1. Introduction

The relationship between people and their pets has been a significant societal aspect for centuries. Initially centered on nurturing, this relationship has evolved into one characterized by companionship and affection [

1,

2]. Brazil is renowned for its rich cultural heritage, encompassing diverse traditions and customs that vary expressively from region to region. Despite this variability of cultures, there is a unifying thread that runs through Brazilian society—the profound bond between pet owners and their animals. Whether it's with dogs, cats, or other pets, this relationship is universally valued and cherished across the nation.

According to IPB (2022) [

3], over 150 million Brazilians relate with their pets in loving and affectionate ways. This interaction transcends traditional limits, becoming integral to the social and emotional fabric of the Brazilian populace. Recognizing pets’ roles in their owners’ lives is vital for a deeper understanding of the intimacy of these relationships [

4].

Cohabitating with animals not only enhances human health but also promotes psychological well-being and extends longevity, this idea has been called the “pet effect” [

5]. A commonly utilized theoretical framework to elucidate the positive impacts of human-animal companionship is the Attachment Theory, positing that humans inherently possess a need for attachment or a sense of belonging to someone [

6].

Research indicates that individuals with a profound attachment to their pets may perceive minimal distinctions between interactions with humans and animals. The link between pet ownership and the provision of social support holds special significance for older individuals who may be single, divorced, remarried people, and people without children present, as they often exhibit higher levels of attachment to pets and also most likely to anthropomorphize them [

7]. This association becomes crucial, especially when considering previous findings indicating that pets can mitigate the adverse effects of lacking human social support [

8].

Given this context, this study sought to adapt the cat-owner/dog-owner relationship scales for measuring affectivity in pet-owner relationships. Howell et al. (2017) [

9] initially proposed these scales for cats, with adaptations for dogs by Riggio et al. (2021) [

4]. The Pet-Owner Relationship Scale (PORS) will be modified for both dog and cat owners in Brazil, which is in line with the global effort to recognize and quantify the significance of pets, particularly dogs and cats, for individuals’ mental and emotional health.

Pets provide companionship and emotional support, invaluable for people living whether individuals are living alone or coping with occupational illnesses [

10], owning pets, such as dogs and cats, indirectly promotes physical activity through activities such as daily walks, grooming, and veterinarian visits. These interactions contribute significantly to the physical and mental well-being of their owners. Research has consistently shown that petting a dog or a cat can lower stress levels and blood pressure, promoting relaxation and overall well-being [

11]. Moreover, dogs and cats play a crucial role in enhancing public health and population well-being by fostering social interactions and strengthening bonds between individuals, as well as between animals and people [

12]. Since cats are one of the most commonly owned pets throughout Western societies, understanding the qualities of cat-owner interactions, perceived emotional closeness, and perceived costs that correspond to a positive cat-owner relationship could improve outcomes for both cat and owner. Insights gleaned from such research could inform tailored interventions and support mechanisms, ultimately fostering healthier and more fulfilling bonds between cats and their owners

This article details the process of cross-culturally adapting the scales proposed by Howell et al. (2017) [

9] for cats and Riggio et al. (2021) [

4] for dogs to the Brazilian context. The questionnaire has been translated into Swedish [

13]; Spanish [

14]; German [

15]; Danish [

16]; and Dutch [

17]. In addition to Howell scale, it is known that other researchers used similar scales, for example, Lexington Attachment to Pets (LAPS), original scale [

18]; Mexican [

19]; Germany [

20]; and Brazil [

21].

By employing a comprehensive and culturally sensitive method, this study aims to provide a reliable scale for researchers, animal health professionals, and pet owners, enhancing the understanding of the pet-owner relationship’s dynamics and depth in Brazil. This study’s significance lies in the growing number of pet owners globally and the diverse roles pets play in Brazilian households. Pets are companions for the lonely, integral family members for households with children and the elderly, and sources of emotional support, promoting mental and physical health and enriching their owners’ daily lives [

22]. Moreover, dogs and cats play a crucial role in enhancing public health and population well-being by fostering social interactions and strengthening bonds between individuals, as well as between animals and people. These questionnaires will be completed by pet owners, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of the human-animal relationship. Hence, this research seeks to pave the way for future studies and interventions that benefit both owners and pets, underscoring the importance of this relationship in public health and social well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

This research employed a descriptive, comparative cross-sectional design with a quantitative approach. The study gathered data from a diverse cohort of pet owners spanning various professions and geographic regions in Brazil, including students, educators, healthcare professionals, law enforcement officers, civil servants, and workers from other sectors. Each participant had a distinct relationship with their pet.

Data was collected using online questionnaires using Google Forms and disseminated between September and November 2023 via social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp. Participation was contingent upon informed consent obtained after a thorough briefing on the study’s objectives. This research was conducted in strict adherence to ethical guidelines governing human subject research and secured approval from the Ethics Committee (CAAE no. 44261821.8.0000.5346, opinion no. 4.606.946).

2.1. Instrument

The scale adaptation for this study involved a panel of five esteemed animal health experts. These professionals evaluated and subsequently tailored the indicators to align with the Portuguese language and the context of dog and cat ownership. The original scale, conceptualized by Howell et al. (2017) [

9], comprises 3 (three) key dimensions and 29 (twenty-nine) indicators:

Perceived cost (PC), encompassing 9 (nine) indicators, gauges the owner’s perceived financial burden associated with pet ownership.

Perceived emotional closeness (PEC), with 11 (eleven) indicators, delves into the depth of the emotional bond between the pet owner and their animal, a critical factor in the overall quality of the relationship.

Pet-Owner Interactions (POI), featuring 9 (nine) indicators, quantitatively assesses the day-to-day interactions between the pet and its owner, including activities like play, grooming, and providing companionship. This dimension offers invaluable insights into the practical nuances of pet-owner relationships. The scale, refined through rigorous statistical analysis, is presented in the appendix.

2.2. Analysis of the Measurement and Conceptual Models

This study utilized the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 26.0) to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model derived from the original framework. The conceptual model underwent a thorough examination, leveraging the principal fit indicators common in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as noted by Shrestha (2021) [

23]. Additionally, the model’s applicability was assessed using SmartPLS software (version 4.1.0.0), employing covariance-based structural equation modeling as outlined by Ringle et al. (2022) [

24].

Step-by-step structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) to cross-culturally validate a scale: 1) metric invariance and reliability and validity assessment (

Table 2 and

Table 3); 2) residual invariance (

Figure 1 and

Table 4); and 3) report the results of hypothesis testing (

Table 5); 4) compare latent means to explore cultural differences (

Table 6); and 5) discuss the implications of cultural differences or similarities found in the study [

25].

2.3. Comparative Analyses

The Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was employed to discern and compare the behavioral patterns across different pet owner groups. This test was instrumental in identifying any notable disparities among the groups. Furthermore, a multigroup analysis was conducted to determine the model’s invariance and consistency across varied owner demographics.

2.4. Background of the Hypotheses

To elucidate the potential positive or negative relationships within the model’s dimensions, the following hypotheses were established to provide context.

We initially posited that the relationship between Perceived Cost and Emotional Closeness is inversely proportional. Perceived Cost, encompassing financial, time, physical, and emotional investments, negatively impacts an owner’s emotional closeness toward their pet. This could stem from the burdens of high costs, potentially leading to feelings of overload or stress, thereby affecting the owner’s emotional connection with the pet [

26].

Hypothesis 1: Perceived Cost is negatively related to Perceived Emotional Closeness.

There is a suggested negative correlation between Perceived Cost and Pet-Owner Interactions. Higher Perceived Costs associated with pet care are believed to result in less frequent or lower-quality interactions between the owner and the pet. This may be because owners who perceive higher costs may feel less inclined or able to engage frequently or positively with their pets [

27,

28,

29].

Hypothesis 2: Perceived Cost is negatively related to Pet-Owner Interactions.

Conversely, a positive relationship is anticipated between Perceived Emotional Closeness and Pet-Owner Interactions. It is assumed that the stronger the emotional bond an owner feels towards their pet, the more frequent and meaningful their interactions will be. A robust emotional connection typically fosters a greater desire to spend time with the pet, enhancing the quality and frequency of interactions for both the owner and the pet [

30,

31,

32].

Hypothesis 3: Perceived Emotional Closeness is related to Pet-Owner Interactions.

The study further posits that Perceived Emotional Closeness may act as a mediator between Perceived Cost and Pet-Owner Interactions. Even in the presence of high Perceived Costs, a strong emotional bond can mitigate these costs, leading to sustained or increased interaction with the pet. This suggests that pet owners who share a deeper emotional connection with their pets may be more resilient to the challenges associated with pet care [

26,

33,

34].

Hypothesis 4: Perceived Emotional Closeness mediates the relationship between Perceived Cost and Pet-Owner Interactions.

2.5. Profile

The study recruited 234 pet owners through convenience sampling. Eligibility criteria included being over 18 years old and owning a pet. As listed in

Table 1, the demographic breakdown of survey participants was as follows: 76.1% (n = 178) were female, 34.2% (n = 80) aged 18–30 years, 53.8% (n = 126) were married or in a long-term relationship, 38.5% (n = 90) had at least two household members, 48.3% (n = 113) held or were pursuing graduate degrees, and 82.1% (n = 192) resided in the southern region of Brazil. Most respondents (51.7%, n = 121) lived exclusively with dogs, 27.8% (n = 65) with both dogs and cats, and 20.5% (n = 48) solely with cats. Among dog-only households, 28.2% had only one dog, while 14.1% of cat-only households had a single cat. In households with both dogs and cats, a higher prevalence (12.8%) of having four or more pets was noted.

3. Results

The initial step involved conducting a CFA to validate the scale’s dimensional structures. This analysis verified which indicators effectively measured the dimensions, thus confirming the content and construct validity of the model based on participant responses. When the varimax rotation technique was applied, indicators with commonalities (

h2) below 0.6 were excluded. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure for all three dimensions surpassed 0.7, suggesting suitability for further analysis [

35].

Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) were assessed. These metrics aligned with standards set by Hair et al. (2017) [

20] (0.65 < θ < 0.95 and AVE > 0.5), indicating a consistent relationship between dimensions and indicators and demonstrating the model’s good convergent validity (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Dimensions, indicators, commonalities, cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted.

Table 2.

Dimensions, indicators, commonalities, cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted.

| Dimensions/indicators* |

h2

|

KMO |

θ(CA) |

θ(CR) |

AVE |

| Perceived Cost (PC) |

|

0.898 |

0.666 |

0.670 |

0.531 |

| PC02 |

0.640 |

|

|

|

|

| PC03 |

0.656 |

|

|

|

|

| PC04 |

0.780 |

|

|

|

|

| PC05 |

0.755 |

|

|

|

|

| PC06 |

0.610 |

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Emotional Closeness (PEC) |

|

0.765 |

0.820 |

0.824 |

0.586 |

| PEC01 |

0.694 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC02 |

0.661 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC03 |

0.718 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC06 |

0.831 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC07 |

0.860 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC08 |

0.823 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC09 |

0.756 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC10 |

0.893 |

|

|

|

|

| PEC11 |

0.624 |

|

|

|

|

| Pet-Owner Interactions (POI) |

|

0.802 |

0.880 |

0.886 |

0.587 |

| POI01 |

0.769 |

|

|

|

|

| POI02 |

0.718 |

|

|

|

|

| POI03i |

0.809 |

|

|

|

|

| POI04i |

0.692 |

|

|

|

|

| POI05i |

0.698 |

|

|

|

|

| POI06i |

0.844 |

|

|

|

|

For discriminant validity assessment, the Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) were utilized. Pearson's correlation analysis revealed that the square root of the lowest AVE (0.729) exceeded the highest correlation between dimensions (PEC vs. POI = 0.566), positioned below the main diagonal [

36]. Above the main diagonal, HTMT values were below 0.9 [

37]. These findings indicate that the model satisfactorily met the measurement validation criteria.

Table 3.

Fornell-Larcker and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio.

Table 3.

Fornell-Larcker and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio.

| Dimensions |

|

Pearson’s correlation matrix |

| PC |

POI |

PEC |

| PC |

0.729 |

1.000 |

|

|

| POI |

0.766 |

-0.342 |

1.000 |

|

| PEC |

0.766 |

-0.417 |

0.566 |

1.000 |

| |

HTMT |

| POI |

0.443 |

|

|

| PEC |

0.517 |

0.636 |

|

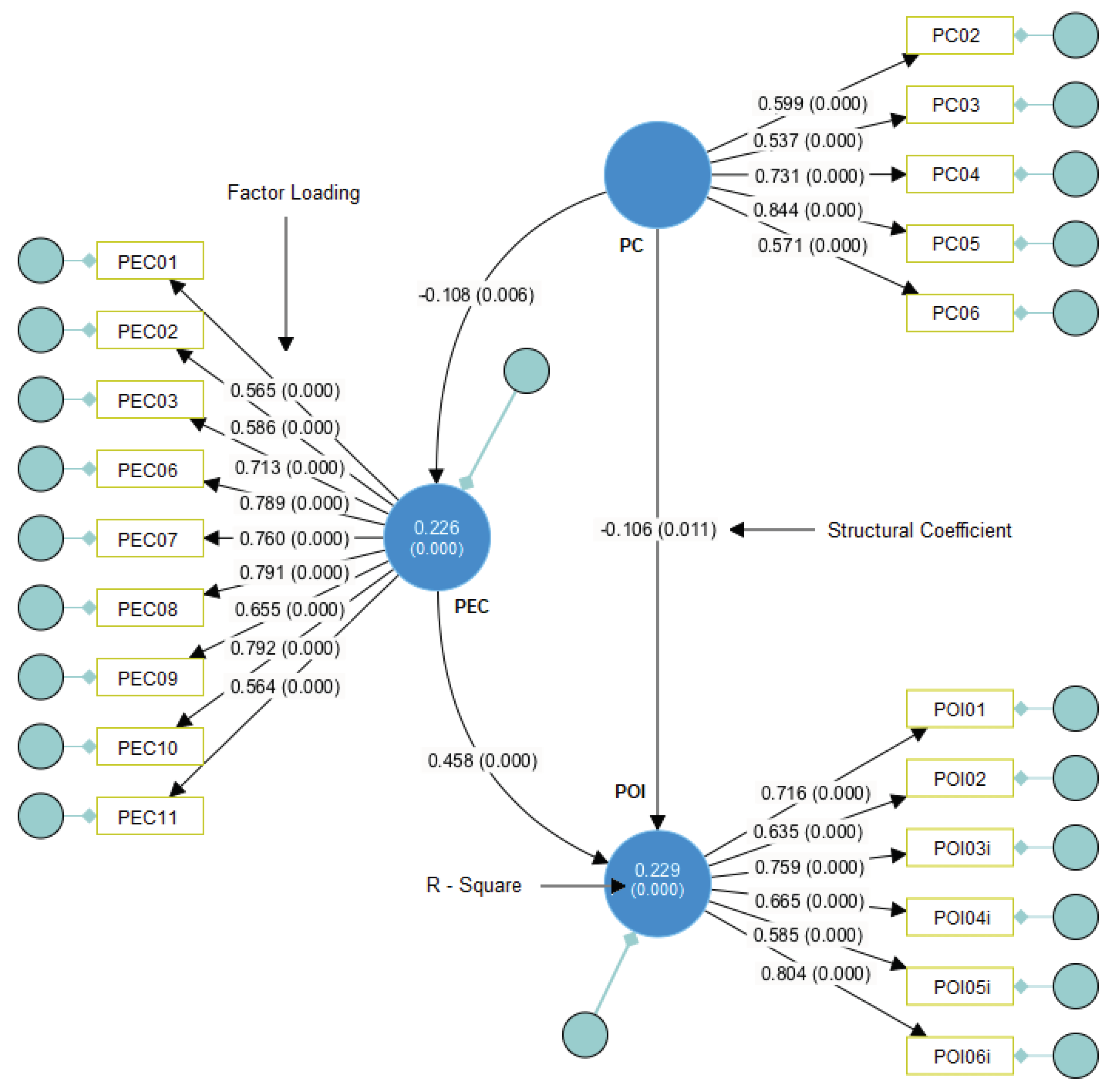

Figure 1 presents the structural relationships between the model’s dimensions, while

Table 4 details the model’s fit quality.

In the arrows linking the dimension (circle) with the indicators (rectangles), factorial loads are presented, which statistically should contain p < 0.05, in parentheses, meaning they are significant for the model. Conversely, linking one dimension to another presents structural coefficients and their significances; hypotheses will be confirmed when p < 0.05. Within predictive dimensions, explanation coefficients are presented along with their respective significances.

The results indicate a robust fit, evidenced by the chi-square test (χ² = 414.71), degrees of freedom (df = 167), chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df = 2.48), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.090), comparative fit index (CFI = 0.925), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = 0.046) [

37] (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Test of adequacy of the proposed model.

Table 4.

Test of adequacy of the proposed model.

| Models |

χ2

|

df |

χ2/df |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

GFI |

CFI |

NFI |

AGFI |

| Acceptable fit |

--- |

--- |

< 3 |

< 0.10 |

< 0.050 |

> 0.90 |

> 0.90 |

> 0.90 |

> 0.90 |

| Structural model |

414.71 |

167.00 |

2.48 |

0.09 |

0.046 |

0.96 |

0.92 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

Table 5 validates the proposed hypotheses. It confirms a significant inverse relationship between Perceived Cost and Perceived Emotional Closeness (H1) and between Perceived Cost and Pet-Owner Interaction (H2). Hypothesis H3 delineates the positive correlation between Perceived Emotional Closeness and Pet-Owner Interaction. Hypothesis H4 posits that Perceived Emotional Closeness mediates the relationship between Perceived Cost and Pet-Owner Interaction.

Table 5.

Analysis of structural coefficients.

Table 5.

Analysis of structural coefficients.

| Hypotheses |

Direct relationships |

β |

sd |

t-statistic (β/sd) |

p |

| H1 |

PC → PEC |

-0.108 |

0.047 |

2.298 |

0.006 |

| H2 |

PC → POI |

-0.106 |

0.043 |

2.010 |

0.011 |

| H3 |

PEC → POI |

0.442 |

0.024 |

3.564 |

0.000 |

| |

Indirect relationship (mediation) |

|

|

|

|

| H4 |

PC → PEC → POI |

0.099 |

0.034 |

2.944 |

0.001 |

Table 6 shows that for the three dimensions there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) between the types of owners, so it can be said that the indicators behave uniformly and homogeneously between the groups.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of dimensions between types of owners.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of dimensions between types of owners.

| Dimensions |

Dogs (n = 121) |

Cats (n = 48) |

Dogs and cats (n = 65) |

KW test |

| PC |

2.5 (0.76) |

2.5 (0.75) |

2.6 (0.72) |

0.585 |

| PEC |

4.1 (0.82) |

4.1 (0.72) |

3.9 (0.88) |

0.080 |

| POI |

4.6 (0.74) |

4.8 (0.66) |

4.7 (0.52) |

0.237 |

Table 7 shows that there were no significant differences between the structural coefficients (β) when comparing the groups two by two. This invariance ensures that the construct was reliably and consistently measured, regardless of cultural variations or different types of pets.

Table 7.

Structural and comparative analyses.

Table 7.

Structural and comparative analyses.

| Hypotheses |

Relationships (dogs) |

β |

sd |

t-statistic (β/sd) |

p |

| H1c |

PC → PEC |

-0.176 |

0.075 |

2.352 |

0.001 |

| H2c |

PC → POI |

-0.331 |

0.077 |

4.303 |

0.000 |

| H3c |

PEC → POI |

0.550 |

0.073 |

7.572 |

0.000 |

| H4c |

PC → PEC → POI |

0.125 |

0.023 |

5.369 |

0.000 |

| |

Relationships (cats) |

|

|

|

|

| H1g |

PC → PEC |

-0.306 |

0.082 |

3.719 |

0.000 |

| H2g |

PC → POI |

-0.380 |

0.109 |

3.481 |

0.001 |

| H3g |

PEC → POI |

0.275 |

0.120 |

2.287 |

0.002 |

| H4g |

PC → PEC → POI |

0.116 |

0.021 |

5.525 |

0.000 |

| Relationships (both = dogs and cats) |

|

|

|

| H1a |

PC → PEC |

-0.116 |

0.027 |

4.333 |

0.000 |

| H2a |

PC → POI |

-0.233 |

0.115 |

2.021 |

0.001 |

| H3a |

PEC → POI |

0.403 |

0.124 |

3.275 |

0.000 |

| H4a |

PC → PEC → POI |

0.127 |

0.026 |

4.793 |

0.000 |

| |

Difference = dogs - cats |

(β1 - β2) |

sd |

t-statistic |

p |

| H1cg |

PC → PEC |

0.130 |

--- |

1.265 |

0.208 |

| H2cg |

PC → POI |

0.049 |

--- |

0.172 |

0.863 |

| H3cg |

PEC → POI |

0.275 |

--- |

1.614 |

0.108 |

| H4cg |

PC → PEC → POI |

0.009 |

--- |

1.201 |

0.231 |

| |

Difference = dogs - both |

|

|

|

|

| H1ca |

PC → PEC |

-0.060 |

--- |

0.182 |

0.855 |

| H2ca |

PC → POI |

-0.098 |

--- |

0.367 |

0.714 |

| H3ca |

PEC → POI |

0.147 |

--- |

0.735 |

0.463 |

| H4ca |

PC → PEC → POI |

-0.002 |

--- |

0.025 |

0.980 |

| |

Difference = cats - both |

|

|

|

|

| H1ga |

PC → PEC |

-0.190 |

--- |

0.526 |

0.600 |

| H2ga |

PC → POI |

-0.147 |

--- |

0.730 |

0.467 |

| H3ga |

PEC → POI |

-0.128 |

--- |

0.395 |

0.694 |

| H4ga |

PC → PEC → POI |

-0.011 |

--- |

0.125 |

0.736 |

4. Discussion

A CFA was conducted using the scale of Howell et al. (2017) [

9], which originally included three dimensions and 29 indicators. Post analysis, the scale was refined to 20 indicators, distributed as 5 for PC, 9 for PEC, and 6 for POI.

Table 5 and

Table 7 support the hypotheses in the general context and across different pet owners. The lack of significant differences in beta values among pet owner groups denotes the scale’s invariance. The validation of Hypotheses 1 and 2 indicates an inverse relationship of PC with both PEC and POI. This suggests that the burdens of cost may impede the development of a strong emotional bond and active engagement with pets, a notion corroborated by several studies [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Understanding these dynamics is key to enhancing the well-being of pets and their owners, potentially informing strategies to improve their relationship. The confirmation of Hypothesis 3, which posits a positive relationship between PEC and POI, underscores the significance of emotional bonds in human-animal relationships. It suggests that stronger emotional connections lead to more frequent and higher-quality interactions, a conclusion supported by various research findings [

30,

31,

32]. From both ethological and psychological viewpoints, these findings highlight affection as a crucial factor in fostering positive human-animal interactions [

39,

40,

41].

Hypothesis 4 reveals that PEC acts as a mediator in the relationship between PC and pet interactions, implying that a strong emotional bond can alleviate the negative effects of high PC on interaction levels. These insights suggest that reinforcing emotional connections between owners and pets could be viable for maintaining or enhancing interactions, regardless of the associated costs. This positive mediation signifies that PEC intensifies the influence of PC on POI [

42]. Hence, a stronger emotional bond can effectively negate the deterring impact of PC on an owner’s willingness to engage with their pet [

26,

33,

34]. These validated hypotheses lay a solid scientific groundwork for a deeper understanding of the complexities inherent in pet-owner relationships, emphasizing the interplay between emotional and practical aspects. This knowledge serves as a foundation for future research, public policies, and practices aimed at enhancing the well-being of pets and their owners.

5. Conclusions

Based on the proposed objective and the scale’s validity, this study provides a deeply informed and scientifically grounded understanding of the relationship between pet owners and their pets. Adapting the scale proposed by Howell et al. (2017) [

9] and Riggio et al. (2021) [

4] for Brazilian dog and cat owners has proven to be psychometrically sound. The confirmatory factor analysis preserved many original indicators, thereby demonstrating the scale’s robustness.

As for the scale’s invariance, the absence of significant differences in coefficients among various types of pet owners (dogs vs. cats vs. dogs and cats) indicates that the scale is consistent across these groups in the Brazilian context, where a wide and culturally significant variety of pets is present. This suggests that the scale is reliable and valid for measuring constructs related to the pet-owner relationship in Brazil, irrespective of the type of pet. It is important to highlight that specific cultural and socioeconomic factors in Brazil may influence this relationship, underscoring the need for a contextualized analysis to ensure the accuracy and applicability of the results.

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for society and public health administration in devising practical and effective strategies to promote the well-being of both pets and their owners. By comprehending the intricate dynamics of pet-owner relationships, administrators can implement targeted interventions aimed at strengthening the emotional connection between them. These initiatives may include establishing pet-friendly policies, providing access to affordable veterinary care, promoting responsible pet ownership, and supporting mental health initiatives.

Administrations can allocate resources for mental health support services tailored to pet owners experiencing emotional distress or facing difficulties in their relationship with their pets. This includes providing access to counseling, support groups, and stress management programs tailored to the unique challenges of pet ownership.By incorporating these evidence-based strategies into public health policies and initiatives, administrations can effectively address the complex interplay between pet ownership and human well-being, ultimately fostering healthier and more resilient communities.

As limitations, the results of this study may not be generalizable to all pet-owner groups due to reliance on a convenience sample. Additionally, the accuracy of psychometric scales, particularly when adapted to different cultures or populations, may vary. Nevertheless, the scale demonstrated evidence of validity within the Brazilian context, reinforcing its applicability and relevance.

As a suggestion for future research, it is recommended to explore how pets’ behavior influences the owner-pet relationship. Integrating comprehensive behavioral assessments of pets could provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of this relationship. By examining various aspects of pets' behavior, such as temperament, socialization, and responsiveness to training, researchers can better understand how these factors impact the emotional closeness between owners and pets, as well as perceived costs associated with pet ownership.

Furthermore, investigating how pets' behavior evolves over time and how it interacts with owners' behavior and characteristics could offer a deeper understanding of the ongoing dynamics within the owner-pet relationship. For instance, longitudinal studies tracking changes in pets' behavior and their corresponding effects on owner satisfaction and attachment could shed light on the long-term implications of pet behavior on the strength and quality of the relationship.

Moreover, considering the role of environmental factors, such as living arrangements, access to outdoor spaces, and interaction with other pets or humans, in shaping pets' behavior and its impact on the relationship could provide additional insights. Understanding how these external influences intersect with pets' behavior and their owners' perceptions can contribute to the development of more targeted interventions and support strategies to enhance the well-being of both pets and their owners.

In summary, future research endeavors should aim to delve deeper into the intricate interplay between pets' behavior and the owner-pet relationship. By adopting a multidimensional approach that considers various factors and contexts, researchers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of how pets' behavior influences relationship dynamics and identify effective strategies to foster stronger and more fulfilling bonds between owners and their beloved companions

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.D.L., E.G.L., M.P.L., D.P. and J.V.S.; methodology, L.F.D.L., D.P., R.A.S. and T.R.L.; software, L.F.D.L.; validation, L.F.D.L., M.P.L., D.P. and J.V.S.; formal analysis, L.F.D.L., D.P. and M.P.L.; investigation, L.F.D.L., E.G.L., D.P., R.A.S. and T.R.L.; data curation, L.F.D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.D.L., E.G.L., M.P.L.; D.P.; writing—review and editing, R.A.S., T.R.L. and J.V.S.; visualization, L.F.D.L.; supervision, L.F.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee) of the Federal University of Santa Maria (CAAE no. 44261821.8.0000.5346, opinion no. 4.606.946).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Tiffani J. Howell for granting us permission to use the scale. This study was supported by the following Brazilian research agencies: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do RS (FAPERGS) and Atlas Assessoria Linguística for language editing. We would also like to thank Atlas Assessoria Linguística for language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The questionnaire applied to Brazilian pet-owners. (English and Portuguese for the purpose of this article).

Table A1.

The questionnaire applied to Brazilian pet-owners. (English and Portuguese for the purpose of this article).

| |

Escala de Relacionamento Pet-Tutor (ERPT)

PEP = Proximidade Emocional Percebida (Perceived Emotional Closeness - PEC)

CP = Custo Percebido (Perceived Cost - PC)

IPT = Interação Pet-Tutor (Pet-Owner Interactions - POI) |

|

| Item |

Questions |

Variable |

| 1 |

Meu PET me dá motivo para me levantar de manhã.

(My pet gives me a reason to get up in the morning) |

PEP01 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 2 |

Há aspectos importantes de ter um PET que eu não goste.

There are important aspects of having a pet that I do not like. |

CP02 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 3 |

Com que frequência você beija seu PET?

How often do you kiss your pet?

(1) Nunca (2) Uma vez por mês (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (5) Pelo menos uma vez por dia

|

PEP02 |

| (1) Never (2) Once a month (3) Once a week (4) Once every 3 days (5) At least once a day |

| 4 |

Eu gostaria que meu PET e eu nunca tivéssemos que estar separados.

I wish my pet and I never had to be apart. |

PEP03 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 5 |

Meu PET faz muita bagunça.

My pet makes a lot of mess.

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

|

CP03 |

| (1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 6 |

Com que frequência você brinca com seu PET?

How often do you play with your pet? |

IPT01 |

(1) Nunca (2) Uma vez por mês (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (5) Pelo menos uma vez por dia

(1) Never (2) Once a month (3) Once a week (4) Once every 3 days (5) At least once a day |

| 7 |

Incomoda-me que meu PET me impeça de fazer coisas que eu gostava antes de adotá-lo.

It bothers me that my pet prevents me from doing things I enjoyed before I adopted it. |

CP04 |

| (1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 8 |

Com que frequência você passa o tempo observando seu PET?

How often do you spend time watching your pet? |

IPT02 |

(1) Nunca (2) Uma vez por mês (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (5) Pelo menos uma vez por dia

(1) Never (2) Once a month (3) Once a week (4) Once every 3 days (5) At least once a day |

| 9 |

É desagradável que às vezes eu tenha que mudar meus planos por causa do meu PET.

I find it unpleasant that sometimes I have to change my plans because of my pet. |

CP05 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 10 |

Meu PET gera custos altos para meu orçamento.

My pet adds significant expenses to my budget. |

CP06 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 11 |

Com que frequência você conversa com seu PET?

How often do you talk to your pet? |

IPT03i* |

(1) Pelo menos uma vez por dia (2) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez por mês (5) Nunca

(1) At least once a day (2) Once every 3 days (3) Once a week (4) Once a month (5) Never |

| 12 |

Gostaria de ter meu PET perto de mim o tempo todo.

I want to have my pet near me all the time. |

PEP06 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 13 |

Se as pessoas me deixassem, meu PET sempre estaria comigo.

If people left me, my pet would always be with me. |

PEP07 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 14 |

Meu PET me ajuda a passar por momentos difíceis.

My pet helps me through difficult times. |

PEP08 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 15 |

Com que frequência você abraça seu PET?

How often do you hug your pet? |

IPT04i* |

(1) Pelo menos uma vez por dia (2) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez por mês (5) Nunca

(1) At least once a day (2) Once every 3 days (3) Once a week (4) Once a month (5) Never |

| 16 |

Meu PET me proporciona companhia constante.

My pet provides me with constant companionship. |

PEP09 |

(1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 17 |

Com que frequência você tem seu PET com você enquanto relaxa?

How often do you have your pet with you while you relax? |

IPT05i* |

(1) Pelo menos uma vez por dia (2) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez por mês (5) Nunca

(1) At least once a day (2) Once every 3 days (3) Once a week (4) Once a month (5) Never |

| 18 |

Meu PET está por perto sempre que preciso ser consolado.

My pet is always around whenever I need to be comforted. |

PEP10 |

1) Discordo totalmente (2) Discordo (3) Nem concordo nem discordo (4) Concordo (5) Concordo totalmente

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree |

| 19 |

Quão traumático você acha que será para você quando seu PET morrer?

How traumatic do you think it will be for you when your pet dies? |

PEP11 |

(1) Muito não traumático (2) Não traumático (3) Nem traumático nem não traumático (4) Traumático (5) Muito traumático

(1) Very non-traumatic (2) Non-traumatic (3) Neither (4) Traumatic (5) Very traumatic |

| 20 |

Com que frequência você acaricia seu PET?

How often do you pet your pet? |

IPT06i* |

(1) Pelo menos uma vez por dia (2) Uma vez a cada 3 dias (3) Uma vez por semana (4) Uma vez por mês (5) Nunca

(1) At least once a day (2) Once every 3 days (3) Once a week (4) Once a month (5) Never |

References

- Menache, S. Dogs and human beings: A story of friendship. Soc. Anim. 1998, 6, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Domestication and history of the cat. In The domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, 2nd ed.; 2000; pp. 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- IPB - Instituto Pet Brasil. Censo Pet IPB: com alta recorde de 6% em um ano, gatos lideram crescimento de animais de estimação no Brasil. 2022. Available online: https://institutopetbrasil.com/fique-pordentro/amor-pelos-animais-impulsiona-os-negocios-2-2/.

- Riggio, G.; Piotti, P.; Diverio, S.; Borrelli, C.; Di Iacovo, F.; Gazzano, A.; Howell, T.J.; Pirrone, F.; Mariti, C. The dog–owner relationship: Refinement and validation of the Italian C/DORS for dog owners and correlation with the LAPS. Animals 2021, 11, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K. Are pets a healthy pleasure? The influence of pets on blood pressure. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2003, 12, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds: II. Some principles of psychotherapy: The Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture (expanded version). Br J Psychiatry 1977, 130, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, A.; Bulcroft, K. Pets, families, and the life course. J Mar Fam 1988, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzler, B.; König, H.H.; Hajek, A. Pet ownership, loneliness, and social isolation: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2022, 57, 1935–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.J.; Bowen, J.; Fatjó, J.; Calvo, P.; Holloway, A.; Bennett, P.C. Development of the cat-owner relationship scale (CORS). Behav. Processes. 2017, 141, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foltin, S.; Glenk, L.M. Current Perspectives on the Challenges of Implementing Assistance Dogs in Human Mental Health Care. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.T.; Johnstone, S.J.; Römer, S.S.; Thomas, S. J. Psychophysiological mechanisms underlying the potential health benefits of human-dog interactions: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2022, 180, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L.; Clements, M.A.; Elliott, L.J.; Meehan, E.S.; Montgomery, C.J.; Williams, G. A. Quality of the human–animal bond and mental wellbeing during a COVID-19 lockdown. Anthrozoos 2022, 35, 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handlin, L.; Nilsson, A.; Ejdebäck, M.; Hydbring-Sandberg, E.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. Associations between the Psychological Characteristics of the Human–Dog Relationship and Oxytocin and Cortisol Levels. Anthrozoos 2012, 25, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Bowen, J.; Bulbena, A.; Tobeña, A.; Fatjó, J. Highly Educated Men Establish Strong Emotional Links with Their Dogs: A Study with Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS) in Committed Spanish Dog Owners. Plos One 2016, 11, e0168748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöberl, I.; Beetz, A.; Solomon, J.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Social factors influencing cortisol modulation in dogs during a strange situation procedure. J. Vet. Behav. 2015, 11, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.; Forkman, B. Dog and owner characteristics affecting the dog–owner relationship. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 20149, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houtert, E.A.; Endenburg, N.; Wijnker, J.J.; Rodenburg, T.B.; van Lith, H.A.; Vermetten, E. The translation and validation of the Dutch Monash dog–owner relationship scale (MDORS). Animals 2019, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington attachment to pets scale (LAPS). Anthrozoos 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.T.G.; Quezada Berumen, L. D. C.; Hernández, R. L. Psychometric properties of the lexington attachment to pets scale: Mexican version (LAPS-M). Anthrozoos 2014, 27, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, B.; Gansloßer, U.; Froböse, I. Attachment to Dogs and Cats in Germany: Translation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS) and Description of the Pet Owning Population in Germany. Hum. Anim. Interact. Bull. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, N.S.; Costa, D.B.; Reis Rodrigues, G.; Sessegolo, N.S.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Irigaray, T. Q. Adaptation and psychometric properties of Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale: Brazilian version (LAPS-B). J. Vet. Behav. 2023, 61, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Johnson, I.; Bamwine, P.; Light, M. The Pet Paradox: Uncovering the Role of Animal Companions During the Serious Health Events of People Experiencing Homelessness. Anthrozoos 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH: SmartPLS, 2022. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com.

- Collier, J. Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques; Routledge, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Maltby, J.; Mills, D.S. Potential Psychosocial Explanations for the Impact of Pet Ownership on Human Well-Being: Evaluating and Expanding Current Hypotheses. Hum. Anim. Interact. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.R. The dimensions of pet-owner loyalty and the relationship with communication, trust, commitment and perceived value. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkouri, A.; Graham, T.M.; O’Haire, M.E.; Purewal, R.; Westgarth, C. Dogs and the good life: a cross-sectional study of the association between the dog–owner relationship and owner mental wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 903647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipperman, B. The Influence of Economics on Decision-Making. Decis. Mak. Vet. Pract. 2023, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli, C.; Riggio, G.; Howell, T.J.; Piotti, P.; Diverio, S.; Albertini, M.; Mongillo, P.; Marinelli, L.; Baragli, P.; Di lacovo, F.P; Gazzano, A.; Pirrone, F.; Mariti, C. The Cat–Owner Relationship: Validation of the Italian C/DORS for Cat Owners and Correlation with the LAPS. Animals 2022, 3, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Almeida, M.; Gomes, C. The role of dogs in the relationship between telework and performance via affect: A moderated moderated mediation analysis. Animals 2022, 12, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somppi, S.; Törnqvist, H.; Koskela, A.; Vehkaoja, A.; Tiira, K.; Väätäjä, H.; Surakka, V.; Vainio, O.; Kujala, M. V. Dog–owner relationship, owner interpretations and dog personality are connected with the emotional reactivity of dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Haase, D.; Heiland, S.; Kabisch, N. Urban green space interaction and wellbeing–investigating the experience of international students in Berlin during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, L.S.; Stangl, B.; Morgan, N. Dog Guardians’ Subjective Well-Being During Times of Stress and Crisis: A Diary Study of Affect During COVID-19. People and Animals: Int. J. Res. Pract. 2023, 6, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: Los Angeles, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. , Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, X. Development of the growth mindset scale: Evidence of structural validity, measurement model, direct and indirect effects in Chinese samples. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1712–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, G.; Jensen, M. B.; Moe, R. O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L. J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; LongBein, J.; Bakken, M.; Veissier, I.; Aubert, A. Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rault, J.L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The power of a positive human–animal relationship for animal welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Dobos, P. What is a companion animal? An ethological approach based on Tinbergen’s four questions. Critical review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 106055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, N.; Weng, H. Y.; L. McV. Messam, L. Temporal patterns of owner-pet relationship, stress, and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the effect of pet ownership on mental health: A longitudinal survey. Plos One 2023, 18, e0284101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).