1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [1] or [2,3], or [4,5,6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

2. Materials and Methods

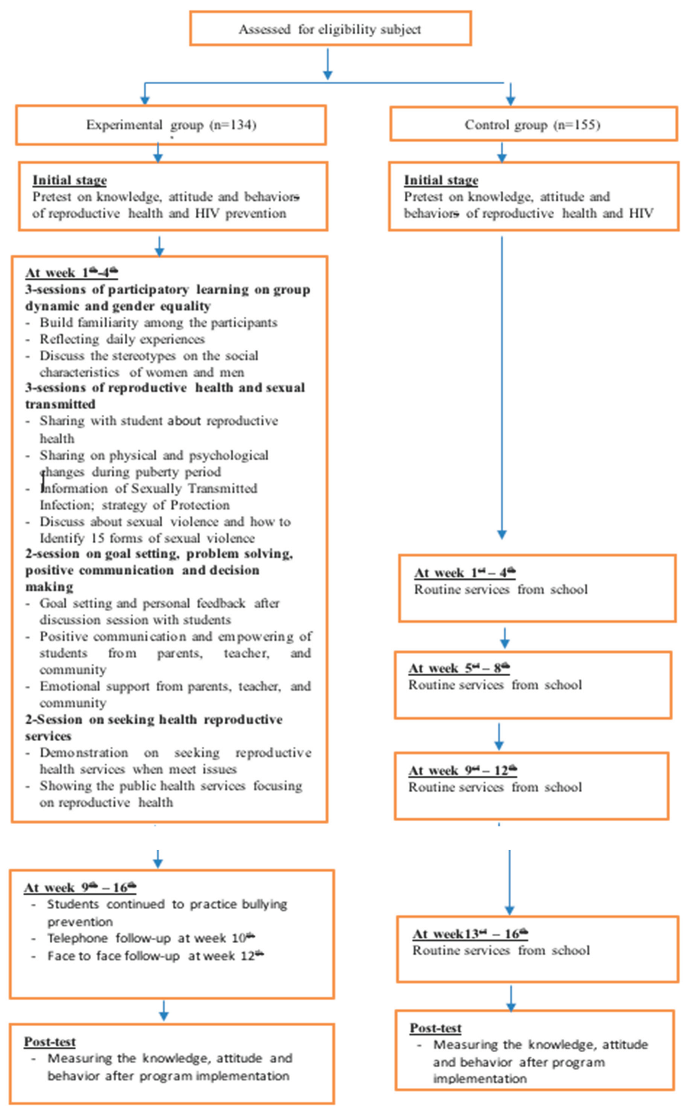

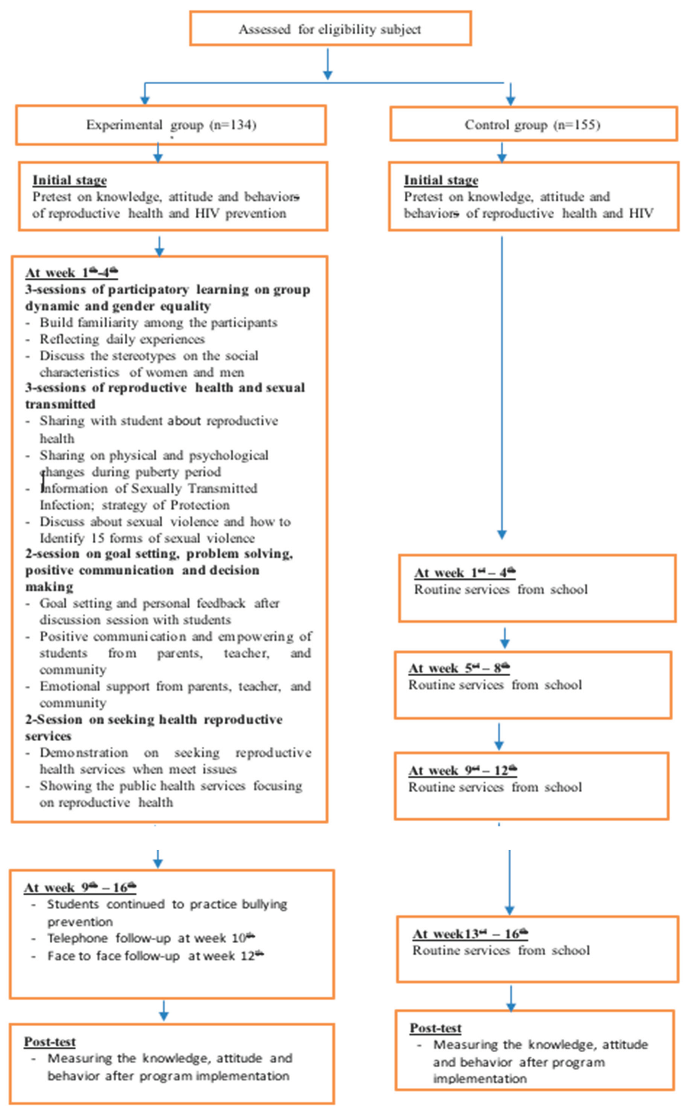

Design

The design in this study uses a Quasi-experiment with two groups. Pre-Test and Post-Test with non-equivalent control group. The intervention group will receive Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention while the control group receives usual care.

Setting

The research was conducted in the West Papua Province, We focused into three districts namely Manokwari, Sorong and Fak-fak which is the high number of HIV

Sample, Sample Size and sampling technique

Two hundred and fifty-eight samples were selected using the purposively sampling technique. We divided into the experimental group (n=134) and the control group (N=155). The intervention group received the Five session of sexual reproductive health school-based HIV prevention program and the control group receives usual care from the school. The criteria for inclusion of selecting the samples including: 1) age from 15 to 19 years, 2) willingness to participate in this study, and 3) No cognitive impairment. Students who getting sick and not complete the program were excluded in this study.

Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention

The Sexual Reproductive Health School-Based HIV Prevention program is an educational initiative designed to promote awareness, knowledge, and skills related to sexual and reproductive health, as well as HIV prevention, among school-age individuals. This program typically takes place within the context of educational institutions, such as schools and colleges, and aims to empower young people with accurate information about sexual health, reproduction, and the prevention of HIV/AIDS. The program was was conducted over six months in the West Papua Province, from July 2022 to December 2022.

In this study, developing a comprehensive sexual reproductive health (SRH) and school-based HIV prevention program is critical to enhancing students' well-being and giving them the knowledge and skills in order to make informed sexual health decisions. The program consisted of 6 session as follows: (1) Group Dynamics: In group dynamics starts with introduction, then there's hope and commitment and ends with a study contract; (2) Gender equality: this game introduces self-concepts of women and men; (3) Reproductive health: each group of games is introduced to puberty, myths or facts about reproductive health, and pregnancy; (4) Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexual Violence: carried out in the form of exposure about HIV and sexually transmitted infections. To violence students are introduced with several games: forms of sexual violence, prevention of sexual abuse, first aid to sexual violence; (5) Communication: each student in the couple will talk about reproductive health, decision-making and how to get reproductive information through the internet; (6) Reproductive Health Services: provide an opportunity to conduct group discussions on how to obtain reproduct.

3. Results

Table 1 describes the representation of the demographic data collected from three different districts: Manokwari, Fak-fak, and Sorong. The table is divided into several categories, including school type, school status, class, gender, religion, and ethnicity. Each category is further divided into subcategories, and the frequency (F) and percentage (%) of each subcategory are provided for both control and intervention groups in each district. In the table, the frequency (F) and percentage (%) of students attending each type of school are listed. In the Manokwari District control group, 40 students (70.2%) attend high school, while 17 students (29.8%) attend vocational school.

For instance, in the Manokwari District control group, 37 students (64.9%) are enrolled in public school, while 20 students (35.1%) are in private school. The intervention group in the same district has a slightly higher percentage of students in public schools (71.4%) compared to the control group. The class is divided into three categories: 10, 11, and 12. In the Manokwari district, the distribution of students across these classes is fairly even, with a slightly higher percentage in class 11 (38.6% in the control group and 38.8% in the intervention group). In the Fak-fak district, the majority of students are in class 11 (60.8% in the control group and 53.2% in the intervention group). In the Sorong district, the majority of students are also in class 11 (63.8% in the control group and 47.4% in the intervention group).

In the Manokwari district, there are more non-Papua students in both the control group (57.9%) and the intervention group (75.5%). In the Fak-fak district, there are more Papua students in both the control group (58.8%) and the intervention group (65.9%). In the Sorong district, there are more non-Papua students in both the control group (74.5%) and the intervention group (71.1%).

Table 3.

1. Data Demographic.

Table 3.

1. Data Demographic.

| No |

Charateristic |

|

Manokwari District |

Fak – fak District |

Sorong District |

| Control group (n=57) |

Intervention group (n=49) |

Control group (n=51) |

Intervention group

(n=47)

|

Control group

(n=47)

|

Intervention group

(n=-38)

|

| F |

% |

F |

% |

F |

% |

F |

% |

F |

% |

F |

% |

| 1 |

School Type |

High school |

40 |

70.2 |

35 |

71.4 |

35 |

68.6 |

33 |

72.2 |

41 |

87.2 |

32 |

84.2 |

| Vocational |

17 |

29.8 |

14 |

28.6 |

16 |

31.4 |

14 |

29.8 |

6 |

12.8 |

6 |

15.8 |

| 2 |

School status |

Public school |

37 |

64.9 |

35 |

71.4 |

19 |

37.3 |

24 |

51.1 |

27 |

57.5 |

21 |

55.3 |

| Private school |

20 |

35.1 |

14 |

28.6 |

32 |

62.7 |

23 |

38.9 |

20 |

42.5 |

17 |

44.7 |

| 3 |

Class |

Grade 10 |

12 |

21.0 |

20 |

40.8 |

9 |

17.6 |

8 |

17.0 |

4 |

8,5 |

6 |

15.8 |

| Grade 11 |

22 |

38.6 |

19 |

38.8 |

31 |

60.8 |

25 |

53.2 |

30 |

63.8 |

18 |

47.4 |

| Grade 12 |

23 |

40.4 |

10 |

20.4 |

11 |

21.6 |

14 |

29.8 |

13 |

27.7 |

14 |

36.8 |

| 4 |

Gender |

Male |

15 |

26.3 |

27 |

55.1 |

25 |

49 |

24 |

51.1 |

26 |

55.3 |

23 |

60.5 |

| Female |

42 |

73.7 |

22 |

44.9 |

26 |

51 |

23 |

48.9 |

21 |

44.7 |

15 |

39.5 |

| 5 |

Religion |

Islam |

20 |

35.1 |

26 |

53.1 |

24 |

47.0 |

20 |

42.6 |

26 |

55.3 |

20 |

52.6 |

| Christian Protestant |

35 |

61.4 |

20 |

40.8 |

16 |

31.4 |

17 |

36.2 |

14 |

29.8 |

12 |

31.6 |

| Catholic Christian |

2 |

3.5 |

3 |

6.1 |

11 |

21.6 |

10 |

21.2 |

7 |

14.9 |

6 |

15.8 |

| 6 |

Ethnic |

Papua |

24 |

42.1 |

12 |

24.5 |

30 |

58.8 |

31 |

65..9 |

12 |

25.5 |

11 |

28.9 |

| Non-Papua |

33 |

57.9 |

37 |

75.5 |

21 |

41.2 |

16 |

34.1 |

35 |

74.5 |

27 |

71.1 |

Mean difference of Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among intervention groups before and after receiving Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention program.

Table 2 elucidated the average disparity in knowledge, attitude, and behavior between the intervention group prior to and after obtaining the Sexual Reproductive Health School-Based HIV Prevention. The study revealed a significant difference in knowledge regarding sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention among adolescents before and after participating in the program in three districts of Papua Island, namely Manokwari district (p-value <.05), Fak-Fak district (p-value <.05), and Sorong district (p-value <.05). The attitudes of teenagers towards reproductive health and HIV prevention demonstrated substantial improvement in two districts, namely Manokwari district (p-value <.05) and Fak-Fak district (p-value <.05). However, there was no significant improvement in the Sorong district before and after receiving the program (p-value > .05). The study found a significant difference in the behavior of sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention across three districts in Papua Island, namely Manokwari district (p-value <.05), Fak-Fak district (p-value <.05), and Sorong district (p-value <.05).

Mean difference of knowledge, subjective norm and attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among groups before and after receiving Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention Program.

Table 3 describes the mean difference in knowledge, attitude, and behavior among control groups before and after receiving the Sexual Reproductive Health School-Based HIV Prevention program. The results found that the knowledge of sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention among the control group was not significantly different before and after receiving the sexual reproductive health school-based HIV program in the three districts in Papua Island, including Manokwari district (p-value >.05), Fak-Fak district (p-value >.05), and Sorong district (p-value >.05). Regarding the attitude toward sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention, there was no significant difference before and after receiving the program among the control group in the Manokwari and Fak-Fak districts (p-value >.05) except in the Sorong district (p-value <.05). In terms of the behavior of sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention in the Manokwari district (p-value <.05), the Fak-Fak district (p-value <.05) was significantly different; however, it was in contrast with the behaviors of sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention in the Sorong district, which were not significantly different before and after receiving the program (p-value >.05)

Table 3.

Mean difference of knowledge, subjective norm and attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among control groups before and after receiving Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention.

Table 3.

Mean difference of knowledge, subjective norm and attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among control groups before and after receiving Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention.

| Variable |

Papua Districts |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

t |

df |

p-value |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Knowledge on reproductive health and HIV prevention |

Manokwari |

3.2870 |

0.3791 |

2.9656 |

0.4371 |

0.7064 |

50 |

0.483 |

| Fak- Fak |

3.0239 |

0.4598 |

3.0021 |

0.47556 |

1.6099 |

50 |

0.113 |

| Sorong |

2.9930 |

0.3073 |

2.8283 |

0.5184 |

1.9458 |

30 |

0.061 |

| Subjective norm and attitude reproductive health and HIV prevention |

Manokwari |

3.2870 |

0.3791 |

2.9656 |

0.4371 |

0.7064 |

50 |

0.483 |

| Fak- Fak |

3.0239 |

0.4598 |

3.0021 |

0.4756 |

1.6099 |

50 |

0.113 |

| Sorong |

2.6886 |

0.4899 |

2.4250 |

0.5180 |

2.4769 |

30 |

0.019 |

| Behavior control on sexual transmitted and HIV prevention |

Manokwari |

3.1665 |

0.4138 |

2.6911 |

0.3521 |

8.1434 |

56 |

0.000 |

| Fak- Fak |

2.9586 |

0.4546 |

2.9586 |

0.4496 |

0.0000 |

50 |

0.000 |

| Sorong |

2.7120 |

0.3407 |

2.8233 |

0.5041 |

-1.1704 |

30 |

0.251 |

Mean difference of knowledge, subjective norm, attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among intervention groups before and after receiving the Sexual Reproductive Health School-Based HIV Prevention program

The results of this study showed the mean difference in knowledge, subjective norms and attitudes, and behavioral control of sexual reproductive health and HIV prevention among the intervention groups before and after receiving the Sexual Reproductive Health School-Based HIV Prevention was significantly different in 3 districts of West Papua Island, including Manokwari district (p-value <.05), Fak-Fak district (p-value <.05), and Sorong district (p-value <.05).

Before the intervention, students' knowledge about HIV/AIDS may vary, with some holding misconceptions about transmission routes and prevention methods. In this study, some strategies were used, such as two sessions of participatory learning on group dynamics and gender equality; 3-sessions of discussion on reproductive health and sexual transmission; 2-session on goal setting, problem solving, positive communication, and decision-making; and 2-Session on seeking reproductive health services. From that, strategies improved the understanding of respondents in reproductive health and HIV prevention.

Participatory learning is an educational approach that emphasizes active involvement and collaboration among students in the learning process. It has been shown to have a significant impact on group dynamics and gender equality. Participatory learning is an educational approach that emphasizes active involvement and collaboration among students in the learning process. It has been shown to have a significant impact on group dynamics and gender equality [8]

In terms of gender equality, participatory learning and action (PLA) can be instrumental in empowering both women and men. PLA includes examples of participatory development initiatives that take a gender perspective and seek to address issues of gender equality [9]. Participatory approaches in gender equality and gender-based violence research with refugees and internally displaced populations have been shown to involve participants in the design, data collection, and analysis, thereby enhancing their agency and voice [10]. This can help counteract often romanticized perceptions and representations, particularly of women, and promote a more nuanced understanding of gender issues.

The importance of goal setting, problem-solving, positive communication, and decision-making on the attitudes and behaviors of HIV prevention among students is a critical area of focus in public health. These elements play a significant role in shaping effective HIV prevention strategies, particularly in educational settings where young people are at a formative stage regarding their attitudes and behaviors towards health. Goal setting is a core component of effective HIV prevention. The "Keep It Up! 2.0" prevention trial demonstrated that young men who have sex with men (YMSM) engaged in goal setting as part of their HIV prevention efforts, focusing on strategies for safer sex. This approach allowed participants to create realistic and practical plans for HIV prevention, emphasizing the importance of setting specific, achievable goals for promoting safer sexual behaviors[11].

The Social Problem-Solving (SPS) model offers a framework for addressing challenges related to HIV medication adherence, a crucial aspect of HIV prevention. This model highlights the importance of constructive problem-solving styles in improving health outcomes and adjustment. Interventions based on the SPS model can be tailored to address HIV-specific challenges, such as loss of social support and healthcare decision-making, potentially improving psychological well-being and medication adherence among HIV-positive individuals [12].

Communication factors play a significant role in influencing college students' attitudes and behaviors towards HIV testing. Cognitive and emotional self-efficacy, along with motivational factors, are influenced by how HIV testing is communicated. Students are more receptive to HIV testing messages that are conveyed through social media and other mediated channels, suggesting that effective communication strategies can positively impact students' willingness to undergo HIV testing [13].

Decision-making processes regarding HIV prevention and treatment scale-up highlight the complexity of allocating resources efficiently. The gap between theory and practice in decision-making underscores the need for practical tools that support evidence-based decisions. This is particularly relevant in the context of HIV prevention among students, where decisions about which interventions to implement can significantly impact the effectiveness of prevention efforts [14].

Thereby, goal setting, problem-solving, positive communication, and decision-making are integral to shaping positive attitudes and behaviors towards HIV prevention among students. These elements contribute to the development of effective prevention strategies by promoting safer sexual behaviors, improving medication adherence, enhancing communication about HIV testing, and facilitating evidence-based decision-making in HIV prevention.

Previous studies also documented that even among medical students, there can be incorrect knowledge about HIV transmission, such as the belief that the virus can be transmitted by using a public toilet or sharing a glass [15]. After the intervention, there should be an observable increase in accurate knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Effective school-based interventions have been shown to improve students' understanding of HIV transmission, prevention measures, and attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS [16,17,18]

For example, a study in Iran found that after an educational intervention, female sex workers showed significant improvements in their knowledge about HIV and sexually transmitted infections, as well as in their attitudes and preventive behaviors [19]. Another study also mentioned that the effectiveness of the intervention can be measured through pre- and post-intervention assessments using questionnaires or interviews that evaluate changes in knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and practice (KABP) [20]. These assessments can help determine whether the intervention has successfully increased awareness and understanding of HIV/AIDS among the participants

The mean difference in knowledge, subjective norm, attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention between the intervention group and the control group

To assess the effectiveness of knowledge, attitude, and behavior changes between the intervention group and the control group in the context of sexual reproductive health school-based HIV prevention programs, it's essential to analyze the outcomes of quasi-experimental studies that have been conducted in this area. These studies typically involve pre- and post-intervention assessments to measure changes in HIV/AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among participants.

Studies have demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge about HIV/AIDS following educational interventions. For instance, an educational program based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) showed significant changes in all different constructs of TPB, indicating that school-based educational interventions can effectively enhance students' knowledge about HIV/AIDS prevention. Similarly, a study in Iran found that after an educational intervention, female sex workers showed significant improvements in their knowledge about HIV and sexually transmitted infections [19]

Changes in attitudes towards HIV/AIDS prevention are also a critical outcome of these interventions. In this study, the students received peer education to share information and experiences with their peers, which can contribute to their knowledge and attitudes towards reproductive health. Positive peer influence and discussions may lead to a better understanding of reproductive health issues [4]. Additionally, Self-Initiated learning was also done to educate about reproductive health, leading to a good level of knowledge and positive attitudes even without formal intervention [21]

A study described how the TPB-based educational program mentioned earlier resulted in significant changes in attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and preventive behavior among in-school adolescents [3]. This suggests that educational interventions can protect adolescents from wrong attitudes and risky behaviors, especially where adolescents are at risk of HIV infection.

Behavioral changes, particularly in preventive behaviors related to HIV/AIDS, are among the most crucial outcomes of these interventions. While improving knowledge and attitudes is important, the ultimate goal is to change behavior to reduce the risk of HIV transmission. The study on female sex workers in Iran also reported decreases in risk behaviors following the educational program, indicating the program's success in influencing not just knowledge and attitudes but also actual preventive behaviors [19]

The effectiveness of these interventions is often more pronounced when compared with control groups that did not receive the intervention. For example, a study evaluating a school-based HIV prevention intervention among Yemeni adolescents found that peer education could significantly impact knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards HIV/AIDS prevention [22]

These findings are consistent with other studies that have shown positive changes in HIV-related comprehensive knowledge and risky sexual behaviors among students in the intervention group compared to those in the control group [23]

5. Conclusions

The Sexual Reproductive Health School-Based HIV Prevention Program can effectively increase knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral control related to reproductive health and HIV prevention in the intervention group compared to the control group. These changes are critical to reducing the risk of HIV transmission and highlight the importance of implementing well-designed educational interventions as part of a broader HIV prevention strategy.

Author Contributions

N.G.S; D.P.S and F.M.S. deigned the research, conceptualization, developed instruments and program for data collection. N.G.S and R.A.P. data analysis and writing—original draft preparation. N.M. Data collection and advised on data analysis. A.M. Statistically analysis. S.T.R.T Data collection and Advised on data analysis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethical Review Committee of the Human Research Poltekes Kemenkes Sorong, has approved this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Prof Zahra Saad and Prof. Ce An Ahmad for supporting my study. I Thank also for faculty of Nursing, Mahsa University and Poltekes Kemenkes Sorong for supporting during my study. We also would like to thank the research assistant from Sorong, fak-fak, and Manokwari districts of West Papua.

Conflicts of Interest

We declared no conflict of interest in this manuscript. The funding sponsors also served no role in writing the manuscript or decision to conduct this manuscript.

References

- Malau, C. HIV and development the Papua New Guinea way. Dev. Bull. 2000, 52, 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sianturi, E.I.; Perwitasari, D.A.; Islam, A.; Taxis, K. The association between ethnicity, stigma, beliefs about medicines and adherence in people living with HIV in a rural area in Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faharani, F.K.; Darabi, F.; Yaseri, M. The Effect of Theory-Based HIV/AIDS Educational Program on Preventive Behaviors Among Female Adolescents in Tehran: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2021, 21, 194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tynan, A.; Hill, P.S.; Kelly, A.; Kupul, M.; Aeno, H.; Naketrumb, R.; Siba, P.; Kaldor, J.; Andrew Vallely2,4 for the Male Circumcision Acceptability and Impact Study (MCAIS) team. Listening to diverse community voices: The tensions of responding to community expectations in developing a male circumcision program for HIV prevention in Papua New Guinea. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sianturi, E.I.; Latifah, E.; Probandari, A.; Effendy, C.; Taxis, K. Daily struggle to take antiretrovirals: A qualitative study in Papuans living with HIV and their healthcare providers. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, L.; Numbery, G.; Morin, J. Preventing AIDS in Papua Revised Research Report. 2020.

- Sianturi, E.I.; Latifah, E.; Soltief, S.N.; Sihombing, R.B.; Simaremare, E.S.; Effendy, C.; Probandari, A.; Suryawati, S.; Taxis, K. Understanding reasons for lack of acceptance of HIV programs among indigenous Papuans: A qualitative study in Indonesia. Sex Health 2022, 19, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innovation, C.f.T. Collaborative learning. 2023.

- Kanji, N. Reflections on gender and participatory development. Particip. Learn. Action 2004, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lokot, M.; Hartman, E.; Hashmi, I. Participatory approaches and methods in gender equality and gender-based violence research with refugees and internally displaced populations: A scoping review. Confl. Health 2023, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motley, D.N.; Hammond, S.; Mustanski, B. Strategies Chosen by YMSM During Goal Setting to Reduce Risk for HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections: Results From the Keep It Up! 2.0 Prevention Trial. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2017, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.O.; Elliott, T.R.; Neilands, T.B.; Morin, S.F.; Chesney, M.A. A Social Problem-Solving Model. of Adherence to HIV Medications. Health Psychol. 2006, 25, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.A.; Roy, D.; Dam, L.; Coman, E.N. College students and HIV testing: Cognitive, emotional selfefficacy, motivational and communication factors. J. Commun. Healthc. 2017, 10, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alistar, S.S.; Brandeau, M.L. Decision making for HIV prevention and treatment scale up: Bridging the gap between theory and practice. Med. Decis. Making 2012, 32, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, M.I.; Popa, G.L.; Mihai, A.; Ocneanu, M.; Diaconu, A. HIV and AIDS, among knowledge, responsibility and ignorance; a study on medical students at the end of their first universitary year. J. Med. Life 2009, 2, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fonner, V.A.; Armstrong, K.S.; Kennedy, C.E.; O'Reilly, K.R.; Sweat, M.D. School based sex education and HIV prevention in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, L.; Yaya, S. The effect of HIV educational interventions on HIV-related knowledge, condom use, and HIV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Salam, R.; Haroon, S.; Ahmed, H.H.; Das, J.K.; A Bhutta, Z. Impact of community-based interventions on HIV knowledge, attitudes, and transmission. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2014, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakha, M.A.; Kazerooni, P.A.; Lari, M.A.; Sayadi, M.; Azar FE, F.; Motazedian, N. Effect of an educational intervention on knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviours related to HIV and sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in southern Iran: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. STD AIDS 2013, 24, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, N.; Amudha, R.; Vasuki, S. Pre- and post-HIV test knowledge, attitude, behavior, and practice of people living with HIV and AIDS by questionnaire pattern. Indian J. Sex Transm. Dis. AIDS 2020, 41, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazete, C.; Caveiro, D.; Neto, M.L.; Dinis, J.P.; Rocha, L.C.; Sa, L.; Carvalhido, R. Validation of a Questionnaire on Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Immigrant Vocational Education Students in Portugal from Sao Tome and Principe. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Iryani, B.; Basaleem, H.; Al-Sakkaf, K.; Crutzen, R.; Kok, G.; Borne, B.v.D. Evaluation of a school-based HIV prevention intervention among Yemeni adolescents. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, T.; Ali, A.; Worku, A. Effects of peer education intervention on HIV/AIDS related sexual behaviors of secondary school students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A quasi-experimental study. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention program.

Table 1.

Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention program.

| Program session |

School-based HIV prevention activities |

Goals |

Multidisciplinary |

| Group Dynamics |

|

|

Researcher + research assistant teacher |

| Gender equality |

|

Exploring student view of gender equality, and characteristic of men and women Students understand the different between men and women characteristics |

Researcher + teacher |

| Reproductive health |

Discuss about reproductive health and how to keep the reproductive hygiene Explain the reproductive organ using the phantom Sharing with student regarding puberty concept and organ function during puberty period Sharing on physical and psychological changes during puberty period |

|

Researcher + teacher |

| Goal setting and problem solving |

|

|

Researcher + teacher |

| Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexual Violence |

|

|

Researcher + teacher+ Research assistant |

| Positive communication and decision-making skill |

Positive communication and empowering of students from parents, teacher, and community Emotional support from parents, teacher, and community |

|

Researcher + teacher+ Research assistant+ parents |

| Reproductive Health Services |

|

|

Researcher + teacher |

Table 2.

Mean difference of knowledge, subjective norm and attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among intervention groups before and after receiving Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention.

Table 2.

Mean difference of knowledge, subjective norm and attitude, and behavior control of reproductive health and HIV prevention among intervention groups before and after receiving Sexual Reproductive Health School – Based HIV Prevention.

| Variable |

Papua Districts |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

t |

df |

p-value |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|

|

|

| Knowledge on reproductive health and HIV prevention |

Manokwari |

3.1546 |

0.38271 |

3.0235 |

0.42542 |

2.331 |

48 |

0.024 |

| Fak- Fak |

3.0984 |

0.41614 |

3.1762 |

0.40777 |

-22.766 |

46 |

0.000 |

| Sorong |

3.0602 |

0.33271 |

2.9185 |

0.45545 |

2.183 |

37 |

0.035 |

| Subjective norm and attitude reproductive health and HIV prevention |

Manokwari |

2.5065 |

0.39162 |

2.6766 |

0.33244 |

-3.175 |

48 |

0.003 |

| Fak- Fak |

2.8398 |

0.47992 |

2.8650 |

0.48009 |

-12.906 |

46 |

0.000 |

| Sorong |

2.5695 |

0.30393 |

2.7319 |

0.49697 |

-2.002 |

37 |

0.053 |

| Behavior control on sexual transmitted and HIV prevention |

Manokwari |

2.8637 |

0.33062 |

3.0510 |

0.34295 |

-5.102 |

48 |

0.000 |

| Fak- Fak |

3.0194 |

0.33062 |

3.1128 |

0.30953 |

-2.517 |

46 |

0.001 |

| |

Sorong |

2.8178 |

0.34611 |

3.0856 |

0.51060 |

-3.685 |

37 |

0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).