Submitted:

08 February 2024

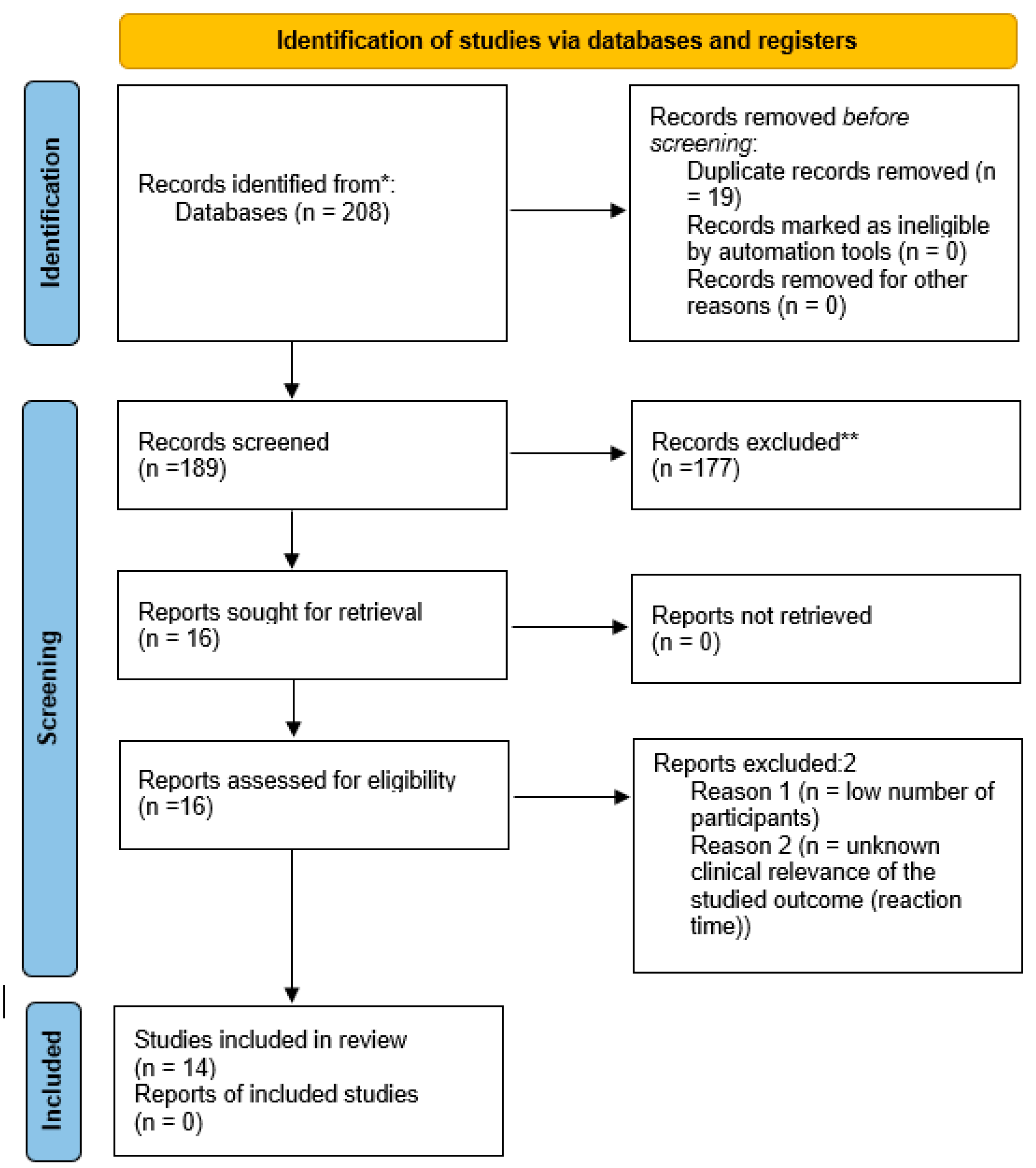

Posted:

09 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Secular trends in plant-based diets in children

3. Associations of plant-based diets with child health outcomes

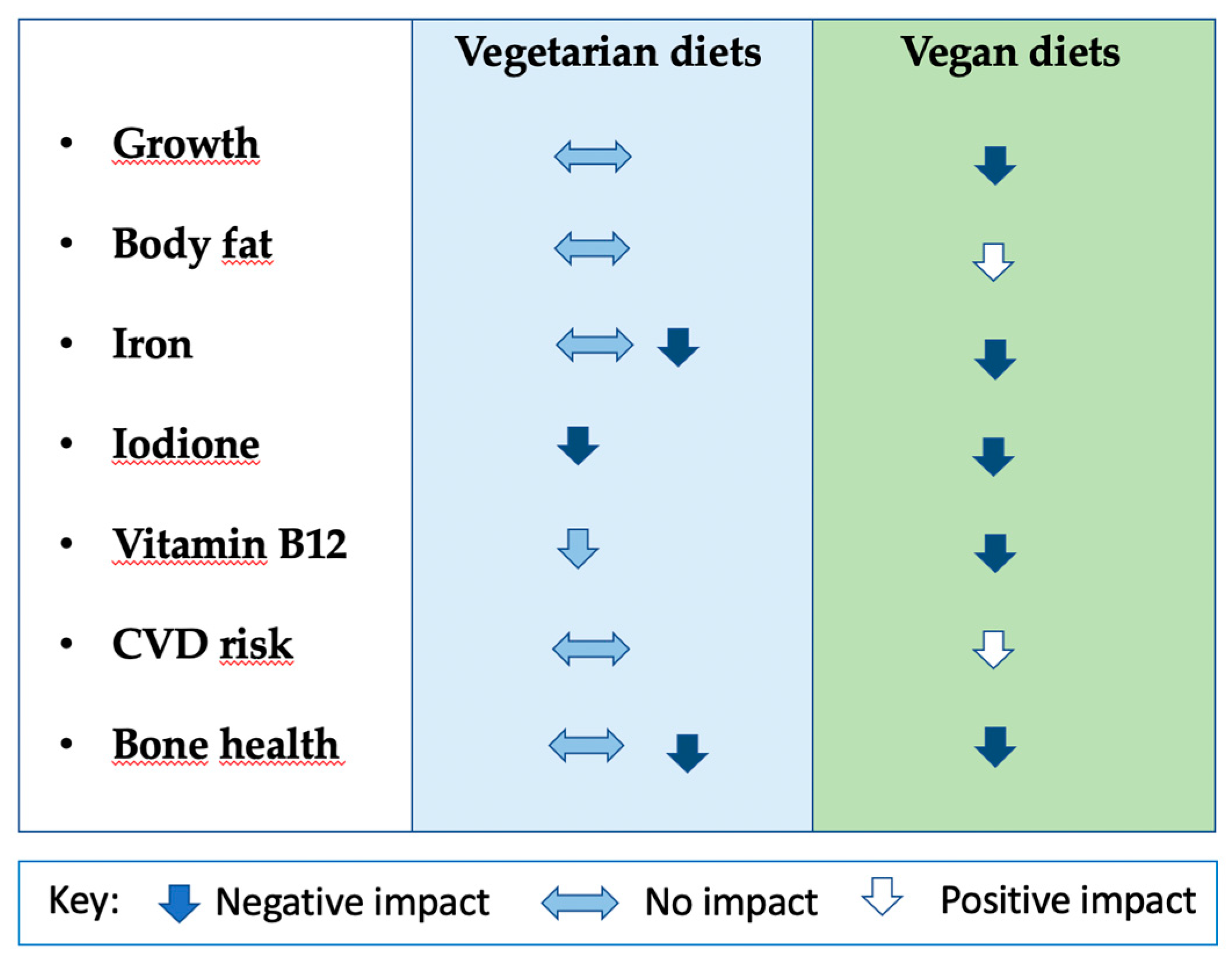

3.1. Body composition and anthropometry

3.2. Bone health

3.3. Nutritional biomarkers

3.4. Cardiometabolic risk factors

3.4.1. Assessment of bias

3.4.2. Conflicting position statements of medical and nutritional institutions around the world

4. Roadmap for future research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment A Review of the Evidence WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; 2021.

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarborough, P.; Clark, M.; Cobiac, L.; Papier, K.; Knuppel, A.; Lynch, J.; Harrington, R.; Key, T.; Springmann, M. Vegans, Vegetarians, Fish-Eaters and Meat-Eaters in the UK Show Discrepant Environmental Impacts. Nat. Food 2023 47 2023, 4, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO The Global Dairy Sector: Facts.; 2013.

- Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock – A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; 2013.

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Chaltiel, D.; Wang, J.; Pointereau, P.; Langevin, B.; Allès, B.; Rebouillat, P.; Lairon, D.; Vidal, R.; Mariotti, F.; et al. Sustainability Analysis of French Dietary Guidelines Using Multiple Criteria. Nat. Sustain. 2020 35 2020, 3, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietitians Australia National Nutrition Strategy Joint Position Statement. Available online: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/advocacy-and-policy/joint-position-statements/national-nutrition-strategy-joint-position-statement (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- European Comission Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Europe - Table 10 | Knowledge for Policy. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/food-based-dietary-guidelines-europe-table-19_en (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Business Insider Poland Światowy Dzień Wegetarianizmu - Wegetarianizm w Polsce. Available online: https://businessinsider.com.pl/rozwoj-osobisty/zdrowie/swiatowy-dzien-wegetarianizmu-wegetarianizm-w-polsce/r27z9fq (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Lantern Papers The Green Revolution, Entendiendo El Auge Del Movimiento Veggie; 2020.

- Cornell University Veganism and Plant-Based Diets On the Rise . Available online: https://blogs.cornell.edu/info2040/2019/11/21/veganism-and-plant-based-diets-on-the-rise/ (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Vegconomist.com 2023.

- Mascaraque, M. Going Plant-Based: The Rise of Vegan and Vegetarian Food; 2020.

- Neufingerl, N.; Eilander, A. Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürmann, S.; Kersting, M.; Alexy, U. Vegetarian Diets in Children: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M.A.; Sobiecki, J.G.; Jaworski, M.; Płudowski, P.; Antoniewicz, J.; Shirley, M.K.; Eaton, S.; Ksiązyk, J.; Cortina-Borja, M.; De Stavola, B.; et al. Growth, Body Composition, and Cardiovascular and Nutritional Risk of 5- to 10-y-Old Children Consuming Vegetarian, Vegan, or Omnivore Diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weder, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Becker, K.; Alexy, U.; Keller, M. Energy, Macronutrient Intake, and Anthropometrics of Vegetarian, Vegan, and Omnivorous Children (1–3 Years) in Germany (VeChi Diet Study). Nutrients 2019, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GFI (Good Food Instititute) 2021 U.S. Retail Market Insights. Plant Based Foods.; 2021.

- Morency, M.E.; Birken, C.S.; Lebovic, G.; Chen, Y.; L’Abbé, M.; Lee, G.J.; Maguire, J.L. Association between Noncow Milk Beverage Consumption and Childhood Height. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crimarco, A.; Landry, M.J.; Carter, M.M.; Gardner, C.D. Assessing the Effects of Alternative Plant-Based Meats v. Animal Meats on Biomarkers of Inflammation: A Secondary Analysis of the SWAP-MEAT Randomized Crossover Trial. J. Nutr. Sci. 2022, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiega-Franyutti, P.; Freyre-Fonseca, V. Chronic Consumption of Food-Additives Lead to Changes via Microbiota Gut-Brain Axis. Toxicology 2021, 464, 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.S.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Karavasiloglou, N.; Jennings, A.; Cantwell, M.; Hill, C.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Bondonno, N.P.; Murphy, N.; Rohrmann, S.; et al. Association of Healthful Plant-Based Diet Adherence With Risk of Mortality and Major Chronic Diseases Among Adults in the UK. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e234714–e234714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BDA British Dietetic Association Confirms Well-Planned Vegan Diets Can Support Healthy Living in People of All Ages. Available online: https://www.bda.uk.com/news/view?id=179 (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Medécine de Belgique, A.R. Le {Veganisme} Proscrit Pour Les Enfants, Femmes Enceintes et Allaitantest 2019.

- Die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung Vegane Ernährung: Nährstoffversorgung Und Gesundheitsrisiken Im Säuglings- Und Kindesalter.

- Wądołowska, L. et al. Stanowisko Komitetu Nauki o Żywieniu Człowieka PAN w Sprawie Wartości Odżywczej i Bezpieczeństwa Stosowania Diet Wegetariańskich E; Olsztyn, 2019.

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Panza, R.; Farella, I.; Posa, D.; Capozza, M.; Di Mauro, A.; Laforgia, N. Vegetarian and Vegan Weaning of the Infant: How Common and How Evidence-Based? A Population-Based Survey and Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Startseite AWA - AWA – Allensbacher Markt- Und Werbeträgeranalyse. Available online: https://www.ifd-allensbach.de/awa/startseite.html (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Department of Health and the Food Standars Agency National Diet and Nutrition Survey Headline Results from Years 1 and 2 (Combined) of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009 – 2009/10); 2010.

- Stewart, C.; Piernas, C.; Cook, B.; Jebb, S.A. Trends in UK Meat Consumption: Analysis of Data from Years 1–11 (2008–09 to 2018–19) of the National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2021, 5, e699–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintel Vegan Food Launches in Australia Grew by 92% between 2014 and 2016. Available online: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/vegan-food-launches-in-australia-grew-by-92-between-2014-and-2016/ (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- GFI (Good Food Instititute) UK Plant- Based Foods Retail Market Insights 2020-2022; 2022.

- BBC Good Food Nation: Survey Looks at Children’s Eating Habits - BBC Newsround. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/58653757 (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Chiorando, M. 70% of British Children Want More Vegan and Veggie School Meals, Says Poll. Plant Based News 2020.

- Nathan, I.; Hackett, A.F.; Kirby, S. A Longitudinal Study of the Growth of Matched Pairs of Vegetarian and Omnivorous Children, Aged 7-11 Years, in the North-West of England. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 51, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcovicová-Kudlácková, M.; Simoncic, R.; Béderová, A.; Grancicová, E.; Magálová, T. Influence of Vegetarian and Mixed Nutrition on Selected Haematological and Biochemical Parameters in Children. Nahrung 1997, 41, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Klemarczyk, W.; Gajewska, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Rowicka, G.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Laskowska-Klita, T. Serum Concentration of Adipocytokines in Prepubertal Vegetarian and Omnivorous Children. Med. Wieku Rozwoj. 2011, 15, 326–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hebbelinck, M.; Clarys, P.; De Malsche, A. Growth, Development, and Physical Fitness of Flemish Vegetarian Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 579s–585s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Laskowska-Klita, T.; Klemarczyk, W. Low Levels of Osteocalcin and Leptin in Serum of Vegetarian Prepubertal Children. Med. Wieku Rozwoj. 2003, 7, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Klemarczyk, W.; Chełchowska, M.; Gajewska, J.; Laskowska-Klita, T. Serum Homocysteine, Folate, Vitamin B12 and Total Antioxidant Status in Vegetarian Children. Adv. Med. Sci. 2006, 51, 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Klemarczyk, W.; Gajewska, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Laskowska-Klita, T. Serum Concentration of Biochemical Bone Turnover Markers in Vegetarian Children. Adv. Med. Sci. 2007, 52, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gorczyca, D.; Paściak, M.; Szponar, B.; Gamian, A.; Jankowski, A. An Impact of the Diet on Serum Fatty Acid and Lipid Profiles in Polish Vegetarian Children and Children with Allergy. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczyca, D.; Prescha, A.; Szeremeta, K.; Jankowski, A. Iron Status and Dietary Iron Intake of Vegetarian Children from Poland. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 62, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, T.A. Growth and Development of British Vegan Children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1988, 48, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, I.; Hackett, A.; Kirby, S. The Dietary Intake of a Group of Vegetarian Children Aged 7-11 Years Compared with Matched Omnivores. Br. J. Nutr. 1996, 75, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Redworth, E.W.; Morgan, J.B. Influence of Diet on Iron, Copper, and Zinc Status in Children Under 24 Months of Age. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004, 97, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.D.; Phillips, R.L.; Williams, P.M.; Kuzma, J.W.; Fraser, G.E. The Child-Adolescent Blood Pressure Study: I. Distribution of Blood Pressure Levels in Seventh-Day-Adventist (SDA) and Non-SDA Children. Am. J. Public Health 1981, 71, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, D.G.; Sanchez, A. The Association of Dietary Factors with the Age of Menarche. Nutr. Res. 1987, 7, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, J.M.; Dibley, M.J.; Sierra, J.; Wallace, B.; Marks, J.S.; Yip, R. Growth of Vegetarian Children: The Farm Study. Pediatrics 1989, 84, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, K.A.; Olson, A.L.; Nelson, S.E.; Rebouche, C.J. Carnitine Status of Lactoovovegetarians and Strict Vegetarian Adults and Children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 50, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, J.; Lindsted, K.D.; Harris, R.D.; Sanchez, A. Attained Height of Lacto-Ovo Vegetarian Children and Adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 45, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté, J.; Llorca, M.C.; Sánchez, A. Lower Height of Lacto-Ovovegetarian Girls at Preadolescence: An Indicator of Physical Maturation Delay? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1992, 92, 1263–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persky, V.W.; Chatterton, R.T.; Van Horn, L.V.; Grant, M.D.; Langenberg, P.; Marvin, J. Hormone Levels in Vegetarian and Nonvegetarian Teenage Girls: Potential Implications for Breast Cancer Risk. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 578–583. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, V.; Wien, M.; Sabaté, J. The Risk of Child and Adolescent Overweight Is Related to Types of Food Consumed. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, E.; Dörner, K.; Hamm, E.; Hanisch, C.; Schaub, J. Vergleichende Untersuchungen Zur Eisenversorgung Lakto-Ovo-Vegetabil Ernährter Säuglinge. Ärztezeitschr Naturheilverf 1991, 32, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weder, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Becker, K.; Alexy, U.; Keller, M. Energy, Macronutrient Intake, and Anthropometrics of Vegetarian, Vegan, and Omnivorous Children (1–3 Years) in Germany (VeChi Diet Study). Nutrients 2019, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovinen, T.; Korkalo, L.; Freese, R.; Skaffari, E.; Isohanni, P.; Niemi, M.; Nevalainen, J.; Gylling, H.; Zamboni, N.; Erkkola, M.; et al. Vegan Diet in Young Children Remodels Metabolism and Challenges the Statuses of Essential Nutrients. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.; Sandullo, F.; Vecchio, M.; Di Ruscio, F.; Franceschini, G.; Peronti, B.; Blasi, V.; Nonni, G.; Bietolini, S. Length-Weight Growth Analysis up to 12 Months of Age in Three Groups According to the Dietary Pattern Followed from Pregnant Mothers and Children during the First Year of Life. Minerva Pediatr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexy, U.; Fischer, M.; Weder, S.; Längler, A.; Michalsen, A.; Sputtek, A.; Keller, M. Nutrient Intake and Status of German Children and Adolescents Consuming Vegetarian, Vegan or Omnivore Diets: Results of the Vechi Youth Study. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Světnička, M.; Heniková, M.; Selinger, E.; Ouřadová, A.; Potočková, J.; Kuhn, T.; Gojda, J.; El-Lababidi, E. Prevalence of Iodine Deficiency among Vegan Compared to Vegetarian and Omnivore Children in the Czech Republic: Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Světnička, M.; Sigal, A.; Selinger, E.; Heniková, M.; El-lababidi, E.; Gojda, J. Cross-Sectional Study of the Prevalence of Cobalamin Deficiency and Vitamin B12 Supplementation Habits among Vegetarian and Vegan Children in the Czech Republic. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.J.; Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G.; Birken, C.S.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Borkhoff, C.M.; Maguire, J.L. Vegetarian Diet, Growth, and Nutrition in Early Childhood: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2022, 149, 2021052598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexy, U.; Fischer, M.; Weder, S.; Längler, A.; Michalsen, A.; Sputtek, A.; Keller, M. Nutrient Intake and Status of German Children and Adolescents Consuming Vegetarian, Vegan or Omnivore Diets: Results of the VeChi Youth Study. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaté, J.; Lindsted, K.; Harris, R.; Johnston, P. Anthropometric Parameters of Schoolchildren With Different Life-Styles. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1990, 144, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Strucińska, M.; Kawiak-Jawor, E.; Weker, H.; Chełchowska, M. Assessment of Oxidant and Antioxidant Status in Prepubertal Children Following Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Klemarczyk, W.; Mazur, J.; Gajewska, J.; Rowicka, G.; Strucińska, M.; Chełchowska, M. Serum Hepcidin and Soluble Transferrin Receptor in the Assessment of Iron Metabolism in Children on a Vegetarian Diet. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 180, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Szamotulska, K.; Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Strucińska, M.; Gajewska, J. The Assessment of Bone Regulatory Pathways, Bone Turnover, and Bone Mineral Density in Vegetarian and Omnivorous Children. Nutrients 2018, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Strucińska, M.; Gajewska, J. Anti-Inflammatory and Pro-Inflammatory Adipokine Profiles in Children on Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Szamotulska, K.; Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Strucińska, M.; Gajewska, J. Bone Status and Adipokine Levels in Children on Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroke, A.; Manz, F.; Kersting, M.; Remer, T.; Sichert-Hellert, W.; Alexy, U.; Lentze, M.J. The DONALD Study. History, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Eur. J. Nutr. 2004, 43, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Gajewska, J.; Mazur, J.; Kuśmierska, K.; Klemarczyk, W.; Rowicka, G.; Strucińska, M.; Chełchowska, M. Dietary Intake and Circulating Amino Acid Concentrations in Relation with Bone Metabolism Markers in Children Following Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Szamotulska, K.; Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Strucińska, M.; Gajewska, J. The Assessment of Bone Regulatory Pathways, Bone Turnover, and Bone Mineral Density in Vegetarian and Omnivorous Children. Nutrients 2018, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Szamotulska, K.; Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Strucińska, M.; Gajewska, J. The Assessment of Bone Regulatory Pathways, Bone Turnover, and Bone Mineral Density in Vegetarian and Omnivorous Children. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weder, S.; Keller, M.; Fischer, M.; Becker, K.; Alexy, U. Intake of Micronutrients and Fatty Acids of Vegetarian, Vegan, and Omnivorous Children (1-3 Years) in Germany (VeChi Diet Study). Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higginbottom, M.C.; Sweetman, L.; Nyhan, W.L. A Syndrome of Methylmalonic Aciduria, Homocystinuria, Megaloblastic Anemia and Neurologic Abnormalities in a Vitamin B 12 -Deficient Breast-Fed Infant of a Strict Vegetarian. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978, 299, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, V.; Bekárek, E.; Hlídková, J.; Bucil, D.; Mayerová, Z.; Skopková, T.; Adam, E.; Hrubá, V.; Kozich, L.; Buriánková, J.; Saligová, M.; Buncová, J.Z. Metabolic Complications and Neurologic Manifestations of Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Children of Vegetarian Mothers. Cas Lek Ces. 2001, 140, 732–735. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, A.; Chalies, S.; Jeziorski, E.; Ludwig, C.; Lalande, M.; Rodière, M. [Consequences of Exclusive Breast-Feeding in Vegan Mother Newborn--Case Report]. Arch. Pediatr. 2009, 16, 1461–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, Vegan Diets and Multiple Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Chełchowska, M.; Rowicka, G.; Klemarczyk, W.; Strucińska, M.; Gajewska, J. Anti-Inflammatory and Pro-Inflammatory Adipokine Profiles in Children on Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakše, B.; Fras, Z.; Fidler Mis, N. Vegan Diets for Children: A Narrative Review of Position Papers Published by Relevant Associations. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havala, S.; Dwyer, J. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian Diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1993, 93, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WJ, C.; AR, M. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian Diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, C.; Baroni, L.; Bertini, I.; Ciappellano, S.; Fabbri, A.; Papa, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Sbarbati, R.; Scarino, M.L.; Siani, V.; et al. Position Paper on Vegetarian Diets from the Working Group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, and B.C. for C. Nutrition for Healthy Term Infants: Recommendations from Six to 24 Months. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2014, 75, 107–107. [CrossRef]

- Amit, M.; Society, C.P.; Committee, C.P. Vegetarian Diets in Children and Adolescents. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 15, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, M.J.; Desantadina, M.V. [Vegetarian Diets in Childhood]. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2020, 118, S130–S141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redecilla Ferreiro, S.; Moráis López, A.; Moreno Villares, J.M.; Leis Trabazo, R.; José Díaz, J.; Sáenz de Pipaón, M.; Blesa, L.; Campoy, C.; Ángel Sanjosé, M.; Gil Campos, M.; et al. [Position Paper on Vegetarian Diets in Infants and Children. Committee on Nutrition and Breastfeeding of the Spanish Paediatric Association]. An. Pediatr. 2020, 92, 306.e1-306.e6. [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Boeing, H.; Grünewald-Funk, D.H.H.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, A.; Oberritter, H.; Strohm, D.W.B.; (DGE), für die D.G. für E. e. V. Vegane Ernährung,Position Der Deutschen Gesellschaft Für Ernährung e. V. (DGE). Ernaehrungs Umschau Int. 2016, M220–M230. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, M., Kroke, A., Grünewald-Funk, D., Heseker, H., Virmani, K., W.B. fü. die D.G. für E. e. V. (DGE) Ergänzung Der Position Der Deutschen Gesellschaft Für Ernährung e. V. Zur Veganen Ernährung Hinsichtlich Bevölkerungsgruppen Mit Besonderem Anspruch an Die Nährstoffversorgung. Ernaehrungs Umschau Int. 2020.

- Lemale, J.; Mas, E.; Jung, C.; Bellaiche, M.; Tounian, P. Vegan Diet in Children and Adolescents. Recommendations from the French-Speaking Pediatric Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Nutrition Group (GFHGNP). Arch. Pediatr. 2019, 26, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgique, A.R. de M. de Le Veganisme Proscrit Pour Les Enfants, Femmes enceintes et Allaitantest 2019.

- Szajewska, H., Socha, P. and H.A. Principles of Feeding Healthy Infants. Statement of the Polish Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition for Children (in Polish). Stand Med/Pediatria 2021, 805–822.

- Hay, G.; Fadnes, L.; Meltzer, H.M.; Arnesen, E.K.; Henriksen, C. Follow-up of Pregnant Women, Breastfeeding Mothers and Infants on a Vegetarian or Vegan Diet. Tidsskr. den Nor. laegeforening Tidsskr. Prakt. Med. ny raekke 2022, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fewtrell, M.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.; Mis, N.F.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.M.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; et al. Complementary Feeding: A Position Paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely, M.E. Risks and Benefits of Vegan and Vegetarian Diets in Children. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, R.; Bell, K. Iron {Status} of {Vegetarian} {Children}: {A} {Review} of {Literature}. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 70, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors, year, place | Study characteristics | Participants | Dietary data collection | Health outcomes measured | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambroszkiewicz et al. 2017. The Institute of Mother and Child (IMC) in Warsaw, Poland [68]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2015-2016; from a group of patients seeking dietary counselling at the IMC. | 43 vegetarian (VG) prepubertal children (age range 4.5–9.0 years), 46 omnivore (OM) children. No data on socio-economic status (SES) or physical activity (PA). | 3-day food diary, data on average daily energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates, dietary iron and vitamin intakes collected. | Serum haemoglobin (Hb), red blood cells, and mean corpuscular volume, iron, ferritin, and transferrin, C-reactive protein (CRP), hepcidin (bioactive heptidin-25 molecule) and soluble transferrin receptor concentration (sTfR); weight (WT), height (HT) | Lower ferritin and median hepcidin concentrations in VG; sTfR concentrations significantly higher in VG compared to OM. No difference in serum transferrin between groups; other hematologic parameters and serum iron were within the reference range in both groups. No differences in WT, HT, BMI between VG and OM. |

| Ambroszkiewicz et al 2018. The IMC, Warsaw, Poland [69]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2014-2017; from a group of patients seeking dietary counselling at the IMC. | 70 children (age range 5–10 years) on a VG diet from birth, 60 OM children. No data on SES. PA study inclusion criteria – more than 2h of activity per week. No information on how this data was collected. | 3-day food diary, data on average daily energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates, and dietary minerals and vitamin intakes collected. | Bone mineral content (BMC), and bone mineral density (BMD) in the total body (tBMD) and at the lumbar spine (BMD L1–L4), lean and fat mass by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA); height, weight; bone alkaline phosphatase (BALP), C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX-I), osteoprotegerin, nuclear factor κB ligand, sclerostin, and Dickkopf-related protein 1; 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OH D) and parathormone (PTH); HT and WT. | No significant differences in body composition, HT, BMI z-scores or BMC and BMD, 25-OH D between VG and OM children, however a trend for spine BMC and BMD of VG to be lower; VG significantly higher level of BALP and CTX-I (interpreted as a higher rate of bone turnover markers) and higher median levels of PTH) than OM. |

| Ambroszkiewicz et al. 2018. The IMC, Warsaw, Poland [70]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2017-2018; from a group of patients seeking dietary counselling at the IMC. | 62 children (age range 5–10 years) on a VG diet from birth, 55 OM children. No data on SES. PA assessed by questionnaire. | 3-day food diary, data on average daily energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates, and dietary fibre intake collected. | Serum concentrations of adipokines: leptin, soluble leptin receptor (sOB-R), adiponectin, resistin, visfatin, vaspin, and omentin; fat mass, lean mass, and fat free mass by DXA; fat mass index and lean mass index were calculated; HT and WT. | No difference in WT, HT, BMI, and body composition between groups. VG had lower leptin/sOB-R ratio and lower serum concentrations of resistin, compared with OM; average levels of other adipokines did not differ between both groups; VG had significantly higher ratios of anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory adipokines: adiponectin/leptin and omentin/leptin compared with OM. |

| Ambroszkiewicz et al. 2019. The IMC, Warsaw, Poland [71]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2014-2016; from a group of patients seeking dietary counselling at the IMC. | 53 children (age range 5–10 years) on a VG diet, 53 OM children. No data on SES. PA assessed by questionnaire. | 3-day food diary, data on average daily energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates, and dietary minerals and vitamin intakes collected. Complete dietary data was available for 25 pairs of VG & OM. | WT, HT; body composition and BMD by DXA. 25-OH D and PTH, serum carboxy-terminal propeptide of type I collagen (CICP), total osteocalcin and its forms carboxylated and undercarboxylated, CTX-I, leptin and adiponectin levels. | No difference in HT, WT, BMI z-scores or body composition between VG and OM, except for percentage fat mass, lower in VG. Mean total BMD z-score and lumbar spine BMD z-score were lower in VG compared with OM; however absolute values of bone mineral density did not differ; serum leptin level was 2-fold lower in VGs, reflecting lower body fat; VG had higher PTH and CTX; similar levels of adiponectin, osteocalcin, CICP, and 25 (OH) D; BMD z-scores did not correlate with bone metabolism markers and nutritional variables, but were positively associated with anthropometric parameters. |

| Weder et al. 2019. The VeChi DietStudy, Germany [58]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2016-2018, collecting data from VG, VN, and OM children throughout Germany. OM children partially recruited from the DONALD [72] study (as insufficient OM participants were recruited via the VeChi Study). | 430 children: 127 VG,139 vegan (VN), 164 OM, aged 1-3 years. SES and urbanicity data collected. PA assessed by questionnaire. | 3-day weighed dietary records; breast milk intakes were estimated with the methodology from the DONALD study [72]. Energy, macronutrients, and fibre intakes were calculated. | Data from parents or a paediatrician proxy-assessed WT and HT during the last medical check-up. | Anthropometrics did not significantly differ between diet groups and indicated on average normal growth in all groups. However, more VN (3.6%) and VG (2.4%) than OM children (0%) were classified as stunted or wasted. |

| Hovinen et al. 2021. Municipal day-care centres, Helsinki, Finland [59]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2017, from 20 municipal day-care centres offering vegan meals in Helsinki. | 6 VN (vegan from birth); 10 VG, 24 OM; median age 3.5 years (1-7 years). Vegetarian children defined as those on a lactovegetarian diet or on a pescetarian diet (eating fish). No data on PA or SES. | The children were consuming nutritionist-planned diets in day-care centres, designed to meet nutritional recommendations. | WT, HT, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC); numerous biomarkers. Serum amino acids, vitamin A, 25 (OH)D, DHA, and other micronutrients; total cholesterol, HDL -C and LDL -C, endogenous hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis markers, bile acid biosynthesis markers. | HT and BMIs of all children compared to the current Finnish growth references; there was no difference between diet groups in z-scores of HT, BMI, or MUAC. All fractions of blood lipid levels were significantly lower in VN than OM. Biomarkers for amino acids, fat-soluble vitamins A, D and DHA were markedly lower in VN. Bile acid biosynthesis pathway differed most significantly between VN and OM, VN had a bile acid pathway similar to a profile of fasted children. |

| Ferrara et al. 2021. Italy [60]. | Longitudinal study of infants born to mothers on VN, VG and OMN study, follow up in the first year of life; data collection 2017-2018. Participants recruited via the Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Romand vegetarian societies. | 63 participants: 21 infants from vegan pregnancies; 21 infants from vegetarian pregnancies; 21 infants from omnivorous pregnancies. | Food frequency questionnaire to classify mothers to appropriate dietary pattern. | Weight at birth, 6 months and 12 months (in grams and in growth percentiles); birth length in cm, body length expressed in growth percentiles at 12 months; BMI at 6 months. |

Vegan infants had lower birthweight, weight at 6 months and 12 months, both when expressed in grams and when expressed in growth percentiles than OMN infants. VN infants had lower body length expressed in growth percentiles at 12 months and lower BMI at 6 months than OMN. N significant differences between OMN and VG. |

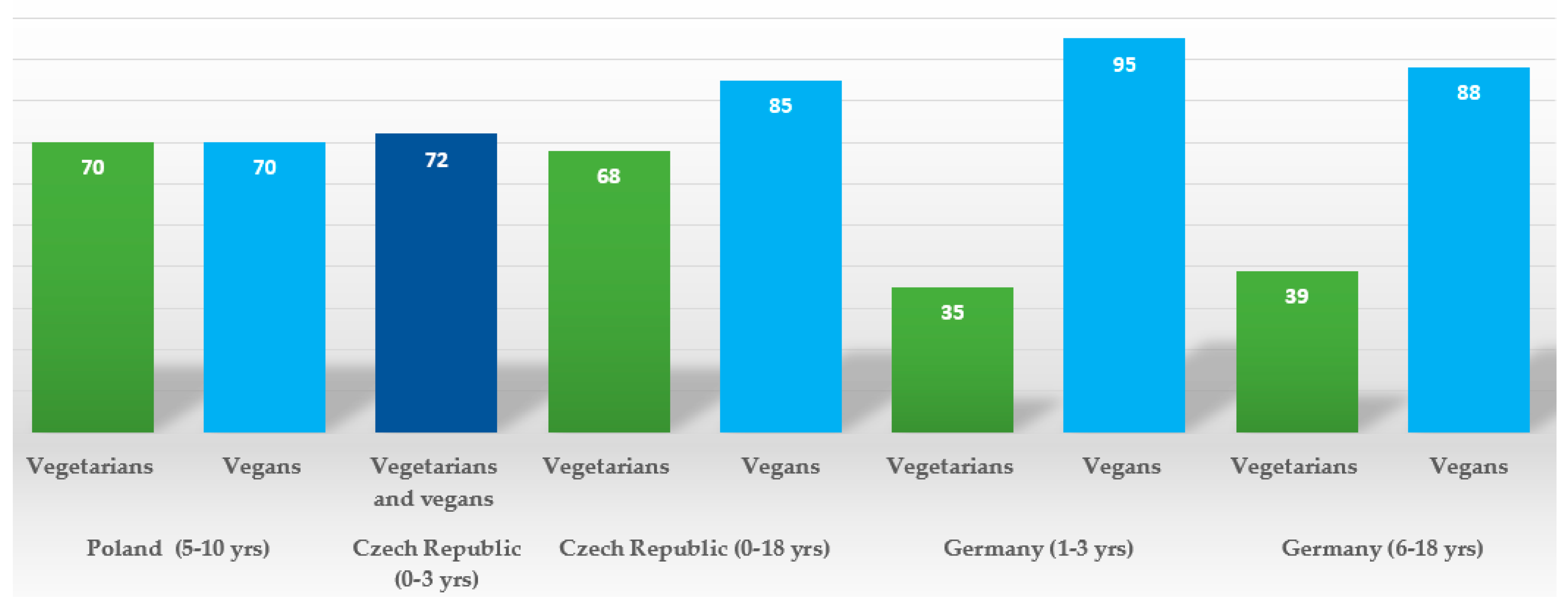

| Alexy et al. 2021. The VeChi Youth Study, Germany [65]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2016-2018, collecting data from VG, VN, and OM children throughout Germany. | 401 children: 149 VG; 115 VN; 137 OM; 6-18 years old, mean age: 12.7 ± 3.9 years; average time on a diet ca. 5.0 (± 3.9) years for vegetarians, and 4.2 (± 3,4) years for vegans. SES and urbanicity data collected. PA assessed by questionnaire. | 3-day weighed dietary records; energy, macronutrients, and selected micronutrients were calculated along with supplement use. | HT, WT; blood parameters: Hb, vitamin B2, and folate; ferritin, 25 (OH)D, holotranscobalamin (holoTC), methylmalonic acid (MMA), triglycerides TG) and total, LDL and HDL cholesterol. | No difference in average HT, WT, BMI z scores, however tendency for the lower values in VN; no significant difference in median Hb, vitamin B2, 25 (OH)D, HDL-C and TG concentrations between diet groups. VN had higher folate concentrations than VG; VN and VG had lower ferritin concentration than OM; VG but not VN had lower concentrations of holoTC and higher concentrations of MMA than OM, reflecting high (88%) vit. B12 supplementation prevalence in VN, but not in VG (39%). VN had the lowest non-HDL-C and LDL-C concentrations in comparison to VG and OM. A high prevalence (>30%) of 25 (OH)D and vitamin B2 concentrations below reference values were found irrespective of the diet group, however that percentage tended to be higher in VN and/or VG than in OM. |

| Desmond et al. The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, Poland [16]. |

Cross-sectional, data collection 2014-2016; recruited advertisements in social media, and websites focused on veganism (VG and VG; and health food stores (OM). OM matched to either VN or VG on age, sex and 2 indices of socio-economic status. | 187 children: 63 VG, 52 VN, 72 OM; age 5-10 years. Average time on a diet ca. 5.3 years for vegetarians, and 5.9 years for vegans. SES and urbanicity data collected. PA data collected by accelerometery. | 4 -day food diary, animal product consumption screener; energy, macro- and most micronutrient intakes along with supplemental practices were ascertained. | Body composition (BC): HT, WT, mid-thigh, waist, and hip girths; and biceps, triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac skinfolds; additionally BC by deuterium dilution and DXA. Cardiovascular risk factors: serum total cholesterol (TC), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), VLDL cholesterol (VLDL- C), and triglycerides (TG), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), fasting glucose, IGF-1, IGFBP-3. Carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) by ultrasonography. Micronutrient status by complete blood count, including mean corpuscular volume (MCV), serum ferritin, vitamin B12, homocysteine (hcys), 25 (OH)D; bone health was assessed by DXA (bone mineral content in total body and spine (L1-L4) adjusted by body size) and calculating bone apparent mineral density (BMAD). | VG had lower gluteofemoral adiposity but similar total fat and lean mass. VN had lower fat indices in all regions, lower fat mass index z-score, but similar lean mass. VG and VN had lower total and L1-L4 BMC, the difference remained only in VN after accounting for body size. VN were on average 3.15 cm shorter than OM. VG had lower TC, HDL-C, and serum B12 and 25(OH)D without supplementation; higher glucose, VLDL, and TG. Vegans were shorter and had lower TC, LDL-C and HDL-C, hs-CRP, iron status, and serum B12 and 25(OH)D without supplementation, but higher hcys and MCV. Vitamin B12 deficiency, iron-deficiency anaemia, low ferritin, and low HDL were more prevalent in vegans, who also had the lowest prevalence of high LDL. Supplementation resolved low B-12 and 25(OH)D concentrations in both groups. |

| Světnička et al. 2022. The Czech Vegan Children Study (CAROTS), Czech Republic [63]. | Cross-sectional, data collection 2019-2021; recruited via GPs and other specialists, advertisements in social media, and websites focused on veganism. | 200 children: 79 VG, 69 VN and 52 OM; age ranging from 0 to 18 years. No data on PA or SES collected. | 3-day weighed dietary records; energy and macro- and micronutrient intakes along with supplemental practices were ascertained; breast milk intakes were estimated from mothers’ registrations and general recommendations for breast milk intake. | WT, HT; blood concentration of holoTC, cyanocobalamin (B12), folate, hcys, MCV, and Hb. | No difference in BMI percentile, HT and WT percentile between groups; VN tended to have lower medians of BMI and weight percentile; significantly more VN were in the <=3 percentile BMI category than in the other two groups; no significant differences in levels of holoTC, folate, hcys, or MCV; 1 VG and 2 VN children identified as B12 deficient; however, 83% of vegan children and 70% vegetarians supplemented vit. B12. In a subgroup of n=12 VG and n=36 VN, age 0-3 years, breastfed at the moment of examination born to VN/VG mothers, concentrations of holoTC, B12, were lower and hcys higher in VN infants not supplementing vit. B12. 35 VG (44%), 28 VN (40%), and 9 OM children had vitamin B12 hypervitaminosis, related to a high prevalence of over-supplementation in the group. Significant difference in B12, holoTC, and hcys levels of supplemented vs. non-supplemented VG/VN children was detected. |

| Světnička et al. 2023. The Czech Republic [62]. | Cross -sectional, data collection 2019-2021; recruited via GPs and other specialists, advertisements in social media, and websites focused on veganism. | 222 children: 91 VG, 75 were VN and 52 OM; age 0 to 18 years. No data on PA or SES collected. | 3-day weighed dietary records to evaluate iodine intake; the use of iodine supplements and their dosages and frequencies were assessed by questionnaire; breast milk intakes were estimated from mothers’ registrations and general recommendations for breast milk intake. | WT, HT. Serum TSH, fT4, fT3, thyroglobulin, and levels of anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (ATPOc) and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (AhTGc) concentration of iodine in spot urine (UIC). | No difference in WT percentile, HT percentile between the groups, but lower BMI z-score in VN and a higher number n = 7 (i.e. 9%) of VN children below the 3rd percentile. No differences in TSH levels, fT3, thyroglobulin or ATPOc between the VG, VN, and OM groups; higher levels of fT4 in VN compared to the OM. The presence of AhTGc was more common in the VG (18.2%)/VN (35.0%) than in the OM group (2.1%). The UIC was found to be highest in the OM group vs. VG and VN. 31 VN, 31 VG and 10 OM children met the criteria for iodine deficiency (i.e., UIC < 100 µg/l). 16.3% vegetarians and 21.8% of vegans took iodine supplements. VN and VG children may be more at higher risk of iodine deficiency, this theory is also supported by higher prevalence of AhTGc positivity. |

| Elliott et al. 2023. The TARGet Kids! cohort study. Canada [64]. |

A longitudinal cohort study. data was collected repeatedly between 2008 and 2019 during scheduled health supervision visits in primary care practices. | 8,907 children, including 248 VG children at baseline; aged 6 months to 8 years. 69% (6175 of 8907) of children had 2 or more measures. Growth data were available on 8794 children. No data on PA or SES collected. | Dietary group assessed by parental self- declaration of the child being on vegetarian or vegan diet. Both were classified as vegetarian (VG). | HT, WT, serum ferritin, 25 (OH)D, and serum lipids (non-HDL-C, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG). | No association between vegetarian diet and BMI z-score, height-for-age z-score, serum ferritin, 25 (OH)D, or serum lipids. VG had higher odds of underweight (BMI z-score <−2); no association of diet with overweight or obesity. |

| Rowicka et al. 2023 The IMC, Warsaw, Poland [67]. |

Cross- sectional; data collection 2020-2021; from a group of patients seeking dietary counselling at the IMC. | 32 VG children (age range 2–10 years) on a vegetarian diet from birth; 40 OM children. No data on SES collected. | 3-day food diary, average daily energy intake, the percentage of energy from protein, fat, and carbohydrates, and vitamin intakes. | HT, WT. Serum CRP, calprotectin, total oxidant capacity (TOC), total antioxidant capacity (TAC), reduced (GSH), and oxidized (GSSG) glutathione; the oxidative stress index (OSI) and the GSH/GSSG ratio were calculated. | No difference in BMI and BMI z-scores between dietary groups; however, VG tended to have lower values. VG had significantly lower median values of TOC, GSH and GSSG as well as CRP, and higher TAC compared with OM. The OSI was significantly lower in VG. |

| Ambroszkiewicz et al. 2023. The IMC, Warsaw, Poland [73]. | Cross-sectional; data collection 2020-2021; from a group of patients seeking dietary counselling at the IMC. | 51 VG, (among the VG group there were 9.6% vegan children) age range 4–9 years); most of them on a vegetarian diet from birth; 25 OM children. No data on SES collected, PA assessed by questionnaire. | 3-day food diary; average daily dietary energy, protein, fiber, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and amino acid intakes were assessed in 61 (80%) of the studied children. | WT, HT; serum amino acids, 25-OH- D, PTH, bone metabolism markers (osteocalcin, CTX-I, osteoprotegerin, IGF-I), albumin, and prealbumin. | No difference in BMI between VG and OM; serum concentrations of 4 amino acids (valine, lysine, leucine, isoleucine) were 10–15% lower in VG than OM; serum differences in amino acid levels were less marked than dietary intake differences. VG had lower (but still normal) serum albumin levels; they also had higher levels of CTX-I (bone resorption marker) than OM. There was no significant difference in other bone metabolism markers or PTH levels between groups. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).