1. Introduction

Recorded as the most vicious compared to its predecessors, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) presented a worldwide medical emergency that swiftly altered dynamics within the healthcare system [

1,

2]. Computed tomography (CT) and projectional radiography’s invaluable roles in differential diagnosis, detection and follow up on COVID-19 complications resulted in the radiology department’s direct involvement with the challenges that the pandemic introduced or worsened [

3,

4]. Comprising heightened death rates, loss of income, overwhelmed healthcare facilities and frail health status of oneself or a family member, the consequences of COVID-19 were widespread and significant [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Globally, several radiology departments faced shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), staff shortages, increased workloads, ever-evolving imaging requirements and rapid adaptation to new protocols. Moreover, in other radiology departments including those within KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa, loss of income within the private sector, poor work-life balance, faulty equipment, and lack of managerial support exacerbated the challenges [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Studies conducted to measure coronavirus stress levels have shown a significant difference between pre COVID-19 and post COVID-19 levels; thereby, corroborating phenomenological findings reporting that COVID-19 and its sequels had a tremendous impact on healthcare workers’ mental well-being which has a prolonged history of occupational stress [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Considering the nature of health caregivers’ roles, the consequences of work-related stress cannot be overemphasised as incorrect radiological diagnosis, increased accidental or unintended radiation exposures, incorrect patient identification and increased medical litigations have been linked with poor mental wellbeing among radiology healthcare professionals [

10,

11].

While the lived experiences of some of the radiology caregivers during COVID-19 pandemic have been explored [

4,

5,

6,

7,

11], the specific coping mechanisms that were adopted by the eThekwini-based radiology caregivers to subsist the diverse challenges and consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic remain unknown. Comprehension of the employed coping strategies is paramount for not only recognising their resilience but also for informing future health crises’ preparedness and development of support systems tailored to the specific radiology caregivers’ needs and preference. Therefore, aligning with recorded recommendations following heightened coronavirus anxiety scale scores among South African radiographers [

9]. This also contributes towards South Africa’s mental health policy (MHP) of mental health promotion and prevention among all South Africans by 2030 [

12]. Moreover, this would potentially support radiology caregivers in attaining the World Health Organisation’s definition of mental wellbeing which is a state in which individuals can handle stress and work productively enough to contribute towards their communities [

13].

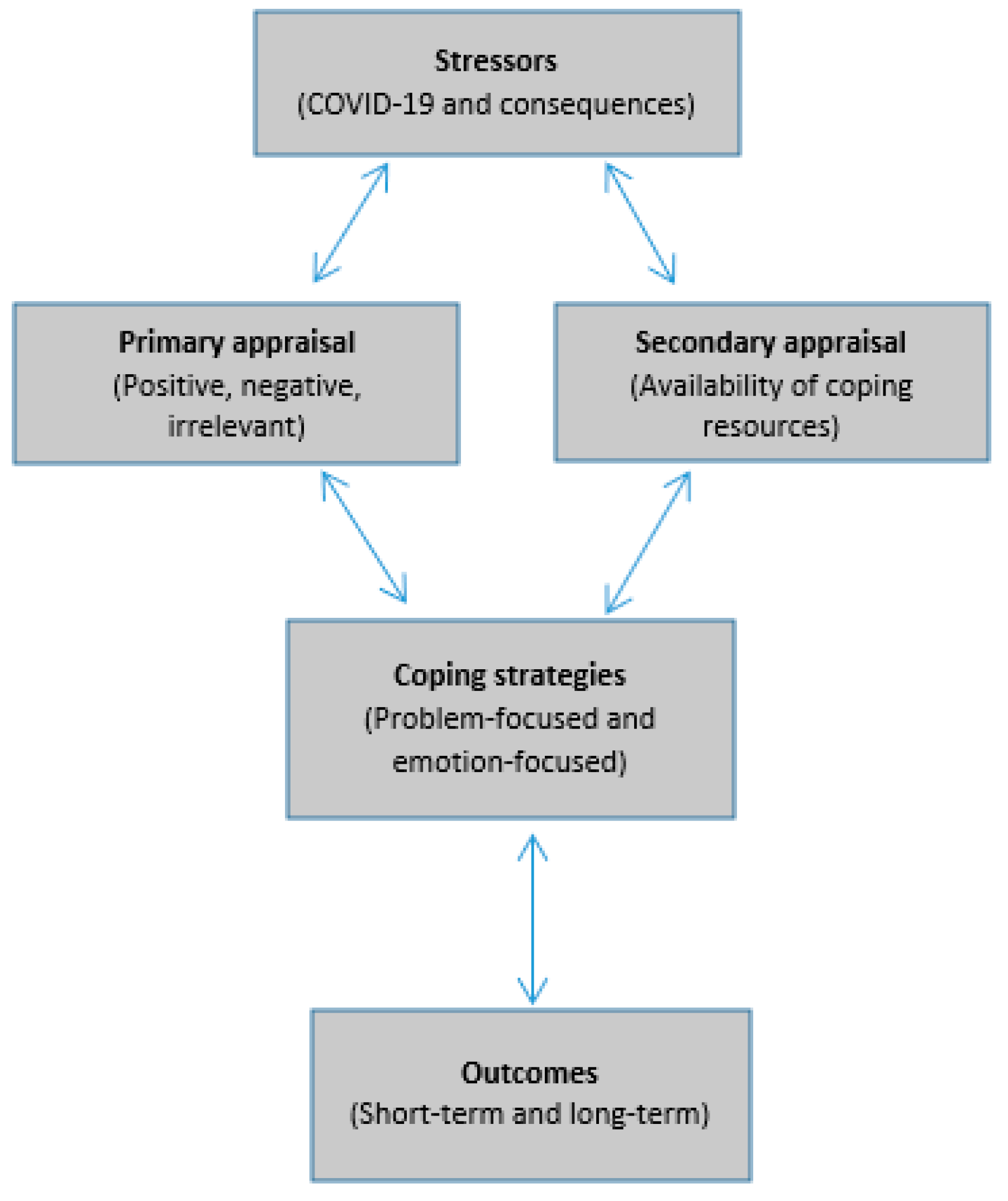

Towards this end, with the aim of exploring the coping strategies adopted by radiology caregivers within the eThekwini district of KZN, the study made use of the widely recognised transactional model of stress and coping (TMSC) (

Figure 1) to provide a solid theoretical basis. Developed to enable a better understanding of the processes underpinning stress and coping attempts, the TMSC has been incorporated in occupational stress and coping research studies exploring the lived experiences and coping mechanisms implemented by teaching professionals and patient carers [

14,

15,

16]. The TMSC views stress as a produce of a transaction between the affected individual and their environment through a series of appraisals, response, coping and reappraisal with COVID-19 and sequels as the environment or stressor, and radiology caregivers as the affected individuals in the current study (

Figure 1) [

14]. However, these processes are not the same for all individuals despite going through a similar experience as individuals’ perception of their experiences and consequences can result in the individuals reacting to the stressor differently. Furthermore, evaluation of available coping resources during secondary appraisal, awareness and perceived benefits of the intervention influences the coping strategies that individuals are likely to engage with [

14,

17]. The TMSC identifies emotion-focused and problem-focused as the two main coping strategies. While emotion-focused strategies aim to change the stressed individual’s response to the stressor without altering or eliminating the external stressor, problem-focused coping comprise problem-solving efforts to manage or eliminate the stressor [

14,

18]. Identified as self-destructive and maladaptive, dysfunctional coping is another category of coping which has been developed external to the TMSC [

18].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Methodology

To ensure methodological rigor, the nature of the study’s aim of sense making of the employed coping strategies found adopting a constructivist epistemological position and interpretivist theoretical stance with an inductive approach most suitable [

19]. In keeping with this, a qualitative interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) methodology was employed in a multi-case study context to allow the voice capture of all three frontline radiology caregiver professional categories within the department – nurses, radiographers and radiologists. IPA allowed critical assessment and interpretation of the participants’ adopted strategies through intense dialogues [

20].

2.2. Population and Sampling Process

The study population comprised South African Nursing Council (SANC) registered nurses, Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) registered radiologists and diagnostic radiographers working in both private and public radiology departments within the eThekwini district of KZN, South Africa. Participants had to have at least two years of work experience within their current roles to exclude extraneous variables influencing their choice of coping strategies. Moreover, students, registrars and community service staff were also excluded. For maximum inclusivity, all genders were included in the study. The heterogenous nature of the population called for the maximum variation purposive sampling method to ensure all three professions (radiologists, radiographers and nurses) and both work settings (private and public) were represented in the findings.

2.3. Data Collection Tool

The interview and focus group guides were formulated by interlinking the study’s aim with the concepts of the TMSC, as frameworks aid in ensuring the data collection tool is directed towards gathering the intended data. To support the semi-structured nature of the data collection process, the guides provided an outline of the focus areas but also accommodated flexibility to adapt the interview or focus group discussion (FGD) spontaneously by expanding on the points arising during the discussion. An open-ended question with probing questions allowed for a comprehensive exploration of the participants’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic – What strategies have you adopted to cope with the challenges and resultant stress during the COVID-19 pandemic? To ensure errors were addressed and that the tool was gathering the data as intended, the guides were pretested by the researcher among individuals who did not take part in the final data collection.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Ethical Considerations

Prior to data collection, ethical approval was sought from XXX (Ref: XXX) [Masked for blind review] and gatekeeper permissions were obtained from the relevant institution, district and provincial health departments. Participants were issued a letter of information and invited to participate via email or in person during departmental meetings. The participants were advised on the voluntary nature of the study and that they had the autonomy to withdraw from the study at any point without any consequences. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before data collection. Considering the importance of ensuring that participants were comfortable and safe as there were infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols at the time, participants were given an opportunity to choose their preferred platform of conducting the interview or FGD as well as their preferable time. Therefore, data were generated either telephonically or online depending on the participant’s preference. Data were collected through one-on-one interviews and two FGDs between May and September 2021. These were recorded upon the participants’ approval. Confidentiality was prioritised throughout the study by anonymising participants and keeping the data safe.

2.5. Data Analysis

Recorded data collection sessions were transcribed verbatim by an independent transcriber and checked by the interviewer and supervisors. To allow for a capture of each participant’s narrative of their adopted coping strategies and double hermeneutics, IPA was the preferred data analysis method [

20,

21]. This involved steps of in-depth engross in a single set of data before moving to the next case. Each transcript was read several times while noting any thoughts, semantic contents and language on the reflective log. Emergent superordinate themes were developed, and connections sought among them in relation to abstraction, subsumption, polarisation, contextualisation, numeration, and function. After which, the analyst moved on to the next transcript and eventually conducted a second-order analysis to construct a collective table of superordinate themes for the whole sample [

20,

22].

2.6. Trustworthiness

Rigor of the study and its findings were ensured throughout the study through adoption of the Trustworthiness framework. To warrant credibility of the findings, an interview schedule was developed, and the interview piloted to enhance the data collector’s interviewing and focus group facilitation skills [

23]. Furthermore, peer validation and cross-checking of data collection notes with recordings were conducted by the researcher and supervisors. A comprehensive audit trail of the research process and materials establishing dependability of the findings were kept. Investigator triangulation in the form of two data analysts and reflective journaling enabled confirmability of the study findings [

23,

24,

25]. The use of maximum variation purposive sampling addressed transferability of the findings by ensuring inclusion of the heterogenous population (radiologists, radiographers and nurses).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

The sample of 24 frontline radiology caregivers comprised – radiologists, radiographers and radiology nurses with 75% female. Participants were working in either private (33.3%) or public (66.7%) radiology departments with most of the participants within the 18-39 age ranges. Participant radiographers had several grade categories with the majority within Grade 1 and the least number occupying managerial positions. Work experiences within professional roles, were dominantly 6-10 years although a few had above 20 years.

3.2. Findings

Overall, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the eThekwini-district based frontline radiology caregivers exhibited high levels or resilience and adopted coping strategies that resulted in two superordinate themes, (1) Problem-focused, (2) Emotion-focused (

Table 2).

3.2.1. Superordinate Theme 1. Problem-Focused Coping

Problem-focused coping among frontline radiology careivers comprised three subordinates, namely: (1) adaptive behavioural coping, (2) occupation-focused coping (escape-avoidance), (3) solution-oriented. To cope with the challenges presenting within Radiology departments during the COVID-19 pandemic, some participants sort practical ways of resolving the problems. This included adaptive behavioural coping whereby radiology caregivers adjusted their practices and mindset.

“... we were practical in our approach and therefore even though there was shortage of PPE we were not short, because we worked around the issue.” (Radiographer, Participant 11).

To cope with physical challenges such as staff shortages, salary cuts and continuous exposure to the highly contagious virus, other participants took on a solution-oriented approach by formulating practical solutions for the unique challenges. This included modifying the roster to reduce the number of times that staff were scheduled to attend to COVID-19 patients.

“… eventually… I hardly did any more COVID-19 patients. I would scan them, but someone else would be the contact person…” (Radiographer, Participant 10).

Among themselves, some participants resorted to teamwork as a way of coping with the workload and physical strains of the job.

“While one is entering the details, the other radiographer has to position and another can take cassettes and process them…you will be helping each other to lift the patient…” (Radiographer, Participant 2).

Changes to the rotation were also considered tactical ways of minimising cross-infection among colleagues as this was another major challenge.

“We needed to design a shift where radiographers do not need to mix so as to minimise cases of cross infection among colleagues … They needed a shift where this group is working, the other group is not working so that we can still have another group to carry on and provide 24-hour service.” (Radiographer, Participant 2).

The radiologists also implemented new rosters for reporting staff to address the challenge of small workspaces that prohibited proper implementation of social distancing among staff.

“…we had to have a roster to limit the number of people in that small reporting room at a time…” (Radiologist, Participant 13).

Private-based radiology caregivers experienced abrupt major salary cuts and pause of work contracts thereby impacting staff shortages and financial distress. To cope, some participants had to use their savings and cancel any plans requiring financing.

“…my trip that I had booked was cancelled…all the money we had saved was what we used when we had a salary cut…” (Radiographer, Participant 10).

To cope with working within a highly infectious environment, participants strictly adhered to IPC protocols as a means of protecting themselves from contracting the virus within the workplace.

“I told the staff, 50% of your battle with COVID-19 is won by wearing the correct PPEs and by washing hands.” (Radiographer, Participant 11).

Other strategies comprised ensuring inclusion in decision-making of IPC protocols in radiology settings and vocalising the need for improvement of ventilation to mitigate the spread of the virus as some participants saw this as the best way forward to cope with the challenging COVID-19 situation.

“The ventilation system has not improved yet because they will need to install an extractor fan. So, we are hoping that that will help with the virus … the D-germ lights extracts the virus quicker…” (Radiographer, Participant 2).

Some participants, particularly radiographers who were continuously in close contact with COVID-19 patients, perceived occupation-focused coping (escape-avoidance) as the only way out. This included avoiding duties involving imaging of COVID-19 patients and the thought that changing careers would be the best solution.

“If maybe there is a COVID-19 patient coming down to the department for CT or x-rays, we would run away. We would not even want to come back…Perhaps one can move to a different field (career) where you will not be in contact with the patient.” (Radiographer, Participant 2).

Considering the severity and infectious rate of the virus, introduction of the COVID-19 vaccine brought hope for the staff to cope during these times as they took it as a practical solution for their own protection as they carried their duties during the pandemic.

“Yes, definitely I am no longer scared. Especially now that I am vaccinated also.” (Radiographer, Participant 7).

3.2.2. Superordinate Theme 2. Emotion-Focused Coping

Emotion-focused coping among frontline radiology caregivers comprised six subordinates, namely: (1) accepting professional responsibility and duties, (2) social coping, (3) appraisal-focused coping, (4) relaxation and physical efforts, (5) spiritual therapy, (6) psychological counselling. Most of the frontline radiology health caregivers turned to emotional-based strategies to cope with either mental related challenges or any other challenges they felt they did not have a physical solution for. The adopted emotion-focused coping strategies comprised accepting professional responsibility and duties through accepting the reality that their professional careers involved working with different types of patients under unfavourable conditions such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This helped keep staff motivated and develop resilience and endurance.

“I just think it is our job at the end of the day. So, we have to do it. And then you just pick yourself up and you motivate yourself to move forward and think that you know what, you need this, this is your job at the end of the day.” (Radiographer, Participant 3).

“I think maybe I accepted early, because we always work with people with tuberculosis (TB) we treat them like every other patient even those ones with COVID-19...” (Radiology nurse, Participant 18).

For some radiology health caregivers, colleagues and family provided consolation for mental health related challenges through social coping. This included spending time with family members, having a good laugh with colleagues or sharing their work experiences and challenges as co-workers.

“…. but now people talk about it, we do joke about it. We have our departmental WhatsApp group…Our interpersonal relationships within the department have helped to ease a bit of the anxiety.” (Radiologist, Participant 6).

“…we had to try and give ourselves emotional support as a group” (Radiology nurse, Participant 8).

“I just want to go clean up and soak my clothing and be with my family.” (Radiographer, Participant 11).

Other participants implemented appraisal-focused coping through accepting the situation, adapting mentally and building resilience.

“I knew mentally I was quite strong, that if you wipe up and if you sanitise, if you wear the correct PPEs and you follow protocols, then you will not be infected and, I think, that carried me through all the waves… people are so used to the presence of COVID-19.” (Radiographer, Participant 11).

Participants were aware of psychological counselling services provided by most institutions as well as the benefits of such sessions although most did not indicate making use of the services.

“We had psychological support at one point when the stress level was too high…It was a psychologist in the hospital.” (Radiologist, Participant 6).

Activities such as walks by the beach, journaling, exercising and reading, were some of the coping mechanisms adopted by participants to deal with mental related distress during the pandemic.

“I kept a journal from the beginning...“(Radiology nurse, Participant 8)

“… I feel that exercise has helped me. Other things that I enjoy is reading, it just helps me disconnect from what is occurring around me, in a positive way.” (Radiographer, Participant 12).

Several participants found solace in prayer and faith in God for guidance through the pandemic (spiritual therapy).

“…. what has kept me going is prayer and faith in God.” (Radiographer, Participant 4).

Notwithstanding the resentment resulting from salary cuts, private-based radiology caregivers treasured their management’s motivation and support which was in the form of recognition of efforts, provision of coping support and PPE, constant checking and cheering on of staff as well as circulation of motivational material and updates on COVID-19.

“Management giving us PPE and checking my vitals …also did make some small cheer me ups at work and they would buy us cake now and then. Just to encourage the staff or even we received emails to say thank you. They were very grateful that we put our lives at risk during COVID-19.” (Radiographer, Participant 10).

4. Discussion

The eThekwini-based frontline radiology caregivers demonstrated adaptability and professional resilience as fellow radiology caregivers globally [

5,

6,

7]. In keeping with TMSC and literature, they resorted to changing the situation (problem-based) and changing one’s relation to the situation (emotion-focused) as ways of coping and managing challenges and mental effects arising during the COVID-19 pandemic [

14,

18]. Radiology caregivers implemented problem-focused coping strategies such as adaptive behavioural coping, occupation-focused coping (escape-avoidance) and solutions to solve practical problems which were potential stressors. The ability of problem-based coping to address challenges head-on and prevent spiraling in the workplace provided more sustainable solutions which we either temporary or permanent. Implementation of primary interventions resonated with findings among Ghananian, Malaysian and Nigerian radiology and radiography personnel who resorted to work adaptations and job redesign as the most preferable coping strategies [

26,

27,

28]. Moreover, this also aligns with Oleaga’s COVID-19 recommendations for radiology departments and staff, to take lessons from it and adopt procedures to match with any potential future health crises [

29].

The redesigning of rosters to minimise repeated exposure to the virus and ensure continuous service delivery allowed radiology caregivers to have family support when not on duty, therefore aligning with findings in Pakistan [

30]. Overall, the introduction of the vaccine brought some relief that made the radiology caregivers feel more safer while conducting their duties. Similar to Shahid et al, solutions to staff shortages were beyond the radiology caregivers’ capability, therefore they relied on teamwork to cope with the increased workload [

30]. Teamwork is an imperative attribute within healthcare departments; hence, the participants’ practice was commendable. On the other hand, some radiology caregivers turned to maladaptive coping strategies which did not align with expected healthcare workers’ professional behaviours. This included avoiding duties that involved close contact with COVID-19 patients. To cope with salary cuts some staff used their savings and cancelled plans, which was understandable considering that most travels had been banned with the implemented lockdowns; however, use of savings was detrimental. Financial intervention or relief efforts by the employer would have been beneficial in demonstrating support for their staff, which according to Makanjee et al influences staff retention [

31].

Although problem-focused coping seeks to eliminate or manage the stressor [

14], it was not feasible for all the challenges due to external attributors beyond the individual’s control. Hence, radiology caregivers had to change their response to the stressors instead [

14,

32]. In this regard, radiology caregivers practised accepting professional responsibilities and duties, appraisal-focused coping, social coping, spiritual therapy, exercise, reading [

26,

28] and at times did not take any action at all. These secondary intervention strategies aligned with the TMSC, Cooper et al and findings among radiology and radiography staff globally [

14,

18,

26,

33,

34]. This coping method is considered a powerful choice and potentially aids in developing emotional resilience as reported among Gauteng-based radiographers [

5]. Radiographers in private practice found managerial support very beneficial therefore corroborating findings that perceive organisational support as a foster of positive working environments, staff retention and job performance among radiographers [

31].

Some radiology caregivers reported venting as a coping strategy. There are views of positive venting being beneficial in opposition to negative venting which is considered a dysfunctional intervention [

18]. Nevertheless, the current findings are not unique as radiology staff in some parts of the world reportedly adopted dysfunctional coping styles such as increased sedentary patterns, increased caffeine intake, self-distraction, increased screen time and alcohol to cope during the COVID-19 pandemic [

8,

28]. Although the radiology staff were aware of recommended tertiary interventions such as the psychological counselling services which were being offered within their institutions, none of the participants made use of the resources. This echoes findings in Ghana [

26].

The differences in adopted coping strategies could be attributed to different circumstances and individual preferences. Considering how volatile the situation was within their working environment during the pandemic, radiology staff adopted coping strategies with the potential for rapid outcomes; therefore, outcomes were mostly short-term [

14]. Considering that the study was not longitudinal, the possible long-term effects of their coping efforts are unknown at this point. In keeping with TMSC, the process was a loop as radiology caregivers repeatedly interacted with the stressors (COVID-19 and consequences) and experienced different COVID-19 waves with unique challenges, variances in availability of resources, therefore reappraising the outcome of their coping efforts from time to time [

14]. This resonates with other studies indicating increased effectiveness of regularly adapting coping mechanisms [

26,

28].

Despite the grounded benefits of the adapted methodology, the qualitative nature of the study which called for a limited sample size, prevents the generalisation of the current findings to a wider population. Nevertheless, consistent with the study’s aim, the chosen methodology has captured diverse accounts of the radiology caregivers’ lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, providing baseline information to aid departments in supporting staff presently and during any future health crises. Post-COVID-19 surveys are recommended to identify potential post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and identify the impact of the pandemic on current radiology and radiography practices.

5. Conclusions

The frontline radiology caregivers within the eThekwini district of KZN, South Africa identified problem-focused coping as their mostly preferred strategies for dealing with physical-based COVID-19 related challenges within their control. Where no practical solutions were feasible, radiology caregivers resorted to emotion-focused strategies to cope with the resultant mental distress and anxiety. This informs future crisis preparedness by alluding to ways in which radiology and hospital management can support staff in coping. This includes practical measures to address staff shortages, ensuring adequate supply of IPC wear and protocols and inclusion of staff in strategy implementation to ensure that solutions are bespoke. Staff motivation and mental support should be prioritised. Mental support interventions should be tailored around staff’s preference by strategising ways of promoting better work-life balance, promoting teamwork and support as well as private spaces for prayer within the institutions. Moreover, it is recommended that the causes of the non-uptake of tertiary interventions such as psychological counselling be explored to increase use and suitability of the service to the population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.N.H., M.N.S. and T.E.K.; methodology, S.N.H.; software, S.N.H.; validation, S.N.H., M.N.S. and T.E.K.; formal analysis, S.N.H.; investigation, S.N.H.; resources, S.N.H.; data curation, S.N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.H., M.N.S. and T.E.K.; writing—review and editing, S.N.H.; M.N.S. and T.E.K.; visualisation, S.N.H.; supervision, M.N.S., T.E.K; project administration, S.N.H., M.N.S. and T.E.K; funding acquisition, S.N.H and M.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of [Masked for blind review] (Ref XX ; Approved on XX) [Masked for blind review].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S.N.H, due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr L. Mudadi for assisting with the data analysis and the frontline radiology caregivers who participated in the study regardless of their busy schedules.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ramphul, K.; Mejias, S.G.; Ramphul, Y. Headache may not be linked with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). World J Emerg Med 2020, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Cheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Bai, H.; Cai, Z.; Yang, B.; Hu, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, G.; Ma, C.; Liu, Z. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain, Behaviour, and Immunity 2020, 87, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardo, M.; Martini, C.; Monti, C.B.; Cattaneo, F.; Ciaralli, C.; Cornacchione, P.; Durante, S. Management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in the radiology department. Radiography 2020, 26, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ding, N.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.J.; He, W.J.; Dai, W.C.; Zhou, Z.G.; Lin, F.; Pu, Z.H.; Li, D.F.; Xu, H.J.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, H.W; Lei, Y. Infection Control against COVID-19 in Departments of Radiology. Academic Radiology 2020, 27, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.; Mulla, F. Diagnostic radiographers' experience of COVID-19, Gauteng South Africa. Radiography 2020, 27, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinene, B. Experiences of Radiographers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Int J Med Rev 2023, 10, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akudjedu, T.N.; Mishio, N.A.; Elshami, W.; Culp, M.P.; Lawal, O.; Botwe, B.O.; Wuni, A.R.; Julka-Anderson, N.; Shanahan, M.; Totman, J.J.; Franklin, J.M. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical radiography practice: A systematic literature review and recommendations for future services planning. Radiography 2021, 27, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.; Moore, N.; Leamy, B.; England, A.; O'Connor, O.J.; McEntee, M.F. An evaluation of the impact of the Coronavirus (COVID 19) pandemic on interventional radiographers' wellbeing. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 2022, 53, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Venter, R.; Williams, R.; Stindt, C.; ten Ham-Baloyi, W. Coronavirus-related anxiety and fear among South African diagnostic radiographers working in the clinical setting during the pandemic. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 2021, 52, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, N.P. Occupational stressors in diagnostic radiographers working in public health facilities in the eThekwini district of KwaZulu-Natal. Masters, Durban University of Technology, South Africa. 2015. Available online: http://ir.dut.ac.za/handle/10321/1414 (accessed on 02 November 2023).

- Fishman, M.D.C.; Mehta, T.S.; Siewert, B.; Bender, C.E.; Kruskal, J.B. The Road to Wellness: Engagement Strategies to Help Radiologists Achieve Joy at Work. RadioGraphics 2018, 38, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, C. A. New Mental Health Policy for South Africa. Mental Health Matters 2023, 10. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental health. Fact Sheet, Mental-health strengthening our response. Geneva. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 03 November 2023).

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company: New York, United States of America, 1984; pp. 1–225.

- Kagwe, M.; Ngigi, S.; Mutisya, S. Sources of Occupational Stress and Coping Strategies among Teachers in Borstal Institutions in Kenya. Edelweiss Psyi Open Access 2018, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, K.; Barroso, J.; Phillips, S. The Experiences of Parents in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Integrative Review of Qualitative Studies Within the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2019, 33, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.D; Grasso, D.J.; Elhai, J.D.; Courtois, C.A. Social, cultural, and other diversity issues in the traumatic stress field. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder 2015, 503–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Katona, C.; Orrell, M.; Livingston, G. Coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease: the LASER-AD study. J Affect Disord 2006, 90, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Blackman, D. A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv Biol 2014, 28, 1167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: Sage Publications: London, Greater London, 2022; 1-125.

- Pietkiewicz, I.; Smith, J. A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal 2014, 20, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods, 2nd ed.; Smith, J.A., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, United Kingdom, 2008; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Christensen, L. Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: California, United States of America, 2014; pp. 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. The Fundamentals in an introduction to triangulation. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/10_4-Intro-to-triangulation-MEF.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Creswell, J.W. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: California, United States of America, 2014; pp. 235–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ashong, G.G.N.A.; Rogers, H.; Botwe, B.O.; Anim-Sampong, S. Effects of occupational stress and coping mechanisms adopted by radiographers in Ghana. Radiography 2016, 22, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidiji, O. A.; Atalabi, O. M.; Idowu, E. A.; Ishola, A.; Olowoyeye, O. A.; Omisore, A. D.; Eze, K. C.; Ahmadu, M. S.; Dim, N. R.; Anas, I.; Ilo, A. C.; Ayodele, S. A. T.; Daji, F. Y.; Yidi, A. M.; Ajiboye, O. K.; Jimoh, K. O.; Toyobo, O. O.; Onuwaje, A. M.; Irurhe, N. K.; Adeyomoye, A. O.; Arogundade, R. A. COVID-19: Challenges and coping strategies in radiology departments in Nigeria. Annals of African medicine 2022, 21, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.A.C.; Supar, R.; Sharip, H.; Ammani, Y.M. Occupational Stress and coping Strategies among Radiographers. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 2023, 8, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleaga, L. How is the pandemic affecting radiology practice? Health Manag 2020, 20, 310–312, Available:https://healthmanagement.org/c/healthmanagement/issuearticle/how-is-the-pandemic-affectingradiology-practice. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, A.; Arif, K.; Sarfraz, S.; Javed, A.; Ikram, M.; Ihsan, A. Challenges and Coping Strategies of Radiology Doctors During COVID-19 Era, Lahore, Pakistan. Journal of Ecophysiology and Occupational Health 2022, 22, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanjee, C.R.; Hartzer, Y.F.; Uys, I.L. The effect of perceived organizational support on organizational commitment of diagnostic imaging radiographers. Radiography 2006, 12, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcleod, S. Attribution Theory in Psychology: Definition & Examples. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/attribution-theory.html (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Woerner, A.; Chick, J.F.B.; Monroe, E.J.; Ingraham, C.R.; Pereira, K.; Lee, E.; Hage, A.N.; Makary, M.S.; Shin, D.S. Interventional Radiology in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Impact on Practices and Wellbeing. Acad Radiol 2021, 28, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennessy, F.M.; Mandell, J.C.; Boland, G.W.; Seltzer, S.E.; Giess, C.S. Strategies to Increase Resilience, Team Building, and Productivity Among Radiologists During the COVID-19 Era. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021, 18, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).