Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

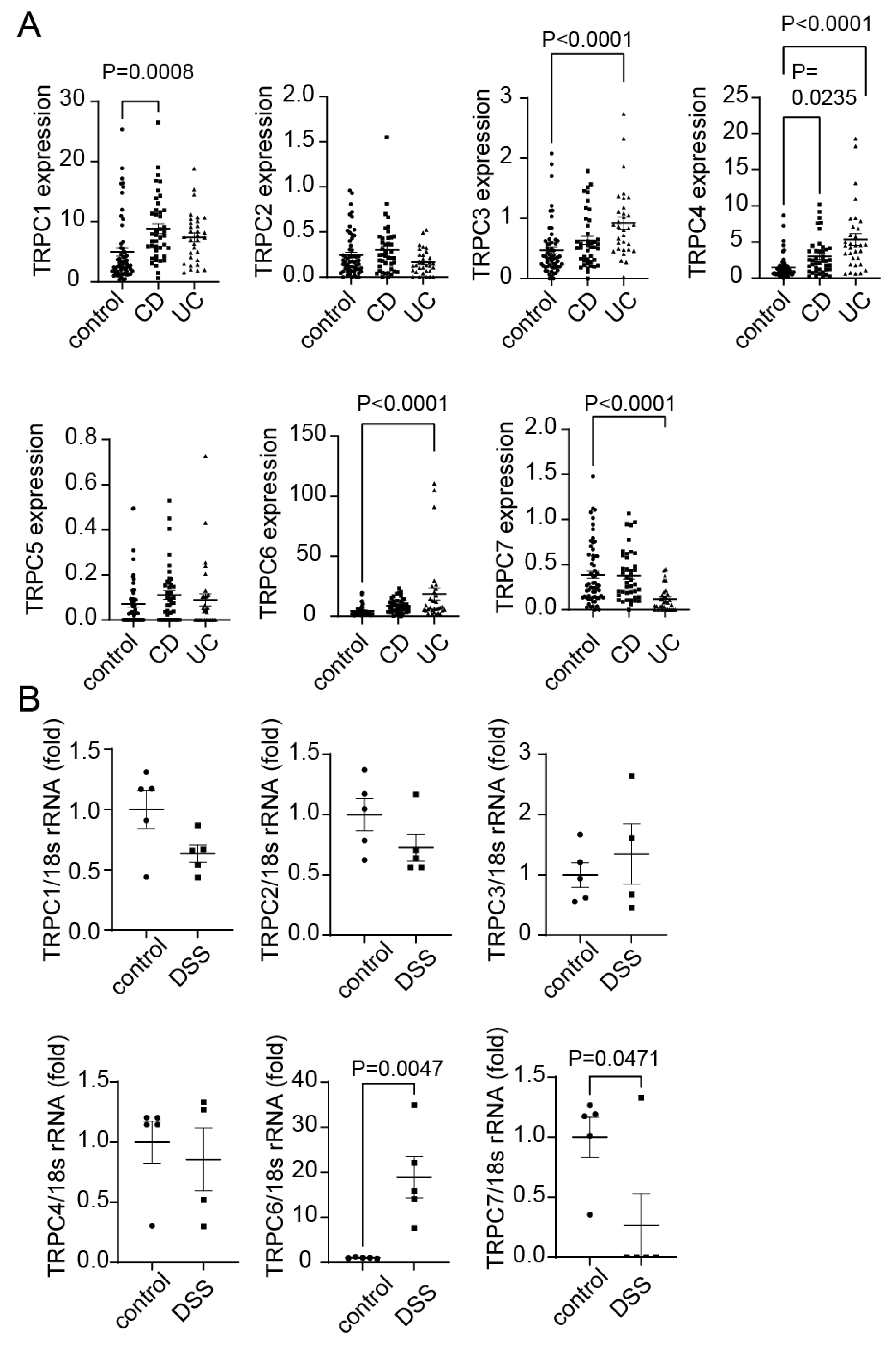

2.1. Expression of TRPC1-7 in CD and UC patients.

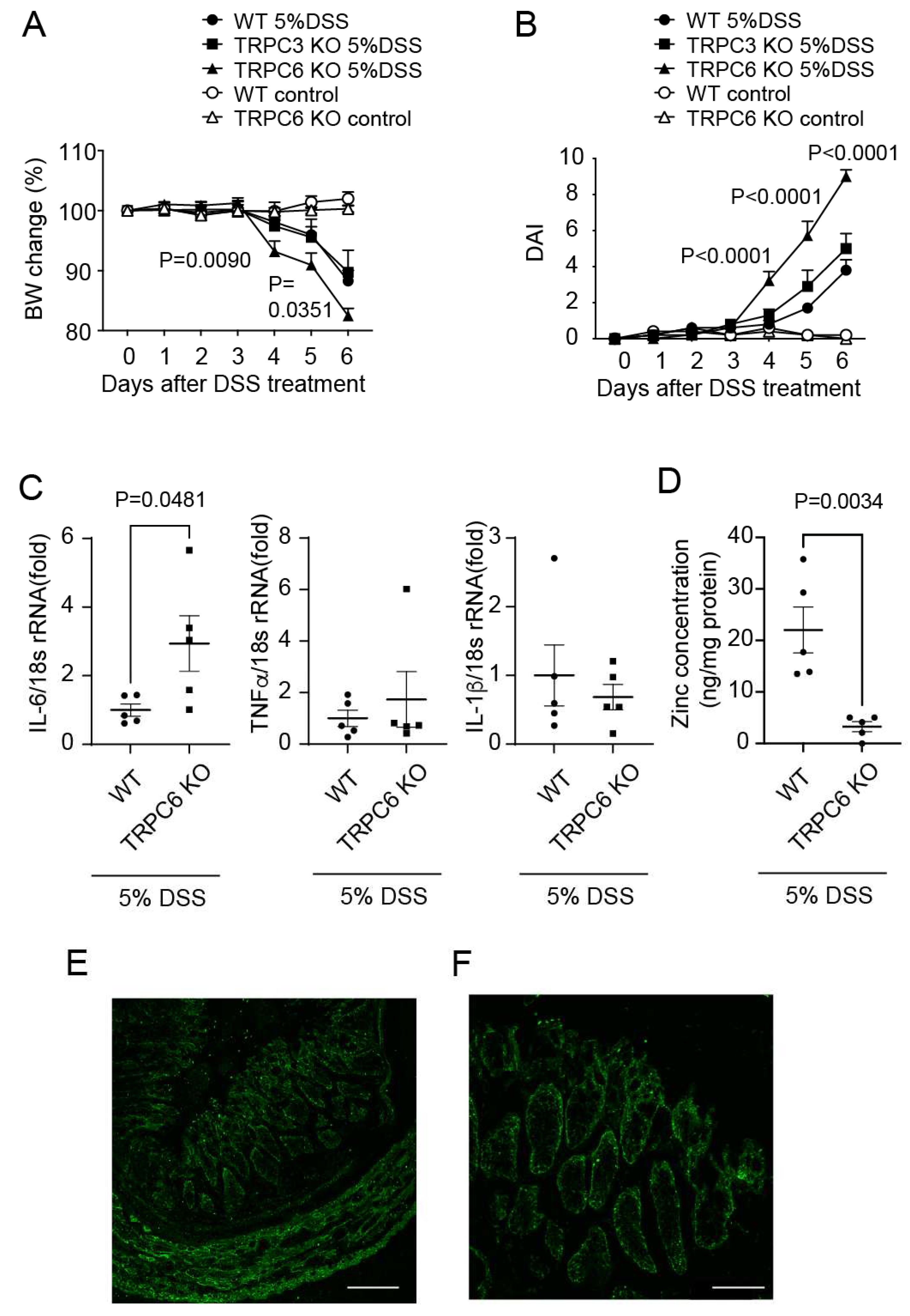

2.2. TRPC6 protects mice from DSS-induced colitis.

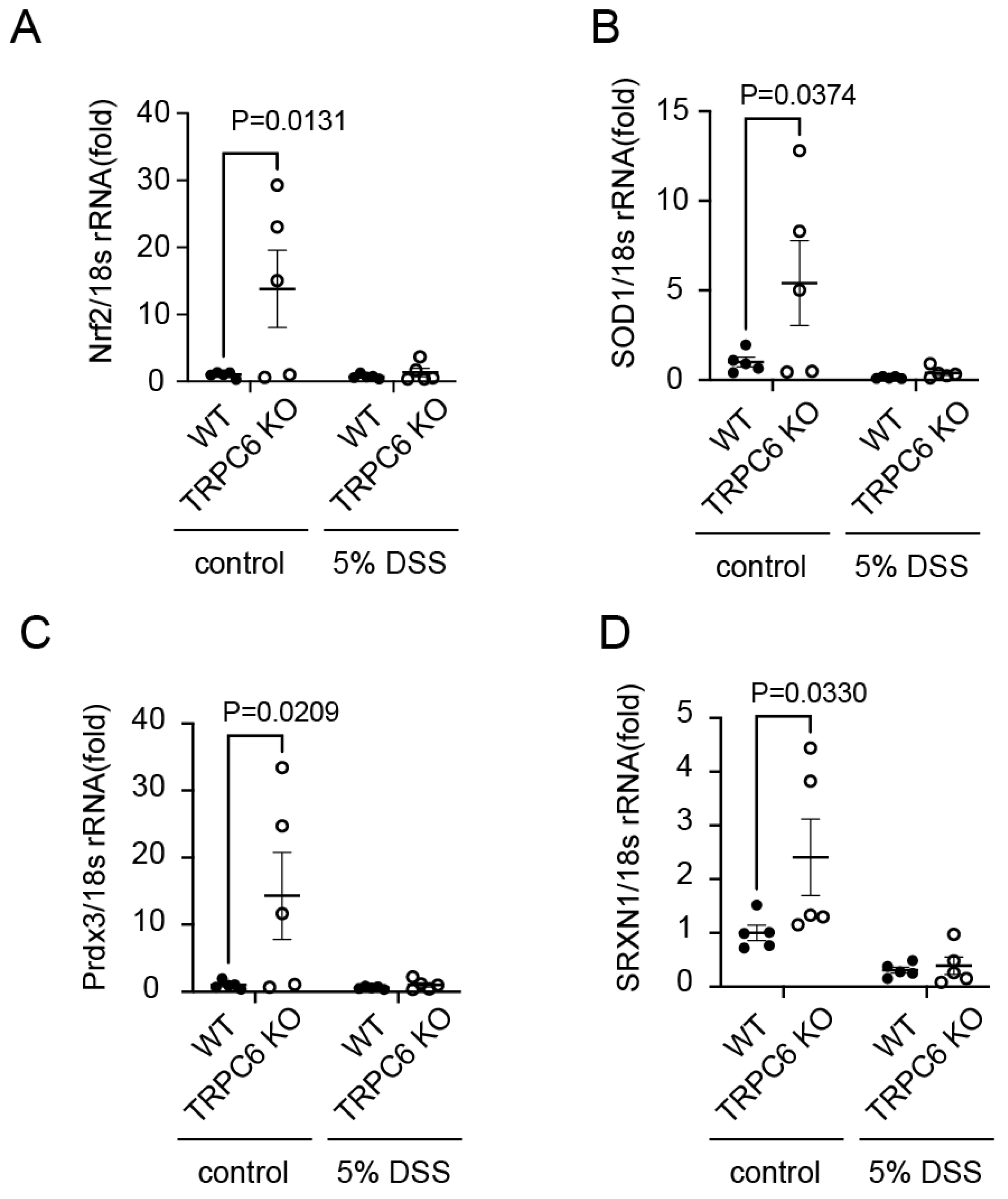

2.3. TRPC6 regulates antioxidant protein expression.

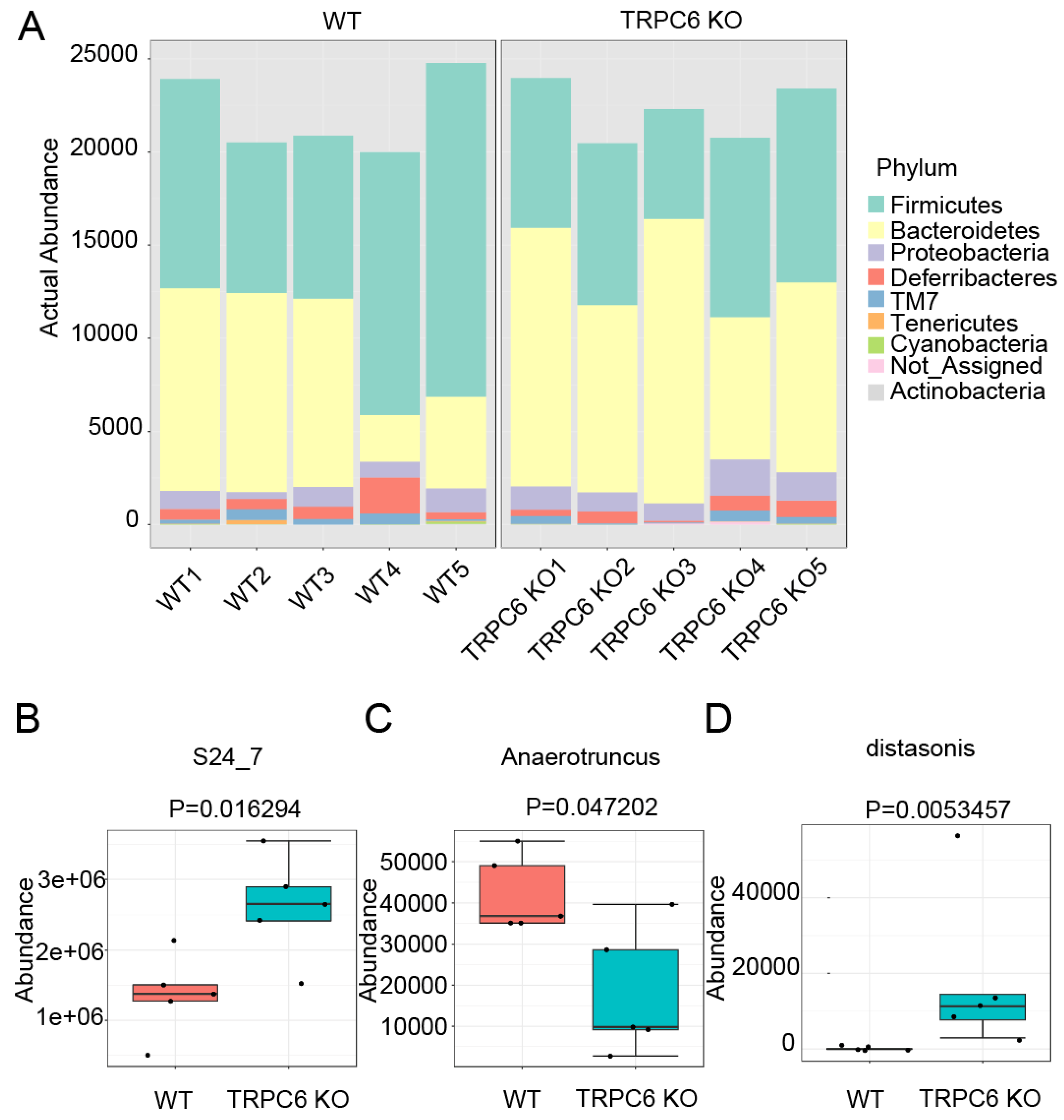

2.4. TRPC6 regulates the gut microbiota.

2.5. Activation of TRPC6 attenuates DSS-induced colitis.

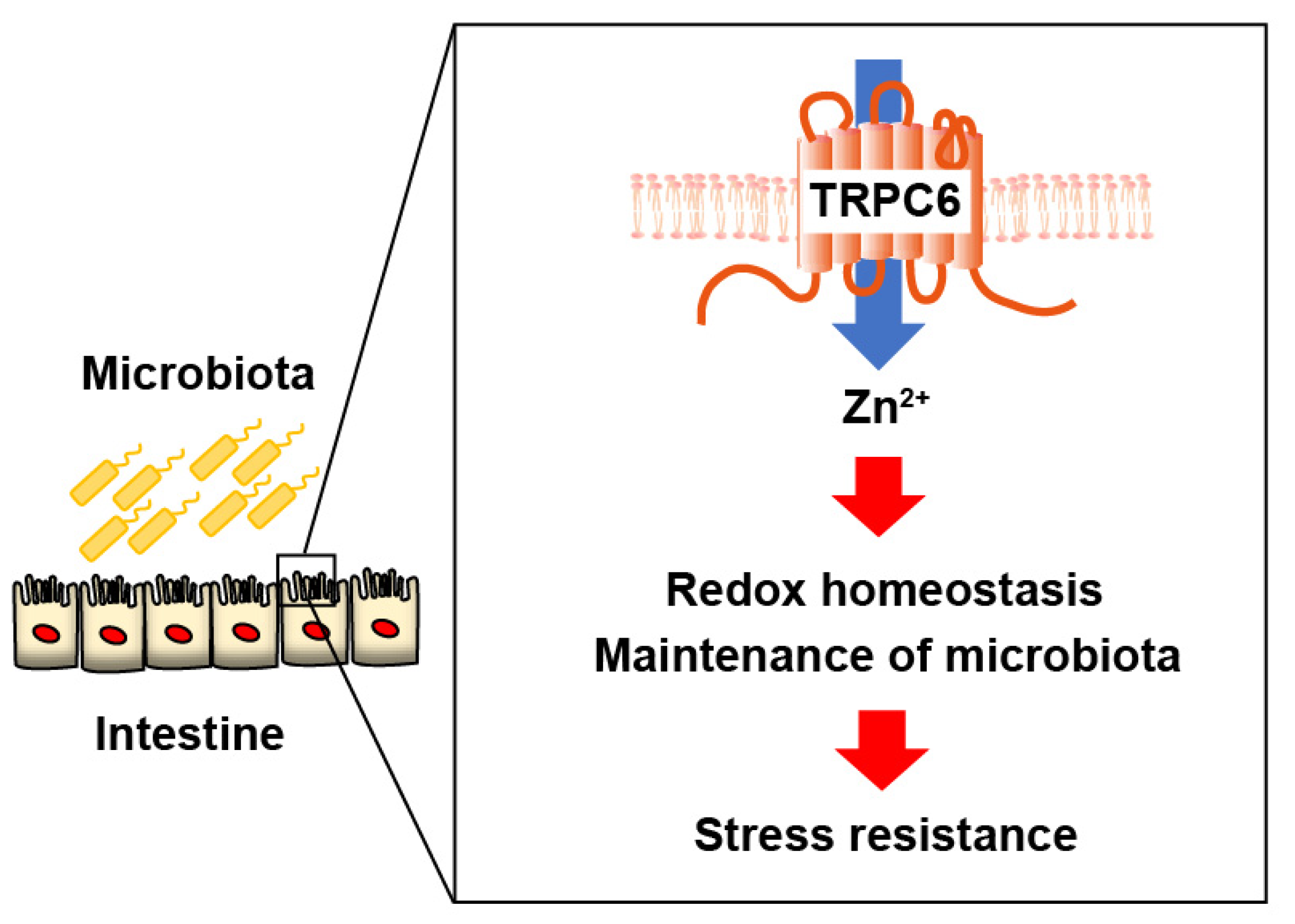

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. GEO datasets analysis

4.2. Animals

4.3. DSS-induced colitis model

4.4. Disease activity index (DAI)

4.5. PPZ2 treatment

4.6. RNA isolation and quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

4.7. Zn2+concentration

4.8. Immunohistochemistry

4.9. Gut microbiota analysis

4.10. Statistics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maloy, K.J.; Powrie, F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011, 474, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunst, C.; Schmid, S.; Michalski, M.; Tümen, D.; Buttenschön, J.; Müller, M.; Gülow, K. The Influence of Gut Microbiota on Oxidative Stress and the Immune System. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, T.T.; Monteleone, G. Immunity, Inflammation, and Allergy in the Gut. Science 2005, 307, 1920–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakase, H.; Uchino, M.; Shinzaki, S.; Matsuura, M.; Matsuoka, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Saruta, M.; Hirai, F.; Hata, K.; Hiraoka, S.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 489–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, A.K.; Sałaga, M.; Siwiński, P.; Włodarczyk, M.; Dziki, A.; Fichna, J. Oxidative Stress Does Not Influence Subjective Pain Sensation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Hamouda, H. p53 antibodies, metallothioneins, and oxidative stress markers in chronic ulcerative colitis with dysplasia. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 2417–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Chen, J.-S.; Wu, W.-M.; Liao, T.-N.; Chu, P.; Lin, S.-H.; Chuang, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-F. Myeloperoxidase serves as a marker of oxidative stress during single haemodialysis session using two different biocompatible dialysis membranes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2005, 20, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.W.; Yong, S.L.; Eiznhamer, D.; Keshavarzian, A. Glutathione content of colonic mucosa: evidence for oxidative damage in active ulcerative colitis. . Dig. Dis. Sci. 1998, 43, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, G.; Trivedi, P.P.; Sandala, B. Oxidative stress in ulcerative colitis: an old concept but a new concern. Free. Radic. Res. 2012, 46, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, I.; Raijmakers, M.; Peters, W.; Hoensch, H.; Kirch, W. Homocysteine, Cysteine, and Glutathione in Human Colonic Mucosa: Elevated Levels of Homocysteine in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003, 48, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, D.J. The oxidative stress of zinc deficiency. Metallomics 2011, 3, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, O.; Tako, E. Chronic Dietary Zinc Deficiency Alters Gut Microbiota Composition and Function. IECN 2020. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 16.

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, B. The Impact of Zinc and Zinc Homeostasis on the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier and Intestinal Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, S.; Rubin, D.T.; Gulotta, G.; Wroblewski, K.; Pekow, J. Zinc Deficiency is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarali, H.I.; Hawkins, E.G.; Ross, G.R.; Kang, M. Ion channel remodeling in gastrointestinal inflammation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghishan, F.K.; Kiela, P.R. Epithelial Transport in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, M.; Tanaka, T.; Mangmool, S.; Nishiyama, K.; Nishimura, A. Canonical Transient Receptor Potential Channels and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Plasticity. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2020, 9, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibon, J.; Tu, P.; Bohic, S.; Richaud, P.; Arnaud, J.; Zhu, M.; Boulay, G.; Bouron, A. The over-expression of TRPC6 channels in HEK-293 cells favours the intracellular accumulation of zinc. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 2011, 1808, 2807–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onohara, N.; Nishida, M.; Inoue, R.; Kobayashi, H.; Sumimoto, H.; Sato, Y.; Mori, Y.; Nagao, T.; Kurose, H. TRPC3 and TRPC6 are essential for angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 5305–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, S.; Nishiyama, K.; Furumoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Tang, X.; Kato, Y.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Kaneko, T.; Mangmool, S.; et al. Myocardial TRPC6-mediated Zn2+ influx induces beneficial positive inotropy through β-adrenoceptors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, N.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Watanabe, M.; Kuroda, T.; Nishimura, A.; Miyano, K.; Yasuda, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Sato, Y.; Ide, T.; et al. TRPC3 positively regulates reactive oxygen species driving maladaptive cardiac remodeling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numaga-Tomita, T.; Shimauchi, T.; Kato, Y.; Nishiyama, K.; Nishimura, A.; Sakata, K.; Inada, H.; Kita, S.; Iwamoto, T.; Nabekura, J.; et al. Inhibition of transient receptor potential cation channel 6 promotes capillary arterialization during post-ischaemic blood flow recovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 180, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, T.; de Souza, P.; Speca, S.; Somensi, L.B.; Mariano, L.N.B.; Cury, B.J.; dos Anjos, M.F.; Quintão, N.L.M.; Dubuqoy, L.; Desreumax, P.; et al. Luteolin prevents irinotecan-induced intestinal mucositis in mice through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 2393–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstgrasser, A.; Melhem, H.; Leonardi, I.; Atrott, K.; Schäfer, M.; Werner, S.; Rogler, G.; Frey-Wagner, I. Cell-specific Activation of the Nrf2 Antioxidant Pathway Increases Mucosal Inflammation in Acute but Not in Chronic Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 11, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, J.; Ni, J.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Karim, N.; Chen, W. Mulberry Anthocyanins Ameliorate DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis by Improving Intestinal Barrier Function and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Yi, Z.; Tuo, B.; Li, T.; Liu, X. Pathophysiological role of ion channels and transporters in gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 8109–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wan, H.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Lu, C.; Yang, S.; Tuo, B.; Dong, H. Molecular mechanisms of caffeine-mediated intestinal epithelial ion transports. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 1700–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Ghishan, F.K. Impaired mucin synthesis and bicarbonate secretion in the colon of NHE8 knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G335–G343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheis, P.J.; Clarke, L.L.; Meneton, P.; Harline, M.; Boivin, G.P.; Stemmermann, G.; Duffy, J.J.; Doetschman, T.; Miller, M.L.; E Shull, G. Targeted disruption of the murine Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 2 gene causes reduced viability of gastric parietal cells and loss of net acid secretion. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Priyamvada, S.; Ge, Y.; Jayawardena, D.; Singhal, M.; Anbazhagan, A.N.; Chatterjee, I.; Dayal, A.; Patel, M.; Zadeh, K.; et al. A Novel Role of SLC26A3 in the Maintenance of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Integrity. Gastroenterology 2020, 160, 1240–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, K.; Nagao, T.; Kawakubo, K.; Ibayashi, S.; Aoyagi, K.; Yano, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Kanamoto, K.; Iida, M.; Sadoshima, S.; et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide affords gastric mucosal protection by activating potassium channel in Wistar rat. Gastroenterology 1998, 114, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, Q.; Ye, Y.; Tao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Miao, Y.; Jia, J.; Miao, J. Alterations in metabolome and microbiome signatures provide clues to the role of antimicrobial peptide KT2 in ulcerative colitis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1027658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. Available online: http://www.proteinatlas.org/ (accessed on day month year). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertin, S.; Raz, E. Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels in T cells. Semin. Immunopathol. 2015, 38, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsvilovskyy, V.V.; Zholos, A.V.; Aberle, T.; Philipp, S.E.; Dietrich, A.; Zhu, M.X.; Birnbaumer, L.; Freichel, M.; Flockerzi, V. Deletion of TRPC4 and TRPC6 in Mice Impairs Smooth Muscle Contraction and Intestinal Motility In Vivo. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paone, P.; Cani, P. D. , Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut. 2020, 69, (12), 2232–2243, http://101136/gutjnl. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantis, N.J.; Rol, N.; Corthésy, B. Secretory IgA's complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Deep, G.; Yadav, H. Role of TRP Channels in Shaping the Gut Microbiome. Pathogens 2020, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronan, E.A.; Xiao, R.; Xu, X.S. TRP channels: Intestinal bloating TRiPs up pathogen avoidance. Cell Calcium 2021, 98, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Nwe, P.-K.; Yang, Y.; Rosen, C.E.; Bielecka, A.A.; Kuchroo, M.; Cline, G.W.; Kruse, A.C.; Ring, A.M.; Crawford, J.M.; et al. A Forward Chemical Genetic Screen Reveals Gut Microbiota Metabolites That Modulate Host Physiology. Cell 2019, 177, 1217–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.I.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.M. Bacteroides fragilis Enterotoxin Induces Sulfiredoxin-1 Expression in Intestinal Epithelial Cell Lines Through a Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases- and Nrf2-Dependent Pathway, Leading to the Suppression of Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numaga-Tomita, T.; Oda, S.; Nishiyama, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nishimura, A.; Nishida, M. TRPC channels in exercise-mimetic therapy. Pfl?gers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2018, 471, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, S.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Kitajima, N.; Toyama, T.; Harada, E.; Shimauchi, T.; Nishimura, A.; Ishikawa, T.; Kumagai, Y.; Birnbaumer, L.; et al. TRPC6 counteracts TRPC3-Nox2 protein complex leading to attenuation of hyperglycemia-induced heart failure in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansuwan, K.; Jintasataporn, O.; Rink, L.; Triwutanon, S.; Wessels, I. Effects of Zinc Status on Expression of Zinc Transporters, Redox-Related Enzymes and Insulin-like Growth Factor in Asian Sea Bass Cells. Biology 2023, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.B.; Thorn, T.L.; Lee, M.-T.; Kim, Y.; Comrie, J.M.C.; Bai, Z.S.; Johnson, E.L.; Aydemir, T.B. Metal transporter SLC39A14/ZIP14 modulates regulation between the gut microbiome and host metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2023, 325, G593–G607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwendi, E.; Iwaya, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Hara, H.; Ishizuka, S. Zinc deficiency induces dysregulation of cytokine productions in an experimental colitis of rats. Biomed. Res. 2012, 33, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foligné, B.; George, F.; Standaert, A.; Garat, A.; Poiret, S.; Peucelle, V.; Ferreira, S.; Sobry, H.; Muharram, G.; Lucau-Danila, A.; et al. High-dose dietary supplementation with zinc prevents gut inflammation: Investigation of the role of metallothioneins and beyond by transcriptomic and metagenomic studies. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 12615–12633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, A.K.; Grabrucker, A.M. Zinc Deficiency During Pregnancy Leads to Altered Microbiome and Elevated Inflammatory Markers in Mice. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, Y.; Cai, R.; Volchuk, A.; Steinberg, B.E.; Saito, Y.; Matsuzawa, A.; Grinstein, S.; Freeman, S.A. Lipid peroxidation increases membrane tension, Piezo1 gating, and cation permeability to execute ferroptosis. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 1282–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.-B.; Li, T.-T.; Huo, D.; Qu, S.; Li, X.V.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Lima, S.F.; Shi, H.-Q.; Wang, A.; Putzel, G.G.; et al. Genetic manipulation of gut microbes enables single-gene interrogation in a complex microbiome. Cell 2022, 185, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.E.; Diamond, S.; Cress, B.F.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Lou, Y.C.; Borges, A.L.; Shivram, H.; He, C.; Xu, M.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Species- and site-specific genome editing in complex bacterial communities. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 7, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ishikawa, D.; Ohkusa, T.; Fukuda, S.; Nagahara, A. Hot topics on fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1068567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mahi, N.; Najafabadi, M.F.; Pilarczyk, M.; Kouril, M.; Medvedovic, M. GREIN: An Interactive Web Platform for Re-analyzing GEO RNA-seq Data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.A.; Perrigoue, J.; Mortha, A.; Iuga, A.; Song, W.-M.; Neiman, E.M.; Llewellyn, S.R.; Di Narzo, A.; Kidd, B.A.; Telesco, S.E.; et al. A functional genomics predictive network model identifies regulators of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Sert, N.P.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Sert, N.P.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2. 0. PLOS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perše, M.; Cerar, A. Dextran Sodium Sulphate Colitis Mouse Model: Traps and Tricks. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, E.; Walker, J.; Thiesen, A.; Churchill, T.; Madsen, K. cis-Urocanic Acid Attenuates Acute Dextran Sodium Sulphate-Induced Intestinal Inflammation. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e13676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, K.; Nishimura, A.; Shimoda, K.; Tanaka, T.; Kato, Y.; Shibata, T.; Tanaka, H.; Kurose, H.; Azuma, Y.-T.; Ihara, H.; et al. Redox-dependent internalization of the purinergic P2Y 6 receptor limits colitis progression. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabj0644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, T.; Ishaq, M.; Karpiniec, S.; Park, A.; Stringer, D.; Singh, N.; Ratanpaul, V.; Wolfswinkel, K.; Fitton, H.; Caruso, V.; et al. Oral Macrocystis pyrifera Fucoidan Administration Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties and Improves DSS-Induced Colitis in C57BL/6J Mice. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, K.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Toyama, C.; Nishimura, A.; Yamashita, T.; Matsunaga, N.; Koyanagi, S.; Azuma, Y.; et al. Ibudilast attenuates doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity by suppressing formation of TRPC3 channel and NADPH oxidase 2 protein complexes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 3723–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, K.; Aono, K.; Fujimoto, Y.; Kuwamura, M.; Okada, T.; Tokumoto, H.; Izawa, T.; Okano, R.; Nakajima, H.; Takeuchi, T.; et al. Chronic kidney disease after 5/6 nephrectomy disturbs the intestinal microbiota and alters intestinal motility. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 6667–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.; Xia, J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).