1. Introduction

Critical thinking, based on our research and project, is a pedagogical approach that has gained popularity worldwide in the past decades. However, its application in education has not been without its problems and challenges [

1,

2,

3].

Active methodology and critical pedagogy stand out in contemporary education for their focus on practical experience and the construction of knowledge relevant to the social reality and everyday life of students [

4]. Reis and Formosinho highlight their benefits for creativity, active participation, and knowledge retention through techniques such as project-based learning and the flipped classroom [

5]. On the other hand, critical pedagogy focuses on challenging educational inequalities and promoting social justice, recognizing the importance of an education that fosters critical awareness and transformative action [

6,

7]. Both approaches share the premise of placing the student at the center of learning, promoting knowledge connected to their environment, and participative strategies for the exchange of ideas [

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, critical pedagogy is distinguished by its commitment to addressing social inequalities and promoting social justice, while active methodology focuses more on the learning process and student participation [

12,

13,

14,

15].

The integration of active methodology within critical pedagogy is suggested as a means to foster active participation and critical reflection on social reality [

16,

17,

18]. Freire and other educators underline the importance of a didactic approach that promotes questioning and critical reflection through dialogue and the analysis of social issues [

19,

20]. According to Shor, critical pedagogy seeks to transform power structures within and outside the classroom, emphasizing that education must be contextualized to face the specific realities and challenges of each environment, especially in urban and multicultural contexts [

21,

22,

23,

24]. This critical approach is presented as essential for developing creative and sustainable solutions to social challenges, promoting an education that transcends the limitations imposed by external policies and regulations [

24].

Approaching the more specific premises that have inspired our project, it is important to bring in the contributions of Jean-François Lyotard to postmodernism, fundamentally his emphasis on language games as essential forms of communication and expression in society [

25]. Lyotard proposes that, in the postmodern era, knowledge has become decentralized, freed from the control of a central authority, implying a significant reconfiguration in the pedagogical realm [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. This decentralization suggests that students should be seen not as mere passive recipients of information but as active participants in the generation and production of knowledge, contributing their unique perspectives and experiences to the learning process [

30].

This approach goes beyond the traditional active method, proposing that knowledge is not a fixed entity owned by educators or experts, but a diverse and socially constructed spectrum [

31]. Student participation, in this framework, is not limited to activity in learning but encompasses an active role in the construction of knowledge, recognizing the importance of “tacit knowledge” and “personal knowledge,” acquired through experience and practice rather than objective observation, thus challenging traditional positivist perspectives [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Moreover, Lyotard and Polanyi highlight how factors such as linguistic and cultural affinities influence the acquisition of scientific knowledge, underlining the importance of considering multiculturalism within cities and, therefore, in the classroom [

37]. This approach proposes a paradigm shift towards a pedagogy that values and encourages diversity and inclusion, recognizing students as co-creators of knowledge within a broader and more diverse educational context.

Our educational project is also inspired by the theories of Henri Lefebvre, who emphasized collective and transformative action in education and other areas to modify social and political structures [

38]. Lefebvre critically examines urbanization, applying semiotic, structuralist, and poststructuralist methodologies to analyze urban complexity, promoting a deep understanding of urban space [

39,

40]. He opposes modernist views, emphasizing lived experience and the creation of an urban utopia based on self-determination and authenticity of social relationships, arguing that space is both a product and a medium of power relations [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

Lefebvre considers education essential in shaping spatial and social relationships, capable of reproducing or transforming dominant spaces and powers [

45,

49]. He highlights the need for spatial awareness to challenge power structures, positioning education as a vehicle for social transformation towards more inclusive and democratic spaces [

40]. He also analyzes how everyday aspects, affected by commodification and a lack of authenticity, can be sources of resistance and change, underlining the importance of reconsidering the everyday in post-consumerism [

50].

Similarly, our educational approach is based on the principles of Carl Rogers, who highlighted the potential for personal growth and self-realization, promoting a learning environment characterized by empathy, congruence, and active listening. This approach encourages active student participation in their learning process, considering them unique and autonomous beings [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Rogers, a pioneer of humanistic psychology, sees education as a means for personal development and the construction of meaningful knowledge through self-directed learning. His methodology aligns with critical pedagogy, emphasizing critical reflection and social transformation in education [

56,

57,

58].

Carvalho [

59] considers education a means for humanization, emphasizing its role in developing critical, autonomous individuals responsible for their actions. Formosinho et al. [

60] argues that education fosters freedom and personal responsibility, preparing individuals to be autonomous, socially responsible, and capable of managing their impulses through socialization and self-control.

Reflecting on post-truth in the context of critical pedagogy, we will highlight its impact on education, marked by an era where emotions and personal beliefs predominate over objective facts, complicating the educational field with the spread of fake news and information manipulation [

61,

62]. Frankfurt distinguishes deliberate deception from foolishness, with the latter being an indifference towards truth more harmful to the valuation of truthfulness [

63,

64]. Post-truth challenges the development of critical skills and evidence-based decision-making, encouraging reliance on unreliable sources [

65,

66,

67].

Neil Postman warned about the risks of an educational environment dominated by media entertainment, limiting the depth of learning [

68,

69]. He suggests focusing on critical thinking and media literacy to counter these effects, with Bandura emphasizing the importance of appropriate models for social learning in post-truth environments [

70,

71]. Giroux investigates how media culture and commercialization affect education, promoting a critical education that resists manipulation and misinformation [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76].

Not forgetting that our project carries a significant symbolic load, it is important to highlight Clifford Geertz’s concept of “symbolic efficacy,” referring to the power of cultural symbols in human perception and action, highlighting the influence of symbols in the construction of meaning and their relevance in education [

77,

78,

79,

80]. In this sense, we focus on edusemiotics, a pedagogical approach centered on meaning and communication that examines how signs and symbolic systems affect knowledge and learning, emphasizing the use of visual resources, interactive practices, and technologies to facilitate the construction of meanings [

81,

82,

83,

84]. This approach includes the analysis of signs in the educational environment, consideration of the cultural and social context in education, and the promotion of meaning construction by students [

85,

86,

87].

But Ford, advancing the ideas of Henri Lefebvre, believes that we can go beyond critical pedagogy to address these issues, exploring the connection between education and spatial production, and proposing a distinct political pedagogy [

46,

63]. Ford criticizes the individualistic tendency of critical pedagogy, promoting the integration of education and critical geography to analyze and transform spatial and power structures in education [

63,

67]. This pedagogy seeks to reform social and spatial structures influenced by capitalism, considering education as a transformative force [

65,

66,

88,

89,

90].

And to carry out all this, counter-mapping seems to us a very positive means. Mapping plays an important role in many fields and disciplines and is used, among other things, for planning and supporting decision-making in a wide variety of contexts [

91]. Insofar as critical geographers point out that cartography is always a political process situated in a social context with specific purposes and effects [

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96], we will use counter-mapping for this. Indeed, in recent years there have been publications that have explored fundamental changes in the way cartography is understood and practiced as a social process [

97]. Several authors have contributed to this discussion [

92,

95,

98].

To conceptualize the use of counter-mapping, we have been guided by the postulates of Nelson & Chen [

99] who present a problem-posing model based on Freire’s methodology [

13], structured in five phases to enrich teaching through critical approaches. This process begins with the exploration of relevant themes through critical dialogue, followed by the coding and decoding of these themes into symbolic representations. Subsequently, a reflective dialogue on the themes and their relationship with the students’ experiences is promoted, leading to transformative actions in their context and concluding with a critical evaluation of the entire process. This model encourages active participation, critical reflection, and informed decision-making, seeking not only learning but also the development of social awareness among students.

1.1. Objectives

1.1.1. General Objectives

Assess the impact of the counter-mapping project on university students’ knowledge and perception of their cities, focusing on urban dynamics, cultural diversity, and social challenges.

Examine how counter-mapping, as a pedagogical tool, can enrich understanding of urban spaces and foster active and committed citizenship among students.

Demonstrate the effectiveness of counter-mapping in developing critical skills, such as analytical thinking, active research, and effective communication, which are fundamental in the current urban and globalized context.

Explore the possibilities of counter-mapping to overcome the limitations of traditional teaching methods, promoting multidimensional learning that integrates active participation, on-site exploration, and critical reflection.

Contribute to the improvement of teaching related to urban life, community engagement, and social responsibility, through the implementation and evaluation of the counter-mapping project.

1.1.2. Specific Objectives

Measure the change in the level of knowledge and perception about urban geography, cultural history, social diversity, and urban challenges of students before and after participation in the counter-mapping project.

Analyze the transformation in the appreciation and understanding of the “invisible city” by students, highlighting the importance of personal and community narratives in the construction of urban identity.

Evaluate the effect of counter-mapping in promoting critical reflection on urban spaces and in fostering a substantial change in the perception and appreciation of the cultural and social diversity of their cities.

Identify how the counter-mapping methodology influences the development of critical thinking and creativity skills, essential for informed and active citizen participation.

Investigate the relationship between students’ prior knowledge of their cities and the learnings acquired during the project, to determine the accessibility and universality of counter-mapping as an educational tool.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

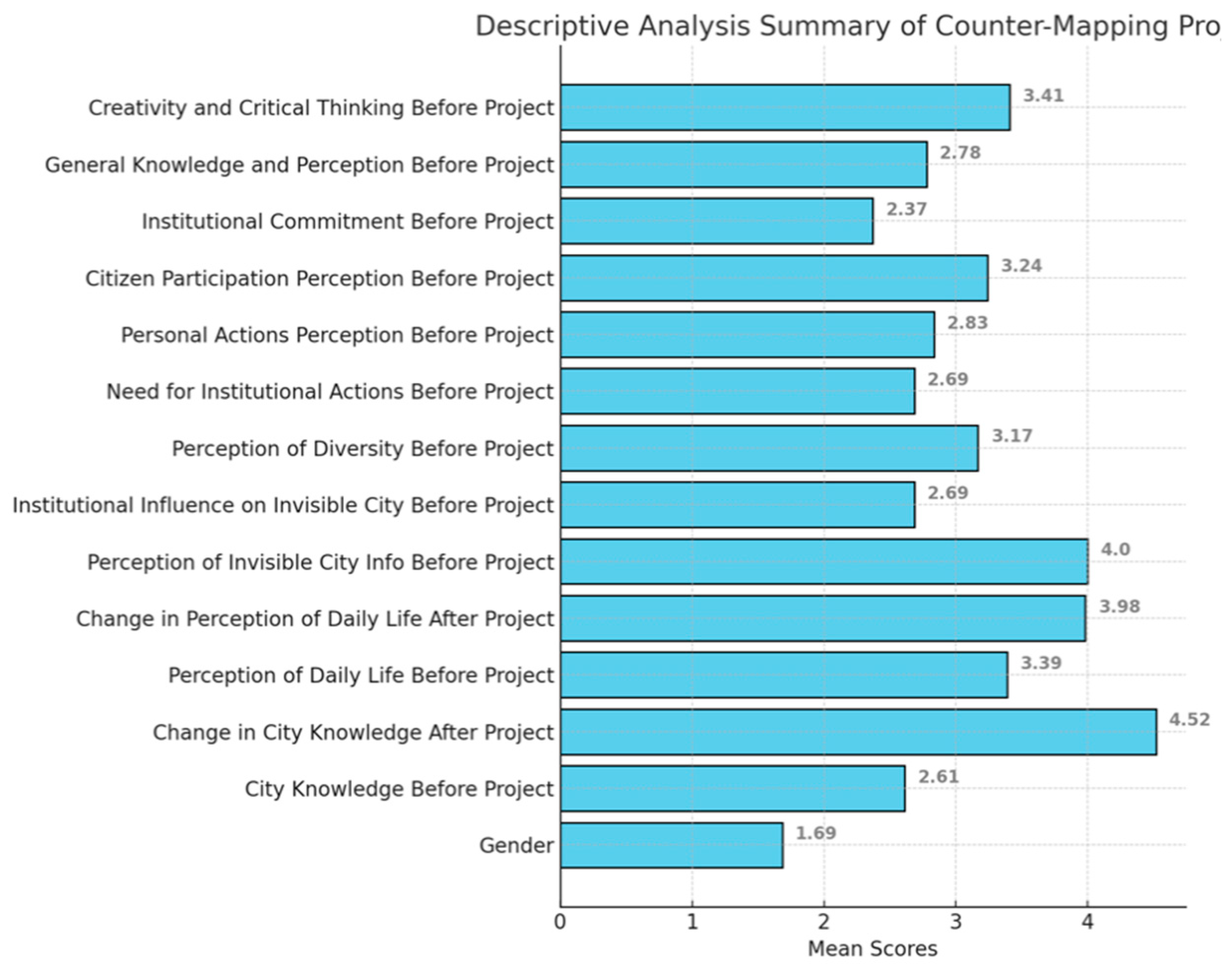

In the descriptive analysis of variables related to the counter-mapping project, aspects such as the number of responses, range, minimum and maximum values, total sum, and average were evaluated to understand the distribution and central tendencies of the participants’ responses.

The research showed that knowledge about the city before the project was average suggesting a moderate understanding by the participants. This knowledge experienced a significant increase after the project, as reflected by the average changes in knowledge and the post-project knowledge level (

Figure 2).

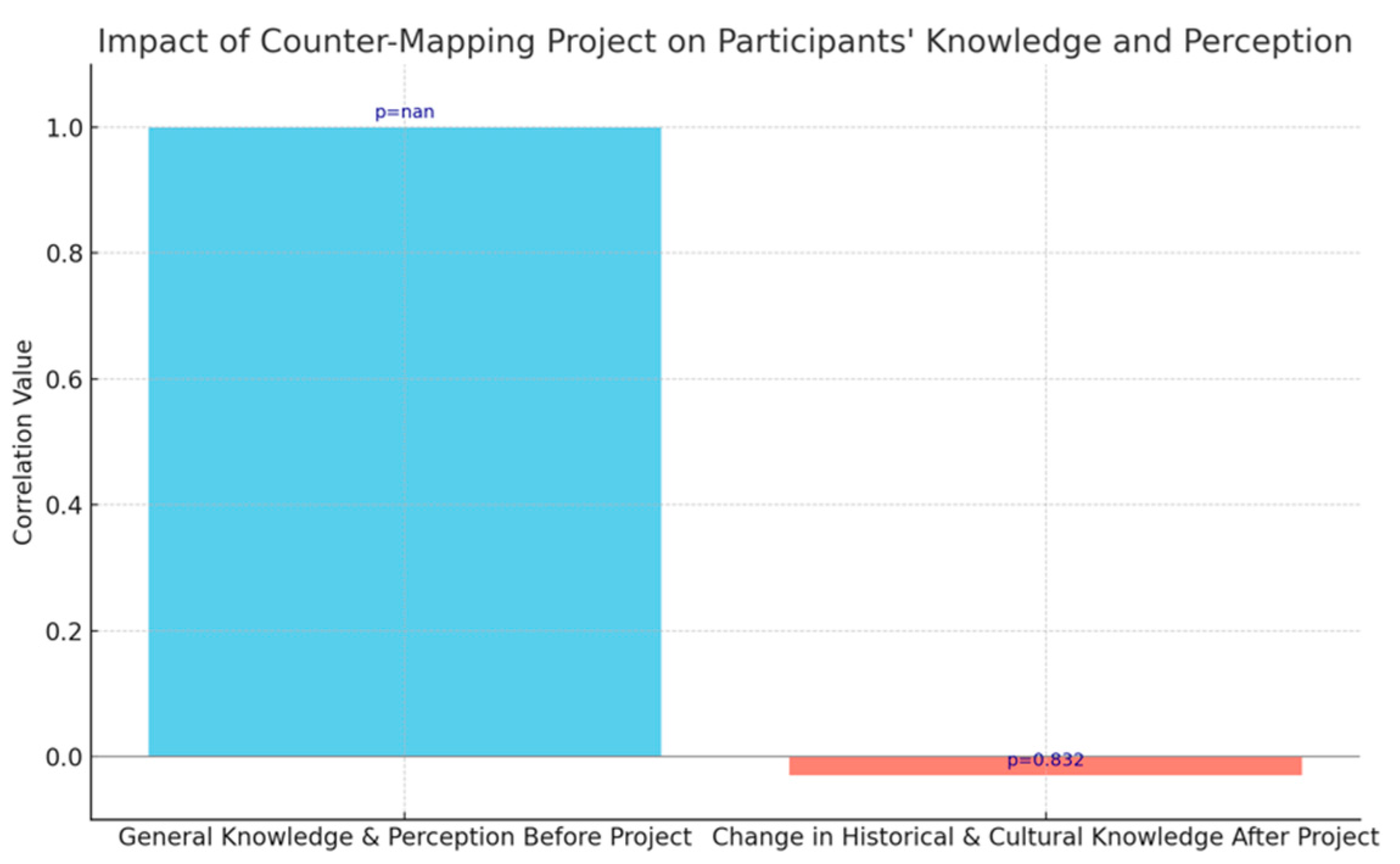

The data obtained from the counter-mapping project demonstrate a significant positive effect on the participants, evidenced by the increase in averages of almost all evaluated variables after participating in the project. This effect is observed in areas such as general knowledge and perception of the city, and creativity and critical thinking, indicating that the project has been crucial in enriching the participants’ awareness and understanding of their urban and cultural environment.

The data reflect variations in standard deviations, indicating different degrees of uniformity in the participants’ responses. Variations in standard deviation, both in decreases and increases, suggest that, while some aspects promoted greater alignment in perceptions, others observed a diversity of opinions and experiences that enriched the analysis of the project’s impact.

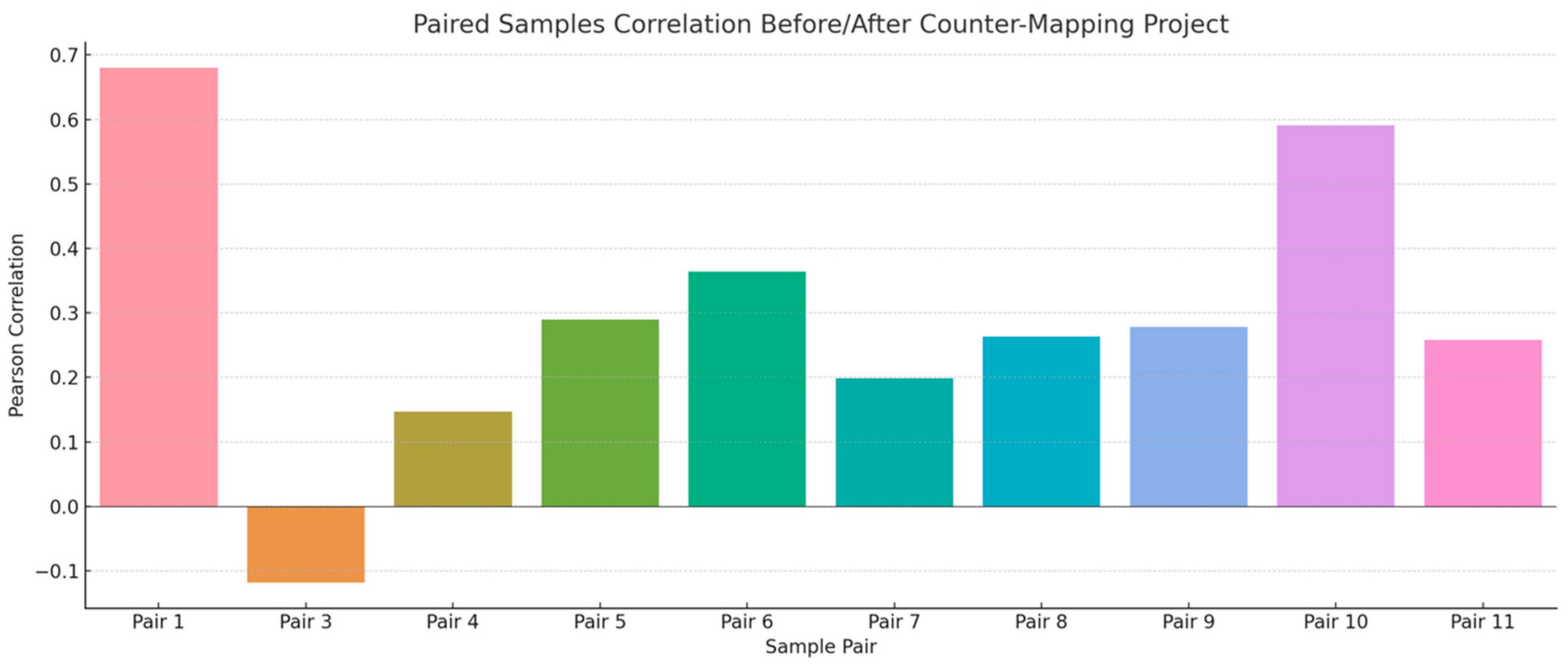

3.2. T-Test before and after Counter-Mapping

The application of the T-test for paired samples in the context of the counter-mapping project revealed significant changes in the participants’ perceptions and knowledge before and after their involvement in the project (

Figure 3). These changes reflect the project’s influence on different dimensions of the participants’ understanding and urban perception.

Significant increases in the level of knowledge about the city after the project (Pair 1) were identified, evidencing the project’s effectiveness in enriching the urban and heritage knowledge of the participants. Additionally, notable changes were recorded in the perception of everyday life and in how information about the “invisible” city is understood (Pair 3), indicating an increase in critical awareness of how information about the urban environment is presented and hidden.

The perception of cultural diversity also experienced a significant improvement (Pair 4), underlining the importance of recognizing the complexity and cultural richness of cities. From a transformative action perspective, both at the institutional (Pair 5) and personal levels (Pair 6), the project promoted recognition of the need to engage in change initiatives, highlighting the relevance of institutional and personal participation and commitment to urban transformation. This recognition extended to the perception of the importance of citizen participation (Pair 7), reinforcing the idea that citizen involvement is fundamental for the development of sustainable and participatory cities.

The results also indicate a positive impact of the project on personal commitment towards urban change (Pair 8), emphasizing the crucial role individuals play in the sustainable transformation of cities (Pair 9).

Thus, an overall increase in knowledge about the city (Pair 10) was observed, demonstrating the project’s capacity to expand participants’ urban understanding. Finally, the project had a favorable effect on promoting creativity and critical thinking (Pair 11), indispensable skills for addressing and solving contemporary urban challenges.

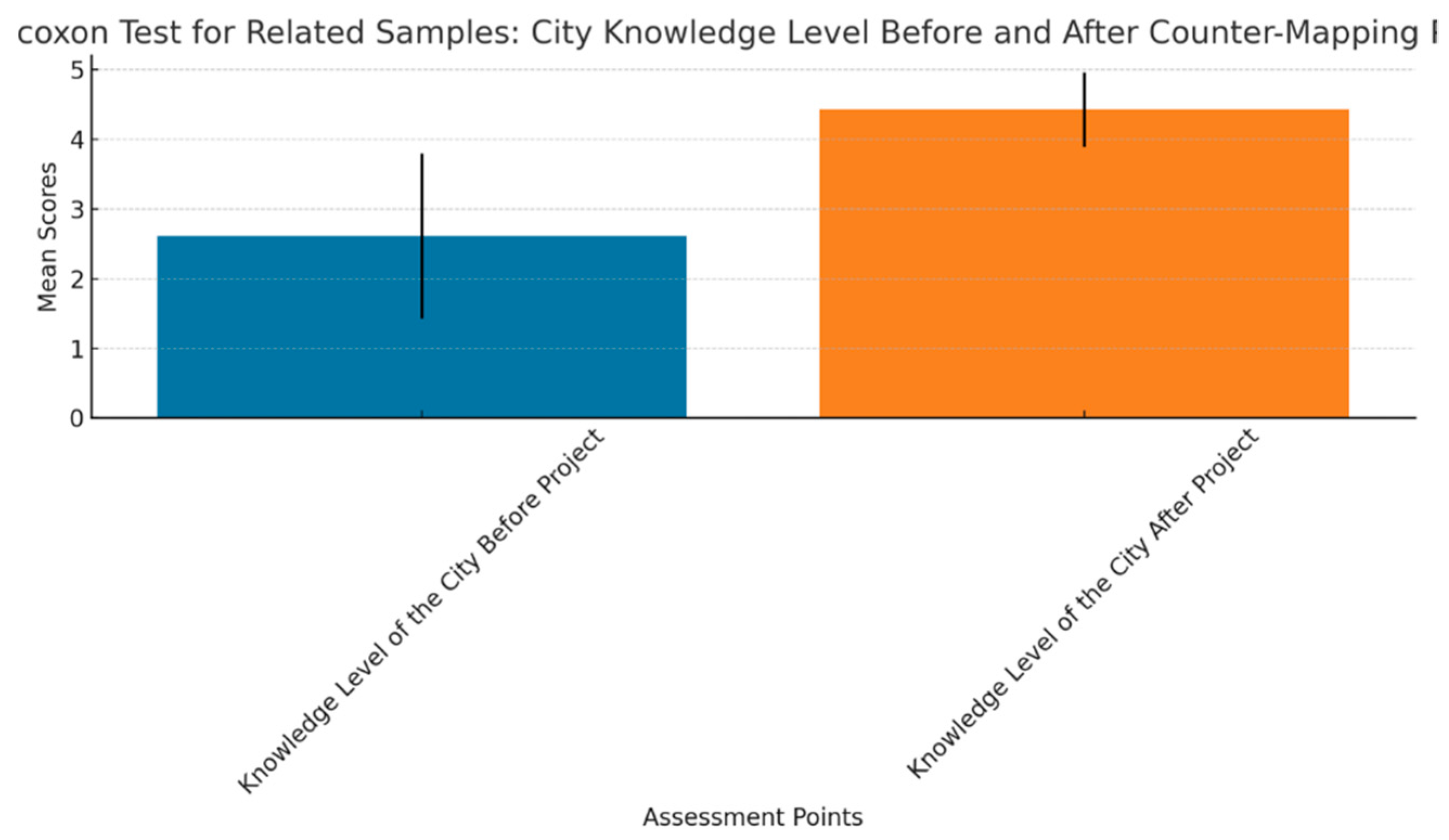

3.3. City Knowledge Level Before and After Wilcoxon Test for Related Samples

The Wilcoxon test, suitable for situations where differences between samples do not necessarily follow a normal distribution, provides a means to evaluate whether these changes are statistically significant without assuming the normality of distributions. Therefore, the application of the Wilcoxon test for related samples to analyze the level of knowledge about the city before and after the counter-mapping project offers a quantitative perspective on the educational impact of the initiative (

Figure 4).

With an initial mean of 2.6111 and a standard deviation of 1.18825 before the project, and a subsequent mean of 4.4259 with a standard deviation of 0.53560, the comparison of these data suggests a substantial improvement in the urban knowledge of the participants. The test result, with a W value of 0.0 and an approximate p-value of 2.00e-13, confirms that the difference in the level of knowledge about the city before and after the project is statistically significant at a conventional confidence level.

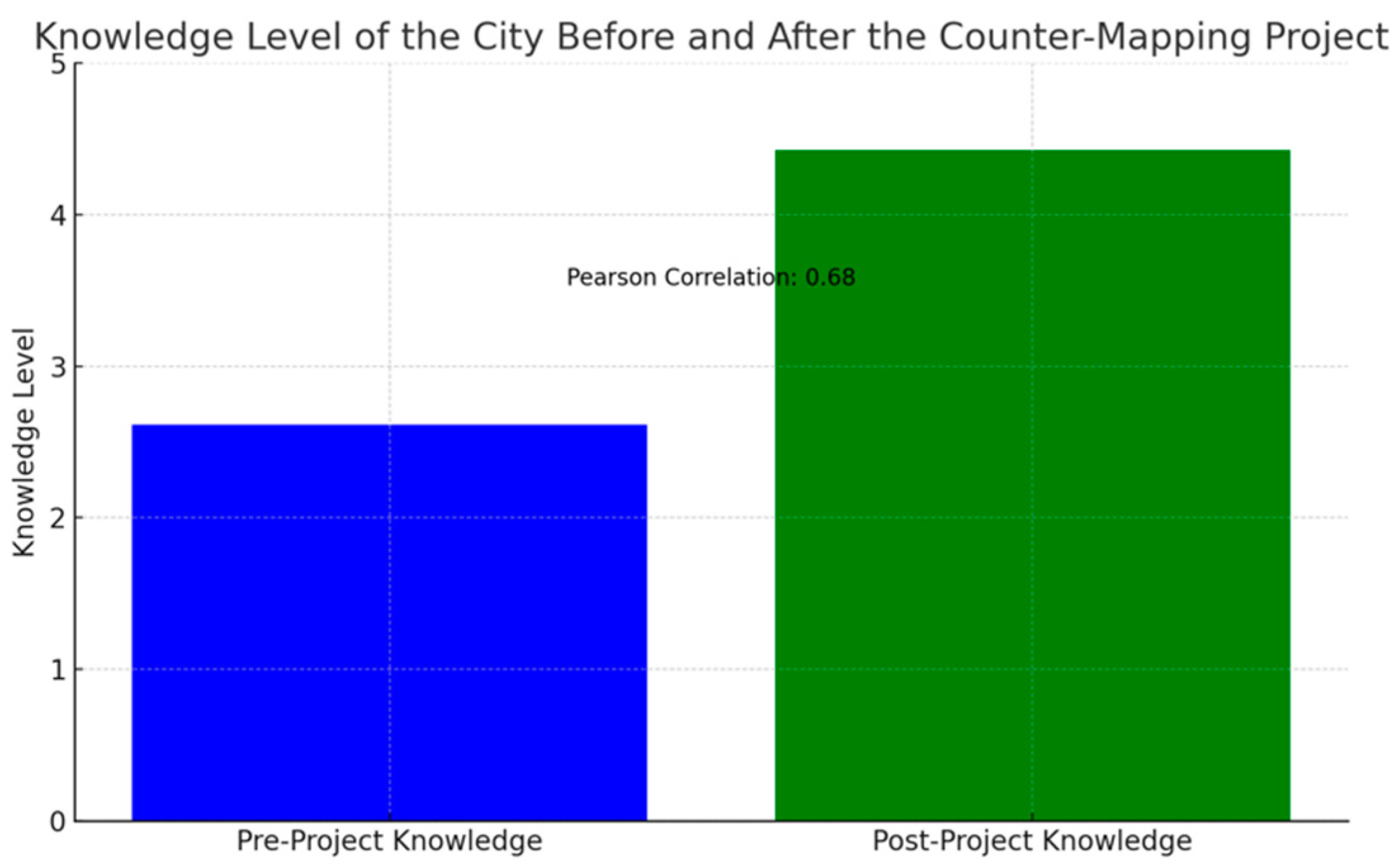

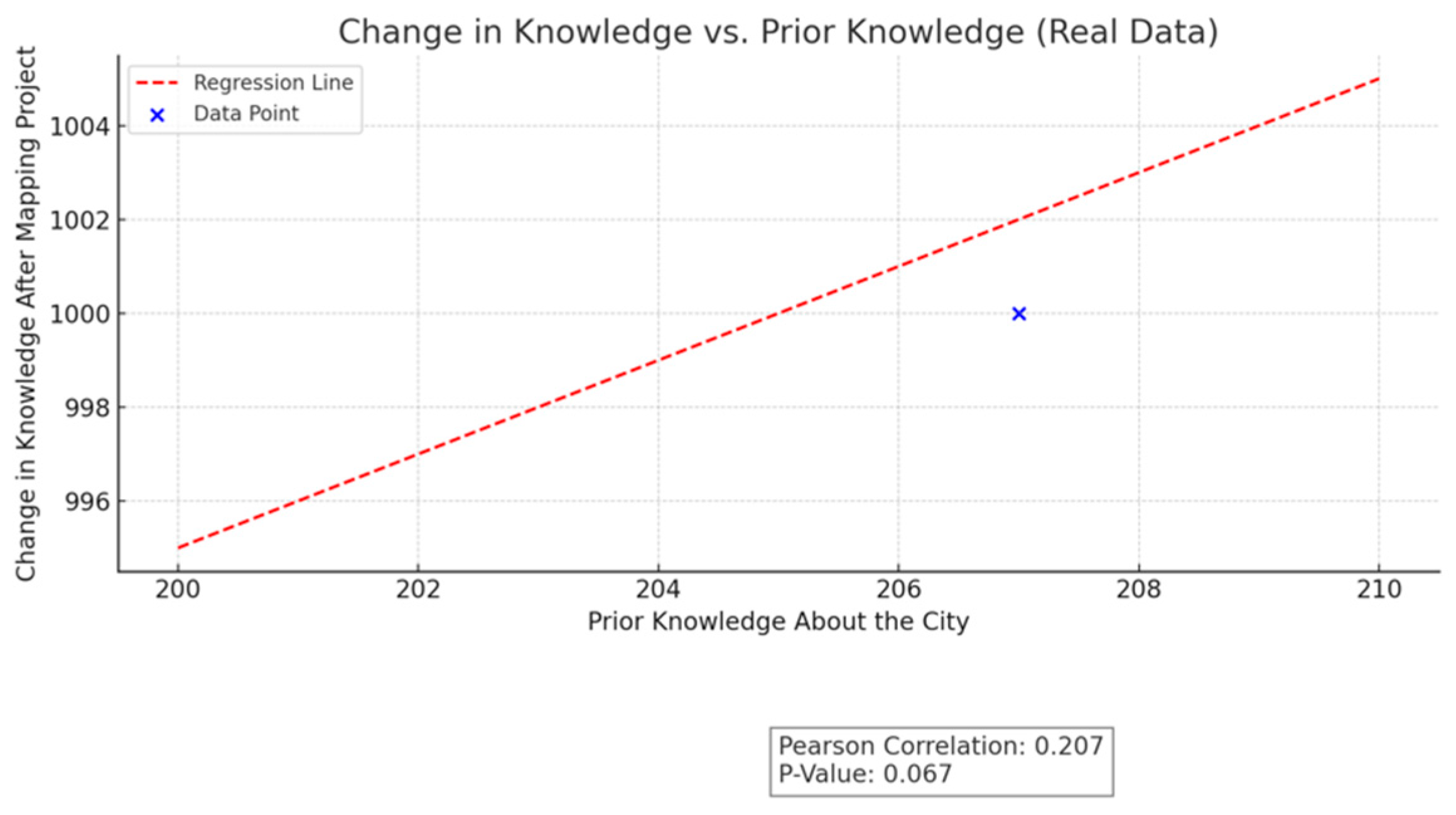

3.4. Regarding Whether the Degree of Prior Knowledge Influences the Level of Knowledge Gained after the Project

3.4.1. City Knowledge

As seen from the Wilcoxon test, there is a considerable increase in city knowledge after conducting the counter-mapping. But to what extent is this increase conditioned by prior knowledge? Investigating this link through Pearson’s correlation and non-parametric correlations of Kendall Tau_b and Spearman Rho can be relevant and shed light on the learning dynamics underlying the project (

Table 1).

The significant and robust correlation between prior knowledge and post-project acquired knowledge, indicated by a Pearson coefficient of 0.680, suggests that those students who had a more solid initial knowledge about the city tended to enrich and deepen their understandings throughout the project. This is reflected in the personal narratives of the students, where those with prior familiarity with the city, through residency or previous interest, describe a learning process that deepens and expands their existing knowledge, often in surprising areas they did not anticipate.

On the other hand, students who started the project with little or no knowledge about the city report a significant enrichment of their historical and cultural understanding, driven by research activities and direct interactions with the urban space and its inhabitants (

Figure 5). This demonstrates that the counter-mapping project catalyzed discovery and exploration, allowing these students to build a knowledge base from scratch.

The experiences described by students from the qualitative analysis of open-ended questions (

Table 2), such as interviewing city residents, exploring historical and cultural sites, and participating in research activities, illustrate how the learning process was influenced by a combination of fieldwork, community interaction, and personal reflection. This multifaceted approach seems to have fostered deeper and more contextualized learning, where the acquired knowledge is intimately linked to personal experiences and the perception of urban space.

3.4.2. Perception of Everyday Life

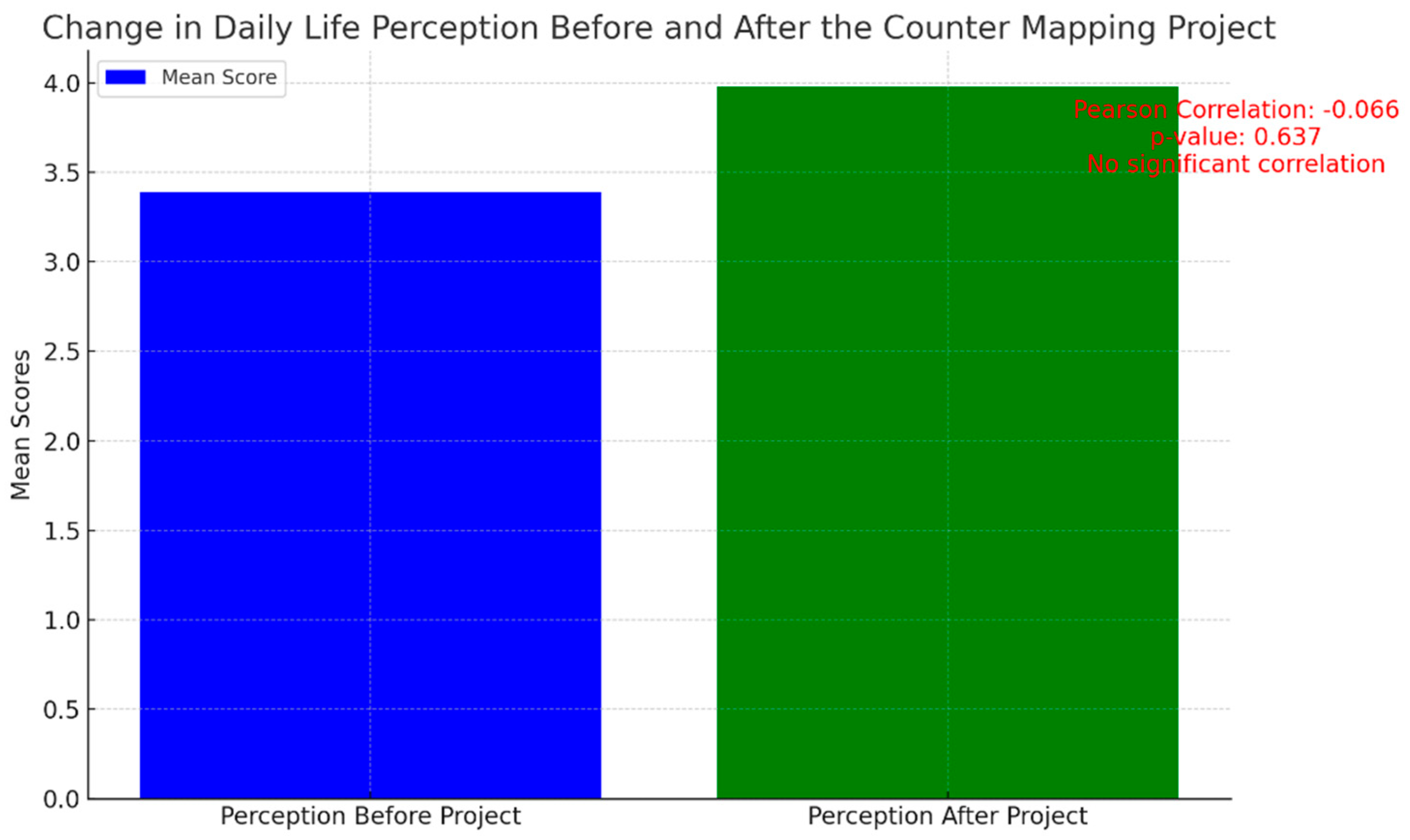

The low and non-significant correlation between perceptions of everyday life before and after the project, reflected in quantitative results, indicates that participation in counter-mapping has significantly altered students’ perceptions (

Figure 6). This variability in responses and the lack of a strong correlation suggest that the project achieved its objective of changing perceptions on a specific subject, in this case, the everyday experience of urban life.

The diversity of individual experiences and perceptions highlighted in the qualitative analysis (

Table 3) underscores how the project fostered a more nuanced and deepened understanding of the city, beyond previous conceptions based on assumptions or superficial knowledge.

After the project, according to qualitative analysis, a significant change in students’ perceptions is observed, reporting increased awareness and understanding of the complexity of everyday life in the city. This change is evidenced in the more critical evaluation of aspects such as the distribution and accessibility of urban services, the inclusion or exclusion of certain social groups, especially the elderly, and the identification of tensions between economic development and urban quality of life. Students highlight how the project allowed them to discover “the lived city,” i.e., the everyday experience of its inhabitants, through direct interaction with the urban space and its residents. This discovery manifested in identifying social gathering areas, evaluating the supply and demand of leisure and cultural spaces, and reflecting on the dynamics of social inclusion and exclusion.

3.4.3. Influence of the Information from the Invisible City

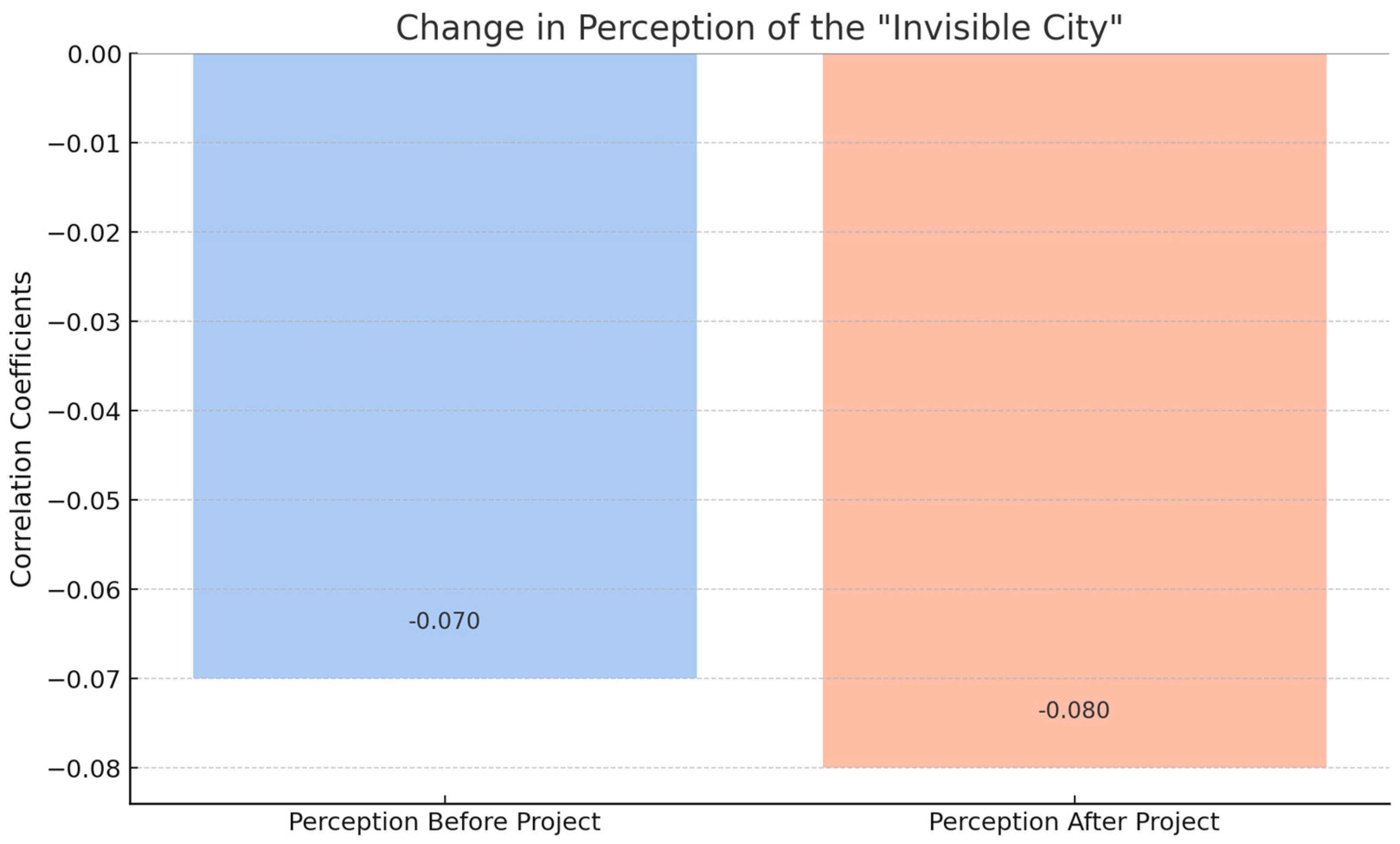

The low correlation between perceptions before and after the project, according to quantitative analyses, suggests that the project was effective in changing participants’ perceptions (

Figure 7). This change is not reflected in a strong linear relationship between pre- and post-project perceptions, indicating that counter-mapping has provoked a significant reevaluation of how students understand official information and its impact on city perception.

After participating in the counter-mapping project, students reported through qualitative analysis a greater awareness and understanding of the existence of an “invisible city” and the mechanisms by which official information may contribute to its concealment (

Table 4). They identified specific aspects where official information has omitted or minimized certain urban realities, leading to a loss of city identity or the invisibility of certain societal sectors. This change in perception reflects a deeper understanding of urban life complexities and the importance of considering all voices and experiences within the city.

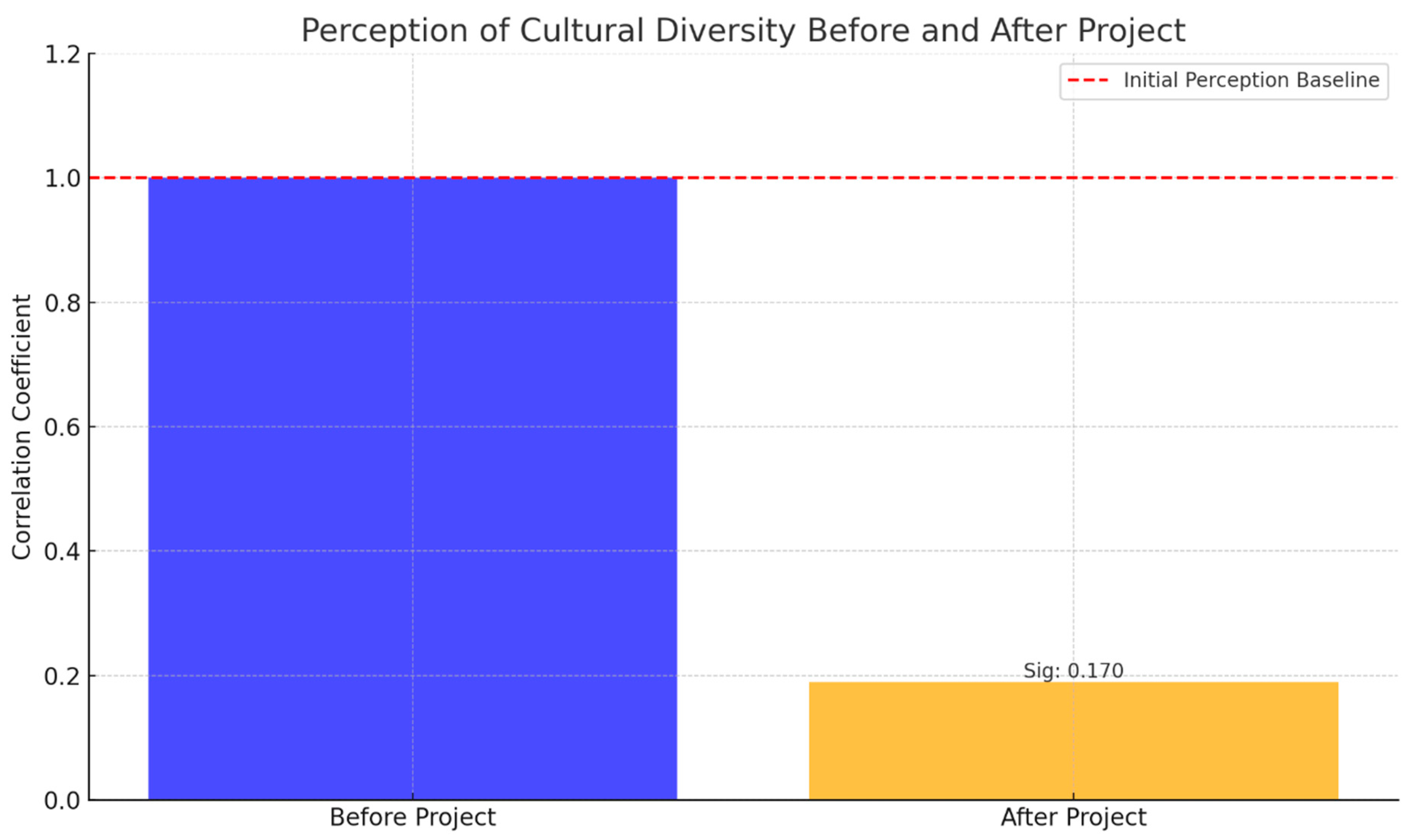

3.4.4. Perception of Cultural Diversity Before and After the Project

Through participation in the counter-mapping project, students began to recognize and value the richness of cultural and social diversity present in their environments (

Table 5). They identified specific areas within their cities that operate with their dynamics, highlighting how these spaces offer services, traditions, and forms of social interaction that differ from other parts of the city. The project allowed them to discover “cities within a city,” recognizing the importance of these micro-communities for the broader social and cultural fabric.

This transformation in students’ perceptions aligns with quantitative results that showed a moderate correlation in the perception of cultural diversity before and after the project (

Figure 8). This moderate change suggests that initial perceptions were not completely displaced but were enriched and expanded, reflecting a learning process that adjusts and deepens previous understanding without completely discarding it.

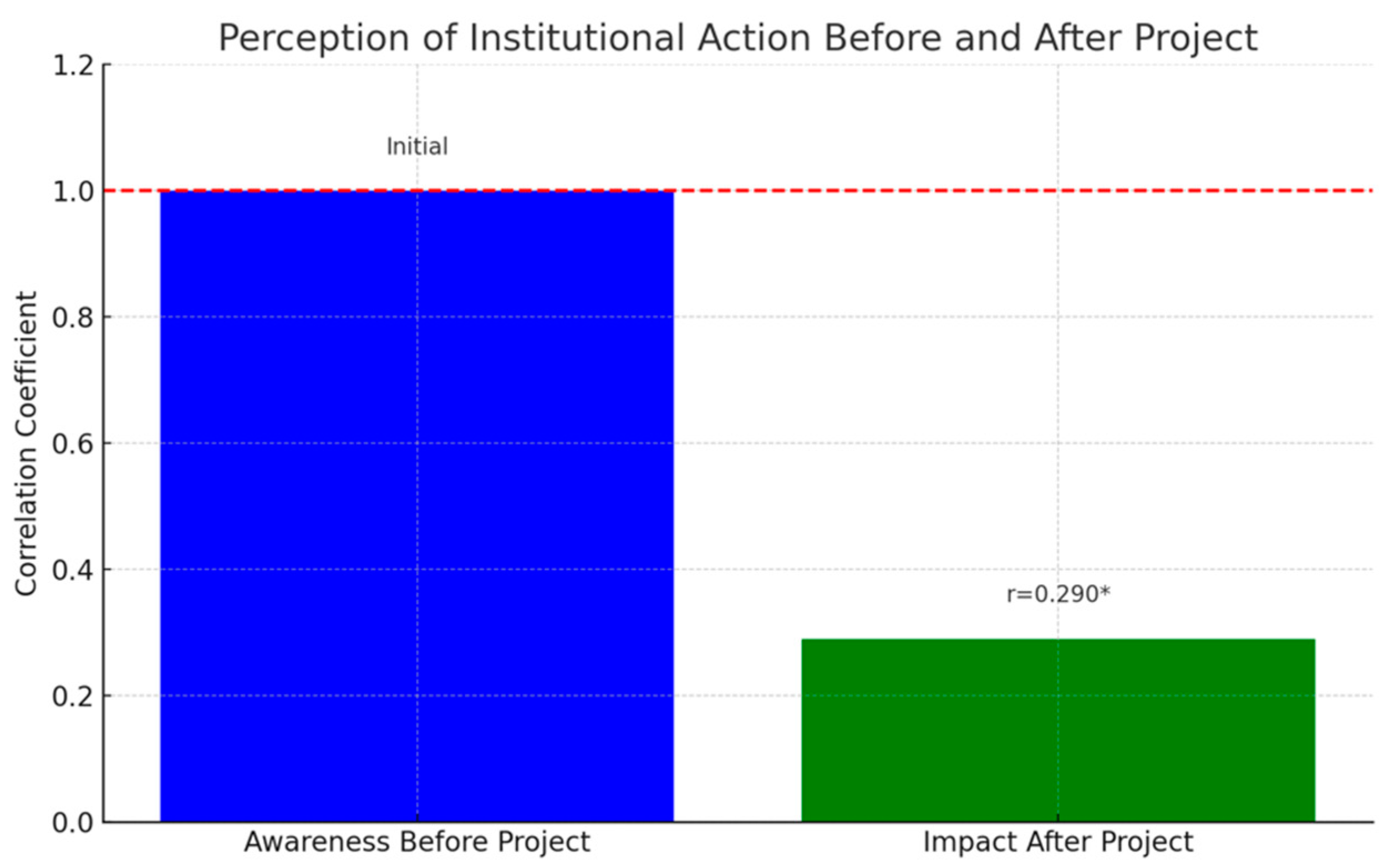

3.4.5. Perception Between Transformative Action at the Institutional Level Before the Project and Institutional Commitment After the Project

Before the project, awareness of specific needs for change in their communities varied, with some students pointing out the lack of adequate infrastructure, insufficient services, and social issues requiring attention. This variability in initial perception suggests that, while there was a general awareness of the need for change, the level of commitment and specific understanding of how to contribute to that change was limited.

Students’ responses (

Table 6) reflect a wide range of concerns, from the need to improve public transportation and cultural infrastructure to addressing vulnerable groups such as the elderly and including adequate leisure spaces for youth. The lack of knowledge or passivity towards these issues before the project indicates that, although there was a perception of need, it did not necessarily translate into active action or commitment.

The moderate correlation found quantitatively supports this evolution, suggesting that the project catalyzed greater engagement with institutional change, aligning with an improved perception of personal and collective capacity to influence urban dynamics (

Figure 9).

Despite this positive evolution, the moderation of the correlation also points to a diversity in the change experience among participants, consistent with varied responses about their level of awareness and commitment before the project. This underscores the complexity of influencing perceptions and attitudes towards institutions and the importance of differentiated strategies that consider individual and collective experiences to foster deeper and sustained engagement with transformative actions at the institutional level.

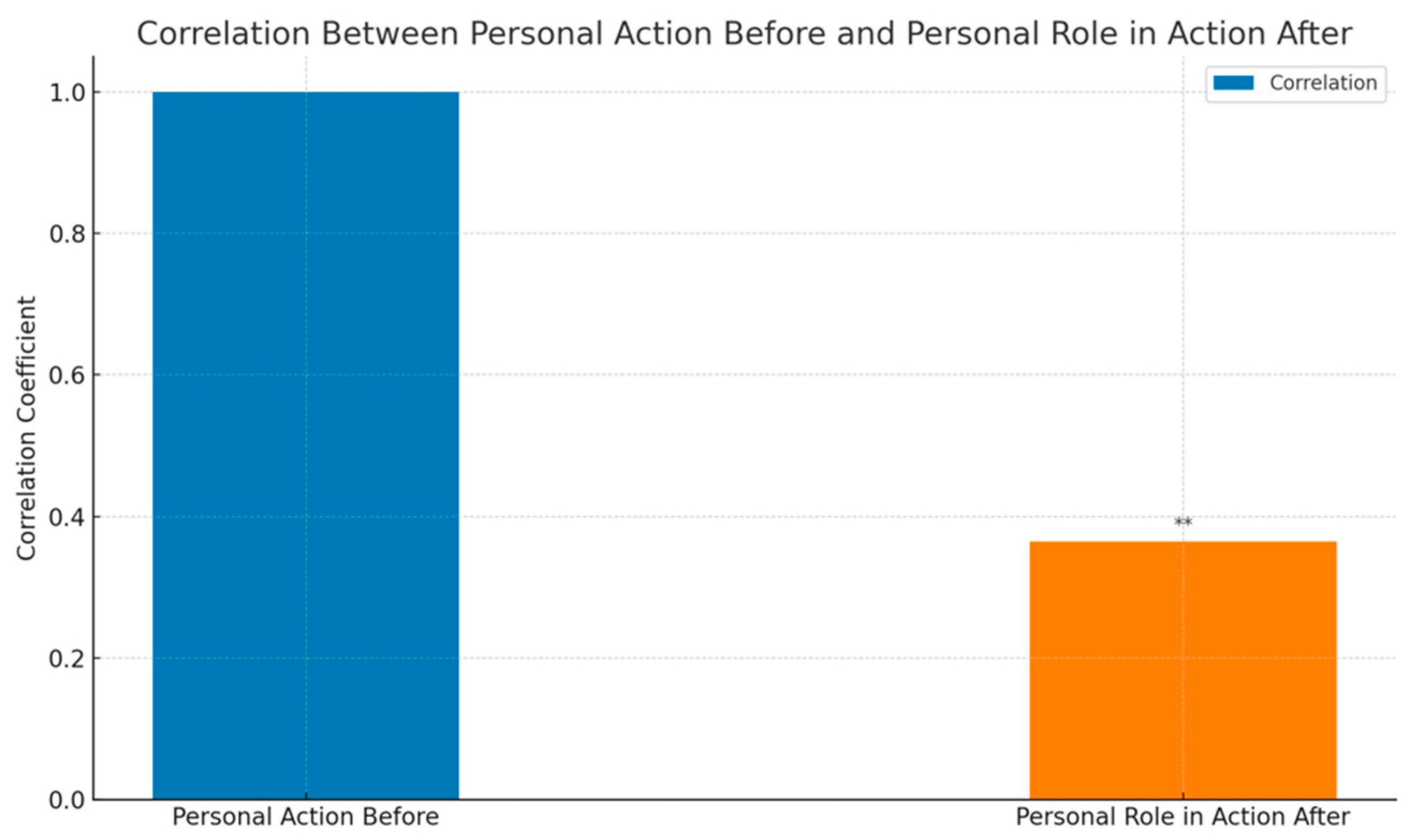

3.4.6. Perception Between Personal Transformative Action and Personal Commitment Before and After

The moderate correlation underscores the significant impact that the initiative has had on participants (

Figure 10). This link suggests that the activities and experiences proposed within the project framework have motivated participants to engage more deeply with the issues addressed, indicating that the project has been effective in fostering a change in perceptions and behaviors. The presence of a positive correlation, although not extremely high, implies that the project has succeeded in promoting critical reflection among participants, encouraging them to reconsider their level of personal commitment in an informed and autonomous manner. This result is essential for achieving sustainable and meaningful changes, as it reflects not just a change in participants’ attitudes, but also in their willingness to act by these new perceptions.

The correlation indicates that the project has been successful in promoting greater active participation in relevant issues, crucial for empowering participants and effective community action. This increase in personal commitment suggests that participants are now more prepared and motivated to actively engage in actions related to the topics addressed by the project.

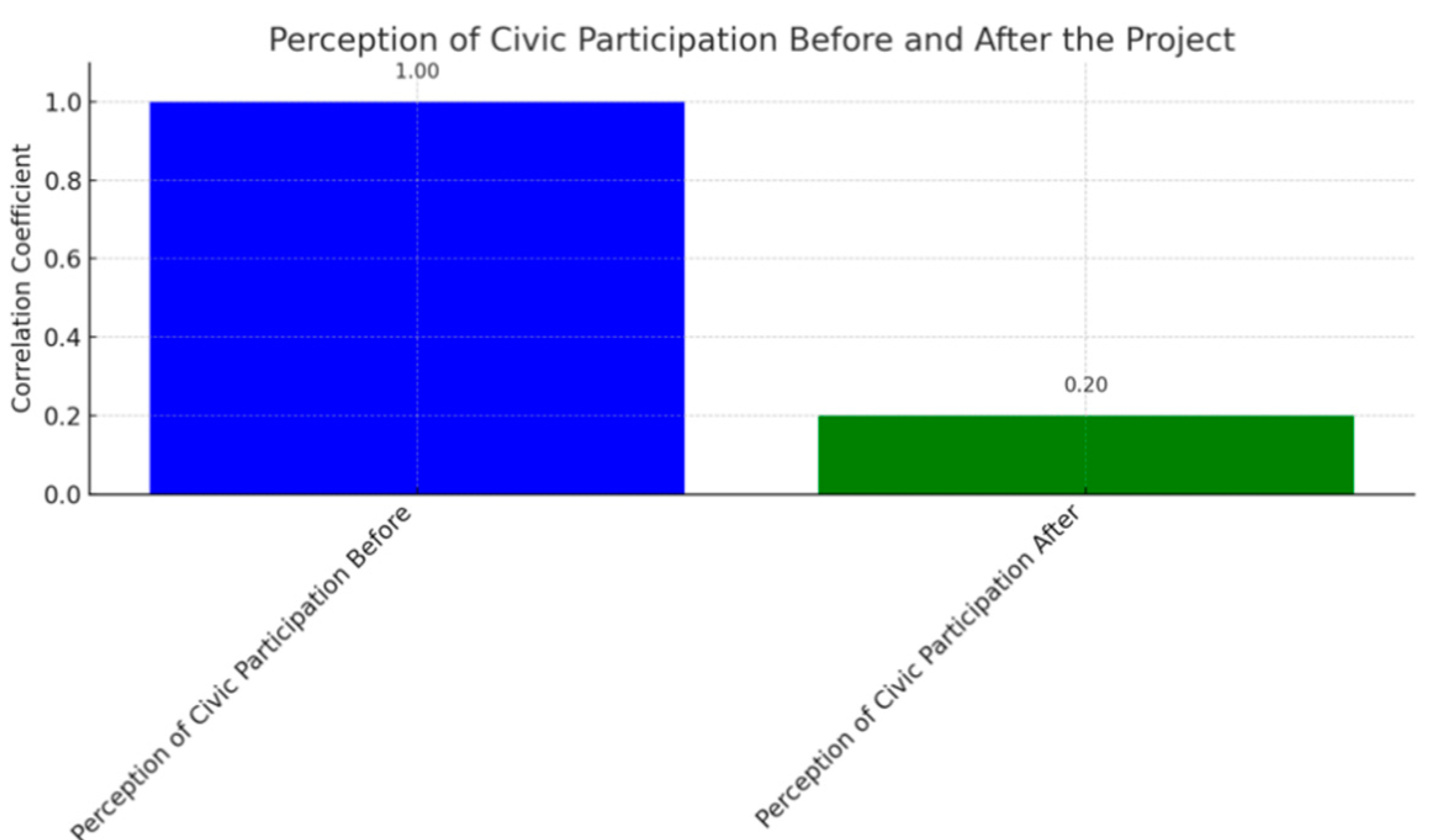

3.4.7. Perception Between Civic Participation Before the Project and the Perceived Importance of Participation After the Project

Participants have identified a range of urban issues, from the lack of adequate infrastructure and services to the need for social inclusion and environmental improvements. They conclude that collective action and personal commitment are essential for addressing these challenges, aligning with the moderate correlation found in the quantitative analysis between personal transformative action before the project and personally after the project (

Figure 11).

This correlation reflects a change in participants’ attitudes, who initially might not have felt fully empowered or aware of their potential to influence change. Participation in the project has catalyzed increasing their understanding that civic participation is crucial for sustainable development and improving the quality of life in their cities. Examples provided by students, ranging from the need for leisure spaces to the improvement of public services and the inclusion of vulnerable groups, underline the diversity of areas in which they see a need for change.

This awareness translates into a greater commitment to specific actions that can contribute to urban transformation. Participants express a greater willingness to get involved in community initiatives, from proposing improvements to participating in awareness-raising and cleanup activities (

Table 7). This commitment reflects an understanding that transformation depends not just on authorities but also requires active and propositional participation from citizens.

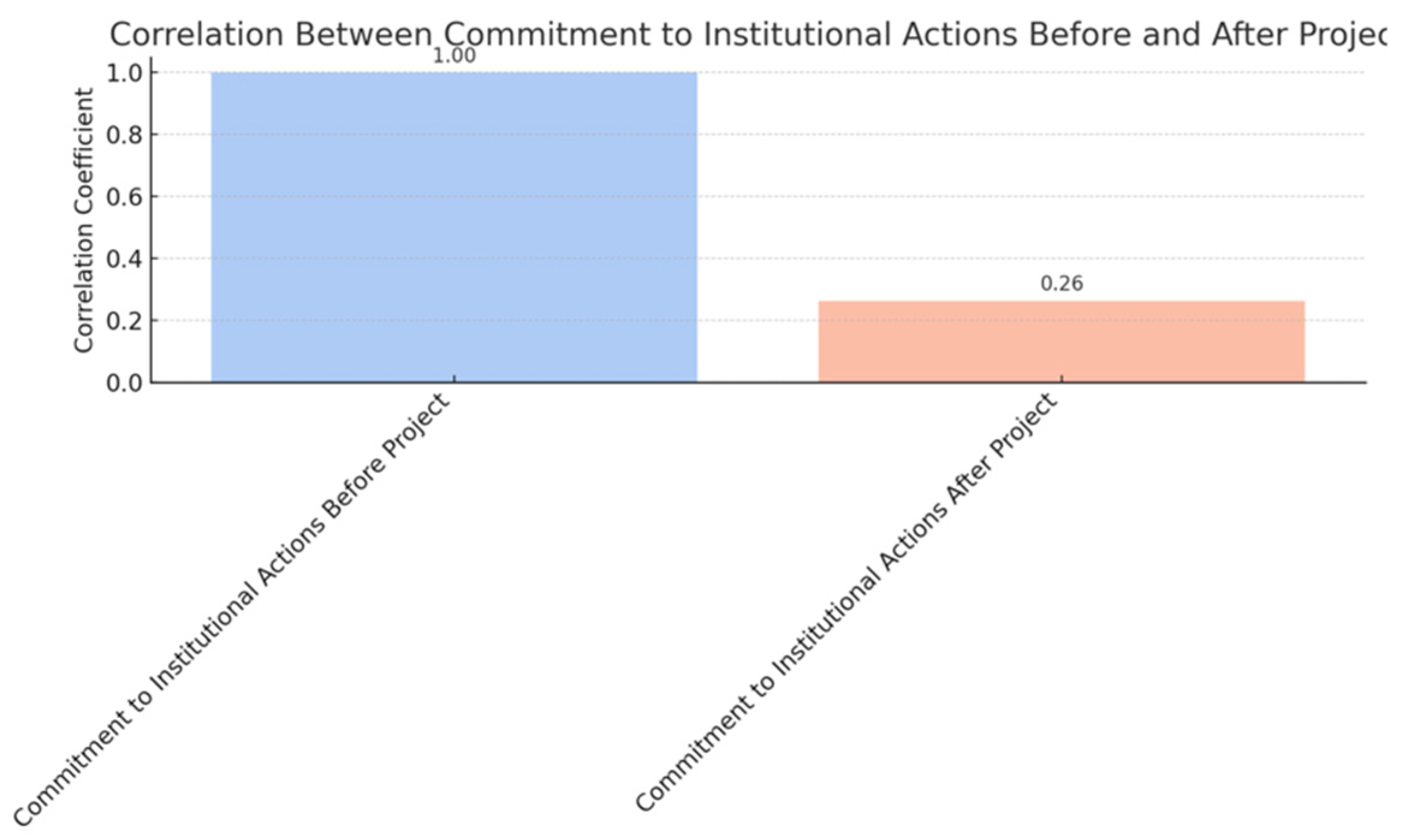

3.4.8. Perception Between Commitment to Institutional Actions Before and After the Project

Although the quantitative correlation between institutional commitment before and after the project is moderate (

Figure 12), qualitative narratives suggest a profound impact on individual and collective perceptions of the capacity to influence social and urban change (

Table 8).

Testimonies reveal a broad spectrum of concerns, from the need to improve public infrastructure to promoting social inclusion and support for youth and the elderly. The identification of these issues underscores a change in participants’ perceptions of their role in promoting transformative actions, evidencing a shift towards a deeper commitment to collective well-being and improving urban quality of life.

The analysis suggests that the project has catalyzed reflection and commitment to change, promoting greater awareness of the interdependence between citizens and institutions in creating more inclusive, sustainable, and livable cities. This increase in the perception of the need for active participation in transformative actions is reflected in participants’ desire to contribute to concrete solutions and seek constructive dialogue with institutions.

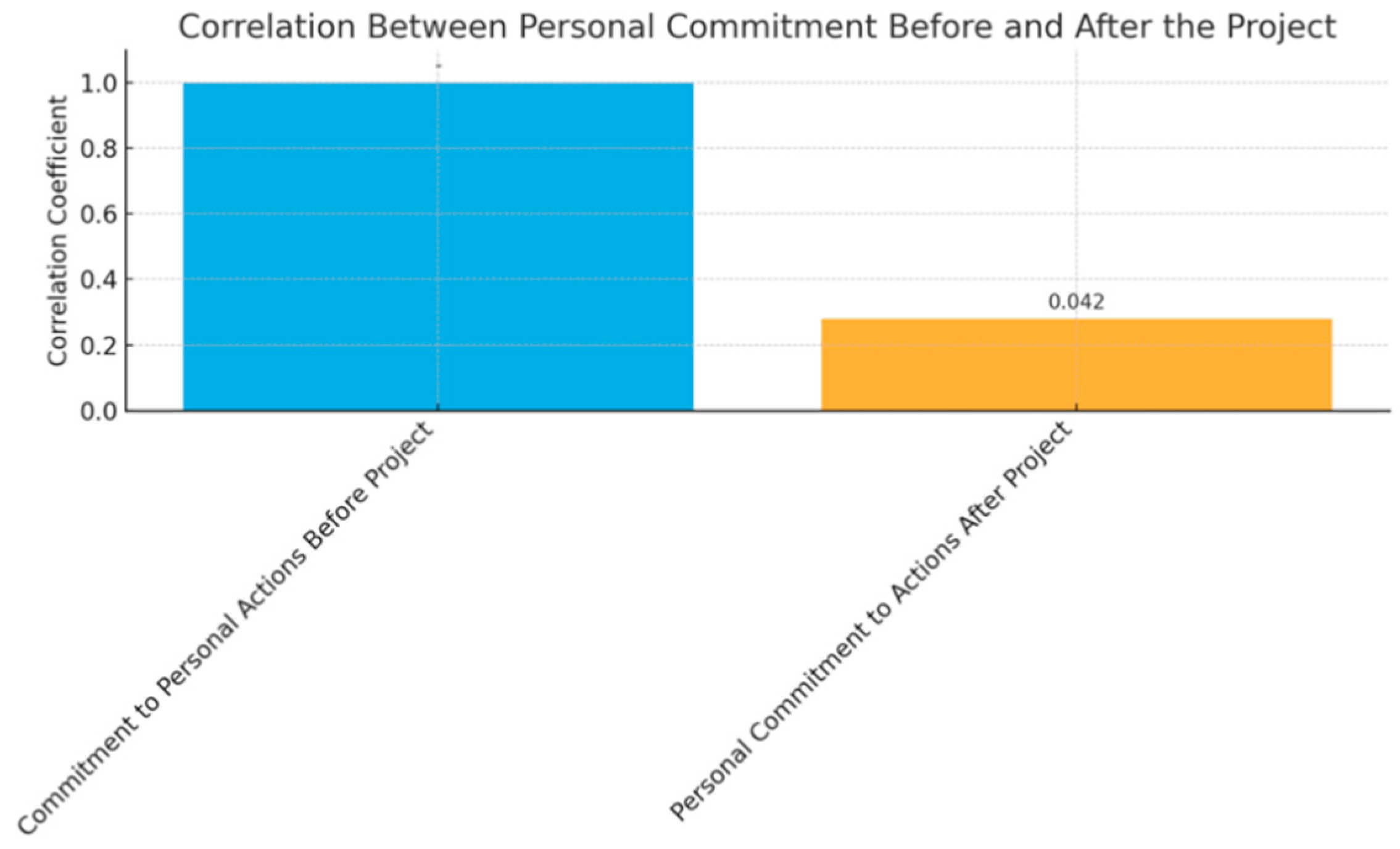

3.4.9. Perception Between Commitment to Personal Actions Before and After the Project

The correlation identified between participants’ commitment before the project and the change in this commitment after its conclusion, with a Pearson correlation of 0.278, underscores a positive, although moderate, impact of the project on personal commitment (

Figure 13). This result suggests that the project has fostered an increase in personal commitment, although the magnitude of this impact varies among participants. This variability implies that individual experiences and reactions to the project are heterogeneous, possibly influenced by a variety of personal factors.

The moderate significance of this correlation indicates that the project has been able to reinforce or enhance the existing personal commitment in some participants, rather than establishing a new level of commitment in those who initially did not demonstrate it. Therefore, while a positive effect is acknowledged, there is a clear potential to intensify this impact. This point is of utmost importance for the ongoing evaluation and improvement of the project, suggesting the need for adjustments in the proposed activities or methodological approaches to increase personal commitment among participants. In any case, this result validates the project’s direction toward its goals of positively influencing participants’ perceptions and behaviors.

3.4.10. Perception Between General Knowledge Before the Project and After

Before starting the project, many participants had limited knowledge or focused on tourist and superficial aspects of their cities. Participation in the project allowed them to discover the richness of local history, the importance of cultural traditions and festivities, and the existence of social and economic problems affecting their communities. The counter-mapping methodology, based on participatory research and interviews with residents, provided students with tools to explore and understand urban dynamics from a more inclusive and deep perspective.

This change in perception and knowledge was not dependent on the initial knowledge level of participants (

Figure 14), aligning with quantitative findings indicating a lack of significant correlation between general knowledge before the project and the change in this knowledge after its completion (

Table 9). This result suggests that the project impacted participants equitably, regardless of their starting point regarding knowledge about the city.

The counter-mapping experience fostered greater awareness of the diversity of urban experiences and emphasized the importance of considering varied perspectives in urban analysis and planning. The specific moments highlighted by participants, such as interviews with residents and exploration of lesser-known areas of the city, contributed to a significant change in how they perceive and value their urban environment.

This qualitative analysis highlights the project’s ability to promote meaningful learning and critical reflection on urban spaces, beyond mere knowledge accumulation. By challenging previous perceptions and fostering an empathetic and reflective approach to the city, the project has enriched participants’ understanding of the complexity and richness of their urban environments, preparing them to contribute more informedly and committedly to civic and community life.

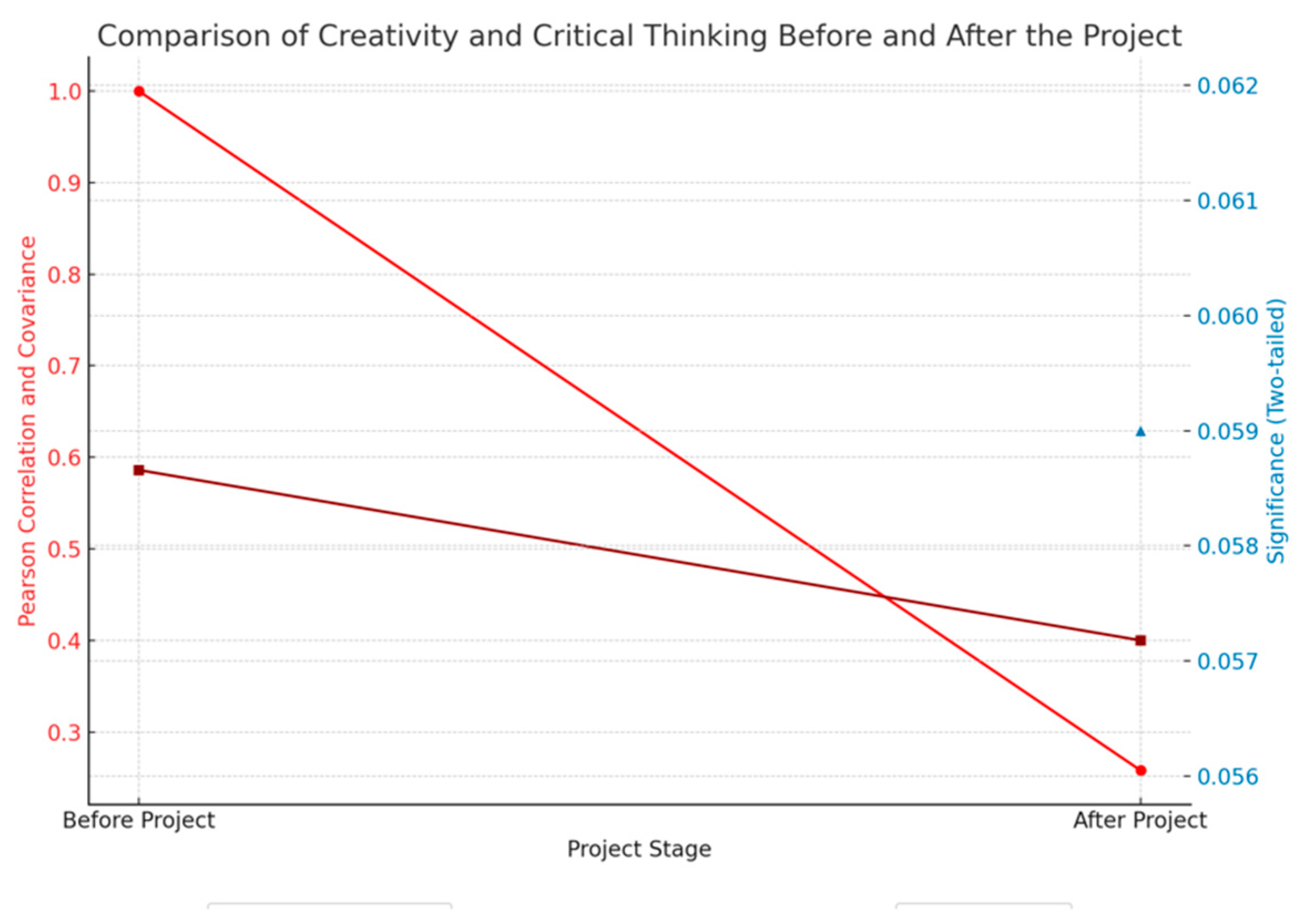

3.4.11. Perception Between Level of Creativity and Critical Thinking Before and After the Project

The positive but low correlation between levels of creativity and critical thinking before and after the project, according to quantitative data, finds an echo in students’ qualitative responses. Although improvement is evident, variability in individual perceptions suggests that additional factors, such as personal interest, motivation, and group dynamics, could significantly influence learning outcomes.

Students report an advancement in their ability to critically analyze information, contrast sources, and reflect on urban issues from diverse perspectives. This demonstrates that the project has been a catalyst for critical evaluation of data and fostering a deeper awareness of social and urban dynamics. Collaboration and idea exchange among peers appear as key elements in the learning process. This group dynamic not only enhanced creativity and critical thinking but also provided a supportive environment where students could collectively overcome the challenges inherent in the project.

Figure 15 shows the correlation between the level of creativity and critical thinking before and after the project. Additionally, it illustrates the variability and change in these measures over time with a scatter plot including regression lines before and after the project to highlight the correlation and changes in covariance. This visual highlights how the project has impacted students’ levels of creativity and critical thinking.

Most students did not anticipate the extent to which their participation in the counter-mapping project could enrich their creativity and critical thinking. This suggests that the experience exceeded prior expectations, emphasizing the importance of practical and interactive projects in the educational field for the development of cross-curricular competencies.

Personal narratives indicate a significant educational impact of the counter-mapping project, evidencing not only an increase in creativity and critical thinking skills but also a change in perception about the utility and applicability of what was learned in real contexts (

Table 10).

Several responses highlight how the challenge of synthesizing and representing complex information on a map enhanced students’ creativity. The need to be original in presenting their projects and creating didactic units illustrates how counter-mapping fosters innovative thinking and creative problem-solving.

3.4.12. Conclusions from Quantitative (Correlations) and Qualitative Analysis

The conclusion derived from integrating quantitative and qualitative analyses regarding the counter-mapping project underscores its effectiveness in enriching and transforming students’ knowledge and perception of their cities. Although quantitative correlations did not show marked statistical significance (

Table 11), which could initially suggest a lack of direct impact of prior knowledge on the learnings acquired during the project, the qualitative analysis reveals a different story. This comprehensive approach demonstrates that the project facilitated meaningful and deep learning, allowing participants to discover the hidden layers of their urban environments and better understand the complexities of life and challenges of their cities, regardless of their initial level of knowledge.

3.5. Change Variables

We have also analyzed the change in participants’ perception or knowledge level after their involvement in a counter-mapping project, using a Likert scale from 1 to 5.

The review of additional data provided by post-participation change variables in the counter-mapping project and its comparison with conclusions previously drawn from earlier quantitative and qualitative analyses allows for a deeper understanding of the project’s impact on participants. High responses on the Likert scale, especially in areas like the city’s historical and cultural knowledge, perception of everyday life, the influence of official information on revealing an “invisible city,” appreciation of cultural and social diversity, and change in the level of creativity and critical thinking, affirm the project’s effectiveness in promoting meaningful learning and a perceptual change among participants.

The variability in responses, while present, does not contradict previous conclusions but complements them, offering a more nuanced view of the project’s impact. Notably, despite this variability, averages indicate a general perception of improvement in all evaluated aspects. This suggests that the project achieved its goal of enriching participants’ knowledge and understanding of their urban environment, regardless of individual differences in prior experience or gender.

The analysis of gender differences in perception of change could have revealed specific nuances in how men and women experienced the project. However, the absence of significant gender differences in overall conclusions suggests that the project was equally effective for all participants, an important finding that confirms the universality and accessibility of the counter-mapping project as an educational tool.

The high levels of perceived change in historical and cultural knowledge, as well as in the perception of cultural and social diversity, reinforce the idea that the counter-mapping project not only increased students’ awareness of specific aspects of their cities but also fostered a deeper appreciation for the complexity and richness of urban spaces. This aligns with previous conclusions highlighting counter-mapping as an effective method for exploring and understanding the diversity and dynamics of cities from a critical and reflective perspective.

In terms of creativity and critical thinking, the perceived increase in these skills after participating in the project confirms and extends previous conclusions on the pedagogical value of counter-mapping. This finding underscores the project’s capacity not only to impart specific knowledge but also to develop critical thinking skills, essential for informed and active citizen participation.

3.6. Regression Analysis on Knowledge before and after Counter-Mapping

To summarize and present the extensive results of the regression analysis conducted on the impact of the counter-mapping project on different dimensions of learning and perception, we have produced

Table 12.

An example is a scatter plot with a regression line (

Figure 16) on the “Change in historical and cultural knowledge”; documented as variable #1 in Table 13. This visual approach directly visualizes the correlation between prior knowledge (independent variable) and the change in knowledge (dependent variable), allowing identification of trends and the strength of the relationship.

As seen in

Figure 16, the Pearson Correlation is 0.207, indicating a weak positive correlation between prior knowledge and change in knowledge, which is consistent with the analysis provided. The P-Value of 0.067 suggests a trend towards statistical significance, though it does not meet the conventional threshold of 0.05, indicating that the relationship is not statistically significant at the conventional level. Therefore, this graph provides a visual representation of how, in this case, participants’ prior knowledge of the city’s history and culture has a weak influence on the change in their knowledge after the counter-mapping project, as also seen in the previously conducted Correlation analyses.

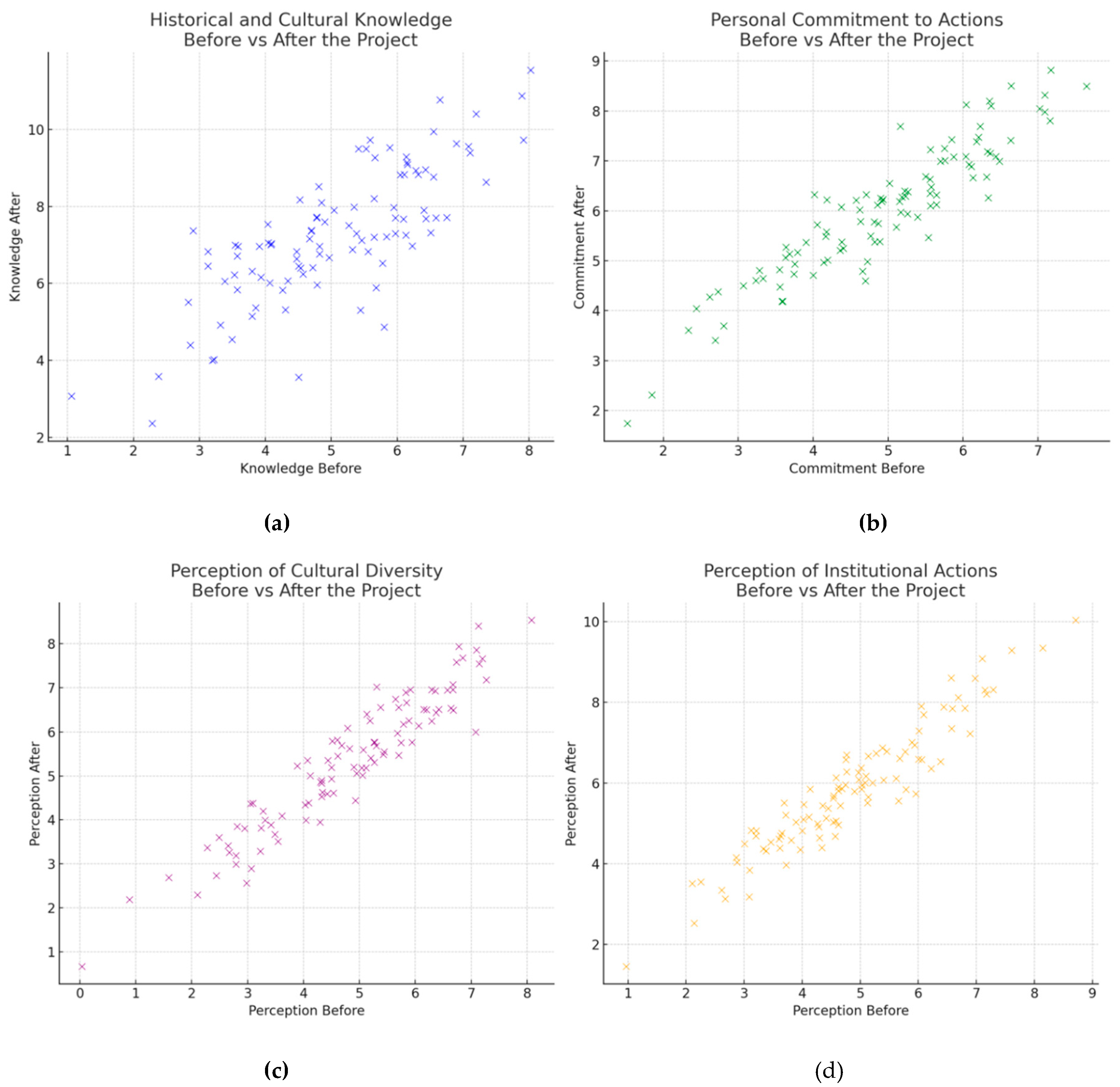

For

Figure 17, we have selected some of the most significant relationships to visualize in graphs (including the one treated in the previous figure). Thus, we have generated four graphs that effectively illustrate the significant relationships and patterns observed in the data.

In (a). Historical and Cultural Knowledge Before vs after the Project, a general improvement in participants’ historical and cultural knowledge following the counter-mapping project is observed. In (b). Personal Commitment to Actions before vs after the Project, illustrates the change in personal commitment to actions, indicating an increase in participants’ commitment as a result of their participation in the project. In (c). Perception of Cultural Diversity before vs after the Project, shows a slight increase in the perception of cultural diversity, indicating that participants may have developed a greater appreciation or awareness of the city’s cultural diversity as a result of the project. Lastly, in (d). Perception of Institutional Actions before vs after the Project, illustrates an increase in the perception of the importance and impact of institutional actions, suggesting that the project may have fostered greater awareness or valuation of the contribution of institutions in urban and cultural development. Therefore, it demonstrates how the counter-mapping project has impacted participants’ perceptions in different aspects, complementing previous analyses and providing a more complete view of the project’s impact.

This analysis ultimately emphasizes the complexity of the learning process, where prior knowledge emerges as a significant, but not exclusive, factor, reinforcing the need for educational interventions that are accessible and enriching for a broad spectrum of participants. It underscores the necessity to consider a range of influences and educational experiences beyond prior knowledge, promoting meaningful learning that is supported by both previous experiences and new learning opportunities offered by the project. The analysis also reveals that the educational impact of projects like counter-mapping cannot be measured solely in terms of knowledge acquisition. It is crucial to consider how these interventions alter individuals’ perceptions of their surroundings and how additional factors, outside the direct educational realm, can influence learning outcomes. This highlights the importance of adopting holistic pedagogical approaches that address both knowledge and perception to foster comprehensive change in participants. Moreover, there is a suggested need for more detailed research to understand the underlying mechanisms facilitating changes in perception of everyday life and other less direct aspects. The identification of atypical cases and the minimal relationship between certain prior and subsequent perceptions suggest individual variations in how participants respond to the project, warranting further exploration in future research.

4. Discussion

Very much in line with the counter-mapping project we have launched, Mèlich has examined the intersection between symbolic anthropology and education, highlighting how symbols and meanings are crucial in the construction of identities and subjectivities, which have direct implications for education [

101]. Jodi Dean, on the other hand, introduces the concept of “symbolic efficiency,” describing it as the capacity of symbolic systems to influence people’s perceptions and actions, generating ideological consensuses that favor the capitalist system. In this context, symbolic efficiency facilitates domination through consensus and persuasion, rather than coercion, establishing what is considered legitimate within society [

102,

103].

Dean argues that this system promotes an individualism that isolates and alienates, turning communication into a means for consumption rather than for collective construction and social transformation [

103]. However, despite the challenges of communicative capitalism, new pedagogical avenues (where we believe counter-mapping perfectly fits) that leverage digital communication and social networks to foster participation and collaboration in education are explored, thus promoting transformative pedagogical currents and collaborative learning in online communities.

The impact of education on socio-emotional development is fundamental to our project, due to its importance in fostering social and emotional skills along with academic knowledge [

104,

105]. Socio-emotional development encompasses the ability to manage emotions, establish positive relationships, make responsible decisions, and resolve conflicts, which are essential for success in school, work, and personal realms. Integrating socio-emotional education into the school curriculum has been shown to improve academic performance, emotional resilience, and psychological well-being, and reduce disruptive behaviors such as bullying [

106,

107]. Therefore, our approach aligns with the Pedagogy of Dialogue, which values participative communication and mutual respect in the educational process [

108,

109] and is inspired by Foucault’s notion of “parrhesia,” which promotes sincerity and critical thinking in education [

110,

111,

112,

113].

Fadel, et al. [

100] focus on 21st-century education and identifying the key skills students need to succeed in the current and future world. According to their research, key skills include the 4Cs: creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration. These skills are fundamental for preparing students to face the challenges of today’s and future world, and to succeed in a variety of fields and professions.

In the same vein, for Dantas-Whitney et al. [

106], educators must provide students with a framework for critical reflection, to better understand their students’ needs and create meaningful and relevant learning opportunities for them [

107].

In another vein, as our project has a subsequent phase of result analysis from both pretest and posttest surveys, it is important to know what critical pedagogy proposes in aspects related to research in Education in general and the study of narratives in particular. McLaren [

109] examines the relationships between critical theory and educational research. In the context of educational research, critical theory is applied to examine and question existing educational practices and teaching systems. It is interested in understanding how educational institutions can reproduce social inequalities and how they can be transformed to promote equity and liberation.

Hence, from the critical approach, qualitative research seeks to question power structures and inequalities in the field of study. Gallagher [

114] examines the tensions and dilemmas researchers face when conducting qualitative research, especially about critical, creative, and post-positivist perspectives. Jackson & Mazzei [

115] focus on the concept of “voice” in qualitative research and challenge conventional, interpretive, and critical conceptions of how it is understood and applied in this field. Kincheloe, et al. [

116], likewise, address the relationship between critical pedagogy and qualitative research. Davis [

117] also highlights the importance of participants’ voices in qualitative research and how it can be used to inform and promote more inclusive and equitable educational policies and practices.

More recently, Wang [

118] focuses on promoting qualitative research methods to foster critical reflection and change in various fields of study. Moreover, Wang emphasizes the importance of using qualitative research as a tool for social change and transformation [

118]. Finally, Díaz, et al. [

119] have focused on the applicability of critical qualitative methodology in addressing research on the development of critical thinking through critical debate as a pedagogical strategy.

5. Conclusions

The counter-mapping project has proven to be a valuable pedagogical tool, capable of transcending the limitations of traditional teaching methods by providing students with a platform to explore, question, and reimagine their relationship with urban space. In doing so, it has fostered not only multidimensional learning but also the development of critical skills such as analytical thinking, active research, and effective communication. These are essential competencies in an increasingly urban and globalized world, where understanding and acting upon social and spatial dynamics becomes an integral part of civic education.

Through a methodology that combines field research, interviews, and reflective analysis, participants have achieved a more nuanced understanding of the complexity and richness of urban spaces. This approach has allowed not only for an increase in awareness of specific historical and cultural aspects but also for the promotion of an appreciation for cultural and social diversity, as well as the development of critical skills essential for active and committed citizenship that can be very useful for the subsequent development of projects related to tourism, cultural promotion, social action, urban planning, etc.

The project’s effectiveness in inducing significant changes regardless of participants’ prior knowledge underscores its value as an inclusive tool, capable of adapting to and enriching a diversity of experiences and knowledge. Therefore, we can conclude that both quantitative and qualitative analyses provide a complex perspective on the project’s impact, revealing that prior knowledge is a significant but not exclusive factor in the learning process.

Figure 2.

Descriptive analysis of knowledge variables after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 2.

Descriptive analysis of knowledge variables after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation for each pair of samples before and after the counter-mapping project. Source: Authors’ elaboration. A horizontal line at y=0 helps to differentiate between positive and negative correlations.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation for each pair of samples before and after the counter-mapping project. Source: Authors’ elaboration. A horizontal line at y=0 helps to differentiate between positive and negative correlations.

Figure 4.

Means and standard deviations for two evaluation points: “Knowledge Level of the City Before Project” and “Knowledge Level of the City After Project”. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 4.

Means and standard deviations for two evaluation points: “Knowledge Level of the City Before Project” and “Knowledge Level of the City After Project”. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the level of city knowledge before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the level of city knowledge before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 6.

Correlation on the perception of everyday life before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 6.

Correlation on the perception of everyday life before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 7.

Correlation on the perception of the influence of information from the Invisible City, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 7.

Correlation on the perception of the influence of information from the Invisible City, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 8.

Correlation on the perception of cultural diversity, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 8.

Correlation on the perception of cultural diversity, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 9.

Correlation on the perception of institutional action, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 9.

Correlation on the perception of institutional action, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 10.

Correlation on the perception of institutional action, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 10.

Correlation on the perception of institutional action, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 11.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project.Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 11.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project.Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 12.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 12.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 13.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 13.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 14.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 14.

Correlation on the perception of civic participation, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 15.

Comparison of creativity and critical thinking, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 15.

Comparison of creativity and critical thinking, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 16.

Significant relationships and patterns were observed in regressions, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 16.

Significant relationships and patterns were observed in regressions, before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 17.

Significant relationships and patterns were observed in regressions, before and after the project. (a). The relationship between historical and cultural knowledge before and after the project, (b). The change in personal commitment to actions before and after the project, (c). Perception of Cultural Diversity Before vs After the Project, (d). Perception of Institutional Actions Before vs After the Project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 17.

Significant relationships and patterns were observed in regressions, before and after the project. (a). The relationship between historical and cultural knowledge before and after the project, (b). The change in personal commitment to actions before and after the project, (c). Perception of Cultural Diversity Before vs After the Project, (d). Perception of Institutional Actions Before vs After the Project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Table 1.

Correlations on city knowledge before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Table 1.

Correlations on city knowledge before and after the project. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

| |

Historical and Cultural Knowledge Level Before the Project |

Historical and Cultural Knowledge Level After the Project |

| Historical and Cultural Knowledge Level Before the Project |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

,680 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) |

|

<,001 |

| Sum of Squares and Cross-Products |

74,833 |

22,944 |

| Covariance |

1,412 |

,433 |

| N |

54 |

54 |

| Historical and Cultural Knowledge Level After the Project |

Pearson Correlation |

,680 |

1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) |

<,001 |

|

| Sum of Squares and Cross-Products |

22,944 |

15,204 |

| Covariance |

,433 |

,287 |

| N |

54 |

54 |

| . The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). |

Table 2.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Level of historical and cultural knowledge before and after the project”. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Table 2.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Level of historical and cultural knowledge before and after the project”. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

| 2. What WAS your level of historical and cultural knowledge of that city before? Would you highlight anything specific that you knew before undertaking the project? |

| 5. Can you share some of the specific experiences or activities that contributed to your increased historical and cultural knowledge of your city AFTER your participation in the counter-mapping project? |

Table 3.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of everyday life before and after the project.”.

Table 3.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of everyday life before and after the project.”.

| 7. What was your perception BEFORE of everyday life in the city and its relationship with the tourist, economic, social, or cultural experience that you have highlighted from it?” |

| 10. Can you share some of the specific experiences or activities of the Lived City that influenced your perception of everyday life in the city AFTER your participation in the counter-mapping project? |

Table 4.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of the concealment of the ‘invisible city’ before and after the project.”.

Table 4.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of the concealment of the ‘invisible city’ before and after the project.”.

| 12. Were you aware BEFORE the counter-mapping that official information could be generating the existence of an ‘invisible city’ in your environment? If so, can you provide examples or reasons that led you to this reflection (BEFORE counter-mapping)? |

| 15. Can you share your reflections and observations after your participation in the research of the Invisible City? Have you identified any specific aspect in which official information has contributed to hiding an “invisible city,” to the loss of city identity, or to the invisibility of certain sectors of society in the city? |

Table 5.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of cultural diversity before and after the project.”.

Table 5.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of cultural diversity before and after the project.”.

| 17. What reflections did you have, BEFORE the counter-mapping project, about cultural and social diversity? Did you consider the possibility of there being ‘cities within a city’? |

| 20. Can you share your reflections and observations after your participation in this research project? Have you identified any specific aspect in which the research influenced your perception of cultural and social diversity in the “cities within the city” or its importance for community development? |

Table 6.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Awareness of the need for institutional actions before and after the project.”.

Table 6.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Awareness of the need for institutional actions before and after the project.”.

| 26. Provide specific examples (if any) of situations or experiences that influenced your perception of the need for transformative actions in your city BEFORE counter-mapping. |

| 27. Can you share examples of situations or events that led you, BEFORE counter-mapping, to consider your role in implementing transformative actions in your city? |

Table 7.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of civic participation before and after the project.”.

Table 7.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Perception of civic participation before and after the project.”.

| 34. Can you share examples of how your participation in the project has influenced your perception of the importance of civic participation in transforming your city? |

Table 8.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Commitment to institutional actions before and after the project.”.

Table 8.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Commitment to institutional actions before and after the project.”.

| 33. Can you provide specific examples of situations or experiences within the project that have influenced your perception of the need for transformative actions in your city? |

Table 9.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “General knowledge and perception before and after the project.”.

Table 9.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “General knowledge and perception before and after the project.”.

| 36. Is there any particular aspect of your knowledge or perception of the city that you consider important before starting the project? |

| 39. Can you share some of the specific experiences or moments that contributed to your change in knowledge and perception of the city during your participation in the counter-mapping project? |

Table 10.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Level of creativity and critical thinking before and after the project.”.

Table 10.

Qualitative Analysis. Open-ended questions on the variables “Level of creativity and critical thinking before and after the project.”.

| 41. How did you honestly expect, BEFORE counter-mapping, that your participation in the project would impact your level of creativity and critical thinking? |

| 44. Can you share some of the specific experiences or activities that contributed to your development of creativity and critical thinking during your participation in the counter-mapping project? |

Table 11.

Summary of correlations, before and after the project, and their consequences.

Table 11.

Summary of correlations, before and after the project, and their consequences.

| Variable |

Existing Correlation |

Before |

After |

Consequences |

City Knowledge

|

Strong Positive |

Previous Knowledge |

Subsequent Knowledge |

Greater Utilization |

Everyday Life Perception

|

Low Positive |

Previous Perception |

Subsequent Perception |

Significant Change |

Invisible City Information

|

Low Positive |

Previous Perception |

Subsequent Perception |

Significant Influence |

Cultural Diversity Perception

|

Moderate Positive |

Previous Perception |

Subsequent Perception |

Perception Adjustment |

Institutional Transformation Action

|

Moderate Positive |

Previous Awareness |

Subsequent Commitment |

Commitment Increase |

Personal Transformation Action

|

Moderate Positive |

Previous Commitment |

Subsequent Commitment |

Critical Reflection |

Citizen Participation

|

Low Positive |

Previous Participation |

Importance Perception |

Increased Valuation |

Institutional Actions Commitment

|

Moderate Positive |

Previous Commitment |

Subsequent Commitment |

Moderate Evolution |

Personal Actions Commitment

|

Moderate Positive |

Previous Commitment |

Subsequent Commitment |

Moderate Increase |

General Knowledge

|

Not significant |

Previous Knowledge |

Knowledge Change |

Uniform Impact |

| Creativity and Critical Thinking Level |

Low Positive |

Previous Level |

Subsequent Level |

Potential Influence |

Table 12.

Summary of Regressions on knowledge, before and after the project, and their consequences.

Table 12.

Summary of Regressions on knowledge, before and after the project, and their consequences.

| # |

Analyzed Variable |

R squared |

P-value |

Brief Conclusions |

| 1 |

Change in historical and cultural knowledge

|

4.3% |

0.067 |

Weak and not significant correlation |

| 2 |

Relationship knowledge before-after

|

46.3% |

<0.001 |

Strong and significant relations |

| 3 |

Perception of everyday life |

0.4% |

0.318 |

Weak and not significant negative correlation

|

| 4 |

Change in perception of everyday life

|

0.1% |

0.428 |

Weak and not significant relationship |

| 5 |

Perception of the ‘invisible city’

|

1.4% |

0.397 |

Weak and not significant relationship

|

| 6 |

Perception of cultural diversity

|

2.2% |

0.289 |

Weak and not significant relationship

|

| 7 |

Perception of institutional actions

|

8.4% |

Significant |

Moderate and significant relationship |

| 8 |

Personal commitment to actions

|

13.3% |

Significant |

Moderate and significant relationship |

| 9 |

Civic participation |

3.9% |

0.075 |

Weak positive relationship

|

| 10 |

Change in personal commitment

|

7.8% |

Significant |

Moderate and significant relationship |

| 11 |

General knowledge |

35% |

<0.001 |

Strong and significant relationship

|

| 12 |

Creativity and critical thinking |

6.7% |

0.059 |

Moderate relationship, marginal |