Introduction

COVID-19 vaccines were developed and approved for emergency use in less than a year after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic [

1]. As of February 17

th, 2024, over 5 billion people (67% of the world population) has been vaccinated with a complete primary series of a COVID-19 vaccine [

2]. Through January 26

th, 2024, there have been 1,626,370 adverse event reports, including 214,248 hospitalizations, 37,100 deaths, 21,431 heart attacks, and 9,116 thrombocytopenia cases associated with COVID-19 vaccines in the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) [

3].

Some batches of the BNT162b2 (Pfizer) vaccine have been shown to exhibit abnormally high numbers of suspected adverse events (SAEs). It has been estimated that 71% of SAEs occurred in only 4.2% of BNT162b2 batches [

4]. Pulmonary hemorrhage has been reported as a serious adverse event following COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) [5-7]. Here, we report an autopsy case of a 47-year-old male that died unexpectedly from pulmonary hemorrhage over one year after primary COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2 and perform an investigation into the BNT162b2 batch he received. Moreover, we propose autopsy recommendations for individuals that have received one or more COVID-19 vaccines to better ascertain the cause of death.

Case Presentation

A 47-year-old male, weighing 173 pounds, was healthy in adult life, had no chronic illnesses and took no medications. He had a normal physical exam and routine laboratories on September 15th , 2020. This was the last time he was examined by a doctor. He had no suspected or documented episodes of COVID-19 illness. On July 1st, 2021, he completed a COVID-19 vaccination primary series with two doses of BNT162b2. With each COVID-19 vaccine administration, he had an injection site reaction, malaise, weakness, and felt sufficiently ill that he could not work the next day. After recovery from the primary series, his only health encounter was a dental appointment where his blood pressure was found to be 134/87. Ten days before his death, on December 28th, 2022, there was a fire drill at work and the elevators where stopped, so he had to go up 10 flights of stairs after which he remarked to a colleague that he was out of breath. About three days before the date of death, both the patient and his wife were infected with a mild viral upper respiratory tract infection, and this was nearly resolved on the day of death. He awoke on the day of death with hoarseness. Throughout the day, his symptoms worsened. Around 12:30, the hoarseness became severe, and he could barely talk. The patient appeared to have fallen asleep around 14:50 on the floor and made some unusual snoring and gurgling sounds. His family noticed he was unresponsive and turning blue, so they called 911 for emergency medical assistance. The paramedic records indicate the estimated time of cardiac arrest was 15:00, the dispatch call was at 15:11, and the unit was on scene at 15:22. The paramedics indicated “patient was bleeding profusely out of his mouth.” He received chest compressions and bag/valve ventilation throughout the resuscitation. The paramedics noted multiple times that profuse bleeding clogged up tubes, required suctioning and worked to prevent prompt airway access. The initial cardiac rhythm was ventricular fibrillation for which there were six defibrillation attempts at 360 J. He underwent successful endotracheal intubation on the second attempt at 15:45 and had intravenous lines placed. He received three doses of epinephrine 1:10, amiodarone 300 mg, 150 mg, normal saline 1000 ml, and tranexamic acid 1000 mg was given in an attempt to stop the hemorrhage. The patient remained unresponsive to these measures and was transported to the hospital where he was declared dead at 16:08 on January 7th, 2023, which was 555 days after the last COVID-19 vaccination.

Postmortem Findings

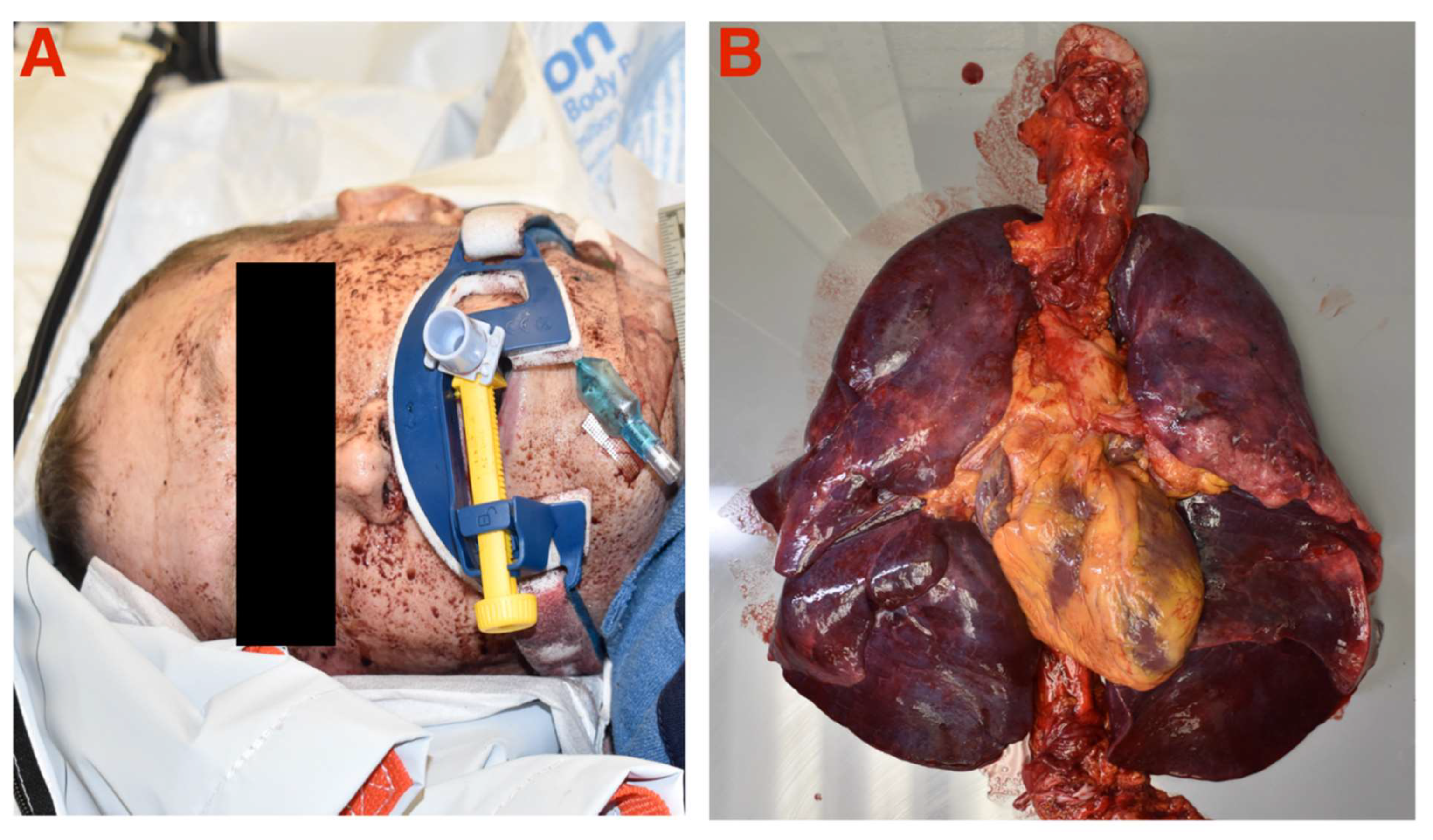

Gross examination revealed evidence of oral expectoration of blood during cardiac arrest and massively congested lungs with blood

(Figure 1). An autopsy was performed by the County Medical Examiner with the major findings of: 1) dark red, purple lungs with marked amounts of blood and frothy fluid, right lung weight 1552 g, left lung weight 1333 g (normal ~250 g [

8]), no pulmonary embolism, 2) heart weight was normal 474 grams (normal < 500 g [

9]) and myocardial tissue was normal, 3) coronary arteries estimated visually without detailed sectioning: left main normal, left anterior descending 90%, left circumflex 90%, right coronary 60%, stenoses without thrombus or occlusion, 4) moderate atherosclerosis in the aorta and basilar arteries to the neck, 5) there were multiple small faint contusions on the arms and legs. Pertinent negatives: no gastrointestinal or cerebral hemorrhage, no myocardial infarction, toxicology was negative, tests for COVID-19 and upper respiratory pathogens were negative. The medical examiner concluded that the patient died from atherosclerotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease. However, the patient had no recorded history of hypertension and the pulmonary hemorrhage was not cited as the major cause of death or as a contributing factor by the medical examiner in the report or on the death certificate. There were no tissue stains for COVID-19 vaccine mRNA or its encoded Spike protein.

COVID-19 Vaccine Batch Analysis

To conduct a thorough analysis of the specific COVID-19 vaccine batch administered to this individual, we employed a digital resource known as "

How Bad is My Batch?" [

10]. This tool aggregates data from VAERS [

3], methodically organizing it to present all adverse events associated with specific vaccine batches. This approach allows for a detailed and systematic examination of the batch in question, providing a comprehensive view of any potential adverse effects reported. The patient received two doses of a BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, which both belonged to the batch EW0175. A review of batch information indicates there were 29 reports of death from his batch through February 2, 2024, however, this case had not yet been reported to VAERS. Batch EW0175 is among the top 2.8% for number of reported deaths out of all Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine batches listed in VAERS (ranked 131 out of 4,730). Analysis of batch EW0175 indicated the lethality of injection (number of deaths among total EW0175 adverse event reports) was 1.69%. Since he received two doses, his risk of death may have been 3.38%. Among reported serious adverse events in this batch, there were 14 respiratory failure, 11 thrombosis, 7 myocarditis, 6 pericarditis, 5 cardiac arrest, 5 myocardial infarction, and 4 pulmonary embolism reports (

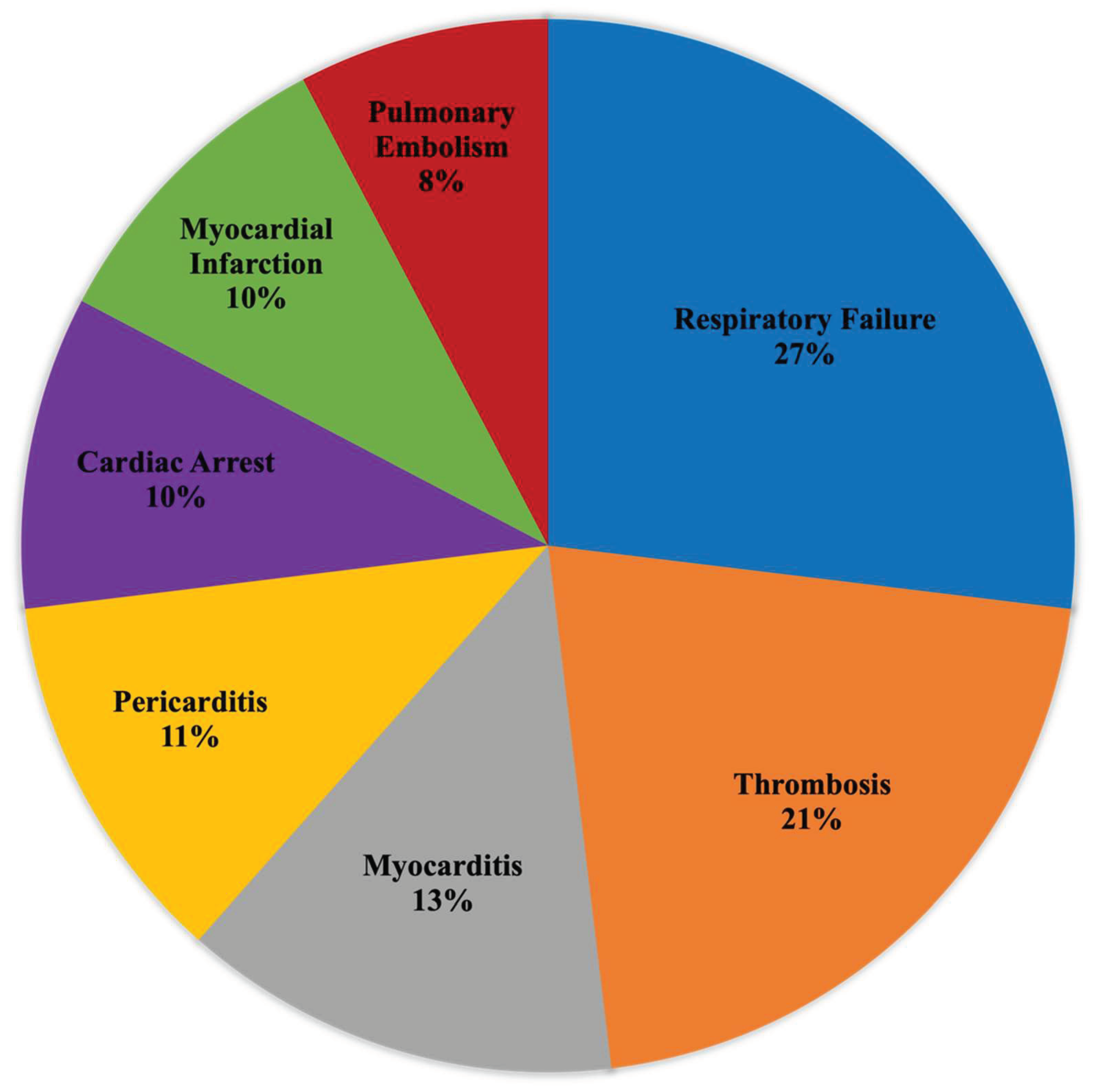

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of common serious adverse events linked to COVID-19 vaccine batch EW0175 as reported in the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).

Figure 2.

Proportion of common serious adverse events linked to COVID-19 vaccine batch EW0175 as reported in the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).

Autopsy Checklist

Without proper post-mortem investigation into specific COVID-19 vaccine components residing in blood and tissues, it is difficult to confidently determine the cause of death in COVID-19 vaccinated subjects that present anomalous symptoms, as in our case. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the potential impact of COVID-19 vaccines on adverse fatal outcomes, it is critical to conduct a thorough evaluation that includes testing for the presence of the Spike protein and vaccine-derived mRNA within tissue samples. Additionally, a detailed antibody profile should be established, including tests for antibodies against platelet factor 4 (anti-PF-4), the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, the nucleocapsid component of the virus, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Alongside these tests, an assessment of inflammation specific to various organs is necessary. These combined diagnostic efforts can reveal how the vaccine may contribute to unexpected fatal events [11-12], especially since most autopsies performed following COVID-19 vaccination don’t include them [

13]. Thus, we propose an autopsy checklist for deceased individuals that have received one or more COVID-19 vaccines (

Table 1).

Discussion

Cause of death is always a matter of expert analysis and cases like this deserve a second opinion. A standard methodology applied to post-mortem investigations is differential diagnosis [

14]. Despite having coronary atherosclerosis, the vessels were patent and there was no myocardial infarction. The left ventricle was not hypertrophied nor dilated, so longstanding hypertension or heart failure can be excluded. Primary gastrointestinal and cerebral hemorrhage was excluded. The patient appeared to have died from acute pulmonary hemorrhage a few days after a viral infection. Primary pulmonary hemorrhage can occur in auto-immune syndromes including Goodpasture’s syndrome [

15] and Wegener’s granulomatosis [

16]. The hemorrhage was rapid and quickly made the patient hypoxemic, thus creating a secondary cardiac arrest given extensive coronary disease. The reports of copious blood coming from the patient requiring suctioning and tranexamic acid are distinctly unusual for a primary cardiac arrest. Importantly, the coronary disease does not appear to be the primary cause of death but there is no plaque rupture reported, nor evidence of myocardial infarction. Multiple ecchymoses and a lack of response to tranexamic acid suggests impaired coagulation from a variety of sources including thrombocytopenia. It is reasonable to conclude that primary pulmonary hemorrhage or secondary hemorrhage from acute pulmonary edema in a perfectly healthy man after a viral respiratory illness is quite anomalous. Von Ranke et al summarized the range of upper respiratory infections that can result in diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, which include influenza A (H1N1), dengue, leptospirosis, malaria, and

Staphylococcus aureus infection [

17]. None of these diseases fits the presentation or time course of this patient’s mild 3-day viral illness. He had no travel history, fever, or productive cough. His upper respiratory pathogen panel was negative.

Primary pulmonary hemorrhage can occur after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination [5-7]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) regulatory window of concern for a novel genetic product, such as the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, is 5-15 years [

18]. That means unusual serious adverse events such as fatal pulmonary hemorrhage should not only be reported to VAERS, but also be considered as being a consequence of the novel product even months to years after the last injection. The COVID-19 vaccine batch EW0175 that this patient received has been associated with cardiovascular, hematological, and respiratory adverse events and exhibits a high degree of lethality compared to most batches. The Spike protein produced from COVID-19 vaccine mRNA is known to cause bleeding, thrombosis and specific hemorrhagic-thrombotic syndromes including vaccine induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) which has been reported after the Pfizer vaccine [19-21]. The majority of VITT cases arising from vaccine induced anti-platelet factor-4 antibodies reported in the literature are caused by the adenoviral vector vaccines, however, “long VITT” has been reported where findings last for months after vaccine administration [22-23]. It is possible that any mild viral upper respiratory infection in a mRNA COVID-19 vaccinated patient could result in acute hemorrhage. The systemic circulation and extensive persistence (>4 months) of Spike protein from COVID-19 vaccination likely accelerated asymptomatic coronary atherosclerosis, pulmonary capillary disease, and alveolar inflammation as summarized by Parry et al [

11]. However, our proposed autopsy checklist would have significancy improved the diagnostic accuracy in this case and in many other reported autopsies following COVID-19 vaccination [12-13].

In conclusion, this man died of a cardiopulmonary arrest most likely as a result of acute pulmonary hemorrhage. The coronary artery disease was coincident but was not the primary cause of the cardiac arrest. Because the autopsy ruled out other possible causes of death, prior COVID-19 vaccination is potentially either the direct cause or contributed to the causal pathway leading to death. Additionally, COVID-19 vaccine-induced Spike protein may have caused acceleration of asymptomatic coronary atherosclerosis via direct vessel injury and inflammation. Our recommendation for a specialized autopsy approach can help improve the diagnosis of COVID-19 vaccine-induced pathologies in future cases.

Author Contributions

Nicolas Hulscher and Peter A. McCullough: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not applicable for this study, because no IRB approval is required for autopsy case reports as long as informed consent was obtained from the next of kin of the deceased individual and all data has been anonymized.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the next of kin for the deceased individual included in this case report.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kalinke U, Barouch DH, Rizzi R, Lagkadinou E, Türeci Ö, Pather S, Neels P. Clinical development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022 May;21(5):609-619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [online]. World Health Organization; Available at: https://covid19.who.int/.

- Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) [online]. Available at: https://vaers.hhs.gov.

- Schmeling M, Manniche V, Hansen PR. Batch-dependent safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023 Aug;53(8):e13998. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rasbi S, Al-Maqbali JS, Al-Farsi R, Al Shukaili MA, Al-Riyami MH, Al Falahi Z, Al Farhan H, Al Alawi AM. Myocarditis, Pulmonary Hemorrhage, and Extensive Myositis with Rhabdomyolysis 12 Days After First Dose of Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2022 Feb 17;23:e934399. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishioka K, Yamaguchi S, Yasuda I, Yoshimoto N, Kojima D, Kaneko K, Aso M, Nagasaka T, Yoshida E, Uchiyama K, Tajima T, Yoshino J, Yoshida T, Kanda T, Itoh H. Development of Alveolar Hemorrhage After Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination in a Patient With Renal-Limited Anti-neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis: A Case Report. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Apr 8;9:874831. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma A, Upadhyay B, Banjade R, Poudel B, Luitel P, Kharel B. A Case of Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage With COVID-19 Vaccination. Cureus. 2022 Jan 27;14(1):e21665. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matoba K, Hyodoh H, Murakami M, Saito A, Matoba T, Ishida L, Fujita E, Yamase M, Jin S. Estimating normal lung weight measurement using postmortem CT in forensic cases. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2017 Nov;29:77-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westaby JD, Zullo E, Bicalho LM, Anderson RH, Sheppard MN. Effect of sex, age and body measurements on heart weight, atrial, ventricular, valvular and sub-epicardial fat measurements of the normal heart. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2023 Mar-Apr;63:107508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoll, F. How Bad is My Batch? [Online]. GitHub; 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 17]. Available at: https://knollfrank.github.io/HowBadIsMyBatch/HowBadIsMyBatch.html.

- Parry PI, Lefringhausen A, Turni C, Neil CJ, Cosford R, Hudson NJ, Gillespie J. 'Spikeopathy': COVID-19 Spike Protein Is Pathogenic, from Both Virus and Vaccine mRNA. Biomedicines. 2023 Aug 17;11(8):2287. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulscher N, Hodkinson R, Makis W, McCullough PA. Autopsy findings in cases of fatal COVID-19 vaccine-induced myocarditis. ESC Heart Fail. 2024 Jan 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulscher N, Alexander PE, Amerling R, Gessling H, Hodkinson R, Makis W, Risch H, Trozzi M, McCullough PA. A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF AUTOPSY FINDINGS IN DEATHS AFTER COVID-19 VACCINATION. Zenodo. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jain, B. The key role of differential diagnosis in diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl). 2017 Nov 27;4(4):239-240. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVrieze BW, Hurley JA. Goodpasture Syndrome. 2022 Sep 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. [PubMed]

- Mahajan V, Whig J, Kashyap A, Gupta S. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in Wegener's granulomatosis. Lung India. 2011 Jan;28(1):52-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Ranke FM, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, Marchiori E. Infectious diseases causing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in immunocompetent patients: a state-of-the-art review. Lung. 2013 Feb;191(1):9-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long Term Follow-Up After Administration of Human Gene Therapy Products [Internet]. FDA; 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/113768/download.

- Grandone E, Chiocca S, Castelvecchio S, Fini M, Nappi R; representatives for Gender Medicine of Scientific Hospitalization and Treatment Institutes-Italian Ministry of Health(the collaborators are listed in the Appendix 1). Thrombosis and bleeding after COVID-19 vaccination: do differences in sex matter? Blood Transfus. 2023 Mar;21(2):176-184. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Michele M, d'Amati G, Leopizzi M, Iacobucci M, Berto I, Lorenzano S, Mazzuti L, Turriziani O, Schiavo OG, Toni D. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on retrieved thrombi from COVID-19 patients. J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Aug 16;15(1):108. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin TC, Fu PA, Hsu YT, Chen TY. Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia following BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Booster: A Case Report. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Jun 19;11(6):1115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberge G, Carrier M. Long VITT: A case report. Thromb Res. 2023 Mar;223:78-79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther A, Brämer D, Pletz MW, Kamradt T, Baumgart S, Mayer TE, Baier M, Autsch A, Mawrin C, Schönborn L, Greinacher A, Thiele T. Complicated Long Term Vaccine Induced Thrombotic Immune Thrombocytopenia-A Case Report. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Nov 17;9(11):1344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).