Submitted:

21 February 2024

Posted:

22 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Target population and sampling procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Research design

2.4. Ethics approval and consent to participate

2.5. Data analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freudenberger, H. J. Staff burnout. The Journal of Social Issues 1974, 30(1), 159-166. 1. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. E. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior 1981, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, K.K.; Navarro, B.C.; Carpio, J.; Durán, M. (2023). Síndrome de burnout en profesionales educativos. Horizontes. Revista de Investigación en Ciencias de la Educación 2023, 7(28), 690-697. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Leiter, M. P. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcés de Los Fayos, E. J. Frecuencia de burnout en deportistas jóvenes: estudio exploratorio. Revista de Psicología del Deporte 1993, 4, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés de los Fayos, E. J. Burnout en niños y adolescentes: Un nuevo síndrome en psicopatología infantil. Psicothema 1995, 7(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, R.A.; Prieto, D.E. Revisión sistemática sobre la prevalencia del síndrome de Burnout en el sector académico. Revista de Investigación en Psicología 2021, 24(2), 163-182. [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, M. A.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A. Síndrome de burnout académico en estudiantes universitarios: una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicopatología y Salud Mental del Niño y del Adolescente 2022, 25(1), 1-18.

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; González-Gutiérrez, J.L.; Garrosa, E. Variables de personalidad y proceso del Burnout: personalidad resistente y sentido de la coherencia. Revista Interamericana de Psicología Ocupacional 2001, 20(1), 1-18.

- Santes, M.C.; Meléndez, S.; Martínez, N.; Ramos, I.; Preciado, M.L.; Pando, M. La salud mental en enfermería. Revista Chilena de Salud Pública 2019 13(1), 23-29.

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Harper, W.; Moutier, C.: Durning, S.J.; Power, D.V.; Massie, F.S.; … Shanafelt, T.D. A Multi-institutional Study Exploring the Impact of Positive Mental Health on Medical Students’ Professionalism in an Era of High Burnout. Academy Medical 2012 87, 1024–1031. [CrossRef]

- Marenco, A.; Suárez-Colorado, Y.; Palacio-Sañudo, J. Burnout académico y síntomas relacionados con problemas de salud mental en universitarios colombianos. Psychologia 2017, 11(2), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moreno, J. A.; López-Zafra, E.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R. Síndrome de burnout académico en estudiantes universitarios: Un estudio comparativo entre estudiantes de primer y último curso. Revista de Psicopatología y Salud Mental del Niño y del Adolescente 2015 18(2), 167-177.

- Kim, B.; Jee, S.; Lee, J.; An, S.; Lee, S. M. Relationships between social support and student burnout: A meta-analytic approach. Stress and Health 2018, 34(1), 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés de Los Fayos, E. J. Burnout en deportistas: Un estudio de la influencia de variables de personalidad, sociodemográficas y deportivas en el síndrome (Tesis doctoral); Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, 1999.

- Girón, M.D.C.; Calderón, N. Síndrome de Burnout académico en estudiantes del primer año y último año de la escuela de Psicología de una universidad particular de Piura (Tesis doctoral); Universidad de Antenor Orrego: Perú, 2023.

- Chahua, A.D.L.A. Burnout estudiantil y calidad de vida en estudiantes de psicología de una universidad privada de Lima Sur (Tesis Doctoral); Universidad Autónoma del Perú: Perú, 2022.

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. E.; Leiter, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Martínez, I. M.; Pinto, A. M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A. B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A crossnational study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2002, 33(5), 464-481. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. The NEO-PI/NEO-FFI manual supplement. Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, F, 1989.

- Cordero, A.; Pamos, A.; Seisdedos, N. Adaptación Española del NEO-FFI. En Inventario de Personalidad NEO revisado (NEO-PI-R), Inventario NEO reducido de cinco factores (NEO-FFI): Manual profesional; Costa, P.T,McCrae, R.R. (Eds); TEA: Madrid, 2008.

- Ato, M.; López, J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología 2013, 29(3), 1038-1059. [CrossRef]

- Akbasli, S.; Arastaman, G.; Feyza, G. Ü. N.; Turabik, T. School engagement as a predictor of burnout in university students. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 2019, 45(45), 293-309. [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, N.D.; Dissanayake, D.S.; Abeywardena, G.S. Validity and reliability of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-student survey in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychology 2018, 6(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | Min | Max | t | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | E.C. Educ. | 20.93 | 1.53 | 18.0 | 25.0 | 3.72 | <.001 | .302 |

| Nursing | 20.44 | 1.73 | 18.0 | 25.0 | ||||

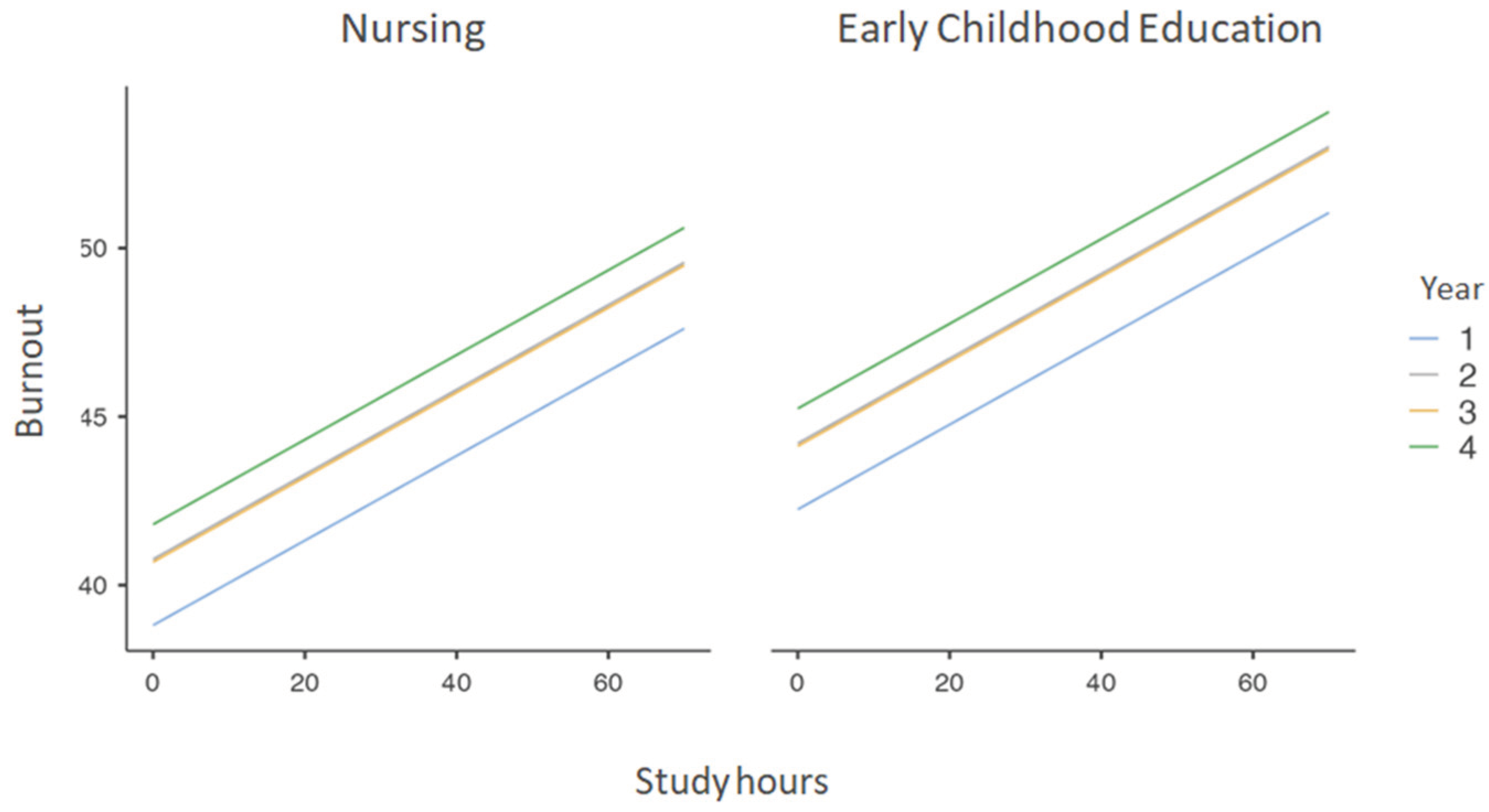

| Study hs | E.C. Educ. | 6.87 | 6.79 | 0.0 | 68.0 | -6.15 | <.001 | .500 |

| Nursing | 10.83 | 8.90 | 0.0 | 70.0 | ||||

| Sleep hs | E.C. Educ. | 7.25 | 2.01 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 2.26 | .024 | .184 |

| Nursing | 6.94 | 1.18 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Average grade | E.C. Education | Nursing | Statistics | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | 1 | (33.3%) | 2 | (66.7%) | 25.7 | <.001 |

| C | 43 | (31.6%) | 93 | (68.4%) | ||

| B | 242 | (55.3%) | 196 | (44.7%) | ||

| A | 15 | (65.2%) | 8 | (34.8%) | ||

| Media | DE | Mín | Máx | t | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

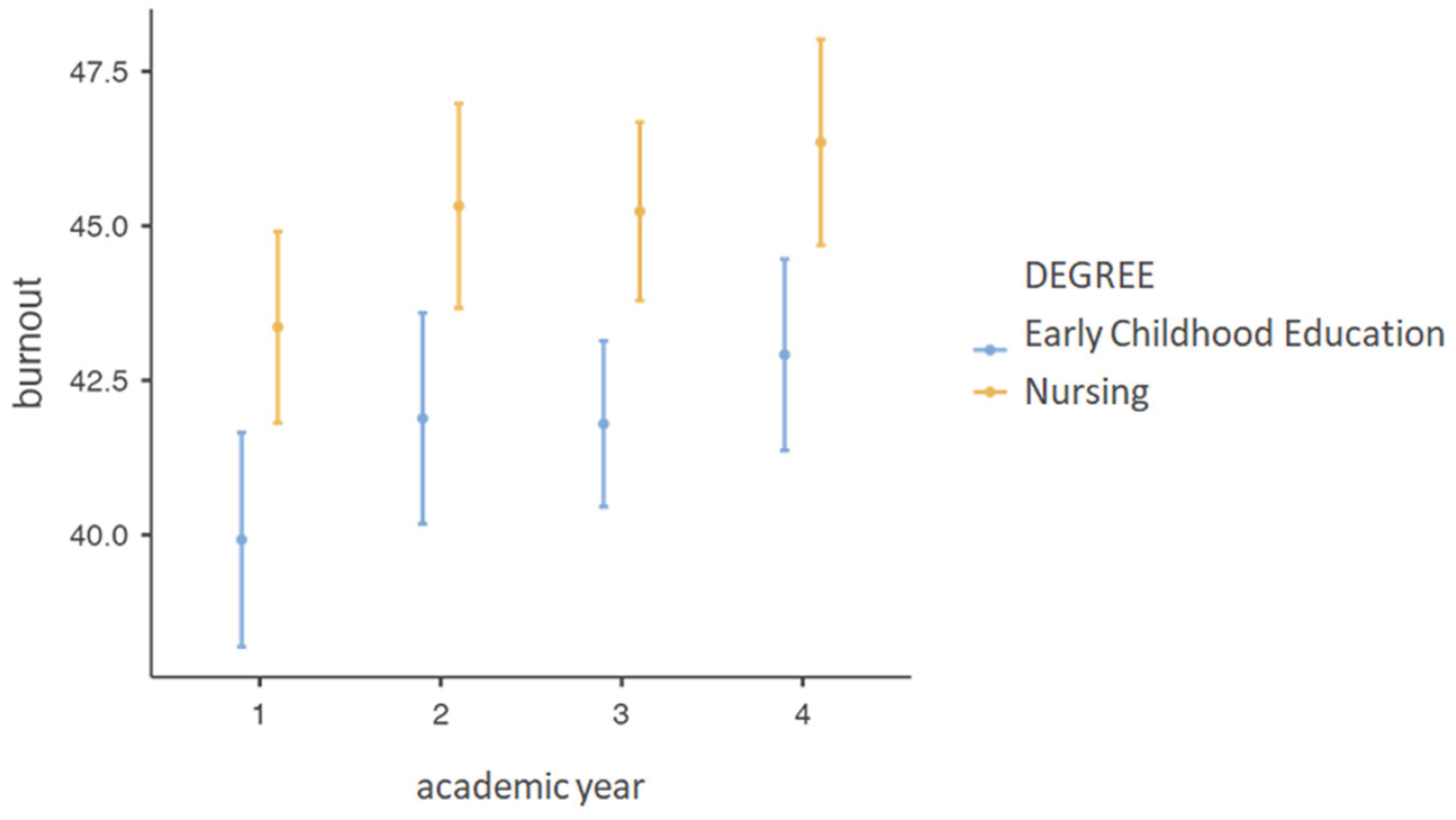

| Burnout | E.C. Educ. | 41.58 | 7.82 | 18.00 | 65.0 | -5.07 | <.001 | -.412 |

| Nursing | 45.17 | 9.55 | 23.00 | 90.0 | ||||

| Emotional exhaustion | E.C. Educ. | 9.69 | 5.62 | 0.00 | 27.0 | -9.35 | <.001 | -.760 |

| Nursing | 14.28 | 6.43 | 1.00 | 30.0 | ||||

| Deperson | E.C. Educ. | 4.55 | 3.98 | 0 | 19 | 1.92 | .056 | .156 |

| Nursing | 3.90 | 4.37 | 0 | 24 | ||||

| Personal accomplish | E.C. Educ. | 27.34 | 4.65 | 11.00 | 36.0 | .89 | .374 | .072 |

| Nursing | 26.99 | 4.88 | 11.00 | 36.0 | ||||

| Neuroticism | E.C. Educ. | 19.95 | 8.18 | 0.00 | 47.0 | -2.12 | .034 | .072 |

| Nursing | 21.36 | 8.20 | 1.00 | 43.0 | ||||

| Extraversion | E.C. Educ. | 34.21 | 6.91 | 15.00 | 48.0 | .45 | .654 | .364 |

| Nursing | 33.96 | 6.80 | 9.00 | 48.0 | ||||

| Openness | E.C. Educ. | 27.91 | 6.35 | 13.00 | 44.0 | -2.43 | .015 | .198 |

| Nursing | 29.16 | 6.31 | 12.00 | 48.0 | ||||

| Agreeableness | E.C. Educ. | 31.43 | 5.85 | 11.00 | 46.0 | -.81 | .419 | -.066 |

| Nursing | 31.82 | 5.86 | 12.00 | 46.0 | ||||

| Conscientious. | E.C. Educ. | 31.58 | 6.56 | 15.00 | 48.0 | -.17 | .865 | -.014 |

| Nursing | 31.67 | 6.59 | 11.00 | 47.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).