Submitted:

05 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A.

- Identity the types of tobacco control health communication interventions in Africa

- B.

- Identify how young people are being involved in tobacco control health communication

2. Method

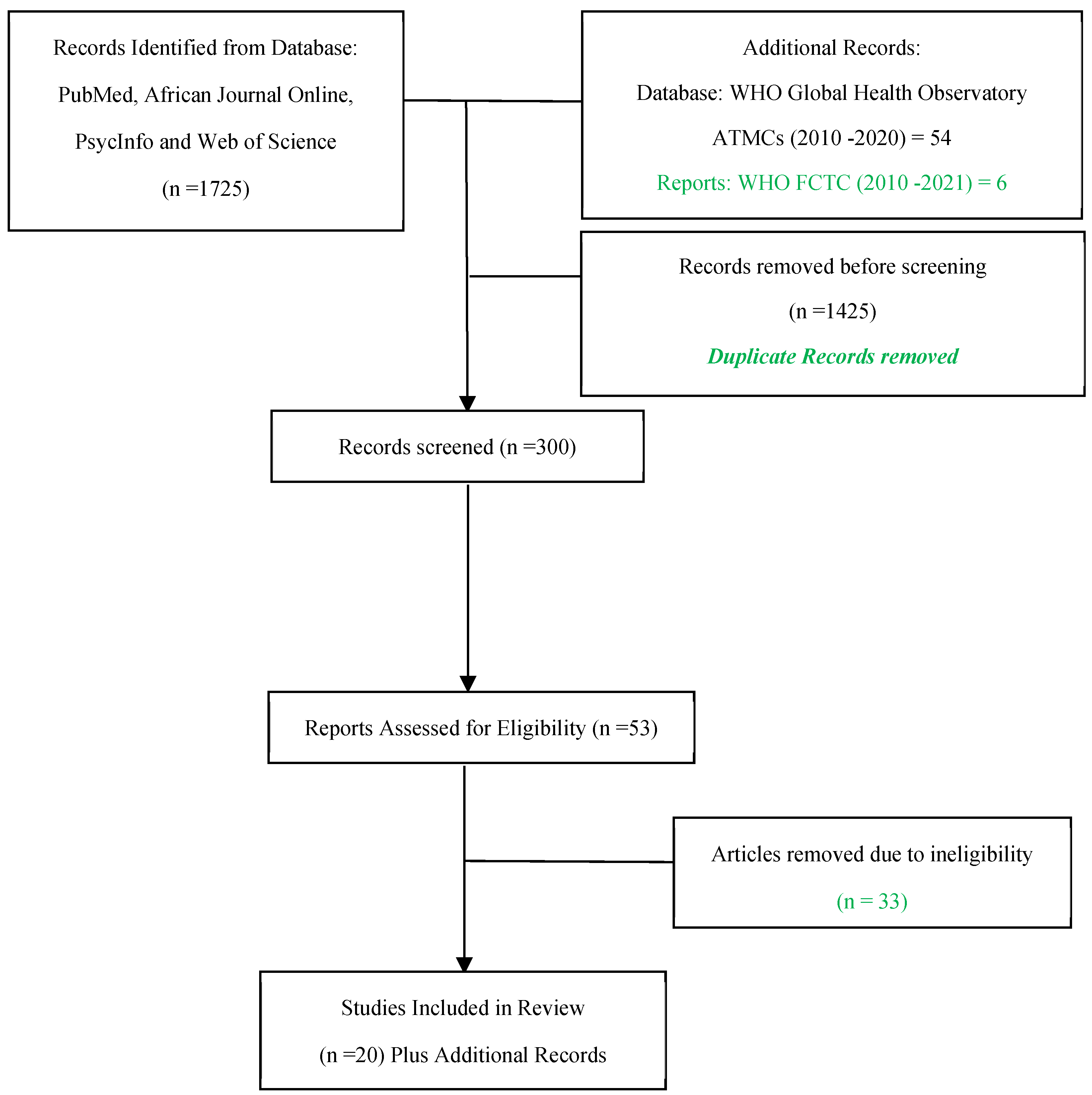

2.1. Data Sources and Identification

2.2. Eligibility Criteria (PICo)

- A.

- Interpersonal communication

- B.

- Mass media and new media communication

- C.

- Community mobilization and citizen engagement

- D.

- Professional medical communications

- E.

- Constituency relations and strategic partnerships in health communication

- F.

- Policy communication and public advocacy

2.3. Search Approach and Characteristics of Sources

A. Database: The WHO GHO ATMCs data for 54 African countries from 2010 – 2020

B. Reports: Six reports from the WHO FCTC Global Progress Report on Article 12 from 2010 – 2021

2.4. Data Charting Process and Items

- A.

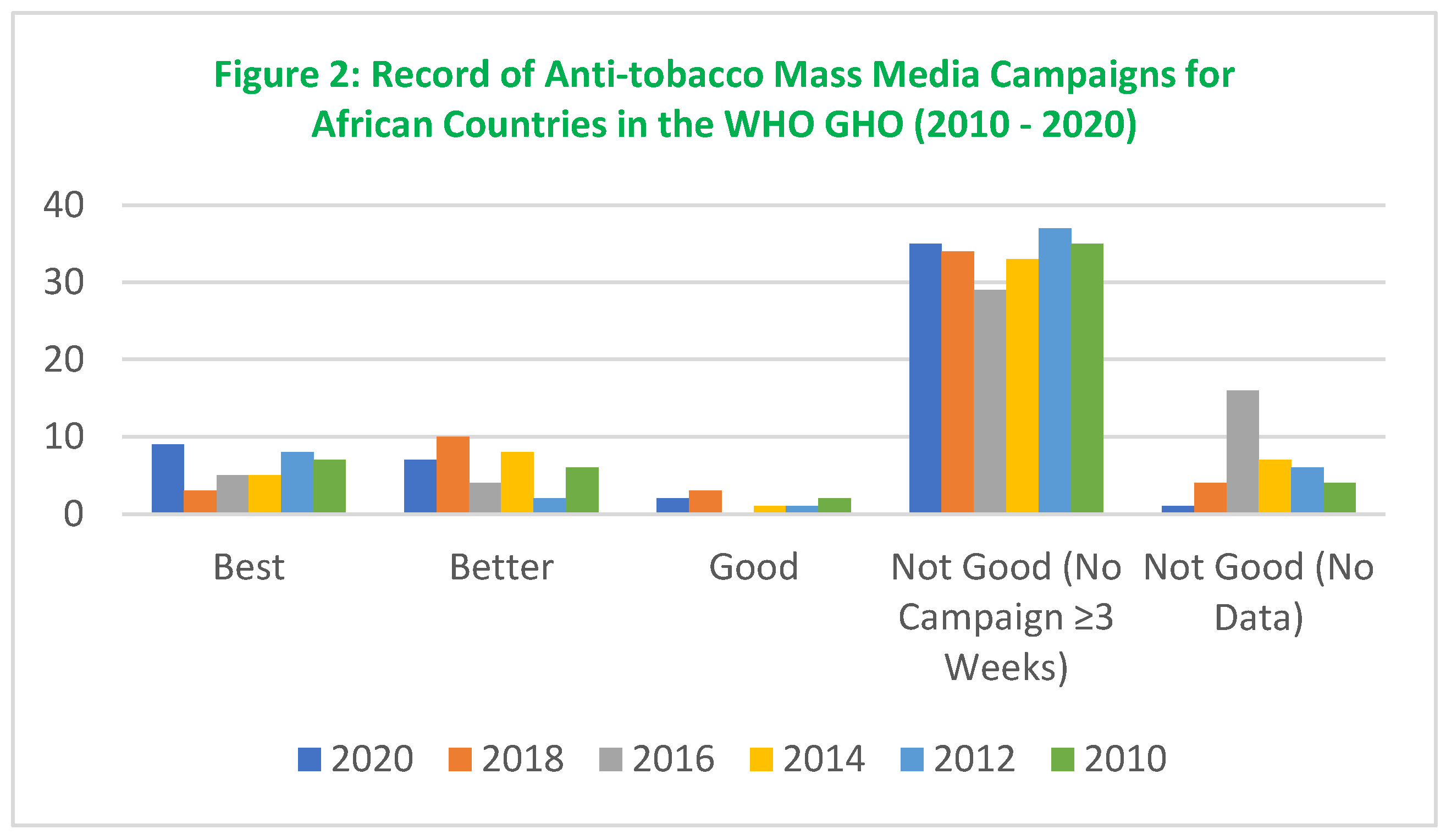

- WHO Global Health Observatory database: The data extraction items covered include; African country, World Bank Income group of African Country, Number of Campaigns Recorded (2010 – 2020), WHO ATMCs Category, Review Score and Overall Review Score. A summary of the extracted data is highlighted in Figure 2 while the full list for 54 countries is in appendix A.

- B.

- WHO FCTC Article 12 Reports: Number of Parties (Countries) that applied Article 12, Year of WHO FCTC Report, Average % Implementation Rate of Article 12, % of Parties Focused on Health Risk of Tobacco Consumption, % of Parties Targeting Children, Stakeholders Involved in implementation of programmes, and African country mentioned in Year of Report. A summary of the extracted data is highlighted in appendix B.

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.1.1. Peer Reviewed Sources

3.1.2. Grey Sources

| Number of African Countries | Total Number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Campaign Recorded |

Best (3) National Campaign with ≥7 CTS (Plus TV/Radio) |

Better (2) National Campaign with ≤7 CTS (No TV/Radio) |

Good (1) National Campaign with ≤4 CTS |

Not Good (0) No National Campaign ≥ 3 Weeks |

Not Good (0) No Data Reported |

|

| 2010 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 35 | 4 | 54 |

| 2012 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 37 | 6 | 54 |

| 2014 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 33 | 7 | 54 |

| 2016 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 29 | 16 | 54 |

| 2018 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 34 | 4 | 54 |

| 2020 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 35 | 1 | 54 |

| Average | 7 | 6 | 9 | 33 | 6 | |

| Author/Year | Setting | Area/Type Of Health Communication Addressed | Aim of Study | Study design/Method |

Population (Age/N Size) |

Involvement of Young People in Intervention Design |

| Perl et al., (2015) | Senegal, Nigeria and Kenya | Mass Media Campaigns Mass media 5 Radio and 5 TV antismoking advertisements |

Adapt available anti-tobacco television and radio advertisements from high-income countries for African countries | Mixed Methods Study | 1078 Male and Female adult smokers and Non smokers 18 – 40 years |

Not Involved in Design Other Tobacco control stakeholders involved in adaptation before study |

| Mansour et al., (2023) | Tunisia |

Media HWLs |

Improve and adapt a set of 16 pictorial Water pipe specific health warning labels (HWLs) created in an international Delphi study, to the Tunisian context |

Mixed Methods Study | 63 young adults 18-43 years | Not Involved in Design |

| Mostafa et al., (2018) | Egypt |

Media HWLs |

Investigate whether PHWs on Water pipe tobacco products lead to behavior change |

Quantitative Study | 2014 waterpipe smokers and non-smokers aged 18 years or older | Not Involved in Design |

| Oyapero et al., (2021) | Lagos, Nigeria | N/A Anti-tobacco Messages (ATM) |

Assess the association between exposure to Anti-Tobacco Messaging (ATM) and quit attempts among adolescents and young adults in Lagos, Nigeria |

Quantitative Study | 947 participants 15–35 years | N/A |

| Singh et al., (2014) | Kumasi, Ghana | Media Text and Pictorial Health Warnings |

Examine how Ghanaian smokers and nonsmokers view warning labels (text and pictures) on cigarette packs and to investigate their opinions regarding the implementation of pictorial warnings in Ghana | Qualitative Study | (85) 50 smokers and 35 nonsmokers aged 15 years and older | Not Involved in Design |

| Odukoya et al., (2020) | Nigeria | Professional Medical Communications Text Messaging |

Improve text messaging as an intervention among physicians to help them foster tobacco treatment (cessation) among their patients. Focal patients at least 12 years |

Quantitative Study | (N =946) Respondents =165) In 3 tertiary care hospitals Age of Medical personnel not mentioned |

N/A |

| Karletsos et al., (2021) | Ghana |

Mass Media & New Media, & Interpersonal communication Social Media & Mass media (Blogs, magazines), Group meetings & Events (SKY Girls Campaign) |

Investigate how well anti-smoking messages, delivered through both mass media and social media, can help change how adolescents in urban Ghana think about the dangers of smoking, in a more positive direction |

Quantitative Study | First wave (7054) 3775 adolescent girls and 3279 adolescent boys aged 13–16 years in urban areas of Accra. Second wave 5069 participants | Not Involved in Design Minimally Involved in implementation |

| Borzekowski & Cohen (2014) | Brazil, China, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Russia | Media Text/Image Health Warning Labels (HWLs) |

Investigate the awareness and understanding of health warning labels among 5 and 6 year old children in six countries |

Quantitative Survey | 2423 5 - 6 Year old |

Not Involved in Design |

| Achia (2015) | Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Liberia, Lesotho, Malawi, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe | Mass Media Campaigns Television, Radio, newspapers or magazines |

Study the relationship between self-reported tobacco use and frequency of mass media utilization in nine LMICs in Sub Saharan Africa |

Quantitative Cross sectional design using Secondary Data Analysis from DHS | 159,462 Women aged 15–49 years (n = 101,316) & Men aged 15–59 years (n = 58,146) |

N/A |

| Wakefield et al., (2015) | From 10 LMICs - Bangladesh, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Philippines, Russia, Turkey & Vietnam |

Mass Media Five television advertisements |

Examine the comprehension, acceptability, and how effective 5 television advertisements could be in conveying anti-smoking message and encouraging adults in low- and middle-income countries to quit smoking. |

Mixed method study | 2399 smokers aged 18 - 34 years | Not Involved in Design |

| Bekalu et al., (2022) | Ethiopia | Mass Media Television, radio, billboards, posters, newspapers, magazines, movies |

Examine if tobacco risk perceptions varied across socioeconomic and urban vs. rural population subgroups, and whether and how exposure to anti-smoking message was associated with disparities in risk perceptions across socioeconomic and urban-rural subgroups | Quantitative Cross sectional survey using secondary data analysis from GATS Ethiopia 2016 | 10,150 Male/Female 15 years and above |

N/A |

| Azagba et al., (2015) | Mauritius | Mass media Campaign (sponge) Television Advertisements |

Examine the combined effect of increase in cigarette excise tax and anti-tobacco mass media campaign (sponge) on smoking behaviour. | Quantitative – Longitudinal Study International Tobacco Control Mauritius Survey, 2009 – 2011 using Secondary longitudinal data analysis |

725 Respondents Adults Smokers and Non-Smokers (aged ≥18 years) |

N/A |

| Owusu et al., (2017) | 14 LMICs including Nigeria and Egypt (2009-2012) |

Mass Media Newspapers or magazines, television, radio, and billboards |

Evaluated factors associated with three stages of intention to quit tobacco smoking among adults in 14 LMICs by using the transtheoretical model (TTM) of health behavior change (precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation) | Quantitative Cross Sectional Secondary data analysis of Publicly available GATS data from 14 LMICs from 2009 to 2012 |

43,540 current tobacco smokers aged 15 years and above |

N/A |

| Adebiyi et al., (2016) | Igbo-Ora, Nigeria | Media Graphic Health Warnings |

To examine if the use of graphic health warnings can be effective in preventing smoking initiation among young people in Nigeria | Quantitative Cross-sectional study | (554) students aged 13–17years | Not Involved in Design |

| Hutchinson et al., (2020) | Ghana | Mass Media Magazine, movies, a radio program, social media and other promotional activities. |

Impact evaluation of SKY Girls, a youth-focused smoking-prevention and empowerment campaign targeting girls in Ghana | Quasi-experimental matched design | 2625 13-16 year old girls | N/A |

| Mostafa et al., (2021) | Egypt | Media Waterpipe Warning Labels (WTP WL) |

Measure the perceived efficacy of existing against novel enhanced (generic and waterpipe-specific) WTP WLs and the associated factors among Egyptian waterpipe smokers and nonsmokers. |

Quantitative Design | 2014 Male and female waterpipe smokers and nonsmokers ≥18 years | Not Involved in Design |

| Uchendu et al., (2018) | Nigeria | Constituency relations |

To examine retailer awareness of tobacco control laws and willingness to be involved in control activities. | Quantitative - Cross sectional | 218 participants >30 ≥50 years |

N/A |

| Khalbous & Bouslama (2012) | Tunis, Tunisia | Media Visual (Paper) Advertisements |

To understand the relationship between smoking socialization and the effectiveness of anti-tobacco advertisements | Quantitative – Panel Surveys | 351 students 12 -16 years |

Not Involved in Design |

| Siziya et al., (2008) | Somaliland | Mass Media Television, radio, billboards, posters, newspapers, magazines, movies |

To estimate the prevalence of cigarette smoking, and determine associations of antismoking messages with smoking status | Quantitative Cross sectional survey using secondary data analysis from GYTS Somaliland 2004 | 1563 students 13 – 15 years |

N/A |

| Odukoya et al., (2014) | Lagos, Nigeria | Mass Media Health talks, information leaflets and posters |

To assess the effect of a short school-based anti-smoking program on the knowledge, attitude and practice of cigarette smoking among students in secondary schools in Lagos State | Quantitative – Non-randomized, controlled intervention | 1031 students 10 – 21 years |

Not Involved in Design Information leaflets and posters designed & Introduced by researcher |

3.2. Participant Characteristics

3.3. Study Findings

3.3.1. Content and the Presentation Matters

3.3.2. Reaction to Anti-tobacco Content Varies

3.3.3. Anti-tobacco Messages can Influence Smoking

3.3.4. Message Clarity and Contextual Considerations

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Data Citation

Acknowledgments

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: WHO Global Health Observatory Anti-tobacco Mass Media Campaigns For 54 African Countries 2010 - 2020

| Country | World Bank Income Group | Number of Campaigns Recorded (2010 – 2020) |

Best (3) National Campaign with ≥7 CTS (Plus TV/Radio) |

Better (2) National Campaign with ≤7 CTS (No TV/Radio) |

Good (1) National Campaign with ≤4 CTS |

Not Good (0) No National Campaign ≥ 3 Weeks |

Not Good (0) No Data Reported |

Overall Review Score |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2020 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2018 (0) |

3 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2014 (2) 2012 (2) |

0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) | 4 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2020 (2) 2010 (2) |

2018 (1) | 2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

2012 (0) | 5 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2016 (3) 2014 (3) |

0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2018 (0) |

6 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2020 (3) | 2018 (2) | 0 | 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 5 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2014 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) 2012 (0) |

2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2018 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) | 2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2010 (0) |

2012 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 |

2020 (2) 2018 (2) 2016 (2) 2014 (2) |

2010 (1) | 2012 (0) | 0 | 9 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2012 (0) |

2010 (0) 2014 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2014 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) |

2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2012 (3) 2010 (3) |

0 | 2020 (1) | 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

0 | 7 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2018 (0) 2016 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2010 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

2016 (0) | 2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2020 (3) |

2018 (2) 2016 (2) |

2012 (1) | 2014 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 8 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

2010 (0) | 0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2020 (2) 2018 (2) 2014 (2) |

0 | 2016 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 6 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2020 (3) 2014 (3) 2012 (3) |

2018 (2) | 0 | 2016 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 9 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2010 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

0 | 2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2014 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2016 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 3 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2018 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) |

2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2012 (3) | 2020 (2) | 0 | 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) |

5 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2014 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 3 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2012 (3) 2010 (3) |

0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

0 | 6 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

2016 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2016 (3) 2012 (3) |

2014 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 8 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2020 (3) 2016 (3) 2010 (3) |

2018 (2) | 0 | 2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

0 | 11 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2020 (3) | 2018 (2) | 0 | 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 5 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2010 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

2012 (0) | 3 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2020 (3) 2010 (3) |

2012 (2) | 2018 (1) | 2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

0 | 9 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2012 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) 2014 (0) |

3 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2018 (3) 2014 (3) |

0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2016 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 6 |

|

High Income | 6 |

2018 (3) 2016 (3) 2012 (3) |

2020 (2) | 2010 (1) | 2014 (0) | 0 | 12 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2016 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2012 (0) |

2014 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2020 (2) | 0 | 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2010 (2) | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) |

2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

2 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2014 (2) 2010 (2) |

0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2012 (0) |

0 | 4 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2020 (3) 2018 (3) 2010 (3) |

2014 (2) | 0 | 2016 (0) 2012 (0) |

0 | 11 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 |

2020 (3) 2014 (3) 2012 (3) |

2016 (2) 2010 (2) |

2018 (1) | 0 | 0 | 14 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 2020 (2) 2018 (2) |

2014 (1) | 2016 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 5 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2014 (0) 2010 (0) |

2016 (0) 2012 (0) |

0 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 2010 (3) | 0 | 2020 (1) | 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) |

0 | 4 |

|

Low & Middle Income | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2020 (0) 2018 (0) 2016 (0) 2014 (0) 2012 (0) 2010 (0) |

0 | 0 |

Appendix B: Global Progress Report on the Implementation of the WHO FCTC 2010 – 2021 (Article 12: African Parties)

| Number of countries (parties) that reported implementing Article 12 | Year of WHO FCTC Report | Average % Implementation Rate of Article 12 | % of Parties Focused on Health Risk of Tobacco Consumption | % of Parties Targeting Children | Stakeholders Involved in implementation of Programmes | African Country Mentioned in Year of Report |

| 114 | 2010 | Not mentioned | 80 | Not given (4 out of 5) |

Public agencies and nongovernmental organizations not affiliated with the tobacco industry |

None |

| 115 | 2012 | 70 | 100 | 98 | Public agencies and nongovernmental organizations, private organizations, religious and faith-based organizations; academic and higher education institutions; community and scientific groups, and professional colleges; as well as international organizations and bodies (Page 34) |

Ghana Training of Healthcare Professionals by the Ministry of Health (Pg 33) Djibouti Unavailable resources for impactful campaigns (Pg 35) |

| 125 | 2014 | 70 | 100 | 99 | Public agencies and NGOs, private organizations, religious and faith-based organizations; academic, higher education institutions and hospitals; community and scientific groups, and professional colleges; municipalities; the media; and international organizations, including WHO. (Page 35) |

Senegal Launch of first ever anti-tobacco media campaign called “Sponge” (Pg 34) |

| 119 | 2016 | 90 | 100 | 99 | Public agencies, and non-governmental organizations involved in development and implementation of intersectoral programmes and strategies for tobacco control. Private organizations, academic, higher educational institutions; community and scientific groups; professional colleges; municipalities; the media; and international organizations, including WHO (Pg35/36) |

Seychelles launch or culmination of national programme planned to align with World No Tobacco Day (Pg 34) |

| 162 | 2018 | 99 | 99 | 99 | Public agencies, NGOs involved in the development and implementation of intersectoral programmes and strategies for tobacco control. Academic and higher education institutions; community and scientific groups; hospitals and research institutes; professional colleges; police and military; the media; and international organizations, including WHO. (Pg 40/41) |

Chad New Campaign on Oral cancer (Pg 37) Training young peer educators in smoking prevention (Pg 40) Nigeria Launched campaign called “#ClearTheAir” to support new smoke-free legislation (Pg 39) Malta Training of local administrators and police officers after smoking ban in cars when minors are present (Pg 40) Either established comprehensive national tobacco control communications strategy/action plan or in the process of developing one (Pg 41) |

| 166 | 2021 | 92 | 99 | 96 | Public agencies, NGOs, Academic and higher education institutions, community and scientific groups, professional colleges, police and the military, the media, and international organizations including WHO were involved in the development and implementation of intersectoral programmes and strategies for tobacco control (Pg 52) |

Senegal Continued or further developed previously established campaigns/activities (Pg 47) World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) Campaign (Pg 47) Mauritius Continued or further developed previously established campaigns/activities (Pg 47) |

| This table shows WHO FCTC parties between 2010 and 2021 with extracted items for Article 12. | ||||||

References

- World Health Organization - Tobacco. Available Online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (Accessed 17 October 2023).

- Blecher, E.; Ross, H. Tobacco Use in Africa: Tobacco Control through Prevention Tobacco Use in Africa. Am. Cancer Society 2013, 1-16. Available online: https://www.iccp-portal.org/system/files/resources/acspc-041294.pdf (Accessed March 2021).

- Bilano, V.; Gilmour, S.; Moffiet, T.; D’Espaignet, E. T.; Stevens, G. A.; Commar, A.; Tuyl, F.; Hudson, I.; Shibuya, K. Global Trends and Projections for Tobacco Use, 1990-2025: An Analysis of Smoking Indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. The Lancet 2015, 385 (9972), 966–976. [CrossRef]

- Méndez, D.; Alshanqeety, O.; Warner, K. E. The potential impact of smoking control policies on future global smoking trends. Tobacco Control 2013, 22, 46–51. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Atlas of African Health Statistics 2022- Health Situation Analysis of the African Region. Available Online https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-african-health-statistics-2022-health-situation-analysis-who-african-region-0 (Accessed 15 June 2023).

- United Nations Children’s Fund- Generation 2025 and Beyond: The Critical importance of understanding demographic trends for children of the 21st century. 2012 Available Online: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Generation_2025_and_beyond_Nov2012_42.pdf (Accessed 6 October 2022).

- Reitsma, B.; Kendrick, J.; Ababneh E., et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet 2021;397:2337–60. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization - Best buys and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: Tackling NCDs Best Buys. Available Online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232 (Accessed 10 June 2021).

- World Health Organization – The Global Tobacco Epidemic 2023 (p71). Available Online: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/tobacco-control/global-tobacco-report-2023 (Accessed August 15 2023).

- Society For Health Communication- About Health Communication. Available online: https://www.societyforhealthcommunication.org/health-communication (Accessed 10 September 2021).

- Renata Schiavo. Health Communication: From Theory to Practice, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand: San Francisco, United States, 2014; pp. 26-28.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices User Guide: Health Communications in Tobacco Prevention and Control. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/guides/pdfs/health-communications-508.pdf (Accessed 10 June 2021).

- Bell, J.; Condren, M. Communication Strategies for Empowering and Protecting Children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2016; Vol. 21, pp 176–184.

- Cavallo, D. A.; Kong, G.; Ells, D. M.; Camenga, D. R.; Morean, M. E.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. Youth Generated Prevention Messages about Electronic Cigarettes. Health Education Research 2019, 34 (2), 247–256. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M. W.; Wray, R. J. Tailored and Targeted Health Communication: Strategies for Enhancing Information Relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior 2003; Vol. 27. [CrossRef]

- Durkin, S.; Bayly, M.; Cotter, T.; Mullin, S.; Wakefield, M. Potential Effectiveness of Anti-Smoking Advertisement Types in Ten Low and Middle Income Countries: Do Demographics, Smoking Characteristics and Cultural Differences Matter? Social Science and Medicine 2013, 98, 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Malone, R. E.; Grundy, Q.; Bero, L. A. Tobacco Industry Denormalisation as a Tobacco Control Intervention: A Review. Tobacco Control 2012, 21 (2), 162–170. [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, M. C.; Davis, K. C.; Duke, J.; Messeri, P. Sustaining “Truth”: Changes in Youth Tobacco Attitudes and Smoking Intentions after 3 Years of a National Antismoking Campaign. Health Education Research 2009, 24 (1), 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, M. C.; Davis, K. C.; Lyndon Haviland, M.; Messeri, P.; Healton, C. G. Evidence of a Dose-Response Relationship Between “Truth” Antismoking Ads and Youth Smoking Prevalence. 2005, 95 (3). [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, P.; Leyton, A.; Meekers, D.; Stoecker, C.; Wood, F.; Murray, J.; Dodoo, N. D.; Biney, A. Evaluation of a Multimedia Youth Anti-Smoking and Girls’ Empowerment Campaign: SKY Girls Ghana. BMC Public Health 2020, 20 (1). [CrossRef]

- Karletsos, D.; Hutchinson, P.; Leyton, A.; Meekers, D. The Effect of Interpersonal Communication in Tobacco Control Campaigns: A Longitudinal Mediation Analysis of a Ghanaian Adolescent Population. Preventive Medicine 2021, 142. [CrossRef]

- Egbe, C. O.; Magati, P.; Wanyonyi, E.; Sessou, L.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Ayo-Yusuf, O. A. Landscape of Tobacco Control in Sub-Saharan Africa. Tobacco Control 2022, 31 (2), 153–159. [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, P. A.; Cadman, B.; Malone, R. E. African Media Coverage of Tobacco Industry Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives. Global Public Health 2018, 13 (2), 129–143. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization- Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (Accessed August 15 2023).

- Anderson, C. L.; Becher, H.; Winkler, V. Tobacco Control Progress in Low and Middle Income Countries in Comparison to High Income Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13 (10). [CrossRef]

- Wisdom, J.P., Juma, P., Mwagomba, B. et al. Influence of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control on tobacco legislation and policies in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A. B.; Fooks, G.; Drope, J.; Bialous, S. A.; Jackson, R. R. Exposing and Addressing Tobacco Industry Conduct in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. The Lancet 2015, 385 (9972), 1029–1043. [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, B. K.; Animasahun, V. J.; Chapman, H. J. Tobacco Use in Nigerian Youth: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13 (5). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: Targets of Sustainable Development Goal 3. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/sustainable-development-goals/targets-of-sustainable-development-goal-3 (Accessed November 13, 2023).

- PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) Checklist. Available online: Appendix 11.2 PRISMA ScR Extension Fillable Checklist - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki (refined.site) (Accessed July 15, 2023).

- World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control – Article 12 Technical Document. Available online: https://fctc.who.int/docs/librariesprovider12/technical-documents/who-fctc-article-12.pdf?sfvrsn=9249246b_57&download=true#:~:text=Article%2012%20of%20the%20Convention,the%20guidelines%20on%20Article%2014 (Accessed January 2021).

- World Health Organization Global Health Observatory. Available Online: https://www.who.int/data/gho (Accessed 16 June 2023).

- World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Reports. Available Online: https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/reporting/global-progress-reports (Accessed January 2022).

- World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Reporting Instrument. Available Online: https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/reporting/reporting-instrument (Accessed January 2022).

- JBI Manual For Evidence Synthesis. Available Online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687579/Appendix+11.1+JBI+template+source+of+evidence+details%2C+characteristics+and+results+extraction+instrument (Accessed July 15, 2023).

- Perl, R.; Murukutla, N.; Occleston, J.; Bayly, M.; Lien, M.; Wakefield, M.; Mullin, S. Responses to Antismoking Radio and Television Advertisements among Adult Smokers and Non-Smokers across Africa: Message-Testing Results from Senegal, Nigeria and Kenya. Tobacco Control 2015, 24 (6), 601–608. [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.; Bayly, M.; Durkin, S.; Cotter, T.; Mullin, S.; Warne, C. Smokers’ Responses to Television Advertisements about the Serious Harms of Tobacco Use: Pre-Testing Results from 10 Low- to Middle-Income Countries. Tobacco Control 2013, 22 (1), 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Achia, T. N. O. Tobacco Use and Mass Media Utilization in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10 (2). [CrossRef]

- Azagba, S.; Burhoo, P.; Chaloupka, F. J.; Fong, G. T. Effect of Cigarette Tax Increase in Combination with Mass Media Campaign on Smoking Behaviour in Mauritius: Findings from the ITC Mauritius Survey. Tobacco Control 2015, 24, iii71–iii75. [CrossRef]

- Bekalu, M. A.; Gundersen, D. A.; Viswanath, K. Beyond Educating the Masses: The Role of Public Health Communication in Addressing Socioeconomic- and Residence-Based Disparities in Tobacco Risk Perception. Health Communication 2022, 37 (2), 214–221. [CrossRef]

- Owusu, D.; Quinn, M.; Wang, K. S.; Aibangbee, J.; Mamudu, H. M. Intentions to Quit Tobacco Smoking in 14 Low- and Middle-Income Countries Based on the Transtheoretical Model*. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2017, 178, 425–429. [CrossRef]

- Siziya, S., Rudatsikira, E., & Muula, A. S. Antismoking messages and current cigarette smoking status in Somaliland: results from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey 2004. Conflict and Health 2008, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Oyapero, A.; Erinoso, O. A.; Osoba, M. E. Exposure to Anti-Tobacco Messaging and Quit Attempts among Adolescent and Young Adult in Lagos, Nigeria: A Population-based Study. The West African Medical Journal 2021, 38(11):1058-1064.

- Khalbous, S., & Bouslama, H. Tobacco Socialization and Anti-Tobacco Ad Effectiveness Among Children. Health Marketing Quarterly 2012, 29(2), 97–116. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, N. B.; Rejaibi, S.; Mahfoudh, A. S.; Youssef, S. B.; Romdhane, H. B.; Schmidt, M.; Ward, K. D.; Maziak, W.; Asfar, T. Adapting Waterpipe-Specific Pictorial Health Warning Labels to the Tunisian Context Using a Mixed Method Approach. PLoS ONE 2023, 18 (3 March). [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, A. O.; Uchendu, O. C.; Bamgboye, E.; Ibitoye, O.; Omotola, B. Perceived Effectiveness of Graphic Health Warnings as a Deterrent for Smoking Initiation among Adolescents in Selected Schools in Southwest Nigeria. Tobacco Induced Diseases 2016, 14 (1). [CrossRef]

- Borzekowski, D. L. G.; Cohen, J. E. Young Children’s Perceptions of Health Warning Labels on Cigarette Packages: A Study in Six Countries. Journal of Public Health (Germany) 2014, 22 (2), 175–185. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.; Mohammed, H. T.; Hussein, R. S.; Hussein, W. M.; Elhabiby, M.; Safwat, W.; Labib, S.; Fotouh, A. A. Do Pictorial Health Warnings on Waterpipe Tobacco Packs Matter? Recall Effectiveness among Egyptian Waterpipe Smokers & Nonsmokers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13 (12). [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A; El Houssinie, M; Hussein, R.S. Perceived efficacy of existing waterpipe tobacco warning labels versus novel enhanced generic and waterpipe-specific sets. PLoS ONE 2021, 16(7): e0255244. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Britton, J.; Munafò, M. R.; Jones, L. L. “Pictures Don’t Lie, Seeing Is Believing”: Exploring Attitudes to the Introduction of Pictorial Warnings on Cigarette Packs in Ghana. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 2014, 16 (12), 1613–1619. [CrossRef]

- Odukoya, O.; Faseru, B.; Uguru, N.; Jamda, M.; Onigbogi, O.; James, O.; Leischow, S.; Ayo-Yusuf, O. Text Messaging Promoting Physician-Led Brief Intervention Tobacco Cessation: A before-and-after Study among Physicians in Three Tertiary Hospitals in Nigeria. Substance Abuse 2020, 41 (2), 186–190. [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, O.; Adebiyi, A. O.; Adeyera, O. Willingness of Tobacco Retailers in Oyo State to Participate in Tobacco Control Programmes. Tobacco Prevention and Cessation 2018, 4 (January). [CrossRef]

- Odukoya, O. O., Odeyemi K.A., Oyeyemi A. S., Upadhyay R. P. ‘The effect of a short anti-smoking awareness programme on the knowledge, attitude and practice of cigarette smoking among secondary school students in Lagos state, Nigeria.’ The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal 2014, 21(2), pp. 128–135.

- Asfar, T., Schmidt, M., Ebrahimi Kalan, M., Wu, W., Ward, K. D., Nakkash, R. T., Thrasher, J., Eissenberg, T., Ben Romdhane, H., & Maziak, W. Delphi study among international expert panel to develop waterpipe-specific health warning labels. Tobacco Control 2020, tobaccocontrol-2018-054718. [CrossRef]

- Mamudu, H. M.; Subedi, P.; Alamin, A. E.; Veeranki, S. P.; Owusu, D.; Poole, A.; Mbulo, L.; Ogwell Ouma, A. E.; Oke, A. The Progress of Tobacco Control Research in Sub-Saharan Africa in the Past 50 Years: A Systematic Review of the Design and Methods of the Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15 (12). [CrossRef]

- Doku, D., Koivusilta, L., Raisamo, S., & Rimpelä, A. Tobacco use and exposure to tobacco promoting and restraining factors among adolescents in a developing country. Public Health 2012, 126(8), 668–674. [CrossRef]

- Egbe, C. O.; Petersen, I.; Meyer-Weitz, A.; Asante, K. O. An Exploratory Study of the Socio-Cultural Risk Influences for Cigarette Smoking among Southern Nigerian Youth. BMC Public Health 2014, 14 (1). [CrossRef]

- Kirk, A. How Influences on Teenage Smoking Reflect Gender and Society in Mali, West Africa. JRSM Short Reports 2012, 3 (1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: protect people from tobacco smoke. Available online https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077164 (Accessed October 5, 2023).

- African Tobacco Control Alliance. African Tobacco Industry Interference Index 20223. Available online: https://atca-africa.org/africa-tobacco-industry-interference-index/ (Accessed November 5, 2023).

- Munthali, G. N. C., Wu, X.-L., Rizwan, M., Daru, G. R., & Shi, Y. Assessment of Tobacco Control Policy Instruments, Status and Effectiveness in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2021, 14:2913–2927. [CrossRef]

- Noar, S. M. A 10-Year Retrospective of Research in Health Mass Media Campaigns: Where Do We Go from Here? Journal of Health Communication 2006, 11 (1), 21–42. [CrossRef]

- Borzekowski, D. L. G.; Cohen, J. E. International Reach of Tobacco Marketing among Young Children. Pediatrics 2013, 132 (4). [CrossRef]

- Reggev, N.; Sharoni, R.; Maril, A. Distinctiveness Benefits Novelty (and Not Familiarity), but Only Up to a Limit: The Prior Knowledge Perspective. Cognitive Science 2018, 42 (1), 103–128. [CrossRef]

- Udokanma, E. E., Ogamba, I., & Ilo, C. A health policy analysis of the implementation of the National Tobacco Control Act in Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning 2021, 36(4), 484–492. [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance for Tobacco Control Strategic Plan 2022-2025. Available online https://fctc.org/resource-hub/gatc-strategic-plan-2022-2025/ (Accessed October 17, 2022).

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Demographic Dividend Atlas for Africa: Tracking the potential for a demographic dividend 2017. Available online https://www.unfpa.org/resources/demographic-dividend-atlas-africa-tracking-potential-demographic-dividend#:~:text=About%2060%20per%20cent%20of,United%20Nations%202017%20World%20Population (Accessed October 17, 2023).

- James, P. B., Bah, A. J., Kabba, J. A., Kassim, S. A., & Dalinjong, P. A. Prevalence and correlates of current tobacco use and non-user susceptibility to using tobacco products among school-going adolescents in 22 African countries: a secondary analysis of the 2013-2018 global youth tobacco surveys. Archives of Public Health, 2022, 80(1). [CrossRef]

- Hamill, S., Turk, T., Murukutla, N., Ghamrawy, M., & Mullin, S. I ‘like’ MPOWER: using Facebook, online ads and new media to mobilise tobacco control communities in low-income and middle-income countries. Tobacco Control 2013, 24(3), 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Mbulo, L.; Ogbonna, N.; Olarewaju, I.; Musa, E.; Salandy, S.; Ramanandraibe, N.; Palipudi, K. Preventing Tobacco Epidemic in LMICs with Low Tobacco Use — Using Nigeria GATS to Review WHO MPOWER Tobacco Indicators and Prevention Strategies. Preventive Medicine 2016, 91, S9–S15. [CrossRef]

- Ling, P. M.; Kim, M.; Egbe, C. O.; Patanavanich, R.; Pinho, M.; Hendlin, Y. Moving targets: how the rapidly changing tobacco and nicotine landscape creates advertising and promotion policy challenges. Tobacco Control 2022, 31:222–228. [CrossRef]

| WHO GHO Category |

| 5 = National Campaign with ≥7 CTS (Plus TV/Radio) |

| 4 = National Campaign with ≤7 CTS (No TV/Radio) |

| 3 = National Campaign with ≤4 CTS |

| 2 = No National Campaign ≥ 3 Weeks |

| 1 = No Data Reported |

|

CTS = Characteristics The characteristics (CTS) of a high-quality campaign as enumerated by the WHO include:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).