1. Introduction

Clinical presentations of skin lesions in Kaposi’s sarcoma typically manifest as painless macules with a purple hue. [

1,

2] Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma cases are primarily associated with HHV8 infection, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. [

3] Apart from AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma, other types include Class type (sporadic), endemic type (African), and iatrogenic type (immunosuppression-related), which are relatively uncommon in clinical practice. [

4]

Regarding treatment protocols outlined in the literature, therapies for HIV-positive cases adhere to standard rules and NCCN guidelines. [

5] Treatment approaches for identified Kaposi’s sarcoma vary based on lesion classification. For asymptomatic limited cutaneous lesions, observation along with antiretroviral therapy (ART) is recommended initially, whereas symptomatic limited cutaneous lesions may require ART combined with topicals, systemic therapy, intralesional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or local excision. Advanced cutaneous, oral, visceral, or nodal lesions may necessitate ART along with radiotherapy, systemic therapy, or participation in clinical trials.[

6,

7,

8] However, there is no standardized treatment protocol for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma. [

9]

In general, elective surgery becomes an option when localized skin lesions become problematic and surgical intervention is feasible. [

10] Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess the outcomes in non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients treated through surgical methods, with the hope of identifying meaningful disparities in treatment outcomes associated with surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

Our trial was a single-center, pragmatic, retrospective study that aimed to compare outcomes among non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients treated with surgical wide excision or those who were not treated with surgery.

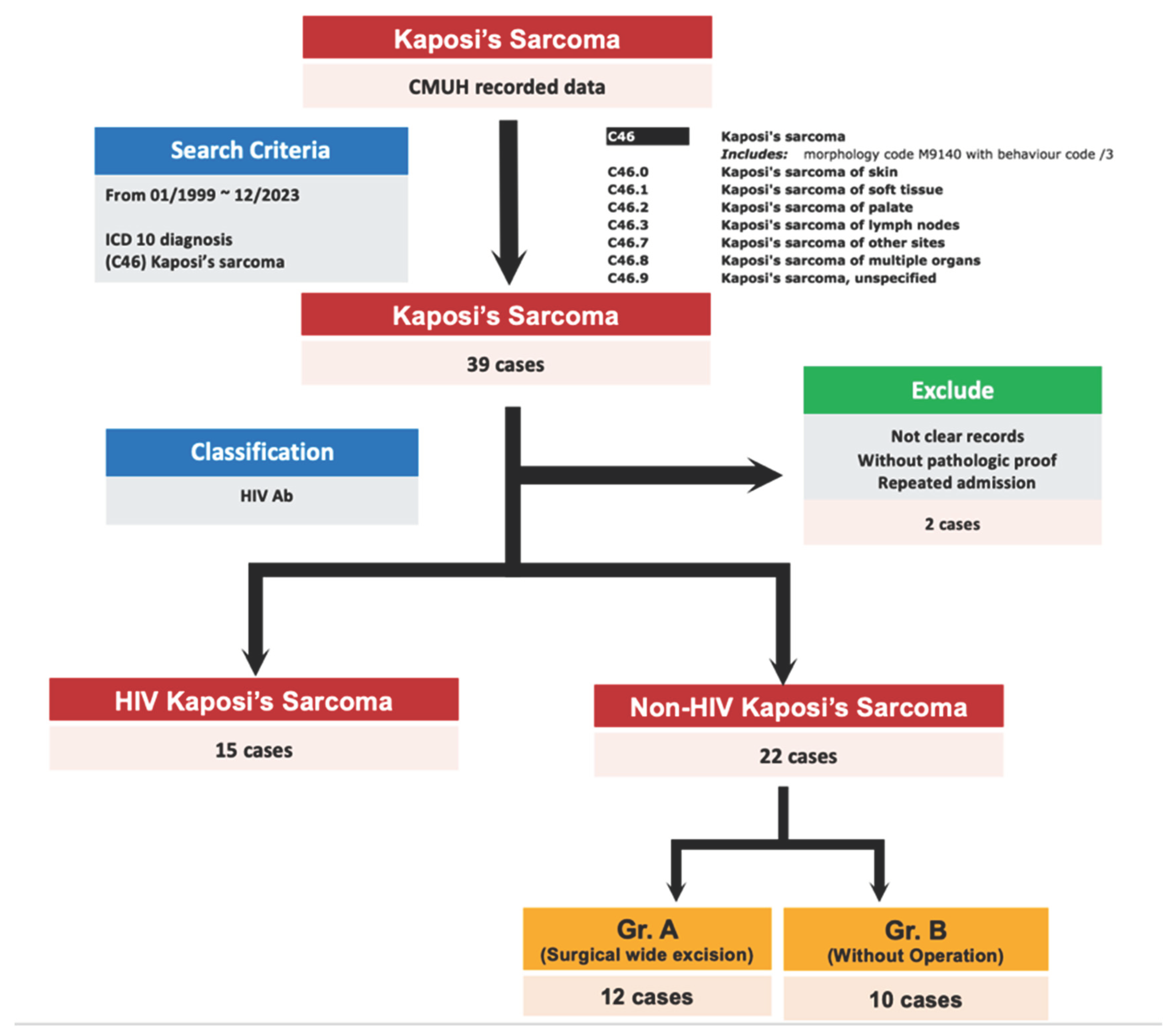

We identified cases with an ICD diagnosis (C46: Kaposi’s sarcoma) at CMUH from 1990 to 2023. Over the 30-year period, 39 cases were initially identified. After excluding 2 cases due to inadequate data to avoid misinterpretation, we were left with 37 cases. These cases were then divided into two groups based on HIV status: Kaposi’s sarcoma with HIV and without HIV. Among these, 22 cases were classified as non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma (

Figure 1).

We collected basic data from these cases, including age, sex, comorbidities, diagnosed Kaposi’s sarcoma data, Kaposi’s sarcoma lesion site and features, staging (European Journal of Dermatology staging), patient’s immunosuppressive status, associated disorders, performance status at the time of diagnosis, treatment modalities (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, operation, combined therapy), follow-up time, symptom-free time, response to treatment, and cause of death if the patient passed away.

Among the 22 non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma cases, we further categorized them into two groups based on whether they underwent surgical wide excision or not. Consequently, 13 cases had undergone the operation for Kaposi’s sarcoma (group A), while the remaining 9 cases had not undergone the operation (group B) (

Figure 1). We aimed to compare the differences in outcomes between these two groups, especially regarding the follow-up period and survival rate.

A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance for the outcome. Analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 28, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test method.

3. Results

As previously mentioned, non-HIV patients accounted for 59% (22/37) of Kaposi’s sarcoma cases in our trial. Among these 22 non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma cases, 90.9% of the cases were male, with a mean diagnosed age of 69.7 years old. Additionally, 90.9% (20/22) of the cases had localized lesions located at the lower extremities, and 68% (15/22) of the cases died during the follow-up period, which continued until loss to follow-up or death.

All clinical characteristics and outcome analyses are presented below.(

Table 1) In group A (13 cases), 7 cases were stage I, 5 cases were stage II, and 1 case was stage IV. In group B (9 cases), 2 cases were stage I, 5 cases were stage II, 1 case was stage III, and 1 case was stage IV. The distribution of staging cases between the two groups was similar and not statistically significant, with most cases falling into early stages (I and II). Associated skin lesions and treatment methods are outlined below.(

Table 2) In group A, 11 cases had a Karnofsky scale greater than 70, 1 case had a scale between 50 to 70, and 1 case had a scale less than 50. In group B, 5 cases had a Karnofsky scale greater than 70, 1 case had a scale between 50 to 70, and 3 cases had a scale less than 50.

Regarding therapeutic methods, in group A, 6 cases only underwent surgical wide excision, 1 case also underwent radiotherapy and chemotherapy, 2 cases also received chemotherapy, and 4 cases also received radiotherapy. In group B, 4 cases received chemotherapy, 4 cases received radiotherapy, and 1 case did not receive any treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma due to other underlying diseases with higher priority and subsequent loss to follow-up.

Regarding follow-up periods, the median follow-up time was 61 months and the mean follow-up time was 60.15 months in group A, while the median follow-up time was 33 months and the mean follow-up time was 43.44 months in group B. There was no significant difference in mean follow-up time (P = 0.796).

In terms of outcomes, a higher rate of complete response was observed in group A (61.5% complete response, 23% partial response, and 15.3% poor response) compared to group B (22% complete response, 44% partial response, and 33% poor response). Mortality rates were similar between the two groups, with various causes including pancreatic cancer, septic shock, stroke, and unknown reasons.

Regarding postoperative complications, only one case in group A experienced wound site cellulitis, while another case suffered from wound site verrucous plantaris. As for symptom-free time, 10 out of 13 cases in group A experienced symptom-free periods after receiving wide excision, whereas only 2 cases had symptom-free periods after treatment in group B. Most cases in group B that did not receive surgical wide excision continued to experience symptoms.

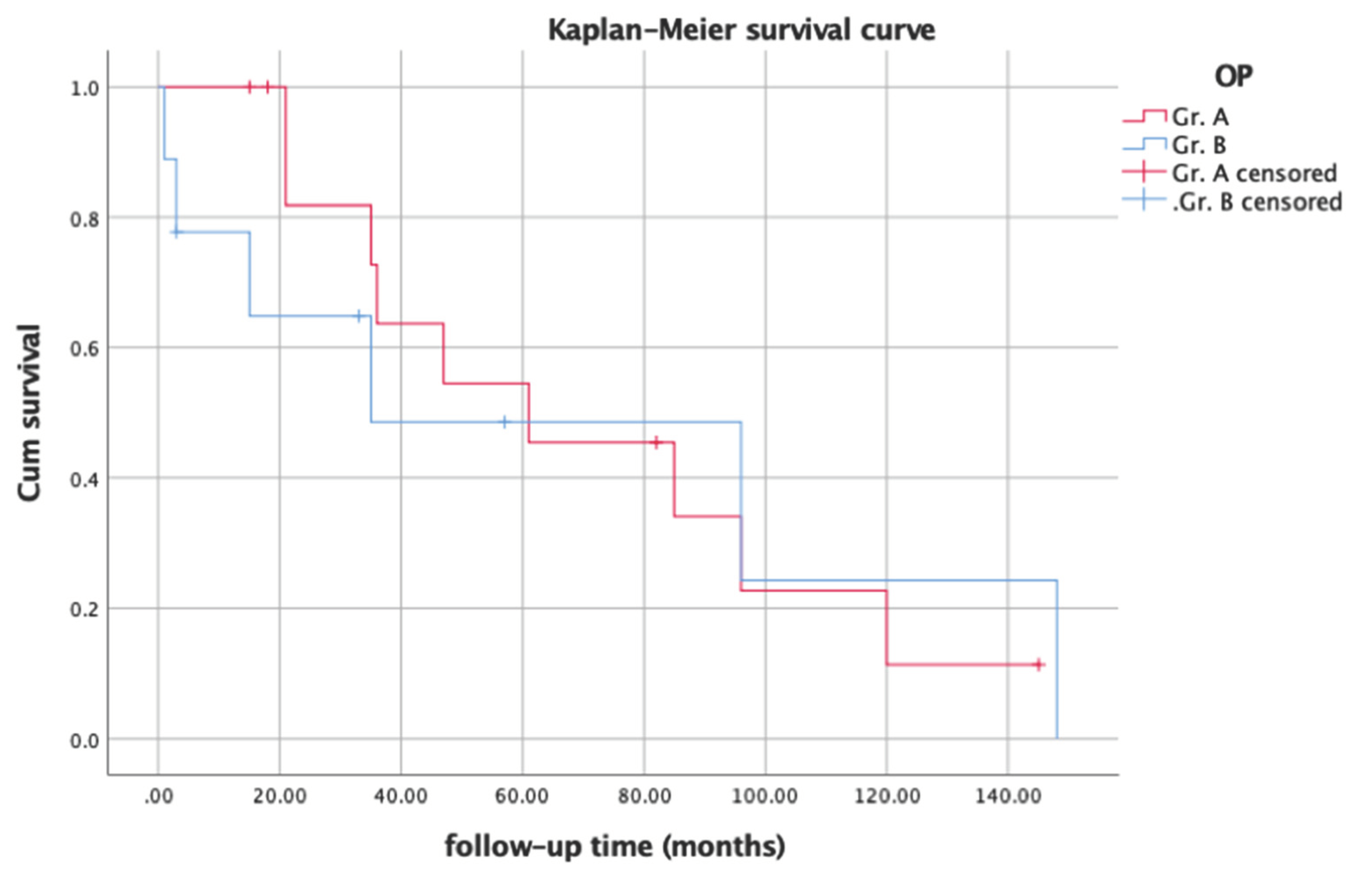

In evaluating prognosis among non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients, we compared follow-up periods and survival rates between the groups using Kaplan-Meier curves. (

Figure 2) Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference (P = 0.046) in survival rates by log-rank test, possibly due to the higher survival rate noted during the first 5-year follow-up period in group A.

4. Discussion

Histologically, in the process of skin lesion formation in Kaposi’s sarcoma, thin-walled vascular spaces are visible in the upper dermis, accompanied by a sparse mononuclear cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. Subsequently, spindle cell bundles accumulate around areas of angioproliferation. Larger fascicles of spindle-shaped endothelial cells accumulate, resulting in fewer and more compact vascular slits, leading to the development of well-defined nodules and a more solid tumor. This histological progression may explain why skin lesions in non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma cases are more limited and localized[

11]. Additionally, lymphangioma-like skin lesions are more common in non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma, consisting of networks of irregular dilated lymphatics lined by flat and cytologically banal endothelial cells, presenting as compressible nodules resembling fluid-filled cysts. [

12]

Due to the scarcity of non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma cases, published treatment options are primarily based on retrospective studies and case reports. Consequently, there are no established treatment guidelines for this condition. The relative rarity of the disease, the presence of comorbidities limiting treatment options, and challenges in participation in clinical trials make it challenging to conduct prospective randomized trials comparing different treatments. Therefore, non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients typically undergo treatments based on the attending physician’s experience and individual response[

13,

14]. Common therapies include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and combined operation for localized skin lesions.

In some literature reviews, the overall 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma were reported as 92%, 69%, and 46% respectively after diagnosis, with a median survival time of 9.6 years[

15]. The rate in the status of stable condition (persistent disease) is 15% and disease free is 35% in median 6-year follow-up[

16,

17]. However, there is a significant gap in treatment outcomes among non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. The leading causes of death in these patients include secondary malignancy (24%) and iatrogenic diseases (22%).11,12

Regarding performance status assessment, the Karnofsky scale was chosen due to its precision in reflecting physical status compared to the ECOG scale. The cases were categorized into three groups based on their Karnofsky scores: greater than 70, between 50 to 70, and less than 50. A Karnofsky score greater than 70 indicates normal activities with effort and is commonly used to evaluate the stage in HIV-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. This score has been identified as an important prognostic factor in HIV-related Kaposi’s sarcoma in some literature. On the other hand, a Karnofsky score less than 50 signifies that cases require considerable assistance and frequent medical care, marking a critical turning point in the patient's condition.

About Kaplan-Meier curve, the statistical analysis reveals a p-value of 0.046, indicating a significant difference in the survival curve. This significant difference could be attributed to the higher survival rate observed in Group A during the first 5-year follow-up period. This suggests that patients who underwent surgery for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma may experience better outcomes and survival rates in the initial 5 years following treatment. This finding underscores the potential benefit of surgical intervention in the management of non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma, particularly in the short to medium-term survival outcomes.

Additionally, most of the cases in group A experienced monthly symptom-free time. However, there is limited literature discussing the relationship between non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma and surgery. Despite the lack of comprehensive research in this area, the findings of this study suggest that elective surgery may lead to better outcomes and survival rates in non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients[

17]. Therefore, surgical intervention for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma as a crucial therapeutic treatment should be concerned.

Despite the fact that NCCN guidelines exclusively offer treatment recommendations for AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma, certain therapies outlined in these guidelines may serve as a reference for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma. Elective surgery combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy could potentially be an effective treatment approach for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma. While these recommendations are not explicitly specified for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma, the principles of treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma may be applicable across various contexts, including non-HIV-related cases. However, individualized treatment plans should be formulated based on the specific characteristics of each patient and the extent of the disease. Further research and clinical studies are warranted to determine the efficacy and optimal treatment strategies for non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma.

The study has several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, it was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Additionally, the study included a relatively small number of cases, which could impact the statistical power and reliability of the results.

Furthermore, the pragmatic study design relied on data collection from electronic medical records, which may have led to limitations in obtaining detailed patient characteristics and clinical information. This could potentially introduce outcome ascertainment bias and affect the accuracy of the results.

The small number of cases in the study may have influenced the statistical analysis, making it challenging to detect significant differences between groups. Moreover, the cases were managed by different attending physicians, potentially resulting in variations in the management and assessment of Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions.

The duration of follow-up for survival rate assessment may also be a limitation. The cut-off observation days were determined based on the last outpatient clinic visit, which could result in varying lengths of follow-up among the cases. This variability in follow-up duration could impact the statistical power of the analysis and the interpretation of the results.

In summary, while the study provides valuable insights into the treatment of non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma, its limitations highlight the need for larger, multi-center studies with longer follow-up periods to further elucidate the efficacy and outcomes of different treatment approaches. Further investigation and larger studies are needed to validate and better understand the potential benefits of surgery in the management of non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this retrospective study involving non-HIV-infected adults treated with surgery or alternative modalities did not demonstrate a significant difference in the primary outcome between patients who underwent surgery and those who did not. However, notable findings included a relatively lower death rate observed in the early periods and better outcomes in terms of symptom-free time in Group A, which underwent surgical wide excision. These findings may be attributed to the potentially better clinical status of patients in Group A, characterized by more localized skin lesions and a more suitable physical condition for surgical intervention. Additionally, patients who received surgical wide excision instead of radiotherapy or chemotherapy may have experienced fewer side effects and discomfort associated with these alternative therapies.

While many retrospective studies have reported long-term experiences following patients with standardized conditions, these findings may not directly apply to non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. However, there is a growing recognition of the need for guidelines and standardized techniques in the management of non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma. It is hoped that the wider adoption of such guidelines will lead to greater standardization of staging criteria and management protocols for the treatment of non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Chia-Kai Hsu, Fang-Yu, Hsu, and Chang-Cheng Chang; methodology, Chia-Kai Hsu; software, SPSS software, version 28; validation, Chang-Cheng Chang and Hung-Chi Chen; formal analysis, Chia-Kai Hsu; investigation, Chia-Kai Hsu; resources, Chia-Kai Hsu; data curation, Chia-Kai Hsu; writing—original draft preparation, Chia-Kai Hsu; writing—review and editing, Chang-Cheng Chang and Hung-Chi Chen; supervision, Chang-Cheng Chang; project administration, Chang-Cheng Chang; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University & Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (protocol code: CMUH112-REC1-188 and date of approval: Jan. 31, 2024 ).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tourlaki, A.; Bellinvia, M.; Brambilla, L. Recommended surgery of Kaposi’s sarcoma nodules. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2014, 26, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, L.; Metzler, G.; Chen, K.-M.; Garbe, C. Non-AIDS Associated Kaposi's Sarcoma: Clinical Features and Treatment Outcome. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e18397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.d.O.; Marinho, P.D.N.; Medeiros, L.D.d.S.; de Paula, V.S. Human Gammaherpesvirus 8 Oncogenes Associated with Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, L.; Genovese, G.; Berti, E.; Peris, K.; Rongioletti, F.; Micali, G.; Ayala, F.; DELLA Bella, S.; Mancuso, R.; Pinton, P.C.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of classic and iatrogenic Kaposi's sarcoma: Italian recommendations. G. Ital. di Dermatol. e Venereol. 2021, 156, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, E.; Suneja, G.; Ambinder, R.F.; Ard, K.; Baiocchi, R.; Barta, S.K.; Carchman, E.; Cohen, A.; Crysler, O.V.; Gupta, N.; et al. AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma, Version 2.2019. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, M.; Weir, J.; Francis, N.; Newsom-Davis, T.; Powles, S.; Crook, T.; Boffito, M.; Gazzard, B.; Nelson, M. The effect of HAART in 254 consecutive patients with AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS 2009, 23, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Sabranski, M.; Esser, S. HIV-Associated Kaposi's Sarcoma. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2017, 40, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, M.; Pria, A.D.; Coyle, C.; Andrews, E.; Tittle, V.; Dhoot, S.; Nelson, M. Prospective Stage-Stratified Approach to AIDS-Related Kaposi's Sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Y.C.C.; Tam, Y.C.S.; Oh, C.C. Treatments for AIDS/HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taskin, S.; Yasak, T.; Mentese, S.T.; Yilmaz, B.; Çolak, O. Kaposi’s sarcoma management from a plastic surgery perspective. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantanowitz, L.; Duke, W. Lymphoedematous variants of Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008, 22, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addula, D.; Das, C.J.; Kundra, V. Imaging of Kaposi sarcoma. Abdom. Imaging 2021, 46, 5297–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, B.; Rakowsky, E.; Katz, A.; Gutman, H.; Sulkes, A.; Schacter, J.; Fenig, E. Tailoring treatment for classical Kaposi's sarcoma: comprehensive clinical guidelines. Int. J. Oncol. 1999, 14, 1097–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla L, Boneschi V, Taglioni M, Ferrucci S. Staging of classic Kaposi's sarcoma: a useful tool for therapeutic choices. Eur J Dermatol. 2003 Jan-Feb;13(1):83-6. PMID: 12609790.

- Franceschi, S.; Arniani, S.; Balzi, D.; Geddes, M. Survival of classic Kaposi's sarcoma and risk of second cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1996, 74, 1812–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiatt, K.M.; Nelson, A.M.; Lichy, J.H.; Fanburg-Smith, J.C. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: A clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod. Pathol. 2008, 21, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurrida, S.; Bartoli, C.; Nolé, F.; Agresti, R.; Del Prato, I.; Colleoni, M.; Bajetta, E. Classic Kaposi's Sarcoma: A Review of 90 Cases. J. Dermatol. 1992, 19, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).