Submitted:

14 February 2024

Posted:

14 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

2.2. Measures

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Vaccine Hesitancy Rate Measurement

2.5. Validation of the Arabic Version of the COVID-19 Questionnaire

Forward and Backward Translation

2.6. Content Validity and Expert Assessment

2.7. Internal Reliability

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Ethics

3. Results

| Respondents’ Demographical Data | Data n(%) | Hesitant | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Children Age, year (Mean ± S.D.) Gender of children’s Male |

2.9 ± 0.94 168(44) |

116(44) |

|

| Female | 216 (56) | 148(56) | 0.912 |

|

Children’s Age group |

|||

|

<1 |

25 (6.5) |

20(80) |

0.227 |

|

1-4 |

101 (26.3) |

74(73) |

|

|

5-7 |

116 (30.2) |

80(69) |

|

|

8-11 |

142 (37) |

90(63) |

|

|

Relationship with child |

|||

|

Father |

207 (54) |

123(66) |

0.283 |

|

Mother |

177 (46) |

141(71) |

|

|

Age of participants, year Age group |

|||

|

18-24 |

24 (6) |

17(71) |

|

|

25-34 |

129 (34) |

94(73) |

0.744 |

|

35-44 |

192 (50) |

126(66) |

|

|

45-54 |

36 (9) |

25(69) |

|

|

≥ 55 |

3 (1) |

2(67) |

|

|

The educational level of the participants |

|||

|

Primary school |

15 (4) |

13(87) |

0.503 |

|

Secondary school |

181 (47) |

121(67) |

|

| BSc degree |

159 (41) |

110(69) |

|

| MSc degree |

25 (7) |

18(72) |

|

|

PhD |

4(1) |

2(50) |

|

| Children's Diseases | Hesitant N (%) |

Non Hesitant N(%) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus (DM) |

8(89) | 1(11) | 0.187 |

| cystic fibrosis | 5(56) | 4(44) | 0.387 |

| Sickle cell disease |

36(72) | 14(28) | 0.595 |

| Bone marrow or solid organ transplantation |

21(70) | 9(30) | 0.878 |

| Genetic/metabolic disorders |

11(64) | 6(35) | 0.713 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) |

2(100) | 0(0) | 0.339 |

| Cardiovascular diseases |

2(33) | 4(67) | 0.059 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

3(75) | 1(25) | 0.786 |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 3(43) | 4(57) | 0.136 |

| Thyroid disorder |

7(87) | 1(13) | 0.248 |

| Asthma |

14(64) | 8(36) | 0.594 |

| Thalassemia |

6(38) | 10(62) | 0.006 |

| Hemophilia |

1(25) | 3(75) | 0.058 |

| Blood cancer | 20(67) | 10(33) | 0.798 |

| Epilepsy |

26(81) | 6(19) | 0.111 |

| Depression |

2(100) | 0(0) | 0.339 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

6(75) | 2(25) | 0.700 |

| Other chronic diseases | 17(59) | 12(41) | 0.221 |

| Non chronic disease | 74(75). | 25 (25) | 0.135 |

| Questions | Strongly agree | Agree | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Unsure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Getting the vaccine is an excellent way to protect my child from COVID-19 disease | 55 (14) | 132 (34) | 28 (7) | 48 (13) | 121 (32) |

| 2- Having my child vaccinated is important for the health of others in my community | 94 (24) | 144 (38) | 14 (4) | 42 (11) | 90( 23) |

| 3- The information I receive about the COVID -19 vaccine from my child's healthcare provider is reliable and trustworthy | 74 (19) | 210 (55) | 3 (1) | 15 (4) | 82 (21) |

| 4- New vaccines like COVID -19 vaccines carry more risks than older vaccines | 35 (9) | 71 (19) | 9 (2) | 31 (8) | 238 ( 62) |

| 5- I am concerned about the severe side effects of the COVID -19 vaccine. | 86 (22) | 126 (33) | 10 (3) | 51 (13) | 111 (29) |

| 6- I think the COVID -19 vaccines might cause short-term problems for my child, like fever, pain at the injection site, and fatigue. |

64 (17) | 150 (39) | 7 (2) | 39 (10) | 124 (32) |

| 7- I think the COVID -19 vaccine might cause long-term health problems for my child | 37 (10) | 70 (18) | 14 (4) | 76 (20) | 187 (48) |

| 8- I think my child will not get sick with COVID-19 illness even if they do not get the COVID -19 vaccines | 24 (6) | 78( 20) | 33 (9) | 73( 19) | 176 (46) |

| 9- The COVID -19 illnesses could make my child very sick. | 37 (10) | 71 (19) | 14 (4) | 76 (20) | 186 (47) |

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age group of child (years) | ||

| <1 | 1.000 (reference) | |

| 1–4 | 0.116 (0.044–0.306) | 0.001 |

| 5–7 | 0.685 (0.312–1.504) | 0.346 |

| 8–11 | 0.988 (0.459–2.128) | 0.975 |

| Relationship of respondent to the child | ||

| Father | 1.000 (reference) | |

| Mother | 0.451 (0.240–0.848) | 0.013 |

| Sickle cell disease | 0.629 (0.345–1.149) | 0.132 |

| Has your child ever been infected | 1.453 (0.752–2.808) | 0.266 |

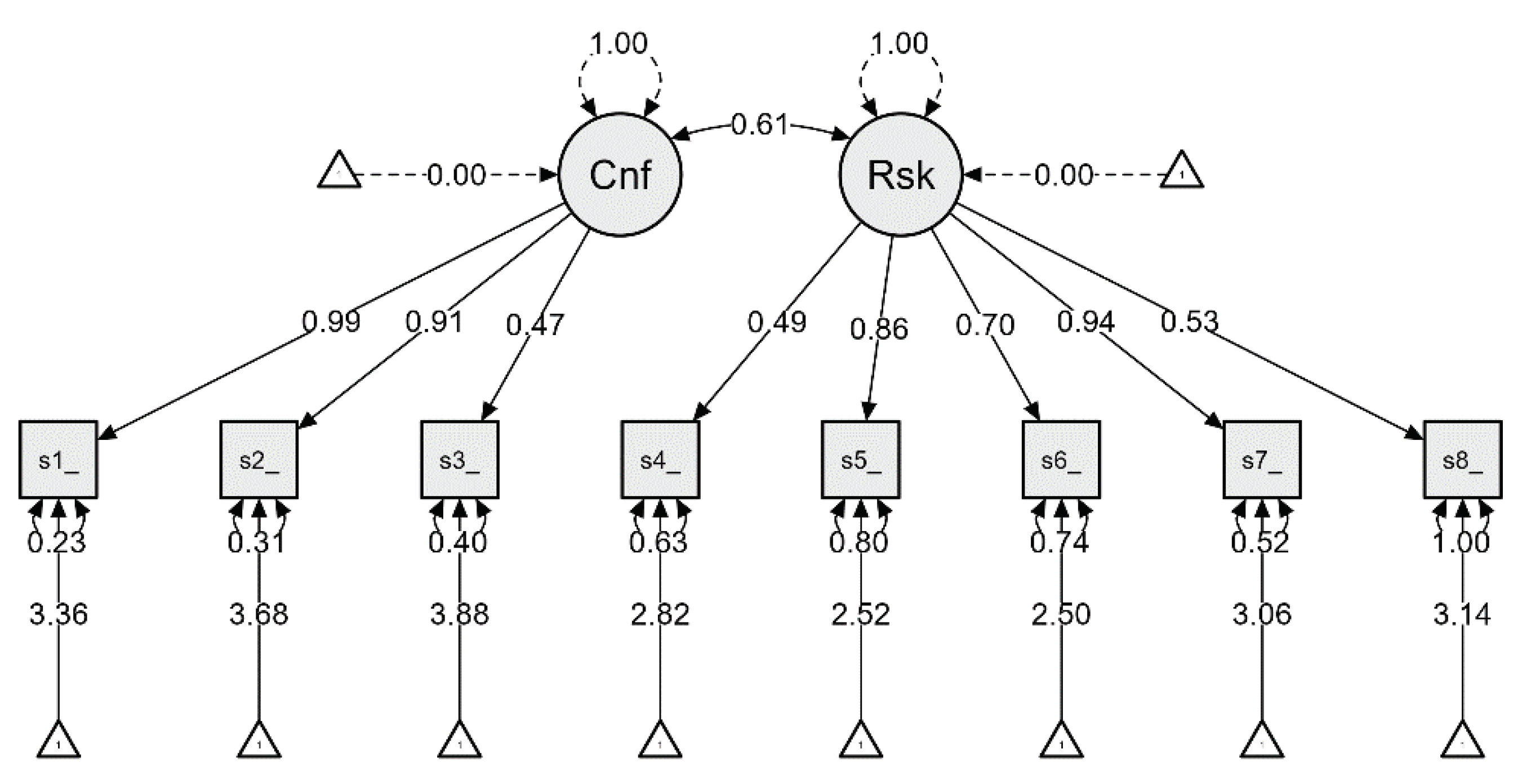

| If Item Dropped | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Cronbach's α | Item-Rest Correlation | Mean | Sd | ||

| Confidence scale1_score |

0.778 |

0.659 |

3.359 |

1.099 |

||

| scale2_score | 0.788 | 0.585 | 3.682 | 1.071 | ||

|

scale3_score Risks |

0.808 | 0.455 | 3.878 | 0.787 | ||

| scale4_score | 0.810 | 0.458 | 2.818 | 0.930 | ||

| scale5_score | 0.792 | 0.580 | 2.516 | 1.245 | ||

| scale6_score | 0.805 | 0.493 | 2.497 | 1.110 | ||

| scale7_score | 0.779 | 0.669 | 3.057 | 1.182 | ||

| scale8_score | 0.814 | 0.411 | 3.138 | 1.133 | ||

| Point estimate | 0.818 | 0.360 | 3.118 | 0.715 | ||

| 95% CI lower bound | 0.789 | 0.318 | 3.047 | 0.688 | ||

| 95% CI upper bound | 0.844 | 0.400 | 3.190 | 0.770 | ||

| 1Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Test | MSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall MSA | 0.800 | |

| scale1_score | 0.755 | |

| scale2_score | 0.726 | |

| scale3_score | 0.882 | |

| scale4_score | 0.863 | |

| scale5_score | 0.832 | |

| scale6_score | 0.805 | |

| scale7_score | 0.841 | |

|

Bartlett's test Χ² |

993 | |

| P | < | 0.001 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| scale2_score | 0.885 | 0.182 | |

| scale1_score | 0.796 | 0.253 | |

| scale3_score | 0.585 | 0.631 | |

| scale5_score | 0.711 | 0.443 | |

| scale7_score | 0.684 | 0.431 | |

| scale6_score | 0.645 | 0.572 | |

| scale4_score | 0.491 | 0.728 | |

| Factor Loadings (Structure Matrix) | |||

| scale1_score | 0.796 | ||

| scale2_score | 0.885 | ||

| scale3_score | 0.585 | ||

| scale4_score | 0.491 | ||

| scale5_score | 0.711 | ||

| scale6_score | 0.645 | ||

| scale7_score | 0.684 | ||

| Note. Applied rotation method is varimax. | |||

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Symbol | Estimate | Std. Error | z-value | P | Lower | Upper |

| Confidence | scale1_score | λ11 | 0.987 | 0.048 | 20.578 | < .001 | 0.893 | 1.081 |

| scale2_score | λ12 | 0.915 | 0.048 | 19.206 | < .001 | 0.821 | 1.008 | |

| scale3_score | λ13 | 0.471 | 0.038 | 12.288 | < .001 | 0.396 | 0.547 | |

| Risks | scale4_score | λ21 | 0.487 | 0.049 | 10.005 | < .001 | 0.391 | 0.582 |

| scale5_score | λ22 | 0.865 | 0.061 | 14.065 | < .001 | 0.744 | 0.985 | |

| scale6_score | λ23 | 0.701 | 0.056 | 12.516 | < .001 | 0.591 | 0.811 | |

| scale7_score | λ24 | 0.935 | 0.056 | 16.598 | < .001 | 0.825 | 1.046 | |

| scale8_score | λ25 | 0.531 | 0.060 | 8.828 | < .001 | 0.413 | 0.649 | |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p | Lower | Upper | |||

| Confidence | ↔ | Risks | 0.611 | 0.043 | 14.356 | < .001 | 0.527 | 0.694 |

| Chi-Square P Value 0.001 | X2/df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | TLI |

| Suggested fit model (Ref32) | 2 - 5 | ≥ 0.95 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.05 | ≥0.95 |

| 9-item parental COVID -19 VHS (full sample ) | 2.7 | 0.970 | 0.066 | 0.035 | 0.956 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andre, F.E.; Booy, R.; Bock, H.L.; Clemens, J.; Datta, S.K.; John, T.J.; et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ. 2008, 86, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappuoli, R.; Santoni, A.; Mantovani, A. Vaccines: An achievement of civilization, a human right, our health insurance for the future. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 22]. Available online: https://covid19.who.int.

- Yang, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, R.; Yange, M.; Guan, K.; Jiang, T.; et al. The deadly coronaviruses: The 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor. 1992. 2020, 109, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Guo, W.; Guo, W.; Zheng, J.; et al. systematic review and meta-analysis of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COA VID-19). J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yazidi, L.S.; Al Hinai, Z.; Al Waili, B.; Al Hashami, H.; Al Reesi, M.; Al Othmani, F.; et al. Epidemiology, characteristics and outcome of children hospitalized with COVID-19 in Oman: A multicenter cohort study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götzinger, F.; Santiago-García, B.; Noguera-Julián, A.; Lanaspa, M.; Lancella, L.; Calò Carducci, F.I.; et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child. Adolesc Health. 2020, 4, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; van Exel, J.; et al. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur. J. Health Econ. HEPAC Health Econ. Prev. Care 2020, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, R.H.; Cvejic, E.; Bonner, C.; Pickles, K.; McCaffery, K.J. Sydney Health Literacy Lab COVID-19 group. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marshoudi, S.; Al-Balushi, H.; Al-Wahaibi, A.; Al-Khalili, S.; Al-Maani, A.; Al-Farsi, N.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) toward the COVID-19 Vaccine in Oman: A Pre-Campaign Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Walker, J.L.; Paterson, P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: A multi-methods study in England. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7789–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.D.; Yan, T.D.; Seiler, M.; Parra Cotanda, C.; Brown, J.C.; Klein, E.J.; et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: Cross sectional survey. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7668–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalti, M.; Rallo, F.; Guaraldi, F.; Bartoli, L.; Po, G.; Stillo, M.; et al. Would Parents Get Their Children Vaccinated Against SARS-CoV-2? Rate and Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy According to a Survey over 5000 Families from Bologna, Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiu, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Han, Y.; Dong, S.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccine Willingness among Parents in Wuxi, China-A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Walker, J.L.; Paterson, P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: A multi-methods study in England. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7789–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temsah, M.H.; Alhuzaimi, A.N.; Aljamaan, F.; Bahkali, F.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Alrabiaah, A.; et al. Parental Attitudes and Hesitancy About COVID-19 vs. Routine Childhood Vaccinations: A National Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 752323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, O.S.; Alfayez, O.M.; Al Yami, M.S.; Asiri, Y.A.; Almohammed, O.A. Parents’ Hesitancy to Vaccinate Their 5-11-Year-Old Children Against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: Predictors From the Health Belief Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 842862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khlaiwi, T.; Meo, S.A.; Almousa, H.A.; Almebki, A.A.; Albawardy, M.K.; Alshurafa, H.H.; et al. National COVID-19 Vaccine Program and Parent’s Perception to Vaccinate Their Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakhil, H.; Albedah, N.; Alturaiki, N.; Alajlan, R.; Abusalih, H. Vaccine hesitancy towards childhood immunizations as a predictor of mothers’ intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1497–15504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; He, Y.; Shi, Y. Parents’ and Guardians’ Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.E.; Amlôt, R.; Weinman, J.; Yiend, J.; Rubin, G.J. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6059–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, A.; Hussein, S.M.; Felemban, S.G.; Mahamid, A.W. Acceptance and hesitancy of parents to vaccinate children against coronavirus disease 2019 in Saudi Arabia. PloS One 2022, 17, e0276183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.; Dergaa, I.; Abdulmalik, M.A.; Ammar, A.; Chamari, K.; Saad, H.B. BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of 4023 Young Adolescents (12-15 Years) in Qatar. Vaccines 2021, 9, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Albalas, S.; Khatatbeh, H.; Momani, W.; Melhem, O.; Al Omari, O.; et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: a multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, S.; Goldman, R.D. Determinants of parental vaccine hesitancy. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can. 2021, 67, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakhour, R.; Tamim, H.; Faytrouni, F.; Khoury, J.; Makki, M.; Charafeddine, L. Knowledge, attitude and practice of influenza vaccination among Lebanese parents: A cross-sectional survey from a developing country. PloS One 2021, 16, e0258258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsuwaidi, A.R.; Elbarazi, I.; Al-Hamad, S.; Aldhaheri, R.; Sheek-Hussein, M.; Narchi, H. Vaccine hesitancy and its determinants among Arab parents: a cross-sectional survey in the United Arab Emirates. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 3163–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, D.A.; Bou Raad, E.; Bekhit, S.A.; Sallam, M.; Ibrahim, N.M.; Soliman, S.; et al. Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) Questionnaire in Arabic Language Widely Spoken in a Region with a High Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmkamp, L.J.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Zimet, G.; Saville, A.W.; Gurfinkel, D.; Albertin, C.; et al. A validated modification of the vaccine hesitancy scale for childhood, influenza and HPV vaccines. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushariah, M.A.A.M.; Ainon, R.N.; Zainuddin, R.; Alqudah, A.A.M.; Ahmed, M.E.; Khalifa, O.O. Modern standard Arabic speech corpus for implementing and evaluating automatic continuous speech recognition systems. J. Frankl. Inst. 2012, 349, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shepherd, B.E. Discussion on ‘Assessing the goodness of fit of logistic regression models in large samples: A modification of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test’ by Giovanni Nattino, Michael L. Pennell, and Stanley Lemeshow. Biometrics 2020, 76, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.I. Development and Validation of a Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Questionnaire on COVID-19 (KAP COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagateli, L.E.; Saeki, E.Y.; Fadda, M.; Agostoni, C.; Marchisio, P.; Milani, G.P. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of Children and Adolescents Living in Brazil. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, D.E.; Andersen, J.A.; Bryant-Moore, K.; Selig, J.P.; Long, C.R.; Felix, H.C.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 2200–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Herrera-Añazco, P.; Uyen-Cateriano, A.; Toro-Huamanchumo, C.J.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; et al. Cross-sectional analysis of COVID-19 vaccine intention, perceptions and hesitancy across Latin America and the Caribbean. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 41, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, G.; Nguyen, H.T.N.; Van Tran, K.; Le An, P.; Tran, T.D. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Postgrad Med. 2022, 134, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Huang, H.; Shang, J.; Xie, Z.; Jia, R.; Lu, G.; et al. Willingness and influential factors of parents of 3-6-year-old children to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3969–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samannodi, M.; Alwafi, H.; Naser, A.Y.; Alabbasi, R.; Alsahaf, N.; Alosaimy, R.; et al. Assessment of caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4857–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, A.; Gershon, R.; Gneezy, A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: A longitudinal study. PloS One. 2021, 16, e0250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.L.; Fink, A.L.; Plebanski, M.; Klein, S.L. Sex and Gender Differences in the Outcomes of Vaccination over the Life Course. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 33, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Marriott, I.; Fish, E.N. Sex-based differences in immune function and responses to vaccination. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 109, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeens, M.A.; Hill, K.; Olsavsky, A.; Buff, K.; Stevens, J.; Akard, T.F.; et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in parents of children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.C.; Fang, Y.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, Y.Q.; et al. Parental Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination for Children Under the Age of 18 Years: Cross-Sectional Online Survey. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2020, 3, e24827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Hoq, M.; Measey, M.A.; Danchin, M. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakar, R.; Momina, A.U.; Shahzad, S.; Hayee, M.; Shahzad, R.; Zakar, M.Z. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy or Acceptance and Its Associated Factors: Findings from Post-Vaccination Cross-Sectional Survey from Punjab Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).