1. Introduction

Individuals with thromboembolic disease, prosthetic valves, or coagulation issues are frequently prescribed anticoagulants and/or antiaggregants. Managing patients undergoing anticoagulation, poses a unique challenge in dental procedures due to the heightened susceptibility to prolonged bleeding [

1]. Oral hygiene procedures on a non-coagulated patient can cause bleeding which can worry both the patient and the operator, especially in the case of procedures such as scaling and root planning.

The probability of experiencing bleeding complications is influenced by the type of anticoagulant and by drug dosage. Over time, two primary types of blood thinners have been commonly employed: antiplatelet medications, such as acetylsalicylic acid, and classical anticoagulants such as warfarin (VKA: vitamin K antagonists). Each of these drugs operates through distinct mechanisms, affecting the coagulation cascade in their unique ways. While acetylsalicylic acid primarily inhibits platelet aggregation, warfarin exerts its anticoagulant effects by interfering with the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors.

It is crucial for healthcare providers to carefully consider the patient's medical history, underlying conditions, and lifestyle factors when selecting an anticoagulant/antiaggregant therapy. A personalized approach helps optimizing the balance between preventing thrombosis and minimizing the risk of bleeding complications. As medical knowledge continues to evolve, ongoing research may reveal even more tailored and effective anticoagulation strategies.

Routine dental procedures or simple tooth extractions generally do not carry a significant risk of bleeding when the international normalized ratio (INR) is <2.5 [

2,

3]. However, there is limited information regarding the combined use of these medications or the utilization of newer anticoagulants [

4] .

Since their introduction in 2010, new oral anticoagulants (NAO) such as DTI: direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) AntiXa: directa factor Xa inhibitors (endoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) have gained popularity, especially among older adults, for their advantages over VKA, such as a shorter half-life and the absence of a need for laboratory testing. These newer agents offer a promising alternative to traditional options, often providing more predictable and efficient anticoagulation with fewer dietary restrictions. Two major studies, the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RELY) and Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE), have indicated that the rates of postoperative bleeding following dental procedures are comparable between patients taking warfarin and those taking NAO [

5,

6].

A retrospective study by Rubino et al. [

4] indicated a minimal occurrence of postoperative bleeding events in individuals undergoing invasive periodontal procedures, irrespective of whether they were on antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications, maintained or discontinued the medication, had a medical comorbidity, or were smokers. Additionally, the study highlighted the need for additional research specifically examining the use of NAO.

Ivy was the first author to propose a test to evaluate bleeding time. In this method the patient's arm is positioned at heart level, and a blood pressure cuff is inflated to 40 mmHg. Following alcohol cleansing, a standardized device is used to create a 10 mm long and 1 mm deep incision on the volar forearm. A timer is employed to blot the blood twice a minute, and the timer is stopped when there is no further bleeding after blotting. Time greater than 10 minutes in the IVY method raise concerns about coagulopathy [

7]. Any abnormalities observed would necessitate further evaluation, with particular attention to the coagulation pathway under consideration.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the bleeding time of patients in therapy with different anticoagulants and antiplatelets adapting the Ivy test to the oral environment. The null hypothesis tested was that no differences existed in bleeding time in patients in therapy with different anticoagulants and antiplatelets.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study included a consecutive cohort of 93 patients. Patients were recruited at the time of their professional oral hygiene session. If they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the present study, they were carefully informed about the study protocol and the aim of the investigation and asked if they were willing to participate.

The study was approved by the local ethical committee (CERA 2024/08) and each patient recruited provided written informed consent.

Adult patients, without contraindications to the planned oral hygiene procedures, presenting natural teeth or natural teeth supported restorations, were included if in therapy with any anticoagulant or antiplatelet. In addition, a cohort of 16 healthy patients was included as control group.

Exclusion criteria for both the test and control group were age < 18 years, pregnant or lactating women, infarct within the last 6 months, immunosuppression, uncontrolled diabetes, radiation of the head and neck region, periodontitis patients. Completely edentulous patients or patients with implant-supported restorations and no natural teeth were excluded.

For the test group, reason for drug use, dosage and time from the last intake were registered.

Patients were recalled for the biannual dental hygiene maintenance session and checkup.

Patients were asked to rinse the mouth for 1 minute with a chlorhexidine mouthwash. A periodontal calibrated probe (PCP UNC 15, Hu-Friedy) was used to evaluate the gingival bleeding starting from the vestibular side of element 1.6 by an expert operator (DP).

The initial site manifesting bleeding underwent assessment. A chronometer was started by another operator (LP) and subsequently every 15 sec gentle pressure was applied with sterile gauzes to facilitate the spontaneous hemostasis of the lesion. The timing of bleeding cessation was meticulously recorded.

After that a professional oral hygiene procedure was executed using ultrasonic mechanical instrumentation (PS – EMS) by an expert dental hygienist (LP).

Control: no anticoagulants or antiplatelets

DTI: direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran)

AntiXa: directa factor Xa inhibitors (endoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban)

VKA: vitamin K antagonists (warfarin, acenocoumarol)

SAPT: single anti-platelet therapy (acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel)

DAPT: dual anti-platelet therapy (acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel)

Bleeding time was registered in seconds and mean values were evaluated among the different groups.

We could not assume gaussian distribution of variables due to the small sample size of certain subgroups, therefore non-parametric tests for all analyses were used. Data and plots were reported as medians [interquartile range] if not otherwise stated. Differences between groups were investigated with Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc. Significance was assumed at an alpha level of 0.05.

3. Results

Ninety-three patients were included in the present research as reported in

Table 1.

Reason for drug use is reported in

Table 2. The mean reason for drug intake was atrial fibrillation, the second one was myocardial or cerebral ischemia.

The mean bleeding time was:

Control 50 [39 - 61]

DTI 120 [60 - 155]

AntiXa 98 [74 - 160]

VKA 203 [140 - 281]

SAPT 105 [50 - 120]

DAPT 190 [143 - 240]

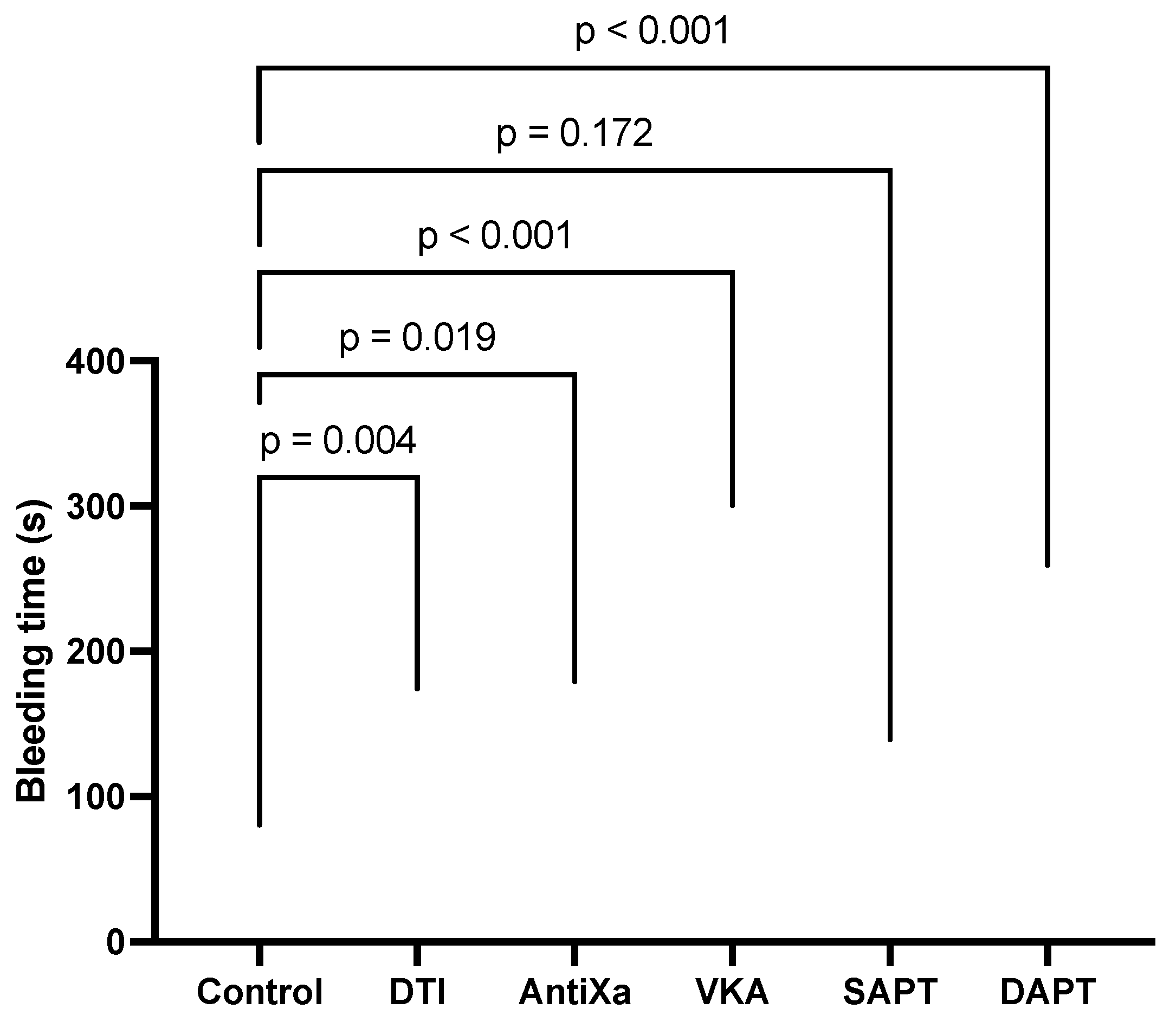

A statistically significant difference was present among control and DTI (p=0.004), VKA (p<0.001), DAPT (p<0.001) as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Bleeding time for each group and statistical significance (seconds).

Figure 1.

Bleeding time for each group and statistical significance (seconds).

The main bleeding time divided for each drug was:

APIXABAN 72 [96 - 131]

ASA 50 [100 - 138]

ASA+CLOP 143 [190 - 240]

CLOPIDOG 105 [108 - 110]

DABIGATR 60 [120 - 155]

RIVAROXA 65 [115 - 290]

SINTROM 192 [368 - 450]

WARFARIN 121 [195 - 252]

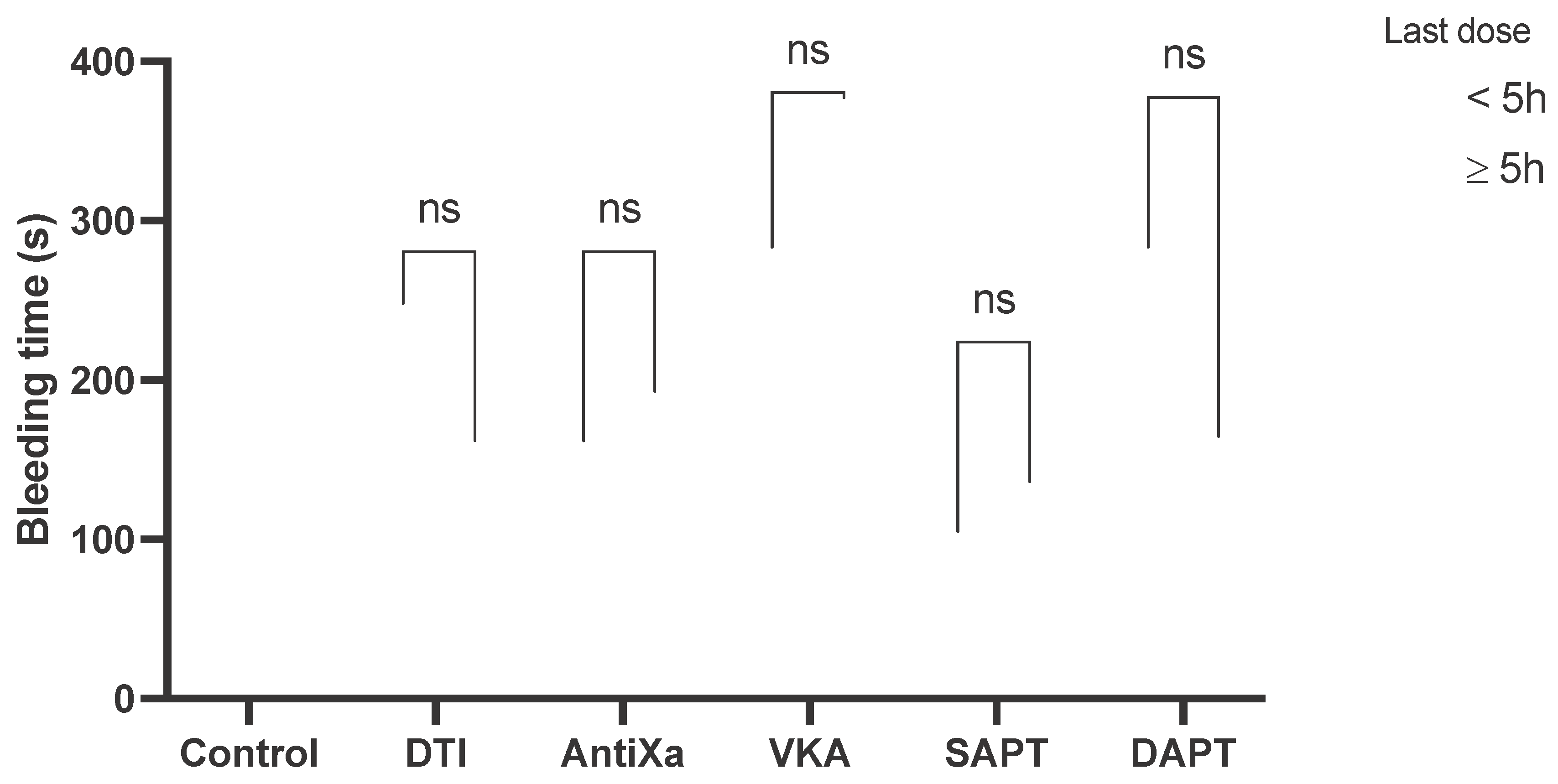

The median time elapsed from last drug dose was 5 hours, therefore patients were further classified in those that took the drug less than 5 h before the procedure versus >= 5 h (figure 3). There were no differences within categories of drugs between patients that took the last dose before or after 5h from the start of procedure.

Figure 3.

Bleeding time for group divided for time from intake (minutes).

Figure 3.

Bleeding time for group divided for time from intake (minutes).

4. Discussion

Thanks to advances in medical research and new therapeutic strategies, individuals with cardiovascular diseases have now increased life expectancies and the number of adult patients in therapy with anticoagulants and/or antiplatelets seeking for dental care is significantly increased compared to a few decades ago [

8].

Although most of common dental procedures and professional oral hygiene sessions might not represent a health concern for these patients, anticoagulant and antiplatelet medication might constitute a challenge for dentists and dental hygienists since possible prolonged bleeding might interfere with dental procedures. The adaptation of the Ivy test in the oral environment has been successful because this method was able to highlight differences among the groups and significant differences compared to the control group.

The outcomes of the present investigation highlighted a different bleeding time among the groups analyzed. VKA patients presented the longest bleeding period. Patients taking VKA had a bleeding time that was more than 2 times higher than that of healthy subjects with a statistically significant difference.

VKA present challenges due to adverse effects and interactions with certain drugs and foods. Additionally, while their antithrombotic effects typically commence 48-72 hours post-administration, the reduction of coagulation factors doesn't manifest until five days into treatment [

9]. Consequently, the clinical utilization of these medications is complicated by the necessity for meticulous monitoring of their activity. Anticoagulants necessitate precise monitoring and dosage adjustments to achieve the desired therapeutic outcome while minimizing the risks associated with both excessive anticoagulation (leading to increased risk of bleeding) and inadequate anticoagulation (resulting in increased risk of thrombosis).

The principal used VKA are acenocoumarol and warfarin.

Acenocoumarol is a VKA with a relatively short half-life of 8-10 hours, it is typically prescribed once daily and in our research induced the longest bleeding time, followed by warfarin.

Warfarin stands as the most prescribed medication for anticoagulation. It boasts an extended duration of action, characterized by a half-life spanning of 48-72 hours.

For VKA, the most invasive therapies (surgical) should be performed when the International Normalized Ratio (INR) is below 2.5, ensuring adherence to the therapeutic cardiologic range and avoiding the need to suspend anticoagulant therapy.

When the intake time was analyzed, VKA seemed not to be influenced. Both groups (intake <5 hours or >5 hours) presented a bleeding time of more than 200 seconds.

DTI and AntiXa analyzed in this research were apixabam, rivaroxabam and dabigatran.

Rivaroxaban and apixabam are administered orally as selective factor Xa inhibitors, boasting close to 100% absorption rates. Although clinical data remain limited, insights into their metabolism and potential drug interactions are primarily derived from nonclinical studies. Routine monitoring is unnecessary for these medications, similar to dabigatran [

10,

11].

Dabigatran serves as a potent inhibitor of free thrombin, thrombin bound to fibrin, and platelet aggregation induced by thrombin, effectively preventing thrombus formation. Its primary indication lies in elective total hip or knee replacement surgery, and also in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in adults with non-valvular atrial fibrillation [

12]. Notably, it does not necessitate monitoring [

10,

12,

13]. Administered orally, the recommended dosage consists of two daily doses of 110 mg. Plasma peak concentrations are typically achieved between 30 minutes and two hours following administration. With a bioavailability of 5-6%, the half-life after single and multiple dosing spans 8 and 17 hours, respectively [

12]. The majority of the drug (80%) is excreted in urine.

In the present investigation, patients assuming rivaroxabam presented the longest bleeding period followed by dabigatran and apixaban.

Even no statistically significant differences were note it is interesting to note a tendency to reduce the bleeding time 5 hours after the drug intake. For this reason it must be speculated that patient undergoes surgery in the early hours post-assumption, there is maximum anticoagulation effect with a heightened risk of bleeding. Conversely, if treated short before the next intake, the risk is diminished, if not almost negligible. Therefore, the optimal period for surgical treatment of these patients could be 2-3 hours before the next dose, without the need to temporarily suspend the medication.

Regarding antiplatelet, the drugs analyzed were cardioaspirin and clopidogrel.

Acetylsalicylic acid is absorbed in the stomach and reaches the bloodstream within 10 minutes, attaining peak plasma concentration between 30 to 40 minutes [

14]. Aspirin functions by deactivating the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase, essential for thromboxane synthesis within platelets, thereby diminishing platelet activation and aggregation [

15]. Conversely, clopidogrel serves as an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) antagonist, exerting its effects by irreversibly blocking the ADP receptor on the platelet membrane, leading to alterations in platelet morphology and decreased aggregation [

16]. Furthermore, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), comprising aspirin/clopidogrel or aspirin/P2Y12 inhibitor, is commonly employed in patients with cardiovascular disease. According to guidelines from the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association, DAPT may be recommended for the secondary prevention of acute coronary events and post-stent placement [

17]. Patients taking cardioaspirin or clopidogrel had almost the same bleeding time, conversely patients taking a combination of the two drugs presented an almost double bleeding time [

15].

In the present study, during professional oral hygiene procedures, no significant bleeding episodes have been observed in patients taking antiplatelets, even in cases of dual antiplatelet therapy. However, it is crucial to emphasize that local hemostasis was performed using gauze tamponade (a primary and effective measure). Still, the surgeon can enhance it with the use of sutures, local hemostatic drugs, and, if necessary, defined cauterizations.

Limits of the present research must be acknowledged. First of all, a power analysis was not conducted as no similar studies were found in the scientific literature. Secondarily, periodontal health parameters including bleeding on probing, probing depth or plaque index were not recorded, even if it must be reported that all the patients were included in a strict follow-up recall regimen and were evaluated at the time of their biannual professional oral hygiene session.

5. Conclusions

Based on the present outcomes, an increased risk of prolonged bleeding emerged in patients taking VKA and DAPT. However, bleeding did not interfere with the oral hygiene session The optimal period for dental treatment of these patients should be 2-3 hours before the next dose, without the need to temporarily suspend the medication. The Ivy test adapted in the oral environment could be successfully used to evaluate patient’s bleeding time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P. and D.P.; methodology, D.P.; software, P.P.; formal analysis, L.P.; investigation, F.B.; statistical analysis, L.B.; data curation, G.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, P.P. P.N.; supervision, P.P. and L.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Genoa CERA (08/2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mask, A.G., Jr. Medical management of the patient with cardiovascular disease. Periodontol 2000 2000, 23, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, Y.; Niwa, H.; Minematsu, K. Risk factors affecting postoperative hemorrhage after tooth extraction in patients receiving oral antithrombotic therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 69, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diermen, D.E.; van der Waal, I.; Hoogstraten, J. Management recommendations for invasive dental treatment in patients using oral antithrombotic medication, including novel oral anticoagulants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013, 116, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, R.T.; Dawson, D.R., 3rd; Kryscio, R.J.; Al-Sabbagh, M.; Miller, C.S. Postoperative bleeding associated with antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs: A retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2019, 128, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, J.S.; Eikelboom, J.; Douketis, J.; Wallentin, L.; Oldgren, J.; Yang, S.; Themeles, E.; Heidbuchel, H.; Avezum, A.; Reilly, P.; et al. Periprocedural bleeding and thromboembolic events with dabigatran compared with warfarin: results from the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) randomized trial. Circulation 2012, 126, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hylek, E.M.; Held, C.; Alexander, J.H.; Lopes, R.D.; De Caterina, R.; Wojdyla, D.M.; Huber, K.; Jansky, P.; Steg, P.G.; Hanna, M.; et al. Major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving apixaban or warfarin: The ARISTOTLE Trial (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation): Predictors, Characteristics, and Clinical Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 63, 2141–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielke, C.H.; Kaneshiro, M.M.; Maher, I.A.; Weiner, J.M.; Rapaport, S.I. The Standardized Normal Ivy Bleeding Time and Its Prolongation by Aspirin. Blood 1969, 34, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Tort, J.; Schiavo-Di Flaviano, V.; González-Navarro, B.; Jané-Salas, E.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; López-López, J. Update on the management of anticoagulated and antiaggregated patients in dental practice: Literature review. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry 2021, e948–e956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, Y.; Poveda, R.; Gavalda, C.; Margaix, M.; Sarrion, G. An update on the management of anticoagulated patients programmed for dental extractions and surgery. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2008, 13, E176-179. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, B.I.; Quinlan, D.J.; Eikelboom, J.W. Novel oral factor Xa and thrombin inhibitors in the management of thromboembolism. Annu Rev Med 2011, 62, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingarro-de-Leon, A.; Chaveli-Lopez, B.; Gavalda-Esteve, C. Dental management of patients receiving anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet treatment. J Clin Exp Dent 2014, 6, e155-161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firriolo, F.J.; Hupp, W.S. Beyond warfarin: the new generation of oral anticoagulants and their implications for the management of dental patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012, 113, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.W. New oral anticoagulants: will they replace warfarin? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012, 113, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.R.; Bhatt, D.L. The state of periprocedural antiplatelet therapy after recent trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2010, 3, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAgil, J.; AlDaamah, Z.; Khan, A.; Omar, O. Risk of postoperative bleeding after dental extraction in patients on antiplatelet therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calafiore, A.M.; Iaco, A.L.; Tash, A.; Mauro, M.D. Decision making after aspirin, clopidogrel and GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor use. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg 2010, 2010, mmcts 2010 004580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Gara, P.T.; Kushner, F.G.; Ascheim, D.D.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Chung, M.K.; de Lemos, J.A.; Ettinger, S.M.; Fang, J.C.; Fesmire, F.M.; Franklin, B.A.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 61, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).