Submitted:

02 February 2024

Posted:

05 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Positive Experience Design

2.2. Product Attachment

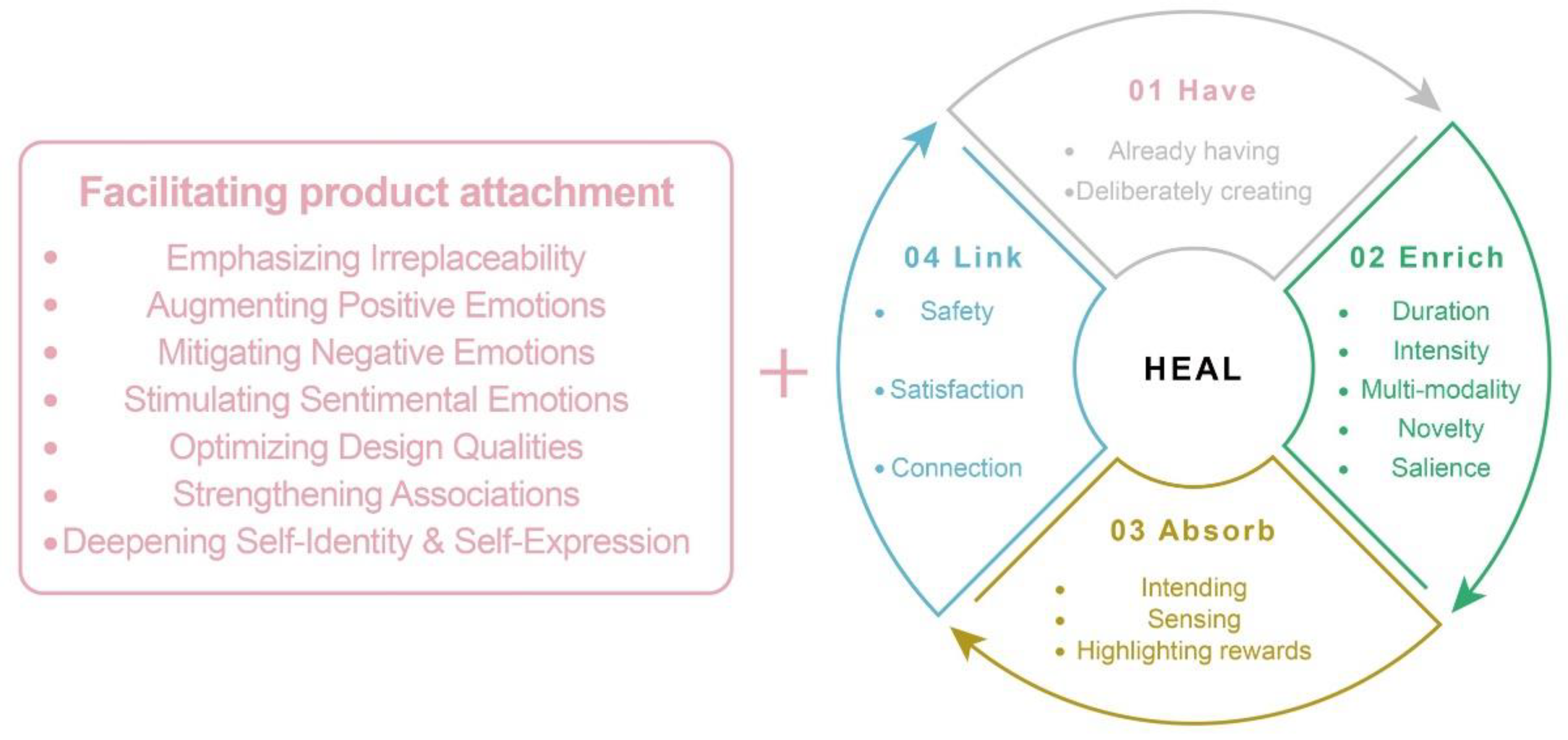

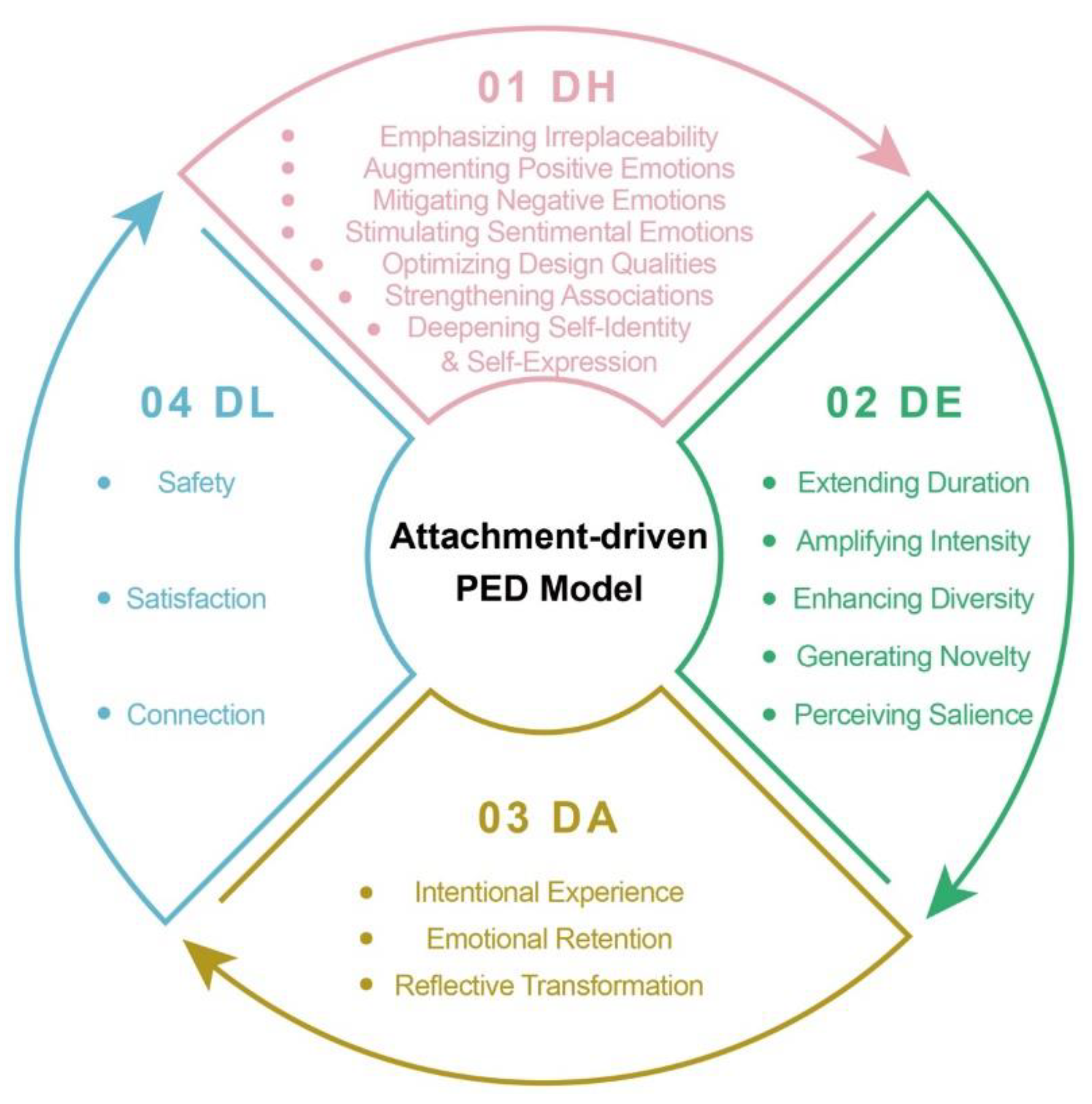

3. Construction of Design Model

3.1. Construction Process

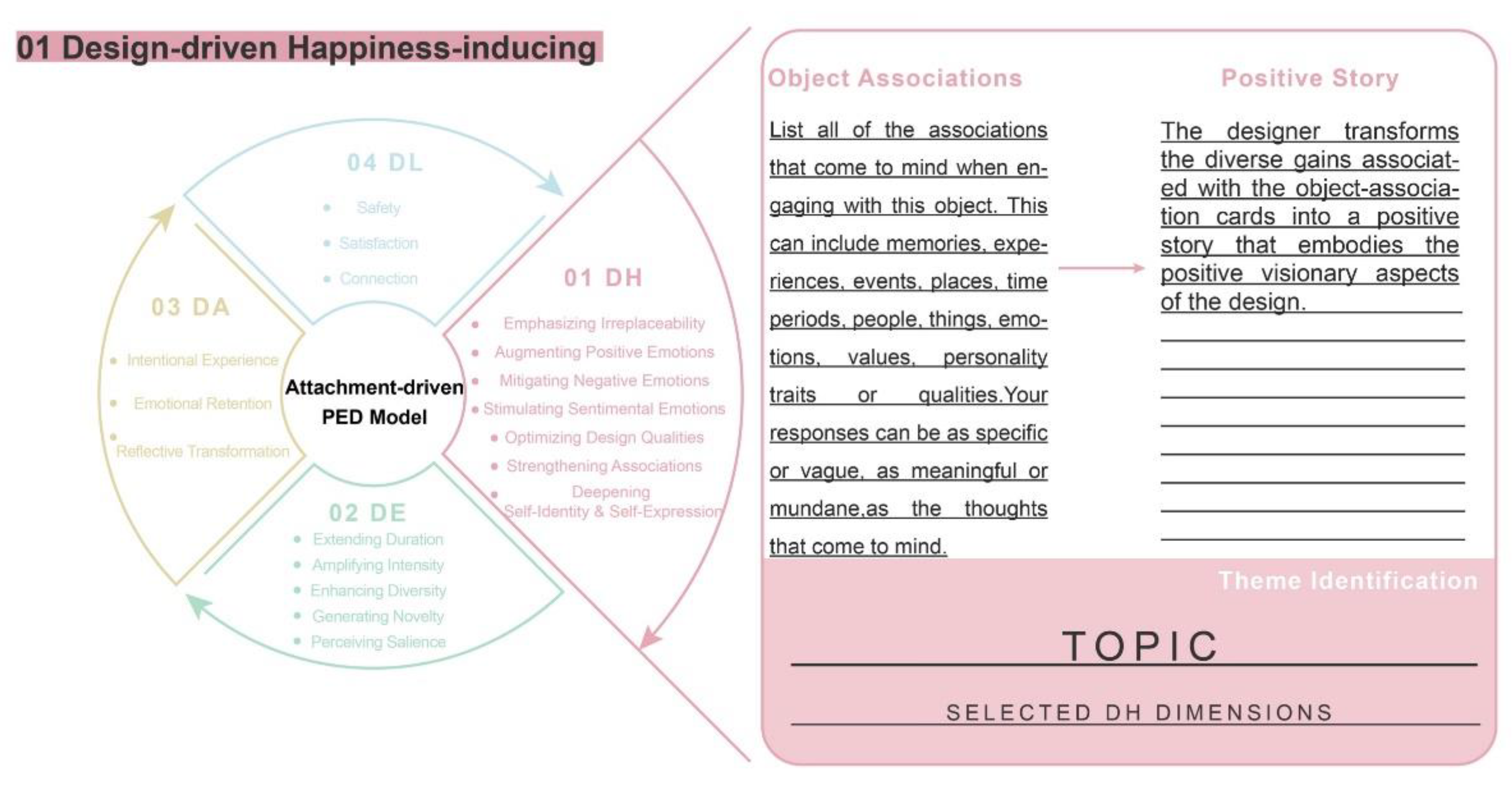

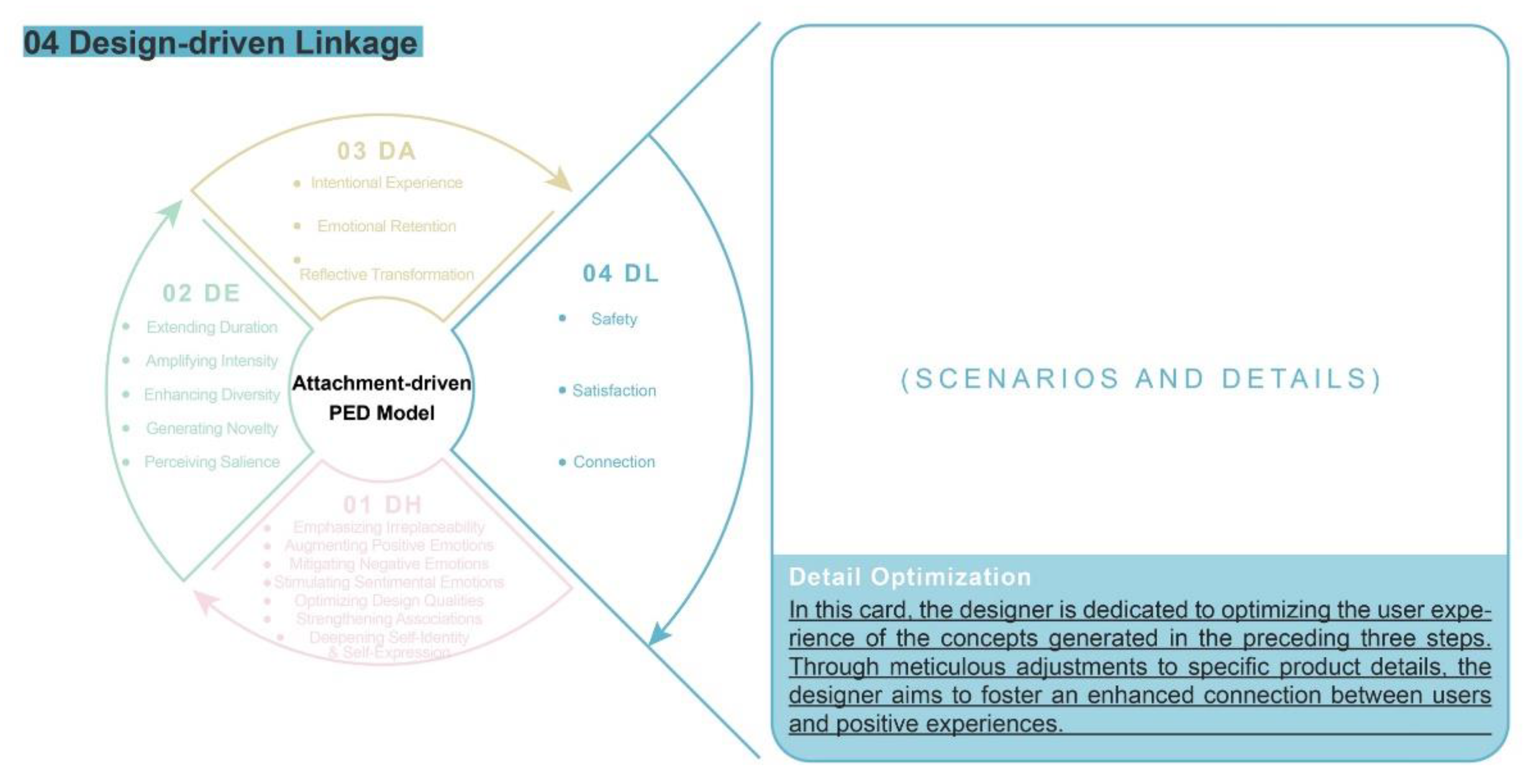

3.1.1. Design-Driven Happiness-Inducing Phase

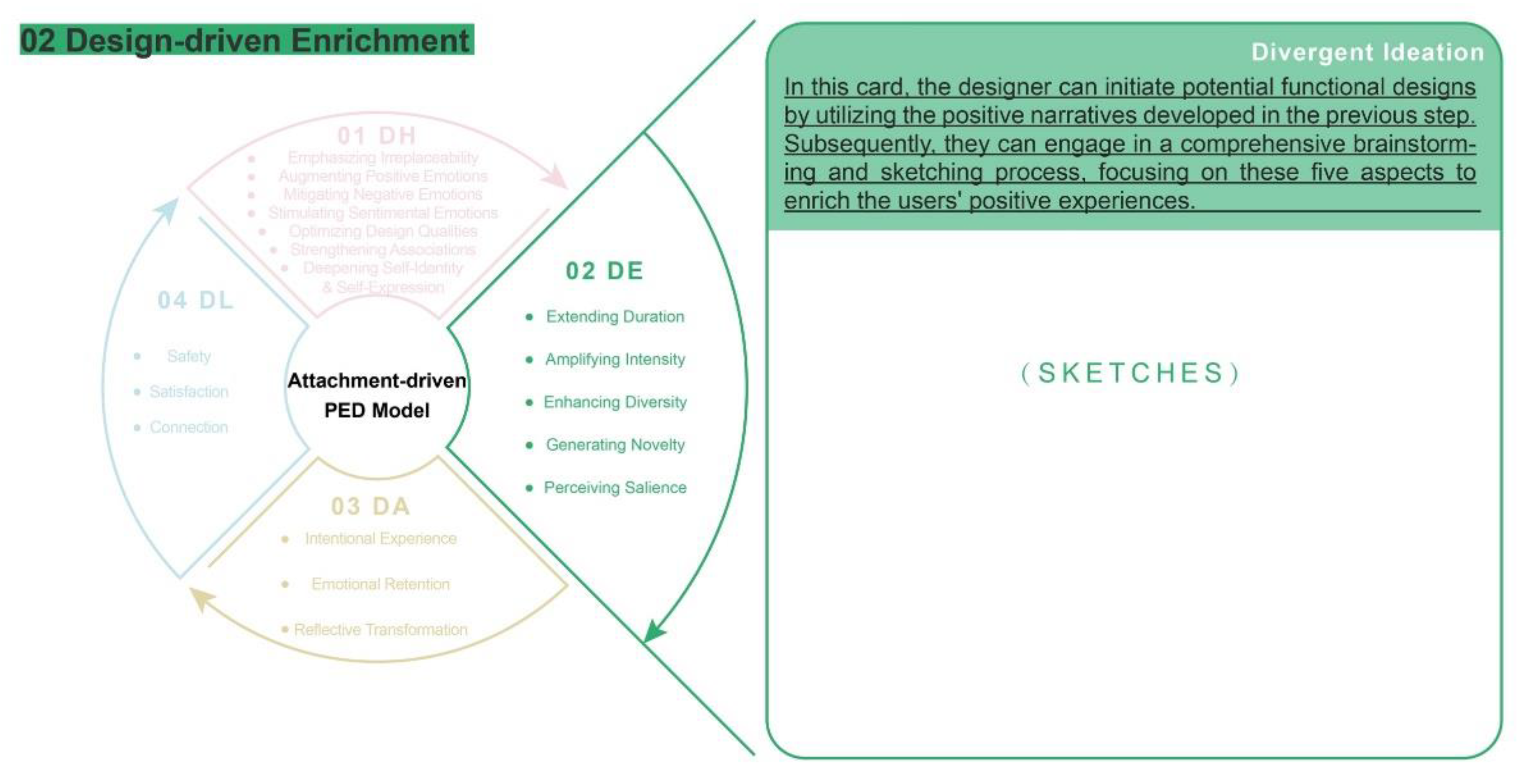

3.1.2. Design-Driven Enrichment Phase

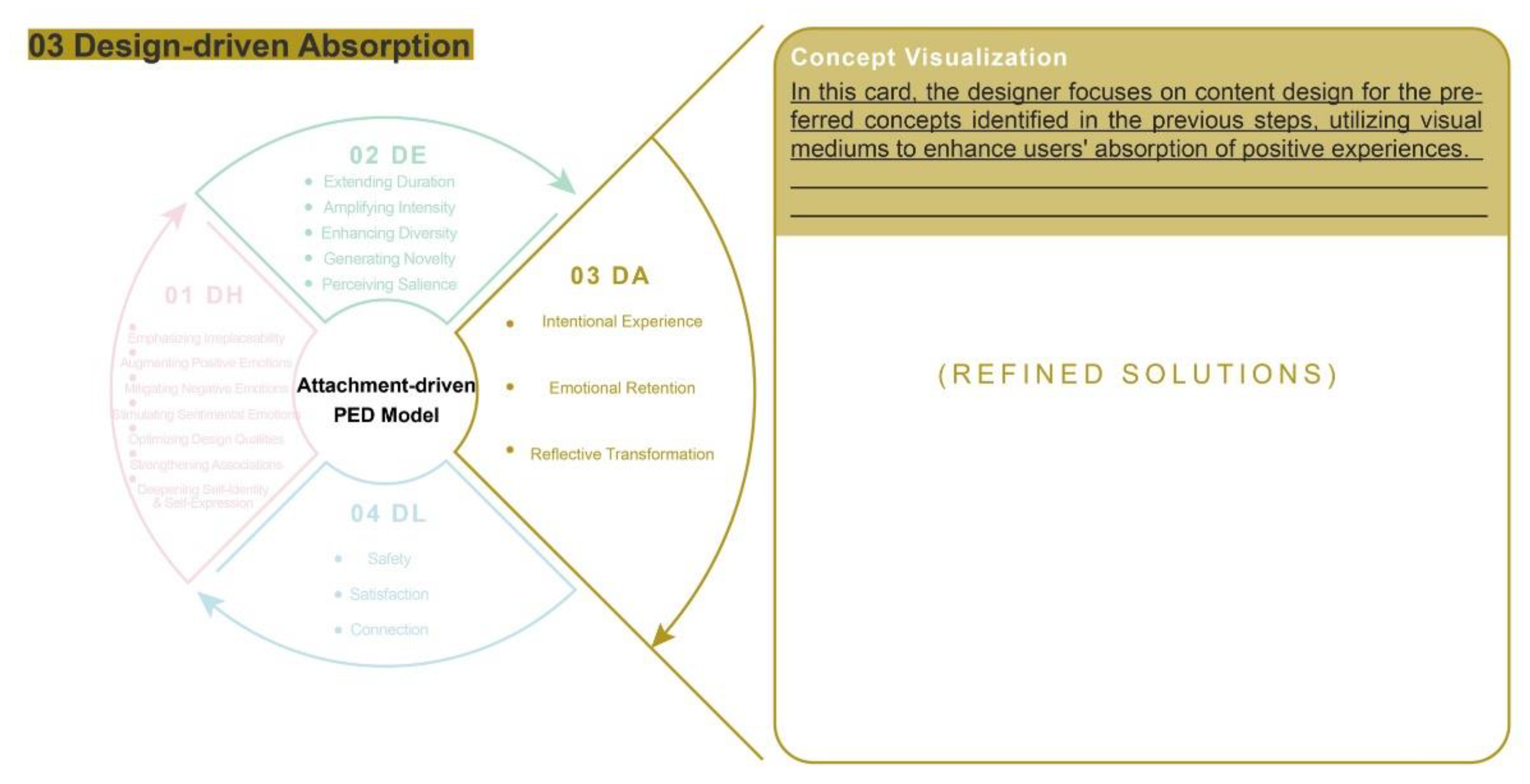

3.1.3. Design-Driven Absorption Phase

3.1.4. Design-Driven Linkage Phase

3.2. Design Algorithm

4. Design Workshop

4.1. Participants

4.2. Materials

4.3. Procedure

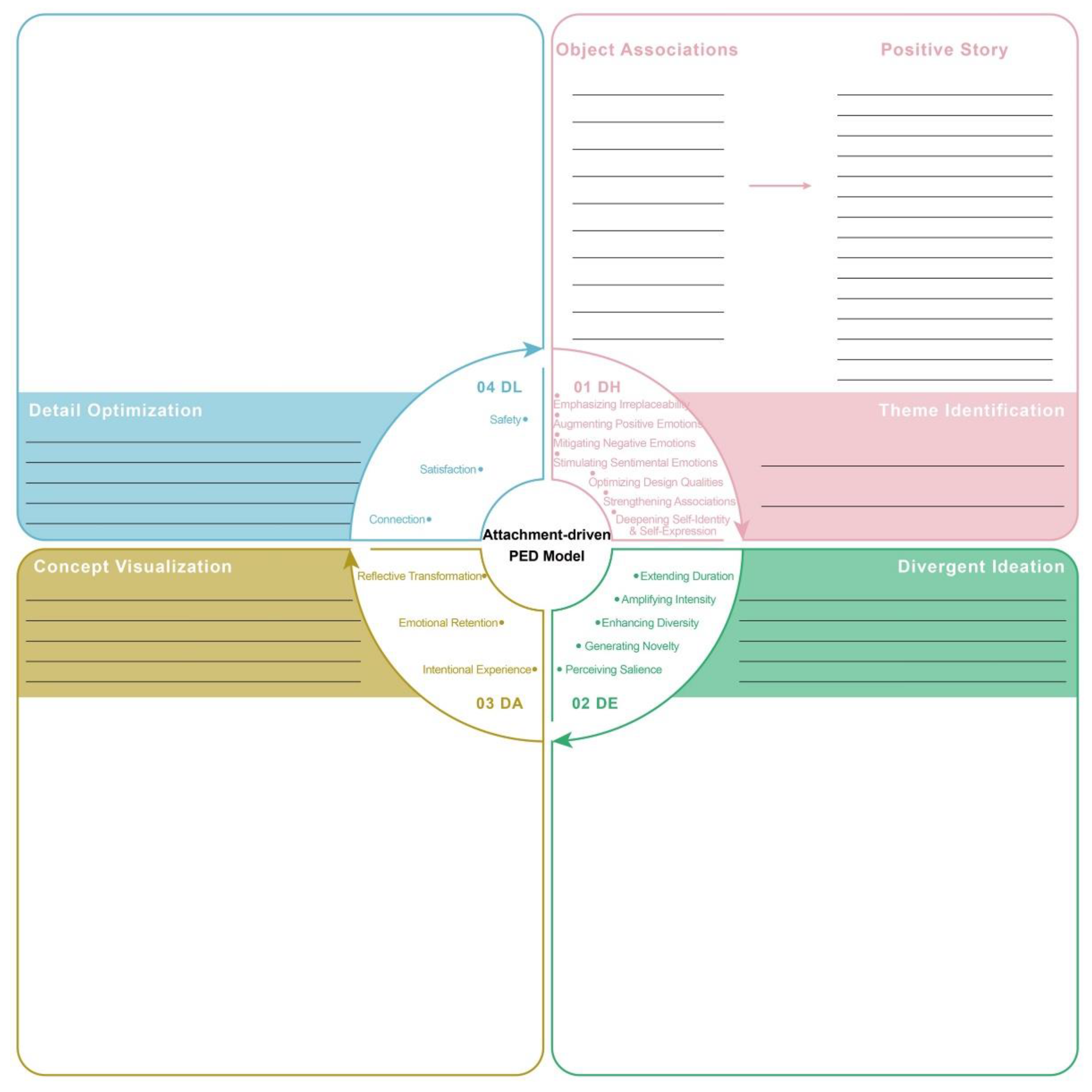

- DH phase: Each of the 11 groups conducted on-site research at the Shanghai Astronomy Museum to identify experiences that could evoke emotional attachment. They then summarised their findings and completed object association cards [35]. Following that, the participants engaged in group discussions, focusing on the selected design granularity and the object association cards. They were tasked with combining existing technologies to articulate positive stories that drive user experiences and refine their topic direction;

- DE phase: Participants developed concept proposals and explored functionality and interaction based on the selected topic direction and five levels of design granularity. The aim was to enrich positive user experiences and generate multiple concept proposals;

- DA phase: Group members enhanced the relevance of each concept proposal to the Astronomy Museum experience through three levels of design attention. Subsequently, they visually expressed the preferred concept proposals as a group, aiming to stimulate user absorption of positive experiences through product attachment;

- DL phase: Group members considered the practical application scenarios and consumer behaviour of the design proposals to optimise the product experience details. They evaluated whether the product contributed to the three levels of design attention from the user’s perspective (DL) and refined the design proposals and user interaction experience details in the usage context to strengthen attachment.

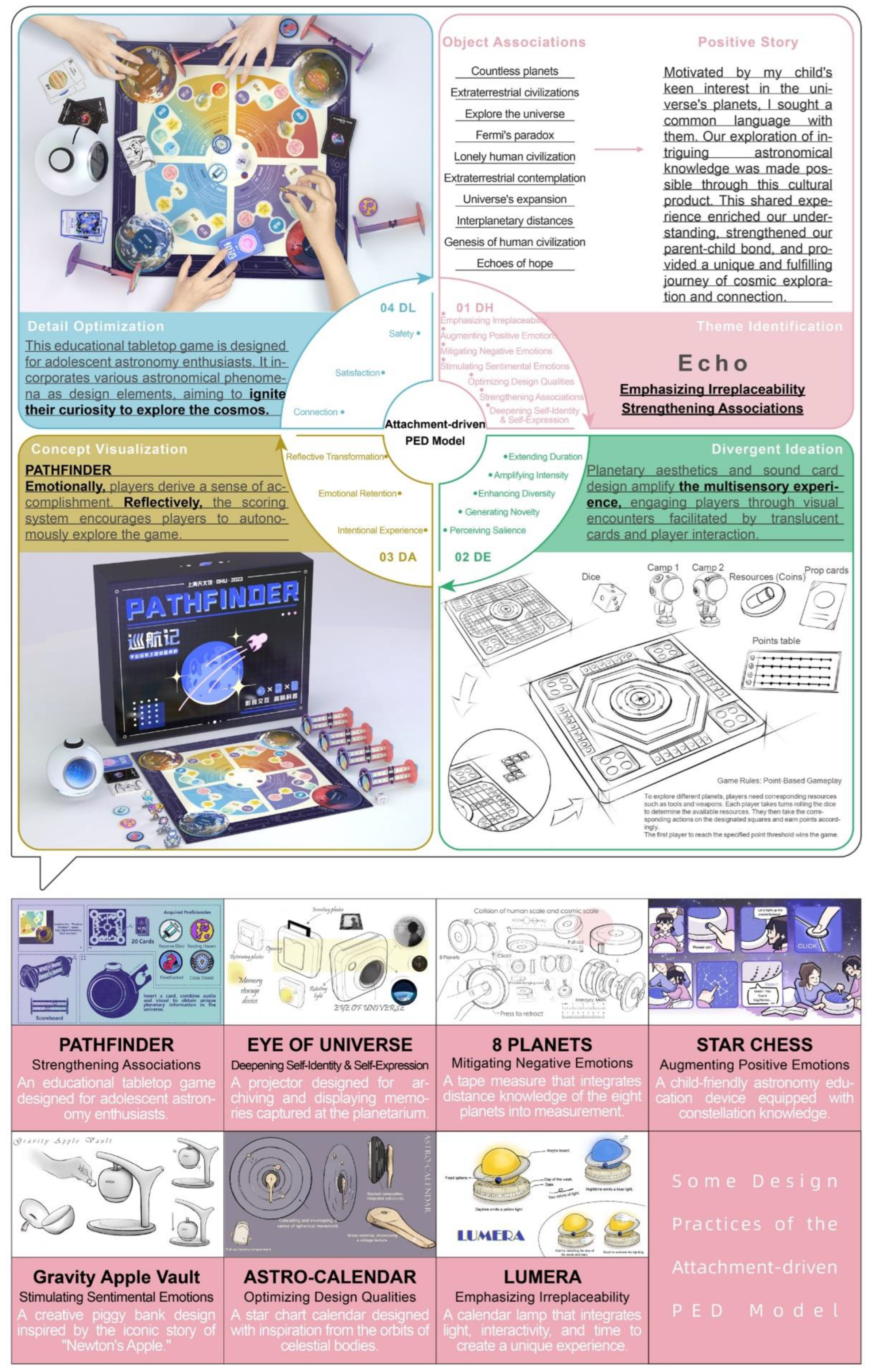

4.4. Design Outputs

5. Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, E.; Duan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Peng, H.; Hu, W. Exploring the positive user experience possibilities based on product emotion theory: A beverage unmanned retail terminal case. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 889664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Pohlmeyer, A.E. Positive design: An introduction to design for subjective well-being. Int. J. Des. 2013, 7, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P.M.A. Faces of product pleasure: 25 positive emotions in human-product interactions. Int. J. Des. 2012, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wu, C.; Spence, C. Multisensory perception and positive emotion: Exploratory study on mixed item set for apparel e-customisation. Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 2046–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, C.; Spence, C. Comparing the influence of visual information and the perceived intelligence of voice assistants when shopping for sustainable clothing online. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, L.; Pohlmeyer, A.E.; Hekkert, P. Design for sustained wellbeing through positive activities—A multi-stage framework. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R. Hardwiring happiness: The new brain science of contentment, calm, and confidence; Harmony: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, R.; Shapiro, S.; Hutton-Thamm, E.; Hagerty, M.R.; Sullivan, K.P. Learning to learn from positive experiences. J. Posit. Psychol. 2023, 18, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.R.A.; Prybutok, V.R.; Peak, D.A.; Torres, R.; Pavur, R.J. The role of emotional attachment in IPA continuance intention: An emotional attachment model. Inform. Technol. Peopl. 2023, 36, 867–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClay, M.; Sachs, M.E.; Clewett, D. Dynamic emotional states shape the episodic structure of memory. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Gong, Y.; Gursoy, D. Antecedents of trust and adoption intention toward artificially intelligent recommendation systems in travel planning: A heuristic—Systematic model. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1714–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.H. Systemic design principles for complex social systems. In Social systems and design; Metcalf, G.S., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, JPN, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 91–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Hao, Y.; Yoon, J. Purpal: An interactive box that up-regulates positive emotions in consumption behaviors. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25 April 2020; pp. 1–6.

- Norman, D.A. The way I see it memory is more important than actuality. Interactions 2009, 16, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J. Designing for the self: Making products that help people become the person they desire to be. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 04 April 2009; pp. 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P.; Fokkinga, S. Beyond Maslow’s Pyramid: Introducing a typology of thirteen fundamental needs for human-centered design. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. Product Service and Positive Experience Design; China Textile Press: Beijing, PRC, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, P. An impact-centered, sustainable, positive experience design model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ge, Y.; Li, N. An eye tracking study: Positive emotional interface design facilitates learning outcomes in multimedia learning? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 2021, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.; De Guzman, R.G. Effectiveness of taking in the good based-bibliotherapy intervention program among depressed Filipino female adolescents. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2016, 23, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A.; Simpson, J.A.; Berlin, L.J. Taking perspective on attachment theory and research: Nine fundamental questions. Attachment & Human Development 2022, 24, 543–560. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Product attachment: Design strategies to stimulate the emotional bonding to products. In Product Experience; Schifferstein, H.N.J., Hekkert, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, NL, 2008; Volume 17, pp. 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.H.; Hansen, H.W.; Laursen, L.N. Designing long-lasting interior products: Emotional attachment, product positioning and uniqueness. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graul, A.R.H.; Brough, A.R.; Isaac, M.S. How emotional attachment influences lender participation in consumer-to-consumer rental platforms. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Jiang, M.; Li, Y.N.; Li, W.; Mead, J.A. The impact of product defect severity and product attachment on consumer negative emotions. Psychol. Market. 2023, 40, 1026–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, M.F.; Costa, J.M.H.; Pigosso, D.C.A. How are emotional attachment strategies currently employed in product-service system cases? A systematic review underscoring drivers and hindrances. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED23), Bordeaux, France, 24 28 July 2023; pp. 2095–2104. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, R.; Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Schoormans, J.P.L. A longitudinal study of product attachment and its determinants. In European Advances in Consumer Research; Ekstrom, K.M., Brembeck, H., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2005; Volume 7, pp. 641–647. [Google Scholar]

- Agost, M.J.; Vergara, M. Principles of affective design in consumers’ response to sustainability design strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, L.M.; Min, S. Product experiences of clothing attachment in baby boomers in the United States. Fash. Text. 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Noriuchi, M.; Isobe, H.; Shirato, M.; Hirao, N. Neural correlates of product attachment to cosmetics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, M.C.; Yoon, J. I love it, I’ll never use it: Exploring factors of product attachment and their effects on sustainable product usage behaviors. Int. J. Des. 2022, 16, 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Page, T. Product attachment and replacement: Implications for sustainable design. Int. J. Sust. Design 2014, 2, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; Deary, I.J.; Whiteman, M.C. Personality traits; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E.; Rochford, K.; Taylor, S.N. The role of the positive emotional attractor in vision and shared vision: Toward effective leadership, relationships, and engagement. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, D.; Thurgood, C.; van den Hoven, E. Designing objects with meaningful associations. Int. J. Des. 2018, 12, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Gadd, M.; Chapman, J.; Lloyd, P.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D. Emotional durability design nine—A tool for product longevity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudai, Y.; Karni, A.; Born, J. The Consolidation and transformation of memory. Neuron 2015, 88, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.M. Measuring usability with the use questionnaire. Usability interface 2001, 8, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Bilro, R.G.; Japutra, A. The effect of consumer-generated media stimuli on emotions and consumer brand engagement. J. Prod. Brand. 2020, 29, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R.; Boateng, H.; Renner, A.; Kosiba, J.P.B. Antecedents and consequences of customer engagement on Facebook: An attachment theory perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sub-directions | Authors | Year | Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoting positive perceptions | Norman [14] | 2009 | This study highlighted the importance of memory over actuality and urged to design for memory in enhancing positive experiences. |

| Zimmerman [15] | 2009 | The study proposed the application of attachment theory to the interaction design of products to effectively help people become the person they desire to be. | |

| Desmet et al. [16] | 2020 | A design-focused typology of psychological human needs was introduced, serving as a comprehensive repository of needs for user-centred design research. | |

| Enriching positive experiences | Wu [17] | 2022 | Several detailed models and pathways for PED were proposed based on extensive research in product service design. |

| Wu et al. [18] | 2023 | An impact-centred, sustainable, PED model was formulated to empower designers in generating design concepts with enduring impact. | |

| Improving user behaviour | Wiese et al. [6] | 2020 | A multi-stage design framework model was devised to leverage technology and guide the IT industry in designing activities that fostered sustained well-being. |

| Peng et al. [19] | 2021 | Eye-tracking experiments showed that local positive emotion interface design improved learning effectiveness over holistic and neutral layouts. | |

| Cultivating positive thinking | Hanson [7] | 2013 | The book integrated insights from modern neuroscience, positive psychology, evolutionary biology and clinical practice, resulting in the HEAL framework for internalising positive experiences. |

| Jacob [20] | 2016 | The application of the HEAL framework in the intervention of depression treatment for adolescent girls demonstrated its positive effect on therapy. | |

| Hanson [8] | 2023 | The study explored the utility of the HEAL framework in creating the TGC course and emphasised its contribution to improving intrinsic strength, as assessed through comprehensive self-report measures. |

| Attachment Factors | Dimensions of DH | Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Irreplaceability1 | Emphasising Irreplaceability | Design is intimately associated with special significance, leading users to perceive it as irreplaceable. |

| Positive Emotions1 | Augmenting Positive Emotions | User-design interactions have the potential to enhance positive emotional perceptions, including happiness, enjoyment and satisfaction. |

| Negative Emotions1 | Mitigating Negative Emotions | User-design interactions can also alleviate or eliminate negative emotional perceptions, such as disappointment, guilt and fear. |

| Sentimental Emotions1 | Stimulating Sentimental Emotions | Design stimulates users to experience a rich array of emotional perceptions, often intertwined with sentimentality, loss and sadness. |

| Design & Material Qualities1 | Optimising Design Qualities | The aesthetic value and material quality of the design engender a sense of value and even surpass users’ expectations. |

| Active Associations to People & Relatedness1 | Strengthening Associations | The design facilitates the establishment and consolidation of connections between users and others, encompassing sharing, collaboration and a sense of belonging. |

| Self-Identity & Self-Expression1 | Deepening Self-Identity & Self-Expression | Design serves as a means for users to express their individuality and can elicit a sense of identity. |

| Memory Retention Factors | Dimensions of DE | Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Duration* | Extending Duration | Product experience perception is prolonged in duration and frequency. |

| Intensity* | Amplifying Intensity | Product experience perception is intensified, deepening impressions. |

| Multi-modality* | Enhancing Diversity | Product experience perception is diversified, creating a sense of immersion. |

| Novelty* | Generating Novelty | Product experience perception incorporates unexpected or surprising elements. |

| Salience* | Perceiving Salience | Product experience perception enhances self-connection in expression. |

| Absorption Factors | Dimensions of DA | Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Intending* | Intentional Experience | Creating distinctive imagery based on culture, history, audio-visual symbols, etc., to foster immersive or conscious experiences for users. |

| Sensing* | Emotional Retention | Enhancing emotional connection and retention through interactive user engagement. |

| Highlighting rewards * | Reflective Transformation | Encouraging user reflection and facilitating cognitive and behavioural changes through philosophical concepts. |

| Linkage Dimensions | Dimensions of DL | Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| Safety* | Safety | Integrating the product into the user experience to enhance safety by avoiding harm. |

| Satisfaction* | Satisfaction | Integrating the product into the user experience to increase satisfaction by approaching rewards. |

| Connection* | Connection | Integrating the product into the user experience enhances the sense of connection by attaching to others. |

| Phases | Sub-objectives | Design Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| DH | Theme Identification | Emphasising Irreplaceability (X11), Augmenting Positive Emotions (X12), Mitigating Negative Emotions (X13), Stimulating Sentimental Emotions (X14), Optimising Design Qualities (X15), Strengthening Associations (X16), Deepening Self-Identity & Self-Expression (X17) |

| DE | Divergent Ideation | Extending Duration (X21), Generating Novelty (X22), Enhancing Diversity (X23), Perceiving Salience (X24), Amplifying Intensity (X25) |

| DA | Concept Visualisation | Reflective Transformation (X31), Emotional Retention (X32), Intentional Experience (X33) |

| DL | Detail Optimisation | Safety (X41), Satisfaction (X42), Connection (X43) |

| Number | Items | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Cronbach’s Alpha | KMO Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usefulness | 5.202 | 1.242 | 0.853 | 0.744 | |

| UU1 | It helps me be more effective. | 5.353 | 1.098 | ||

| UU2 | It helps me be more productive. | 5.206 | 1.008 | ||

| UU3 | It is useful. | 5.971 | 0.937 | ||

| UU4 | It gives me more control over the activities in my life. | 5.088 | 1.240 | ||

| UU5 | It makes the things I want to accomplish easier to get done. | 5.147 | 1.234 | ||

| UU6 | It saves me time when I use it. | 5.000 | 1.155 | ||

| UU7 | It meets my needs. | 5.324 | 1.147 | ||

| UU8 | It does everything I would expect it to do. | 4.529 | 1.637 | ||

| Ease of use | 4.727 | 1.426 | 0.909 | 0.785 | |

| UE1 | It is easy to use. | 4.971 | 1.403 | ||

| UE2 | It is simple to use. | 4.794 | 1.366 | ||

| UE3 | It is user-friendly. | 5.265 | 1.377 | ||

| UE4 | It requires the fewest steps possible to accomplish what I want to do with it. | 5.147 | 1.234 | ||

| UE5 | It is flexible. | 4.853 | 1.329 | ||

| UE6 | Using it is effortless. | 4.353 | 1.574 | ||

| UE7 | I can use it without written instructions. | 3.647 | 1.390 | ||

| UE8 | I do not notice any inconsistencies as I use it. | 4.735 | 1.421 | ||

| UE9 | Both occasional and regular users would like it. | 4.706 | 1.426 | ||

| UE10 | I can recover from mistakes quickly and easily. | 4.912 | 1.264 | ||

| UE11 | I can use it successfully every time. | 4.606 | 1.391 | ||

| Ease of learning | 4.691 | 1.401 | 0.891 | 0.822 | |

| UL1 | I learned to use it quickly. | 4.676 | 1.532 | ||

| UL2 | I easily remember how to use it. | 4.412 | 1.373 | ||

| UL3 | It is easy to learn to use it. | 4.853 | 1.374 | ||

| UL4 | I quickly became skilful with it. | 4.824 | 1.336 | ||

| Satisfaction | 5.244 | 1.292 | 0.919 | 0.843 | |

| US1 | I am satisfied with it. | 5.382 | 1.206 | ||

| US2 | I would recommend it to a friend. | 5.382 | 1.280 | ||

| US3 | It is fun to use. | 5.206 | 1.095 | ||

| US4 | It works the way I want it to work. | 4.853 | 1.282 | ||

| US5 | It is wonderful. | 5.118 | 1.452 | ||

| US6 | I feel I need to have it. | 5.265 | 1.421 | ||

| US7 | It is pleasant to use. | 5.500 | 1.285 | ||

| Overall reliability of the questionnaire, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, is 0.953 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).