Submitted:

20 February 2024

Posted:

22 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

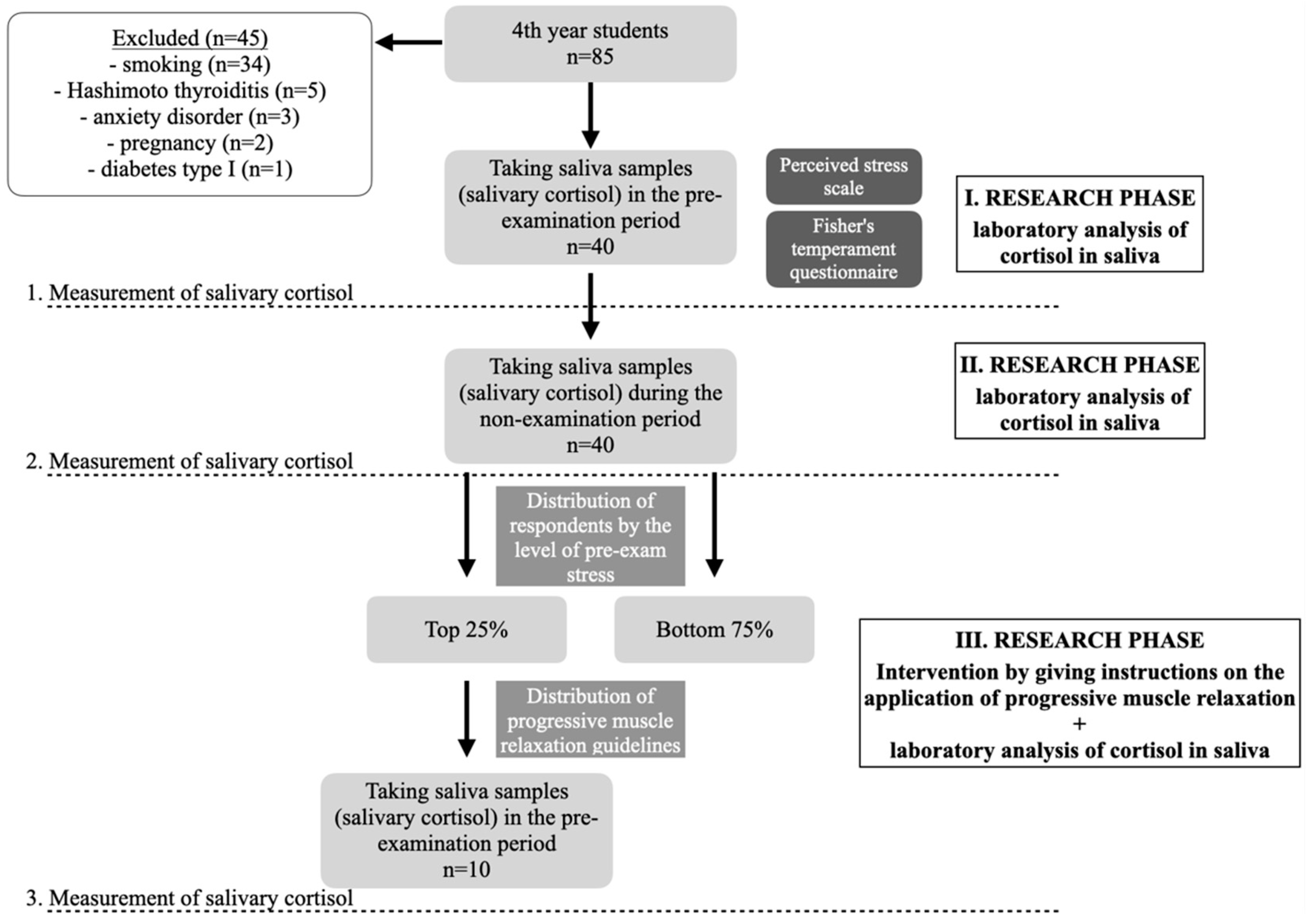

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Respondents

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Saliva Collection Method and Salivary Cortisol Analysis

2.2.2. Measuring Stress Using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and Determining Temperament Using the Fisher Temperament Inventory (FTI)

2.2.3. Evaluation of Questionnaires, Follow-Up Procedure and Other Cortisol Measurement

2.2.4. Third Cortisol Measurement Following Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) - and Its Use in Subjects with a Third Cortisol Measurement

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

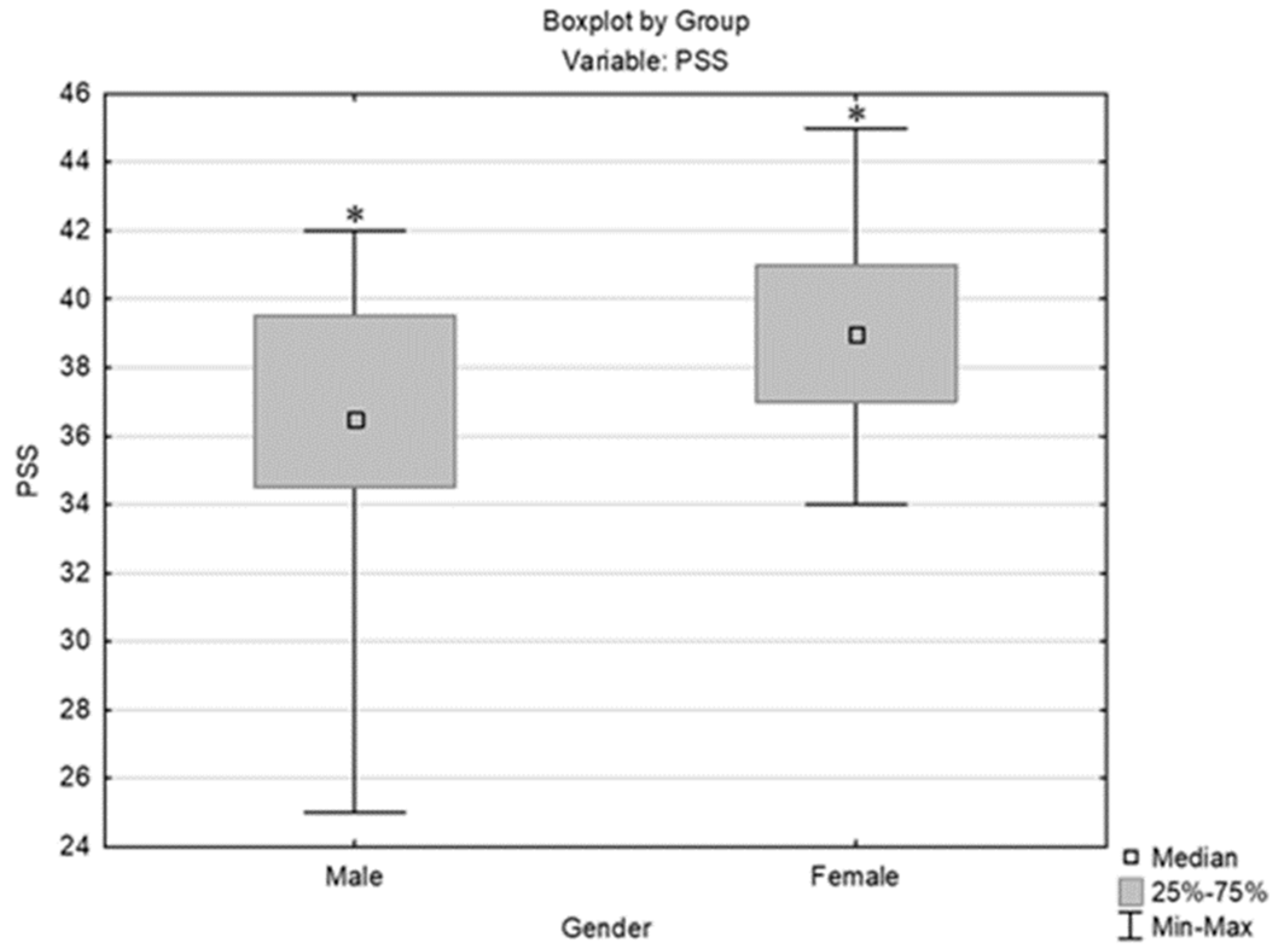

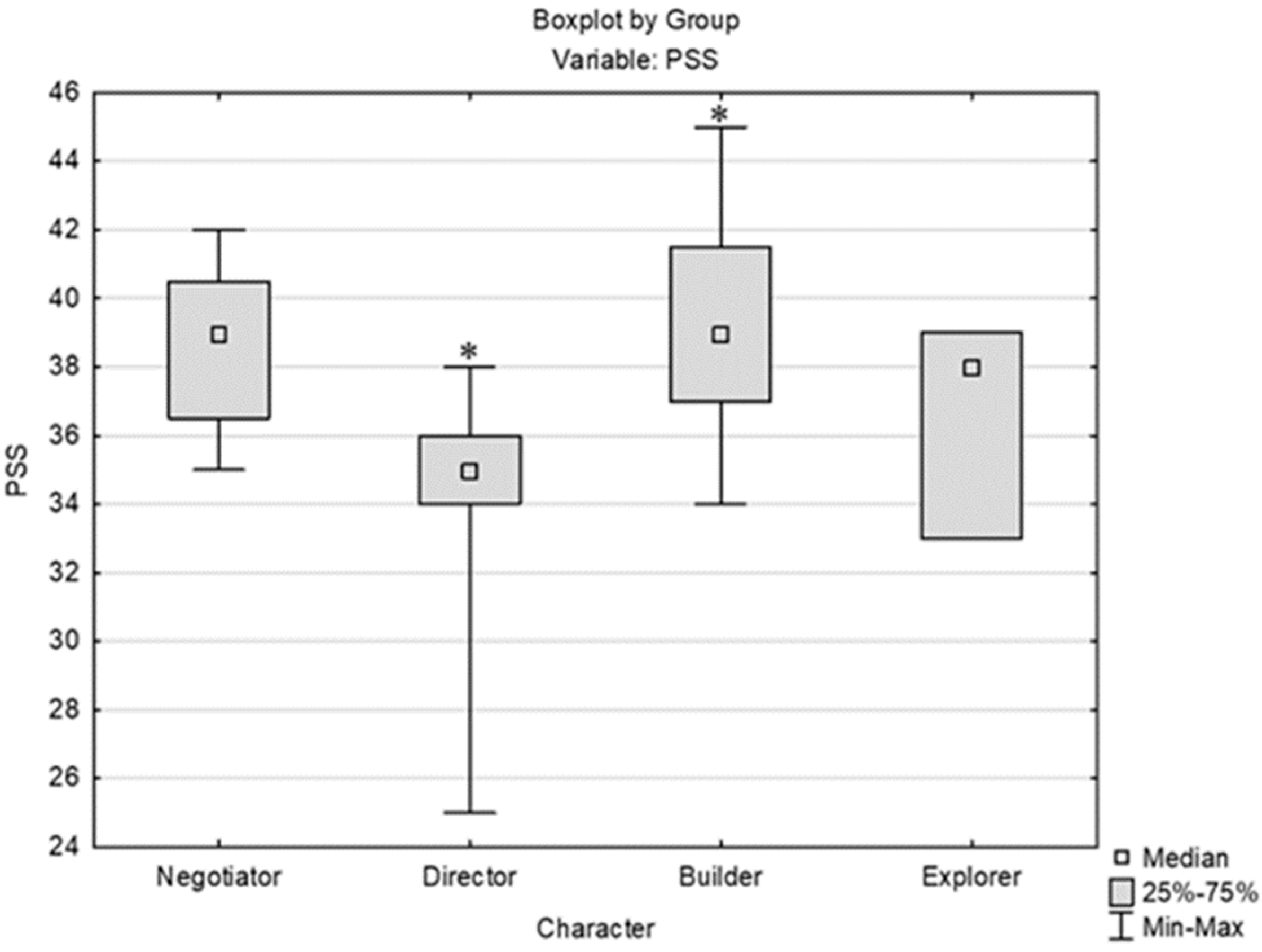

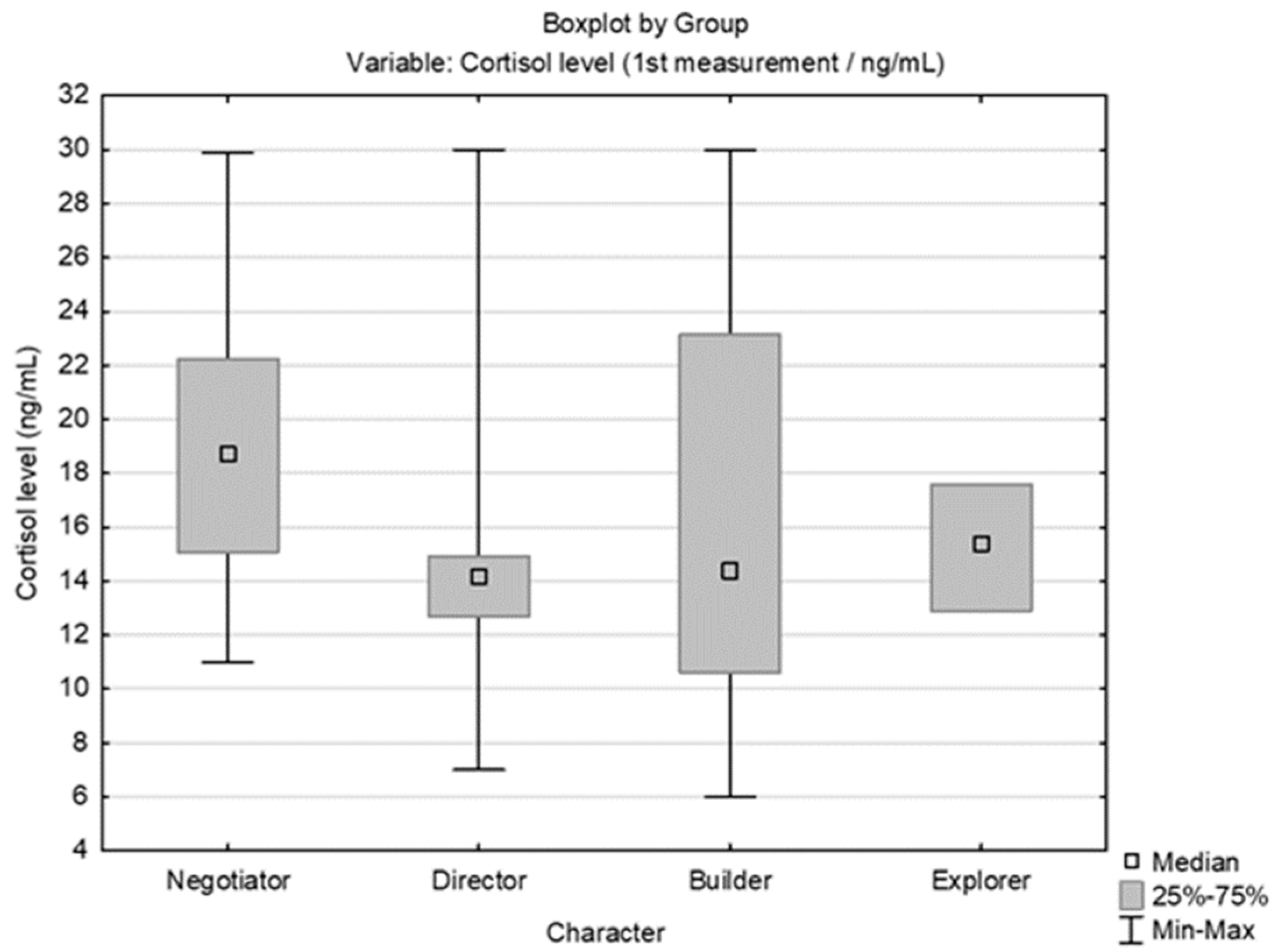

3.1. Analysis of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Results in Relation to Other Parameters/Variables

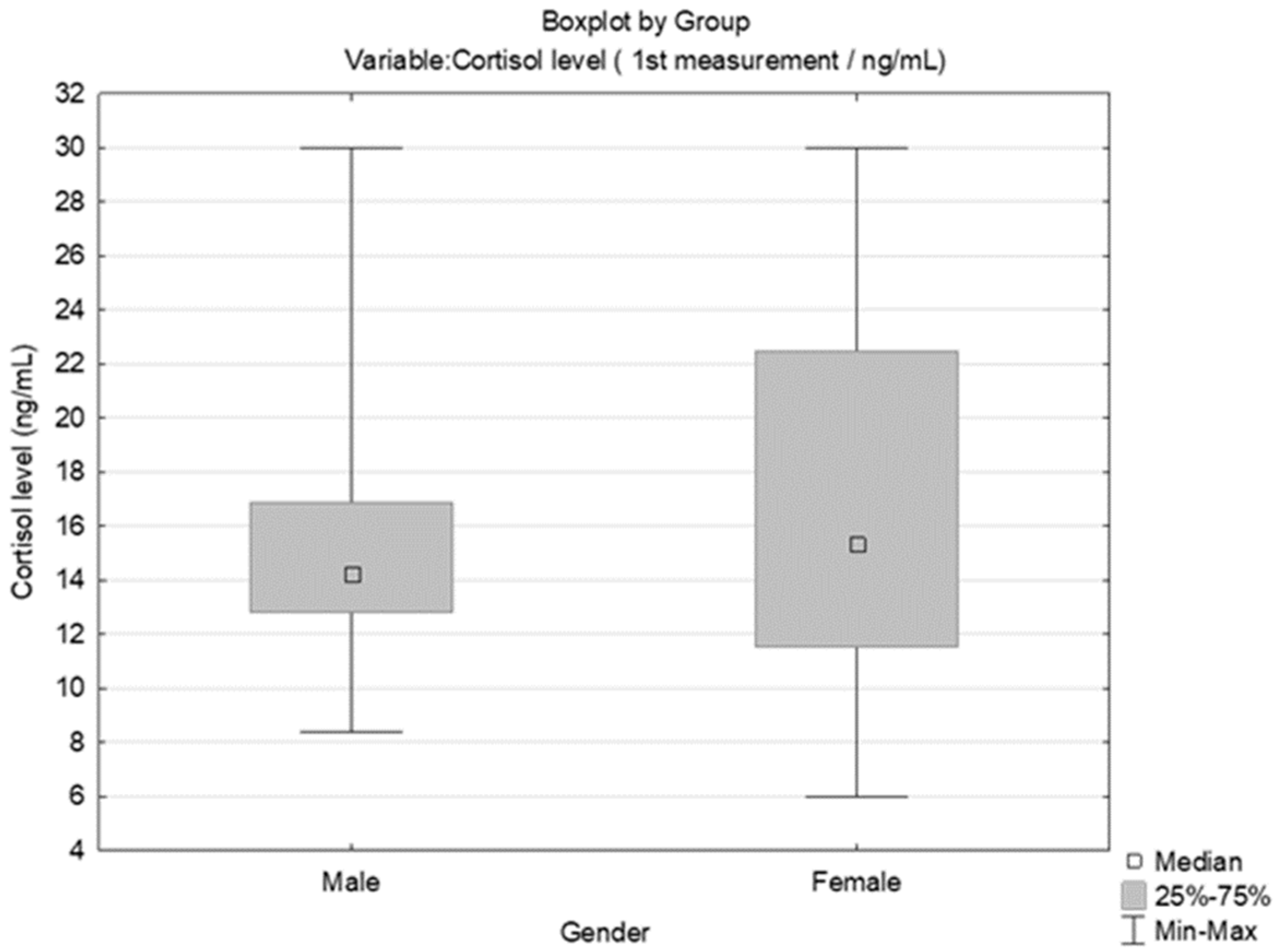

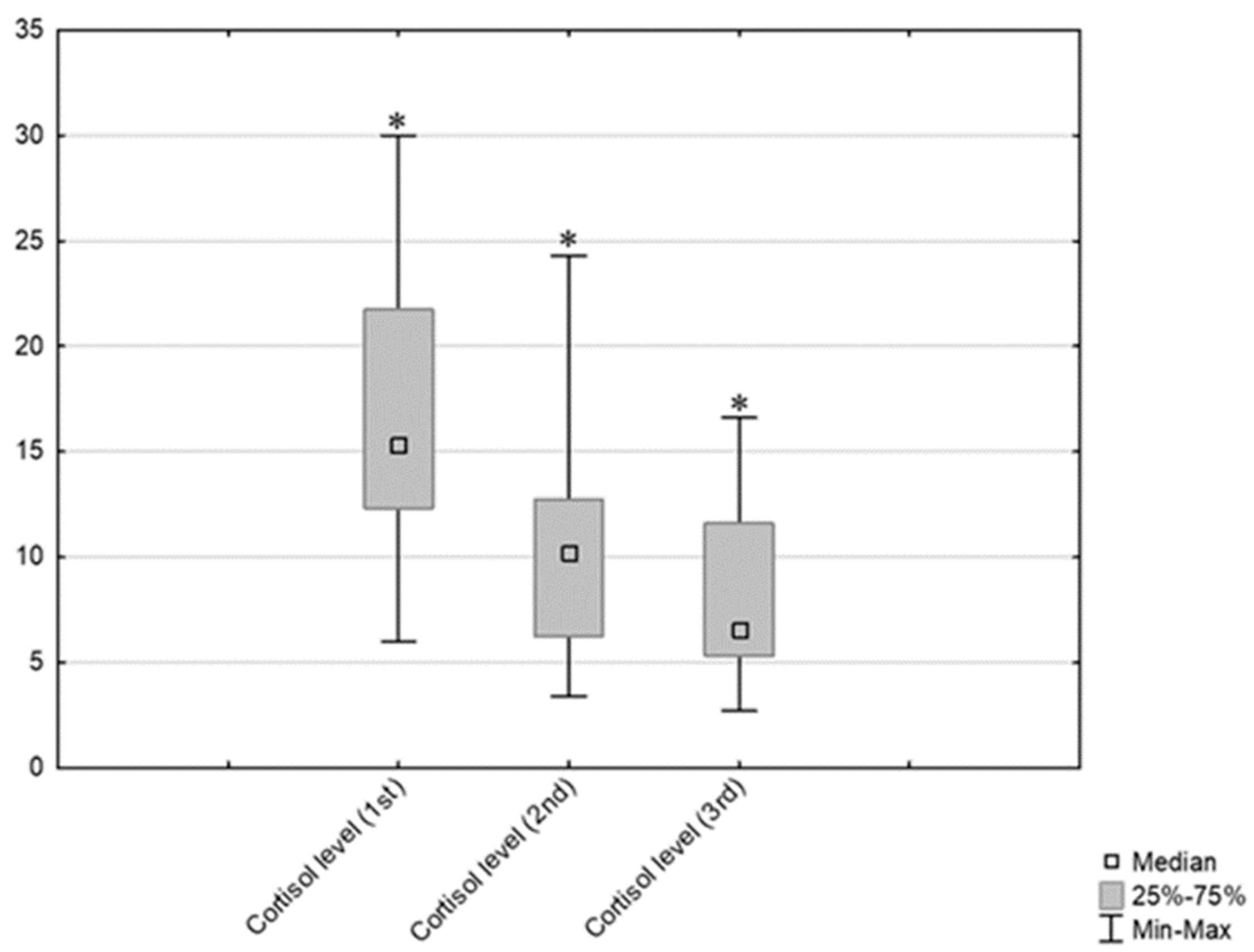

3.2. Results Obtained by Salivary Cortisol Analysis

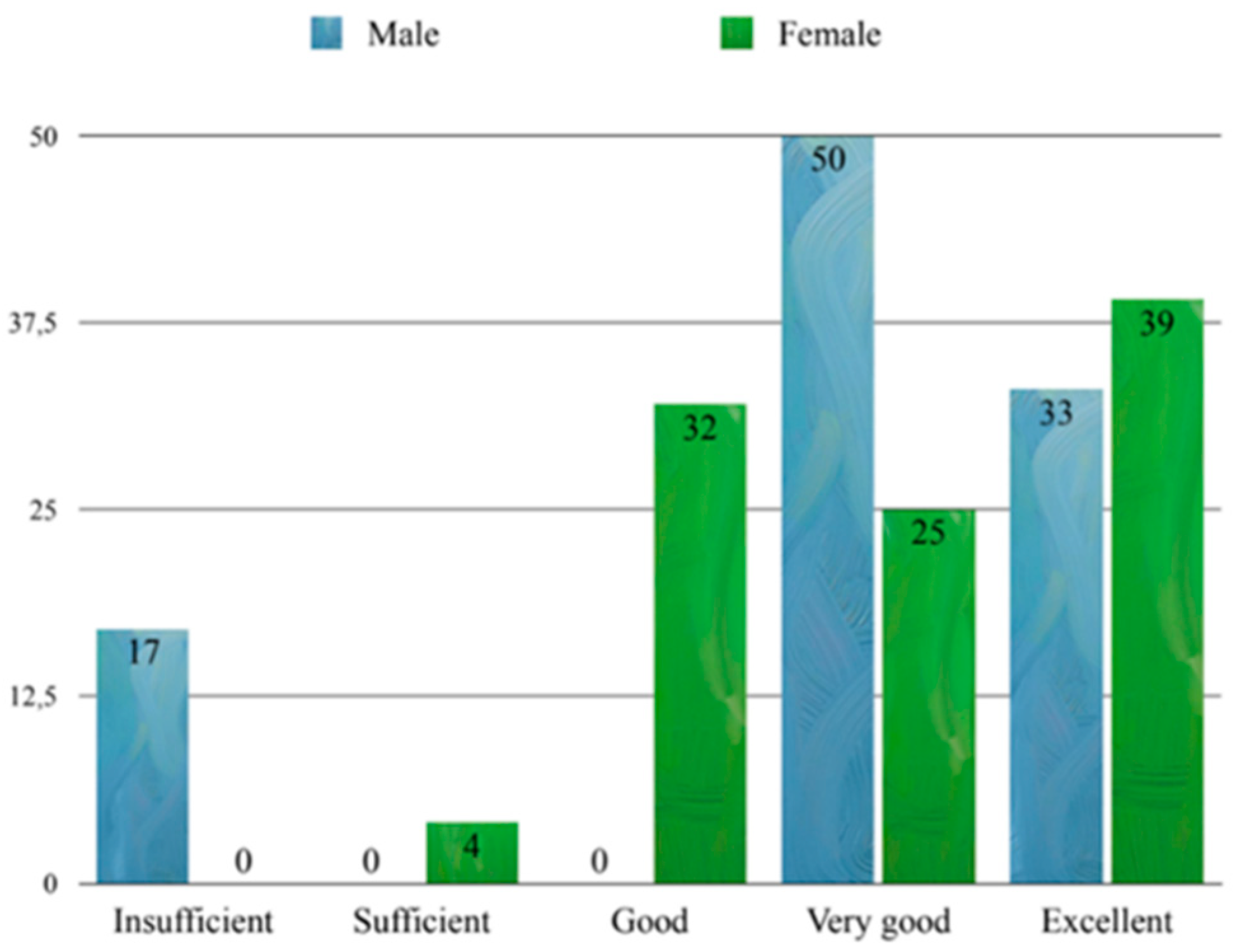

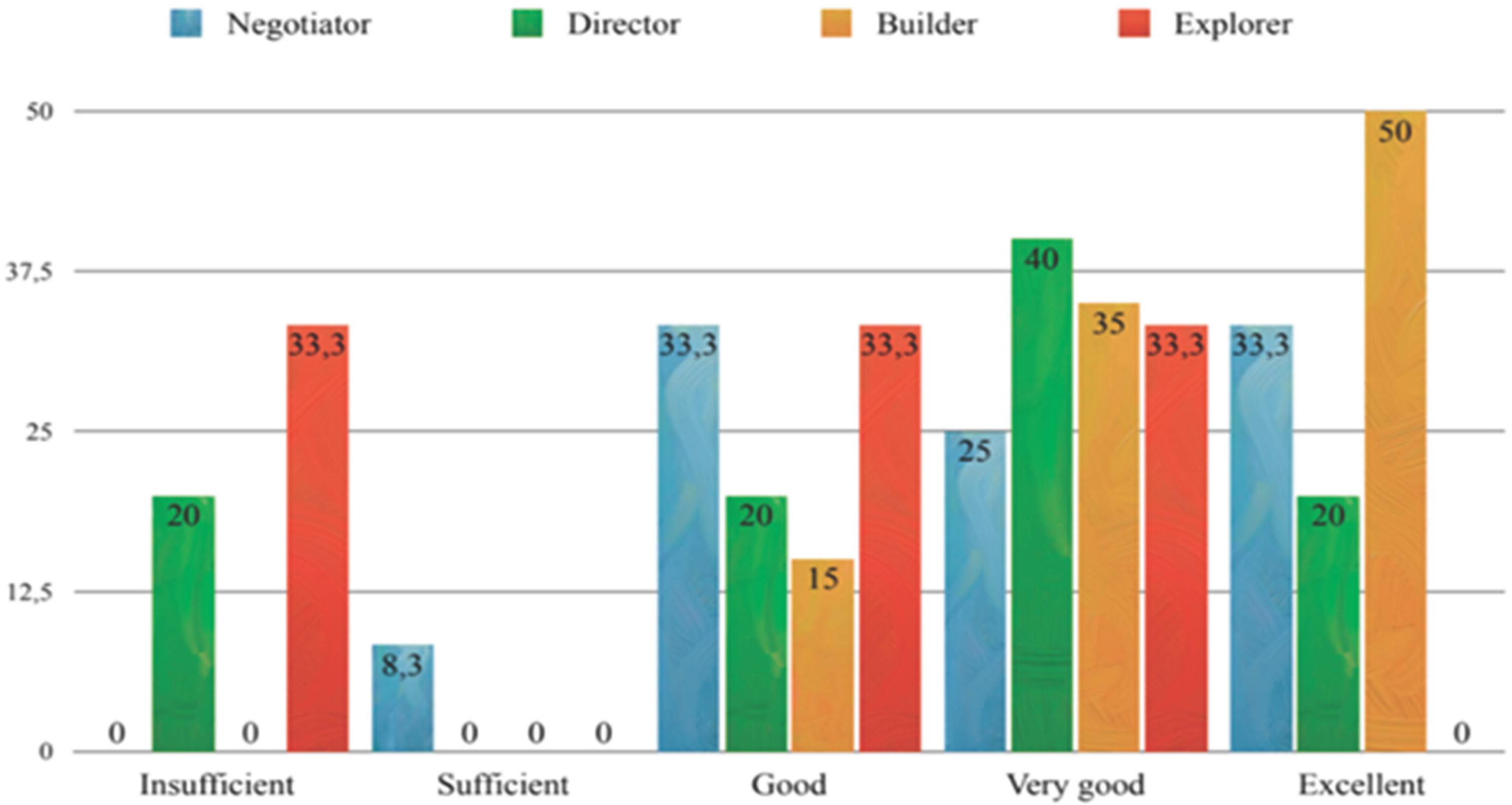

3.3. Exam Scores and Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knowles, S. R.; Nelson, E. A.; Palombo, E. A. Investigating the Role of Perceived Stress on Bacterial Flora Activity and Salivary Cortisol Secretion: A Possible Mechanism Underlying Susceptibility to Illness. Biol. Psychol. 2008, 77, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemmott, J. B., III; Magloire, K. Academic Stress, Social Support, and Secretory Immunoglobulin A. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Doniec, R.; Trzcionka, A.; Pachoński, M.; Piaseczna, N.; Sieciński, S.; Osadcha, O.; Łanowy, P.; Tanasiewicz, M. Evaluating the Stress-Response of Dental Students to the Dental School Environment. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, J. P. M.; Seixas, G. F.; Ramos, S. de Paula; Dezan-Garbelini, C. C. Salivary Levels of SIgA and Perceived Stress Among Dental Students. J. Health Biol. Sci. 2018, 6, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolova, M. S.; Stefanova, V. P.; Manchorova-Veleva, N. A.; Panayotov, I. V.; Levallois, B. , et al. A Five-Year Comparative Study of Perceived Stress Among Dental Students at Two European Faculties. Folia Med. (Plovdiv) 2019, 61, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouda, S.; Sumer, A.; Safi, M.-A.; Nadhreen, A.; Al-Johani, K. Salivary Stress Biomarkers- Are They Predictors of Academic Assessment Exams Stress? J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2016, 15, 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Pani, S. C.; Al Askar, A. M.; Al Mohrij, S. I.; Al Ohali, T. A. Evaluation of Stress in Final-Year Saudi Dental Students Using Salivary Cortisol as a Biomarker. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama, K.; Latheef, S. K.; Dadar, M.; Samad, H. A.; Munjal, A.; Khandia, R. , et al. Biomarkers in Stress Related Diseases/Disorders: Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Values. Front Mol Biosci. 2019, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, R.; Matsuda, A.; Nomura, I.; Matsubara, O.; Nonoyama, S.; Ohya, Y. , et al. Salivary Cortisol Response to Stress in Young Children with Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 30, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, A.; Singh, S.; Vir, D.; Pershad, D. Automation of Stress Recognition Using Subjective or Objective Measures. Psychol. Stud. 2016, 61, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSarhan, M. A.; AlJasser, R. N.; AlOraini, S.; Habib, S. R.; Alayoub, R. A.; Almutib, L. T.; Aldokhi, H. D.; AlKhalaf, H. H. Evaluation and Comparison of Cortisol Levels in Saliva and Hair Among Dental Students. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellhammer, D. H.; Wust, S.; Kudielka, M. B. Salivary Cortisol as a Biomarker in Stress Research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Hanžek, M.; Bešlić, I.; Japundžić, I.; Karlović, D. Salivary Cortisol Values and Personality Features of Atopic Dermatitis Patients: A Prospective Study. Dermatitis. [CrossRef]

- Inder, W. J.; Dimeski, G.; Russel, A. Measurement of Salivary Cortisol in 2012-Laboratory Techniques and Clinical Investigations. Clin. Endocrinol. 2012, 77, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruessner, J. C.; Wolf, O. T.; Hellhammer, D. H.; Buske-Kirschbaum, A.; von Auer, K.; Jobst, S. , et al. Free Cortisol Levels After Awakening: A Reliable Biological Marker for the Assessment of Adrenocortical Activity. Life Sci. 1997, 61, 2539–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudielka, B. M.; Hellhammer, D. H.; Wurs, S. Why Do We Respond So Differently? Reviewing Determinants of Human Salivary Cortisol Responses to Challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, G.; Ahs, A.; Lundberg, U. Psychological Correlates of Salivary Cortisol Secretion Among Unemployed Men and Women. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 1998, 33, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, N. C.; Kudielka, B. M.; Hellhammer, D. H.; Kirschbaum, C. No Evidence for a Close Relationship Between Personality Traits and Circadian Cortisol Rhythm or a Single Cortisol Stress Response. Psychol. Rep. 1999, 84, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Mason, J.; Charney, D.; Yehuda, R.; Riney, S.; Southwick, S. Relationships Between Hormonal Profile and Novelty Seeking in Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 1997, 41, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navazesh, M.; Kumar, S. K. Measuring Salivary Flow: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 35S–40S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špiljak, B.; Vilibić, M.; Glavina, A.; Crnković, M.; Šešerko, A.; Lugović-Mihić, L. A Review of Psychological Stress Among Students and Its Assessment Using Salivary Biomarkers. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, M. Salivary Cortisol Profile Under Different Stressful Situations in Female College Students: Moderating Role of Anxiety and Sleep. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2018, 50, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoofs, D.; Hartmann, R.; Wolf, O. T. Neuroendocrine Stress Responses to an Oral Academic Examination: No Strong Influence of Sex, Repeated Participation and Personality Traits. Stress 2008, 11, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringeisen, T.; Lichtenfeld, S.; Becker, S.; Minkley, N. Stress Experience and Performance During an Oral Exam: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Threat Appraisals, Anxiety, and Cortisol. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancheri, P.; Biondi, M. In: Leonard, B. E.; Miller, K., Eds. Stress, The Immune System and Psychiatry. Wiley: New York, 1994; pp. 86–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cortisol Saliva Test Instruction. (written on the attached paper prepared for ELISA for salivary cortisol measurement, supplied by the manufacturer).

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, H. E.; Island, H. D.; Rich, J.; Marchalik, D.; Brown, L. L. Four Broad Temperament Dimensions: Description, Convergent Validation Correlations, and Comparison with the Big Five. Front Psychol. 2015, 6, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottaccioli, A. G.; Bottaccioli, F.; Carosella, A.; Cofini, V.; Muzi, P.; Bologna, M. Psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology-Based Meditation (PNEIMED) Training Reduces Salivary Cortisol Under Basal and Stressful Conditions in Healthy University Students: Results of a Randomized Controlled Study. Explore (NY) 2020, 16, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschel, T. L.; Young, J. C.; Navalta, J. W. Examining the Impact of a University-Driven Exercise Programming Event on End-of-Semester Stress in Students. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017, 10, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mackereth, P. A.; Tomlinson, L. Progressive Muscle Relaxation: A Remarkable Tool for Therapists and Patients, Integrative Hypnotherapy. In Cawthorn, A.; Mackereth, P. A., Eds. Integrative Hypnotherapy. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2010; pp. 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zargarzadeh, M.; Shirazi, M. The Effect of Progressive Muscle Relaxation Method on Test Anxiety in Nursing Students. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 2014, 19, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, L.; Nguyen, Q. A.; Roettger, C.; Dixon, K.; Offenbächer, M.; Kohls, N. , et al. Effectiveness of Progressive Muscle Relaxation, Deep Breathing, and Guided Imagery in Promoting Psychological and Physiological States of Relaxation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021, 2021, 5924040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, G.; Urquhart, J.; Greenman, J. Academic Stress and Secretory Immunoglobulin A. Psychol Rep. 2000, 87, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, K.; Zaharia, M. D.; Griffiths, J.; Ravindran, A. V.; Merali, Z.; Anisman, H. A Prospective Study of Neuroendocrine and Immune Alterations Associated with the Stress of an Oral Academic Examination Among Graduate Students. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000, 25, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, J. R.; MacFarlane, T. V.; Umar, M. S. Perceived Sources of Stress in Dental Students. Dent Update. 1999, 26, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, A. E.; Lushington, K. Sources of Stress for Australian Dental Students. J. Dent. Educ. 1999, 63, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, P. P. N. S.; de Souza Ferreira, F.; Pazos, J. M. Stress Among Dental Students Transitioning from Remote Learning to Clinical Training During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 86, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Dagli, R. J.; Mathur, A.; Jain, M.; Prabu, D.; Kulkarni, S. Perceived Sources of Stress Amongst Indian Dental Students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2009, 13, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, Z.; Dravo, U. Stress Levels of Dental Students at the Fiji School of Medicine. Eur J Dent Educ. 2007, 11, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muirhead, V.; Locker, D. Canadian Dental Students’ Perceptions of Stress. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Polychronopoulou, A.; Divaris, K. A Longitudinal Study of Greek Dental Students’ Perceived Sources of Stress. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 74, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosli, T. I.; Abdul Rahman, R.; Abdul Rahman, S. R.; Ramli, R. A Survey of Perceived Stress Among Undergraduate Dental Students in Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Singapore Dent J. 2005, 27, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann, K.; Jonas, I.; Ruf, S.; Harzer, W. Stress, Burnout and Health in the Clinical Period of Dental Education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 9, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G. H.; Grandy, T. G.; Ocanto, R. A.; Erskine, C. G. Perceived Sources of Stress in the Dental School Environment. J. Dent. Educ. 1993, 57, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenhaeuser, M.; von Wright, M. R.; Collins, A.; von Wright, J.; Sedvall, G.; Swahn, C. G. Sex Differences in Psychoneuroendocrine Reactions to Examination Stress. Psychosom. Med. 1978, 40, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Kudielka, B. M.; Gaab, J.; Schommer, N. C.; Hellhammer, D. H. Impact of Gender, Menstrual Cycle Phase, and Oral Contraceptives on the Activity of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Psychosom. Med. 1999, 61, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter-Snell, C.; Hegadoren, K. Stress Disorders and Gender: Implications for Theory and Research. CJNR (Canadian Journal of Nursing Research) 2003, 35, 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gater, R.; Tansella, M.; Korten, A.; Tiemens, B. G.; Mavreas, V. G.; Olatawura, M. O. Sex Differences in the Prevalence and Detection of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in General Health Care Settings: Report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998, 55, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, P.; Yang, A.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ren, X.; Dai, Q. A Hypothesis of Gender Differences in Self-Reporting Symptom of Depression: Implications to Solve Under-Diagnosis and Under-Treatment of Depression in Males. Front Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 589687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M. M.; Tyrka, A. R.; Anderson, G. M.; Price, L. H.; Carpenter, L. L. Sex Differences in Emotional and Physiological Responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2008, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M. M.; Forsyth, J. P.; Karekla, M. Sex Differences in Response to a Panicogenic Challenge Procedure: An Experimental Evaluation of Panic Vulnerability in a Non-Clinical Sample. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, B. S.; Hall, M. E.; Dias-Karch, C.; Haischer, M. H.; Apter, C. Gender Differences in Perceived Stress and Coping Among College Students. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaksari, M.; Mahmoodi, M.; Rezvani, M. E.; Sajjadi, M. A.; Karam, G. A.; Hajizadeh, S. Differences Between Male and Female Students in Cardiovascular and Endocrine Responses to Examination Stress. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2005, 17, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Goyal, M.; Tiwari, S.; Ghildiyal, A.; Nattu, S. M.; Das, S. Effect of Examination Stress on Mood, Performance and Cortisol Levels in Medical Students. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 56, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinek, L.; Oberascher-Holzinger, K.; Weishuhn, S.; Klimesch, W.; Kerschbaum, H. H. Anticipated Academic Examinations Induce Distinct Cortisol Responses in Adolescent Pupils. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2003, 24, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Batabyal, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Thaker, M.; Mukherjee, S. A Longitudinal Study of Perceived Stress and Cortisol Responses in an Undergraduate Student Population from India. PLoS One. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschoor, E.; Markus, C. R. Affective and Neuroendocrine Stress Reactivity to an Academic Examination: Influence of the 5-HTTLPR Genotype and Trait Neuroticism. Biological Psychology. 2011, 87, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, R.; Pearl, D. K.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K.; Malarkey, W. B. Plasma Cortisol Levels and Reactivation of Latent Epstein-Barr Virus in Response to Examination Stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1994, 19, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedhara, K.; Hyde, J.; Gilchrist, I. D.; Tytherleigh, M.; Plummer, S. Acute Stress, Memory, Attention and Cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000, 25, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuss, D.; Schoofs, D.; Schlotz, W.; Wolf, O. T. The Stressed Student: Influence of Written Examinations and Oral Presentations on Salivary Cortisol Concentrations in University Students. Stress. 2010, 13, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerfald, K.; Eberle, C.; Grau, M.; Kinsperger, A.; Zimmermann, A.; Ehlert, U. , et al. Persistent Effects of Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management on Cortisol Responses to Acute Stress in Healthy Subjects--A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denson, T. F.; Spanovic, M.; Miller, N. Cognitive Appraisals and Emotions Predict Cortisol and Immune Responses: A Meta-Analysis of Acute Laboratory Social Stressors and Emotion Inductions. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 823–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackschewitz, H.; Hüther, G.; Kröner-Herwig, B. Physiological and Psychological Stress Responses in Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2008, 33, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldehinkel, A. J.; Ormel, J.; Bosch, N. M.; Bouma, E. M.; Van Roon, A. M.; Rosmalen, J. G.; Riese, H. Stressed Out? Associations Between Perceived and Physiological Stress Responses in Adolescents: The TRAILS Study. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlotz, W.; Kumsta, R.; Layes, I.; Entringer, S.; Jones, A.; Wüst, S. Covariance Between Psychological and Endocrine Responses to Pharmacological Challenge and Psychosocial Stress: A Question of Timing. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, H. E.; Rich, J.; Island, H. D.; Marchalick, D.; Silver, L. Do We Have Chemistry? Four Primary Temperament Dimensions on Mate Choice. [Conference presentation]. APA 2010, San Diego, United States.

- Lucić, A.; Šimić, N. Testing the Fisher’s Temperament Model on a Croatian Sample. In: A. Tokić (Ed.), 21st Psychology Days in Zadar – Book of Selected Proceedings, pp. 97–108. Zadar: University in Zadar.

- Pruessner, J. C.; Gaab, J.; Hellhammer, D. H.; Lintz, D.; Schommer, N.; Kirschbaum, C. Increasing Correlations Between Personality Traits and Cortisol Stress Responses Obtained by Data Aggregation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1997, 22, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, L. M.; Zandi, P.; Nestadt, G.; Potash, J. B.; Kalaydjian, A. E.; Wand, G. S. Relationship Between Cortisol Responses to Stress and Personality. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pv, J.; Lobo, S. M. Effectiveness of Relaxation Technique in Reducing Stress Among Nursing Students. International Journal of Nursing and Health Research 2020, 2, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arabaci, L. B.; Korhan, E. A.; Tokem, Y.; Torun, R. Pre-clinical and Postclinical Anxiety and Stress Levels of First-Year Nursing Students and Factors Affecting Them. Ankara, Turkey: Hacettepe University Nursing Faculty Journal; 2015:1-16.

- Dehkordi, A. H.; Masoudi, R.; Tali, S. S.; Frouzandeh, N.; Naderipour, A.; Pourmirzakalhori, R. , et al. The Effect of Progressive Muscle Relaxation on Anxiety and Stress in Nursing Students at the Beginning of the Internship Program. Journal of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences 2009, 11, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Manansingh, S.; Tatum, S. L.; Morote, E. S. Effects of Relaxation Techniques on Nursing Students’ Academic Stress and Test Anxiety. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagec, T.; Glavina, A.; Špiljak, B.; Bešlić, I.; Bulat, V.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Cheilitis: A Cross-Sectional Study-Multiple Factors Involved in the Aetiology and Clinical Features. Oral Dis. 3360. [Google Scholar]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Špiljak, B.; Blagec, T.; Delaš Aždajić, M.; Franceschi, N.; Gašić, A.; Parać, E. Factors Participating in the Occurrence of Inflammation of the Lips (Cheilitis) and Perioral Skin. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parać, E.; Špiljak, B.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Bukvić Mokos, Z. Acne-like Eruptions: Disease Features and Differential Diagnosis. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japundžić, I.; Bembić, M.; Špiljak, B.; Parać, E.; Macan, J.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Work-Related Hand Eczema in Healthcare Workers: Etiopathogenic Factors, Clinical Features, and Skin Care. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).