1. Introduction

Laparoscopic surgeries have become increasingly common for various medical conditions in teenagers. While these minimally invasive procedures offer numerous advantages, the experience of pain after surgery remains a significant concern. Adolescence is a time of physical transformation, continued cognitive and psychological growth, and the transition from childhood to adulthood. Assessment of teenagers with postoperative pain is a challenging aspect of pediatric care. Numerous factors, including individual pain thresholds, previous experiences with pain, anxiety levels, and support systems, influence teenagers' pain perception. There is an anecdotal and clinical impression that teenage patients sometimes report exaggerated postoperative pain scores that do not correlate with the actual level of pain. Pain is whatever the teenagers say it is and exists whenever they say it does. Even if our subjective perception of the reported pain is different, and an accurate explanation of presumed exaggerated pain scores is missing, we do not want our patients to be in pain and suffer. The consequences of untreated pain can be devastating to patients, resulting in behavior problems and setting the stage for future experiences of pain [

1].

Conversely, treatment of postoperative pain can contribute to sustained opioid use and misuse. Exploring what may drive our belief that teenage patients do not always accurately self-report pain is complex and is unlikely to be solely a perception problem. We need to explore the pain perception of caregivers (parent and nurse), the pain behavior, and psychological factors of teenagers that can influence self-reported pain.

Patient self-reporting of pain is the rule in clinical practice [

2]. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is a well-established tool for assessing children's postoperative pain and is strongly recommended for self-reporting acute pain [

3]. This scale may underestimate or overestimate actual pain, and developing a paradigm of the correlation between patient-parent, patient-nurse pain scores, pain scores-pain behavioral observation, and pain scores and physiological parameters can help us better understand teenager self-reported pain.

The patient-parent and patient-nurse relationships are significant in the postoperative period. The parents and children are very interconnected [

4,

5]. The child's expression of pain can cause parents distress, and the parents often serve as secondary reporters of the children's pain, which may have unintended consequences. Although professionals may underestimate patients' pain [

6], the nurse's input can impact pain treatment in challenging situations. However, the reliability of these dyads (teenager-parent, teenager-nurse) in assessing postoperative pain has not been conclusively determined in this teenage population.

Adolescence is a developmental period when communication about health problems can be difficult. Pain expressions provide meaningful information about teens' responses to pain, and parents and nurses can use the patient's pain behavior to assess the adolescent's pain [

7]. Unfortunately, there is no consensus regarding the agreement between pain behavior and self-reported pain intensity. Still, consideration of this measure can contribute to the complex situation of judging teenagers' postoperative pain.

The self-reported pain should be complemented not only by the pain behavior but also by knowledge of the anxiety level, catastrophizing attention to pain, and mood. The patient's anxiety correlates with the severity of pain [

8,

9,

10]. Nevertheless, the existing studies did not investigate the relationship between stress and acute postoperative pain in teen patients, and evaluation of trait anxiety can be part of this comprehensive assessment battery. The catastrophic thinking about one's pain is related to increased attention to pain [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. All teenagers experience various moods and mood swings during their teenage years. In the postoperative period, an adolescent patient can feel happy and excited one minute, upset and scared in the next minute. However, the relationship between teenager's mood and postoperative pain has not been well examined.

This study aimed to (1) determine the parent and nurse level of agreement with teenager pain scores; (2) correlate the reported pain scores with teenager pain behavior scores as reported by the parent and nurse; and (3) identify psychosocial factors that may contribute to teenager pain perception (anxiety, catastrophizing thoughts and mood). Overall, this study seeks to answer the question: Do nurse and parent reporting of a teenager's postoperative pain scores, in addition to knowledge of patient pain behavior, pain catastrophizing thoughts, anxiety, and mood level, help the medical provider to gauge whether a teenage patient's self-reported pain score accurately reflects the patient's experience of pain?

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was conducted at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (CHP) between December 2012 and August 2014 and was approved by The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. The study was registered at

www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 017555065) in December 2012. The participants were recruited from CHP and were selected based on a review of medical records and a medical interview with the patient and parent on the day of surgery.

Two thousand two hundred forty-one (2,241) patients at CHP underwent laparoscopic procedures, including robotic cholecystectomies, between December 20, 2012, and August 13, 2014. Nine hundred fifty-nine patients were excluded because of the nature of their procedure (e.g., orchiopexy, Nissen fundoplication, hernia repair, etc.); 623 patients were excluded for being outside of the target age range; 78 patients were excluded because the study team was unavailable to screen and consent patients; and 351 did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria upon medical record review.

Of the 230 patients approached for the study, six did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria, three patients or parents refused to participate, two did not fully complete consent (one started crying, the other fell asleep for surgery), six patients were discharged before questionnaires were completed, three parents were unavailable on postoperative day( POD ) 1, two parents withdrew consent POD 1, and three procedures were converted to open procedures. Three patient/parent/nurse units did not complete all study assessments. Two hundred two patients (202) (along with their parents and nurses) completed all study procedures (

Figure S1).

Patient inclusion criteria were: 1) age between 11 and 17 years old, 2) scheduled for elective or emergent laparoscopic surgeries, and 3) overnight admission. Exclusion criteria included chronic pain conditions (pain of more than three months), non-English-speaking family, history of cognitive impairment, developmental delay, and psychiatric medical history (except attention deficit disorders such as ADD and ADHD). Patients were also excluded for positive pregnancy tests, taking drugs (including marijuana and other recreational drugs), being medicated at home or in hospital with long-acting opioids (methadone, oxycontin, oxymorphone E.R., morphine slow release) or clonidine, antipsychotic, antidepressant, and anxiolytic medications. Patients who experienced surgical, anesthesia, or medical complications, were discharged on the day of surgery, and had laparoscopic surgeries converted to open were excluded. Those patients with no parent available to complete the questionnaires were also excluded.

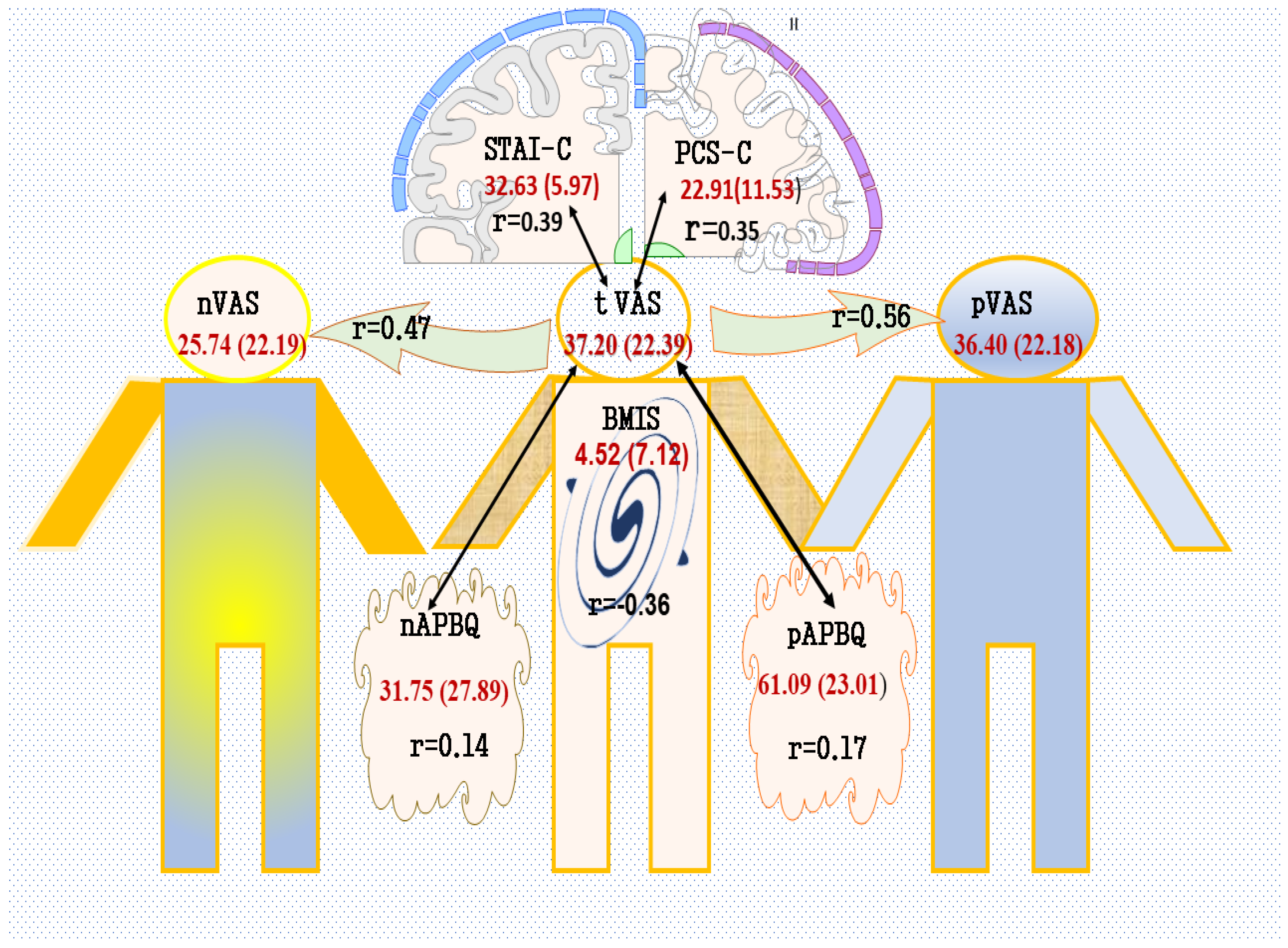

The principal investigator or one of the co-investigators obtained informed consent on the day of surgery before the surgery was performed. Patient demographic information was collected from medical records (age, gender), a medical interview at enrollment, and POD 1 (race, ethnicity). The patient's pain scores were documented using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scale and the pain behavior using the Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire (APBQ). Anxiety was recorded using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children questionnaires (STAIC S – Anxiety); catastrophic thoughts were documented using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Children (PCS-C); and the teenager's mood level was recorded using the Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS).

The research assistant visited all patients on day one after surgery and met the patient, the parent, and the nurse. All participants were blinded from other assessed scores. The teenager completed a VAS questionnaire (VAS teen) and three psychological questionnaires (STAIC-S, PCS-C, BMIS). One of the family members (preferably the mother) completed the Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire (pAPBQ) and VAS questionnaire (pVAS). The patient's nurse completed the same questionnaires as the family member, nAPBQ and nVAS. All the questionnaires were conducted at the same time.

Questionnaires:

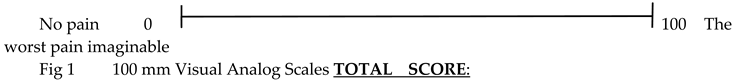

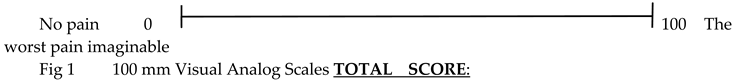

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

The VAS is a horizontal 100 mm line. At the ends of this line, there are two labels: "no pain" and "the worst pain imaginable" (100mm on the scale). Patients marked the line representing their level of pain. The nurse and the parent also completed a VAS, each rating their perception of the teenager's pain intensity.

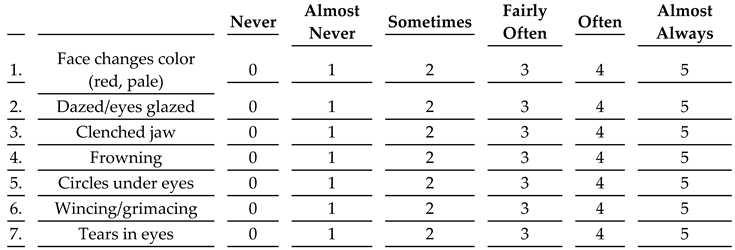

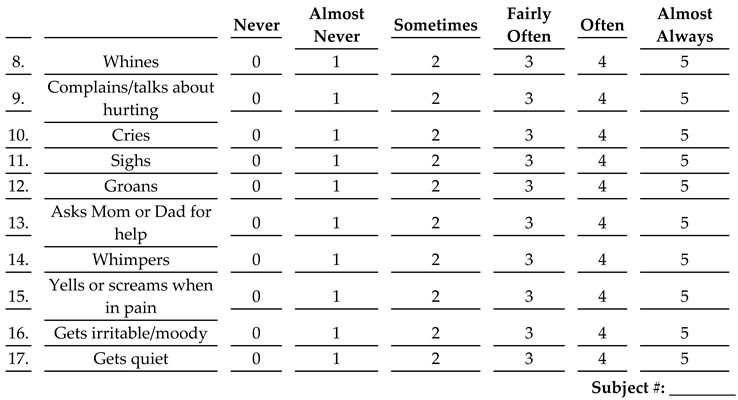

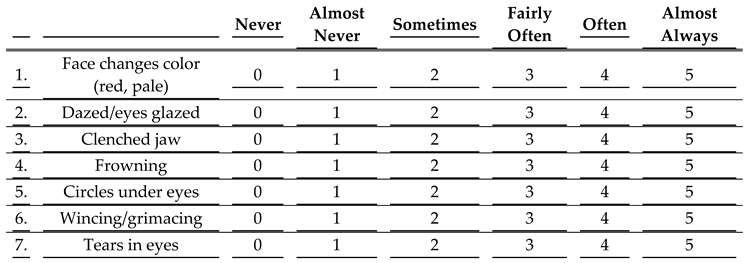

Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire (APBQ)

This is a parent-report measure of adolescent (11–19 years) pain expressions [

7]. It contains 23 items with high internal consistency (alpha = 0.93). The parent rates the child on each pain behavior from 0 (never) to 5 (almost always), and the total score ranges from 0 to 115 [

7]. Lynch-Jordan et al. provided preliminary reliability and validity results after testing it on 138 parent-adolescent dyads[

7].

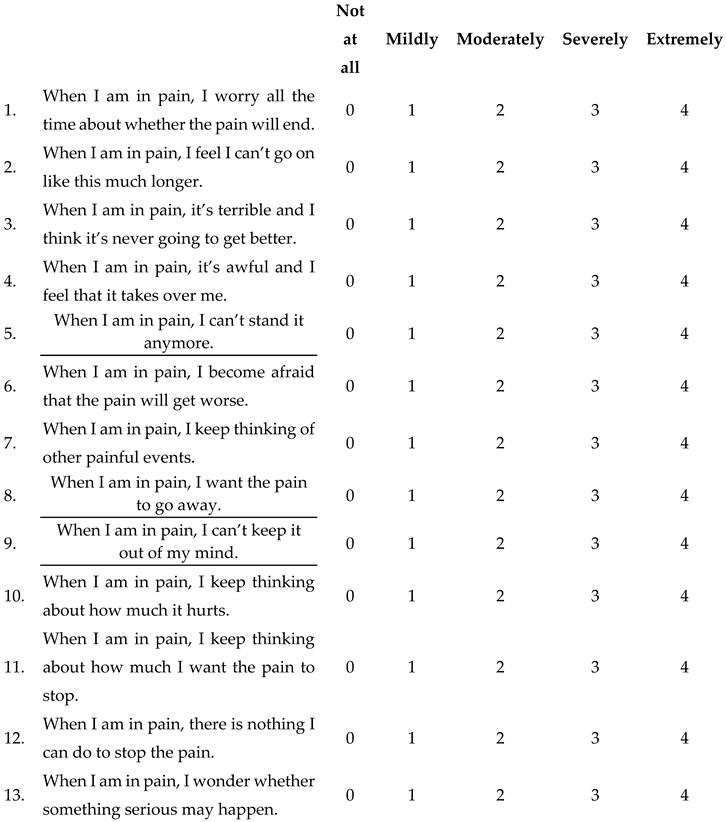

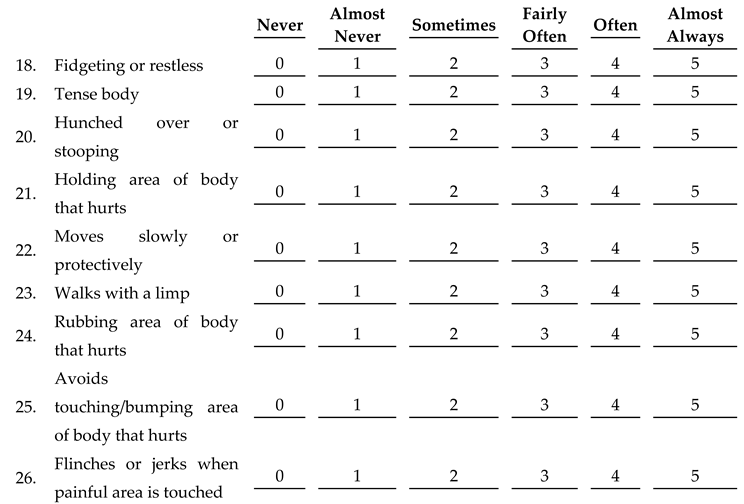

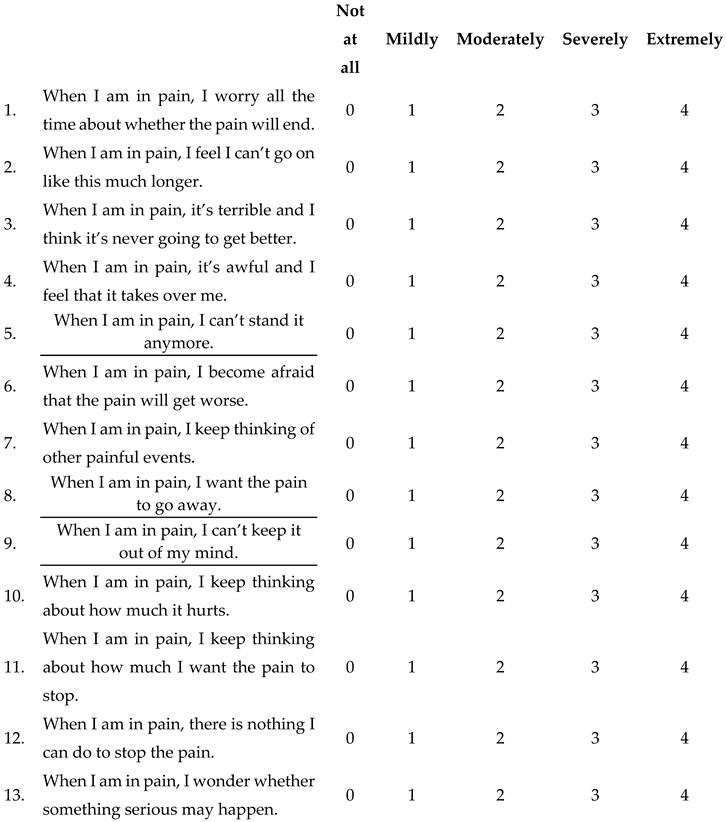

Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Children (PCS-C) [16]

The PCS-C is a 13-item questionnaire that is an adaptation of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale for use in adults. The scale was adapted by rewording one item (i.e.), simplifying the rating scale and repeating the item stem at the beginning of each item ("When I am in pain…")[

16]. The children rate how frequently they experience each of the thoughts and feelings when they are in pain using a five-point scale (0 = "not at all"; 4 = "extremely"). The PCS-C consists of three subscales: (1) rumination (e.g., "... I keep thinking about how much it hurts."); (2) magnification (e.g., "... I wonder whether something serious might happen."); and (3) helplessness (e.g., "... there is nothing I can do to reduce the pain."). There is evidence of construct and predictive validity [

16]. The PCS-C yields a total score ranging from 0 to 52 and three subscale scores for rumination, magnification, and helplessness. The scale evidenced excellent reliability with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92; alphas for the subscales ranged from 0.68 to 0.88 in the current sample.

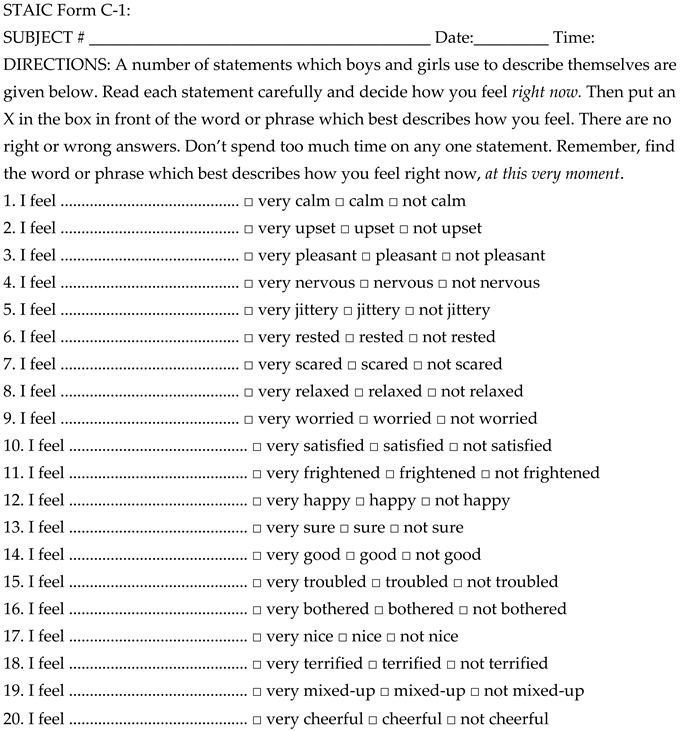

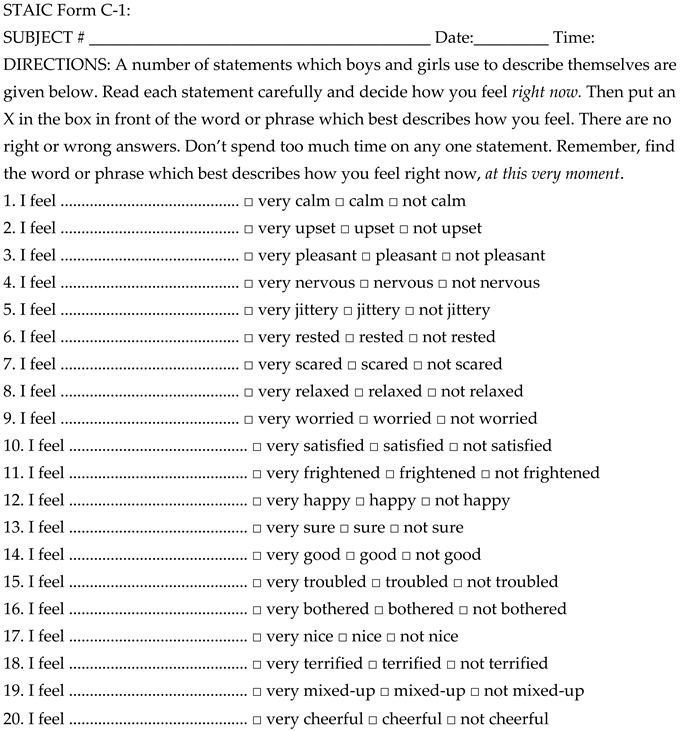

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC S – Anxiety) [

17]

Participants completed the state version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children to measure teenager anxiety on POD 1. The STAIC S-Anxiety scale consists of 20 statements that ask the teenagers how they feel at that particular moment (e.g., "I feel…") by checking one of the three alternatives that describe the child best (e.g., "very calm," "calm," or "not calm"). The total score for this scale ranges from 20-60. The alpha reliability of the STAIC S-Anxiety scale was 0.90 in the current study.

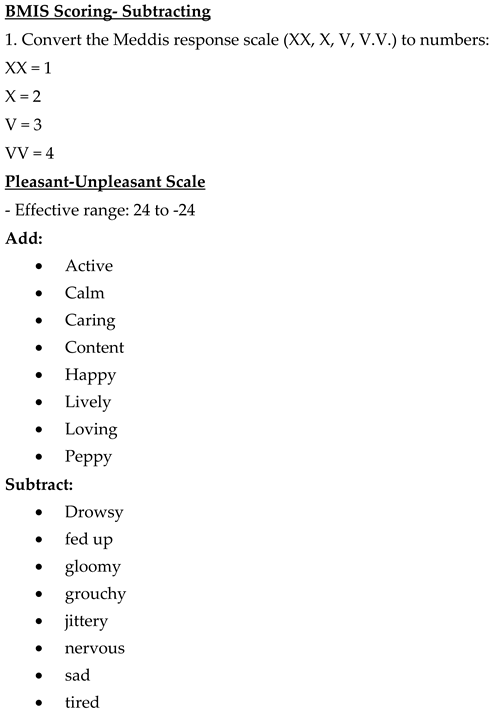

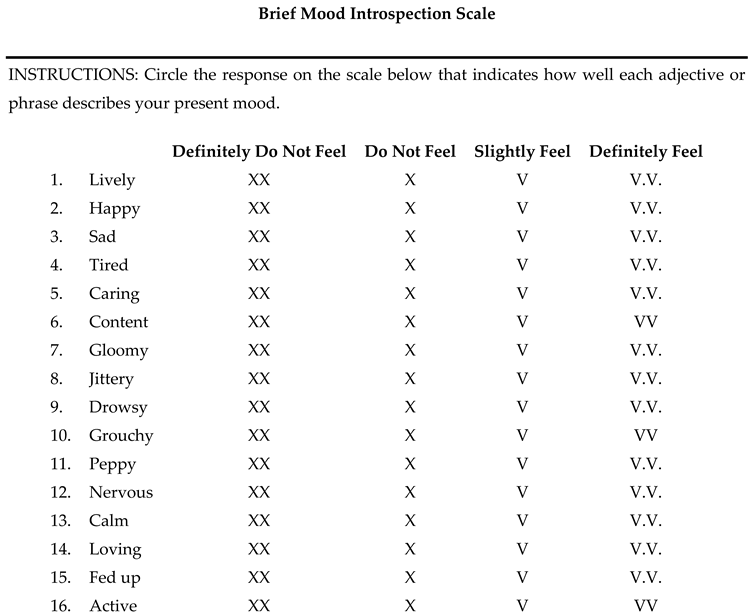

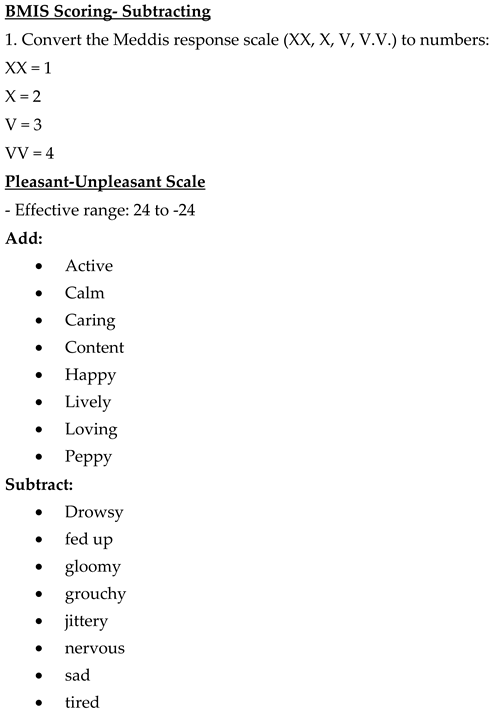

Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS)

The Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS) is a mood adjective scale with 16 adjectives, two selected from each of eight mood states (happy, loving, calm, energetic, anxious, angry, tired, and sad) [

18]. Participants were asked to indicate how well each adjective described their present mood using a 4-point scale from 1 ("definitely do not feel") to 4 ("definitely feel"). Positive adjectives were added, while negative adjectives were subtracted for a total score ranging from -24 to +24. The scale evidenced moderate reliability (Cronbach's alpha 0.83) for the current study.

Statistical Analyses

The basic descriptive statistics (including means, medians, and standard deviations) were used to describe the measurements. Boxplots, scatter plots, and q-q plots examined the distributional assumptions for all variables of interest. The proposed analysis involved the computation of Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficient between the VAS pain scores for teenagers with each of the VAS pain scores for the parent and nurse, between the VAS pain scores for teenagers and pain behavior scores reported by the nurse and family, and between VAS pain scores and the psychosocial factors. The correlations were considered weak if values were 0.23 to < 0.30, moderate if 0.30 to < 0.50, and high if ≥0.50.

Sample Size and Power: For a small correlation of 0.23, a sample size of 206 was required to achieve 80% power using a two-sided hypothesis test with a significance level of 0.0125 (Bonferroni correction for all four comparisons, 0.05/4 = 0.0125). Anticipating that the sample size is 206 with three observations (i.e., teenager, parent, and nurse), the study was powered (80%) to detect an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.10 using an F-test with a significance level of 0.05. To determine inter-rater reliability between two observations (e.g., teenager versus parent), the study achieves 80% power to detect an intraclass correlation of 0.19 using an F-test with a significance level of 0.025 to account for multiple comparisons. Outcome measure scores and Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated using SAS software Version 9.3 of the SAS System for Windows. Copyright ©2002-2010 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

4. Discussion

In line with previous research, we noticed that pain assessment and management are complex in teenage patients and pose significant challenges for healthcare providers[

19]. There is an increased focus on excellent postoperative pain control, and it is a common practice for medical providers to administer opioid medication to a teenager who reports a numeric pain score ( NRS) of 4 or more. Frequently, we perceive that the teens have reported exaggerated pain scores, and we need to understand the self-reported pain scores better and verify their credibility.

Different self-reported pain scales assess postoperative pain (NRS, VAS, verbal rating scale -VRS). The VAS is frequently used and has good reliability, validity, responsiveness, acceptability, low costs, and metric measures [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. It is an appropriate scale for children eight years of age and older [

25]. Statistically, the VAS is more robust and sensitive to change than other self-reported scales [

20,

23]. However, it is difficult for some subjects to transform a subjective sensation representing pain intensity into a mark on a straight line. It can be exaggerated, minimized, or unrealistic [

26,

27]. In addition, the VAS pain scores represent an incomplete representation of the pain experience. Other factors can be investigated to understand the multidimensional aspect of postoperative pain. Huguet et al. suggested that self-reported pain should be complemented by observation and knowledge of the context [

28]. This approach can be very beneficial when determining the credibility of self-reported pain is essential.

Children and teenagers are dependent upon care from their parents, and the parents carry the responsibility of their postoperative care, and their pain scores can be interconnected[4.5]. A parent familiar with the child's normal behavior will be able to identify pain-related behaviors, and the nurse's knowledge can impact the child's pain treatment. van Dijk et al. reported that the VAS pain scores reported by a pediatric patient have a variable correlation (0.23-0.85) with pain scores reported by different caregivers (parent, nurse, researcher, physician [

29]. van Dijk and Khin Hla et al. found that children ( 3-11 years) and parents agree about pain scores ( r=0.113) [

29,

30]. However, these results cannot be extrapolated to teenage patients, but we found that teenagers and parents (r=0.56) have a high level of agreement on pain scores.

Controversies exist about the level of agreement between patients and healthcare providers. Seers et al. recommended stopping doing any studies comparing such pain scores because professionals underestimate patients' pain[

6]. Seers et al. and Khin Hla et al. found a tendency for nurses to report lower scores[ 0 ( 0-2)] than parents [ 2 (1-4)] and pediatric patients ( 2 ( 0-4)][

6,

30]. Despite these findings, we feel that the pediatric studies are inconclusive about the ability of healthcare providers to perceive postoperative pain. The magnitude of the underestimate depends on the patient's severity of pain and needs to be investigated more. The healthcare provider's opinion is essential for appropriate pain treatment. The nurses can have views that are very different from patients, and their pain scores are influenced by the medical knowledge about the amount of tissue damage during surgery, vitals, the relation with the child and family, the time spent with the child, training Seers [

6], experience, and patient likability[

31]. While confirming that the nurses reported lower mild pain scores than the patients, our study showed the nurses agreed with the parents and the teenagers. In addition, the underestimation is slight (25.5±22.1 vs 37.0 ± 22.3) and most likely would not contribute to undertreatment of pain.

It is unclear what type of pain behavior is most suitable for assessing teenagers' postoperative pain control. Pain behavior can be verbal or non-verbal, including subjective perception of patient facial expressions, body position, gestures, activity level, and breathing pattern[

32,

33]. It is under conscious or unconscious control [

34]. It is our observation and other researchers that many teenage patients with postoperative pain report very high pain scores but are relaxed, playing games, or texting friends, indicating no pain at all [

33]. Our literature research revealed only a few small pediatric studies comparing self-reported VAS pain scores with pain behavior. The investigated pain behavior varies from study to study. In a meta-analysis of 29 studies (82% adult study contribution), significant variability exists between the studies, with a moderately positive association (z = 0.26) [

35]. This relation is more likely to be substantial when the individual being studied has acute pain (z =0.35) and when the self-report of pain intensity data is collected soon after the observation of pain behavior (z = 0.40) [

35].

A 23-item pain behavior questionnaire, APBQ, was used to assess chronic pain in teenage patients[

7]. In 138 parent-adolescent (11-19 years) dyads, no relationship was found between parent-reported pain behaviors and adolescent-reported chronic pain intensity [

7]. Still, a small but significant correlation was found between parent estimates of their adolescent's pain intensity and parent reports of pain behaviors (r = 0.25). The APBQ was not tested for teenagers with acute postoperative pain, but we feel that this questionnaire was more suitable for our patient population than other pain behavior scales used. It is essential to mention that, in contrast with the study done by Lynch-Jordan[

7], we found a very weak but significant correlation between reported teen pain scores and parent pain behavior (r= 0.16). These results can partially explain our observations that the teenager's pain behavior does not always correlate well with the magnitude of the reported pain score.

Also, we want to mention that the association between nurse pain scores and teen pain behavior was minimal, and "behavior," as a subscale of APBQ, was not a significant teen pain score predictor when parents completed the APBQ. Trying to understand why the correlation between the nurse/parent pain scores and teenager pain behavior is so weak is difficult. During our study, the pain scales were completed independently, and the nurse and parent were aware of the child's pain behavior but unaware of the child's rating. However, during the hospital stay, the nurse and parent frequently assessed the child's pain, and we felt that the nurse and parent couldn't separate their perception of the child's pain behavior from what the child was telling them ( pain scores reported before questionnaires completion).

Teen patients can have a variable impression of their subjective postoperative pain, poor psychological adjustment to acute postoperative pain (increased anxiety level and catastrophizing attention to pain), and their moods can affect the reported pain scores. This study, while essentially confirming expected correlations between pain scores and psychological factors and psychological interventions, may be effective in managing and reducing postoperative pain [

36]. Higher levels of depressive symptoms and more significant pain catastrophizing thoughts reported by teenagers with chronic pain correlated significantly with parent-reported teenage pain behavior [

7], and we found similar results for catastrophizing pain in teenagers with postoperative acute pain. This is the first study that investigated a relationship between mood and postoperative pain. In the postoperative period, a teenage patient can feel happy and excited one minute, upset and scared in the next minute. This study finds a moderate negative correlation between mood and pain.

There are some limitations to this study.

First, the reported mean pain was mild (37.0 ± 22.3), and our study did not focus on teenagers in severe "unreal" pain. Unfortunately, our raised research question was left unanswered. We feel that conducting a study that includes only such patients is not practical and ethical. Despite this limitation, this study highlights a few modalities to assess pain in ambiguous and confusing situations.

Second, teenagers' psychological flexibility can impact psychological measurements the day after surgery. Unfortunately, we did not have any baseline psychosocial factor measurements for this study. However, it is unclear if available psychological baseline measurements will change our results.

Third, we present correlational values between different parameters, but we cannot recommend how to use our findings to guide opioid dosing in the postoperative period. Also, we feel that pain behavior can be very misleading in judging postoperative pain. In a challenging situation, the absence of signs of pain behavior cannot guarantee that the patient has no pain.

Fourth, we asked the mothers to complete the questionnaires, as mothers are often considered the primary caregivers. This can be a source of bias as we are aware that the mother's responses to child pain may differ from those of fathers [

36,

37,

38]. However, previous studies reported that the mothers and fathers did not significantly differ in their levels of catastrophizing and trait anxiety [

37,

39]. In our study, mothers, not fathers, were primarily available for the studies.

Finally, our results apply to teenagers presenting with mild-moderate postsurgical pain and may not be appropriate to generalize to more painful surgical procedures.

Unanswered questions and future research.

Teenagers often feel hopeless, and we do not want to dismiss their reported pain scores. In challenging situations, it is crucial to identify potential sources of pain, both surgical and non-pain-related distress, and take appropriate actions. This study, while confirming expectations about the level of agreement between patients and multiple providers, and pain scores and psychosocial factors, can serve as an essential basis for future research. Outlining a risk stratification algorithm that may identify strategies to downgrade the severity of pain to a lower one and decrease the need for postoperative opioid administration is only a start. Several observations can be considered necessary when assessing a patient with severe pain that a healthcare provider perceives as being exaggerated and unreal: 1) parent-proxy pain scores – they may underestimate teen pain scores (i.e., patient-severe but parent-moderate); 2) nurse proxy pain scores-they may underestimate teen pain scores ( i.e., patient-severe but nurse- mild) 3) the pain behavior- the teen has a relaxed body, moves with ease, has no verbal complaints of the pain, stable vitals, and enjoys video games -suggestive of low pain severity; 4) the anxiety level- the teen feels calm, pleasant, cheerful, relaxed, happy, satisfied, suggestive of low anxiety level, 5) the teen catastrophizing thoughts- a patient that does not worry, not afraid of pain, suggestive of low catastrophizing thoughts or feelings; 6 ) the patient mood- a lively, happy, caring, calm, content, loving, active teenager can suggest a good mood. In addition, using appropriate questionnaires to identify psychological distress can be considered an objective way of assessing pain and psychological factors in such situations. Still, more studies are needed to investigate if implementing these strategies postoperatively is practical and improves satisfaction with pain control.

Appendix A

The questionnaires and the score documents used: Visual Analog Scale from the teenager (tVAS ), Visual Analog Scale from the parent (pVAS ), Visual Analog Scale from the nurse (nVAS ), Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire from the parent (pAPBQ), Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire from the nurse (nAPBQ), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for the children (STAIC S – Anxiety), Pain Catastrophizing Scale for the children (PCS-C), and Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS).

Pain Questionnaire - Patient

How severe is your pain now?

Place a vertical mark on the line below to show how much pain you are feeling right now.

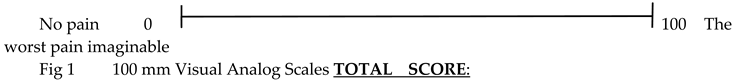

Pain Questionnaire - Parent

How severe do you think your child’s pain is right now?

Place a vertical mark on the line below to indicate how much pain your child is feeling right now.

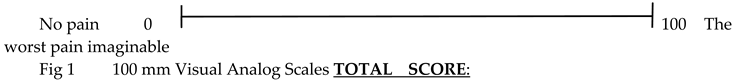

Pain Questionnaire - Nurse

How severe do you think your patient’s pain is right now?

Place a vertical mark on the line below to indicate how much pain your patient is feeling right now.

Subject #: ________

Date: ___ ____________ _______

Time: __ __:__ __

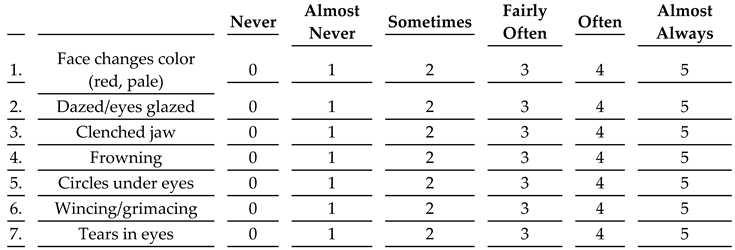

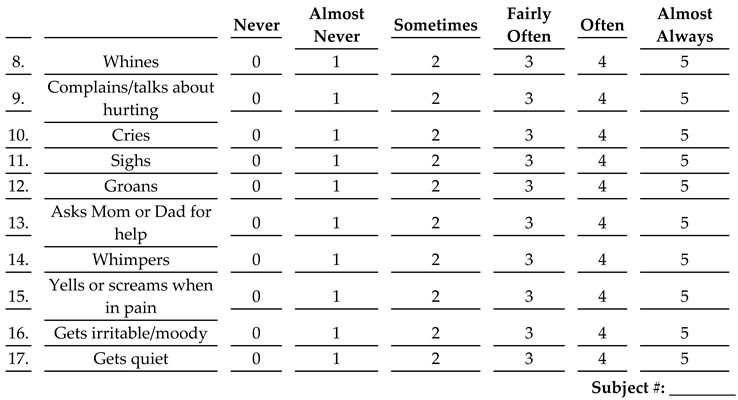

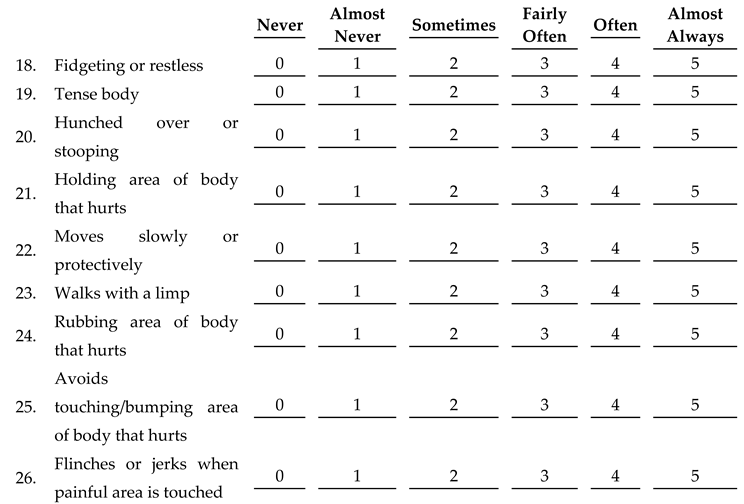

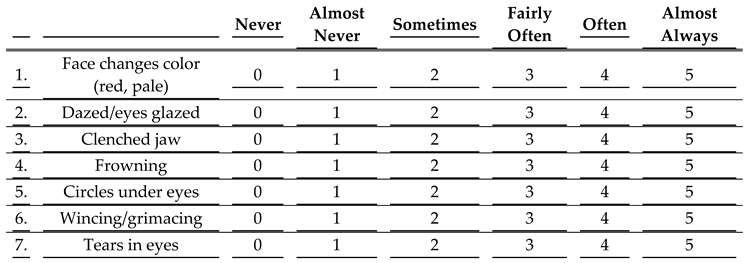

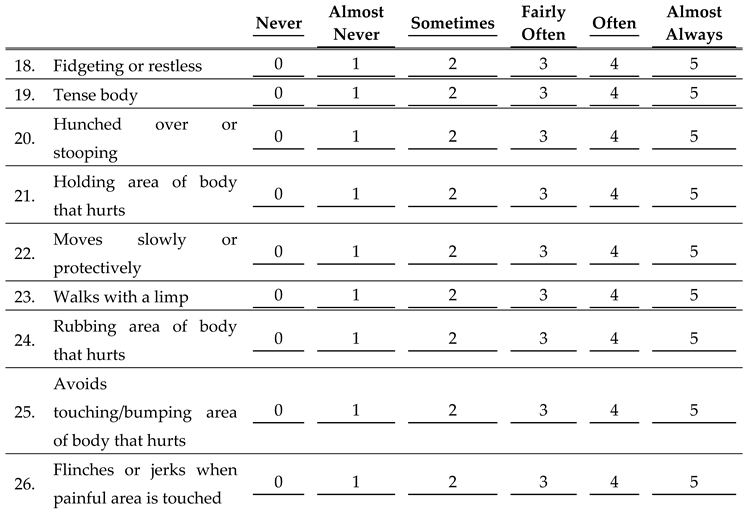

Adolescent Pain Behaviors Questionnaire- Parent

Below is a list of common ways that children and teenagers use their faces to express when they are in pain. Please rate each behavior from 0 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) to show how often you notice your child making these facial responses when he/she is experiencing pain.

Below is a list of common things that children and teenagers may say or do when they are in pain. Please rate each behavior from 0 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) to show how often you notice your child making these sounds or asking these questions when he/she is experiencing pain.

Below is a list of things that children and teenagers may do when they are in pain. Please rate the behaviors from 0 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) to show how often you notice your child making these actions and gestures when he/she is experiencing pain.

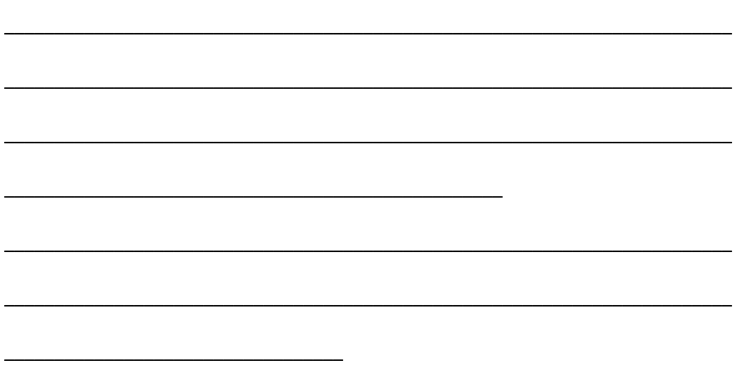

Other comments regarding your child’s behavior:

TOTAL SCORE:

This questionnaire was adapted from the Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire described in the 2010 article from the PAIN journal Vol. 151, 834-842, “Parent perceptions of adolescent pain expression: The adolescent pain behavior questionnaire,” by A.M. Lynch-Jordan, S. Kashikar-Zuck, and K.R. Goldschneider.

Adolescent Pain Behaviors Questionnaire- Nurse

Below is a list of common ways that children and teenagers use their faces to express when they are in pain. Please rate each behavior from 0 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) to show how often you notice your patient making these facial responses when he/she is experiencing pain.

Below is a list of common things that children and teenagers may say or do when they are in pain. Please rate each behavior from 0 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) to show how often you notice your patient making these sounds or asking these questions when he/she is experiencing pain.

Below is a list of things that children and teenagers may do when they are in pain. Please rate the behaviors from 0 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) to show how often you notice your patient making these actions and gestures when he/she is experiencing pain.

Other comments regarding your patient’s behavior:

TOTAL SCORE:

This questionnaire was adapted from the Adolescent Pain Behavior Questionnaire described in the 2010 article from the PAIN journal Vol. 151, 834-842, “Parent perceptions of adolescent pain expression: The adolescent pain behavior questionnaire,” by A.M. Lynch-Jordan, S. Kashikar-Zuck, and K.R. Goldschneider.

HOW-I-FEEL QUESTIONNAIRE sample

Developed by C.D. Spielberger, C.D. Edwards, J. Montuori, and R. Lushene

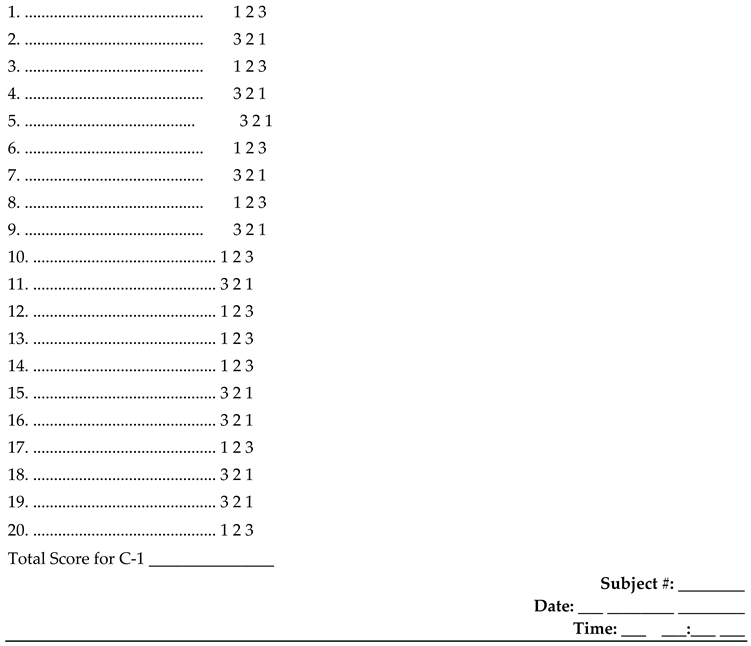

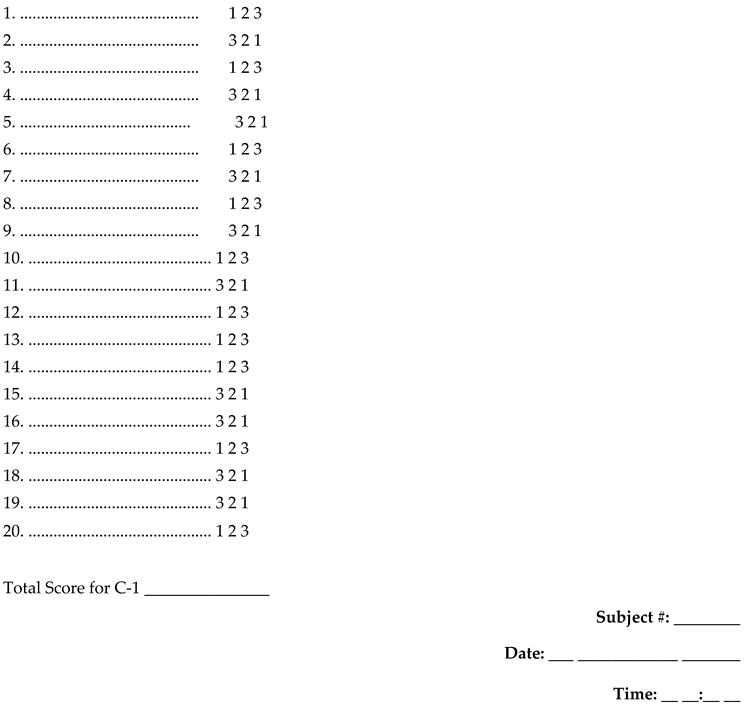

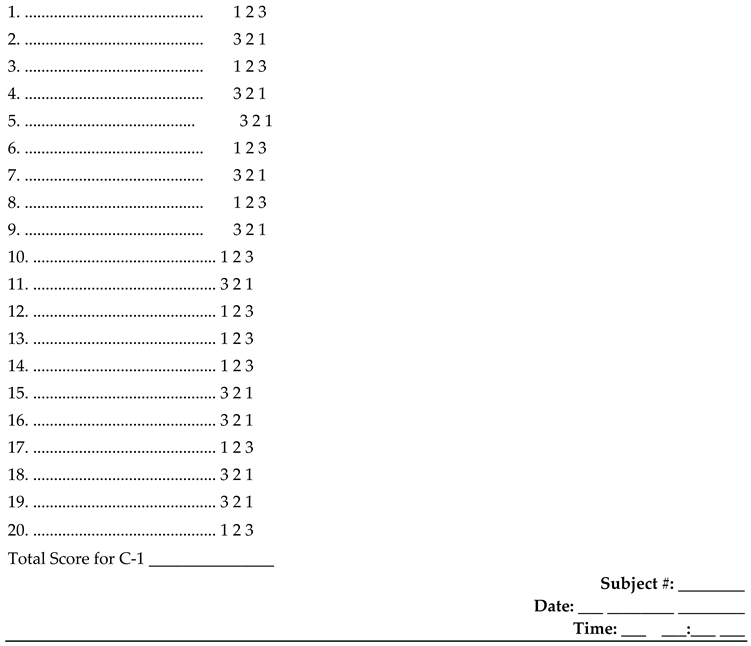

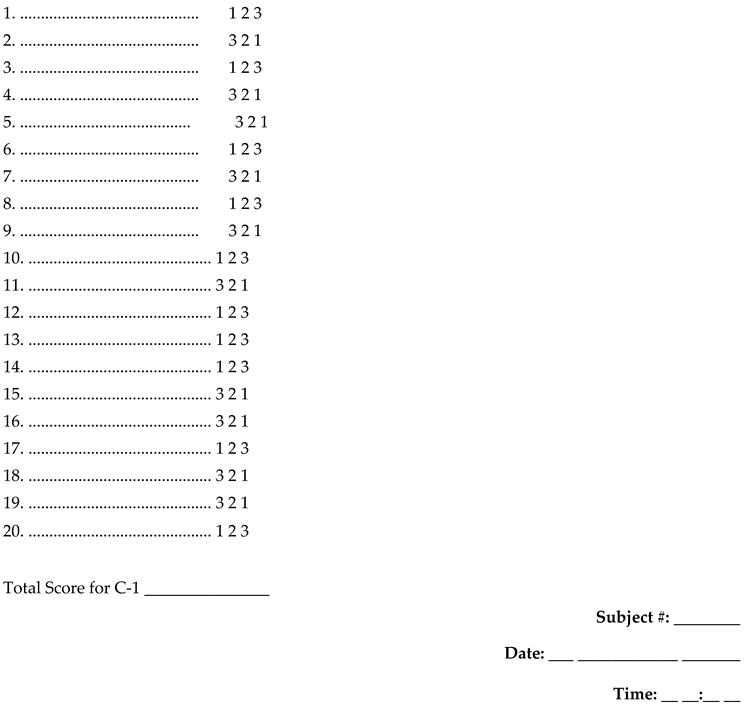

Scoring Key for STAI for Children Sample

Scoring Instructions for STAIC Form C-1

Fold this paper in half and line up next to the appropriate item numbers on the answer sheet.

Be sure you are on the correct side of the answer sheet (Form C-1). Total the scoring weights shown for the marked responses.

Thoughts and Feelings During Pain (PCS-C)

We are interested in what you think and how strong the feelings are when you are in pain. Below are 13 different thoughts and feelings you may have when you are in pain. On a scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely), try to show us as clearly as possible what you think and feel by putting a circle around the word that best reflects how strongly you have each thought, after each sentence.

TOTAL SCORE:

This questionnaire was adapted from the pain catastrophizing scale for children (PCS-C) described in the 2003 publication in the PAIN journal, Vol. 104, 639-646, “The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): a preliminary validation,” by G. Crombez, P. Bijttebier, C. Eccleston, T. Mascagni, G. Mertens, L. Goubert, K. Verstraeten.

Scoring Key for STAI for Children Sample

Scoring Instructions for STAIC Form C-1

Fold this paper in half and line up next to the appropriate item numbers on the answer sheet.

Be sure you are on the correct side of the answer sheet (Form C-1). Total the scoring weights shown for the marked responses.

TOTAL SCORE:

This questionnaire was adapted from the Brief Introspection Scale (BMIS) published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, Vol. 55, No1, 102-111, “The Experience and Meta-Experience of Mood,” by J.D. Mayer and Y.N. Geschke.