Submitted:

08 February 2024

Posted:

09 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

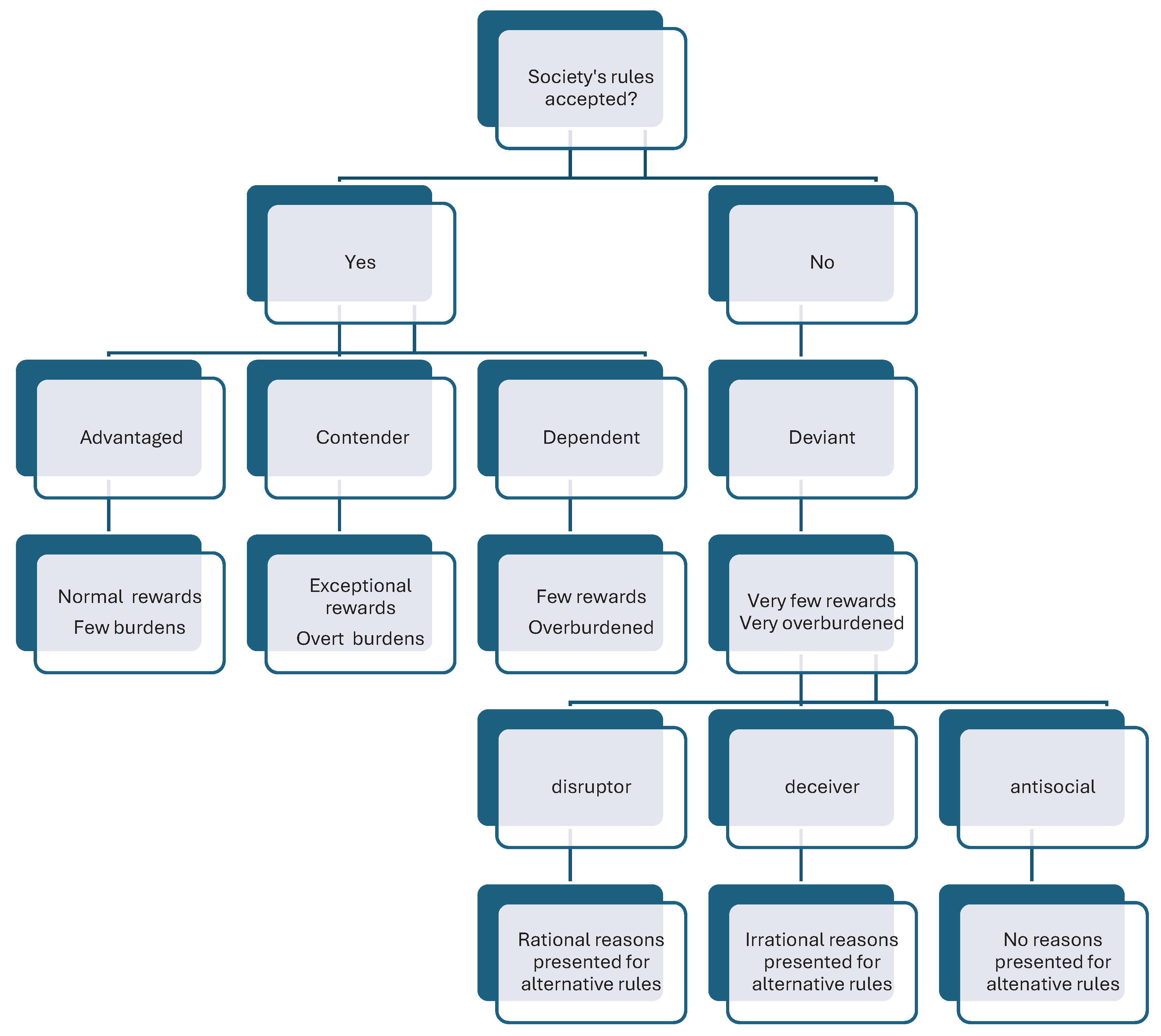

1. Introduction

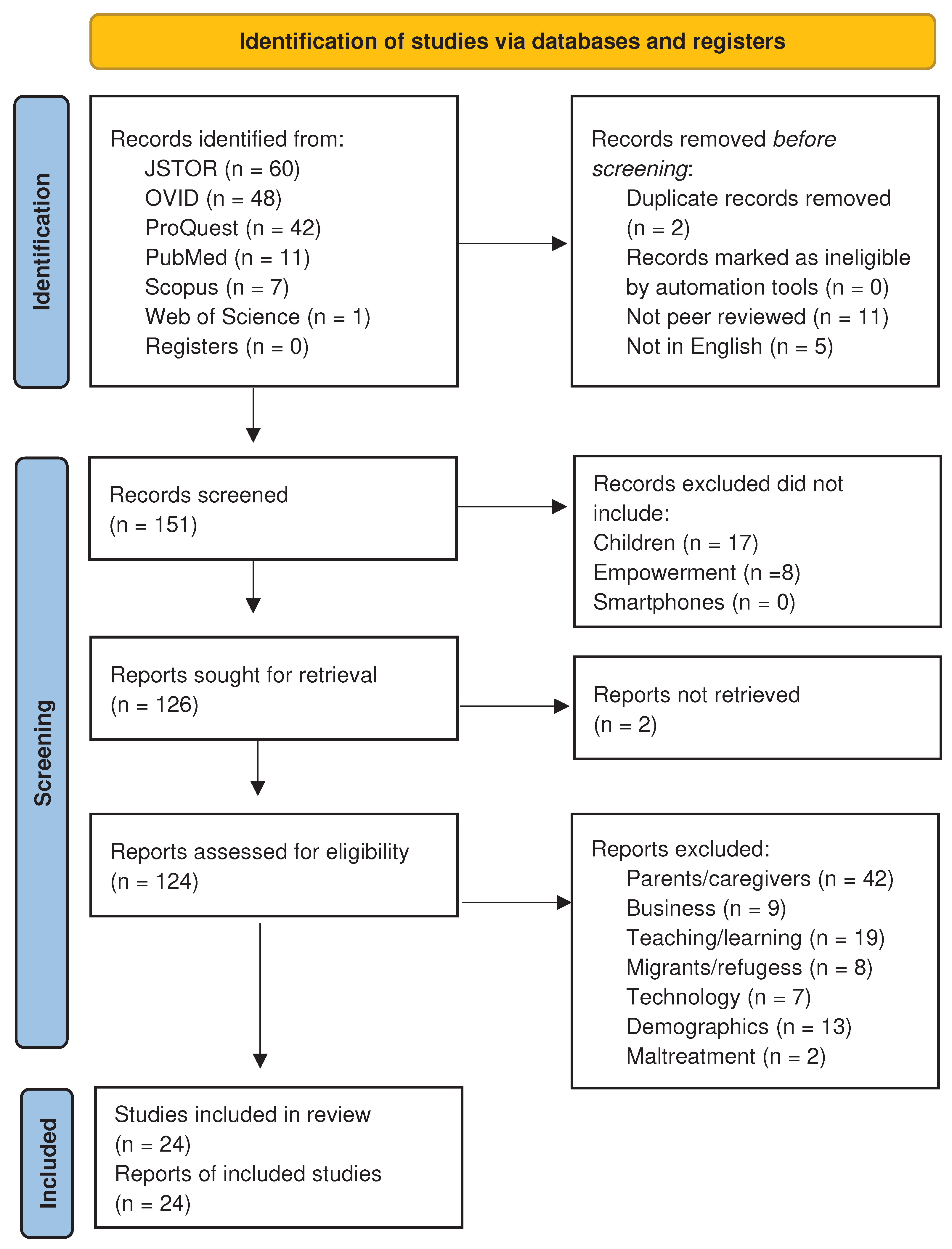

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Details of the Individual Searches

3. Results

3.1. Dependents

3.2. Advantaged

3.3. Contenders

3.4. Deviants

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of the Scoping Review

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schneider, A.; Ingram, H. Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy. Amer Polit Sci Rev 1993, 87, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.; Ingram, H.M. Social Constructions, Anticipatory Feedback Strategies, and Deceptive Public Policy. Policy Stud J 2019, 47, 206–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbehön, M. Reclaiming Constructivism: Towards an Interpretive Reading of the ‘Social Construction Framework. ’ Policy Sci 2020, 53, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, H.; Daramola, E.J.; Marsh, J.A.; Enoch-Stevens, T.; Alonso, J.; Allbright, T.N. Social Construction Is Racial Construction: Examining the Target Populations in School-Choice Policies. Am J Edu 2022, 128, 487–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopster, J. What Are Socially Disruptive Technologies? Techn Soc 2021, 67, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodaghi, A.; Oliveira, J. The Theater of Fake News Spreading, Who Plays Which Role? A Study on Real Graphs of Spreading on Twitter. Expert Sys App 2022, 189, 116110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T. Why Do People Spread False Information Online? The Effects of Message and Viewer Characteristics on Self-Reported Likelihood of Sharing Social Media Disinformation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P. The Integrated Cognitive Antisocial Potential (ICAP) Theory: Past, Present, and Future. J Dev Life Course Criminology 2020, 6, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Moore, R.; Waterman, M. Deconstructing “Sexual Deviance”: Identifying and Empirically Examining Assumptions about “Deviant” Sexual Fantasy in the DSM. J Sex Res 2023, 60, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Q. Property Rights and Theft Wrongs? A Preliminary Analysis of Stealing in the Extractive Industries. Extractive Indus Soc 2023, 15, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Kwon, H.; Park, J.; Hong, H.J.; Kweon, Y.-S. A Latent Class Analysis of Suicidal Behaviors in Adolescents. Psychiatry Investig 2023, 20, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sender, A.; Morf, M.; Feierabend, A. Aiming to Leave and Aiming to Harm: The Role of Turnover Intentions and Job Opportunities for Minor and Serious Deviance. J Bus Psychol 2021, 36, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.J.; Siddiki, S.; Jones, M.D.; Schumacher, K.; Pattison, A.; Peterson, H. Social Construction and Policy Design: A Review of Past Applications. Policy Studies Journal 2014, 42, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.; Ingram, H.M. Policy Design for Democracy; Studies in government and public policy; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- American Political Science Association. Organized Section 4: Aaron Wildavsky Enduring Contribution Award. Available online: https://www.apsanet.org/section-4-aaron-wildavsky-enduring-contribution-award (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Theories of the Policy Process; Theoretical lenses on public policy; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, Colo, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Theories of the Policy Process, 2nd ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, Colo, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Theories of the Policy Process, [new ed., new coll.], 3rd ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Weible, C.M., Eds.; Westview Press: Boulder, Colo, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Theories of the Policy Process; Weible, C.M., Sabatier, P.A., Eds.; 4th ed.; Routledge: Fourth edition. | Westview Press: Boulder, Colo, 2017, 2018.

- Theories of the Policy Process; Weible, C.M., Ed.; Fifth edition.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York London, 2023.

- Srivastava, S. Varieties of Social Construction. Int Stud Rev 2020, 22, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gándara, D.; Jones, S. Who Deserves Benefits in Higher Education? A Policy Discourse Analysis of a Process Surrounding Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. Rev Higher Edu 2020, 44, 121–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson-Crotty, J.; Miller, S.M.; Keiser, L.R. Administrative Burden, Social Construction, and Public Support for Government Programs. JBPA 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochmann, M. Identities, Intersectionality, and Otherness: The Social Constructions of Deservedness in American Housing Policy. Admin Theory Praxis 2021, 43, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.E.; Mead, M. Social Constructions of Children and Youth: Beyond Dependents and Deviants. J Soc Pol 2021, 50, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindacher, V.; Curbach, J.; Warrelmann, B.; Brandstetter, S.; Loss, J. Evaluation of Empowerment in Health Promotion Interventions: A Systematic Review. Eval Health Prof 2018, 41, 351–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friska, D.; Kekalih, A.; Runtu, F.; Rahmawati, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.A.; Anugrapaksi, E.; Utami, N.P.B.S.; Wijaya, A.D.; Ayuningtyas, R. Health Cadres Empowerment Program through Smartphone Application-Based Educational Videos to Promote Child Growth and Development. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 887288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, A. Pioneers of Television — Philo Taylor Farnsworth. J SMPTE 1992, 101, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzkin, P. The Boy Who Invented Television: A Story of Inspiration, Persistence, and Quiet Passion, 1st ed.; TeamCom Books: Silver Spring, MD, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lütkes, L.; Tuitjer, L.; Dirksmeier, P. Sailing to Save the Planet? Media-Produced Narratives of Greta Thunberg’s Trip to the UN Climate Summit in German Print Newspapers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Petkanic, P.; Nan, D.; Kim, J.H. When a Girl Awakened the World: A User and Social Message Analysis of Greta Thunberg. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, N. The Temptation of Performing Cuteness: Shirley Temple’s Birthday Parties during the Great Depression. Feminist Media Studies 2023, 23, 3091–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasson, J.F. The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America, First edition.; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. Subculture Theory: Delinquent Boys. In Criminology theory: selected classic readings; Williams, F.P., McShane, M.D., Eds.; Routledge: London New York, 2016; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, T.J. Subcultural Theories of Crime. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance; Holt, T.J., Bossler, A.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 513–526. [Google Scholar]

- Iuliana, A. Subcultural Theories of Delinquency and Crime. Journal of Law and Administrative Sciences 2021, 16, 135. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/jladsc16&div=14&id=&page= (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Rahman, Md.M. A Theoretical Framework on Juvenile Gang Delinquency: Its Roots and Solutions. BLR 2022, 13, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.P. Disruptive Entrepreneurship and Dual Purpose Strategies: The Case of Uber. Strategy Science 2018, 3, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, A.; Bergemann, P.; Helms, W. Getting Away with It (Or Not): The Social Control of Organizational Deviance. AMR 2023, amr.2021.0066. [CrossRef]

- Al-khateeb, S.; Agarwal, N. Deviance in Social Media. In Deviance in Social Media and Social Cyber Forensics; SpringerBriefs in Cybersecurity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, M. Fake News as an Informational Moral Panic: The Symbolic Deviancy of Social Media during the 2016 US Presidential Election. Information, Communication & Society 2020, 23, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, D.M. The Deception Faucet: A Metaphor to Conceptualize Deception and Its Detection. New Ideas Psychol 2020, 59, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, L. Prostitutes and Their Rescuers: Sociological Dynamics and Public Controversies in French Prostitution; BRILL: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, P.E.; Bolle, F. Power Attitudes and Stealing: Senses of Responsibility. Economics & Sociology 2020, 13, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T. Political Vandalism as Counter-speech: A Defense of Defacing and Destroying Tainted Monuments. European J of Philosophy 2020, 28, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J.R.; Obaidi, M. Understanding Violent Extremism in the 21st Century: The (Re)Emerging Role of Relative Deprivation. Current Opinion in Psychology 2020, 35, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukinen, C. When Stay-at-Home Orders Leave Victims Unsafe at Home: Exploring the Risk and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Crim Just 2020, 45, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, L. Farnsworth. In The Cinema in Flux; Springer US: New York, NY, 2021; pp. 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A.J. Reading Between the Lines. Diplom His 2004, 28, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Diz, P.; Conde-Jiménez, J.; Reyes De Cózar, S. Teens’ Motivations to Spread Fake News on WhatsApp. Social Media Soc 2020, 6, 205630512094287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.Z.; Ling, R. “What Is Computer-Mediated Communication?”—An Introduction to the Special Issue. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2020, 25, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yus, F. Smartphone Communication: Interactions in the App Ecosystem; 1st ed.; Routledge: London, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.; Kim, J.; Shin, J. Does the Improvement of Public Wi-Fi Technology Undermine Mobile Network Operators’ Profits? Evidence from Consumer Preferences. Telematics Informatics 2022, 69, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, B.; Logeshwaran, J; Kiruthiga, T. An Innovation in the Development of a Mobile Radio Model for a Dual-Band Transceiver in Wireless Cellular Communication. BIJCICN 2023, 1, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gao, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, R.; Shang, R. Smartphone Positioning and Accuracy Analysis Based on Real-Time Regional Ionospheric Correction Model. Sensors 2021, 21, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buabbas, A.; Hasan, H.; Shehab, A.A. Parents’ Attitudes Toward School Students’ Overuse of Smartphones and Its Detrimental Health Impacts: Qualitative Study. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2021, 4, e24196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J.; Allen, N. Scrutinizing the Effects of Digital Technology on Mental Health. Nature 2020, 578, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, H.K.; Choi, J.-S.; Bang, S.; Park, M.-H.; Jung, K.-I.; Kweon, Y.-S. The Matthew Effect in Recovery from Smartphone Addiction in a 6-Month Longitudinal Study of Children and Adolescents. IJERPH 2020, 17, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Amri, A.; Abdulaziz, S.; Bashir, S.; Ahsan, M.; Abualait, T. Effects of Smartphone Addiction on Cognitive Function and Physical Activity in Middle-School Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1182749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Hao, J.; Su, L.; Wang, T.; Du, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y. How Parental Smartphone Addiction Affects Adolescent Smartphone Addiction: The Effect of the Parent-Child Relationship and Parental Bonding. J Affect Dis 2022, 307, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, I.B.; Lee, S. How Does Parental Smartphone Addiction Affect Adolescent Smartphone Addiction? Testing the Mediating Roles of Parental Rejection and Adolescent Depression. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Networking 2021, 24, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeng, S. Self-Directed Learning: A Core Concept in Adult Education. Educ Res Int 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, J. Personal Values and Mortality: Power, Benevolence and Self-Direction Predict Mortality Risk. Psychol Health 2021, 36, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Chakraborty, P. Child–Smartphone Interaction: Relevance and Positive and Negative Implications. Univ Access Inf Soc 2022, 21, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, A. The Preference for Self-Direction as a Resource for Parents’ Socialisation Practices. Qual Res Psychol 2020, 17, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mone, I.-S.; Benga, O. The Relationship between Education, Agency, and Socialization Goals in a Sample of Mothers of Preschoolers. J Fam Stud 2022, 28, 1074–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskam, I.; Aguiar, J.; Akgun, E.; Arena, A.F.; Arikan, G.; Aunola, K.; Besson, E.; Beyers, W.; Boujut, E.; Brianda, M.E.; et al. Three Reasons Why Parental Burnout Is More Prevalent in Individualistic Countries: A Mediation Study in 36 Countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E.; Weisman, M.B.; Knafo-Noam, A.; Bardi, A. Longitudinal Links Between Self-Esteem and the Importance of Self-Direction Values During Adolescence. Eur J Pers 2023, 37, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Mikolajczak, M.; Roskam, I. The Cult of the Child: A Critical Examination of Its Consequences on Parents, Teachers and Children. Soc Sci 2022, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int J Consumer Studies 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, S.; Curran, T. Disability Rights and Robotics. Int J Disabil Soc Just 2023, 3, 26–48. Available online: https://www-jstor-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/stable/48752336 (accessed on 3 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zdrodowska, M. Prosthetic Performances: Artistic Strategies, and Tactics for Everyday Life. Icon 2021, 26, 125–146. Available online: https://www-jstor-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/stable/27120658 (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Richens, R.C. Privacy in a Pandemic: An Examination of the United States’ Response to Covid-19 Analyzing Privacy Rights Afforded to Children Under International Law. Willamette J Int Law Dis Resol 2021, 28, 244–290. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.C.; Walker, K.L.; Kees, J. Children and Online Privacy Protection: Empowerment from Cognitive Defense Strategies. J Public Poli Market 2020, 39, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, R. Digital Hyperconnectivity and the Self. Theor Soc 2020, 49, 771–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, R.L.; Binder, S.B.; Greer, A. Unseen Potential: Photovoice Methods in Hazard and Disaster Science. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.V.; Arvidsen, J. Left to Their Own Devices? A Mixed Methods Study Exploring the Impacts of Smartphone Use on Children’s Outdoor Experiences. IJERPH 2021, 18, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Nagaraj, S.; Daniel, R.; Flood, C.; Kulik, D.; Flook, R.; Goldenberg, A.; Brudno, M.; Stedman, I. The Promises and Challenges of Clinical AI in Community Paediatric Medicine. Paedi Child Health 2023, 28, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau-Zhu, A.; Anderson, C.; Lister, M. Assessment of Digital Risks in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services: A Mixed-Method, Theory-Driven Study of Clinicians’ Experiences and Perspectives. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alvarenga, K.A.F.; De Alcântara, W.L.; De Miranda, D.M. What Has Been Done to Improve Learning for Intellectual Disability? An Umbrella Review of Published Meta-analyses and Systematic Reviews. Res Intellect Disabil 2023, 36, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimenäs, S.L.; Östberg, A.; Lundin, M.; Lundgren, J.; Abrahamsson, K.H. Adolescents’ Experiences of a Theory-based Behavioural Intervention for Improved Oral Hygiene: A Qualitative Interview Study. Int J Dental Hygiene 2022, 20, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vameghi, M.; Eftekhari, M.; Falahat, K.; Forouzan, A. Iranian Nongovernmental Organizations’ Initiatives in COVID-19 Pandemic. J Edu Health Promot 2022, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, C.M.; Hutson, E.; Arcoleo, K.; Melnyk, B. Considerations in Pediatric Intervention Research: Lessons Learned from Two Pediatric Pilot Studies. J Pediat Nurs 2022, 63, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, A.; Pikkarainen, M.; Miettunen, J.; He, H.; Pölkki, T. The Effectiveness of Web-based Mobile Health Interventions in Paediatric Outpatient Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Advan Nurs 2020, 76, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, J.; Ekberg, J.; Timpka, T.; Haggren Råsberg, L.; Sjöberg, M.; Mirkovic, D.; Nilsson, S. Developing Web-based Health Guidance for Coaches and Parents in Child Athletics (Track and Field). Scandinavian Med Sci Sports 2020, 30, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.; Martinho, R.; Reis, C.I.; Dias, S.S.; Gaspar, P.J.S.; Dixe, M.D.A.; Luis, L.S.; Ferreira, R. Controlled Trial of an mHealth Intervention to Promote Healthy Behaviours in Adolescence (TeenPower): Effectiveness Analysis. J Adv Nurs 2020, 76, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Dobias, M.; Sung, J.; Mumper, E.; Mullarkey, M.C. Acceptability and Utility of an Open-Access, Online Single-Session Intervention Platform for Adolescent Mental Health. JMIR Ment Health 2020, 7, e20513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Barón, J.; González-Cabrera, J.; Machimbarrena, J.M.; Montiel, I. Safety.Net: A Pilot Study on a Multi-Risk Internet Prevention Program. IJERPH 2021, 18, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abasi, S.; Yazdani, A.; Kiani, S.; Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb, Z. Effectiveness of Mobile Health-based Self-management Application for Posttransplant Cares: A Systematic Review. Health Sci Rep 2021, 4, e434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wihak, T.; Burns, M.; Miranda, J.; Windmueller, G.; Oakley, C.; Coakley, R. Development and Feasibility Testing of the Comfort Ability Program for Sickle Cell Pain: A Patient-Informed, Video-Based Pain Management Intervention for Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. Clin Pract Pediat Psychol 2020, 8, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.K.; McMichael, A.; Rivera-Santana, M.; Noel, J.; Hershey, T. Technological Ecological Momentary Assessment Tools to Study Type 1 Diabetes in Youth: Viewpoint of Methodologies. JMIR Diabetes 2021, 6, e27027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInroy, L.B.; Craig, S.L. “It’s like a Safe Haven Fantasy World”: Online Fandom Communities and the Identity Development Activities of Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. Psychol Pop Media 2020, 9, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cance, J.D.; Adams, E.T.; D’Amico, E.J.; Palimaru, A.; Fernandes, C.S.F.; Fiellin, L.E.; Bonar, E.E.; Walton, M.A.; Komro, K.A.; Knight, D.; et al. Leveraging the Full Continuum of Care to Prevent Opioid Use Disorder. Prev Sci 2023, 24, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedera, K.; Somaiah, B.C.; Yeoh, B.S.A. Growing Up with Smartphones: How Stay-behind Filipino and Indonesian Children Exercise Agency in Transnational Families. Transfers 2022, 12, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Jeong, Y.; Suh, B.; Gweon, G. Is Smartphone Addiction Different from Internet Addiction? Comparison of Addiction-Risk Factors among Adolescents. Behav Infor Techn 2020, 39, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Yee, J.; Chung, J.E.; Kim, H.J.; Han, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.E.; Gwak, H.S. Smartphone Addiction and Anxiety in Adolescents – A Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Health Behav 2021, 45, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panova, T.; Carbonell, X. Is Smartphone Addiction Really an Addiction? J Behav Addict 2018, 7, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaterlaus, J.M.; Aylward, A.; Tarabochia, D.; Martin, J.D. “A Smartphone Made My Life Easier”: An Exploratory Study on Age of Adolescent Smartphone Acquisition and Well-Being. Comput Human Behav 2021, 114, 106563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On My Own: Acquiring Technical Digital Skills for Mobile Phone Use in Chile. Parents-Children Perceptions. Int J Media Infor Lit 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Tso, W.W.Y.; Reichert, F.; Law, N.; Fu, K.W.; De La Torre, J.; Rao, N.; Leung, L.K.; Wang, Y.-L.; Wong, W.H.S.; Ip, P. Digital Competence as a Protective Factor against Gaming Addiction in Children and Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Hong Kong. Lancet 2022, 20, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res Syn Meth 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Glassner, S. Impacts of Low Self-Control and Opportunity Structure on Cyberbullying Developmental Trajectories: Using a Latent Class Growth Analysis. Crime Delinq 2021, 67, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, S. Scrolling and the In-Between Spaces of Boredom: Marginalized Youths on the Periphery of Vienna. Ethos 2020, 48, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, C.S. Cyberbullying Victimization and Perpetration in South Korean Youth: Structural Equation Modeling and Latent Means Analysis. Crime Delinq 2023, 00111287231193992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Moon, S.-H. Predictors for Runaway Behavior in Adolescents in South Korea: National Data from a Comprehensive Survey of Adolescents. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1195378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Han, Y. Associations Between Parental Maltreatment and Online Behavior Among Young Adolescents. J Child Fam Stud 2021, 30, 2782–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, P.; Raghavan, V. Understanding Deviance from the Perspectives of Youth Labelled as Children in Conflict with Law in Mumbai, India. Howard J Crime Justice 2023, 62, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.; Mahanta, R. Smartphone Addiction Culminating into Youth Deviance: A Sociological Study. Intl J Soc Edu 2022, 1, 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, F. The Digital Divide in the US Criminal Justice System. New Media Soc 2022, 24, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.-G.; Cho, H.J.; Jeong, K.-H. The Effects of Korean Parents’ Smartphone Addiction on Korean Children’s Smartphone Addiction: Moderating Effects of Children’s Gender and Age. IJERPH 2021, 18, 6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, T.; Cale, J.; Brewer, R.; Logos, K.; Holt, T.J.; Goldsmith, A. Exploring the Role of Self-Control Across Distinct Patterns of Cyber-Deviance in Emerging Adolescence. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2024, 0306624X231220011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoga Ratnam, K.K.; Nik Farid, N.D.; Wong, L.P.; Yakub, N.A.; Abd Hamid, M.A.I.; Dahlui, M. Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance: A Qualitative Study of Institutionalized Adolescents in Malaysia. Adoles 2022, 2, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, L.S.; Bakar, H.A.; Connaughton, S.L. Understanding Workplace Culture in Malaysia: Cultural Characteristics of Chinese-Malaysian Ethnic Society. IJBG 2023, 34, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensmeier, D.; Lu, Y.; Kumar, S. Age–Crime Relation in India: Similarity or Divergence Vs. Hirschi/Gottfredson Inverted J-Shaped Projection? Brit J Criminol 2019, 59, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensmeier, D.; Lu, Y.; Na, C. Age and Crime in South Korea: Cross-National Challenge to Invariance Thesis. Just Quart 2020, 37, 410–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M. Social Change, Cohort Effects, and Dynamics of the Age–Crime Relationship: Age and Crime in South Korea from 1967 to 2011. J Quant Criminol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y. Values Change and Support for Democracy in East Asia. Soc Indic Res 2022, 160, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L. Confident, Capable and World Changing: Teenagers and Digital Citizenship. Comm Res Pract 2020, 6, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, S.; Lam, L.; Evans, R.; Zhu, C. Cyberbullying Definitions and Measurements in Children and Adolescents: Summarizing 20 Years of Global Efforts. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1000504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, J. The Impatient Gaze: On the Phenomenon of Scrolling in the Age of Boredom. Semiotica 2023, 2023, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Segovia Vicente, D.; Van Gaeveren, K.; Murphy, S.L.; Vanden Abeele, M.M.P. Does Mindless Scrolling Hamper Well-Being? Combining ESM and Log-Data to Examine the Link between Mindless Scrolling, Goal Conflict, Guilt, and Daily Well-Being. J Computer-Mediated Comm 2023, 29, zmad056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, E.C. The Social Construction of Transgender Individuals and U.S. Military Policy. J Homosex 2021, 68, 2024–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.M.S.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A General Model of Cognitive Bias in Human Judgment and Systematic Review Specific to Forensic Mental Health. Law Human Behav 2022, 46, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dong, H.; Wang, X.; Feng, F.; Wang, M.; He, X. Bias and Debias in Recommender System: A Survey and Future Directions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2023, 41, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauscher, A.; Glavaš, G.; Ponzetto, S.P.; Vulić, I. A General Framework for Implicit and Explicit Debiasing of Distributional Word Vector Spaces. AAAI 2020, 34, 8131–8138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yu, C.; Fung, Y.R.; Li, M.; Ji, H. ADEPT: A DEbiasing PrompT Framework. AAAI 2023, 37, 10780–10788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Truncated Article Title | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 72 | Disability Rights and Robotics: Co-producing Futures | 2023 |

| 73 | Prosthetic Performances: Artistic Strategies | 2021 |

| 74 | Privacy in a Pandemic: An Examination | 2021 |

| 75 | Children and Online Privacy Protection: Empowerment | 2020 |

| 76 | Digital hyperconnectivity and the self | 2020 |

| 77 | Unseen potential: photovoice methods in hazard and disaster | 2019 |

| 78 | Left to their own devices? A mixed methods study | 2021 |

| 79 | The promises and challenges of clinical AI in community | 2023 |

| 80 | Assessment of digital risks in child & adolescent mental health | 2023 |

| 81 | What has been done to improve learning for intellectual | 2023 |

| 82 | Adolescents’ experiences of a theory-based behavioural | 2022 |

| 83 | Iranian nongovernmental organizations’ initiatives in COVID | 2022 |

| 84 | Considerations in pediatric intervention research: Lessons | 2022 |

| 85 | The effectiveness of web-based mobile health interventions | 2020 |

| 86 | Developing web-based health guidance for coaches | 2020 |

| 87 | Controlled trial of an mHealth intervention | 2020 |

| 88 | Acceptability and Utility of an Open-Access, Online | 2020 |

| 89 | Safety.Net: A Pilot Study on a Multi-Risk Internet Prevention | 2021 |

| 90 | Effectiveness of mobile health-based self-management | 2021 |

| 91 | Development and feasibility testing of the Comfort Ability | 2020 |

| 92 | Technological Ecological Momentary Assessment Tools | 2021 |

| 93 | “It’s like a safe haven fantasy world”: Online fandom | 2020 |

| 94 | Leveraging the Full Continuum of Care to Prevent Opioid Use | 2023 |

| 95 | Growing Up with Smartphones | 2022 |

| # | Truncated Article Title | Dependent | Advantaged | Contender | Deviant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | Disability Rights and Robotics: Co-producing Futures | ✓ | |||

| 73 | Prosthetic Performances: Artistic Strategies | ✓ | |||

| 74 | Privacy in a Pandemic: An Examination | ✓ | |||

| 75 | Children and Online Privacy Protection: Empowerment | ✓ | |||

| 76 | Digital hyperconnectivity and the self | ✓ | |||

| 77 | Unseen potential: photovoice methods in hazard and disaster | ✓ | |||

| 78 | Left to their own devices? A mixed methods study | ✓ | |||

| 79 | The promises and challenges of clinical AI in community | ✓ | |||

| 80 | Assessment of digital risks in child & adolescent mental health | ✓ | |||

| 81 | What has been done to improve learning for intellectual | ✓ | |||

| 82 | Adolescents’ experiences of a theory-based behavioural | ✓ | |||

| 83 | Iranian nongovernmental organizations’ initiatives in COVID | ✓ | |||

| 84 | Considerations in pediatric intervention research: Lessons | ✓ | |||

| 85 | The effectiveness of web-based mobile health interventions | ✓ | |||

| 86 | Developing web-based health guidance for coaches | ✓ | |||

| 87 | Controlled trial of an mHealth intervention | ✓ | |||

| 88 | Acceptability and Utility of an Open-Access, Online | ✓ | |||

| 89 | Safety.Net: A Pilot Study on a Multi-Risk Internet Prevention | ✓ | |||

| 90 | Effectiveness of mobile health-based self-management | ✓ | |||

| 91 | Development and feasibility testing of the Comfort Ability | ✓ | |||

| 92 | Technological Ecological Momentary Assessment Tools | ✓ | |||

| 93 | “It’s like a safe haven fantasy world”: Online fandom | ✓ | |||

| 94 | Leveraging the Full Continuum of Care to Prevent Opioid Use | ✓ | |||

| 95 | Growing Up with Smartphones | ✓ |

| # | Truncated Article Title | disruptor | deceiver | antisocial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | Low Self-control and Opportunity Structure on Cyberbullying | ✓ | ||

| 104 | Scrolling and the In-Between Spaces of Boredom: Marginalized Youths | ✓ | ||

| 105 | Cyberbullying Victimization and Perpetration in South Korean Youth | ✓ | ||

| 106 | Predictors for runaway behavior in adolescents in South Korea | ✓ | ||

| 107 | Associations Between Parental Maltreatment and Online Behavior | ✓ | ||

| 108 | Understanding deviance from the perspectives of youth | ✓ | ||

| 109 | Smartphone Addiction Culminating into Youth Deviance | ✓ | ||

| 110 | The digital divide in the US criminal justice system | ✓ | ||

| 111 | The Effects of Korean Parents’ Smartphone Addiction on Korean | ✓ | ||

| 112 | Exploring the Role of Self-Control Across Distinct Patterns of Cyber | ✓ | ||

| 113 | Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).