Submitted:

26 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Affiliative Behaviour, Prosocial Behaviour, Cooperation, Altruism, Helping Behaviour

1.2. Rescue Behaviour: Definition and Criteria

1.3. Rescue Behaviour in Vertebrates

1.4. Ant Rescue Behaviour: Contexts and Bioassays

1.5. Cognitive Abilities of Social Insects

1.6. Cognitive Aspects of Ant Rescue Behaviour

1.7. The Aim of the Present Study

1.8. Ants Used as Subjects in This Study: Species and Worker Status

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ants

2.2. Tests

2.2.1. Preliminary Preparations

2.2.2. Nestmate Rescue Tests

2.3. Analysis of Behavioural Recordings

2.3.1. Behavioural Categories Quantifying Rescue Attempts

2.3.2. Behavioural Categories Quantifying Other Behaviour Patterns Displayed by the Ants during Nestmate Rescue Tests

2.4. Statistical Analysis of the Data

2.4.1. Variables Calculated to Quantify Ant Rescue Behaviour

2.4.2. Statistical Tests Used in the Analysis of the Data

3. Results

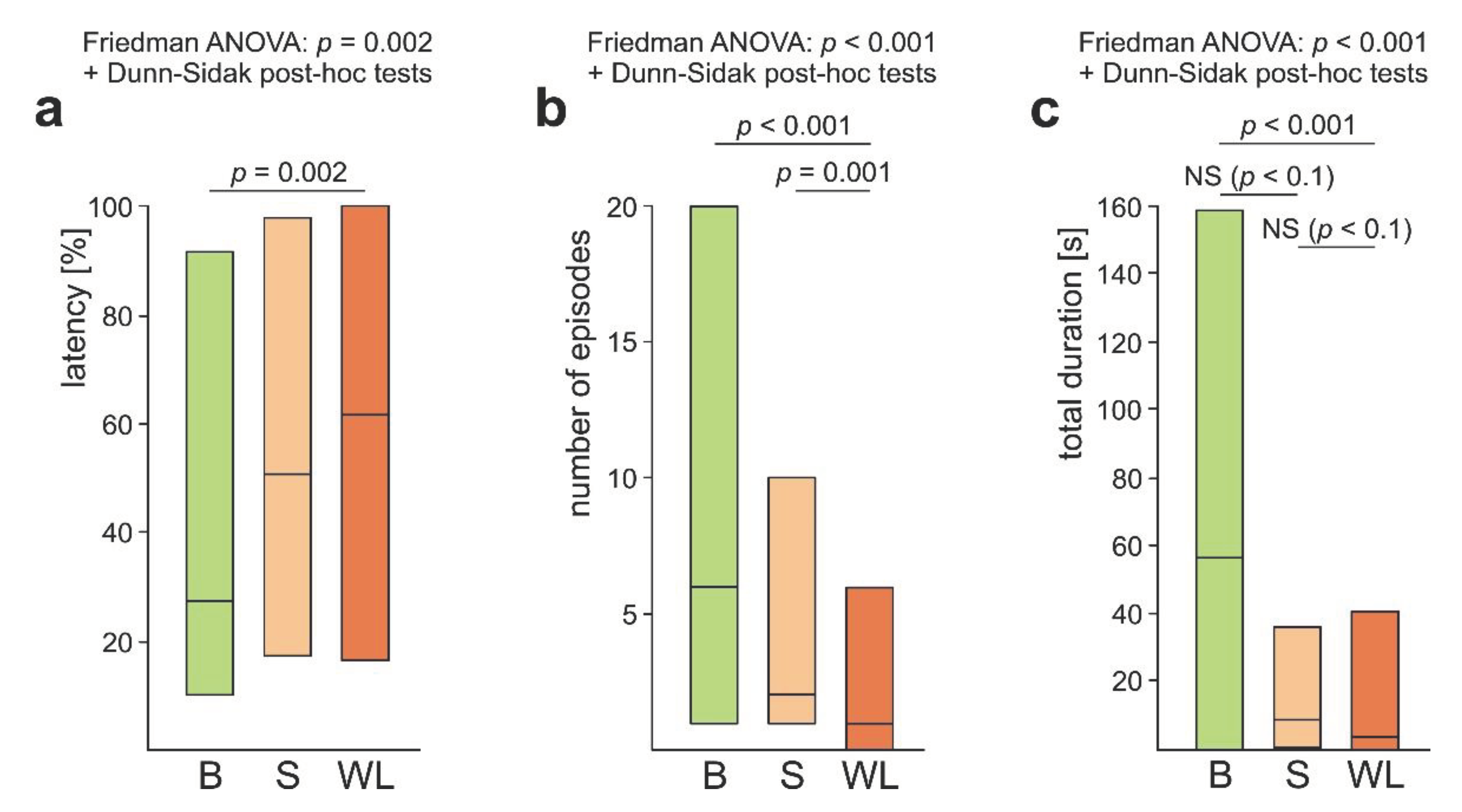

3.1. Occurrence of Rescue Behaviour during Artificial Snare Bioassays

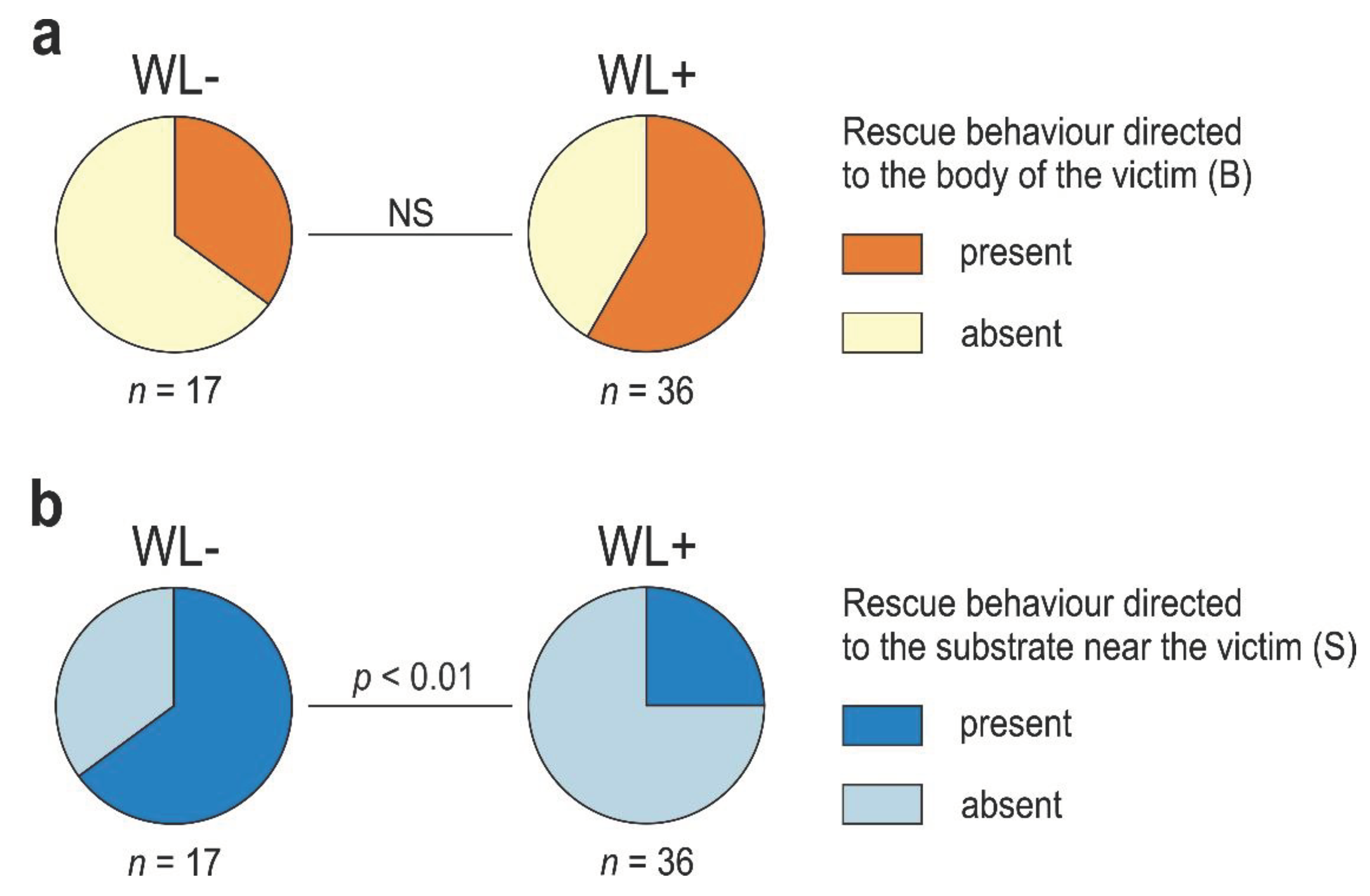

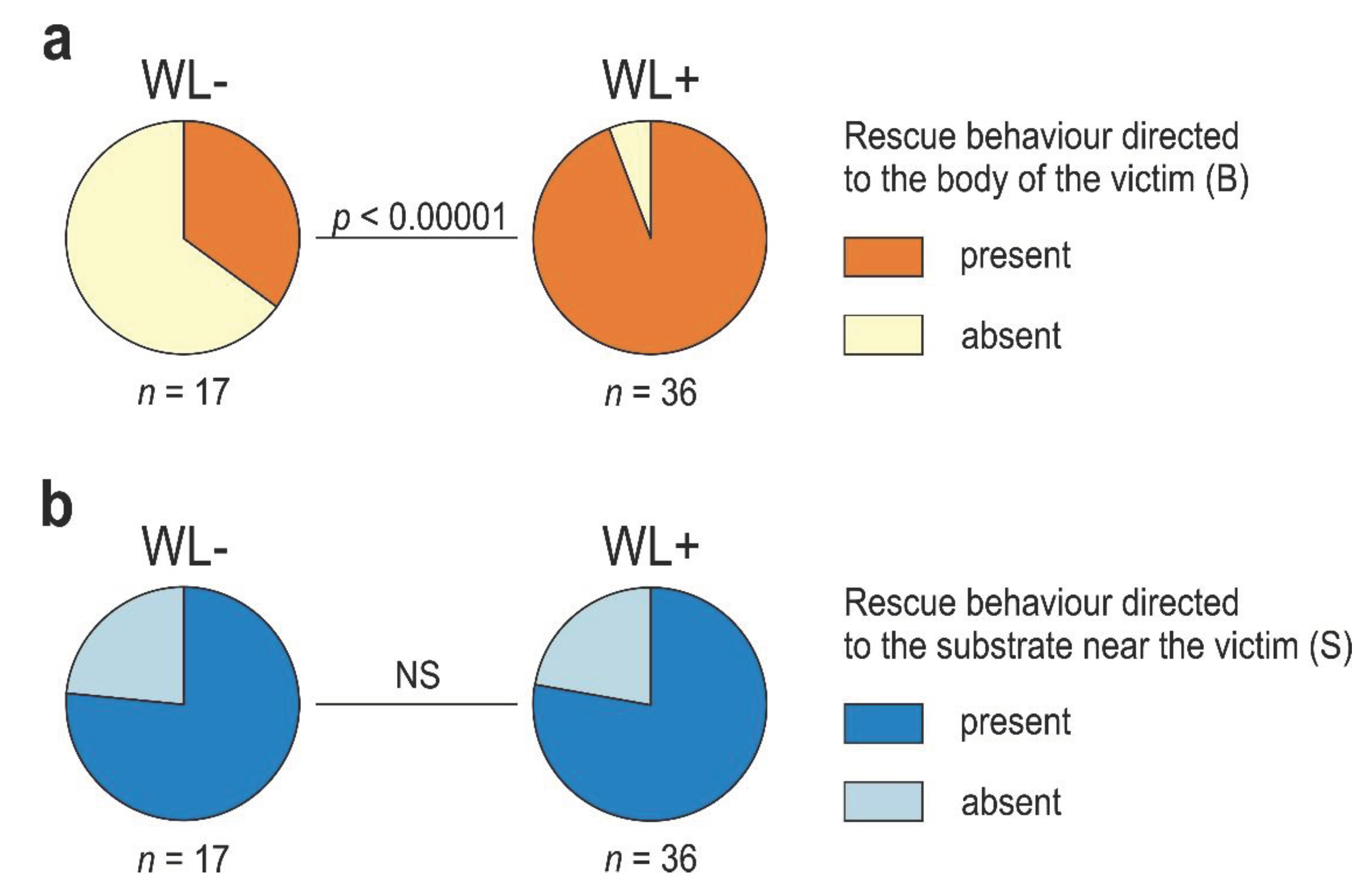

3.2. Occurrence of Various Subcategories of Rescue Behaviour

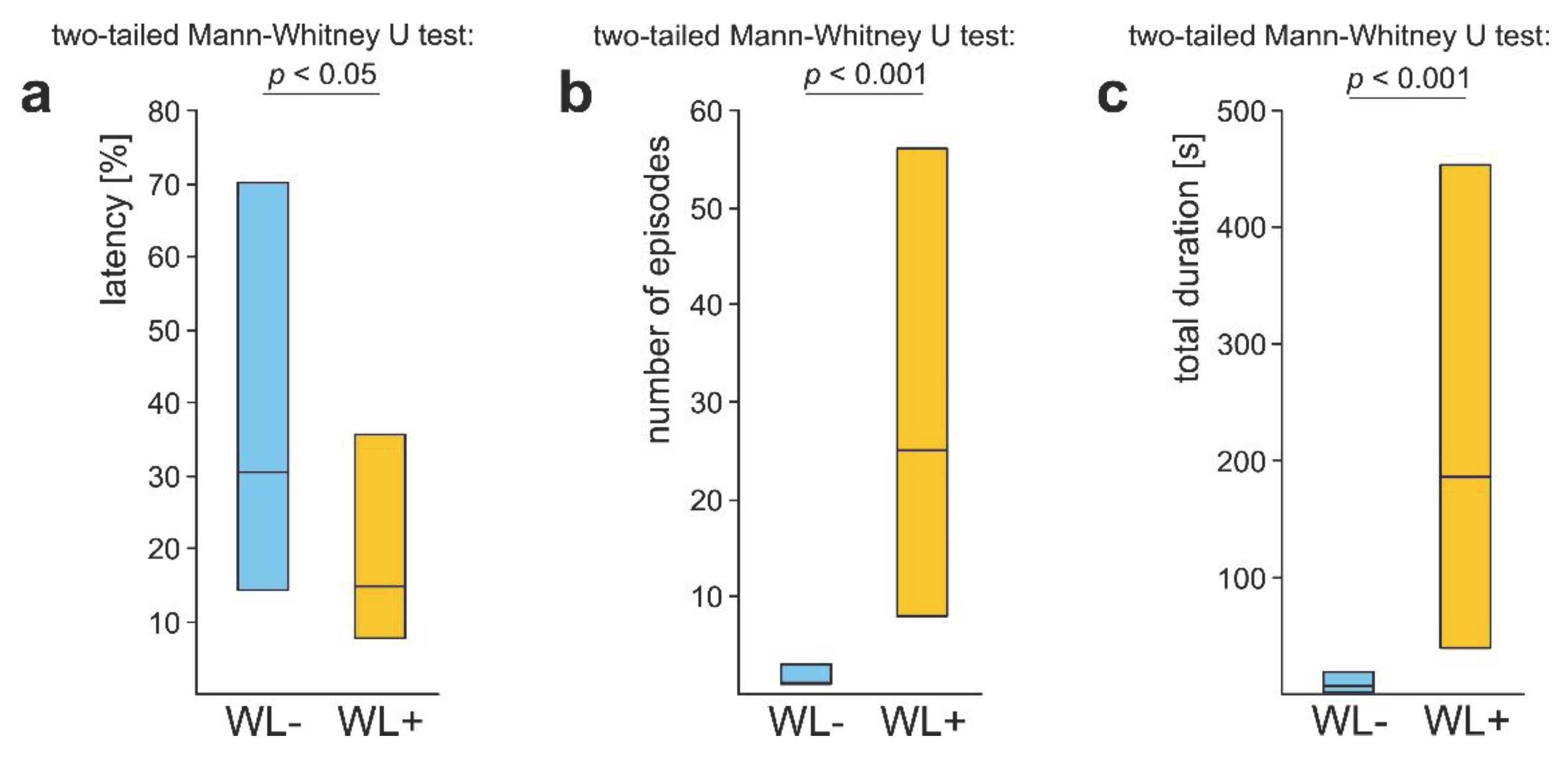

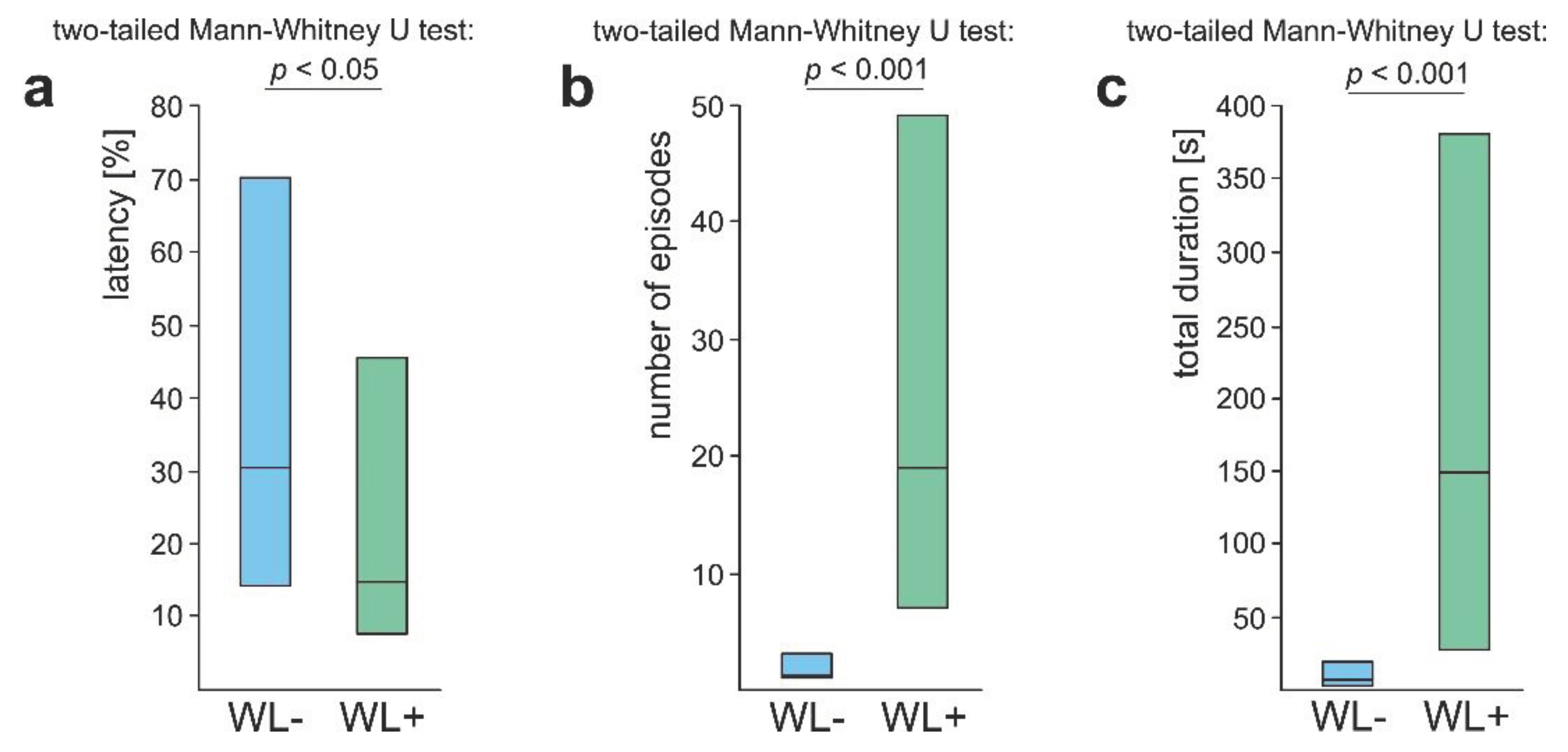

3.3. WL- Ants

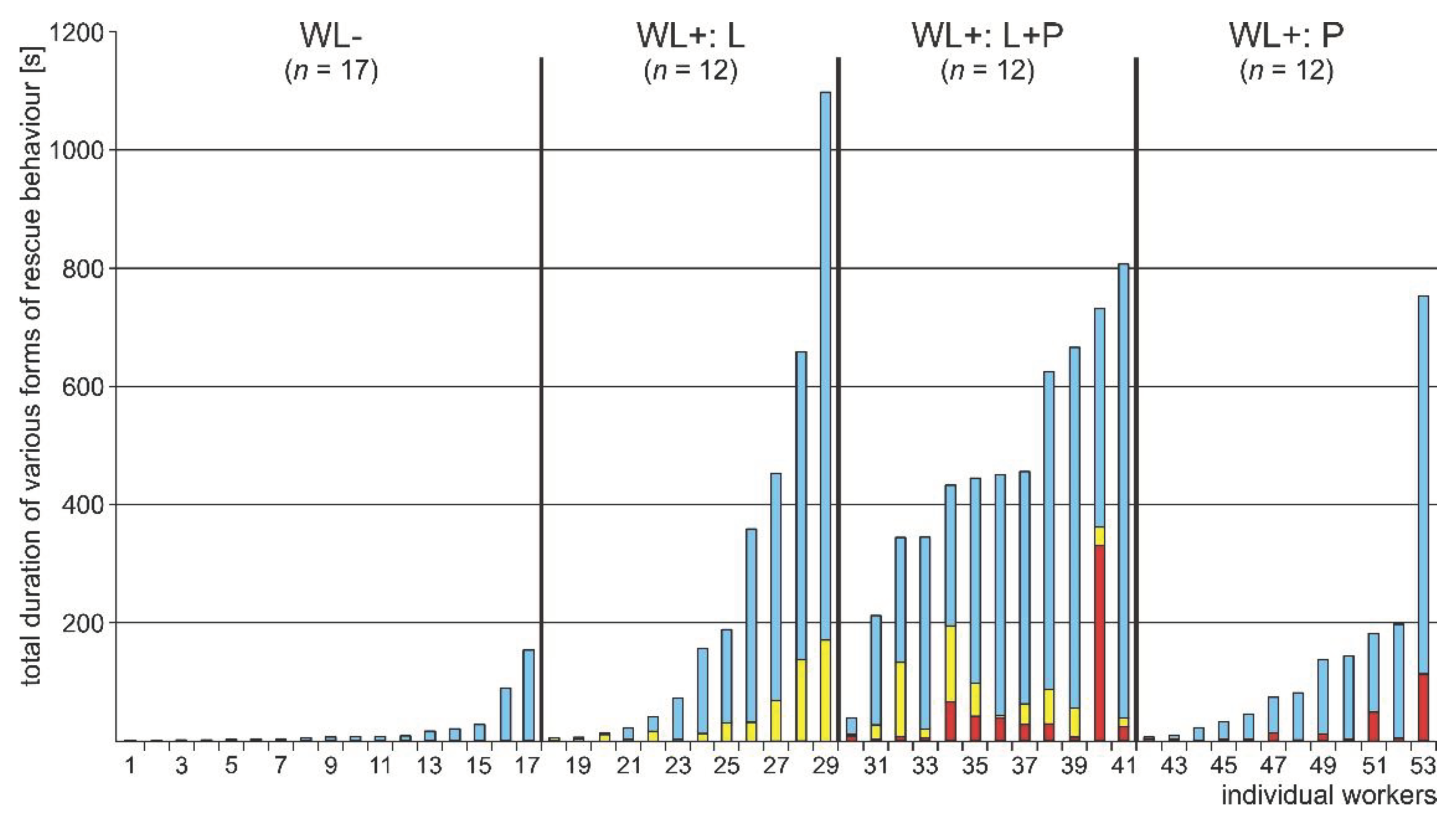

3.4. WL+ Ants and Their Comparisons with WL- Ants

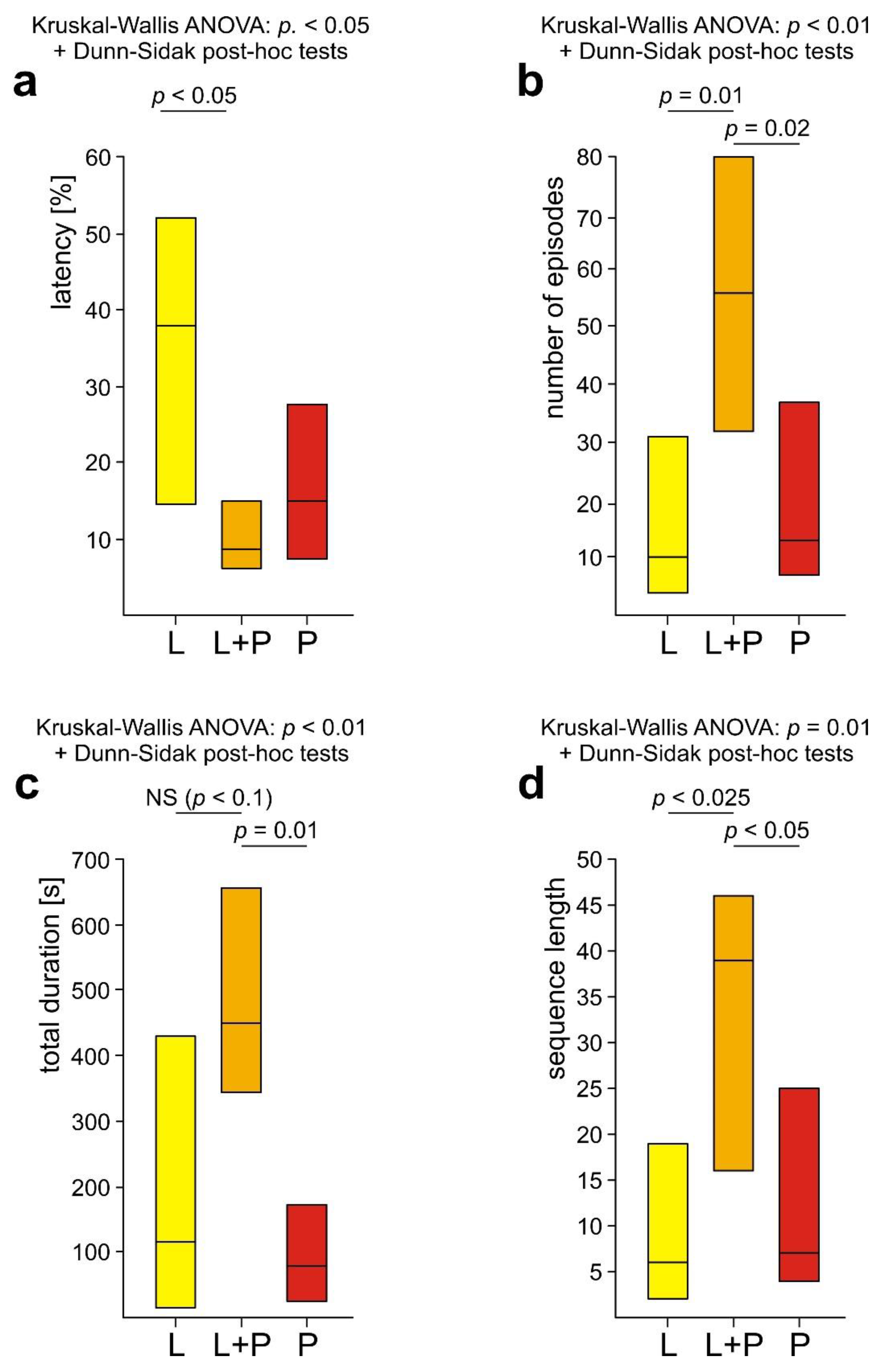

3.5. Comparison of Rescue Behaviour Performed by Workers from Various Subgroups of WL+ Ants (L, L+P and P)

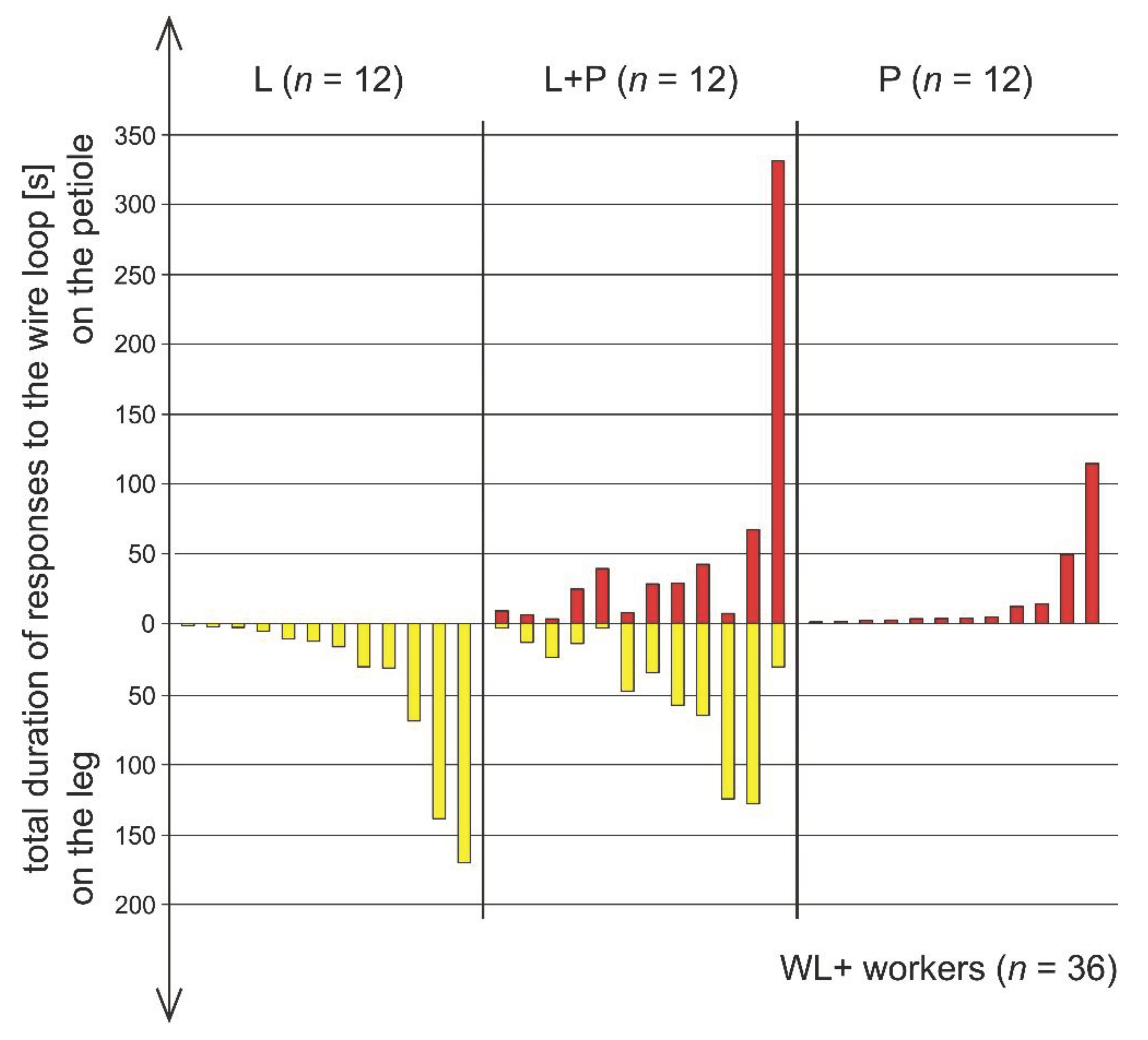

3.6. Comparison of Rescue Behaviour Directed to the Wire Loop on the Victim’s Leg (L) and on Its Petiole (P)

4. Discussion

4.1. Occurrence of Rescue Behaviour and Its Subcategories

4.2. Behavioural Profiles of Workers of Formica Polyctena

4.3. Absence of Preference for the Wire Loop Acting as a Snare

4.4. Behavioural Profiles of the Most Active and the Least Active Rescuers

4.5. Other Results Shedding Light on Cognitive Aspects of Rescue Behaviour of Workers of Formica Polyctena

4.6. Importance of the Results of this Study and the Need of Further Comparative Research

4.8. Perspectives of Future Research

4.9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poole, T.B. 1985. Competitive and affiliative behaviour. In Social behaviour in mammals. Tertiary Level Biology; Poole, T.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 82–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso del Toro, C.; Nekaris, K.A. Affiliative behaviors. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ami Bartal, I.; Decety, J.; Mason, P. Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science 2011, 334, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ami Bartal, I.; Rodgers, D.A.; Bernandez Sarria, M.S.; Decety, J.; Mason, P. Pro-social behavior in rats is modulated by social experience. Elife 2014, 3, e01385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ami Bartal, I.; Shan, H. : Molasky, N.M.; Murray, T.M.; Williams, J.Z.; Decety, J.; Mason, P. Anxiolytic treatment impairs helping behavior in rats. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronin, K.A. Prosocial behavior in animals: the influence of social relationships, communication and rewards. Anim. Behav. 2012, 84, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.; Hollis, K.; Nowbahari, E.; Kacelnik, A. Pro-sociality without empathy. Biol. Lett. 2012, 8, 910–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunfield, K.A. A construct divided: prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Bartal, I. B.-A.; Uzefovsky, F.; Knafo-Noam, A. Empathy as a driver of prosocial behaviour: highly conserved neurobehavioural mechanisms across species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 2015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowbahari, E.; Lenoir, A.; Hollis, K.L. Prosocial behavior and interindividual recognition in ants. From aggressive colony defense to rescue behavior. In: Social cognition. Development across the life span. Sommerville, J.; Decety, J. Eds.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2016b; pp. 21-43.

- Silva, P.R.R.; Silva, R.H.; Lima, R.H.; Meurer, Y.S.; Ceppi, B.; Yamamoto, M.E. Are there multiple motivators for helping behavior in rats? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keysers, C.; Knapska, E.; Moita, M.A.; Gazzola, V. Emotional contagion and prosocial behavior in rodents. TiCS 2022, 26, 688–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, M.J.; Brosnan, S. F. Pro-social behavior . In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 5720–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugatkin, L.A. Cooperation among animals: An evolutionary perspective; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, L.; Keller, L. The evolution of cooperation and altruism - a general framework and a classification of models. J. Evol. Biol. 2006, 19, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, S.F; Bshary, R. Cooperation and deception: from evolution to mechanisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2593–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowbahari, E.; Hollis, K.L. Rescue behavior: distinguishing between rescue, cooperation, and other forms of altruistic behavior. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2010, 3, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis, K.L.; Nowbahari, E. Toward a behavioral ecology of rescue behavior. Evol. Psychol. 2013b, 11, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miler, K.; Turza, F. “O sister, where art thou? ”- A review on rescue of imperiled individuals in ants. Biology 2021, 10, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.D. The evolution of altruistic behavior. Am. Nat. 1963, 97, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.A.; Gardner, A. Altruism, spite, and greenbeards. Science 2010, 327, 1341–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akins, C.K. Altruism. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, T.; Keller, L.; Lehmann, L. The evolution of altruism and the serial rediscovery of the role of relatedness. PNAS 2020, 117, 28894–28898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bshary, R.; Bergmüller, R. Distinguishing four fundamental approaches to the evolution of helping. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 21, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landabur, R.; Laborda, M.A.; Miguez, G.; Wilson, J.E. Helping behavior. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3055–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rood, J. P. Banded mongoose rescues pack member from eagle. Anim. Behav. 1983, 31, 1261–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, W.; Godzińska, E.J.; Kozłowski, M.W. Rescue behaviour shown by workers of Formica sanguinea Latr, F. fusca L. and F. cinerea Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in response to their nestmates caught by an ant lion larva. Ann. Zool. 2002, 52, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Nowbahari, E.; Scohier, A.; Durand, J.-L.; Hollis, K.L. Ants, Cataglyphis cursor, use precisely directed rescue behavior to free entrapped relatives. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, K.L.; Nowbahari, E. Cause, development, function, and evolution: toward a behavioral ecology of rescue behavior in ants. Learn. Behav. 2022, 50, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Tan, L.; Tate, K.; Okada, M. Rats demonstrate helping behavior toward a soaked conspecific. Anim. Cogn. 2015, 18, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blystad, M.H.; Andersen, D.; Johansen, E.B. Female rats release a trapped cagemate following shaping of the door opening response: opening latency when the restrainer was baited with food, was empty, or contained a cagemate. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheiro, J.; Seara-Cardoso, A.; Mesquita, A.R.; de Sousa, L.; Oliveira, P.; Summavielle, T.; Magalhães, A. Helping behavior in rats (Rattus norvegicus) when an escape alternative is present. J. Comp. Psychol. 2019, 133, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.S.; Reichel, C.M. Rats display empathic behavior independent of the opportunity for social interaction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Suemitsu, S.; Murakami, S.; Kitamura, N.; Wani, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Ishihara, T. Helping-like behaviour in mice towards conspecifcs constrained inside tubes. Sci. Rep. 2019a, 9, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlik, J.L.; Vieira Sugano, Y.Y.; Jacobi, M.C.; Kukreja, R.R.; Clement Jacobi, J.H.C.; Mason, P. The bystander effect in rats. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, A.; Okada, M.; Masuda, M.; Sato, N. Oxytocin administration modulates rats’ helping behavior depending on social context. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 153, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, K.A.; Brown, M.F. No preference for prosocial helping behavior in rats with concurrent social interaction opportunities. Learn. Behav. 2021, 49, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Gamboa, R.; Hernández, L.A.; Reynoso-Cruz, J.E.; Nieto, J. Helping behavior in rats may be facilitated by social learning. Psykhe 2021, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzański, J.; Dobrzańska, J. Reflections on ant group activities. True collaboration or joint action? Kosmos 1987, 36, 61–75. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Godzińska, E.J.; Szczuka, A.; Korczyńska, J. Rescue behaviour and sanitary care in the ants. Kosmos 2022, 71, 279–296, (in Polish, with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godzińska, E.J. Earth: planet of the ants. Academia 2004, 3, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Godzińska, E.J.; Korczyńska, J.; Szczuka, A. Dyadic nestmate reunion test in the research on ant social behavior. Kosmos 2019, 68, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masilkova, M.; Ježek, M.; Silovský, V.; Faltusová, M.; Rohla, J.; Kušta, T.; Burda, H. Observation of rescue behaviour in wild boar (Sus scrofa). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberberg, A.; Allouch, C.; Sandfort, S.; Kearns, D.; Karpel, H.; Slotnick, B. Desire for social contact, not empathy, may explain “rescue” behavior in rats. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachiga, Y.; Schwartz, L.P.; Silberberg, A.; Kearns, D.N.; Gomez, M.; Slotnick, B. Does a rat free a trapped rat due to empathy or for sociality? J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2018, 110, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomek, S.E.; Stegmann, G.M.; Foster Olive, M. Effects of heroin on rat prosocial behavior. Addict. Biol. 2019, 24, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomek, S.E.; Stegmann, G.M.; Leyrer-Jackson, J.M.; Pińa, J.; Olive, M.F. Restoration of prosocial behavior in rats after heroin self-administration via chemogenetic activation of the anterior insular cortex. Soc. Neurosci. 2020, 15, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Suemitsu, S.; Murakami, S.; Kitamura, N.; Wani, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Ishihara, T. Rescue-like behaviour in mice is mediated by their interest in the restraint tool. Sci. Rep. 2019b, 9, 10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.P.; Silberberg, A.; Casey, A.H.; Kearns, D.N.; Slotnick, B. Does a rat release a soaked conspecific due to empathy? Anim. Cogn. 2017, 20, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, F.; Dzik, V.; Freidin, E.; Damián, J.P.; Casanave, E.B.; Bentosela, M. Do dogs rescue their owners from a stressful situation? A behavioral and physiological assessment. Anim. Cognit. 2020, 23, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bourg, J.; Patterson, J.E.; Wynn, C.D.L. Pet dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) release their trapped and distressed owners: individual variation and evidence of emotional contagion. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amati, S.; Babweteera, F.; Wittig, R.M. Snare removal by a chimpanzee of the Sonso community, Budongo Forest (Uganda). Pan Afr. News 2008, 15, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuyama, N.; Emikey, B.; Bafike, B.; Isolumbo, B.; Iyokango, B.; Mulavwa, M.N.; Furuichi, T. Bonobos apparently search for a lost member injured by a snare. Primates 2012, 53, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.A.; Lee, P.C.; Njiraini, N.; Poole, J.H.; Sayialel, K.; Sayialel, S.; Moss, C. J.; Byrne, R.W. 2008. Do elephants show empathy? J. Conscious Stud.2008, 15, 204-225. Available online: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/jcs/2008/00000015/f0020010/art00008.

- Dittus, W.P.; Ratnayeke, S. Individual and social behavioral responses to injury in wild toque macaques (Macaca sinica). Int. J. Primatol. 1989, 10, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverdes, F. Social life in the animal world; Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co: London, Great Britain, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Siebenaler, J.B.; Caldwell, D.K. Cooperation among adult dolphins. J. Mammal. 1956, 37, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smuts, B.B. Sex and friendship in baboons; Aldine Publishing Co: Hawthorne, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyi, M.Y.; Tung, J.; Jeneby, M.; Patel, N.B.; Altmann, J.; Alberts, S.C. Role of grooming in reducing tick load in wild baboons (Papio cynocephalus). Anim. Behav. 2013, 85, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takanaka, I.; Takefushi, H. Elimination of external parasites (lice) is the primary function of grooming in free-ranging Japanese macaques. Anthropol. Sci. 1993, 101, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A. Reciprocal allogrooming in impala, Aepyceros melampus. Anim. Behav. 1992, 44, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammers, M.; Brouwer, L. Rescue behaviour in a social bird: removal of sticky ‘bird-catcher tree’ seeds by group members. Behaviour 2017, 154, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampton, J.; Frère, C.H.; Potvin, D.A. Australian magpies Gymnorhina tibicen cooperate to remove tracking devices. Aust. Field Ornithol. 2022, 39, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesch, C. The effects of leopard predation on grouping patterns in forest chimpanzees. Behaviour 1991, 117, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, N.S.; Huck, M.; Heymann, E.W. Boa constrictor attack and successful group defence in moustached tamarins, Saguinus mystax. Folia Primatol. 2002, 73, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.; Manson, J.H.; Dower, G.; Wikberg, E. White-faced Capuchins cooperate to rescue a groupmate from a boa constrictor. Folia Primatol. 2003, 74, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberle, M.; Kappeler, P.M. Mutualism, reciprocity, or kin selection? Cooperative rescue of a conspecific from a boa in a nocturnal solitary forager the gray mouse lemur. Am. J. Primatol. 2008, 70, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, C.J.; Radolalaina, P.; Rajerison, M.; Greene, H.W. Cooperative rescue and predator fatality involving a group-living strepsirrhine, Coquerel’s sifaka (Propithecus coquereli), and a Madagascar ground boa (Acrantophis madagascariensis). Primates 2015, 56, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, D.S.; dos Santos, E.; Leal, S.G.; de Jesus, A.K.; Vargas, W.P.; Dutra, I.; Barros, M. Fatal attack on black-tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix penicillata) by a Boa constrictor: a simultaneous assault on two juvenile monkeys. Primates 2016, 57, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, K.M.; Brown, M.R.; Buehler, M.S.; Cheves Hernadez, S.; Ferrero Marín, N.; Kulick, N.K.; Lieber, S.E. Cooperative rescue of a juvenile capuchin (Cebus imitator) from a Boa constrictor. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.R.; Fuentes-Jiménez, A. Rescue behavior in white-faced capuchin monkeys during an intergroup attack: support for the infanticide avoidance hypothesis. Am. J. Primatol. 2006, 68, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzec, A.M.; Kunz, J.; Falkner, S.; Atmoko, S.S.; Utami, A.; Alavi, S.E.; Moldawer, A.M.; Vogel, E.R.; Schuppli, C.; van Schaik, C.P.; van Noordwijk, M.A. The dark side of the red ape: male-mediated lethal female competition in Bornean orangutans. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2016, 70, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, R.L.; Deecke, V.B.; Gabriele, C.M.; Srinivasan, M.; Denkinger, J.; Durban, J.W.; Matthews, E.A.; Matkin, D.R.; Neilson, J.L.; Schulman-Janiger, A.; Shearwater, D.; Stap, P.; Ternullo, R. Humpback whales interfering when mammal-eating killer whales attack other species: mobbing behavior and interspecific altruism? Mar. Mam. Sci. 2017, 33, 7–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belt, T. The naturalist in Nicaragua; Murray: London, Great Britain, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbock, J. Ants, bees and wasps: a record of observations on the habits of the social Hymenoptera. Kegan Paul: London, Great Britain, 1882.

- Frank, E.T.; Schmitt, T.; Hovestadt, T.; Mitesser, O.; Stiegler, J.; Linsenmairs, K.E. Saving the injured: rescue behavior in the termite-hunting ant Megaponera analis. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e160218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.T.; Wehrhahn, M.; Linsenmair, K.E. Wound treatment and selective help in a termite-hunting ant. Proc. Royal Soc. B 2018, 285, 20172457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, W.M. Ants: their structure, development and behavior; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Lafleur, L.J. 1940. Helpfulness in ants. J. Comp. Psychol. 1940, 30, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. A chemical releaser of alarm and digging behavior in the ant Pogonomyrmex badius (Latreille). Psyche 1958, 65, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, H.F. Three problems in invertebrate behavior. II. The digging out of trapped or buried ants by other workers. Ph. D. Thesis, Rutgers University, New Jersey, USA, 1963.

- Markl, H. Stridulation in leaf-cutting ants. Science 1965, 149, 1392–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.S.; Warter, S.L. Chemical releasers of social behavior. Part VII. The isolation of 2-heptanone from Conomyrma pyramica (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) and its modus operandi as a releaser of alarm and digging behavior. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am, 1966; 59, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, H.G. Stimuli releasing digging behavior in the western harvester ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae. J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 1968; 41, 318–323, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25083715. [Google Scholar]

- Hangartner, W. Carbon dioxide, a releaser for digging behavior in Solenopsis geminata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche 1969, 76, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurk, D.J.; Prost, J.; Eisenbraun, E.J. Volatile compounds in ants. Identification of 4-methyl-3-heptanone from Pogonomyrmex ants. J. Insect Physiol. 1966, 12, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschwitz, U.; Mühlenberg, M. Zur Jagdstrategie einiger orientalischer Leptogenys-Arten (Formicidae, Ponerinae). Oecologia 1975, 30, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Visvader, A.; Nowbahari, E.; Hollis, K.L. Precision rescue behavior in North American ants. Evol. Psychol. 2013, 11, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miler, K. Moribund ants do not call for help. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0151925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miler, K.; Yahya, B.E.; Czarnoleski, M. Pro-social behaviour of ants depends on their ecological niche - Rescue actions in species from tropical and temperate regions. Behav. Processes 2017a, 144, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miler, K.; Symonowicz, B.; Godzińska, E.J. Increased risk proneness or social withdrawal? The effects of shortened life expectancy on the expression of rescue behavior in workers of the ant Formica cinerea (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Insect Behav. 2017b, 30, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turza, F.; Zuber, G.; Bzoma, M.; Prus, M.; Filipiak, M.; Miler, K. Ants co-occurring with predatory antlions show unsuccessful rescue behavior towards captured nestmates. J. Insect Behav. 2020, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowbahari, E.; Hollis, K.L.; Durand, J.-L. Division of labor regulates precision rescue behavior in sand dwelling Cataglyphis cursor ants: to give is to receive. PLoS One 2012, 7, e48516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowbahari, E.; Amirault, C.; Hollis, K.L. 2016a. Rescue of newborn ants by older Cataglyphis cursor adult workers. Anim. Cogn. 2016a, 19, 43–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowbahari, E.; Hollis, K.L.; Bey, M.; Demora, L.; Durand, J.-L. Rescue specialists in Cataglyphis piliscapa ants: the nature and development of ant first responders. Learn. Behav. 2022, 50, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, K.L.; Nowbahari, E. A comparative analysis of precision rescue behaviour in sand-dwelling ants. Anim. Behav. 2013a, 85, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhoo, T.; Durand, J.-L.; Hollis, K.L.; Nowbahari, E. Organization of rescue behaviour sequences in ants, Cataglyphis cursor, reflects goal-directedness, plasticity and memory. Behav. Processes 2017, 139, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, P. J.; Zwoińska, M.; Siedlecki, I.; Malinowska, K.; Korczyńska, J.; Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J. Trapped, but not helpless? How workers of Formica cinerea and Formica fusca rescue their trapped nestmates. In 7th Central European Workshop of Myrmecology, Cracow, Poland, 21–24 April 2017, Abstract Book; 2017.

- Miler, K.; Kuszewska, K. Secretions of mandibular glands are not involved in the elicitation of rescue behaviour in Formica cinerea ants. Insectes Soc. 2017, 64, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uy, F.M.K.; Adcock, J.D.; Jeffries, S.F.; Pepere, E. Intercolony distance predicts the decision to rescue or attack conspecifics in weaver ants. Insectes Soc. 2019, 66, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andras, J.P.; Hollis, K.L.; Carter, K.A.; Couldwell, G.; Nowbahari, E. Analysis of ants' rescue behavior reveals heritable specialization for first responders. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223, jeb212530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Junior, L.C.; Silva, E.P.; Antonialli-Junior, W.F. Do Odontomachus brunneus nestmates request help and are taken care of when caught? Sociobiology 2021, 68, e6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turza, F.; Miler, K. Comparative analysis of experimental testing procedures for the elicitation of rescue actions in ants. Curr. Zool. 2022, 68, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turza, F.; Miler, K. Injury shortens life expectancy in ants and affects some risk-relate decisions of workers. Anim. Cogn. 2023a, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turza, F.; Miler, K. Small workers are more persistent when providing and requiring help in a monomorphic ant. Sci. Rep. 2023b, 13, 21580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, A.; Gilad, T.; Massad, D.; Ferber, A.; Ben-Ezra, D.; Segal, D.; Foitzik, S.; Scharf, I. Foraging is prioritized over nestmate rescue in desert ants and pupae are rescued more than adults. Behav. Ecol. 2023, 34, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapich, C.L.; Hölldobler, B. Destruction of spiderwebs and rescue of ensnared nestmates by a granivorous desert ant (Veromessor pergandei). Am. Nat. 2019, 194, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elżanowski, A.; Czechowski, W. 2015. Lasius niger (L.) ants invade the web of an agelenid spider. Pol. J. Ecol. 2015, 63, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, K.L. Ants and antlions: The impact of ecology, coevolution and learning on an insect predator-prey relationship. Behav. Processses 2017, 139, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittka, L. , Rossi, N. Social cognition in insects. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaczkes, T. J. Advanced cognition in ants. Myrmecol. News 2022, 32, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poissonnier, L.-A.; Tait, C.; Lihoreau, M. What is really social about social insect cognition? Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 10, 1001045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Frisch, K. The dance language and orientation of honeybees. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967.

- Barron, A.B.; Plath, J.A. The evolution of honey bee dance communication: a mechanistic perspective. J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 220, 4339–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbetts, E.A. Visual signals of individual identity in the wasp Polistes fuscatus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2002, 269, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibbetts, E.A. , Desjardins, E., Kou, N., Wellman, L. Social isolation prevents the development of individual face recognition in paper wasps. Anim. Behav. 2019, 152, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbetts, E.A.; Wong, E.; Bonello, S. Wasps use social eavesdropping to learn about individual rivals. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 3007–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alem, S.; Perry, C.J.; Zhu, X.; Loukola, O.J.; Ingraham,T. ; Søvik, E.; Chittka, L. Associative mechanisms allow for social learning and cultural transmission of string pulling in an insect. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukola, O.J.; Solvi, C.; Coscos, L.; Chittka, L. Bumblebees show cognitive flexibility by improving on an observed complex behavior. Science 2017, 355, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. The ants; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtusiak, J.; Godzińska, E.J.; Déjean, A. Capture and retrieval of very large prey by workers of the African weaver ant, Oecophylla longinoda (Latreille 1802). Trop. Zool. 1995, 8, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaczkes, T.J.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Cooperative transport in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and elsewhere. Myrmecol. News 2013, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ettorre, P.; Heinze, J. Individual recognition in ant queens. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2170–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrill, W.L. Tool using behavior of Pogonomyrmex badius (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Fla. Entomol. 1972, 55, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellers, J.H.; Fellers, G.M. Tool use in a social insect and its implications for competitive interactions. Science 1976, 192, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maák, I. , Roelandt, G., d'Ettorre, P. A small number of workers with specific personality traits perform tool use in ants. Elife 2020, 9, e61298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittlinger, M.; Wehner, R.; Wolf, H. The ant odometer: stepping on stilts and stumps. Science 2006, 312, 1965–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, K.L.; McNewa, K.; Sosa, T.; Harrsch, F.A.; Nowbahari, E. Natural aversive learning in Tetramorium ants reveals ability to form a generalizable memory of predators’ pit traps. Behav. Processes 2017, 139, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, N.; Richardson, T. Teaching in tandem-running ants. Nature 2006, 439, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Danczak, L.; Thompson, B.; Morshed, T.; Pratt, S.C. Route learning during tandem running in the rock ant Temnothorax albipennis. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 15, jeb221408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, K.L.; Harrsch, F.A.; Nowbahari, E. Ants vs. antlions: an insect model for studying the role of learned and hardwired behavior in coevolution. Learn. Motiv. 2015, 50, 68–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, W.; Radchenko, A.; Czechowska, W.; Vepsäläinen, K. The ants of Poland with reference to the myrmecofauna of Europe. Fauna Poloniae Vol. 4 New Series; Natura Optima Dux Foundation: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann, K. 1975. Zur Regulation des Beuteeintrags bei Waldameisen (Formica polyctena). Oecologia 1975, 22, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Véle, A.; Modlinger, R. Foraging strategy and food preference of Formica polyctena ants in different habitats and possibilities for their use in forest protection. Lesn. Cas. For. J. 2016, 62, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos-Peral, G.; Juhász, O.; Kiss, P.J.; Módra, G.; Tenyér, A.; Maák, I. Wood ants as biological control of the forest pest beetles Ips spp. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabelis, A.A. Wood ant wars. The relationship between aggression and predation in the red wood ant (Formica polyctena Foerst.). Neth. J. Zool. 1979, 29, 451–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J. The effect of past and present group size on responses to prey in the ant Formica polyctena Först. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 1997, 57, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J. Group size: an important factor controlling the expression of predatory behaviour in workers of the wood ant Formica polyctena Först. Biol Bull. Poznań 2000, 37, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J. The role of group size in the control of expression of predatory behaviour in workers of the red wood ant Formica polyctena (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 2004a, 43, 295–325. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J. The effect of gradual increase of group size on the expression of predatory behaviour in workers of the red wood ant Formica polyctena (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 2004b, 43, 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J. Effect of chronic oral administration of octopamine on the expression of predatory behavior in small groups of workers of the red wood ant Formica polyctena (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 2008, 52, 703–72. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, A.; Korczyńska, J.; Wnuk, A.; Symonowicz, B.; Gonzalez Szwacka, A.; Mazurkiewicz, P.; Kostowski, W.; Godzińska, E.J. The effects of serotonin, dopamine, octopamine and tyramine on behavior of workers of the ant Formica polyctena during dyadic aggression tests. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2013, 73, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, A.; Kostowski, W.; Korczyńska, J.; Szczuka, A. , Symonowicz, B.; Bieńkowski, P.; Mierzejewski, P.; Godzińska, E.J. Brain GABA and glutamate levels in workers of two ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Interspecific differences and effects of queen presence/absence. Insect Sci. 2014, 21, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczuka, A.; Symonowicz, B.; Korczyńska, J.; Wnuk, A. , Godzińska, E.J. Brood hiding test: a new bioassay for behavioral and neuroethological ant research. Sociobiology 2014, 61, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczyńska, J.; Szczuka, A.; Symonowicz, B.; Wnuk, A.; Gonzalez Szwacka, A.; Mazurkiewicz, P.J.; Studnicki, M.; Godzińska, E.J. The effects of age and past and present behavioral specialization on behavior of workers of the red wood ant Formica polyctena Först. during nestmate reunion test. Behav. Processes 2014, 107, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, G. Response to movement by Formica polyctena Forst. Nature 1963, 99, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, R. Foraging strategy of wood ants (Formica rufa group). I: Age polyethism and topographic traditions. Acta Zool. Fenn. 1977a, 149, 1-30.

- Rosengren, R. Foraging strategy of wood ants (Formica rufa group). II: Nocturnal orientation and diel periodicity. Acta Zool. Fenn. 1977b, 150, 1-30.

- Symonowicz, B.; Kieruzel, M.; Szczuka, A.; Korczyńska, J.; Wnuk, A.; Mazurkiewicz, P.J.; Chiliński, M.; Godzińska, E.J. Behavioral reversion and dark-light choice behavior in workers of the red wood ant Formica polyctena. J. Insect Behav. 2015, 28, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczuka, A.; Godzińska, E.J.; Korczyńska, J. Factors mediating ant social behavior: interplay of neuromodulation and social context. Kosmos 2019, 68, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forel, A. Les fourmis de la Suisse; Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles: Zurich, Switzerland, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, D. Über die Arbeitstteilung im Staate von Formica rufa rufo-pratensis minor Gössw. und ihre verhaltensphysiologischen Grundlagen: ein Beitrag zur Biologie der Roten Waldameise. Wiss. Abh. dt. Akad. Landw.-Wiss. Berl. 1958, 30, 1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzańska, J. Studies on the division of labour in ants genus Formica. Acta Biol. Exp. 1959, 19, 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mersch, D.P.; Crespi, A.; Keller, L. Tracking individuals shows spatial fidelity is a key regulator of ant social organization. Science 2013, 31, 1090–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzański, J. Contribution to the ethology of Leptothorax acervorum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Acta Biol. Exp. (Warsz) 1966, 26, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Provost, E. Une nouvelle méthode de marquage permettant l'identification des membres d'une société de fourmis. Insectes Soc. 1983, 30, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, J.; Peeters, C.; Hölldobler, B. H. Worker policing limits the number of reproductives in a ponerine ant. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1999, 266, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn-Mrozowska, E. Energy budget elements of an experimental nest of Formica pratensis Retzius 1783 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Pol. Ecol. Stud. 1976, 2, 55–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren, R.; Fortelius, W. Trail communication and directional recruitment of food in red wood ants (Formica). Ann. Zool. Fenn. 1987, 24, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Oi, D.H.; Pereira, R.M. Ant behavior and microbial pathogens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Fla. Entomol. 1993, 76, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.O.H.; Eilenberg, J.; Boomsma, J.J. Trade-offs in group living: transmission and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2002, 269, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.O.H.; Boomsma, J.J. Genetic diversity and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ant societies. Evolution 2004, 58, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, S.; Armitage, S.A.O. , Schmid-Hempel, P. Social immunity. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, S.; Pull, C.D.; Fürst, M.A. Social immunity: emergence and evolution of colony-level disease protection. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugelvig, L.V.; Cremer, S. Social prophylaxis: group interaction promotes collective immunity in ant colonies. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1967–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.N.; Hughes, W.O.H. Adaptive social immunity in leaf-cutting ants. Biol. Lett. 2009, 23, 446–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugelvig, L.V.; Kronauer, D.J.; Schrempf, A.; Heinze, J.; Cremer, S. Rapid anti-pathogen response in ant societies relies on high genetic diversity. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 2821–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, N.; Lefèvre, T.; Jensen, A.B.; D’Ettorre, P. Sick ants become unsociable. J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 25, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, A.; Purcell, J.; Buechel, S.D.; Buri, P.; Chapuisat, M. The expression and impact of antifungal grooming in ants. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 24, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, M.; Vyleta, M.L.; Theis, F.J.; Stock, M.; Tragust, S.; Klatt, M.; Drescher, V.; Marr, C.; Ugelvig, L.V.; Cremer, S. Social transfer of pathogenic fungus promotes active immunisation in ant colonies. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, M.; Pull, C.D.; Metzler, S.; Seif, K.; Naderlinger, E.; Grasse, A.V.; Cremer, S. Ants avoid superinfections by performing risk-adjusted sanitary care. PNAS 2018, 115, 2782–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuno, M.; Tsuji, K.; Sato, H.; Fujisaki, K. Plasticity of grooming behavior against entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae in the ant Lasius japonicus. J Ethol. 2012, 30, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragust, S.; Mitteregger, B.; Barone, V.; Konrad, M.; Ugelvig, L.V.; Cremer, S. Ants disinfect fungus-exposed brood by oral uptake and spread of their poison. Curr. Biol. 2013a, 23, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragust, S.; Ugelvig, L.V.; Chapuisat, M.; Heinze, J.; Cremer, S. Pupal cocoons affect sanitary brood care and limit fungal infections in ant colonies. BMC Evol. Biol. 2013b, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yek, S.H.; Schiøtt, M.; Boomsma, J.J. Differential gene expression in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants after challenges with two fungal pathogens. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 2173–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhukovskaya, M.; Yanagawa, A.; Forschler, B.T. Grooming behavior as a mechanism of insect disease defense. Insects 2013, 4, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csata, E.; Bernadou, A.; Rákosy-Tican, E.; Heinze, J.; Markó, B. The effects of fungal infection and physiological condition on the locomotory behaviour of the ant Myrmica scabrinodis. J. Insect Physiol. 2017, 98, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhus, C.; Ugelvig, L.V.; Tourdot, E.; Heinze, J.; Doums, C.; Cremer, S. Increased grooming after repeated brood care provides sanitary benefits in a clonal ant. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2014, 68, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranter, C.; Hughes, W.O.H. Acid, silk and grooming: alternative strategies in social immunity in ants? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2015, 69, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranter, C.; LeFevre, L.; Evison, S.E.T.; Hughes, W.O.H. Threat detection: Contextual recognition and response to parasites by ants. Behav. Ecol. 2015, 26, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, J.B.; Detrain, C. Ants detect but do not discriminate diseased workers within their nest. Naturwissenschaften 2016, 103, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, B.M.; Miller, R.W.; Vinson, S.B.; Georgis, R. Susceptibility and behavioral response of red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) to selected entomogenous nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae & Heterorhabditidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1992, 85, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, I.; Modlmeier, A.P.; Beros, S.; Foitzik, S. Ant societies buffer individual-level effects of parasite infections. Am. Nat. 2012, 180, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, R.D.S.; Puccini, C.; Forti, L. C.; de Matos, C.A.O. Allogrooming, self-grooming, and touching behavior: contamination routes of leaf-cutting ant workers using a fat-soluble tracer dye. Insects 2017, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, A.; Richard, F.J. Social management of LPS-induced inflammation in Formica polyctena ants. Brain Behav. Immun. 2008, 22, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chameron, S.; Schatz, B.; Pastergue-Ruiz, I.; Beugnon, G.; Collett, T.S. The learning of a sequence of visual patterns by the ant Cataglyphis cursor. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, N.; Guerrieri, F.J.; d’Ettorre, P. (2010). Significance of chemical recognition cues is context dependent in ants. Anim. Behav. 2010, 80, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, N.F.; Hölldobler, B.; Gladstein, D.S. The kin recognition system of carpenter ants Camponotus spp. iii. Within colony discrimination. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1987, 20, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | WL- ants | WL+ ants | Z | p |

| Median | 1 | 15 |

-5.18 |

< 0.001 |

| Quartiles | 1-1 | 5-39 | ||

| Range | 1-8 | 1-75 |

| |||||

| Variable | Measure | Leg (L) | Petiole (P) | Z | p |

|

Latency [%] |

Median | 59.17 | 64.66 | -0.20 | 0.838 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 24.38-100.00 | 17.17-100.00 | |||

| Range | 3.44-100.00 | 3.32-100.00 | |||

|

Number of episodes |

Median | 1 | 1 | -1.02 | 0.309 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 0-5 | 0-3 | |||

| Range | 0-17 | 0-14 | |||

|

Total duration [s] |

Median | 7.76 | 3.34 | -1.46 | 0.144 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 0-34.21 | 0-21.89 | |||

| Range | 0-171.00 | 0-331.24 | |||

| |||||

| Variable | Measure | Leg (LI) (immobile) |

Petiole (P) | Z | p |

| Latency [%] | Median | 67.02 | 60.07 | -0.56 | 0.578 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 24.61-100.00 | 16.29-100.00 | |||

| Range | 3.44-100.00 | 3.32-100.00 | |||

| Number of episodes | Median | 1 | 1 | -0.53 | 0.595 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 0-5 | 0-3 | |||

| Range | 0-17 | 0-14 | |||

| Total duration [s] |

Median | 10.50 | 3.48 | -1.24 | 0.215 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 0-37.77 | 0-25.48 | |||

| Range | 0-171.00 | 0-331.24 | |||

| Ant | Subcategory | RL | RLM | First episode of rescue behaviour |

| 5b | L | 1 | 1 | B |

| 17v | L | 2 | 1* | B |

| 18v | L | 1 | 1 | B |

| 4g | L+P | 7 | 1 | B |

| 6y | L+P | 17 | 3 ** | P |

| 14g | L+P | 1 | 1 | P |

| Variable | Measure | Leg (L) | Petiole (P) | Z | p |

| Length of the accessible part of the wire loop [mm] |

Median | 3.3 | 3.5 |

-1.31 |

0.191 (NS) |

| Quartiles | 2.6-3.7 | 3.0-3.8 | |||

| Range | 2.2-5.5 | 2.0-5.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).