Submitted:

20 February 2024

Posted:

20 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

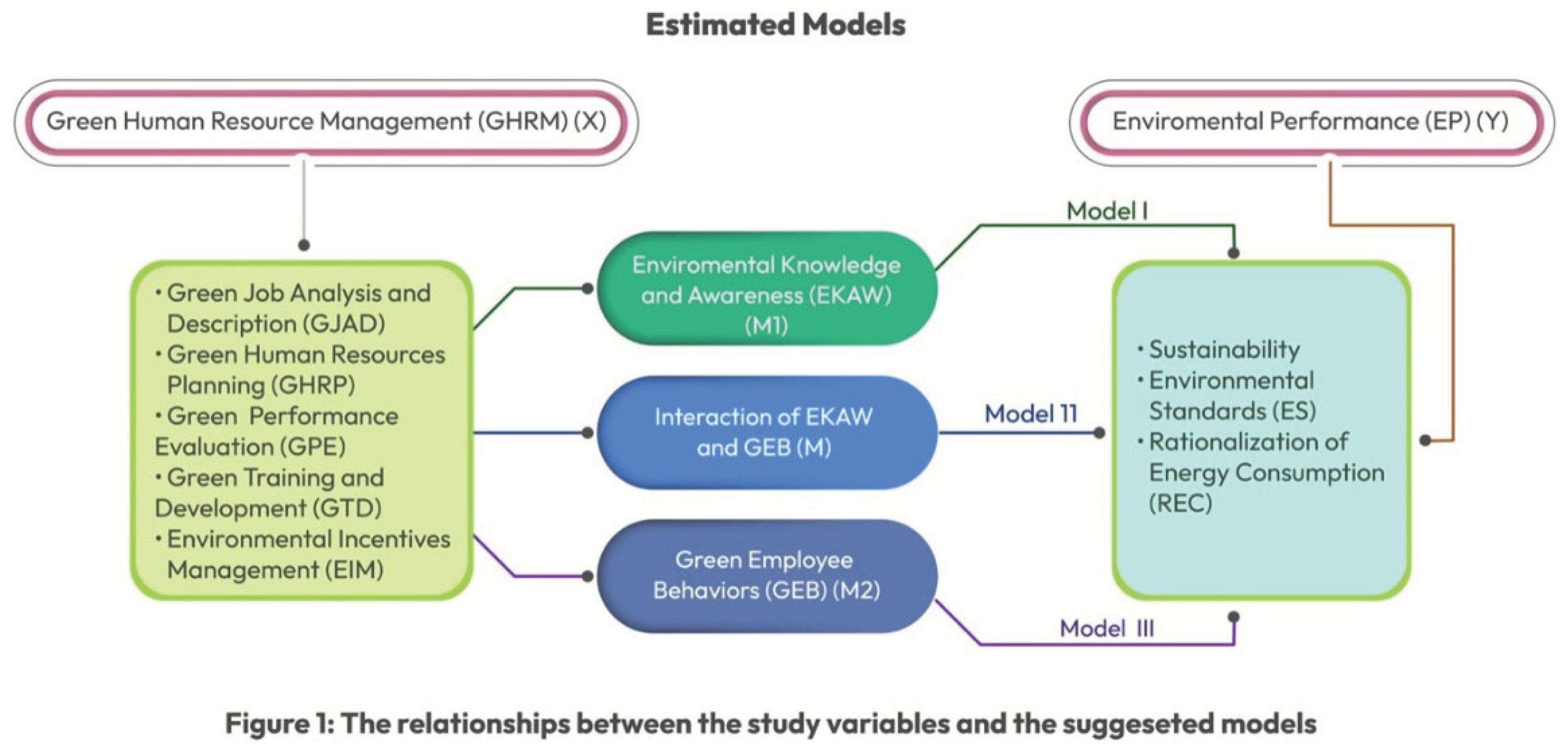

- To evaluate how Green HRM affects environmental performance.

- To examine the mediating role of green employee behaviors and environmental awareness on environmental performance.

- To determine Green HRM strategies’ degree of success.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Applied Organizational Theories

2.1. Green HRM

2.2. Green Employee Behavior

Top of Form

2.3. Environmental Knowledge and Awareness

2.4. Environmental Performance

Literature Gap and Hypotheses

- -

- A statistically significant relation exists between Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Performance through the mediator variable Environmental Knowledge and Awareness.

- -

- A statistically significant relation exists between Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Performance through the mediator variable Green Employee Behaviors.

- -

- A statistically significant relation exists between Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Performance through interaction between the mediator variables Environmental Knowledge and Awareness and Green Employee Behaviors.

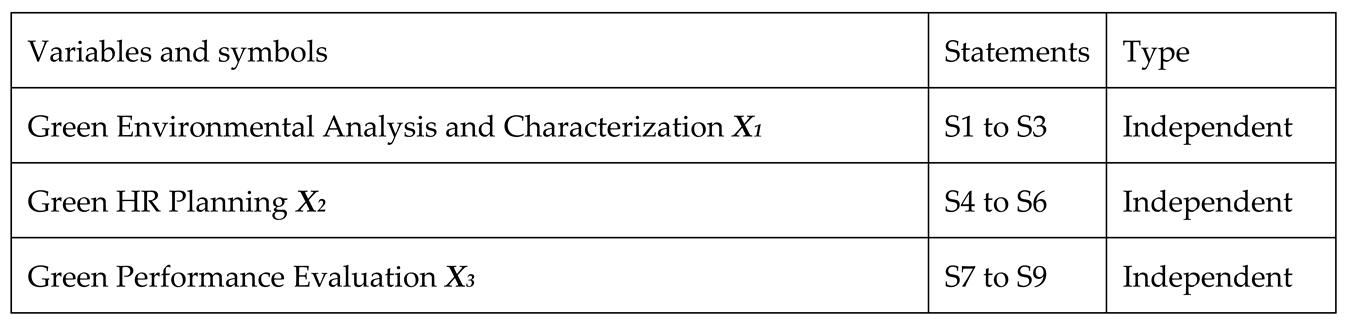

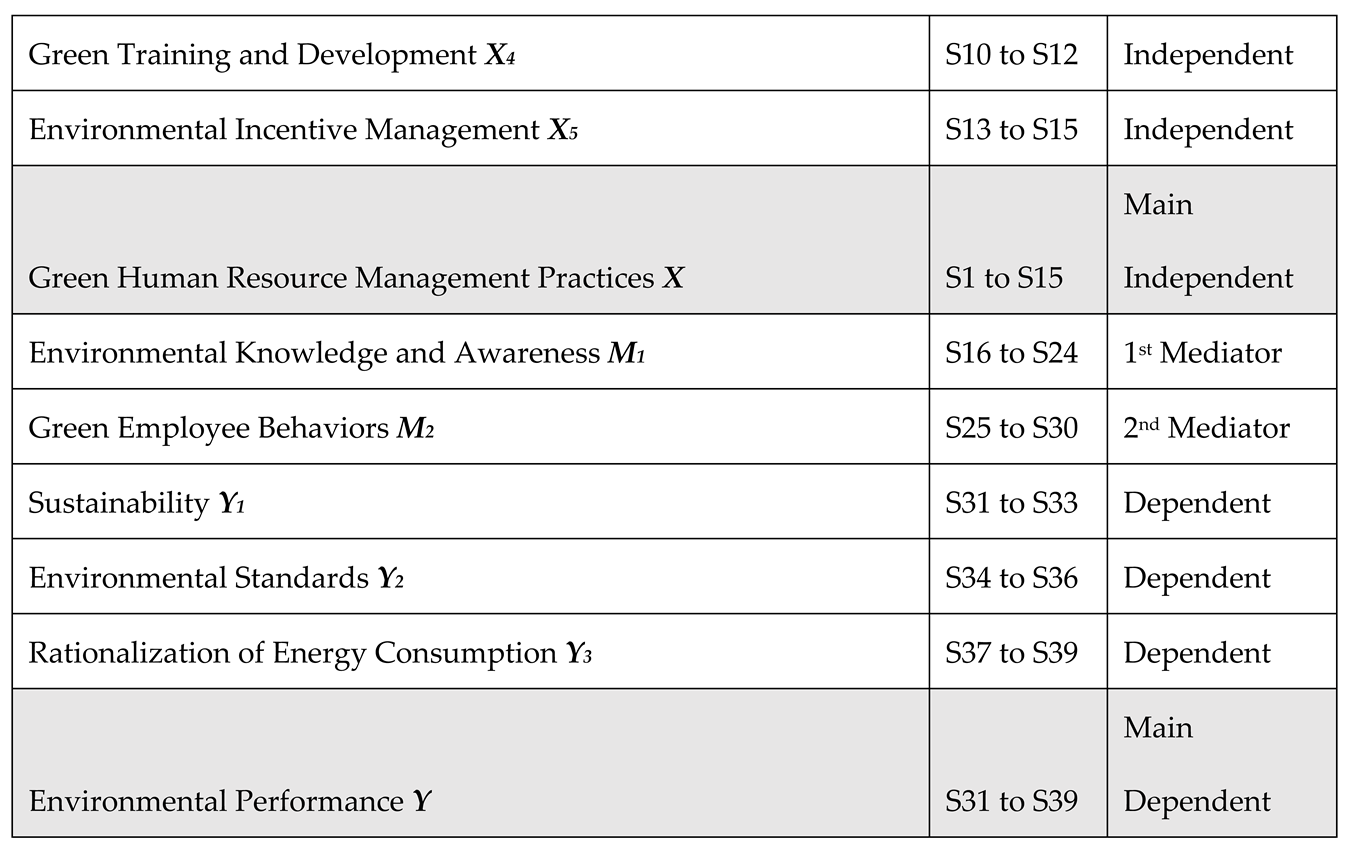

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Measures

3.2. Sample

3.3. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

- -

- Cronbach’s alphas were used to verify the stability and reliability of the expressions for each variable in the whole data set.

- -

- Tests of normality were conducted for each study variable.

- -

- The diagnostic tool Pearson correlation coefficient was used to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between each pair of variables.

- -

- Multiple regression models were applied to estimate the best model to explain the data effectively.

3.3.1. Reliability and Validity Test

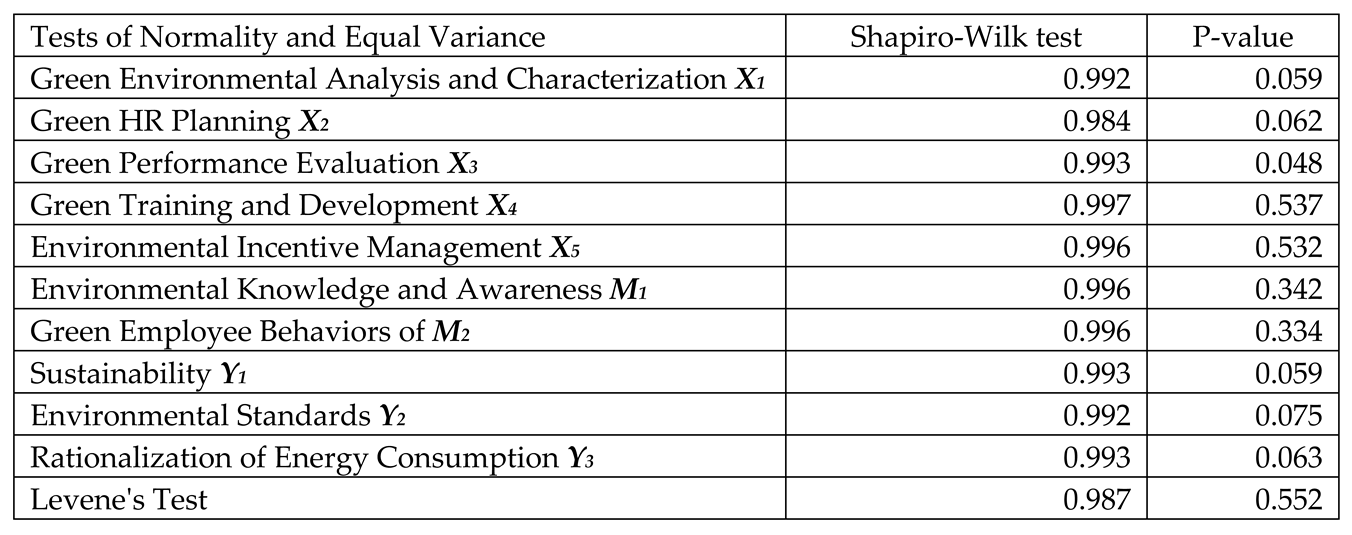

3.3.2. Test of Normality

- Normality: The data in each group should be distributed normally (Shapiro-Wilk test).

- Equal Variance: The data in each group should have equal variance (Levene’s test).

3.3.3. Test of Hypotheses

| Dependent Variables/Moderate Variables | Environmental Knowledge and Awareness M1 | Green Employee Behavior M2 | |

| Sustainability Y1 | R | 0.410 | 0.556 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Environmental Standards Y2 | R | 0.205 | 0.207 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Rationalization of Energy Consumption Y3 | R | 0.221 | 0.174 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Variables | GHRM X | EKAW M1 | GEB M2 | |

| EKAW M1 | r | 0.653 | ||

| Sig. | 0.000 | |||

| GEB M2 | r | 0.675 | -0.063 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.207 | ||

| EP Y | r | 0.921 | 0.635 | 0.622 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

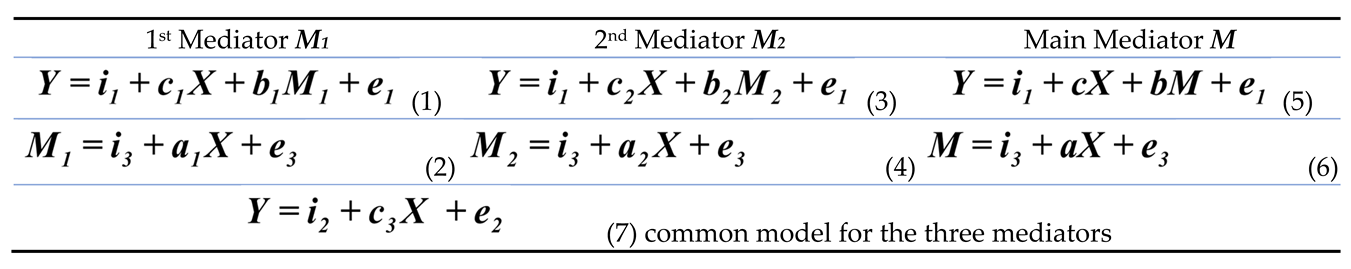

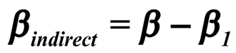

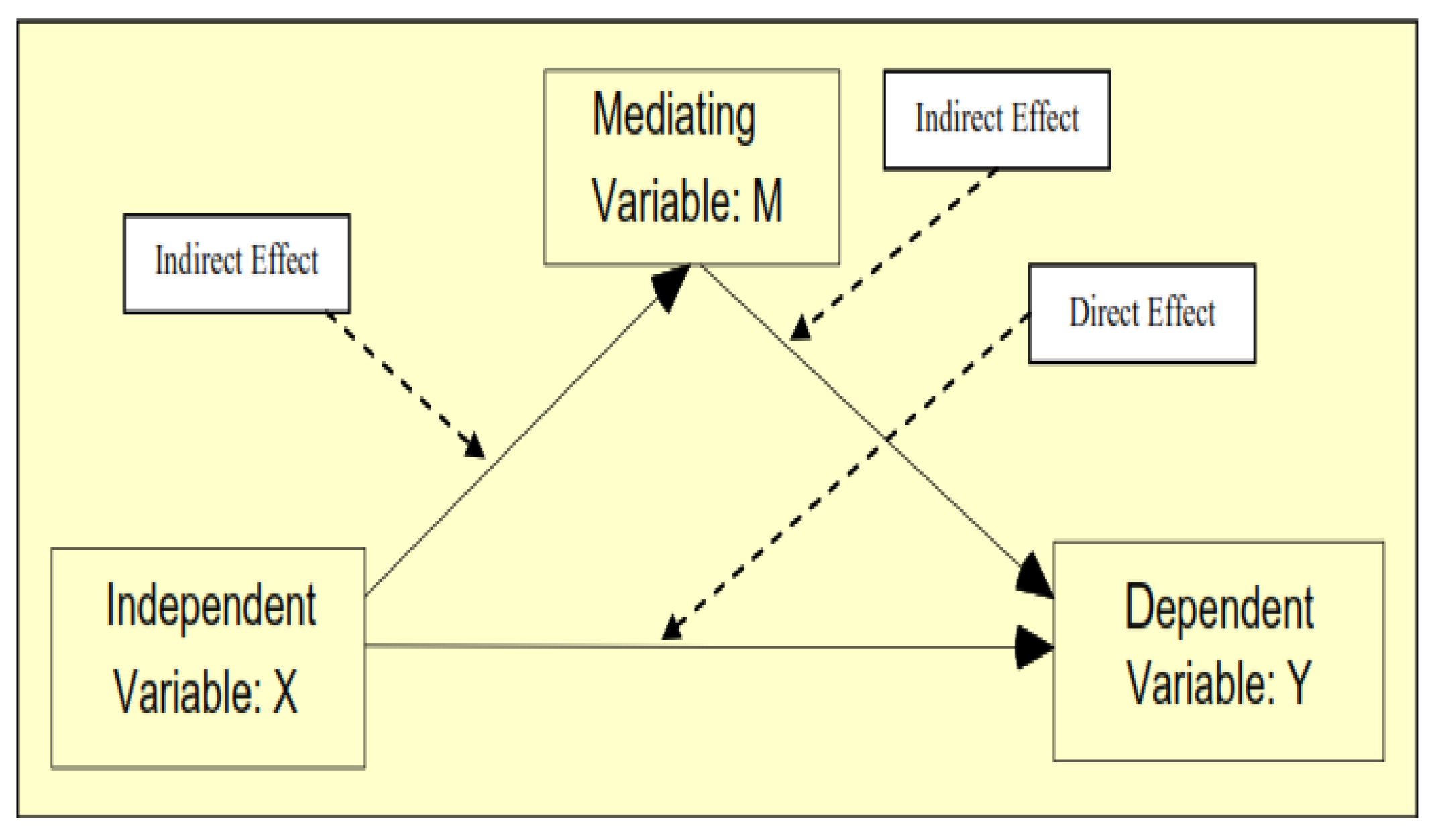

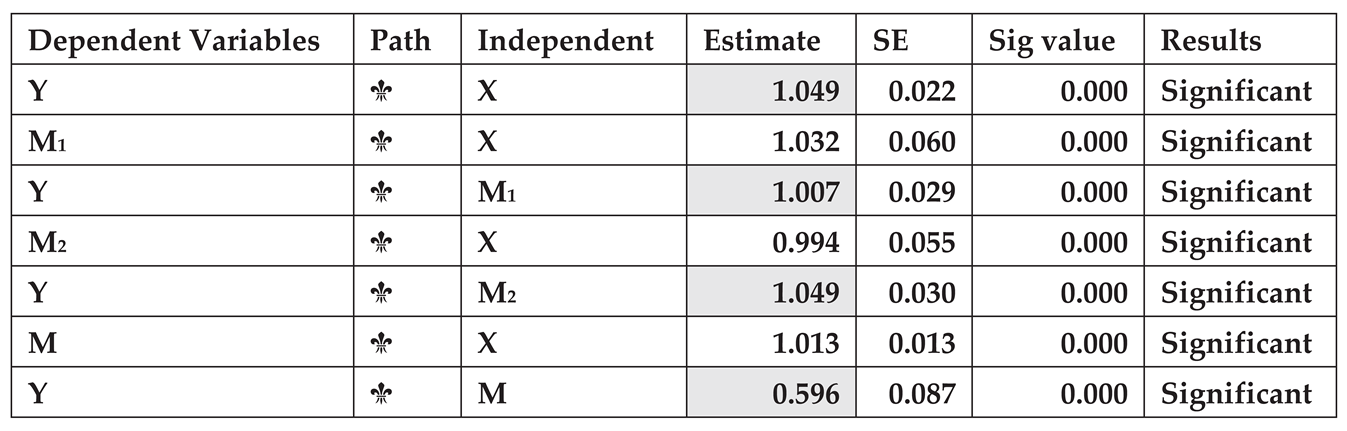

3.3.4. Testing Mediation with Regression Analysis

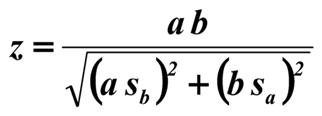

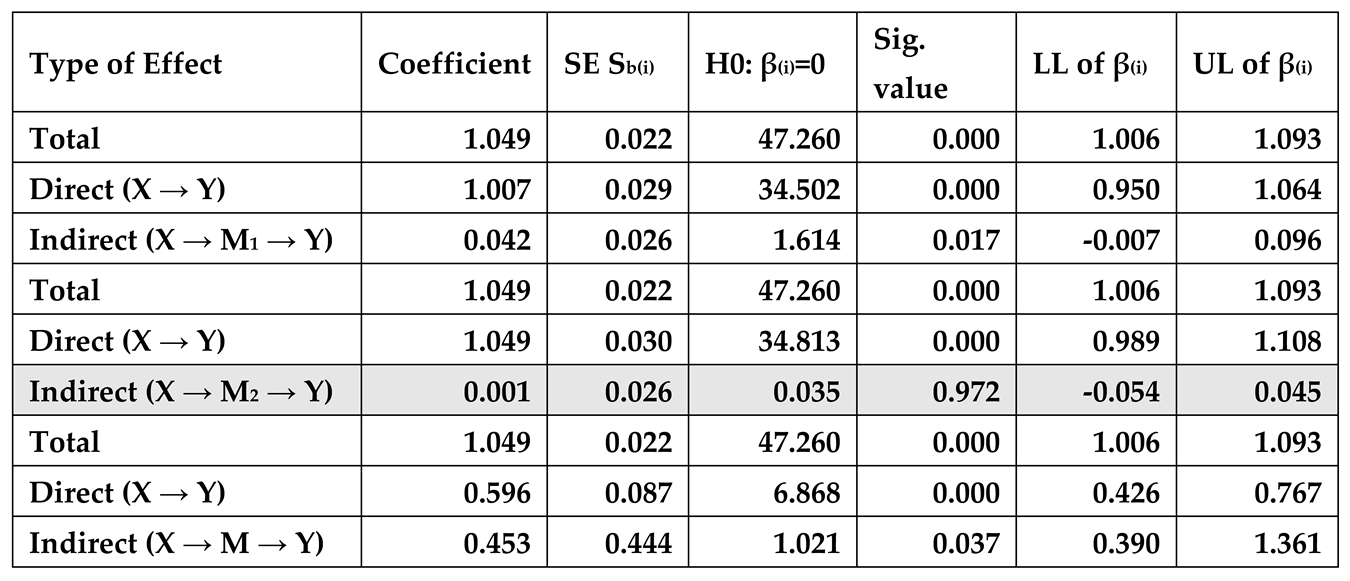

3.3.5. Testing the Mediated Effect

3.1.6. Bootstrapping

- (1)

- Judd and Kenny’s (1993) approach

- (2)

- Sobel (1982) product approach

- -

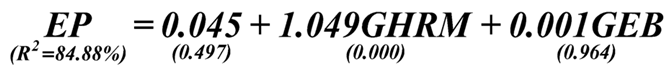

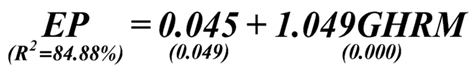

- Model 7: A confidence interval of 95% was detected, indicating that the main independent variable, GHRM (X), significantly affects the main dependent variable, EP (Y ), as the coefficient of determination reached 84.90%, and this model’s Sig. value was smaller than 0.050.

- -

- Model 1: The first mediator variable, EKAW (M1), was added in this model, which is still significant, with Sig. values of 0.000 and 0.027 for each variable smaller than 0.050. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination for the main independent variable, GHRM (X), reached 44.80%, and for EKAW (M1), 0.20%. One can conclude that the first mediator variable, EKAW (M1), directly affected the dependent variable, EP( Y ).

- -

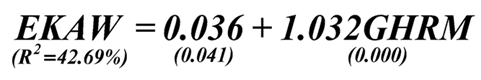

- Model 2: Statistical evidence with a confidence interval of 95% was found, indicating that the first mediator variable, EKAW (M1), significantly affected the main independent variable GHRM (X), as the coefficient of determination reached 42.70%, and this model’s Sig. value was smaller than 0.050.

- -

- Model 3: The second mediator variable, GEB (M2), was added in this model. The Sig. value of the GEB (M2) was 0.964, greater than 0.050, so this variable did not affect the dependent variable, EP, (Y). Furthermore, the coefficient of determination for the main independent variable, GHRM (X), reached 46.20%, and for GEB (M2), 00%. One can conclude that the second mediator variable did not affect the dependent variable, (EP) Y .

- -

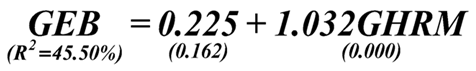

- Model 4: This model represents the effect of GHRM (X) (IV) on the second mediator variable, GEB (M2) (DV). This model is significant because the Sig. value is smaller than 0.050, and the coefficient of determination reached 45.50%. Thus, a significant relationship was found between GHRM (X) and GEB (M2).

- -

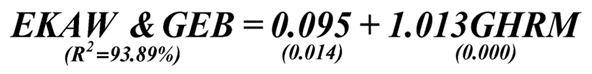

- Model 5: This model represents the effect of the main independent variable, GHRM (X), and the main mediator variable, EKAW & GEB (M), on the main dependent variable, EP (Y ). The model is still significant, and the Sig. values were 0.000 and 0.000, respectively, with each variable smaller than 0.050. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination of the main independent variable, GHRM (X), reached 1.70% and 84.24% for EKAW and GEB (M), respectively. One can conclude that the main mediator variable exerts a direct effect on the dependent variable, EP (Y ).

- -

- Model 6: This model represents the effect of EKAW and GEB (M) on EP (Y ). Statistical evidence with a confidence interval of 95% was found, indicating that the main mediator variable, M, significantly affects the main dependent variable, EP (Y ), as the coefficient of determination reached 93.90% and the Sig. value of this model was smaller than 0.050.

- In the first step, the researchers begin by modeling the simple effect of GHRM (X) on EP (Y) (Model 7).

- In the second step, they entered the first mediator variable, EKAW (M1), into the model to test the direct effect of GHRM (X) on EP (Y) (Model 1).

- The third step estimated the simple effect of GHRM (X) on the first mediator variable, EKAW (M1).

- The second and third steps were repeated for the second and main mediator variables.

4. Discussion

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Disclosure statement

References

- Ababneh, O.M.A. How do green HRM practices affect employees’ green behaviors? The role of employee engagement and personality attributes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2021, 64, 1204–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M. The effect of green HRM on employee green behaviors in higher education: the mediating mechanism of green work engagement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 2022, 30, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, M.; Mahmood, S.; Khan, K.I.; Saleem, S. Green HR practices and environmental performance: The mediating mechanism of employee outcomes and moderating role of environmental values. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 1001100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Green human resource management: Policies and practices. Cogent business & management 2015, 2, 1030817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, E.; Karatepe, O.M.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Avci, T. A conceptual model for green human resource management: Indicators, differential pathways, and multiple pro-environmental outcomes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad Al-Shammari, A.S.; Alshammrei, S.; Nawaz, N.; Tayyab, M. Green human resource management and sustainable performance with the mediating role of green innovation: A perspective of new technological era. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 901235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Schaltegger, S. Pragmatism and new directions in social and environmental accountability research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 2015, 28, 263–294. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The mediator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.E.; Huselid, M.A. Strategic human resources management: where do we go from here? Journal of management 2006, 32, 898–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, U.; Lopatka, A.; Devkota, N.; Paudel, U.R.; Németh, P. Influence of green human resource management on employees' behavior through mediation of environmental knowledge of managers. Journal of International Studies 2023, 16, 2071–8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé; P; Raineri, N. The nature of employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. The psychology of green organizations 2015, 12–32.

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Green human resource management as a tool for the sustainable development of enterprises: Polish young company experience. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green human resource management and employee green behavior: an empirical analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Heyer, S.; Ibbotson, S.; Salonitis, K.; Steingrímsson, J.G.; Thiede, S. Direct digital manufacturing: definition, evolution, and sustainability implications. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 107, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z. How to facilitate employees’ green behavior? The joint role of green human resource management practice and green transformational leadership. Frontiers in psychology 2022, 13, 906869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.J. Hotels' environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tourism management 2014, 40, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Govindarajulu, N. A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Business & Society 2009, 48, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Green HRM, environmental awareness and green behaviors: The moderating role of servant leadership. Tourism Management 2022, 88, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Donaldson, L. Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review 1997, 22, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, P. Green HRM: An organizational strategy of greening people. International Journal of applied research 2015, 1, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Human resource management 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. (1993) An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall, New York.

- Ehnert, I.; Ehnert, I. (2009). Sustainable human resource management. Physica-Verlag.

- Elkington, J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California management review 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R.; Yuthas, K. Implementing sustainability: The role of leadership and organizational culture. Strategic finance 2010, 91, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Mohamad, Z.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. Assessing the green behaviour of academics: The role of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. International Journal of Manpower 2020, 41, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, G.C.; Ooi, S.K.; Teoh, S.T.; Lim, H.L.; Yeap, J.A. Green human resource management, leader–member exchange, core self-evaluations and work engagement: the mediating role of human resource management performance attributions. International Journal of Manpower 2022, 43, 682–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T.S. Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Academy of Management Review 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, R.; Rehman, N.; Tufail, S. Green human resource management and environmental knowledge: A moderated mediation model to endorse green CSR. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Naeem, R.M. Do green HRM practices influence employees' environmental performance? International Journal of Manpower 2020, 41, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping, 127, 147.

- Hristova, S.; Stevceska-Srbinovska, D. (2020). Green HRM in pursuit of sustainable competitive advantage.

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Green human resource management and green supply chain management: Linking two emerging agendas. Journal of cleaner production 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, A.; Cafferkey, K.; Townsend, K. (2019). 21. Ability, Motivation and Opportunity theory: a formula for employee performance?. Elgar introduction to theories of human resources and employment relations, 311.

- Kwatra, S.; Pandey, S.; Sharma, S. Understanding public knowledge and awareness on e-waste in an urban setting in India: A case study for Delhi. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2014, 25, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Yeung, A.C.; Cheng, T.C.E. The impact of environmental management systems on financial performance in fashion and textiles industries. International journal of production economics 2012, 135, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, R.; McIvor, J.; O'Brien, M.; Wright, C.F. Reducing carbon emissions through employee participation: evidence from Australia. Industrial Relations Journal 2019, 50, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel psychology 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organization & Environment 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Paillé, P.; Valéau, P.; Renwick, D.W. Leveraging green human resource practices to achieve environmental sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 260, 121137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Jabbour, C.J.; Muller-Camen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2016, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green HRM: A review, process model, and research agenda. University of Sheffield Management School Discussion Paper 2008, 1, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. (2013), “Green human resource management: a review.

- Sabokro, M.; Masud, M.M.; Kayedian, A. The effect of green human resources management on corporate social responsibility, green psychological climate and employees’ green behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 313, 127963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifulina, N.; Carballo-Penela, A.; Ruzo-Sanmartín, E. Sustainable HRM and green HRM: The role of green HRM in influencing employee pro-environmental behavior at work. Journal of Sustainability Research 2020, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, C.; Haddock-Millar, J. (2018). 3 Employee engagement in managing environmental performance. Contemporary Developments in Green Human Resource Management Research: Towards Sustainability in Action?

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Integrative management of sustainability performance, measurement and reporting. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation 2006, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Dumont, J.; Deng, X. Retracted: Employees’ perceptions of green HRM and non-green employee work outcomes: The social identity and stakeholder perspectives. Group & Organization Management 2018, 43, 594–622. [Google Scholar]

- Shipton, H.; Budhwar, P.S.; Crawshaw, J. HRM, organizational capacity for change, and performance: A global perspective. Thunderbird International Business Review 2012, 54, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of environmental psychology 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: scale development and validity. Asia pacific journal of human resources 2018, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Robertson, J.L. How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. ethics 2019, 155, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtenberg, J.; Harmon, J.; Russell, W.G.; Fairfield, K.D. (2007), “HR’s role in building a sustainable.

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. Journal of management 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Fawehinmi, O.O. Green human resource management: A systematic literature review from 2007 to 2019. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2020, 27, 2005–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How green human resource management can promote green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. The influence of green human resource management on employee green behavior—a study on the mediating effect of environmental belief and green organizational identity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadat, A.H. Major factors contributing to environmental awareness among people in a third world country/Jordan. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2010, 12, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. Journal of cleaner production 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Variables and Symbols | Cronbach's Alpha | Validity |

| Green Environmental Analysis and Characterization X1 | 0.978 | 0.989 |

| Green HR Planning X2 | 0.980 | 0.990 |

| Green Performance Evaluation X3 | 0.977 | 0.989 |

| Green Training and Development X4 | 0.978 | 0.989 |

| Environmental Incentive Management X5 | 0.978 | 0.989 |

| Green Human Resource Management Practices X (Main independent) | 0.978 | 0.989 |

| Environmental Knowledge and Awareness M1 | 0.989 | 0.995 |

| Green Employee Behaviors M2 | 0.989 | 0.995 |

| Sustainability Y1 | 0.977 | 0.989 |

| Environmental Standards Y2 | 0.978 | 0.989 |

| Rationalization of Energy Consumption Y3 | 0.977 | 0.989 |

| Environmental Performance Y (Main Dependent) | 0.977 | 0.989 |

| Minimum Value | 0.977 | 0.989 |

|

| Independent Variables/Mediator Variables |

Environmental Knowledge and Awareness M1 | Green Employee Behaviors M2 |

|

| Green Environmental Analysis and Characterization X1 |

R | 0.354 | 0.378 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Green HR Planning X2 | R | 0.339 | 0.435 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Green Performance Evaluation X3 |

R | 0.398 | 0.374 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Green Training and Development X4 |

R | 0.402 | 0.431 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Environmental Incentive Management X5 |

R | 0.641 | 0.537 |

| Sig. Value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Models | Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | R2 | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7: Y = f(X) | Y | GHRM (X) | 84.90% | 0.000 |

| Model 1: Y = f(X, M1) | Y | GHRM (X) | 44.80% | 0.000 |

| EKAW (M1) | 0.20% | 0.027 | ||

| Model 2: M1 = f(X) | EKAW (M1) | GHRM (X) | 42.70% | 0.000 |

| Model 3: Y = f(X, M2) | Y | GHRM (X) | 46.20% | 0.000 |

| GEB (M2) | 0.00% | 0.964 | ||

| Model 4: M2 = f(X) | GEB (M2) | GHRM (X) | 45.50% | 0.000 |

| Model 5: Y = f(X, M) | Y | GHRM (X) | 1.70% | 0.000 |

| EKAW & GEB (M) | 84.24% | 0.000 | ||

| Model 6: M = f(X) | EKAW & GEB (M) | GHRM (X) | 93.90% | 0.000 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).