Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

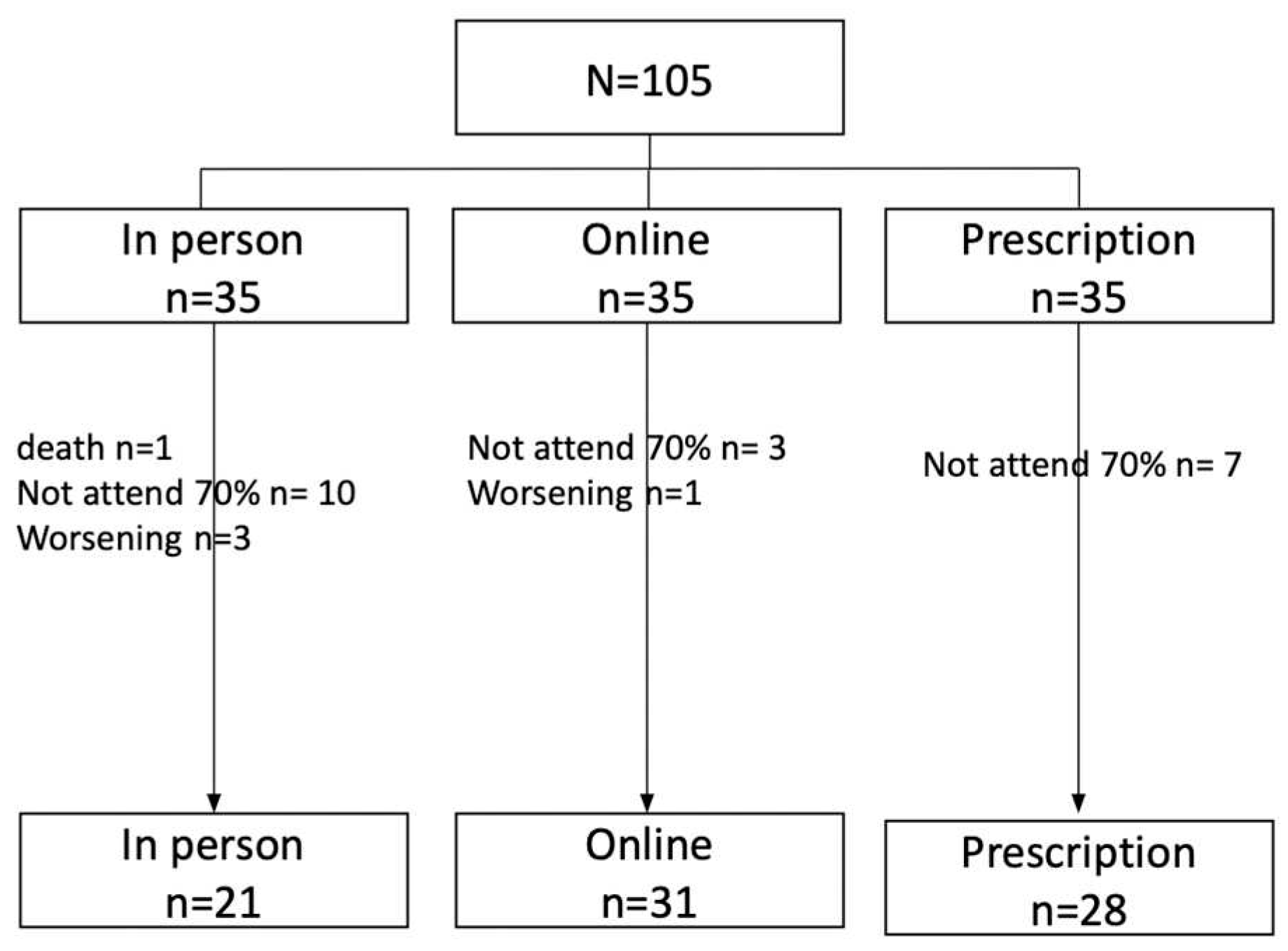

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic description of the sample

3.2. Description of the clinical status of the sample

3.3. Quality of Life Results

3.4. Reliability of the QLQ-C30

3.5. Regression analysis results.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heiman J, Onerup A, Wessman C, Olofsson Bagge R. Recovery after breast cancer surgery following recommended pre and postoperative physical activity: (PhysSURG-B) randomized clinical trial. British Journal of Surgery [Internet]. 2021 Jan 27 [cited 2024 Jan 29];108(1):32–9. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi S, Tevaarwerk AJ, Sesto M, Van Remortel B, Date P, Gangnon R, et al. Effect of a technology-supported physical activity intervention on health-related quality of life, sleep, and processes of behavior change in cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology [Internet]. 2020 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Nov 22];29(11):1917–26. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32808383/.

- Parkinson J, Bandera A, Crichton M, Shannon C, Woodward N, Hodgkinson A, et al. Poor Muscle Status, Dietary Protein Intake, Exercise Levels, Quality of Life and Physical Function in Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer at Chemotherapy Commencement and during Follow-Up. Curr Oncol [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Nov 22];30(1):688–703. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36661703/.

- Odikpo LC, Chiejina EN. Assessment of Practice and Outcome of Exercise on Quality of Life of Women with Breast Cancer in Delta State. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Nov 22];22(8):2377–83. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34452549/.

- Aydin M, Kose E, Odabas I, Bingul BM, Demirci D, Aydin Z. The Effect of Exercise on Life Quality and Depression Levels of Breast Cancer Patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Nov 22];22(3):725–32. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33773535/.

- García-Soidán JL, Pérez-Ribao I, Leirós-Rodríguez R, Soto-Rodríguez A. Long-Term Influence of the Practice of Physical Activity on the Self-Perceived Quality of Life of Women with Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Jul 2 [cited 2023 Nov 22];17(14):1–12. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32664375/.

- Aune D, Markozannes G, Abar L, Balducci K, Cariolou M, Nanu N, et al. Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Women With Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Jan 29];6(6). [CrossRef]

- Cormie P, Atkinson M, Bucci L, Cust A, Eakin E, Hayes S, et al. Clinical oncology society of australia position statement on exercise in cancer care. Medical Journal of Australia. 2018;209(4):184–7. [CrossRef]

- Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, Carmichael AR. Physical activity for women with breast cancer after adjuvant therapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 Jan 29;2018(1). [CrossRef]

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];51(11):2375–90. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31626055/.

- De Groef A, Geraerts I, Demeyer H, Van der Gucht E, Dams L, de Kinkelder C, et al. Physical activity levels after treatment for breast cancer: Two-year follow-up. Breast [Internet]. 2018 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];40:23–8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29674221/.

- Sheppard VB, Dash C, Nomura S, Sutton AL, Franco RL, Lucas A, et al. Physical activity, health-related quality of life, and adjuvant endocrine therapy-related symptoms in women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Nov 22];126(17):4059–66. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32614992/.

- Gavala-González J, Torres-Pérez A, Fernández-García JC. Impact of Rowing Training on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Levels in Female Breast Cancer Survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Nov 22];18(13). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34281126/.

- Sanft T, Harrigan M, Cartmel B, Ferrucci LM, Li FY, McGowan C, et al. Effect of healthy diet and exercise on chemotherapy completion rate in women with breast cancer: The Lifestyle, Exercise and Nutrition Early after Diagnosis (LEANer) study: Study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Nov 22];109. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34274495/.

- Dieli-Conwright CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Sami N, Lee K, Sweeney FC, et al. Aerobic and resistance exercise improves physical fitness, bone health, and quality of life in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res [Internet]. 2018 Oct 19 [cited 2024 Jan 29];20(1). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30340503/.

- Inam F, Bergin RJ, Mizrahi D, Dunstan DW, Moore M, Maxwell-Davis N, et al. Diverse strategies are needed to support physical activity engagement in women who have had breast cancer. Support Care Cancer [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];31(12). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37864656/.

- Murray J, Perry R, Pontifex E, Selva-Nayagam S, Bezak E, Bennett H. The impact of breast cancer on fears of exercise and exercise identity. Patient Educ Couns. 2022 Jul 1;105(7):2443–9. [CrossRef]

- Dennett AM, Peiris CL, Shields N, Morgan D, Taylor NF. Exercise therapy in oncology rehabilitation in Australia: A mixed-methods study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];13(5):e515–27. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28004526/.

- Trinh L, Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Crawford JJ, Courneya KS. Effects of supervised exercise on motivational outcomes in breast cancer survivors at 5-year follow-up. Eur J Oncol Nurs [Internet]. 2014 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];18(6):557–63. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25181937/.

- Uhm KE, Yoo JS, Chung SH, Lee JD, Lee I, Kim J Il, et al. Effects of exercise intervention in breast cancer patients: is mobile health (mHealth) with pedometer more effective than conventional program using brochure? Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2017 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];161(3):443–52. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27933450/.

- Rodríguez-Cañamero S, Cobo-Cuenca AI, Carmona-Torres JM, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, Santacruz-Salas E, Rabanales-Sotos JA, et al. Impact of physical exercise in advanced-stage cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med [Internet]. 2022 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];11(19):3714–27. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35411694/.

- Sotirova MB, McCaughan EM, Ramsey L, Flannagan C, Kerr DP, O’Connor SR, et al. Acceptability of online exercise-based interventions after breast cancer surgery: systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. 2021 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Nov 21];15(2):281–310. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32930924/.

- Stoica P, Söderström T. On the parsimony principle. Int J Control [Internet]. 1982 [cited 2024 Jan 29];36(3):409–18. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00207178208932904.

- Williams MN, Grajales CAG, Kurkiewicz D. Assumptions of Multiple Regression: Correcting Two Misconceptions. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation [Internet]. 2019 Nov 25 [cited 2024 Jan 29];18(1):11. Available online: https://openpublishing.library.umass.edu/pare/article/id/1435/.

- Garcia-Roca ME, Rodriguez-Arrastia M, Ropero-Padilla C, Hernando Domingo C, Folch-Ayora A, Temprado-Albalat MD, et al. Breast Cancer Patients’ Experiences with Online Group-Based Physical Exercise in a COVID-19 Context: A Focus Group Study. J Pers Med [Internet]. 2022 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Jan 29];12(3):356. [CrossRef]

- Weiner LS, Nagel S, Su · H Irene, Hurst S, Levy SS, Arredondo EM, et al. A remotely delivered, peer-led intervention to improve physical activity and quality of life in younger breast cancer survivors. J Behav Med [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 30];46:578–93. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert C, Twomey R, Bansal M, Rana B, Dhruva T, Livingston V, et al. The role of exercise for pain management in adults living with and beyond cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer 2023 31:5 [Internet]. 2023 Apr 11 [cited 2024 Jan 29];31(5):1–25. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00520-023-07716-4.

- Zawisza K, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, Nowak W, Kulig J, Jędrys J. Validity and reliability of the quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ C30) and its breast cancer module (EORTC QLQ BR23). Ginekol Pol [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2024 Jan 30];81(4):262–7. Available online: https://journals.viamedica.pl/ginekologia_polska/article/view/46482.

- Kshirsagar A, Wani S. Health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer surgery and undergoing chemotherapy in Ahmednagar district. J Cancer Res Ther [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Jan 29];17(6):1335–8. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/med/34916362.

- Ellingjord-Dale M, Vos L, Hjerkind KV, Hjartåker A, Russnes HG, Tretli S, et al. Alcohol, physical activity, smoking, and breast cancer subtypes in a large, nested case–control study from the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Program. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2017 Dec 1;26(12):1736–44. [CrossRef]

| In person n (%) |

Online n (%) |

Prescription n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±sd) | 46.1±8.7 | 49.0±8.9 | 50.1±7.9 | 48.6±8.6 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married or in a relationship | 14 (66.7) | 24 (77.4) | 17 (60.7) | 55 (68.8) |

| Separated or divorced | 2 (9.2) | 4 (12.9) | 5 (17.9) | 11 (13.8) |

| Single | 3 (14.3) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (21.4) | 11 (13.8) |

| Widowed | 2 (9.5) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.8) |

| Motherhood (yes) | 15 (71.4) | 25 (80.6) | 22 (78.6) | 62 (78.5) |

| Cohabitation | ||||

| No live alone | 18 (85.7) | 30 (96.8) | 24 (85.7) | 72 (90) |

| Live alone | 3 (14.3) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (14.3) | 8 (10) |

| Education Level | ||||

| Primary | 3 (14.4) | 6 (19.4) | 5 (17.9) | 14 (17.6) |

| Secondary | 9 (42.8) | 12 (38.7) | 14 (50.0) | 35 (43.8) |

| University | 9 (42.8) | 13 (41.9) | 9 (32.1) | 31 (38.8) |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Employed | 18 (85.7) | 23 (74.2) | 19 (67.9) | 60 (75.5) |

| Unemployed | 2 (9.5) | 5 (16.1) | 8 (28.6) | 15 (18.8) |

| Retired | 1 (4.8) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (6.3) |

| Income | ||||

| <1000 euros | 5 (23.8) | 13 (41.9) | 8 (28.6) | 26 (32.5) |

| 1000 - 2000 euros | 12 (57.1) | 15 (48.4) | 18 (64.3) | 45 (56.3) |

| >2000 euros | 4 (19.0) | 3 (9.7) | 2 (7.1) | 9 (11.3) |

| In person n (%) |

Online n (%) |

Prescription n (%) |

Total N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Type | ||||

| Luminal A | 7 (33.3) | 12 (38.7) | 10 (35.7) | 29 (36.3) |

| Luminal B (her2 +) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (12.9) | 5 (17.8) | 12 (15.0) |

| Luminal B (her2 -) | 9 (42.8) | 11 (35.4) | 10 (35.7) | 30 (37.5) |

| Non luminal | 1 (4.8) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (7.2) | 5 (6.2) |

| Triple negative | 1 (4.8) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.6) | 4 (5.0) |

| Treatment plan | ||||

| Adjuvant | 15 (71.4) | 21 (67.7) | 19 (67.9) | 55 (68.7) |

| Neoadjuvant | 6 (28.6) | 10 (32.3) | 7 (25.0) | 23 (28.8) |

| Surgery only | - | - | 2 (7.1) | 2 (2.5) |

| Laterality | ||||

| Right breast | 10 (47.6) | 10 (32.3) | 10 (35.7) | 30 (37.5) |

| Left breast | 9 (42.9) | 17 (54.8) | 17 (60.79 | 43 (53.8) |

| Bilateral | 2 (9.5) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (3.6) | 7 (8.7) |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| I | 5 (23.8) | 9 (29.0) | 13 (46.4) | 27 (33.8) |

| II | 11 (52.4) | 20 (64.5) | 12 (42.9) | 43 (53.8) |

| III | 3 (14.3) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (6.2) |

| IV | 2 (9.5) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (7.1) | 5 (6.2) |

| Treatment during the study | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 14 (66.7) | 16 (51.6) | 17 (60.7) | 47 (58.8) |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (9.5) | 4 (13.0) | 2 (7.1) | 8 (10.0) |

| Hormonotherapy | 5 (23.8) | 11 (35.5) | 9 (32.2) | 25 (31.2) |

| Prescribed treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 18 (85.7) | 20 (64.5) | 18 (64.3) | 56 (70.9) |

| Radiotherapy | 16 (76.2) | 25 (80.6) | 27 (96.4) | 68 (85.0) |

| Hormonotherapy | 18 (85.7) | 25 (80.6) | 25 (89.3) | 68 (85.0) |

| Groups | Basal | 24 weeks | P Value/ d Cohen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Health | ||||

| Total | 70.63 (±16.96) | 77.25(±14.29)* | <0.001/0.53 | |

| In person | 75.14 ( ±13.26) | 81.71(±13.67)* | 0.02/ 0.55 | |

| Online | 69.35( ±16.40) | 77.27(±13.83)* | 0.005 / 0.60 | |

| Prescription | 68.64 ( ±19.77) | 72.95(±14.72) | ||

| Dimensions | ||||

| Physical Functioning | Total | 34.01 ( ±10.44) | 34.20 ( ±11.93) | |

| In person | 30.24 ( ±6.01) | 30.48( ±4.71) | ||

| Online | 36.77 ( ±12.01) | 33.08 ( ±10.87) | ||

| Prescription | 39.09 ( ±10.59) | 33.75 ( ±16.08) | ||

| Daily Activities | Total | 43.40 ( ±19.92) | 37.67 ( ±16.28)* | |

| In person | 35.76 ( ±14.41) | 33.19 ( ±12.78) | <0.001/0.37 | |

| Online | 47.32 ( ±19.87) | 37.54 ( ±15.81) | 0.014/ 0.47 | |

| Prescription | 44.79 ( ±22.43) | 42.09 ( ±19.10) | ||

| Social | Total | 50.30 ( ±21.93) | 44.84 ( ±22.94)* | 0.018/0.35 |

| In person | 50.76 ( ±22.85) | 45.95 ( ±19.87) | ||

| Online | 53.74 ( ±22.41) | 47.69 ( ±23.98) | ||

| Prescription | 46.14 ( ±20.75) | 40.41 ( ±24.72) | ||

| Emotional | Total | 47.91 ( ±17.95) | 43.84 ( ±18.26)* | 0.014/0.26 |

| In person | 53.43 ( ±16.54) | 51.90 ( ±19.33) | ||

| Online | 49.29 ( ±21.97) | 39.73 ( ±15.41)* | 0.019/0.53 | |

| Prescription | 42.25 ( ±13.68) | 41.01 ( ±18.62) | ||

| cognitive | Total | 43.28 ( ±17.60) | 43.09 ( ±18.67) | |

| In person | 41.76 ( ±15.43) | 41.06 ( ±16.54) | ||

| Online | 44.13 ( ±15.82) | 42.04 ( ±17.33) | ||

| Prescription | 45.59 ( ±22.37) | 43.89 ( ±21.15) | ||

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fatigue | Total | 51.31 ( ±18.56) | 46.49 ( ±14.61)* | 0.007/0.31 |

| In person | 47.14 ( ±14.27) | 45.19 ( ±9.34) | ||

| Online | 54.74 ( ±20.22) | 45.54 ( ±14.07) | ||

| Prescription | 50.64 ( ±19.37) | 48.86 ( ±19.07) | ||

| Pain | Total | 46.69 ( ±19.20) | 46.75 ( ±16.72) | |

| In person | 41.24 ( ±13.86) | 43.67 ( ±14.62) | ||

| Online | 52.52 ( ±22.44) | 47.35 ( ±13.81) | ||

| Prescription | 44.32 (±17.56) | 49.01 ( ±31.42) | ||

| Nausea and Vomiting | Total | 33.10 (±12.74) | 26.86 (±6.27)* | <0.001/0.52 |

| In person | 30.43 (±9.39) | 26.24 (±3.91) | ||

| Online | 37.68 (±15.25) | 27.42 (±8.75)* | 0.009/0.71 | |

| Prescription | 30.04 (±10.58) | 26.77 (±4.56) | ||

| Shortness of breath | Total | 30.94 (±12.73) | 31.01 (±13.27) | |

| In person | 29.76 (±10.06) | 29.29 (±10.52) | ||

| Online | 33.06 (±16.31) | 28.85 (±9.19) | ||

| Prescription | 29.46 (±9.75) | 35.23 (±18.35) | ||

| insomnia | Total | 53.75 (±25.50) | 56.88 (±24.96) | |

| In person | 59.52 (±27.92) | 63.10 (±23.21) | ||

| Online | 54.84 (±26.94) | 53.85 (±24.18) | ||

| Prescription | 48.21 (±21.44) | 54.55 (±27.43) | ||

| Loss of appetite | Total | 35.94 (±18.16) | 28.99 (±11.03)* | 0.005/0.32 |

| In person | 33.33 (±12.07) | 29.76 (±10.06) | ||

| Online | 39.52 (±21.18) | 26.92 (±6.79)* | 0.013/0.55 | |

| Prescription | 33.93 (±18.27) | 30.68 (±15.29) | ||

| Constipation | Total | 45.63 (±26.91) | 33.33 (±16.42)* | <0.001/0.47 |

| In person | 40.48 (±24.33) | 29.76 (±12.79) * | 0.002/0.45 | |

| Online | 50.81 (±29.21) | 36.54 (±20.28)* | 0.002/0.56 | |

| Prescription | 43.75 (±26.02) | 32.95 (±14.19) | ||

| Diarrhea | Total | 31.25 (±15.15) | 28.62 (±9.85) | |

| In person | 30.95 (±13.47) | 28.57 (±8.96) | ||

| Online | 29.03 (±9.35) | 29.81 (±12.28) | ||

| Prescription | 33.93 (±20.65) | 27.27 (±7.35) | ||

| Financial impact | Total | 40.31 (±24.03) | 41.30 (±24.94) | |

| In person | 34.52 (±18.50) | 42.86 (±27.54) | ||

| Online | 46.77 (±27.94) | 44.23 (±25.79) | ||

| Prescription | 37.50 (±22.04) | 36.36 (±21.44) |

| Alfa de Cronbach | |

|---|---|

| Global Health | 0.898 |

| Physical Functioning | 0.762 |

| Daily Activities | 0.829 |

| Social | 0.906 |

| Emotional | 0.886 |

| Cognitive | 0.877 |

| Model | R2 Adjusted | Standard Error |

F (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dependent Variable: Global Health Scale at 24 weeks into the program Covariates: Tumor type. Chemotherapy and Type of physical exercise program |

0.503 | 9.710 | 14.515(<0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).