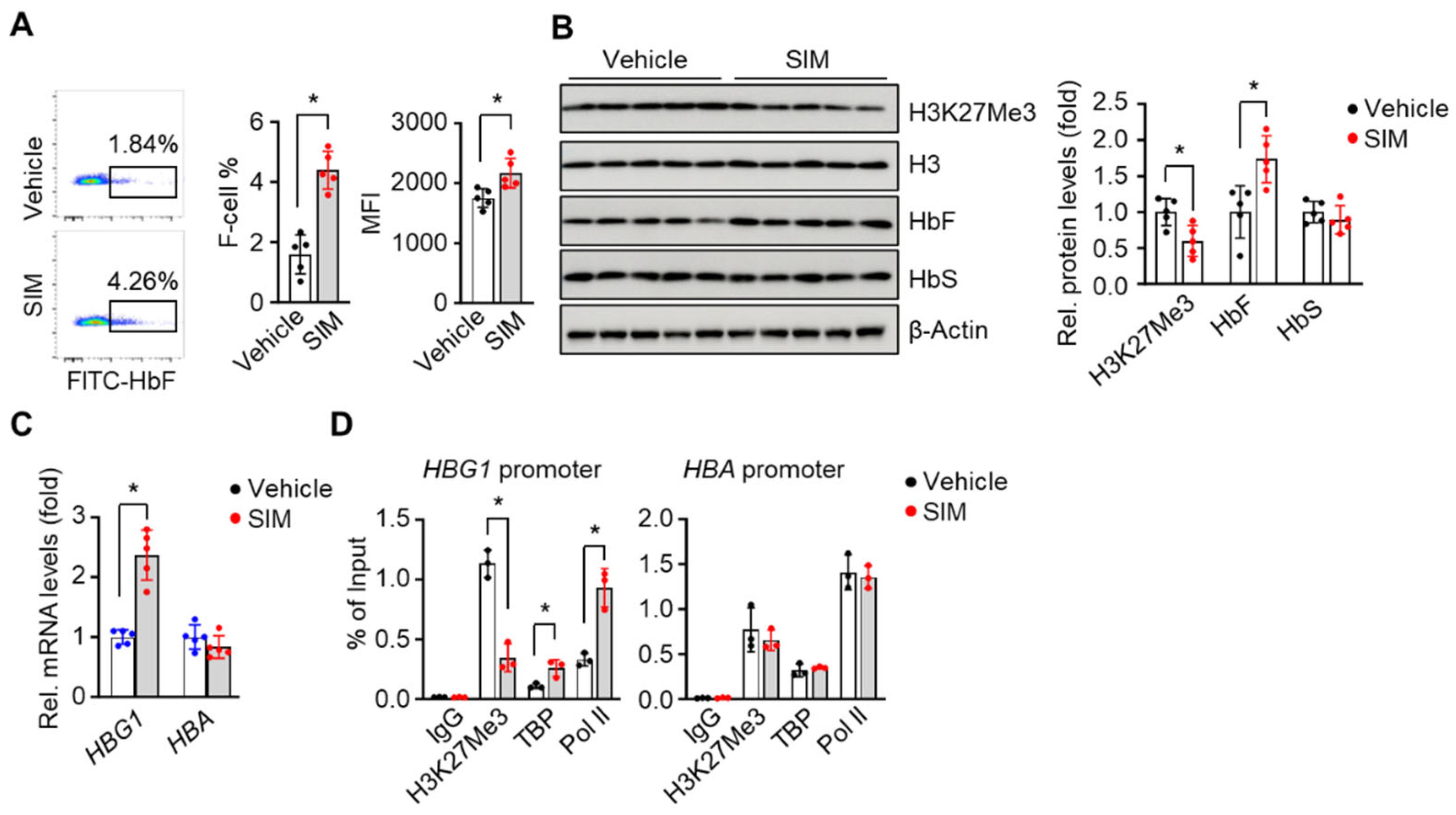

3.6. In Vivo Treatment with Simvastatin Suppresses H3K27Me3 Modification in SCD Mice

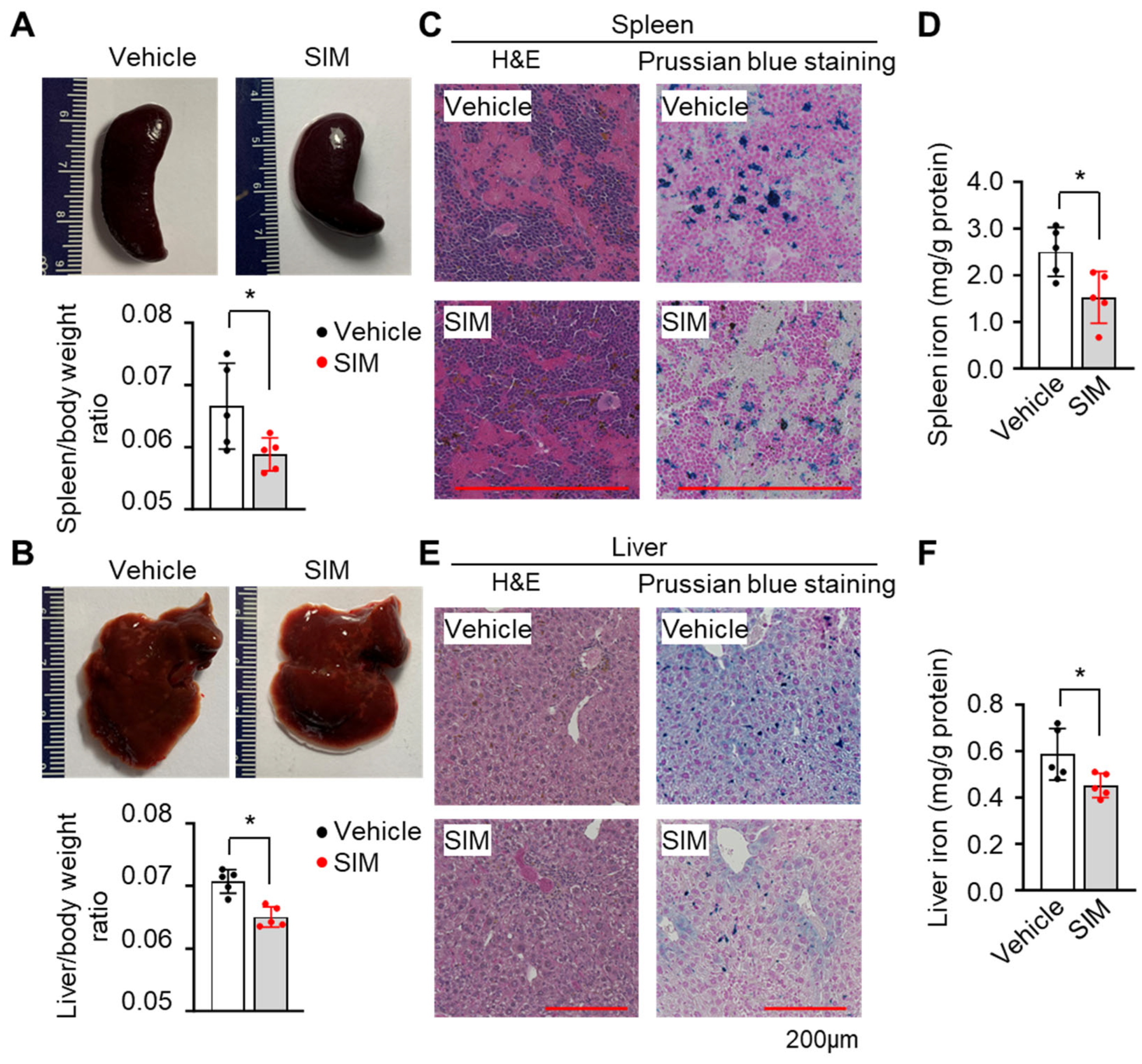

3.7. Simvastatin Protects against Organ Damage from SCD

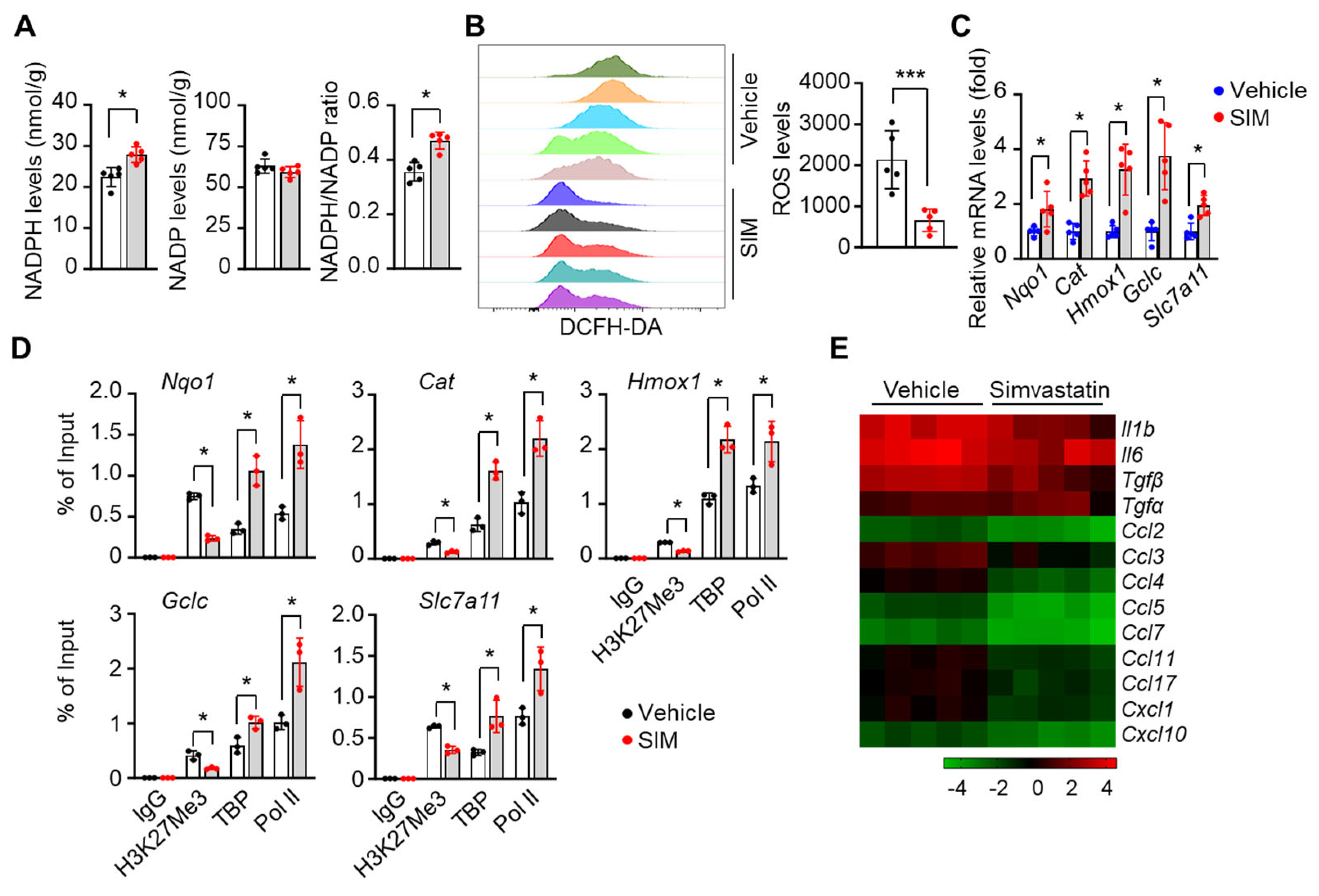

3.8. Simvastatin Reduces ROS Levels and Inflammatory Stresses in Preclinical SCD Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodgers, G.P.; Walker, E.C.; Podgor, M.J. Mortality in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 1994, 331, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.C.; Williams, T.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet 2010, 376, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.J.; Krishnamurti, L.; Kutok, J.L.; Biernacki, M.; Rogers, S.; Zhang, W.; Antin, J.H.; Ritz, J. Evidence for ineffective erythropoiesis in severe sickle cell disease. Blood 2005, 106, 3639–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, E.N.; Pialoux, V. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. IUBMB Life 2012, 64, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.G.H.; Belini Junior, E.; de Almeida, E.A.; Bonini-Domingos, C.R. Oxidative stress in sickle cell disease: An overview of erythrocyte redox metabolism and current antioxidant therapeutic strategies. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 65, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, E.; Biemond, B.J.; Otten, H.M.; Brandjes, D.P.; Schnog, J.J.; Group, C.S. Oxidative stress in sickle cell disease; pathophysiology and potential implications for disease management. Am J Hematol 2011, 86, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Mei, Y.; Yang, J.; Ji, P. Erythropoietin-regulated oxidative stress negatively affects enucleation during terminal erythropoiesis. Exp Hematol 2016, 44, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iampietro, M.; Giovannetti, T.; Tarazi, R. Hypoxia and inflammation in children with sickle cell disease: Implications for hippocampal functioning and episodic memory. Neuropsychol Rev 2014, 24, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, D.K.; Hebbel, R.P. Hypoxia/reoxygenation causes inflammatory response in transgenic sickle mice but not in normal mice. J Clin Invest 2000, 106, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bogdanov, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, K.; Zhao, S.; Song, A.; Luo, R.; Parchim, N.F.; Liu, H.; Huang, A.; et al. Hypoxia-mediated impaired erythrocyte Lands′ Cycle is pathogenic for sickle cell disease. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Xia, Y. New insights into sickle cell disease: A disease of hypoxia. Curr Opin Hematol 2013, 20, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsile, F.J.; Bediako, S.M.; Nelson, J.; Cichowitz, C.; Yu, T.; Patrick Carroll, C.; Stewart, K.; Naik, R.; Haywood, C., Jr.; Lanzkron, S. Metabolic syndrome among adults living with sickle cell disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2019, 74, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiley, D.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Umpierrez, G. Therapy insight: Metabolic and endocrine disorders in sickle cell disease. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008, 4, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darghouth, D.; Koehl, B.; Madalinski, G.; Heilier, J.F.; Bovee, P.; Xu, Y.; Olivier, M.F.; Bartolucci, P.; Benkerrou, M.; Pissard, S.; et al. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease is mirrored by the red blood cell metabolome. Blood 2011, 117, e57–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavachari, N.; Xu, X.; Harris, A.; Villagra, J.; Logun, C.; Barb, J.; Solomon, M.A.; Suffredini, A.F.; Danner, R.L.; Kato, G.; et al. Amplified expression profiling of platelet transcriptome reveals changes in arginine metabolic pathways in patients with sickle cell disease. Circulation 2007, 115, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnog, J.J.; Jager, E.H.; van der Dijs, F.P.; Duits, A.J.; Moshage, H.; Muskiet, F.D.; Muskiet, F.A. Evidence for a metabolic shift of arginine metabolism in sickle cell disease. Ann Hematol 2004, 83, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telen, M.J.; Malik, P.; Vercellotti, G.M. Therapeutic strategies for sickle cell disease: Towards a multi-agent approach. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charache, S.; Terrin, M.L.; Moore, R.D.; Dover, G.J.; Barton, F.B.; Eckert, S.V.; McMahon, R.P.; Bonds, D.R. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med 1995, 332, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niihara, Y.; Miller, S.T.; Kanter, J.; Lanzkron, S.; Smith, W.R.; Hsu, L.L.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Viswanathan, K.; Sarnaik, S.; Osunkwo, I.; et al. A Phase 3 Trial of l-Glutamine in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K.I.; Kutlar, A.; Kanter, J.; Liles, D.; Cancado, R.; Friedrisch, J.; Guthrie, T.H.; Knight-Madden, J.; Alvarez, O.A.; Gordeuk, V.R.; et al. Crizanlizumab for the Prevention of Pain Crises in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichinsky, E.; Hoppe, C.C.; Ataga, K.I.; Ware, R.E.; Nduba, V.; El-Beshlawy, A.; Hassab, H.; Achebe, M.M.; Alkindi, S.; Brown, R.C.; et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Voxelotor in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niihara, Y.; Zerez, C.R.; Akiyama, D.S.; Tanaka, K.R. Oral L-glutamine therapy for sickle cell anemia: I. Subjective clinical improvement and favorable change in red cell NAD redox potential. Am J Hematol 1998, 58, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klings, E.S.; Farber, H.W. Role of free radicals in the pathogenesis of acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. Respir Res 2001, 2, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, R.F.; Lima, E.S. Oxidative stress in sickle cell disease. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 2013, 35, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperti, S.; Nader, E.; Stier, A.; Boisson, C.; Carin, R.; Marano, M.; Robert, M.; Martin, M.; Horand, F.; Cibiel, A.; et al. Increased retention of functional mitochondria in mature sickle red blood cells is associated with increased sickling tendency, hemolysis and oxidative stress. Haematologica 2023, 108, 3086–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeeswaran, R.; Vazquez, B.A.; Thiruppathi, M.; Ganesh, B.B.; Ibanez, V.; Cui, S.; Engel, J.D.; Diamond, A.M.; Molokie, R.E.; DeSimone, J.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of LSD1 and mTOR reduces mitochondrial retention and associated ROS levels in the red blood cells of sickle cell disease. Exp Hematol 2017, 50, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boasiako, C.; Dankwah, G.B.; Aryee, R.; Hayfron-Benjamin, C.; Donkor, E.S.; Campbell, A.D. Oxidative Profile of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Med Sci (Basel) 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telen, M.J. Beyond hydroxyurea: New and old drugs in the pipeline for sickle cell disease. Blood 2016, 127, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Little, J.A.; Pecker, L.H. Advances in the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2018, 93, 1810–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.A.; McGowan, V.R.; Kato, G.J.; Partovi, K.S.; Feld, J.J.; Maric, I.; Martyr, S.; Taylor, J.G.t.; Machado, R.F.; Heller, T.; et al. Combination erythropoietin-hydroxyurea therapy in sickle cell disease: Experience from the National Institutes of Health and a literature review. Haematologica 2006, 91, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Chiba, T.; Takahashi, S.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Katoh, Y.; Oyake, T.; Hayashi, N.; Satoh, K.; Hatayama, I.; et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997, 236, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaya, K.; Suzuki, T.; Motohashi, H.; Onodera, K.; Satomi, S.; Kensler, T.W.; Yamamoto, M. Validation of the multiple sensor mechanism of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic Biol Med 2012, 53, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Qian, W.; Chen, F.; Jin, Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, X.; Lee, S.R.; Su, D.; Chen, B. ATRA protects skin fibroblasts against UV-induced oxidative damage through inhibition of E3 ligase Hrd1. Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 2294–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Zhao, F.; Gao, B.; Tan, C.; Yagishita, N.; Nakajima, T.; Wong, P.K.; Chapman, E.; Fang, D.; Zhang, D.D. Hrd1 suppresses Nrf2-mediated cellular protection during liver cirrhosis. Genes Dev 2014, 28, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada, P.; Rojo, A.I.; Chowdhry, S.; McMahon, M.; Hayes, J.D.; Cuadrado, A. SCF/beta-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol 2011, 31, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gameiro, I.; Michalska, P.; Tenti, G.; Cores, A.; Buendia, I.; Rojo, A.I.; Georgakopoulos, N.D.; Hernandez-Guijo, J.M.; Teresa Ramos, M.; Wells, G.; et al. Discovery of the first dual GSK3beta inhibitor/Nrf2 inducer. A new multitarget therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer′s disease. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 45701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorley, B.N.; Campbell, M.R.; Wang, X.; Karaca, M.; Sambandan, D.; Bangura, F.; Xue, P.; Pi, J.; Kleeberger, S.R.; Bell, D.A. Identification of novel NRF2-regulated genes by ChIP-Seq: Influence on retinoid X receptor alpha. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 7416–7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macari, E.R.; Schaeffer, E.K.; West, R.J.; Lowrey, C.H. Simvastatin and t-butylhydroquinone suppress KLF1 and BCL11A gene expression and additively increase fetal hemoglobin in primary human erythroid cells. Blood 2013, 121, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleku-Lukwete, N.; Suzuki, M.; Otsuki, A.; Tsuchida, K.; Katayama, S.; Hayashi, M.; Naganuma, E.; Moriguchi, T.; Tanabe, O.; Engel, J.D.; et al. Amelioration of inflammation and tissue damage in sickle cell model mice by Nrf2 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 12169–12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleku-Lukwete, N.; Suzuki, M.; Panda, H.; Otsuki, A.; Katsuoka, F.; Saito, R.; Saigusa, D.; Uruno, A.; Yamamoto, M. Nrf2 activation in myeloid cells and endothelial cells differentially mitigates sickle cell disease pathology in mice. Blood Adv 2019, 3, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xi, C.; Thomas, B.; Pace, B.S. Loss of NRF2 function exacerbates the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease in a transgenic mouse model. Blood 2018, 131, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Pang, J.; Zhi, W.; Chang, C.S.; Siddaramappa, U.; Shi, H.; Horuzsko, A.; Pace, B.S.; Zhu, X. Nrf2 sensitizes ferroptosis through l-2-hydroxyglutarate-mediated chromatin modifications in sickle cell disease. Blood 2023, 142, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Pace, B.; Gupta, D.; Sturtevant, S.; Li, B.; Makala, L.; Brittain, J.; Moore, N.; Vieira, B.F.; Thullen, T.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate increases fetal hemoglobin, provides heme detoxification, and corrects anemia in sickle cell disease. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, B.; Pace, B.S. NRF2 mediates gamma-globin gene regulation and fetal hemoglobin induction in human erythroid progenitors. Haematologica 2017, 102, e285–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, M.P.; Wrolstad, D.; Bakris, G.L.; Chertow, G.M.; de Zeeuw, D.; Goldsberry, A.; Linde, P.G.; McCullough, P.A.; McMurray, J.J.; Wittes, J.; et al. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. J Card Fail 2014, 20, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.P.; Reisman, S.A.; Bakris, G.L.; O′Grady, M.; Linde, P.G.; McCullough, P.A.; Packham, D.; Vaziri, N.D.; Ward, K.W.; Warnock, D.G.; et al. Mechanisms contributing to adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. Am J Nephrol 2014, 39, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macari, E.R.; Lowrey, C.H. Induction of human fetal hemoglobin via the NRF2 antioxidant response signaling pathway. Blood 2011, 117, 5987–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.; Rojo, A.I.; Velasco, D.; de Sagarra, R.M.; Cuadrado, A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibits the xenobiotic and antioxidant cell response by direct phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcription factor Nrf2. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 14841–14851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Jaiswal, A.K. GSK-3beta acts upstream of Fyn kinase in regulation of nuclear export and degradation of NF-E2 related factor 2. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 16502–16510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, N.; Montecucco, F.; Carbone, F.; Xu, S.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Sahebkar, A. Statins: Epidrugs with effects on endothelial health? Eur J Clin Invest 2020, 50, e13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shen, M.; Tan, W.L.W.; Chen, I.Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.T.; et al. Statins improve endothelial function via suppression of epigenetic-driven EndMT. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2023, 2, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lin, J.H.; Chou, C.W.; Chang, Y.F.; Yeh, S.H.; Chen, C.C. Statins increase p21 through inhibition of histone deacetylase activity and release of promoter-associated HDAC1/2. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikoo, K.; Patel, G.; Kumar, S.; Karpe, P.A.; Sanghavi, M.; Malek, V.; Srinivasan, K. Tissue specific up regulation of ACE2 in rabbit model of atherosclerosis by atorvastatin: Role of epigenetic histone modifications. Biochem Pharmacol 2015, 93, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Rosales, C.; Portilla-Fernandez, E.; Nano, J.; Wilson, R.; Lehne, B.; Mishra, P.P.; Gao, X.; Ghanbari, M.; Rueda-Ochoa, O.L.; Juvinao-Quintero, D.; et al. Epigenetic Link Between Statin Therapy and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, J.E.; Shang, Y.; Rotllan, N.; Vengrenyuk, Y.; Wu, C.; Shamir, R.; Torra, I.P.; Fernandez-Hernando, C.; Fisher, E.A.; Garabedian, M.J. Statins promote the regression of atherosclerosis via activation of the CCR7-dependent emigration pathway in macrophages. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.C.; Kim, K.K.; Shevach, E.M. Simvastatin induces Foxp3+ T regulatory cells by modulation of transforming growth factor-beta signal transduction. Immunology 2010, 130, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, N.; Maeda, T.; Abe, N. Short telomere subtelomeric hypomethylation is associated with telomere attrition in elderly diabetic patients (1). Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2019, 97, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Pi, W.; Liu, H.; Wickrema, A.; Tuan, D. NF-Y recruits both transcription activator and repressor to modulate tissue- and developmental stage-specific expression of human gamma-globin gene. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.M.; Ciavatta, D.J.; Townes, T.M. Knockout-transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease. Science 1997, 278, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wen, J.; Zhang, W.; Grenz, A.; Sun, H.; Tao, L.; Lu, G.; Alexander, D.C.; Milburn, M.V.; et al. Detrimental effects of adenosine signaling in sickle cell disease. Nat Med 2011, 17, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ling, J.; Zhang, L.; Pi, W.; Wu, M.; Tuan, D. A facilitated tracking and transcription mechanism of long-range enhancer function. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, 5532–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, S.; Hayashi, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Abe, M.; Kuroki, H.; Tokunaga, R.; Tomiyasu, S.; Tanaka, H.; Sugita, H.; Arita, T.; et al. Statins inhibit tumor progression via an enhancer of zeste homolog 2-mediated epigenetic alteration in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2014, 135, 2528–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, K.; Miyai, K.; Kato, K.; Asano, T.; Sato, A. Simvastatin-romidepsin combination kills bladder cancer cells synergistically. Transl Oncol 2021, 14, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, E.L.; Shi, Y. Histone methylation: A dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcher, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Zhang, P.; Abdulla, F.; Nguyen, P.; Killeen, T.; Xu, P.; O′Sullivan, G.; Nath, K.A.; et al. Control of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Sickle Cell Disease with the Nrf2 Activator Dimethyl Fumarate. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017, 26, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Feng, Y.; Cui, R.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C. Simvastatin protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 98, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.H.; Campbell, A.D.; Fey, S.K.; Tumanov, S.; Sumpton, D.; Blanco, G.R.; Mackay, G.; Nixon, C.; Vazquez, A.; Sansom, O.J.; et al. Targeting the Metabolic Response to Statin-Mediated Oxidative Stress Produces a Synergistic Antitumor Response. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.T.; Andersen, J.T.; Nielsen, T.K.; Cejvanovic, V.; Petersen, K.M.; Henriksen, T.; Weimann, A.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Poulsen, H.E. Simvastatin and oxidative stress in humans: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Redox Biol 2016, 9, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Joshi, T.; Vatsa, N.; Singh, B.K.; Jana, N.R. Simvastatin Restores HDAC1/2 Activity and Improves Behavioral Deficits in Angelman Syndrome Model Mouse. Front Mol Neurosci 2019, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, E.; Andrenacci, D.; Mai, A.; Valente, S.; Robijns, J.; De Vos, W.H.; Capanni, C.; Lattanzi, G. Statins and Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Affect Lamin A/C - Histone Deacetylase 2 Interaction in Human Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeck, B.; Beermann, W.; N′Guessan, P.D.; Hocke, A.C.; Opitz, B.; Eitel, J.; Dinh, Q.T.; Witzenrath, M.; Krull, M.; Suttorp, N.; et al. Simvastatin reduces Chlamydophila pneumoniae-mediated histone modifications and gene expression in cultured human endothelial cells. Circ Res 2008, 102, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodach, L.L.; Jacobs, R.J.; Voorneveld, P.W.; Wildenberg, M.E.; Verspaget, H.W.; van Wezel, T.; Morreau, H.; Hommes, D.W.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; van den Brink, G.R.; et al. Statins augment the chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer cells inducing epigenetic reprogramming and reducing colorectal cancer cell ′stemness′ via the bone morphogenetic protein pathway. Gut 2011, 60, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, N.; Neuparth, T.; Barros, S.; Santos, M.M. The anti-lipidemic drug simvastatin modifies epigenetic biomarkers in the amphipod Gammarus locusta. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 209, 111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.W.; Qi, J.W.; Hang, Y.; Wu, J.X.; Zhou, X.X.; Chen, J.Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.H. Simvastatin is beneficial to lung cancer progression by inducing METTL3-induced m6A modification on EZH2 mRNA. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 4263–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgeman, S.; Northrop, W.; Ellison, G.; Sabapathy, T.; Melton, P.E.; Newsholme, P.; Mamotte, C.D.S. Statins Do Not Directly Inhibit the Activity of Major Epigenetic Modifying Enzymes. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, E.H.; Suzuki, T.; Funayama, R.; Nagashima, T.; Hayashi, M.; Sekine, H.; Tanaka, N.; Moriguchi, T.; Motohashi, H.; Nakayama, K.; et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Bauer, D.E.; Kerenyi, M.A.; Vo, T.D.; Hou, S.; Hsu, Y.J.; Yao, H.; Trowbridge, J.J.; Mandel, G.; Orkin, S.H. Corepressor-dependent silencing of fetal hemoglobin expression by BCL11A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 6518–6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Kim, A. Characterization of histone H3K27 modifications in the beta-globin locus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 405, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Myers, G.; Schneider, E.; Wang, Y.; Mathews, R.; Lim, K.C.; Siemieniak, D.; Tang, V.; Ginsburg, D.; Balbin-Cuesta, G.; et al. Identification of novel gamma-globin inducers among all potential erythroid druggable targets. Blood Adv 2022, 6, 3280–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, C.; Kuypers, F.; Larkin, S.; Hagar, W.; Vichinsky, E.; Styles, L. A pilot study of the short-term use of simvastatin in sickle cell disease: Effects on markers of vascular dysfunction. Br J Haematol 2011, 153, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, C.; Jacob, E.; Styles, L.; Kuypers, F.; Larkin, S.; Vichinsky, E. Simvastatin reduces vaso-occlusive pain in sickle cell anaemia: A pilot efficacy trial. Br J Haematol 2017, 177, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K. Does the Interdependence between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Explain the Antioxidant Paradox? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 5698931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamialahmadi, T.; Abbasifard, M.; Reiner, Z.; Rizzo, M.; Eid, A.H.; Sahebkar, A. The Effects of Statin Treatment on Serum Ferritin Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, T.D.; Wood, J.C. How we manage iron overload in sickle cell patients. Br J Haematol 2017, 177, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Lee, S.; Won, S. Possible link between statin and iron deficiency anemia: A South Korean nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.J.; Hong, E.M.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, J.; Park, S.W.; Byun, H.W.; Koh, D.H.; Choi, M.H.; Kae, S.H.; et al. Simvastatin induces heme oxygenase-1 via NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation through ERK and PI3K/Akt pathway in colon cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46219–46229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).