Submitted:

08 February 2024

Posted:

09 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

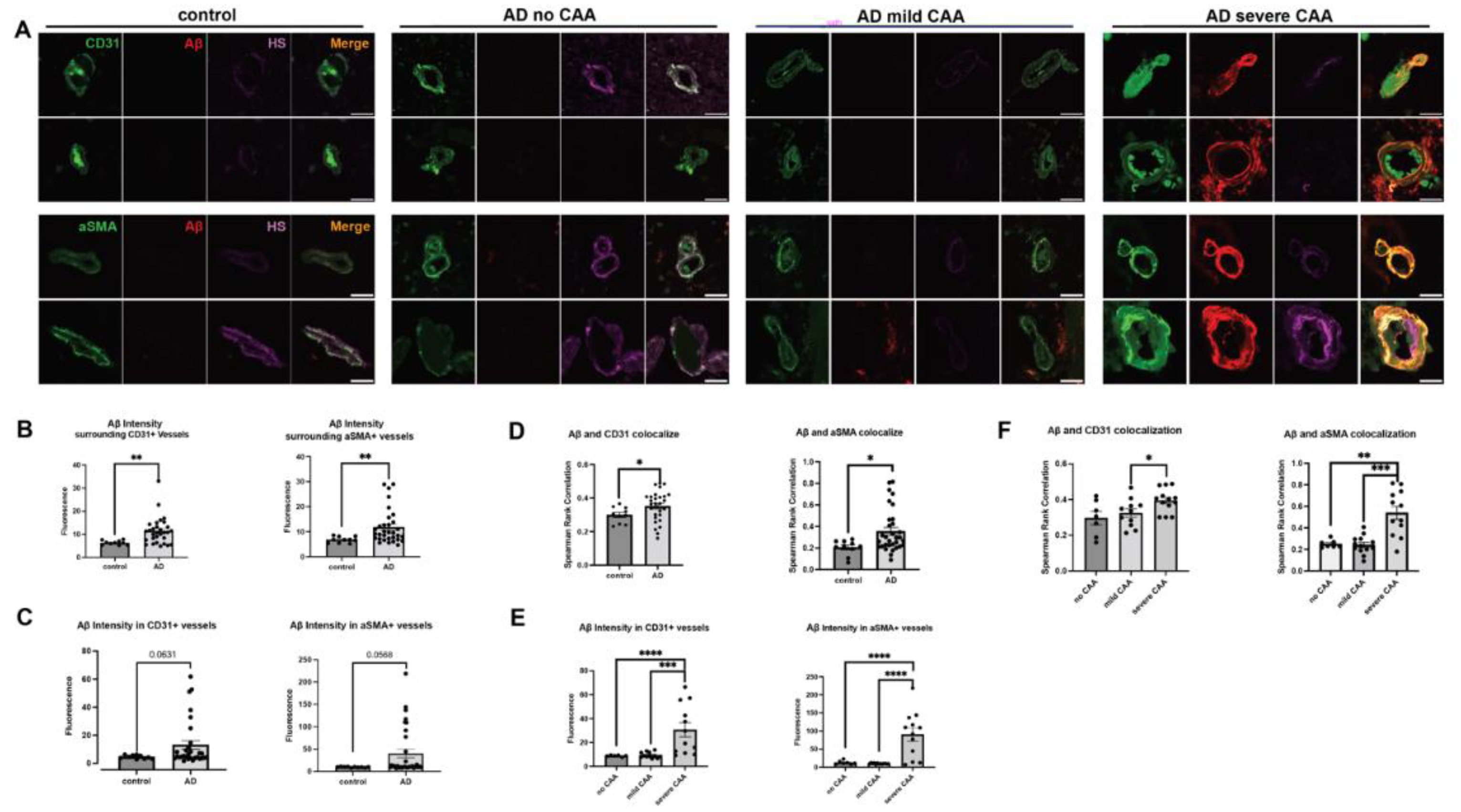

Cerebrovascular Aβ Accumulation in AD Patients Increases with Severe CAA

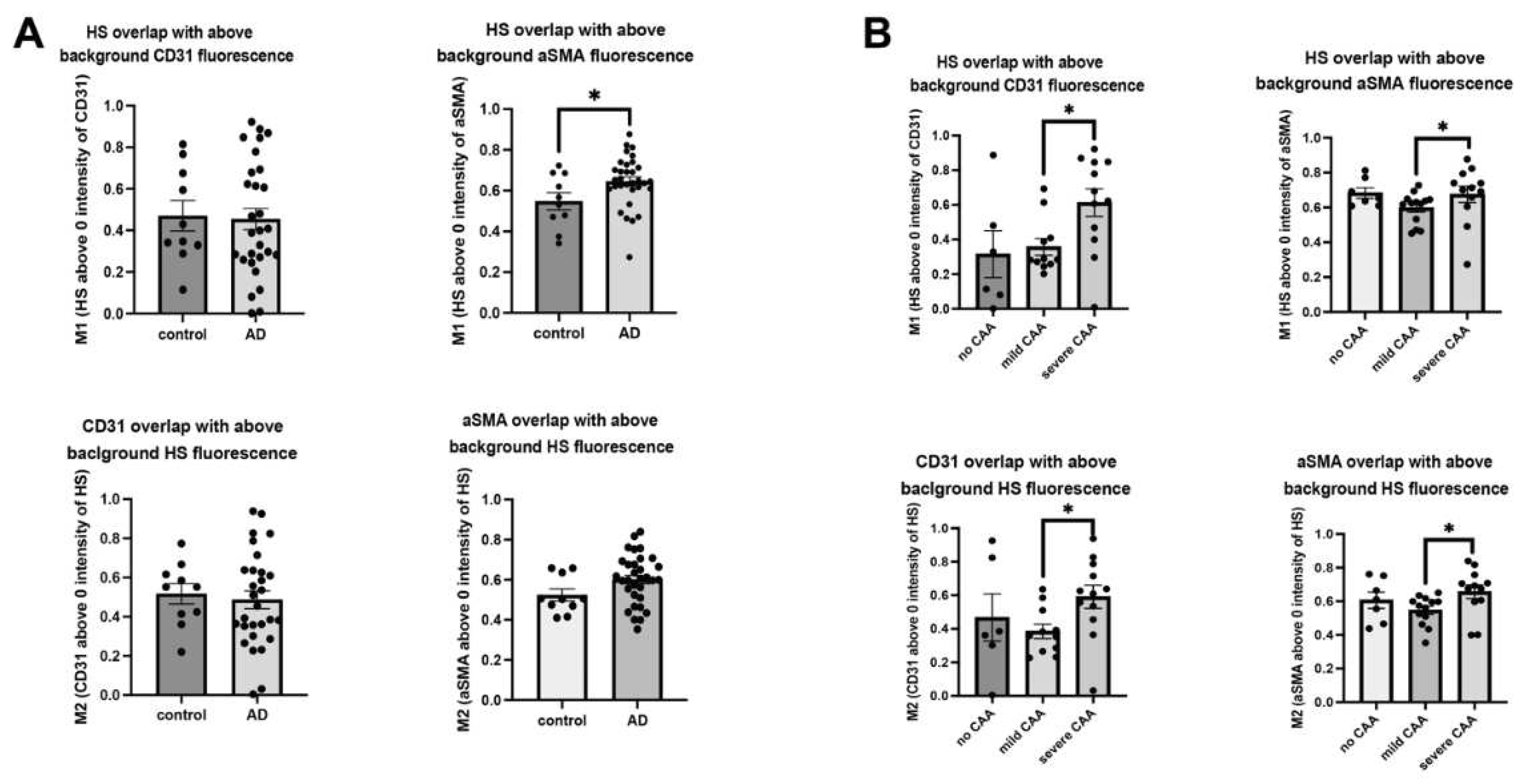

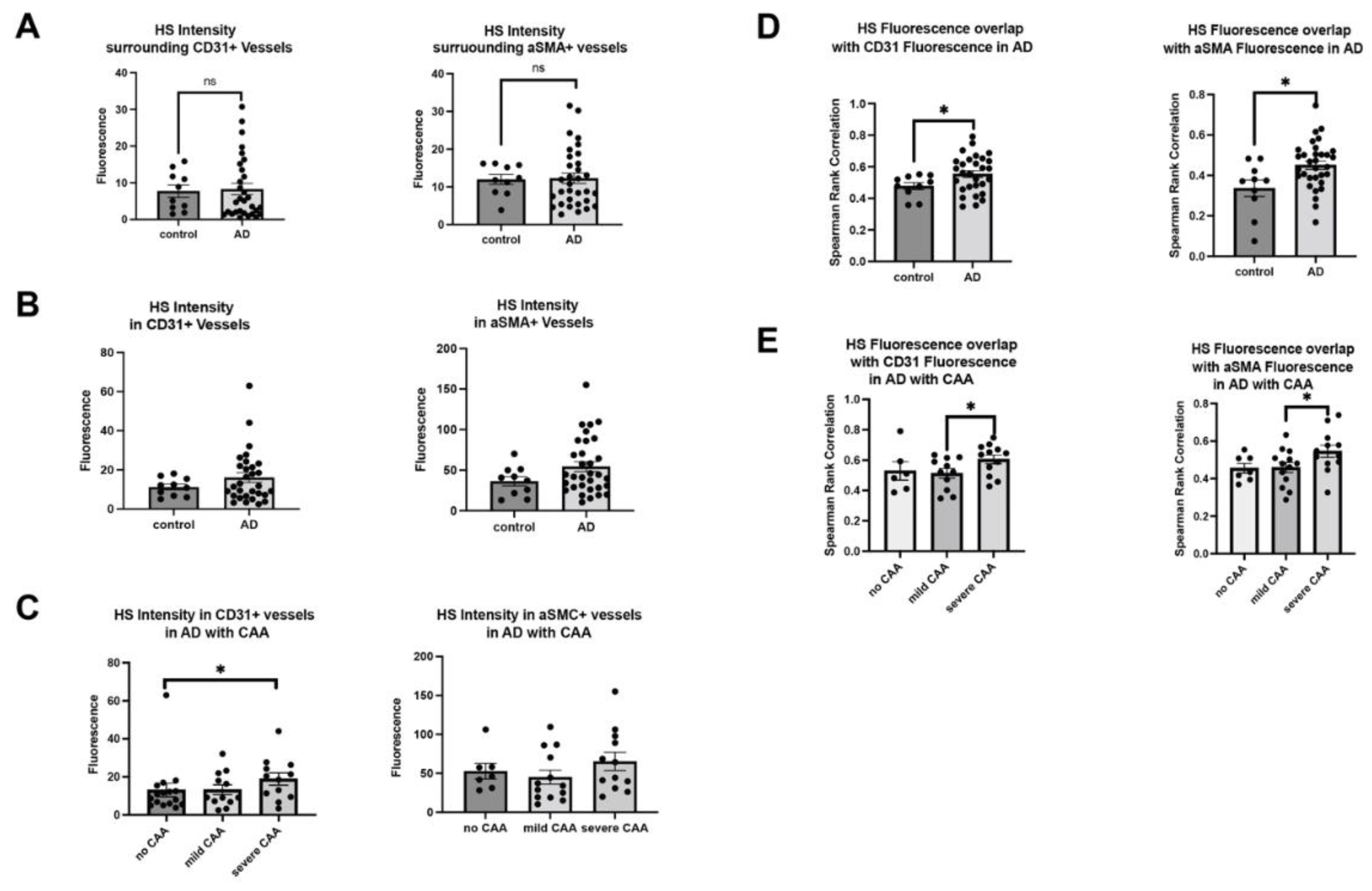

Cerebrovascular HS is Elevated in AD Patients with Severe CAA

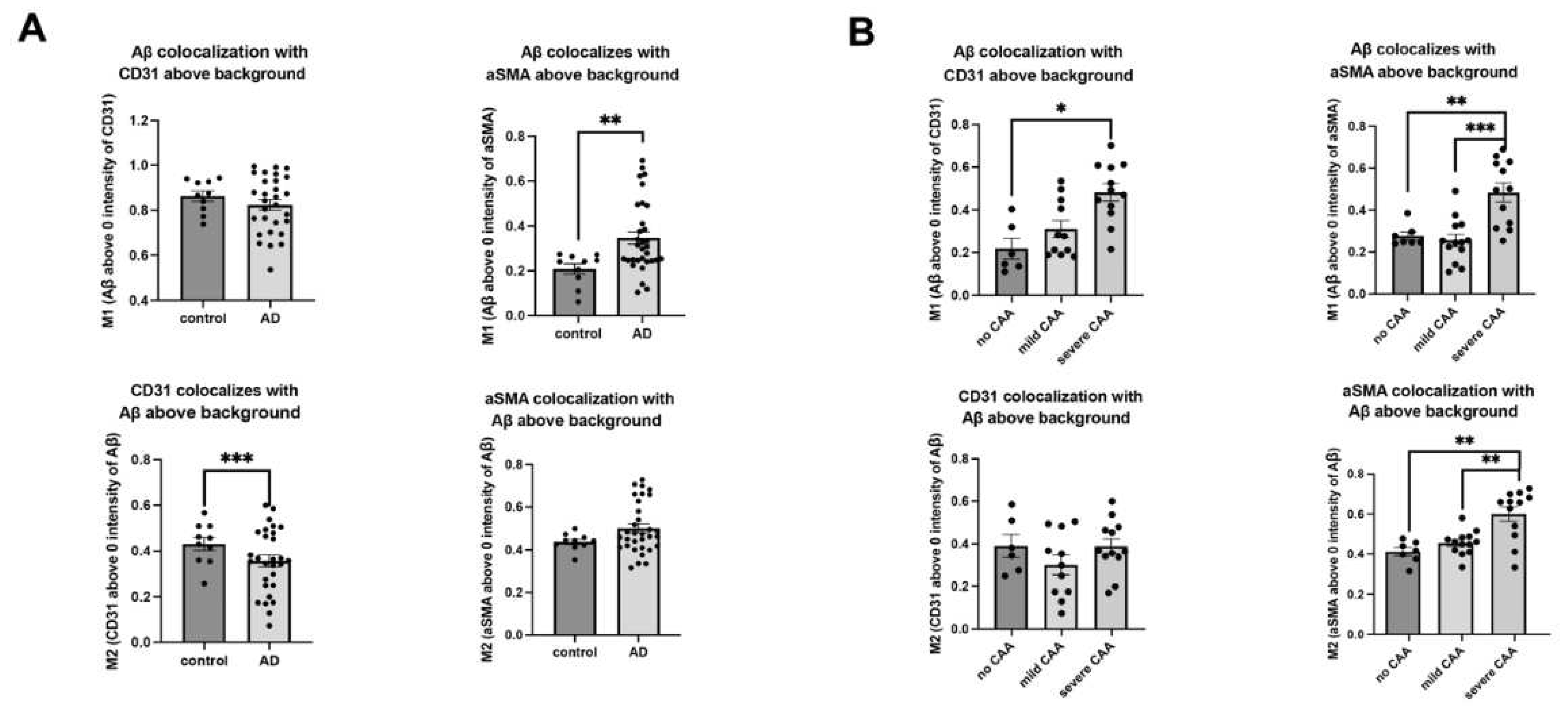

Co-Deposition of Cerebrovascular HS with Aβ is Increased in AD

Polarized HS Expression in Cerebrovasculature is Reversed in AD with Severe CAA While No Polarization of Vascular Aβ Deposition is Observed

Male AD Patients Have Lower Parenchymal and Cerebrovascular HS

ApoE4 Correlates with Elevated Cerebrovascular Aβ and a Tendency of Higher HS Expression in AD

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Human Brain Tissues

Immunofluorescence Staining

Imaging and Image Analyses

Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- De Ture, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keage, H.A.; O Carare, R.; Friedland, R.P.; Ince, P.G.; Love, S.; A Nicoll, J.; Wharton, S.B.; O Weller, R.; Brayne, C. Population studies of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy and dementia: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2009, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäkel, L.; De Kort, A.M.; Klijn, C.J.; Schreuder, F.H.; Verbeek, M.M. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer's Dement. 2021, 18, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dyck, C.H. , et al., Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med, 2023. 388(1): p. 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.M. , et al., Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer disease - one peptide, two pathways. Nat Rev Neurol, 2020. 16(1): p. 30-42. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, C.J. , et al., A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Abeta protofibril antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2021. 13(1): p. 80. [CrossRef]

- Mintun, M.A. , et al., Donanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med, 2021. 384(18): p. 1691-1704. [CrossRef]

- Haeberlein, S.B.; Aisen, P.; Barkhof, F.; Chalkias, S.; Chen, T.; Cohen, S.; Dent, G.; Hansson, O.; Harrison, K.; von Hehn, C.; et al. Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer's Dis. 2022, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevigny, J. , et al., The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature, 2016. 537(7618): p. 50-6. [CrossRef]

- Salloway, S.; Farlow, M.; McDade, E.; Clifford, D.B.; Wang, G.; Llibre-Guerra, J.J.; Hitchcock, J.M.; Mills, S.L.; Santacruz, A.M.; Aschenbrenner, A.J.; et al. A trial of gantenerumab or solanezumab in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, C. Report on trial death stokes Alzheimer’s drug fears. Science 2023, 380, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salloway, S.; Chalkias, S.; Barkhof, F.; Burkett, P.; Barakos, J.; Purcell, D.; Suhy, J.; Forrestal, F.; Tian, Y.; Umans, K.; et al. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in 2 Phase 3 Studies Evaluating Aducanumab in Patients With Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withington, C.G.; Turner, R.S. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities With Anti-amyloid Antibodies for the Treatment of Dementia Due to Alzheimer's Disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 862369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M. , et al., Impact of Anti-amyloid-beta Monoclonal Antibodies on the Pathology and Clinical Profile of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Aducanumab and Lecanemab. Front Aging Neurosci, 2022. 14: p. 870517. [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, S., W. C. Lamanna, and J.D. Esko, Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2011. 3(7). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Shi, S.; Yue, J.; Xin, M.; Nairn, A.V.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Li, G.; Archer-Hartmann, S.A.; Rosa, M.D.; et al. A mutant-cell library for systematic analysis of heparan sulfate structure–function relationships. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.R.; Schuksz, M.; Esko, J.D. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature 2007, 446, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P. and M. Kusche-Gullberg, Heparan Sulfate: Biosynthesis, Structure, and Function. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol, 2016. 325: p. 215-73. [CrossRef]

- Kraushaar, D.C.; Rai, S.; Condac, E.; Nairn, A.; Zhang, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Moremen, K.; Dalton, S.; Wang, L. Heparan sulfate facilitates FGF and BMP signaling to drive mesoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 22691–22700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Xiao, W.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, F.; Moniz, H.A.; Jaworski, A.; Condac, E.; Gutierrez-Sanchez, G.; Heiss, C.; Clugston, R.D.; et al. Heparan sulfate deficiency disrupts developmental angiogenesis and causes congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 124, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S. , et al., Heparan sulfate inhibits transforming growth factor beta signaling and functions in cis and in trans to regulate prostate stem/progenitor cell activities. Glycobiology, 2020. 30(6): p. 381-395. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fuster, M.; Sriramarao, P.; Esko, J.D. Endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency impairs L-selectin- and chemokine-mediated neutrophil trafficking during inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talsma, D.T.; Katta, K.; Ettema, M.A.B.; Kel, B.; Kusche-Gullberg, M.; Daha, M.R.; Stegeman, C.A.; van den Born, J.; Wang, L. Endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency reduces inflammation and fibrosis in murine diabetic nephropathy. Lab. Investig. 2018, 98, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H. , et al., Interaction between beta-amyloid protein and heparan sulfate proteoglycans from the cerebral capillary basement membrane in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Neurosci, 2009. 16(2): p. 277-82. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, M.B.; Ouidja, M.O.; Chantepie, S.; Carpentier, G.; Maïza, A.; Zhang, G.; Vilares, J.; Raisman-Vozari, R.; Papy-Garcia, D. Glycosaminoglycans from Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus have altered capacities to bind and regulate growth factors activities and to bind tau. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0209573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono-Fukao, T.; Ohtake-Niimi, S.; Nishitsuji, K.; Hossain, M.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Michikawa, M.; Uchimura, K. RB4CD12 epitope expression and heparan sulfate disaccharide composition in brain vasculature. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011, 89, 1840–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, A.D.; Lara, S.; Nochlin, D.; Wight, T.N. Cationic dyes reveal proteoglycans structurally integrated within the characteristic lesions of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1989, 78, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, A.D.; Mar, H.; Nochlin, D.; Kimata, K.; Kato, M.; Suzuki, S.; Hassell, J.; Wight, T.N. The presence of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the neuritic plaques and congophilic angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1988, 133, 456–63. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, A.D. , et al., Early accumulation of heparan sulfate in neurons and in the beta-amyloid protein-containing lesions of Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome. Am J Pathol, 1990. 137(5): p. 1253-70.

- Snow, A.D.; Sekiguchi, R.T.; Nochlin, D.; Kalaria, R.N.; Kimata, K. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan in diffuse plaques of hippocampus but not of cerebellum in Alzheimer's disease brain. Am. J. Pathol. 1994, 144, 337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, A.D.; Wight, T.N. Proteoglycans in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and other amyloidoses. Neurobiol. Aging 1989, 10, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Hebisch, M.; Sliwinski, C.; Lee, S.; D’avanzo, C.; Chen, H.; Hooli, B.; Asselin, C.; Muffat, J.; et al. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2014, 515, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsan McMillan, I., J. P. Li, and L. Wang, Heparan sulfate proteoglycan in Alzheimer’s disease: aberrant expression and functions in molecular pathways related to amyloid-beta metabolism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2023. 324(4): p. C893-C909. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. , Gandy,L., Zhang, F., Liu, J., Wang, C., Blair, L. J., Linhardt, R. J., Wang, L., Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Tauopathy Biomolecules 2022. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B. , et al., Common binding sites for beta-amyloid fibrils and fibroblast growth factor-2 in heparan sulfate from human cerebral cortex. J Biol Chem, 1999. 274(43): p. 30631-5. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H. , et al., Size and sulfation are critical for the effect of heparin on APP processing and Abeta production. J Neurochem, 2012. 123(3): p. 447-57. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.J., A. D. Lander, and D.J. Selkoe, Heparin-binding properties of the amyloidogenic peptides Abeta and amylin. Dependence on aggregation state and inhibition by Congo red. J Biol Chem, 1997. 272(50): p. 31617-24. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, G.M. , et al., The sulfate moieties of glycosaminoglycans are critical for the enhancement of beta-amyloid protein fibril formation. J Neurochem, 1999. 72(4): p. 1681-7. [CrossRef]

- Perry, G.; Siedlak, S.; Richey, P.; Kawai, M.; Cras, P.; Kalaria, R.N.; Galloway, P.; Scardina, J.; Cordell, B.; Greenberg, B. Association of heparan sulfate proteoglycan with the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 1991, 11, 3679–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, L.S.; Chui, H.C.; Saperia, D.; Athanikar, J. Microangiopathy and the colocalization of heparan sulfate proteoglycan with amyloid in senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 1990, 508, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwall, E.; O'Callaghan, P.; Zhang, X.; Lindahl, U.; Lannfelt, L.; Li, J.-P. Heparan sulfate mediates amyloid-beta internalization and cytotoxicity. Glycobiology 2010, 20, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, K. , et al., Cellular interaction and cytotoxicity of the iowa mutation of apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-IIowa) amyloid mediated by sulfate moieties of heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem, 2015. 290(40): p. 24210-21. [CrossRef]

- Stopschinski, B.E. , et al., Specific glycosaminoglycan chain length and sulfation patterns are required for cell uptake of tau versus alpha-synuclein and beta-amyloid aggregates. J Biol Chem, 2018. 293(27): p. 10826-10840. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sanderson, R.D. Heparanase Regulates Levels of Syndecan-1 in the Nucleus. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.M. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 Infection Depends on Cellular Heparan Sulfate and ACE2. Cell, 2020. 183(4): p. 1043-1057 e15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. , et al., Heparanase overexpression impairs inflammatory response and macrophage-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta in murine brain. Acta Neuropathol, 2012. 124(4): p. 465-78. [CrossRef]

- Jendresen, C.B. , et al., Overexpression of heparanase lowers the amyloid burden in amyloid-beta precursor protein transgenic mice. J Biol Chem, 2015. 290(8): p. 5053-64. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C. , et al., Neuronal heparan sulfates promote amyloid pathology by modulating brain amyloid-beta clearance and aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med, 2016. 8(332): p. 332ra44. [CrossRef]

- Stoler-Barak, L.; Moussion, C.; Shezen, E.; Hatzav, M.; Sixt, M.; Alon, R. Blood vessels pattern heparan sulfate gradients between their apical and basolateral aspects. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e85699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijmer, Y.D.; Fotiadis, P.; Riley, G.A.; Xiong, L.; Charidimou, A.; Boulouis, G.; Ayres, A.M.; Schwab, K.; Rosand, J.; Gurol, M.E.; et al. Progression of Brain Network Alterations in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Stroke 2016, 47, 2470–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C. , et al., Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol, 2013. 9(2): p. 106-18. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.F.; Mormino, E.C.; Rabin, J.S.; Hohman, T.J.; Landau, S.; Hanseeuw, B.J.; Jacobs, H.I.L.; Papp, K.V.; Amariglio, R.E.; Properzi, M.J.; et al. Sex Differences in the Association of Global Amyloid and Regional Tau Deposition Measured by Positron Emission Tomography in Clinically Normal Older Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P.T. , et al., APOE-epsilon2 and APOE-epsilon4 correlate with increased amyloid accumulation in cerebral vasculature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2013. 72(7): p. 708-15. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Deguchi, N.; Takagi, C.; Tanaka, M.; Dhanasekaran, P.; Nakano, M.; Handa, T.; Phillips, M.C.; Lund-Katz, S.; Saito, H. Role of the N- and C-terminal domains in binding of apolipoprotein E isoforms to heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate: a surface plasmon resonance study. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 6702–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y. , et al., Apolipoprotein E lipoprotein particles inhibit amyloid-beta uptake through cell surface heparan sulphate proteoglycan. Mol Neurodegener, 2016. 11(1): p. 37. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.M. , et al., Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 and cerebral hemorrhage associated with amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol, 1995. 38(2): p. 254-9. [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Black, S.E.; Frosch, M.P.; Greenberg, S.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Scheltens, P.; Carrillo, M.C.; Thies, W.; Bednar, M.M.; et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: Recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2011, 7, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakuda, N. , et al., Distinct deposition of amyloid-beta species in brains with Alzheimer’s disease pathology visualized with MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 2017. 5(1): p. 73. [CrossRef]

- Gravina, S.A. , et al., Amyloid beta protein (A beta) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at A beta 40 or A beta 42(43). J Biol Chem, 1995. 270(13): p. 7013-6. [CrossRef]

- E Roher, A.; Lowenson, J.D.; Clarke, S.; Woods, A.S.; Cotter, R.J.; Gowing, E.; Ball, M.J. beta-Amyloid-(1-42) is a major component of cerebrovascular amyloid deposits: implications for the pathology of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10836–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.; Papayannopoulos, I.; Styles, J.; Bobin, S.; Lin, Y.; Biemann, K.; Iqbal, K. Peptide compositions of the cerebrovascular and senile plaque core amyloid deposits of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 301, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Arnold, K.; Dhurandahare, V.M.; Xu, Y.; Pagadala, V.; Labra, E.; Jeske, W.; Fareed, J.; Gearing, M.; Liu, J. Analysis of 3-O-Sulfated Heparan Sulfate Using Isotopically Labeled Oligosaccharide Calibrants. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2950–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. , et al., Increased 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in Alzheimer’s disease brain is associated with genetic risk gene HS3ST1. Sci Adv, 2023. 9(21): p. eadf6232. [CrossRef]

- Madine, J. , et al., Site-specific identification of an abeta fibril-heparin interaction site by using solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2012. 51(52): p. 13140-3. [CrossRef]

- Madine, J. , et al., Exploiting a (13)C-labelled heparin analogue for in situ solid-state NMR investigations of peptide-glycan interactions within amyloid fibrils. Org Biomol Chem, 2009. 7(11): p. 2414-20. [CrossRef]

- Snow, A.D.; Cummings, J.A.; Lake, T. The Unifying Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans/Glycosaminoglycans Are Key as First Hypothesized Over 30 Years Ago. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 710683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasoff-Conway, J.M.; Carare, R.O.; Osorio, R.S.; Glodzik, L.; Butler, T.; Fieremans, E.; Axel, L.; Rusinek, H.; Nicholson, C.; Zlokovic, B.V.; et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carare, R.O.; Bernardes-Silva, M.; Newman, T.A.; Page, A.M.; Nicoll, J.A.R.; Perry, V.H.; Weller, R.O. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2008, 34, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albargothy, N.J.; Johnston, D.A.; Sharp, M.M.; Weller, R.O.; Verma, A.; Hawkes, C.A.; Carare, R.O. Convective influx/glymphatic system: tracers injected into the CSF enter and leave the brain along separate periarterial basement membrane pathways. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keable, A. , et al., Deposition of amyloid beta in the walls of human leptomeningeal arteries in relation to perivascular drainage pathways in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016. 1862(5): p. 1037-46. [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.; Leong, D.F.M.; Lee, J.J.L.; Cool, S.M.; Nurcombe, V. Comparative Assessment of the Effects of Gender-specific Heparan Sulfates on Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17755–17765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasnovas, J.; Damron, C.L.; Jarrell, J.; Orr, K.S.; Bone, R.N.; Archer-Hartmann, S.; Azadi, P.; Kua, K.L. Offspring of Obese Dams Exhibit Sex-Differences in Pancreatic Heparan Sulfate Glycosaminoglycans and Islet Insulin Secretion. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 658439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, I.; Noguchi, N.; Nata, K.; Yamada, S.; Kaneiwa, T.; Mizumoto, S.; Ikeda, T.; Sugihara, K.; Asano, M.; Yoshikawa, T.; et al. Important role of heparan sulfate in postnatal islet growth and insulin secretion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 383, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, F.; Persaud, A.; Zaokari, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, D. Vascular Dementia and Underlying Sex Differences. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 720715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, A.M. , et al., Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 1993. 43(8): p. 1467-72. [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, G.W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Farrer, L.; A Cupples, L.; Haines, J.L.; Hyman, B.; A Kukull, W.; Mayeux, R.; Myers, R.H.; A Pericak-Vance, M.; Risch, N.; Van Duijn, C.M. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA 1997, 278, 1349–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, E.; Haikonen, S.; Luoto, T.; Huhtala, H.; Goebeler, S.; Haapasalo, H.; Karhunen, P.J. Apolipoprotein E–dependent accumulation of Alzheimer disease–related lesions begins in middle age. Ann. Neurol. 2009, 65, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C. , et al., APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol, 2010. 67(1): p. 122-31.

- Hawkes, C.A. , et al., Disruption of arterial perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the brains of mice expressing the human APOE epsilon4 allele. PLoS One, 2012. 7(7): p. e41636. [CrossRef]

- Robert, J. , et al., Clearance of beta-amyloid is facilitated by apolipoprotein E and circulating high-density lipoproteins in bioengineered human vessels. Elife, 2017. 6. [CrossRef]

- DeMattos, R.B. , et al., ApoE and clusterin cooperatively suppress Abeta levels and deposition: evidence that ApoE regulates extracellular Abeta metabolism in vivo. Neuron, 2004. 41(2): p. 193-202. [CrossRef]

- Kanekiyo, T. and G. Bu, The low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 and amyloid-beta clearance in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci, 2014. 6: p. 93. [CrossRef]

- Mawuenyega, K.G. , et al., Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science, 2010. 330(6012): p. 1774. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Rusinek, H.; Butler, T.; Glodzik, L.; Pirraglia, E.; Babich, J.; Mozley, P.D.; Nehmeh, S.; Pahlajani, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Decreased CSF clearance and increased brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient diagnosis | Total number | Gender (M/F) | Age at Death (Ave ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None AD | 10 | 4/6 | 71.00 ± 5.62 |

| AD, no CAA | 7 | 3/4 | 76.43 ± 3.24 |

| AD, mild CAA | 12 | 7/5 | 76.46 ± 3.43 |

| AD, severe CAA | 12 | 7/5 | 77.75 ± 2.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).