Introduction

Gastric syphilis is a sexually transmitted entity with a rising incidence (1). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is an estimated cumulative incidence of 7 million cases annually in adults aged 15-49, with a higher prevalence in men engaged in homosexual relationships.

Syphilis infection is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, manifesting in three distinct stages over time. Initially, it involves the development of an ulcerated lesion in the affected area, followed by systemic involvement, and eventually, a final phase characterized by organic damage, typically occurring many years after the primary infection. Gastric involvement is rare, accounting for only 1% of presentations, predominantly in the secondary stage (3,5).

In this article, we explore the case of a patient with gastric syphilis initially thought to be malignant. The objective is to shed light on the diagnostic challenges posed by this rare manifestation, especially when mimicking tumors. The increasing incidence of syphilis and its potential to imitate malignancy highlight the necessity for heightened awareness among clinicians and healthcare providers.

Case Description

We present the case of a 35-year-old male chef with a previous history of hypertension and obesity. He was admitted to our hospital’s Emergency Department for evaluation after experiencing two episodes of hematemesis of approximately 200 and 300 ml each within the past 24 hours. The patient reported a 3-week history of moderate to severe, continuous, and oppressive epigastric pain that worsened towards the end of the day, unresponsive to acetaminophen. The pain was unaffected by dietary intake, position, defecation, or passing gas. Additionally, he noted changes in bowel habits, including decreased frequency, bloating, and early satiety after food or water intake. Four months earlier, he had a SARS-CoV-2 infection, followed by an unintentional weight loss of 12 kg, attributed to work stress.

He denied changes in dietary habits, former or current use of alcohol, tobacco, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, or herbal supplements. Furthermore, he denied similar previous episodes but had a family history of gastric cancer; his father was diagnosed at the age of 45.

Despite a visit to his family doctor, where he was initially prescribed Omeprazole and Levosulpiride, the pain persisted, only partially responding to Esomeprazole and Alginate. An abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatic steatosis.

During the physical examination, the patient appeared awake, alert, and oriented, with normal vital signs. The digital rectal exam showed no abnormalities, and the stool appeared normal. Blood tests indicated microcytic hypochromic anemia, with a hemoglobin drop from 14.7 g/dL to 12.7 g/dL. Other results included a normal BUN-to-creatinine ratio, an elevated INR of 1.88, a Quick index of 43%, and a prolonged Prothrombin time of 20.4%.

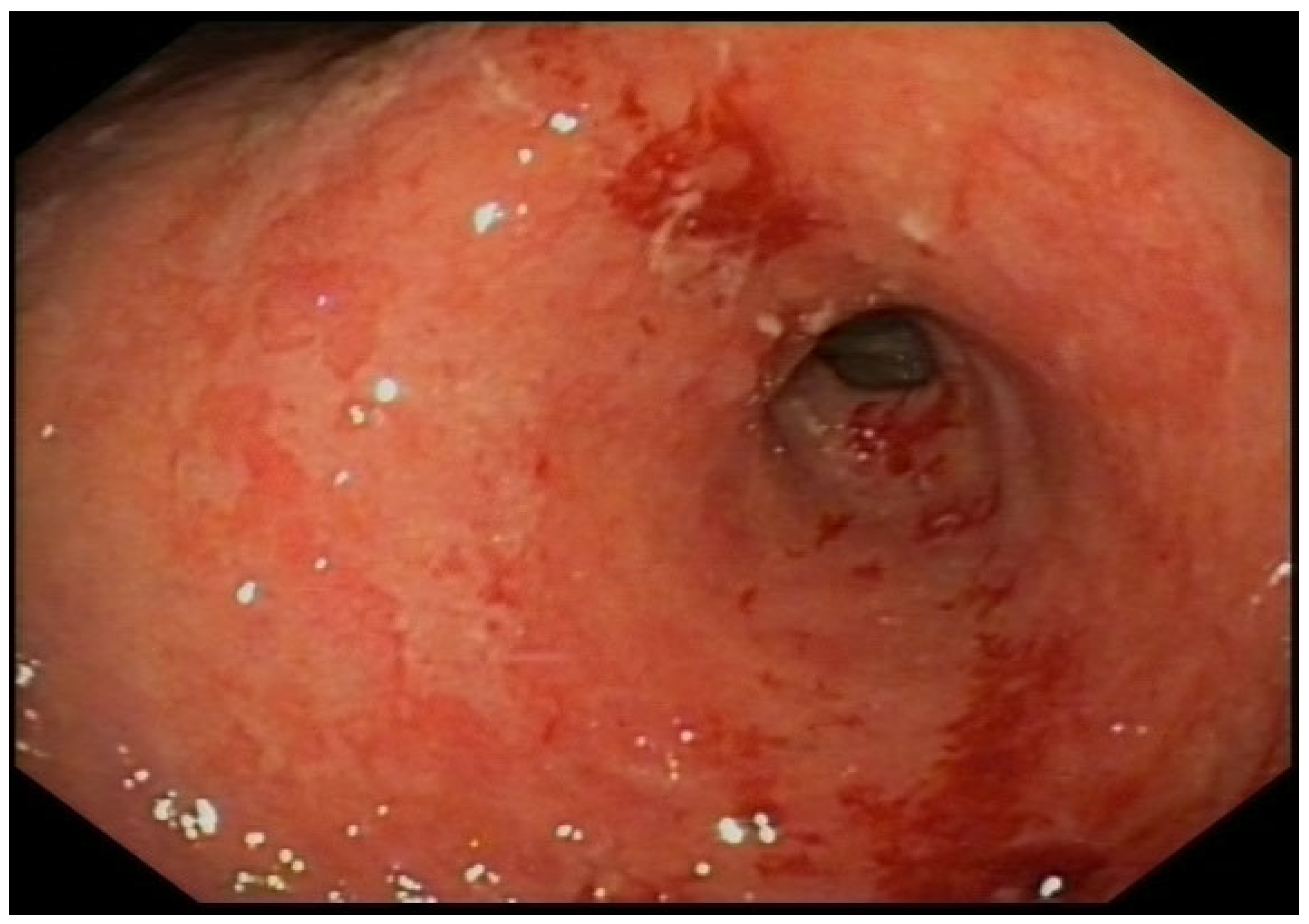

With a suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding (Glasgow – Blatchford bleeding score of 3), the patient received intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) and fluid resuscitation. An urgent gastroscopy revealed a thickened, granular, and irregular mucosa on the incisura angularis, with fibrin remnants and a slightly depressed center containing adherent clots. Patient underwent epinephrine (1:10.000) and aethoxysklerol injections, showing no active bleeding. The mucosa of the antrum, extending along the lesser curvature and distal body presented with edema, erythema, and friability, with a denuded appearance. Only the incisura was biopsied.

Figure 1.

Erythematous and edematous antrum with an ulcerated lesion on the lesser curvature.

Figure 1.

Erythematous and edematous antrum with an ulcerated lesion on the lesser curvature.

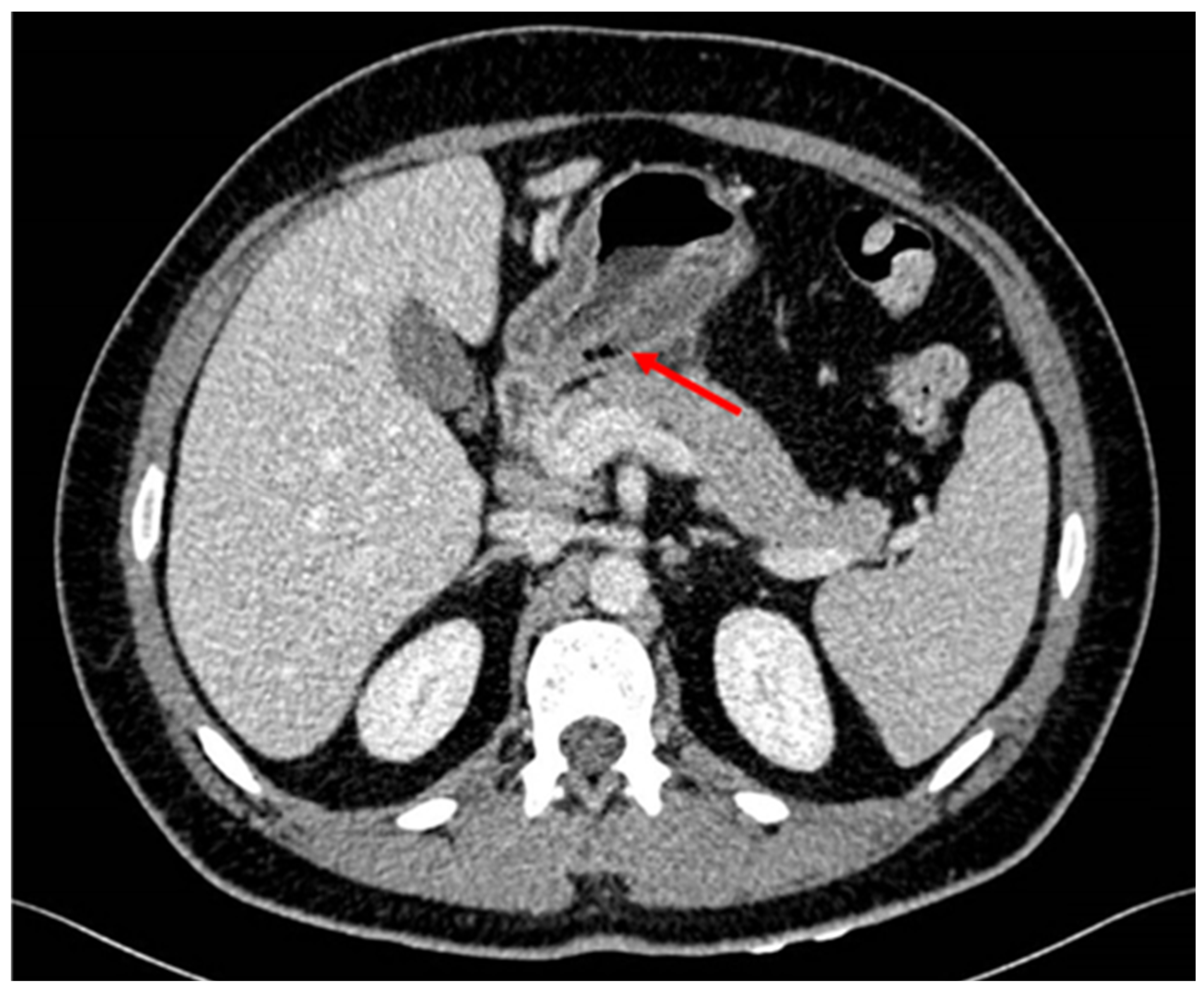

Patient was hospitalized in the Gastroenterology ward with suspicion of malignancy after evaluating endoscopy features. For extension screening a CT scan was performed showing wall thickening of the gastric antrum with intramural gas bubbles. Intramural gas could be possibly related to ulceration or to the previous biopsies. There was slight fat stranding as well as some sub centimeter and non-specific lymph nodes. No signs of distal spreading were seen on the thorax or rest of the abdomen. Tumor markers were negative.

A second programmed endoscopy was performed to take more biopsies of the rest of the gastric wall and re-evaluate the mucosa after 48 h of PPI continuous intravenous infusion. Subcardial area, fornix and proximal body had no significant abnormalities. The lesser curvature of the distal body, incisura angularis and antrum showed a thickened erythematous mucosa, presenting ulcerated and friable areas and bleeding remains. Some mucosal areas had a neoplastic appearance. Multiple biopsies were taken with a harder feeling than normal, suggesting acute erosive gastropathy of a probable neoplastic etiology.

Figure 2.

Thickening of the wall of the gastric antrum showing some atypical gas bubles.

Figure 2.

Thickening of the wall of the gastric antrum showing some atypical gas bubles.

A subsequent phone call from the national blood transfusion donation center informed the patient of a positive syphilis result from a donation three weeks earlier. Despite previous negative serologies in April 2014, the patient, in a stable relationship for five years, confirmed previous sexual intercourse using barrier methods.

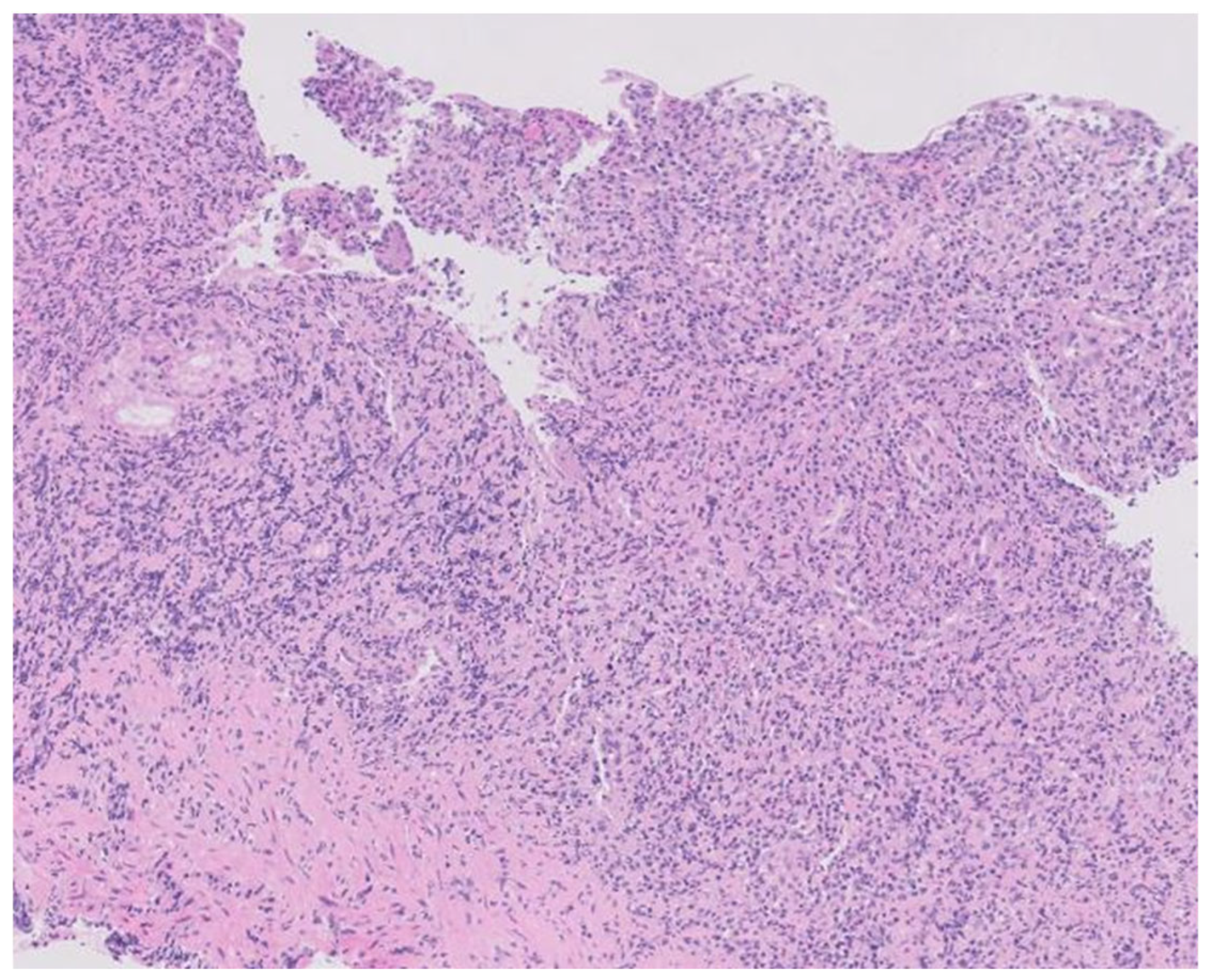

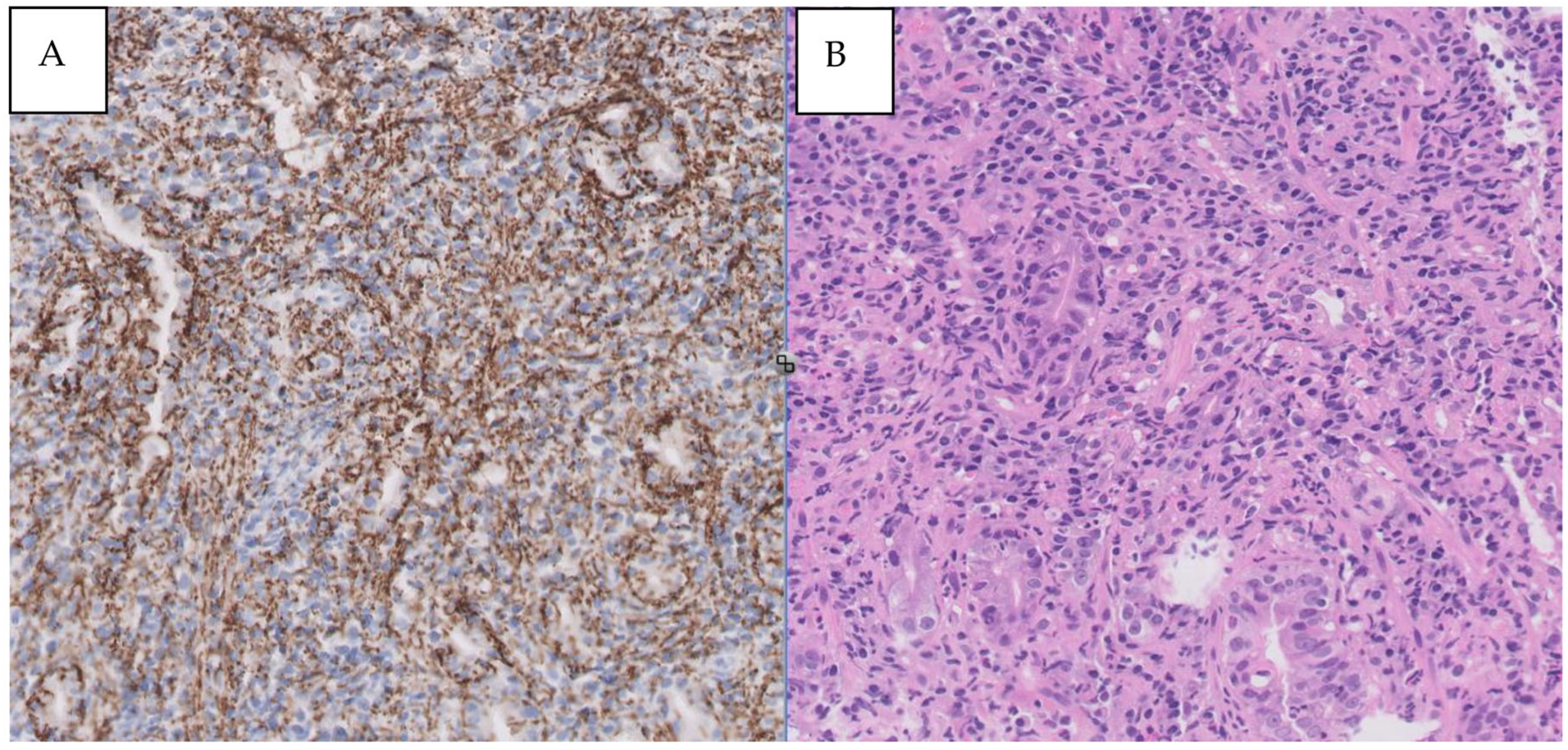

Confirmed syphilis infection prompted treatment with a single dose of 2.4 million units of intramuscular penicillin. Serologies for HIV and hepatitis C were negative, with confirmed protection against HAV and HBV. Gastric tissue biopsy results revealed ulcerated mucosa with a dense inflammatory infiltrate, while immunohistochemistry detected numerous Treponema pallidum spirochetes. Helicobacter pylori bacilli were also identified. The final diagnosis was syphilitic gastritis.

Figure 3.

Histopathology of the gastric lesions revealing dense and diffuse lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation in the lamina propria with effacement of the normal architecture (hematoxylin-eosin staining, X100).

Figure 3.

Histopathology of the gastric lesions revealing dense and diffuse lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation in the lamina propria with effacement of the normal architecture (hematoxylin-eosin staining, X100).

Figure 4.

A- Syphilitic involvement of stomach: dense and mixed mucosal infiltrate. B- Immunohistochemical staining for T. pallidum showing numerous spirochetes (X400).

Figure 4.

A- Syphilitic involvement of stomach: dense and mixed mucosal infiltrate. B- Immunohistochemical staining for T. pallidum showing numerous spirochetes (X400).

During hospitalization, our patient experienced bilateral myodesopsia. Ophthalmological examination found bilateral papilledema, without any indications of ocular syphilis. A brain magnetic resonance imaging scan showed no significant intracranial abnormalities, and a normal neurological examination was conducted. A lumbar puncture was performed, revealing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with elevated total protein levels of 62 mg/dL, glucose at 58 mg/dL, and a cell count of 53 leucocytes/mm3 (80% monocytes and 20% polymorphonucleocytes).

Upon ophthalmological reevaluation, signs of anterior uveitis were identified. Early neurosyphilis was suspected, leading to a prescribed treatment of aqueous penicillin G at 3 to 4 million units intravenously every four hours for 14 days.

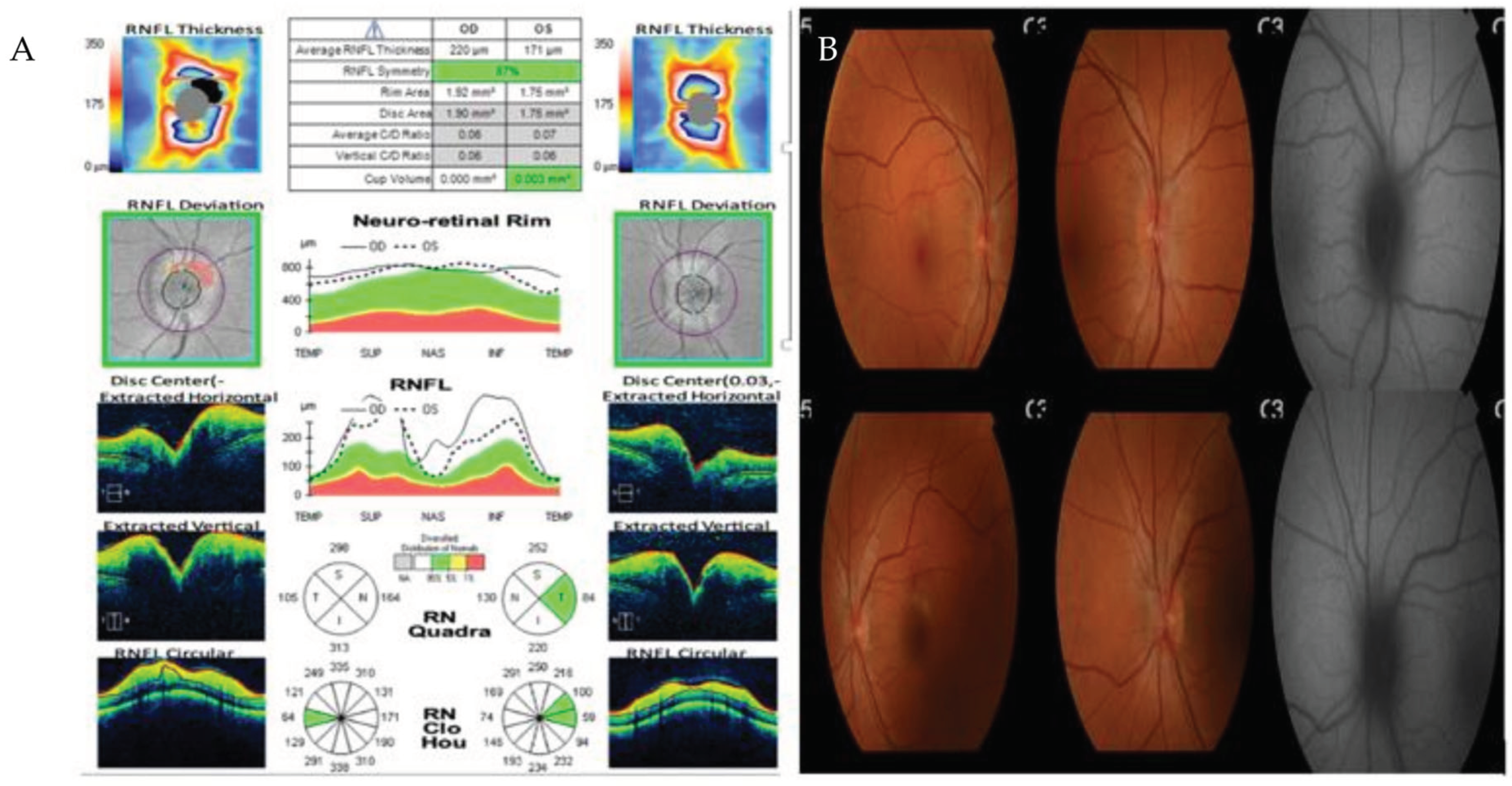

Figure 5.

A – Optic Coherence Tomography showing thickening of all retinal layers. B- Retinography with bilateral papilledema.

Figure 5.

A – Optic Coherence Tomography showing thickening of all retinal layers. B- Retinography with bilateral papilledema.

A transthoracic echocardiogram was conducted, showing normal results. Conventional treatment with Omeprazole, Amoxicillin, Clarithromycin, and Metronidazole was administered, successfully eradicating H. pylori.

Post-treatment, the patient became asymptomatic and was discharged. Subsequent outpatient clinic follow-up included a control gastroscopy, where a normal mucosa with no signs of ulceration was described. Multiple biopsies were taken, indicating chronic gastritis without activity, and no evidence of metaplasia or dysplasia. The Warthin-Starry stain was negative for H. pylori, and immunohistochemistry for Treponema pallidum showed no spirochetes.

Discussion

Gastric involvement by Treponema pallidum is an uncommon manifestation of this bacteria that can occur in infected patients and has been studied for decades (12,13). Although syphilis is primarily known to affect the genital organs, it can also affect other systems of the body, including the gastrointestinal system. In this discussion, various aspects related to gastric syphilis will be explored.

One aspect to consider is the variety of symptoms that may present in patients with gastric syphilis. The main symptoms include vomiting, epigastric pain, weight loss, early satiety, or anorexia (3,4,5,6,8,10). These described symptoms are nonspecific, so without clinical suspicion, finding gastric syphilis in an endoscopic procedure is rare and unexpected (4). Therefore, this can lead to a misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

Gastric involvement in its initial stage usually presents with upper gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to ulceration, followed by a process of obliterative endarteritis characterized by ischemia (8), which can manifest endoscopically as erythema, edema, ulcerations, or nodular mucosa (9,10).

A high index of clinical suspicion is required to consider syphilis as the cause of gastrointestinal symptoms. The initial diagnosis should be made using treponemal and non-treponemal tests, but the final diagnosis will be made by taking biopsies demonstrating the presence of Treponema pallidum with immunohistochemical techniques (7,8).

It is important to emphasize that both the symptomatology, imaging tests, and endoscopic findings can mimic other diseases such as tumors, Crohn’s disease, or lymphomas (2,8,9), making their final diagnosis difficult without pathological anatomy tests.

Once diagnosed, treatment is usually favorable with penicillin, leading to resolution of the lesion in most cases (4,7). It is crucial to initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent serious complications, such as gastric perforation or hemorrhage.

Conclusion

The diagnostic suspicion of gastric syphilis should be considered in patients with risk factors for sexually transmitted infections who present with nonspecific gastric lesions that may be suspicious for malignancy, especially in young patients with a gastric tumor incidence typically below 10% (11). This is due to its nonspecific presentation.

The patient in our case presents with a gastric lesion that can easily be confused with a tumor-like growth of malignant etiology. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive evaluation including specific tests for syphilis to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure proper patient management.

References

- Chaudhry S, Akinlusi I, Shi T, Cervantes J. Secondary Syphilis: Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnostic Testing. Venereology 2023; 2(2):65-75. [CrossRef]

- Lan YM, Yang SW, Dai MG, Ye B, He FY. Gastric syphilis mimicking gastric cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(26): 7798-7804. [CrossRef]

- Sinagra E, Macaione I, Stella M, Shahini E, Maida M, Pompei G, Rossi F, Conoscenti G, Alloro R, Di Ganci S, et al. Gastric Syphilis Presenting as a Nodal Inflammatory Pseudotumor Mimicking a Neoplasm: Don’t Forget the Treponema! Case Report and Scoping Review of the Literature of the Last 65 Years. Gastroenterology Insights 2023; 14(2):178-190. [CrossRef]

- Cai J, Ji D, Guan JL. Gastric syphilis. IDCases. 2017 Apr 26;8:87-88. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto K, Hatakeyama S, Umezawa M, Hayashi S. Gastric syphilis: The great imitator in the stomach. IDCases. 2018 Mar 21;12:97-98. [CrossRef]

- Mylona EE, Baraboutis IG, Papastamopoulos V, Tsagalou EP, Vryonis E, Samarkos M, Fanourgiakis P, Skoutelis A. Gastric syphilis: a systematic review of published cases of the last 50 years. Sex Transm Dis. 2010 Mar;37(3):177-83. [CrossRef]

- Verma R, Al Elshafey M, Oza T, Azouz A, White C. A Giant Syphilitic Gastric Ulcer. ACG Case Rep J. 2022 Jul 11;9(7):e00819. [CrossRef]

- Souza Varella Frazão M, Guimarães Vilaça T, Olavo Aragão Andrade Carneiro F, Toma K, Eliane Reina-Forster C, Ryoka Baba E, Cheng S, Ferreira de Souza T, Guimarães Hourneaux de Moura E, Sakai P. Endoscopic aspects of gastric syphilis. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:646525. [CrossRef]

- Long BW, Johnston JH, Wetzel W, Flowers RH 3rd, Haick A. Gastric syphilis: endoscopic and histological features mimicking lymphoma.

- Cao J, Zhu J, Xiang Y, Peng P, Liu Q, Fu H, Huang Y. Gastric Syphilis Mimicking Lymphoma: A Case Report. Infect Drug Resist. 2023 Jul 11;16:4539-4544. [CrossRef]

- Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, Maciejewski R, Sitarz R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 4;21(11):4012. [CrossRef]

- Morton CB. Syphilis of the stomach. Archives of Surgery 1932;25(5):880–889. [CrossRef]

- Graham EA. Surgical treatment of syphilis of the stomach. Ann Surg 1922; 76: 449-456. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).