1. Introduction

Dysmenorrhea is a common menstrual complaint affecting 16-91% of women of reproductive age; dysmenorrhea-associated severe pain is present in 2-29% [

1]. A positive family history, an age younger than 30 years, menarche younger than 12 years, a longer menstrual cycle, a heavy menstrual flow, a nulliparous status, obesity, smoking, high stress levels, and a history of sexual abuse are risk factors for dysmenorrhea [

1,

2,

3]. Protective factors include increasing age, parity, exercise, and use of oral contraceptives. Dysmenorrhea can be a symptom of endometriosis.

Dysmenorrhea is typically described as cramping pain in the lower abdomen starting at the onset of menstrual flow and often lasting 8-72 h; frequent accompanying symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, muscle cramps, lower back pain, fatigue and, particularly with severe dysmenorrhea, sleep disturbance [

2,

3]. For instance, a cross-sectional study of 408 young women reported menstrual pain in 84% of participants with more than half reporting the occurrence of pain during each period [

4]. Thus, dysmenorrhea is one of the most common causes of pelvic pain and has an adverse impact on quality of life, work productivity, absenteeism, and health care utilization [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6].

Guideline-recommended medical management options include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives [

2,

3]. While hormonal contraceptives are prescription drugs in most countries, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often available without a prescription as over-the-counter (OTC) products enabling women to self-manage their condition. Accordingly, many women (36-70%) manage their dysmenorrhea by self-medication often involving mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, or paracetamol [

7,

8].

Hyoscine butylbromide (HBB; also known as butylscopolamine bromide or as scopolamine butylbromide) is a well-established anti-spasmodic medicine [

9] that has also shown efficacy in a mouse model of dysmenorrhea [

10]. A fixed-dose combination of HBB plus paracetamol (a.k.a. acetaminophen), hereafter referred to as PLUS, is approved for the treatment of dysmenorrhea-associated cramps and pain in 10 countries including Austria, Chile, Germany, Greece, Indonesia, Italy, Korea, Philippines, Portugal, and Türkiye.

Following several open-label studies in women with dysmenorrhea applying HBB in combination with metamizole [

11], HBB alone [

12], or HBB in combination with lysine clonixinate [

13], 125 women with dysmenorrhea were randomized to cross-over treatment with HBB plus paracetamol, lysine clonixenate plus propinox, or placebo in a double-blind trial with each treatment phase starting three days before onset of menses and lasting for five days thereafter [

14]. Both active treatments reduced pain relative to placebo with HBB plus paracetamol numerically causing the greatest reduction.

A recent pharmacy-based patient survey (PBPS) evaluated three preparations for the treatment of abdominal cramps and pain in 1686 patients [

15]; this included 329 women reporting the use of PLUS for dysmenorrhea. Here we characterize these women and the self-reported effect of PLUS in an exploratory, secondary analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

Details of study design and tested products have been reported [

15]. Briefly, a non-interventional, prospective PBPS was performed among patients who had purchased PLUS (Buscopan plus

®). The questionnaire included a question on the indication for which PLUS was used with the options of “abdominal cramps and pain”, “urinary complaints such as urinary tract infection”, “dysmenorrhea”, and “other” with multiple nominations being possible. This manuscript focuses on the subgroup of 329 women reporting to have used PLUS for the indication of dysmenorrhea, regardless of additional indications being stated.

Inclusion criteria of the primary study [

15] were the purchase of the product, willingness and ability to fill out the paper-based questionnaire, and an age of ≥18 years. There were no prespecified exclusion criteria in the main study. However, we excluded 13 women from the analysis because they had either an age <18 years (n = 3) or >51 years (n = 10; post-hoc decision). The younger three were excluded because of not meeting the inclusion criteria and the older 10 because we considered their age as implausible regarding the self-reported diagnosis of dysmenorrhea based on an upper end of 51 years for the 95% confidence interval for onset of menopause [

16]; an additional two women did not provide age data, leaving 314 women for analysis.

The survey was anonymous, and no information was collected allowing post hoc identification or contact of the participants. Applicable German laws and regulations neither required nor recommended the involvement of an ethical committee for an anonymous survey at the time when it was conducted; this is in line with other recently reported PBPS from Germany [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The questionnaires included questions on demographic variables (gender, age), number of days with symptoms in the past 30 days, the perceived trigger of the current complaints (selection from a list of possible triggers), and the time span of pain/complaints before treatment initiation, i.e., proposing the categories “first signs of a ‘bad day’”, “directly” and 30 min, 60 min, 2 h, or more than 2 h after onset of symptoms. The current condition was described by asking questions on the intensity of pain/complaints prior to first ingestion of the medication and on their impact on work/daily chores, leisure activities, and sleep. The questions on the severity of pain/complaints and on associated impact were rated on an 11-point Likert scale (0–10 from no to very strong pain/complaint/impact); all other questions were asked categorically. The questions on the intensity of pain/complaint and the impact of the current condition were repeated after drug intake. The questionnaires asked about the onset of relief following first ingestion with available options of 0–5, 6–15, 16–30, 31–45, 46–60, and >60 min. Finally, perceived general effectiveness, tolerability, and treatment satisfaction were captured.

Data are reported as means ± SD and as medians with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous parameters and in absolute numbers and % of total for categorical parameters. All analyses reported in the primary publication have now been performed for the women reporting the use of the product for the treatment of dysmenorrhea symptoms. In line with recent guidelines for enhanced robustness of data analysis [

22,

23], we considered all data exploratory, i.e., not testing a prespecified statistical null hypothesis. Therefore, as recommended by leading statisticians [

24], we do not report p-values and focus on effect sizes with the presentation of 95% CI.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Baseline Patient Characteristics

The participants had a mean age of 32.3 ± 9.2 years (IQR 25-40 years). Concomitant abdominal cramps and pain, urinary tract complaints, and “other” were reported by 98, 18, and 11 women (31.2%, 5.7%, and 3.5%, respectively). The mean and median number of days within the past month with such concomitant complaints was 4.34-4.54 and 2-3, respectively (

Table 1). Of note, data on bloating and flatulence are difficult to interpret as 90 and 102 women, respectively, had missing data for these parameters.

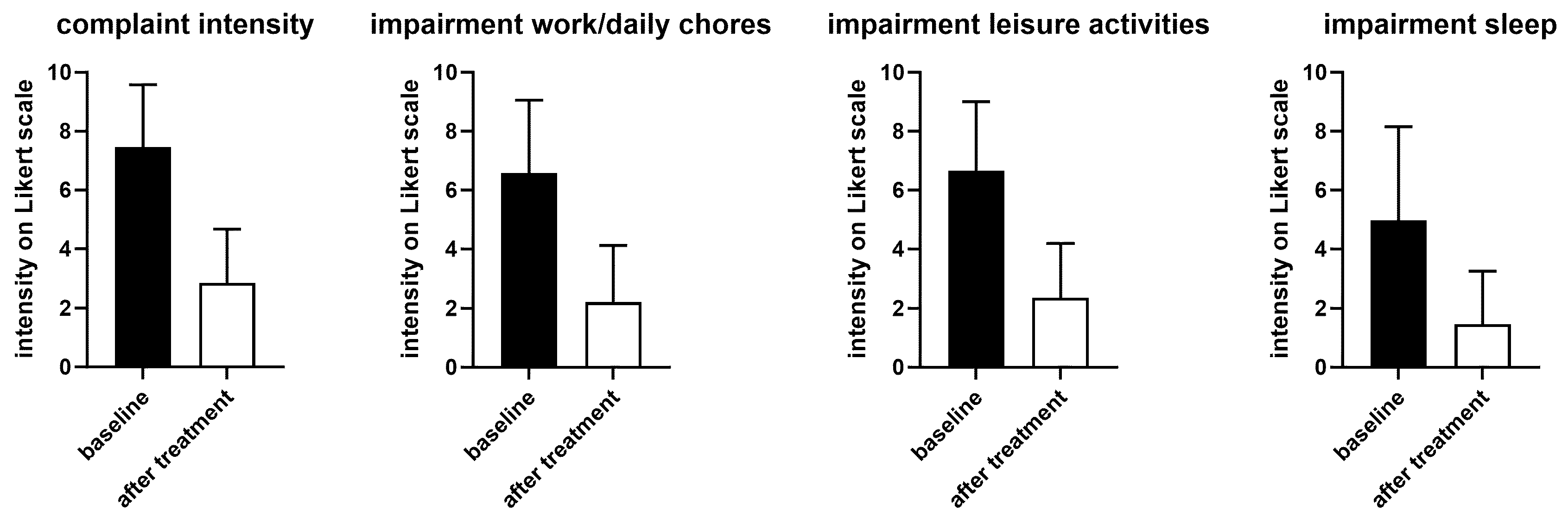

On an 11-point (0-10) Likert scale, the mean and median intensity of overall complaints before treatment were 7.45 ± 2.13 and 8 (IQR 7-9), respectively (

Figure 1). This was associated with impairments of work/daily chores, leisure activity of comparable intensity and, to a somewhat smaller extent, of sleep (

Figure 1).

Participants were asked to identify perceived triggers from a list with multiple possible. Under these conditions, the most frequently reported trigger was “other” (n = 191, 60.8%), most likely reflecting that the menstrual cycle had not been mentioned in the list because the underlying study had a much broader focus (

Table 2). Perceived triggers reported by at least 10% of participants included stress in general, bloating, and nutrition (too fatty or too sweet).

3.2. Treatment Responses

Treatment with PLUS markedly reduced the intensity of complaints and impairment of work/daily chore and leisure activities and of sleep (

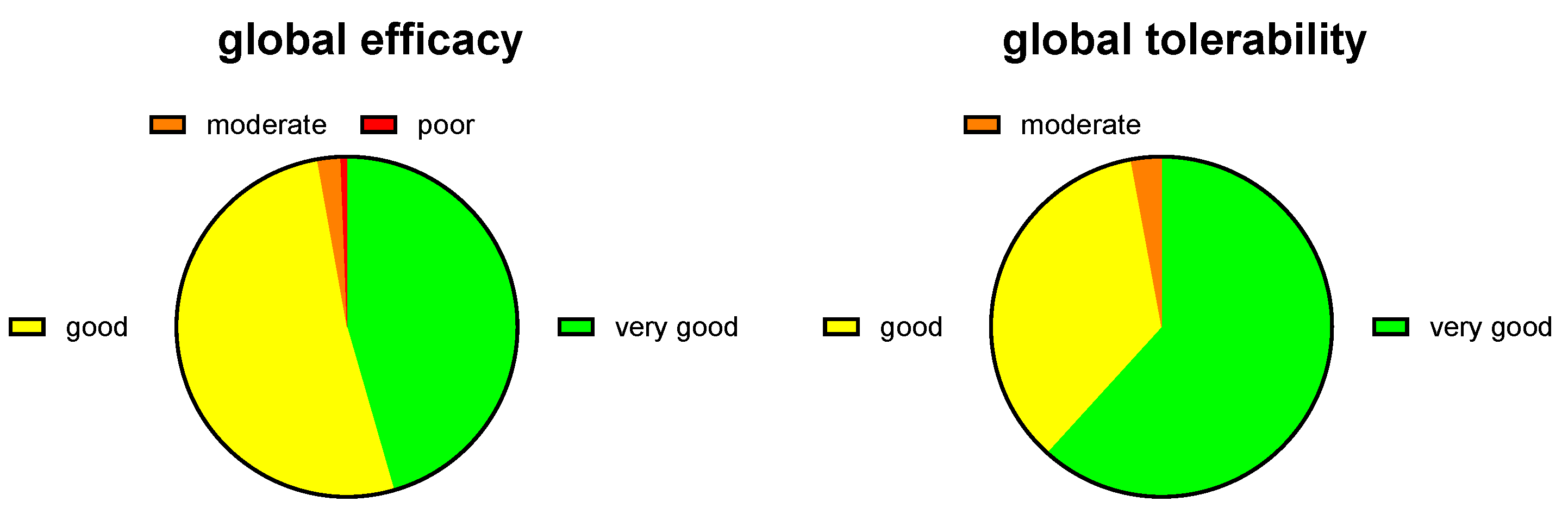

Figure 1). Thus, the intraindividual mean reduction of complaint intensity on the 0-10 Likert scale was 4.55 ± 2.63 (median reduction 5). The improvement of impairment of work/daily chores and leisure activities was >60% and that of sleep about 70%. Accordingly, 45.5% and 51.6% rated the global efficacy of PLUS as very good or good, respectively (

Figure 2). Similarly, 61.8% and 35.4% rated global tolerability as very good or good, respectively (

Figure 2). Of note, none of the participating women rated global tolerability as poor. In line with this experience 97.5% reported their intention to purchase the product again, and 97.1% reported their intention to recommend it to relatives, friends and colleagues.

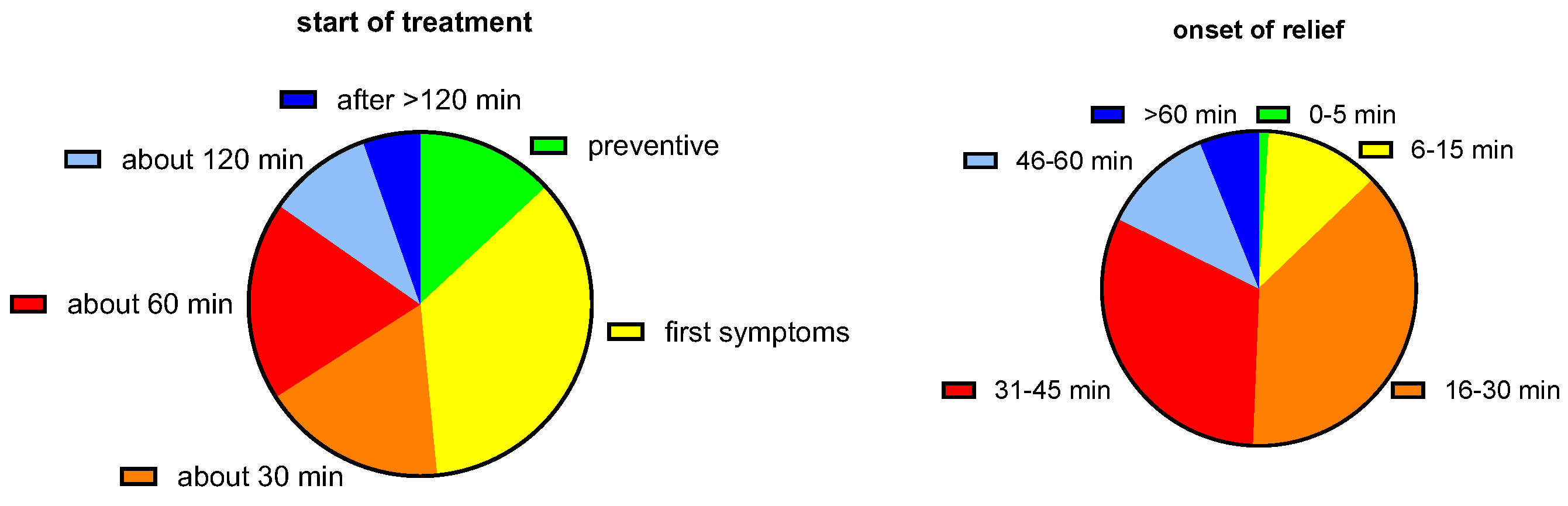

When asked when the first tablet was ingested relative to the onset of symptoms, a mixed picture emerged (

Figure 3). While the largest group (35.4%) reported initiating treatment upon emergence of first symptoms, similarly sized groups started 30 and 60 min after onset, and some even as late as after 2 h; interestingly, some women used PLUS prior to onset of symptoms when they experienced the first signs of having a bad day.

We also asked when the participants experienced the onset of symptom relief after ingestion of the first dose of medication. Half of the participants (50.4%) reported onset of symptom relief after 30 min or earlier and most participants (93.3%) reported after less than 60 min (

Figure 3).

Finally, we wished to learn more about the users of PLUS. The largest fraction obtained PLUS based on a recommendation by a pharmacist (46.2%), followed by recommendations by relatives or friends (34.1%) or by a physician (18.5%); less frequent reasons were advertisements on TV (12.4%), information on the internet (8.0%), and in social media (6.1%); 15.3% did not provide a specific reason. Similar fractions of users had obtained PLUS in a stationary pharmacy (52.5%) and in an online pharmacy (47.5%). Interestingly, 15.3% and 82.8% reported to be first and repeat users, respectively.

4. Discussion

PLUS is an approved medication for the treatment of dysmenorrhea in at least 10 countries. While the effects of HBB and paracetamol against cramps and pain are well documented [

9], the currently available evidence in the public domain underlying its use in dysmenorrhea is limited and rests on three open-label studies [

11,

12,

13] followed by one randomized controlled trial [

14]. Therefore, we have used data from a recently reported PBPS that had included many women using PLUS for the treatment of dysmenorrhea symptoms [

15] to better characterize these women and the perceived treatment benefit.

4.1. Critique of Methods

The present manuscript reports a post-hoc analysis of the subgroup of women reporting using PLUS for the treatment of dysmenorrhea. This subgroup was taken from an overall analysis primarily based on the pooled group of participants irrespective of indication [

15]. The primary study covered three preparations (PLUS, HBB as monotherapy, and peppermint oil) approved for use in multiple indications with abdominal cramps and pain as a shared characteristic. Therefore, it had primarily been designed around gastrointestinal symptoms [

15] and no specific questions about dysmenorrhea were asked. While this is a study limitation, the present data nonetheless provide relevant insight to characterize women using PLUS as a self-medication product to treat dysmenorrhea symptoms and their efficacy and tolerability experience.

The underlying study is a PBPS, which implies specific weaknesses and strengths. Inherently, PBPS and other non-interventional studies are unsuitable to test the effectiveness and safety of a medication relative to an established comparator such as a placebo. Therefore, no claims on absolute efficacy and safety should be derived from PBPS because randomized, controlled trials should address those. Presently, only limited data from controlled trials support the use of PLUS in the treatment of dysmenorrhea [

14] but based on mechanistic plausibility [

10] and the established efficacy and safety of HBB and paracetamol [

9] as components of PLUS, at least 10 countries in Europe, Asia and Latin America have approved the use of PLUS for the treatment of dysmenorrhea. On the other hand, randomized controlled trials also have limitations: They have rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria often resulting in a group of participants that does not match those using the product in real life. Therefore, particularly in OTC products, PBPS have become an established tool to evaluate such products in real-world settings. This includes indications such as functional bowel disorders [

15,

21], headache and migraine [

17,

20,

25] or cough & cold [

18,

19]. These strengths and limitations inherent to PBPS should be considered in interpreting the present data.

In line with recommendations from leading statisticians [

24,

26], the underlying main study had been designed as exploratory and did not address a pre-specified statistical null hypothesis. The post-hoc nature of the present analyses further contributes to an exploratory character. Therefore, no statistical null hypothesis-testing was performed as in the underlying primary study.

4.2. Characterization of Women Using PLUS for the Treatment of Dysmenorrhea Symptoms

Despite the availability of PLUS for the treatment of dysmenorrhea symptoms in at least 10 countries, little is known about the characteristics of users of this product in an OTC environment. Our cohort of 314 women had a mean age of 32.3 years, which is slightly older than that in the randomized controlled trial (26.4 years) [

14]. The latter is also in line with the epidemiological observation that dysmenorrhea is predominantly a condition of younger women [

1]. Prior work had shown that the intensity of pain typically is of moderate to severe extent. For example, a survey among 500 college students found a mean pain intensity of 5.0 on a 10-point visual analog scale [

4] compared to 7.5 on an 11-point Likert scale in our survey. This difference may reflect that women with dysmenorrhea seeking medical treatment are likely to have more severe symptoms than those reporting the presence of the condition in an epidemiological study and not necessarily seeking treatment. An additional possible explanation is that women using an OTC product for the self-management of dysmenorrhea symptoms may be older because this group may have started self-management only after having consulted a physician, i.e., have a more extended disease history. This idea is supported by the observation that 18.5% reported having chosen to use PLUS based upon the recommendation of a physician (and another 46.2% of a pharmacist), implying that they had already consulted a physician about their dysmenorrhea.

While dysmenorrhea mainly manifests as abdominal cramps and pain, it can be accompanied by other symptoms including sleep disturbance; it often leads to impaired quality of life and work productivity [

1,

2,

3]. Our survey data reflects that with a reported degree of impairment of work/daily chores, leisure activities and sleep of 6.6, 6.6, and 5.0 on an 11-point Likert scale (

Figure 1). Other known accompanying symptoms such as constipation and diarrhea were also frequently present in our survey (

Table 2).

Several risk factors for dysmenorrhea have been identified including high stress levels [

1,

2,

3]. The known risk factor stress (25.3%) was the second most often mentioned trigger. As the underlying study was primarily designed to explore abdominal cramps and pain in general, our question on perceived triggers did not include a specific option on menstruation; 61.1% reporting “other” as trigger can be interpreted to reflect menstruation as the primary trigger.

4.3. Outcomes in Women Using PLUS for the Treatment of Dysmenorrhea Symptoms

The only available randomized clinical trial of PLUS in women with dysmenorrhea reported a reduction of pain intensity by 47% (from 2.72 ± 0.6 to 1.45 ± 0.87 on a scale from 0 to 4) [

14]. The decrease in complaint intensity in the present PBPS was 62% (from 7.45 ± 2.13 to 2.86 ± 1.81 on a scale from 0 to 10). While data from a PBPS include a placebo component, data from the randomized trial have shown that the effect of PLUS is greater than with placebo (32%), which also manifests as a greater percentage of women reporting improved symptoms with PLUS than with placebo (82% vs. 63%) [

14]. Importantly, PLUS relative to placebo also reduced concomitant headaches, palpitations, diarrhea, breast pain, and general discomfort in the controlled trial. The present data expands this knowledge by showing that the cramps and pain and the resulting impairments of work/daily chores, leisure activities, and sleep are similarly improved. Accordingly, 97.1% of participants in the PBPS rated global efficiency as very good or good (

Figure 2).

While dysmenorrhea pain abates naturally over several days, the controlled trial had shown that PLUS reduces pain not only on the first day of treatment but also thereafter [

14]. Our data expand this observation by demonstrating that onset of symptom relief occurs within less than an hour in 84.7% of women and in 50.4% even within 30 min (

Figure 3). A rapid onset of symptom relief is important to patients.

The controlled trial found that the incidence of adverse events did not differ between PLUS and placebo [

14]. In line with this observation, 97.2% of women in the present study rated global tolerability as very good or good (

Figure 2).

5. Conclusions

Taken together these data show that women selecting self-management of their dysmenorrhea symptoms by an OTC product such as PLUS are slightly older than those in epidemiological or controlled studies and reported a greater pain intensity compared to epidemiological studies. Despite being older, which implies a longer disease history, the degree of symptom relief in using PLUS in an OTC setting caused symptom relief that was at least as large if not greater than reported in the randomized trial. This together with the excellent safety profile resulted in great patient satisfaction as reflected by 97.5% and 97.1% of patients reporting their intention to use PLUS again and to recommend it to a friend, relative or colleague, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and H.W.; methodology, S.M. and H.W.; formal analysis, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S., S.M., H.W. and R.S.; supervision, H.W. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The underlying study, and medical writing support and the APC for the present manuscript were funded by Sanofi, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Applicable German laws and regulations neither required nor recommended the involvement of an ethical committee for an anonymous survey at the time it was conducted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was implied by the anonymous return of the filled questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

Data are owned by Sanofi (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Qualified researchers may request access to patient level data and related study documents including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan, and dataset specifications. Patient level data will be anonymized and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of our trial participants. Further details on Sanofi's data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at:

https://www.vivli.org/.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Michel Pharma Solutions (Mainz, Germany). We gratefully acknowledge Jia Fu (Winicker-Norimed GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany) for database generation and statistical analyses and Öykü D. Bese (Ankara, Türkiye) for quality assurance services. Moreover, we thank all study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

KS received honoraria from StreamedUp! GmbH. SM and HW are employees of Sanofi, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. RS received honoraria from Astra Zeneca, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Roche Pharma AG, Sanofi-Aventis GmbH and StreamedUp! GmbH.

References

- Ju, H.; Jones, M.; Mishra, G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol. Rev. 2014, 36, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osayande, A.S.; Mehulic, S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 89, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, K.A.; Fogleman, C.D. Dysmenorrhea. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grandi, G.; Ferrari, S.; Xholli, A.; Cannoletta, M.; Palma, F.; Romani, C.; Volpe, A.; Cagnacci, A. Prevalence of menstrual pain in young women: what is dysmenorrhea? J. Pain Res. 2012, 5, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, R.; Anić, K.; Stewen, K.; Schmidt, M.W.; Kalb, S.R.; Kottmann, T.; Brenner, W.; Domidian, J.S.; Krajnak, S.; Battista, M.J.; Hasenburg, A. Pain experience and social support of endometriosis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany - results of a web-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0256433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, R.; Stewen, K.; Kottmann, T.; Anic, K.; Schmidt, M.W.; Elger, T.; Theis, S.; Kalb, S.R.; Brenner, W.; Hasenburg, A. Mental health and social support are key predictors of resilience in German women with endometriosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Bhandari, M.S.; Shrestha, S.S.; Shrestha, J.T.M.; Shrestha, U. Self-medication in Primary Dysmenorrhea among Undergraduate Students in a Medical College: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2022, 60, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, R.; Stewen, K.; Kottmann, T.; Schmidt, M.W.; Anic, K.; Theis, S.; Hamoud, B.H.; Elger, T.; Brenner, W.; Hasenburg, A. Factors Associated with Increased Analgesic Use in German Women with Endometriosis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tytgat, G.N. Hyoscine butylbromide: a review of its use in the treatment of abdominal cramping and pain. Drugs 2007, 67, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesuíno, F.; Reis, J.P.; Whitaker, J.C.P.; Campos, A.; Pastor, M.V.D.; Cechinel Filho, V.; Quintão, N.L.M. Effect of Synadenium grantii and its isolated compound on dysmenorrhea behavior model in mice. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picallo, R. [Treatment of dysmenorrhea with buscopan compositum]. Rev. Esp. Obstet. Ginecol. 1958, 17, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Odeblad, E. The therapeutic efficacy of Buscopan in primary dysmenorrhea. Z.Ther. 1975, 13, 473–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Bueno, J.A.; de la Jara Díaz, J.; Sedeño Cruz, F.; Llorens Torres, F. [Analgesic-antispasmodic effect and safety of lysine clonixinate and L-hyoscinbutylbromide in the treatment of dysmenorrhea]. Ginecol. Obstet. Mex. 1998, 66, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- de los Santos, A.R.; Zmijanovich, R.; Pérez Macri, S.; Martí, M.L.; Di Girolamo, G. Antispasmodic/analgesic associations in primary dysmenorrhea double-blind crossover placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 2001, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Storr, M.; Weigmann, H.; Landes, S.; Michel, M.C. Self-medication for the treatment of abdominal cramps and pain - a real-life comparison of three frequently used preparations. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.R.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Lumsden, M.; Mishra, G.D.; Pal, L.; Rees, M.; Santoro, N.; Simoncini, T. Menopause. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, C.; Gräter, H.; Weiser, T. Results from a pharmacy-based patient survey on the use of a fixed combination analgesic containing acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol and caffeine by self-diagnosing and self-treating patients. Springerplus 2016, 5, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, L.; Schumacher, H.; Schütt, T.; Gräter, H.; Mück, T.; Michel, M.C. Factors associated with efficacy of an ibuprofen/pseudoephedrine combination drug in pharmacy customers with common cold symptoms. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 71, e12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, P.; Beeh, K.-M.; Sent, U.; Mueck, T.; Gräter, H.; Michel, M.C. Characterization of differential patient profiles and therapeutic responses of pharmacy customers for four ambroxol formulations. BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology 2018, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, C.; Gräter, H.; Weiser, T.; Michel, M.C.; Lampert, A.; Plomer, M.; Förderreuther, S. Impact of the neck and/or shoulder pain on self-reported headache treatment responses – results from a pharmacy-based patient survey. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 902020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Lissner, S.; Schäfer, E.; Kondla, A. Symptoms and their interpretation in patients self-treating abdominal cramping and pain with a spasmolytic (butylscoplolamine bromide) - a pharmacy-based survey. Pharmacology & Pharmacy 2011, 2, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollert, J.; Schenker, E.; Macleod, M.; Bespalov, A.; Wuerbel, H.; Michel, M.; Dirnagl, U.; Potschka, H.; Waldron, A.-M.; Wever, K.; et al. Systematic review of guidelines for internal validity in the design, conduct and analysis of preclinical biomedical experiments involving laboratory animals. BMJ Open Science 2020, 4, e100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.C.; Murphy, T.J.; Motulsky, H.J. New author guidelines for displaying data and reporting data analysis and statistical methods in experimental biology. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2020, 48, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrhein, V.; Greenland, S.; McShane, B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature 2019, 567, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, H.; Gessner, U.; Petersen-Braun, M.; Weingärtner, U. Acetylsalicylic acid in self-medication of migraine. A pharmacy-based observational study. Schmerz 2007, 21, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, M.C.; Murphy, T.J.; Motulsky, H.J. New author guidelines for displaying data and reporting data analysis and statistical methods in experimental biology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 372, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).