1. Introduction

Climate change is due to several, such as the intensive use of fossil energy resources in energy and transport, and energy waste [

1] (p. 66-75). But the large quantities of waste generated by the growing population and the mismanagement of waste of various types also have a contribution [

2]. Animals are known to provide basic protein foods for many people, along with other benefits. The increasing quantities of livestock waste, correlated with the increase in population and food needs, require proper management [

3] (p. 10219). Solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions also lie in the use of renewable energy sources, such as biogas. As a basic material, biogas can be produced from various raw materials, such as animal manure [

4] (p. 5239).

Biogas is considered a feasible solution in the context of the energy crisis [

5,

6] (p. 115870, p. 41-44) and also a solution to reduce the pollution generated by agricultural waste [

7] (p. 103577). It is worth noting that all agro-zoo-technical waste subjected to the anaerobic digestion process can become an important source of nutrients and methane production [

8,

9] (p. 101391, p. 161656). Another advantage of using the waste lies in the fact that it is widely distributed and ensures a low purchase price [

10] (p. 1-10). Following some studies, it was concluded that reactors fueled with pig manure can generate up to 6.597.520 MWh/year [

11] (p. 4933).

Biogas is usually obtained through anaerobic digestion (AD), a method that transforms waste into bioenergy [

12] (p. 126377). Anaerobic digestion is influenced by several factors, including: waste quality [

13] (p. 012113), temperature, pH, C/N ratio [

14] (p. 8721-8726), organic loading rate, and hydraulic retention time (HRT) [

15] (p. 13).

Whilst each of the factors listed earlier plays a crucial role in the anaerobic digestion process, the most important factors are the C/N ratio and the organic loading rate (OLR). The two factors have the ability to indicate the performance of the process and the stability of the digester [

16]. As such, it is extremely important to understand the properties of the raw material [

17]. One can this state that each of the listed factors is extremely important, which is why we should not pay too much attention to all of them [

18] (p. 138976).

1.1. Factors Influencing Anaerobic Digestion

1.1.1. Temperature

Temperature is one of the primary operating parameters [

19] (p. 101377), having the ability to influence the rate of microbial growth and degradation of organic matter [

20] (p. e11174). Low temperature reduces the performance of the anaerobic digestion process [

21] (p. 135808), whereas variable temperature can affect the metabolic activity of methanogens, affecting methane production [

22] (p. 128054). For example, the C/N ratio must be higher in the case of a higher temperature in order to minimize the chances of ammonia inhibition [

23]. On the other hand, a high temperature ensures a lower viscosity and an in-situ sanitation, also contributing to the reduction of pathogens [

24]. Any change in temperature greater than 1°C/day can lead to the failure of the process. Therefore, to avoid such situations, it is recommended that temperature changes be kept lower than 0.6°C/day [

25].

1.1.2. pH Value

The pH indicates the concentration of hydrogen ions present in any solution [

26] (p. 2819-2837). It can contribute to the activity of microorganisms by influencing the chemical balance of NH

3 and H

2S [

27] (p. 88-95).The optimal range in which they can develop is between 5.5 and 8.5 (almost a neutral pH). This range ensures the optimal functioning of methanogenic bacteria [

28] (p. 44-49). For a better functioning of the anaerobic digestion process, it is recommended to adopt a higher pH in the second stage than in the first [

29] (p. 1253-1271). Maintaining the pH at a certain level can be achieved by adding an alkaline substance (KOH) or by controlling the OLR [

30] (p. 102704).

Considering that the volume of biogas generated is influenced by the health of micro-organisms, it is recommended to measure the pH on a regular basis [

31] (p. 8750221).

1.1.3. C/N Ratio

The C/N ratio contributes to the efficiency of anaerobic digestion [

32] by regulating microbial growth, by improving buffer capacity, and by providing process stability [

33] (p. 1-66). The C/N ratio represents a very important factor in the production of a high level of biomethane, as this ratio indicates the degradation of organic matter by bacteria [

34] (p. 135867), [

35] (p. 621126). Pursuant to the existent literature, it is known that the C/N ratio can influence biogas production [

36].

While a high C/N ratio indicates low nitrogen content, a low C/N ratio leads to the accumulation of ammonia (produces higher alkalinity in the digester) which can lead to inhibition of the process [

23,

26,

37]. Likewise, the quality of the compost is influenced by the C/N ratio [

38] (p. 37). The recommended C/N ratio for anaerobic degradation is considered 20-30 [

27,

29], but some researchers think that lower C/N ratios (10-20) can produce good results [

39] (p. 121-181). Since a ratio lower than 20 can inhibit the process, and a ratio greater than 30 leads to a decrease in the amount of biogas [

3,

40]. Others confirm that good results can be obtained even below the value of 20, meaning significant amounts of methane [

39] (p. 121-181). The achievement of an optimal ratio is influenced by the chemical composition and biodegradability of the substrate [

41]. Some studies indicate that large amounts of biogas have been obtained in the range 15.5/1 to 19/1 and that the 16/1 ratio provides process stability but small biogas losses [

42]. In contrast, other research shows that a C/N ratio of 12.7 resulted in the highest amount of volatile organic compounds (VFAs) [

43].

1.1.4. Organic Loading Rate (ORL)

The organic loading rate indicates the amount of organic matter that must be introduced daily into the digester [

44] (p. 18374). A high loading rate of the digester with organic material can lead to the accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFA) and a low pH. Conversely, a low loading rate affects microorganisms through the lack of necessary nutrients and contributes to the production of inhibitors, such as ammonia [

45] (p. 1105-1111).

In the organic material there are volatile solids (these can be digested) and fixed solids [

46]. Volatile solids are a substance than can transform from its solid phase to its vapor phase. The fixed solids and a portion of the volatile solids are non-biodegradable [

46]. Knowing the loading rate (OLR) raises the possibility to monitor the stability of the process, the methane yield, and the structure of the microbial community [

47] (p. 103099). That is why it is important to know that OLR can positively or negatively influence the process of anaerobic digestion [

48].

1.1.5. Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT)

The hydraulic retention time (HRT) is the average time that the soluble compound remains inside the digester [

49] (p. 161-180). It is an important factor that can be used to evaluate both technical viability and economic viability [

50].

The recommended retention time is heavily reliant on the physical and chemical characteristics of the raw material. For example, animal manure has a longer retention time (20-30 days) due to the low rate of biodegradation. The same cannot be said about food waste, which has a lower retention time (less than 15 days), due to the high level of biodegradation [

51].

1.2. Identifiing the Heavy Metal Incidence in Animal Manure

The detection of the presence of heavy metals in the environment recently became a topical issue. This is due to their high bioaccumulation capacity, toxicity [

52] (p. 128341), their presence in the entire food chain, and their non-biodegradable nature [

53] (p. e0235508).

Heavy metals are part of a class of compounds that have an inhibitory effect on methanogens [

54] (p. 1880-1897).Heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Mg, Cd, Fe) end up in animal manure by adding growth-stimulating substances to animal feed [

55] (p. 2658-2668), but also in the form of contaminants. Unlike water, they have a higher density and can cause toxicity at low levels of exposure [

56] (p. 2239).

Scattered on the ground in large quantities, animal manure with a high content of heavy metals can affect the soil, water and plants [

57] (p. 4488-4498). At the same time, incompletely decomposed animal manure can burn plant roots and cause greenhouse gases [

58] (p. 75-89).

It is to be noted that the amount and number of heavy metals found in organic matter should not be ignored during the anaerobic digestion process either. The uncontrolled use of animal manure with a high content of heavy metals as raw material in the production of biogas can lead to the inhibition of the anaerobic digestion process [

59] (p. 1-14), affecting the production of biogas and methane [

60] (p. 266-272). While a high concentration of heavy metals inhibits the process of anaerobic digestion, a lower concentration can generate the growth of microorganisms [

61] (p. 100099).

Heavy metals can be toxic [

62] (p.1383-1398), stimulating or inhibiting microorganisms depending on their total concentration in the substrates or their chemical forms [

54].Unfortunately, heavy metals cannot to be destroyed upon anaerobic digestion, so they end up in the soil and plants [

63] (p. 110938).

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, a wide range of animal manure from several farms was used.

Samples were collected from various-sized private farms in Romania, including large, medium, and small ones. Small farms exhibit traditional care practices, particularly in feed supplementation with biodegradable waste. Conversely, large farms utilize automated processes with specific recipes for liquid feed production, closely monitored by specialists.

The size of the farm depends on the total number of animals raised for slaughter and/or breeding, i.e. milk and eggs. Thus, Sample A comes from a medium-sized farm consisting of about 700 pigs, Sample B was taken from a small farm with about 20 pigs, Sample C comes from a large farm with about 15,000 pigs, Sample D comes from a small pig farm with about 100 heads. Samples E and F come from cow farms. Sample E was taken from a small cow farm with about 30 head, while Sample F came from a large farm with 490 head. In the case of Sample G, the farm is of medium size, having over 6,000 chicken heads. The H Sample was taken from an ostrich farm (small size) with 100 heads. Sample I was taken from a small farm (only 10 horses).

To begin with, we have determined the C/N ratio for the following categories of animal manure: pig (Sample A), pig (Sample B), pig (Sample C), pig (Sample D), cattle (Sample E), cattle (Sample F), chicken (Sample G), ostrich (Sample H), and horse (Sample I). It is important to know the C/N ratio, since it helps us to know the speed of decomposition of organic matter that takes place in the anaerobic digestion process. Then with the help of the Niton XL3t portable analyzer we identified the heavy metals present in the organic matter for the 9 samples. To find out the amount of biogas generated by each sample, we have used a laboratory biogas production facility.

The reports C/N, as well as the rest of the experiments, were performed approximately 3 times on each sample, until results with a representative average value were obtained. In order to obtain such results, as conclusive and correct as possible, for each of the 9 characteristic samples for the 5 categories of animals, the following steps were followed:

At large farms, the samples were taken from the most populated pig shed;

The mixture with the samples thus taken, specific to the farms, was performed mechanically;

At the end, the quantity corresponding to the purpose of the analysis was retained, the quantity being subsequently subjected to various analyses (drying at 105°C, calcinations at 550°C, etc.).

Predictably, all the witness samples were kept in the freezer -1/-2 °C in labeled plastic containers, which would allow the analysis to be repeated at a later date. The purpose of preservation is to be able to repeat the experiments. Generally speaking, three determinations of the same kind were performed on the same sample (batch). For the current study, the results were averaged. For differences greater than +/-2% between the experimental results, the analysis was repeated.

Strict bio-security measures were followed during the sampling process to prevent the transmission of diseases, including African swine fever. A designated changing room-filter system was used before entering animal sheds. The first compartment stored street clothes, the second contained shower cabins, and the last was for changing sterile work equipment. Disinfection trays for shoes were used at both the entrance and exit of the changing room-filter.

2.1. Laboratory Equipment

The C/N ratio was determined using the LecoCHN 828 laboratory equipment. With the help of the equipment, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and proteins can be determined from organic matter [

64]. The equipment has an ergonomic design and offers the possibility to insert 30 samples, potentially expanding the capacity up to 120 samples. The duration of the experiment is relatively short, 2.8 minutes, which boosts productivity [

65]. Work was carried out applying standards, so the procedures used are actually those described by the standards. Drying the samples, further ongoing calcination in crucibles and weighing are effectively standard processes. The analyses were conducted three times to calculate the arithmetic mean. The afore mentioned time of 2.8 minutes represents the duration of a rapid analysis cycle for the model (FP/CN) used to increase productivity, according to the indications and instructions provided by the device manufacturer.

In order to boost productivity on FP/CN models, the fast cycle time is 2.8 minutes. Practically, 2.8 minutes represents an indication related to the operation of the device.

At the beginning of the experiment, the sample is weighed in a tin capsule and inserted into the loader. Then the sample is transported to a sealed purge chamber. This chamber is designed to remove the environment/atmospheric air.

From this chamber the purged sample is automatically transferred into a reticulated ceramic crucible from the furnace. For efficient combustion of the sample, the furnace environment consists of pure oxygen. The released carbon and hydrogen gases are measured with infrared detectors. The gas sample is passed through hot copper, which helps to remove oxygen and transform nitrogen oxides (NOx) into N2 [

66].

Two standards were used to determine the C/N ratio: DIN CEN/TS 15414-1: Solid recovered fuels- Determination of moisture content using the oven dry method- Part 1: Determination of total moisture by a reference method, and DIN EN 15407 Solid recovered fuels - Methods for the determination of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and nitrogen (N) content. The indicated standards have certainly been used by other researchers, given that they are European standards and the validation of the results requires working according to standardized procedures, so that they can be validated and compared with other results. The DIN CEN/TS 15414-1:2010 standard deals with “Solid recovered fuels. Determination of moisture content using the oven dry method, Determination of total moisture by a reference method”. It is valid for solid fuels and for biofuels. It can be purchased or consulted from the standard provider, i.e. ISO- International Organization for Standardization [

67], or from [

68].

The other standard, DIN EN 15407, addresses Solid recovered fuels- Methods for the determination of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and nitrogen (N) content. Generally speaking, by using standards, one increase productivity and quality, while minimizing errors and waste [

69]. The results are indicated by

Table 1.

Considering that heavy metals can inhibit the anaerobic digestion process, the concentration of heavy metals was determined for all the 9 samples. To detect heavy metals, each sample was heated to 550°C. The identification of heavy metals in the nine samples was carried out using the Niton XL3t portable analyzer with X-ray fluorescence (XRF) [

70]. This instrument assures a rapid and simultaneous identification of several different elements [

71] (p. 3892). It has a high sensitivity and high measuring power. Moreover, the analyzer has a hot surface adapter, which allows testing in petrochemical refineries at temperatures up to 450°C.

The analyzer can detect up to 30 elements starting from Mg to U [

72]. It is suitable for analyzing batches having a temperature in-between - 20 up to ~50°C, as it has a rechargeable battery that assures an independence of several hours (up to 8 hours) [

73] (p. 514). Such equipment is to be used also for other diverse applications: fertilizers, feed, waste, coal [

64]. The results for all animal manure analyzed are comprised in

Table 3.

3. Discussion of Findings

Table 1 shows the content of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), as well as the C/N ratio for each of the nine analyzed samples.

Table 1.

Carbon (C) content, nitrogen (N) content, and the C/N ratio.

Table 1.

Carbon (C) content, nitrogen (N) content, and the C/N ratio.

| Sample designation |

Total carbon (% by mass) |

Total nitrogen (% by mass) |

C/N |

| Sample A |

23.4 |

3.4 |

6.8 |

| Sample B |

47.1 |

3.4 |

13.8 |

| Sample C |

40.1 |

2.4 |

16.7 |

| Sample D |

45 |

4 |

11.2 |

| Sample E |

39.6 |

2.4 |

16.5 |

| Sample F |

45.3 |

1.5 |

30.2 |

| Sample G |

33 |

4.9 |

6.7 |

| Sample H |

27.6 |

1.8 |

15.3 |

| Sample I |

44 |

2 |

22 |

Although the vast majority of researchers concludes that the optimal C/N ratio must be between 20 and 30, there are researchers who demonstrated that good results can be obtained with a lower C/N ratio (10-20) [

27,

29,

39]. Following a sequence of 3 repeated analyses on the same species (for which the arithmetic mean is representative), one found; the C/N ratio for pig manure ranges between 6.8 and 16.7, for cow manure between 16.5 and 30.2, for chicken manure it is 6.7, for ostrich manure 15.3, and for horse manure 22. Similar results are also presented in the existent literature: the ratio found is 13 for pig manure, 25 for cow manure [

74], 3-10 for chicken manure, and 20-50 for horse manure [

75]. In the case of ostriches, the ratio is 8.09 [

76].

Analyzing the results obtained in this study, as well as in the other studies, one can say that the C/N ratio is important for the biogas production, but not decisive in the process.

Table 2.

The content of carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen related to the original substance.

Table 2.

The content of carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen related to the original substance.

| Sample |

Total carbon |

Total hydrogen |

Organic hydrogen |

Total nitrogen |

Unit |

| Sample A |

0.8 |

11 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

% by mass |

| Sample B |

15.1 |

9.6 |

2 |

1.1 |

% by mass |

| Sample C |

11.3 |

9.6 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

% by mass |

| Sample D |

23 |

8.7 |

3.2 |

2 |

% by mass |

| Sample E |

5.4 |

10.4 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

% by mass |

| Sample F |

6.0 |

10.4 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

% by mass |

| Sample G |

22.6 |

6.6 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

% by mass |

| Sample H |

9.3 |

8.6 |

1.2 |

0.6 |

% by mass |

| Sample I |

9.6 |

10 |

1.2 |

0.4 |

% by mass |

Table 2 indicates high values in the case of sample D. For example, the total C concentration for this sample was 23 (% by mass) compared to the original substance. A relatively close value was also recorded in the case of sample G, where the concentration of total C is 22.6 (% by mass). Regarding total hydrogen, sample A recorded the highest value (11% by mass). Identical values have been determined for samples E and F (10.4% by mass). Close to samples E and F is sample I (10% by mass).

Table 3.

The heavy metal concentration detected in the nine samples.

Table 3.

The heavy metal concentration detected in the nine samples.

| Sample |

Zinc (Zn) |

Coper (Cu) |

Iron (Fe) |

Manganese (Mn) |

Calcium (Ca) |

Potassium (K) |

|

Arsenic (As) |

|

|

|

| Sample A |

376±24 ppm |

88±11 ppm |

767±39 ppm |

227±36 ppm |

0.92±37 % |

7.51±1.01 % |

|

<2 |

|

|

|

| Sample B |

363±12 ppm |

39±7 ppm |

0.27±0.01 % |

- |

1.12±0.37 % |

4.81±0.59 % |

|

<1 |

|

|

|

| Sample C |

0.79±0.01 % |

581±20 ppm |

0.62±0.01 % |

0.12±0.01 % |

10.66±0.28 % |

3.80±0.24 % |

|

<2 |

|

|

|

| Sample D |

0.17±0.01 % |

237±12 ppm |

0.19±0.01 % |

517±37 ppm |

3.64±1.08 % |

3.54±1.19 % |

|

<1 |

|

|

|

| Sample E |

85±6 ppm |

16±7 ppm |

0.79±0.01 % |

220±30 ppm |

4.05±0.07 % |

1.64±0.06 % |

|

<2 |

|

|

|

| Sample F |

106±6 ppm |

- |

0.32±0.01 % |

186±26 ppm |

- |

- |

|

<1 |

|

|

|

| Sample G |

878±21 ppm |

233±15 ppm |

0.17±0.01 % |

0.12±0.01 % |

14.47±0.36 % |

8.96±0.36 % |

|

<2 |

|

|

|

| Sample H |

633±17 ppm |

82±11 ppm |

1.03±0.01 % |

522±46 ppm |

8.94±0.80 % |

2.48±0.64 % |

|

<4 |

|

|

|

| Sample I |

249±10 ppm |

50±8 ppm |

2.22±0.01 % |

- |

7.67±0.10 % |

6.79±0.11 % |

|

<2 |

|

|

|

Animal manure is often used as organic fertilizers (amendments) to improve soil quality [

77]. The quality of manure depends on several factors such as the type of animal, age of animal, and feed administered [

78]. Unfortunately, however, they often contain components that affect plants, animals and human health [

79] (p. 850).

Table 3 indicates the heavy metal concentration detected in the 9 analyzed samples. The table shows that Sample A (pig manure), Sample G (chicken manure) and Sample H (ostrich manure) contain the highest accumulation of heavy metals. Pig manure (Sample A) contains significant amounts of Fe (767±39 ppm), Zn (376±14 ppm), Mn (227±36 ppm). In smaller quantities we find metals such as Cu and Ca. In the case of Sample G (chicken manure), the Zn concentration prevails (878±21 ppm), followed by Cu (233±15 ppm). Fe, Ca and Mn can be found in lower concentrations. Large amounts of Zn are also found in Sample H (ostrich manure). The concentration of Zn in the ostrich sample is 633±17 ppm, followed by Mn (522±46 ppm). Metals such as Fe, Cu and Ca are found in lower concentrations. The other analyzed samples also contain amounts of metals, but their concentration is lower compared to the previously presented samples.

The results of the research indicate that the highest amount of Fe 16,363.3 (mg∙kg-1) was found in pig manure, whilst the lowest in chicken manure 852.3 (mg∙kg-1). In addition to Fe, concentrations of Mn have also been detected, e. g. 370.0 (mg∙kg-1) in cattle, and Zn 94.3 (mg∙kg-1) in horse manure [

15]. In another study, amounts of Cu (642.1 mg Cu/kg dm) and As (8.6 mg As/kg dm) were identified in animal Researches such as (M. Vukobratovic et al.) and (F. Zhang et al.) have shown in their studies that heavy metals such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), arsenic (As), manganese (Mn) [

55,

80] are found in different concentrations in animal manure. Thus, in his study M. Vukobratovic et al. [

80] determined the concentration of heavy metals in compost obtained from several types of manure. Cu (65.6 mg Cu/kg dm and 31.1 mg Cu/kg dm) was detected in chicken and cow manure, respectively [

55]. These results are also confirmed in this study. Furthermore, the information detailed on in the article "Composting Manure" is corroborates this study and in those previously presented. In this article it is stated that the manure quality is influenced by several factors including the type of animal, the age of the animal, and the feed administered [

78]. For example, the presence of Cd (Cadmium) in the soil can affect soil microbes and their activity, such as mineralization, which then changes the ecological balance [

81] (p.1008).

Regarding biogas production, the experiment was conducted using the Automatic Methane Potential Test System (AMPTS II) bioprocess. It consists of several digesters allowing samples to be carried out in parallel. To maintain a constant temperature (37°C), digesters are kept in an 18-liter thermostatic water bath. The equipment is also equipped with a device for measuring the volume of gases (in this case CH3). The data ensued automatically, being processed by the sensors and the program serving the bio-processor used in the experiment [

82].

The experiment ran over 30 days, but starting from day 21 onward, no changes in measured values (specifically, the amount of methane produced) were observed. Consequently, only significant results were retained in the graphs.

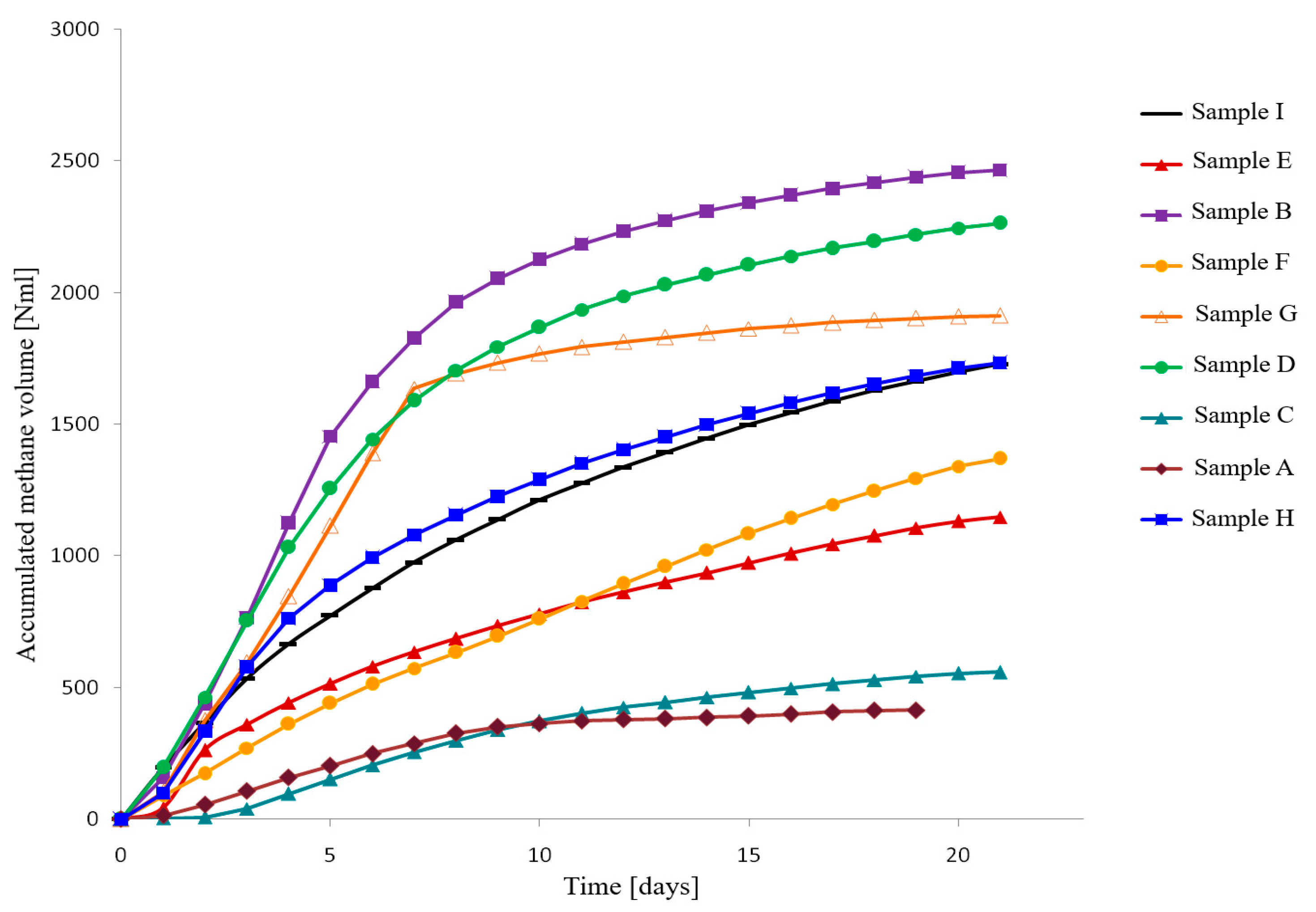

Figure 1 shows the volume of methane accumulated by each of the 9 analyzed substrates. Among all analyzed substrates, Samples B (2464.5 Nml), D (2262 Nml) and G (1911.8 Nml) recorded the highest values. At the opposite pole are Sample A (414.1 Nml) and Sample C (558.3 Nml).

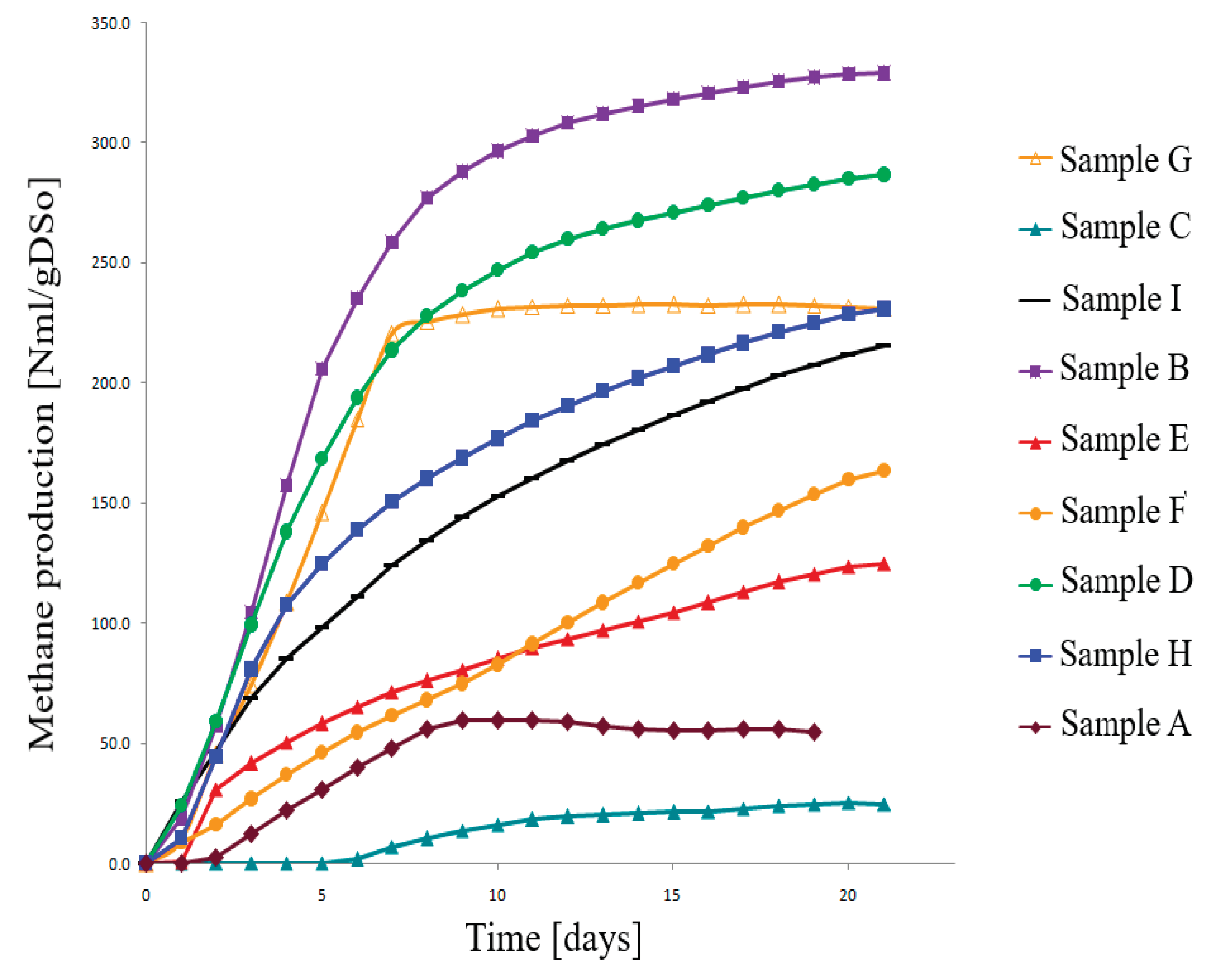

The curves shown in

Figure 2 indicate that Sample B recorded the highest biogas production. The value achieved by this substrate is 328.8 Nml/g DSo (DSo- dry matter basis). Among all the substrates analyzed, the lowest methane production was recorded in Sample C during the sixth day (1.7 Nml/gDSo). Although the values of this sample (Sample C) recorded daily increments, the recorded values were still small compared to the other substrates.

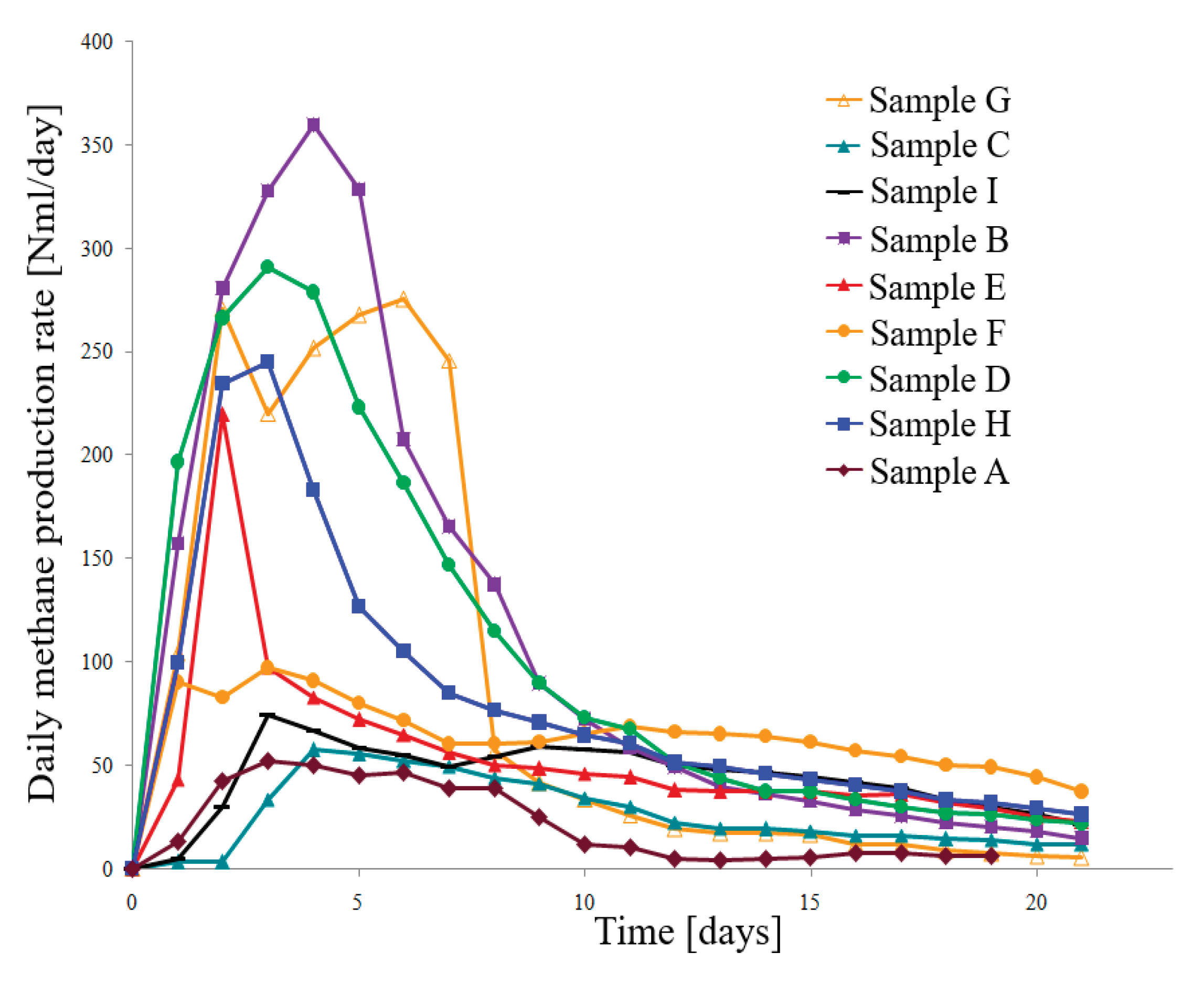

As shown in

Figure 3, the daily rate of methane production varied from one day to another. The highest values were recorded in the first 8 days of the experiment, followed by several days in which biogas production was relatively constant. Towards the end of the experiment, the daily rate of methane production began to decrease. As in the case of the 2 graphs presented previously (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), Samples B, D and G generated the highest amount of methane/day. Samples A and C generated small amounts of biogas during the entire experiment.

To obtain the quantities of biogas shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the experimental input data, presented in the table number 4, were used.

Table 4.

Biogas experiment input boards.

Table 4.

Biogas experiment input boards.

| Sample |

Input material [g] |

Inoculum [ml] |

| Sample A |

190 |

210 |

| Sample B |

24 |

376 |

| Sample C |

35 |

365 |

| Sample D |

13 |

387 |

| Sample E |

39 |

361 |

| Sample F |

42 |

358 |

| Sample G |

12 |

388 |

| Sample H |

49 |

351 |

| Sample I |

30 |

370 |

According to the instructions for use of the bio-digester, all experiments were conducted at a temperature of 37°C. The operating time the agitator was set to 300 seconds, while the rest time of the agitator was set to 3,600 seconds [

82].

5. Conclusions

This study investigated how C/N ratio and heavy metal concentrations in animal manure are impacting the biogas production process of these raw materials. The main results indicate the following:

Related to the analyzed lots, the C/N ratio records values ranging from 6.7 (Sample G, medium-sized chicken farm) and 6.8 (Sample A, medium-sized pig farm), up to 30.2 (Sample F, medium-sized cow farm).The greatest methane production is the one achieved by Sample B (small family pig farm), despite the C/N ratio equaling 13.8. The high production of methane in the case of this sample can also derive from animal feeding, which, in Romania, consists not only of specific feed, but also of biodegradable food residues from the household. Another category of manure standing out as beneficial to biogas production is pig manure coming from a small farm (Sample D), in which case the average ratio determined is 11.2. As a matter of fact, these conclusions reflect the importance of the C/N ratio for biogas production, with the range in which it varies potentially being extended to even below 20. This conclusion is also highlighted by other authors. According to the obtained results, it is concluded that even for values up to 10 for the C/N ratio, the biogas production is possible. It can thus be stated that detecting the C/N ratio is important, but not necessarily decisive in the amount of biogas generated. An explanation can be related to the feed recipes, stating that in the case of Sample B (small pig farm) the feed is also administered based on biodegradable household waste.

Related to the content of heavy metals in the manure batches, there is a dispersion of the determined values, yet the values are still grouped as an order of magnitude, comparable to other bibliographic sources. In the case of Potassium (K), the range covered by the determined values is narrower, varying, according to

Table 3, between 1.64 (Sample E) and 8.96 (Sample G). For Sample D, it is found that the values of heavy metals are included in the variation range recorded for the other samples, without approaching the extreme values recorded. An explanation is related to the feed recipes as well. It turns out that the presence of heavy metals is important to know. The results have been compared with similar ones from other groups of authors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-A.H.; methodology, I.-A.H.; validation, I. I.; formal analysis, I.I.; investigation, I.-A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, I.-A.H., I.I.; writing—review and editing, I.-A.H., M.-C.M, I.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Not applicable as the study does not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Data contained within the article are presented as variable values and graphical representations.

Acknowledgments

The thanks of the authors go to the two distinguished professors: Univ.Prof. Dr. Negrea Petru from the Research Institute for Renewable Energies of the Politehnica University of Timisoara, and Univ. Assoc Prof. Dr. Vintila Teodor from the "King Michael I "University of Life Sciences from Timisoara”, Department of Biotechnology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Offie, I.; Piadeh, F.; Behzadian, K.; Campos, L.C.; Yaman, R. Development of an artificial intelligence-based frame work for biogas generation from a micro anaerobic digestion plant. Waste Manage. 2023,158, p. 66-75. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; He, T. Zhang, Y. Treatment and utilization of swine wastewater- A review on technologies in full-scale application. Science of The Total Environment. Publisher: Elsevier, 2023, 880. [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Ceci, P.; Cafaro, C.; Corazzi, G.; Avino, P. Production of biogas and biomethane as renewable energy sources: A review. Appli. Sci.2023, 13, p.10219. [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.; Chomac-Pierzecka, E.; Kokiel, A.; Rozycka, M.; Stasiak, J.; Sobon, D. Economic conditions of using biodegradable waste for biogas production, Using the example of Poland and Germany. Energies 2022, 15, p. 5239. [CrossRef]

- Mohite, J.A.; Manvi, S.S.; Pardhi, K.; Khatri, K.; Bahulikar, R.A.; Rahalkar, M.C. Thermotolerant methanotrophs belonging to the Methylocaldum genus dominate the methanotroph communities in biogas slurry and cattle dung: A culture-based study from India. Environ. Res. 2023, 228, p. 115870. [CrossRef]

- Sumardiono, S.; Matin, H.H.A.; Sulistianingtias, I.; Nugroho, T.Y.; Budiyono, B. Effect of physical and biological pretreatment on sugarcane bagasse waste-based biogas production Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 87, pp. 41-44. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Ferrari, G.; Pezzuolo, A.; Alengebawy, A.; Jin, K.; Yang, G.; Li, Q.; Ai, P. Evaluation and analysis of biogas potential from agricultural waste in Hubei Providence, China. Agric. Syst. 2023, 205, p. 103577. [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, S.; Endo, R.; Shibuya, T. Acidophilic nitrification of biogas digestates accelerates sustainable hydroponics by enhancing phosphorus dissolution. Bioresources Techology Reports 2023, 22, p. 101391. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Aryal, N.; Li, Y.; Horn, S.J.; Ward, A. J. Developing a biogas centralized circular bioeconomy using agricultural residues- Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, p. 161656. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Su, L.; Sun, X.; Liu, C.; Ji, R.; Zhen, G.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L. Thermophilic solid-state anaerobic digestion of corn straw, cattle manure, and vegetables waste: Effect of temperature, total solid content, and C/N ratio. Archaea 2020, 2020, p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.M.; Lim, T.-T. Use of regression models for development of a simple and effective biogas decision-support tool. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, p. 4933. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, J.; Yue, Y.; Mu, W.; Xu, G.; Ying, J. Energy evolution of biogas production system in China from perspective of collection radius. Energy 2023, 265, p. 126377. [CrossRef]

- Arip, A.G.; Widhorini Sustainable ways of biogas production using low-cost materials in environment. J Phys Conf Ser 2021, 1933, p .012113, https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1933/1/012113.

- Fagbeni, L.; Adamon, D.; Ekouedjen, E.K. Modeling Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio Influence on Biogas Production by the 4 th-order Runge-Kutta Method. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, p. 8721-8726. [CrossRef]

- Tshemese, Z.; Deenadayalu, N.;Linganiso, L.Z.; Chetty, M. An Overview of Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion and the Possibility of Using Sugarcane Wastewater and Municipal Solid Waste in a South African Context. Appl. Syst Innov. 2023, 6, p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Ammar, M.; Korai, R.M.; Ahmad, N.; Ali, A.; Khalid, M.S.; Zou D.; Li, X. Impact of C/N ratios and organic loading rates of paper, cardboard and tissue wastes in batch and CSTR anaerobic digestion with food waste on their biogas production and digester stability. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2, p. 1436. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Montero, X.; Mercado-Reyes, I.; Valdez- Solórzano, D.; Santos- Ordoñez, E.; Delgado-Plaza, E. 2022 Effect of temperature and the Carbon-Nitrogen (C/N) ratio on methane production through anaerobic co-digestion of cattle manure and Jatropha seed cake 20th International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’ 22). [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, O.; Ozkaya, B. Prediction of biogas production of industrial scale anaerobic digestion plant by machine learning algorithms. Chemosphere 2023, 335, p. 138976. [CrossRef]

- Mortezaei, Y.; Williams, M.R.; Demirer, G.N. Effect of temperature and solids time on the removal of antibiotic resistance genes during anaerobic digestion of sludge. Bioresource Technology Reports 2023, 21, p. 101377. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez- Jimenez, L.M.; Perez-Vidal, A.; Torres-Lozada, P. Research trends and strategies for the improvement of anaerobic digestion of food waste in psychrophilic temperatures conditions. Heliyon 2022, 8, p. e11174. [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, T.; Nakamura, M.; Oritate, F.; Nishimura F. Comparative anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge at different temperatures with and without heat pre-treatment. Chemosphere 2022, 307, p.135808. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Xia, A.; Feng, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Effects of oxytetracycline on mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion for biogas production from swine manure. Fuel 2023, 344, p. 128054. [CrossRef]

- Bhajani, S.S.; Pal, S.L. Review: Factors affecting biogas production. IJRASET 2022, 10, . [CrossRef]

- Ahlberg-Eliasson, K.; Westerholm, M.; Isaksoon, S.; Schnurer, A. Anerobic digestion of animal manure and influence of organic loading rate and temperature on process performance, microbiology, and methane emission from digestates. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2021.740314.

- Slim, Y.E.; Bahnasawy, A.H.; Khater, E.G.; Hamouda R.M. Review: Biogas productivity and quality as influenced by fermentation temperature and agitation process. ICBAA, Benha University, 8 April 2021, https://assjm.journals.ekb.eg/article_195611_6ec4ea3a0caee058f55cd05f2af4130c.pdf.

- Uddin, M.M.; Wright, M.M. Anaerobic digestion fundamentals, challenges, and technological advances. Physical Sciences Reviews 2023, 8, p. 2819- 2837. [CrossRef]

- Ceron-Vivas, A.; Caceres-Caceres, K.T. Influence of pH and the C/N ratio on the biogas production of wastewater. Revista Facultand de Ingineria Universidad de Antioquia 2019, 92, p. 88-95. [CrossRef]

- Sari, L.N.; Prayitno, H.; Farhan, M.; Syaichurrozi, I. Review: Biogas production from rice straw. WCEJ 2022, 6, p. 44-49, https://www.academia.edu/96394440/Review_Biogas_Production_from_Rice_Straw.

- Laiq Ur Rehman, M.; Iqbal, A.; Chang, C.; Li, W.; Ju, M. Anaerobic digestion. Water Environ. Res. 2019, 91, p. 1253-1271. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; Tsai, C.Y.; Liu, C.W.; Wang, S.W.; Kim, H.; Fan, C. Anaerobic co-digestion of agricultural wastes toward circular bioeconomy. iSciene 2021, 24, p. 102704. [CrossRef]

- Messineo, A.; Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Biogas production and applications in the sustainable energy transition. J. Energy 2022, 2022, p. 8750221. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Prasad, N.; Selvaraju, S. Reactor design for biogas production- A short review. JEPT 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, R.U.; Ahmed, M.; Lim, T.T.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z, Li, Y.; Zhou, Y. Chapter One- Arrested methanogenesis: Principles, practices, and perspectives. Elsevier; Volume 7, p. 1-66. [CrossRef]

- Bumharter, C.; Bolonio, D.; Amez, I.; Garcia Marinez, M.J.; Ortega, M. F. New opportunities for the European biogas industry: A review on current installation development, production potentials and yield improvements for manure and agricultural waste mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, p. 135867, . [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, T.; Wei, Z.; Banerjee, S.; Friman, V.-P.; Mei, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q. Livestock manure type affects microbial community composition and assembly during composting. Front Microbial 2021, 12, p. 621126, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.621126.

- Melis, E.; Asquers, C.; Carboni, G.; Scano, E.A.; Garcia-Tejero, I.V.; Duran-Zuazo, V.H. Chapter 4- Role of cannabis sativa L. in energy production: residues as a potential lignocellulosic biomass in anaerobic digestion plants. Current Applications, Approaches, and Potential Perspectives for Hemp, ed.; Editor: Garcia-Tejero, I.F., Duran-Zuazo V.H., Eds.; Publisher: Academic Press, 2023, p. 111-199. [CrossRef]

- Ngan, N.V.C.; Chan, F.M.S.; Nam, T.S.; Van Thao, H.; Maguyon- Detras, M.C.; Hung, D.V.; Cuong, D.M.; Van Hung, N.; Gummert, M.; Hung, N.V.; Chivenge, P.; Douthwaite, B. Anaerobic digestion of rice straw for biogas production. Sustainable rice straw management. Publisher: Springer International Publishing, 2020, p. 65-92. [CrossRef]

- El-Mrini, S.; Aboutayeb, R,;Zouhri, A Effect of initial C/N ratio and turning frequency on quality of final compost of turkey manure and olive pomace. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2022, 69, p. 37. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. Xu, F.; Ge, X.; Li Y. Chapter Four- Biological treatment of organic materials for energy and nutrients production- Anaerobic digestion and composting. Advances in Bioenergy. Publisher: Elsevier, 2019, 4, p. 121-181. [CrossRef]

- Muthudineshkumar, R.; Anand, R. 6- Anaerobic digestion of various feedstocks for second-generation biofuel production. Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy. Publisher: Woodhead Publishing, 2019, p. 157-185. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Khim, J.D. Application of a full-scale horizontal anaerobic digester for the co-digestion of pig manure, food waste, excretion, and thickened sewage sludge. Processes 2023, 11, p. 1294. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.S.; David E.B. Carbon/Nitrogen ratio and anaerobic digestion of swine waste. Transactions of the ASAE 1978, 21, p. 0537-0541. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lian, T.; Dong, H. Production of short-chain carboxylic acids by co-digestion of swine manure and corn silage: Effect of carbon-nitrogen ratio. Transactions of the ASABE 2020, 63, p. 445-454. [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, J.A.; Greses, S.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, C. Impact of organic loading rate in volatile fatty acids production and population dynamics using microalgae biomass as substrate. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, p. 18374. [CrossRef]

- Tassakka, M.I.S.; Islami, B.B.; Saragih, F.N.A.; Priadi, C.R. Optimum organic loading rates (ORL) for food waste anaerobic digestion: Study case Universitas Indonesia. IJT 2019, 10, p. 1105-1111. [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.; Shayegan, J. Effect of organic loading rates (ORL) on production of methane from anaerobic digestion of vegetables waste. World Renewable Energy Congress, Linkoping, Sweden, 8-13 May 2011, http://dx.doi.org/10.3384/ecp11057411.

- Ahmad, A.; Grufran, R.; Nasir, Q.; Shahitha, F.; Al-Sibani, M.; Al-Rahbi, A.S. Enhanced anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and solid poultry slaughterhouse waste using fixed bed digester: Performance and energy recovery. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, p. 103099. [CrossRef]

- Shafizadeh, A.; Danesh, P. Chapter 15- Biomass and Energy Production: Thermochemical methods. Biomass, biorefineries and bioeconomy. Editor: Mohamed Samer, Bioenergy, Publisher: IntechOpen 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Qiao, W.; Guo, J.; Sun, H.; Stefanakis, A.; Nikolaou, I. Chapter 10- Manure treatment and recycling technologies. Circular Economy and Sustainability. Publisher: Elsevier 2022, Volume 2, p. 161-180. [CrossRef]

- Nelabhotla, A.B.T.; Khoshbakhtian, M.; Chopra, N.; Dinamarca, C. Effect of hydraulic retention time on MES operation for biomethane production. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- El Mashad, H.; Zhang R. Biogas energy from organic wastes. Introduction to Biosystems Engineering. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Abomohra, A.E.F.; El- Hefnawy, M.E.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Li, L.; Tang, J; Mohammed, S. Sequential bioethanol and biogas production coupled with heavy metal removal using dry seaweeds: Towards enhanced economic feasibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, p. 128341. [CrossRef]

- Montusiewicz, A. Szaja, A. Musielewicz, I. Cydzik- Kwiatkowska, A.; Lebiocka, M. Effect of bioaugmentation on digestate metal concentrations in anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, p. e0235508. [CrossRef]

- Czatzkowska, M.; Harnisz, M.; Korzeniewska, I.; Inhibitors of the methane fermentation process with particular emphasis on the microbiological aspect: A review. Energy Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, p. 1880-1897. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, W. Content of heavy metals in animal feeds and manures from farms of different scales in Northeast China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 9, p. 2658-2668. [CrossRef]

- Hejna, M.; Onelli, E.; Moscatelli, A.; Bellotto, M.; Cristiani, C.; Stroppa, N.; Rosii, L.; Heavy-Metal phytoremediation from livestock wastewater and exploitation of exhausted biomass. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, p. 2239. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tong, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Biogas production and metal passivation analysis during anaerobic digestion of pig manure: Effects of a magnetic Fe3O4/FA composite supplement. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, pp. 4488-4498. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zou, D.; Wu, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, F.; Xiao, Z.; Review on fate and bioavailability of heavy metals during anaerobic digestion and composting of animal manure. Waste Manag. 2022, 150, p. 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Golub, N.; Shynkarchuk, A.; Kozlovets, O.; Kozlovets, M. Effects of heavy metal ions (Fe3+, Cu2+, Zn2+ and Cr3+) on the Productivity of Biogas and Biomethane Production. ABB 2022, 13, p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Majeed, S.; Xu. R.; Zhang, K.; Kakade, A.; Khan, A. Hafeez, F.Y.; Mao, C.; Liu, P.; Li, X. Heavy metals interact with the microbial community and affect biogas production in anaerobic digestion: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 240, p. 266-272. [CrossRef]

- Al bkoor Alrawashdeh, K. Anaerobic co-digestion efficiency under the stress exerted by different heavy metals concentration: An energy nexus analysis. Water-Energy Nexus 2022, 7, p. 100099. [CrossRef]

- Mudhoo, A.; Kumar, S. Effects of heavy metals as stress factors on anaerobic digestion processes and biogas production from biomass. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, p. 1383-1398. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; Carswell, A.; Misselbrook, T.; Shen, J.; Han, J. Fate and transfer of heavy metals following repeated biogas slurry application in a rice-wheat crop rotation. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 270, p. 110938. [CrossRef]

- ***https://www.leco.com/product/828-series, accessed: 28 05 2023.

- ***https://www.labcompare.com/Laboratory-Analytical-Instruments/176-Total-Nitrogen-Analyzer-TN-Analyzer/?search=nitrogen+analyzer+total+, accessed: 28 05 2023.

- Carbon/Nitrogen Analyzer with Cornerstone. Instruction Manual CN 828/FP 828 P/FP 828, version 2.9.X, part. Number 200-793, February 2020, https://ro.scribd.com/document/459696225/828-series-Instruction-Manual-V2-9-x-February-2020-200-793-pdf.

- ***https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/iso/, accessed: 28.11.2023.

- ***https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/930377f4-91d8-4a42-8067-2bffe88626e0/cen-ts-15414-1-2010, accessed: 28.11.2023.

- ***https://www.en-standard.eu/din/, accessed: 28.11.2023.

- ***https://www.pine-environmental.com/products/niton_xl3t_xrf_soil_analyser, accessed: 28.05.2023.

- Horf, M.; Gebber, R.; Vogel, S.; Ostermann, M.; Piepel, M.-F.; Olfs, H.-W. Determination of nutrients in liquid manures and biogas digestates by portable energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Sensors 2021, 21, p. 3892. [CrossRef]

- ***https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/10131166, accessed: 28 05 2023.

- Pang, B.; Wu, S.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, L.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Shi, G. Rapid exploration using pXRF combined with geological connotation method (GCM): A case study of the nuocang cu polymetallic district, Tibet. Minerals 2022, 12, p. 514. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Optimizing the amount of pig manure in the vermicomposting of spent mushroom (Lentinula) substrate. Peer J 2020, 8, p. e10584. [CrossRef]

- Mutungwazi, A.; Ijoma, G.N.; Ogola, H.J.O.; Matambo, T.S. Physico-chemical and metagenomic profile analyses of animal manures routinely used as inocula in anaerobic digestion for biogas production. Microorganisms 2022, 10, p. 671. [CrossRef]

- Al-mamouri, A.K.; Jassim, H. Improving of biogas production using different pretreatment of rice husk inoculated with ostrich dung. TJER 2021, 18, p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Goldan, E.; Nedeff. V.; Barsan, N.; Culea, M.; Panainte-Lehadus, M.; Mosnegutu, E.; Tomezei, C.; Chitimus, D.; Irimia, O. Assessment of manure compost used as soil amendment-A review. Processes 2023, 11, p. 1167. [CrossRef]

- ***https://www.carryoncomposting.com/443725801.html, accessed: 27.11.2023.

- Akhter, P.; Khan, Z.I.; Hussain, M.I.; Ahmad, K.; Farooq Awan, M.U.; Ashfaq, A.; Chaudhry, U.K.; Fahad Ullan, M.; Abideen, Z.; Almaary, K.S.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Elshikh, M.S. Assessment of heavy metal accumulation in soil and garlic influenced by waste-derived organic amendments. Biology 2022, 11, p. 850. [CrossRef]

- Vukobratovic, M.; Vukobratovic, Z.; Loncaric, Z.; Kerovac, D. Heavy metals in animal manure and effects of composting on it. Acta Horticulture 2014, 1034, p. 591-597. [CrossRef]

- Shah, G.M.; Farooq, U.; Shabbir, Z.; Guo,J.; Dong, R.; Bakhat, H.F.; Wakeel, M.; Siddique, A.; Shahid, N. Impact of Cadmium contamination on fertilizer value and associated health risks in different soil types following anaerobic digestate application. Toxics 2023, 11, p. 1008. [CrossRef]

- ***https://bpcinstruments.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022_Gas-Endeavour-Manual.pdf, accessed: 24.11.2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).