Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

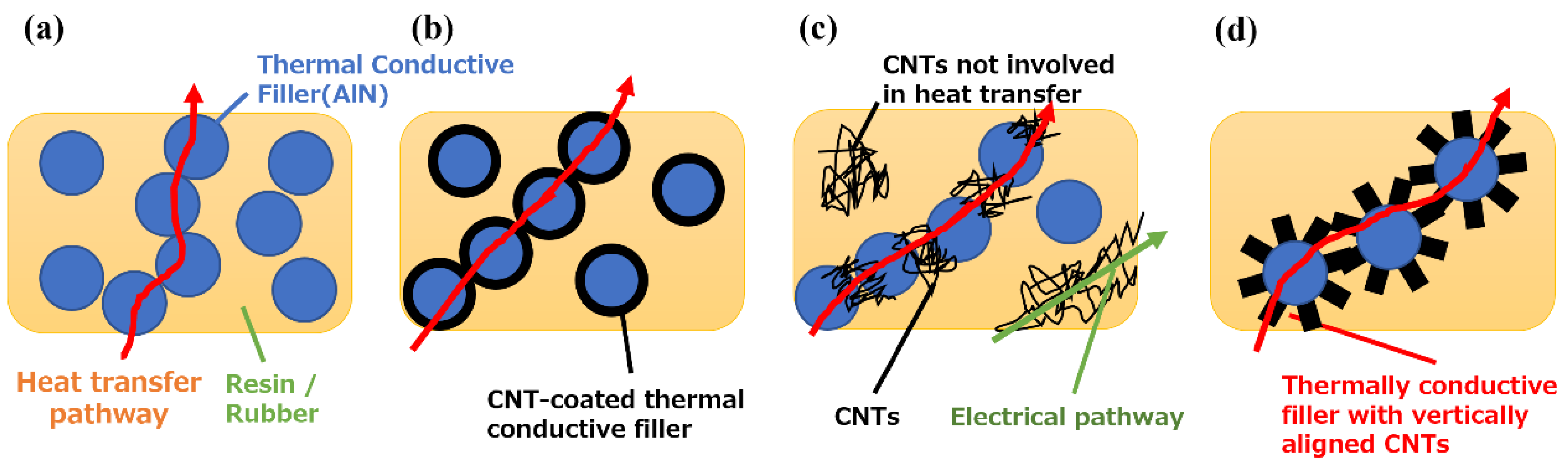

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

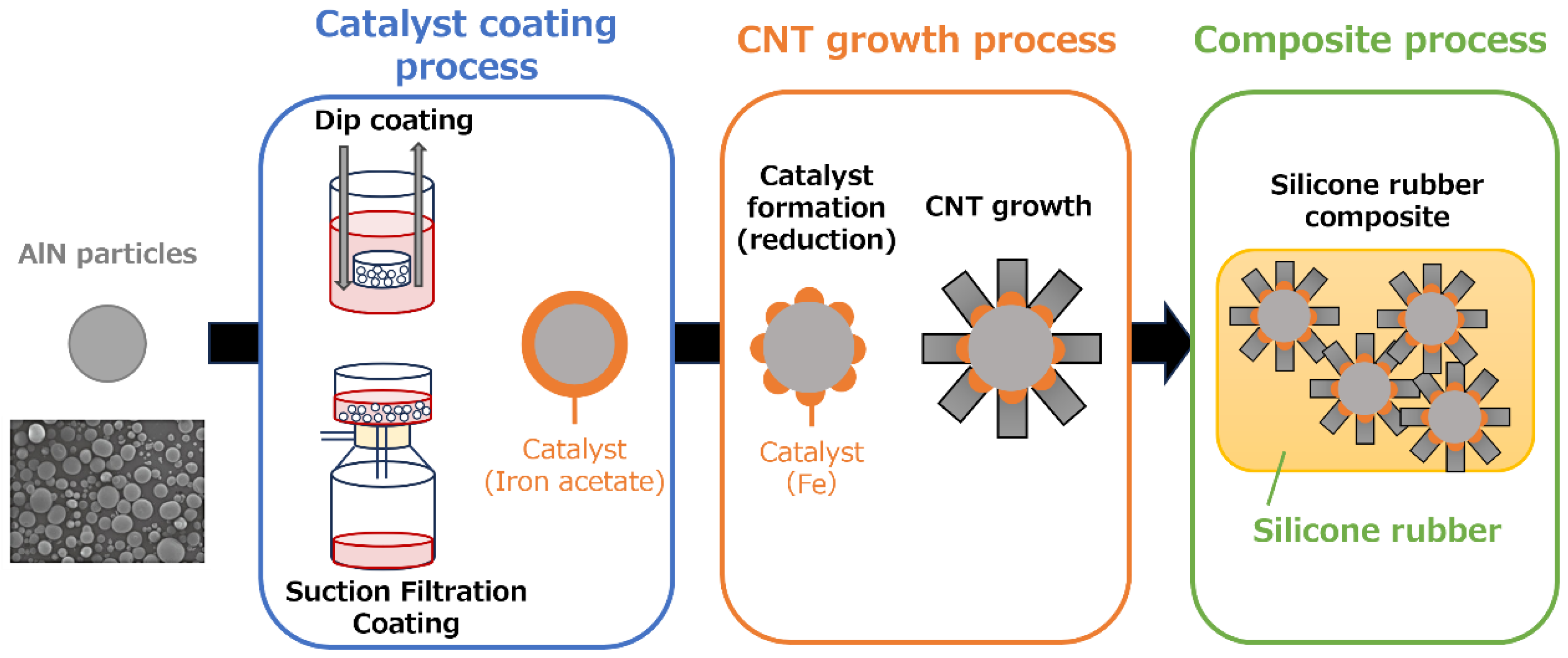

2.1. Coating of Fe catalyst onto AlN particles

2.2. Synthesis of vertically aligned CNTs on Fe/AlN particles

2.3. Preparation of CNT/AlN/silicone rubber nanocomposites

2.4. Characterizations

3. Results and discussion

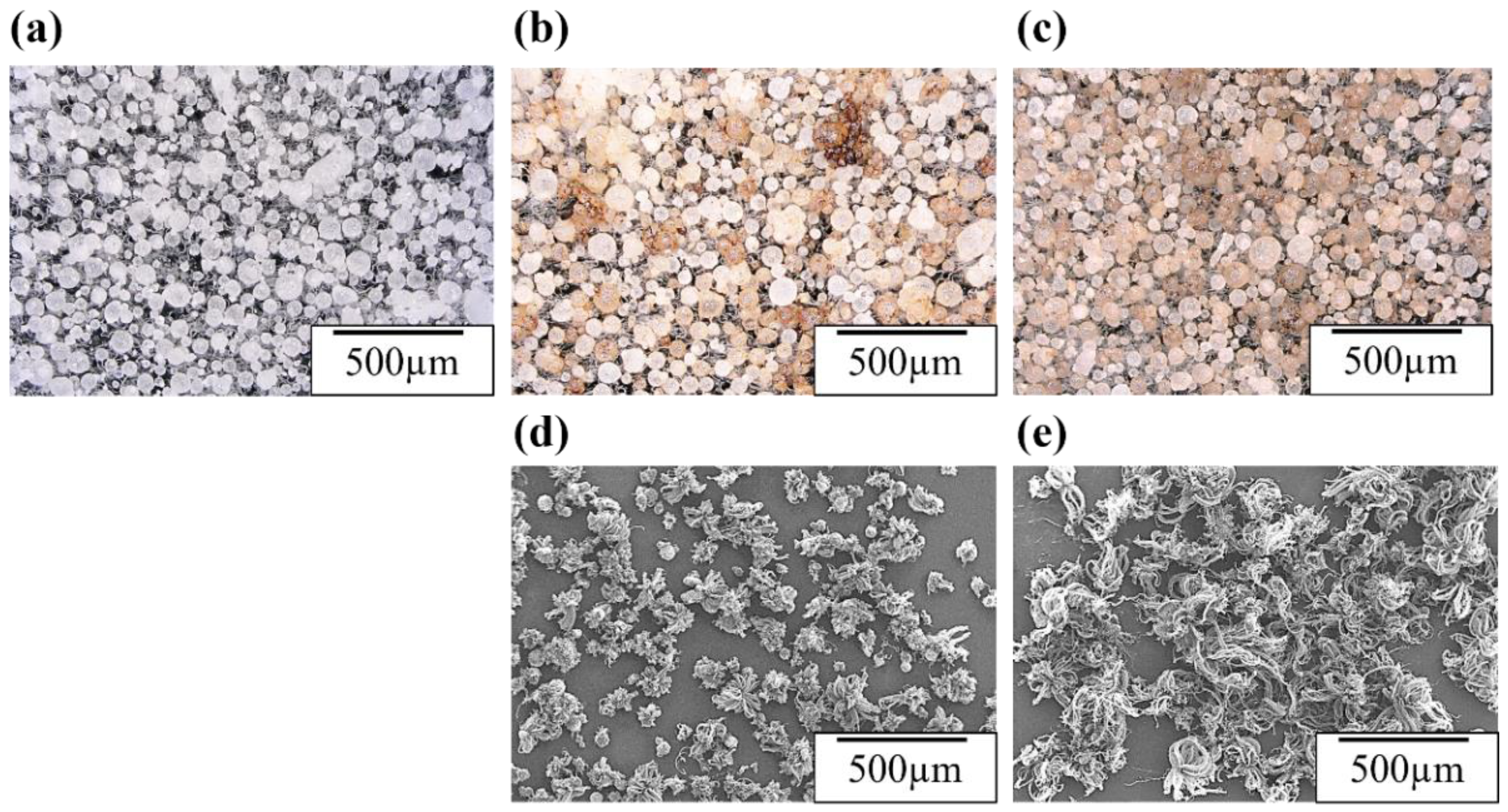

3.1. Coating of Fe catalyst on AlN particles

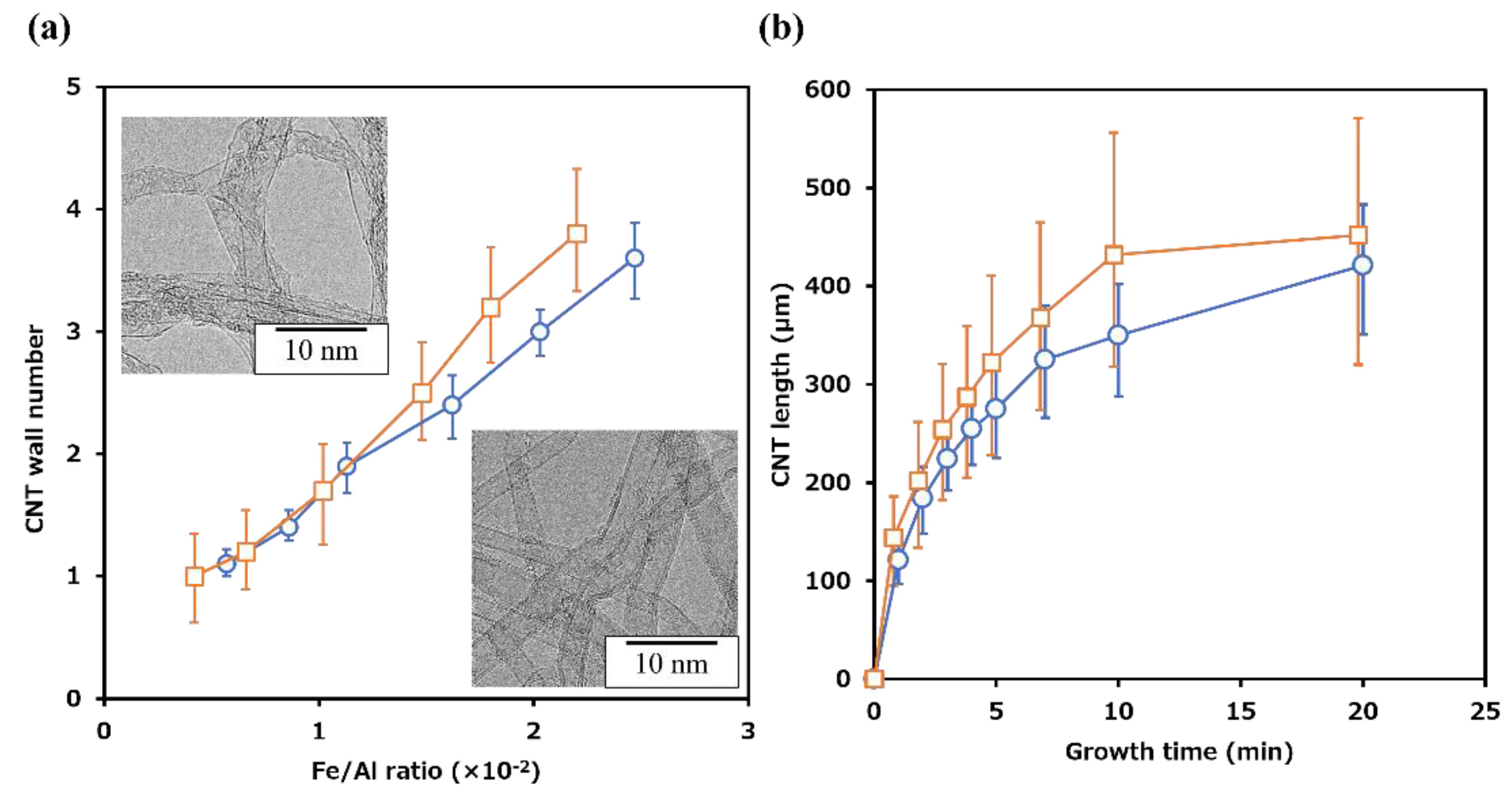

3.2. Control of CNT growth on AlN particles

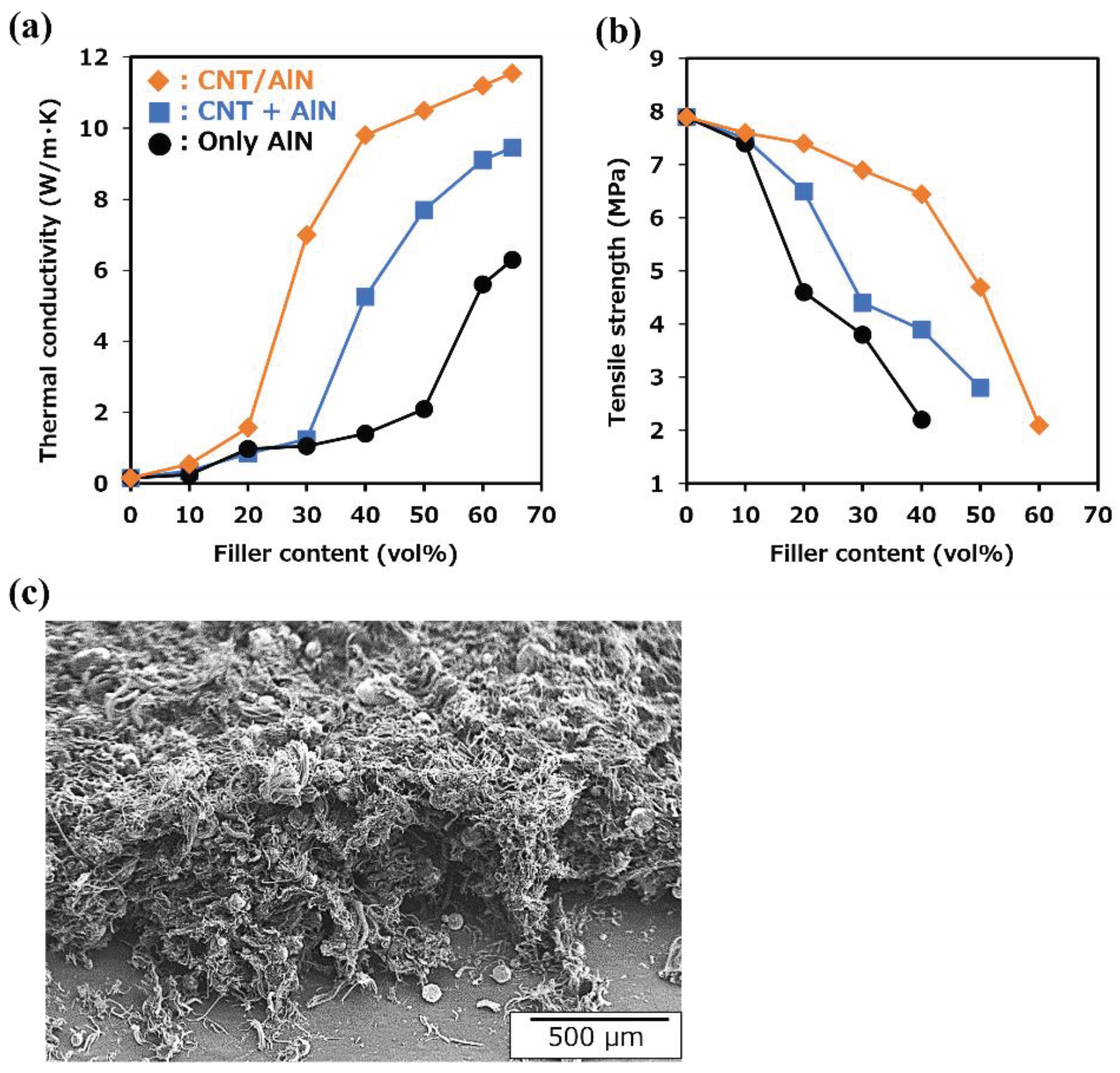

3.3. Thermal properties of CNT/AlN/Slicon rubber composites

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Chen, K.; Hong, S.; Lai, Y. A critical review of battery thermal performance and liquid based battery thermal management. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Cao, L.; Bi, G. A review on battery thermal management in electric vehicle application. J. Power Sources 2017, 367, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.P.; Yang, L.Y.; Yang, J.; Bai, L.; Bao, R.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Yang, M.B.; Lan, H.B.; Yang, W. Recent advances in polymer-based thermal interface materials for thermal management: A mini-review. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Xu, Y.; Song, C.; Deng, T. Recent Advances in Thermal Interface Materials for Thermal Management of High-Power Electronics. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, M.; Ren, S.B. Review of metal matrix composites with high thermal conductivity for thermal management applications. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2011, 21, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, K.; Shi, X.; Guo, Y.; Gu, J. Interfacial thermal resistance in thermally conductive polymer composites: A review. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Yu, W. A critical review of the preparation strategies of thermally conductive and electrically insulating polymeric materials and their applications in heat dissipation of electronic devices. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 2023, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, M.; Hu, Y. Emerging interface materials for electronics thermal management: experiments, modeling, and new opportunities. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 10568–10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NematpourKeshteli, A.; Iasiello, M.; Langella, G.; Bianco, N. Enhancing PCMs thermal conductivity: A comparison among porous metal foams, nanoparticles and finned surfaces in triplex tube heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 212, 118623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renteria, J.D.; Nika, D.L.; Balandin, A.A. Graphene Thermal Properties: Applications in Thermal Management and Energy Storage. Appl. Sci. 2014, 4, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xian, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ji, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L. Construction of interconnected Al2O3 doped rGO network in natural rubber nanocomposites to achieve significant thermal conductivity and mechanical strength enhancement. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 186, 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, X.; Ding, F.; Bai, L.; Yuan, F. Simultaneously enhance thermal conductive property and mechanical properties of silicon rubber composites by introducing ultrafine Al2O3 nanospheres prepared via thermal plasma. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 190, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojny, F.H.; Wichmann, M.H.; Fiedler, B.; Kinloch, I.A.; Bauhofer, W.; Windle, A.H.; Schulte, K. Evaluation and Identification of Electrical and Thermal Conduction Mechanisms in Carbon Nanotube/Epoxy Composites. Polymer 2006, 47, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.M.; Gund, V.; Calaza, N.K.; Vinayakumar, K. Piezoelectric aluminum nitride thin films: A review of wet and dry etching techniques. Microelectron Eng. 2022, 257, 111753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Wu, J.; Cheng, H.M.; Kang, F. Two-Dimensional Materials for Thermal Management Applications. Joule 2018, 2, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Hirosaki, N. Electric current assisted sintering of AlN ceramics: thermal conductivity and transparency. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2014, 113, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.J.; Gawlytta, R.; Fromm, A.; Klose, C. Increasing thermal conductivity in aluminium-copper compound castings: modelling and experiments. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Bae, K.M.; An, K.H.; Park, S.J. Effects of surface nitrification on thermal conductivity of modified aluminum oxide nanofibers-reinforced epoxy matrix nanocomposites. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2012, 33, 3258–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdulKarim-Talaq, M.; Hassan, K.T.; Hameed, D.A. Improvement of thermal conductivity of novel asymmetric dimeric coumarin liquid crystal by doping with boron nitride and aluminium oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 297, 127367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Hou, G.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Wang, X. New gutta percha composite with high thermal conductivity and low shear viscosity contributed by the bridging fillers containing ZnO and CNTs. Compos. B. Eng. 2019, 173, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Lee, S.M.; Shanefield, D.J.; Cannon, W.R. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Polymer Matrix Composite via High Solids Loading of Aluminum Nitride in Epoxy Resin. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 1169–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.T.; Sukachonmakul, T.; Kuo, M.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Wattanakul, K. Surface modification of aluminum nitride by polysilazane and its polymer-derived amorphous silicon oxycarbide ceramic for the enhancement of thermal conductivity in silicone rubber composite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 292, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasher, R. Thermal Interface Materials: Historical Perspective, Status, and Future Directions. Proc. IEEE Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2006, 94, 1571–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.Z.; Xua, J.Z.; Peng, J.J.; Kanga, F.Y.; Dua, H.D.; Lia, J.; Chiang, S.W.; Xu, C.J.; Hu, N.; Ning, X.S. Experimental and theoretical studies of effective thermal conductivity of composites made of silicone rubber and Al2O3 particles. Thermochimica Acta 2014, 614, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hyuga, H.; Kusano, D.; Yoshizawa, Y.; Hirao, K. A Tough Silicon Nitride Ceramic with High Thermal Conductivity. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4563–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Choi, D.K.; Yeo, D.H.; Shin, H.S.; Yoon, H.G. Influence of ball milling contamination on properties of sintered AlN substrates. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 5349–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Fan, X.; Lin, J.; Wang, G.; Yan, Q.; Yu, T.; Ajayan, P.M.; Tour, J.M. High thermal conductivity of suspended few-layer hexagonal boron nitride sheets. Nano Res. 2014, 7, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, C.J.; Muhich, C.L.; Weimer, A.W.; Musgrave, C.B. Aluminum Nitride Hydrolysis Enabled by Hydroxyl-Mediated Surface Proton Hopping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18550–18559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, M.; Kawakami, S.; Yokagawa, Y. Spherical Aluminum Nitride Fillers for Heat-Conducting Plastic Packages. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 88, 2615–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, L.; Kido, T.; Xi, G.; Xu, G.; Guo, F. Thermal and insulating properties of epoxy/aluminum nitride composites used for thermal interface material. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocjan, A.; Dakskobler, A.; Krnel, K.; Kosmac, T. The course of the hydrolysis and the reaction kinetics of AlN powder in diluted aqueous suspensions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Yu, Y.L.; Yang, H.; Wu, Y.Y.; Zhong, M.F.; Lin, S.M.; Zhang, Z.J.; Xu, W.; Wu, L.G. ; Mechanism for the hydrolysis resistance of aluminum nitride powder modified by boric acid. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 32696–32702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binner, J.; Zhang, Y. ; Surface chemistry and hydrolysis of a hydrophobic-treated aluminium nitride powder. Ceram. Int. 2005, 31, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Toole, R.J.; Hill, C.; Buur, P.J.; Bartel, C.J.; Gump, C.J.; Musgrave, C.B.; Weimer, A.W. Hydrolysis protection and sintering of aluminum nitride powders with yttria nanofilms. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 3123–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.H.; Wang, Y.K.; Wang, S.C. Aluminum nitride surface functionalized by polymer derived silicon oxycarbonitride ceramic for anti-hydrolysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 772, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, F.; Li, X.; Shi, D.; Xue, Z.; Xie, X. Construction of 3D boron nitride nanosheets/silver networks in epoxy-based composites with high thermal conductivity via in-situ sintering of silver nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.W.; Park, M.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.I.; Yoon, H.G. Enhanced thermal conductivity of polymer composites filled with hybrid filler. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. 2006, 37, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, J. ; Magnetic aligned AlN/epoxy composite for thermal conductivity enhancement at low filler content. Compos. B. Eng. 2016, 93, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J. Thermal conductivity of epoxy composites with a binary-particle system of aluminum oxide and aluminum nitride fillers. Compos. B. Eng. 2013, 51, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaska, K.; Rybak, A.; Kapusta, C.; Sekula, R.; Siwek, A. Enhanced thermal conductivity of epoxy–matrix composites with hybrid fillers. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2015, 26, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Xiong, D. Improved thermal conductivity of epoxy composites using a hybrid multi-walled carbon nanotube/micro-SiC filler. Carbon 2010, 48, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, G.; Yoon, S.F.; Ahn, J.; Wang, S.G.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.Q. Thermal conductivity of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 165440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisala, A.; Li, Q.; Kinloch, I.A.; Windle, A.H. Thermal and electrical conductivity of single- and multi-walled carbon nanotube-epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 1285–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gu, M.; Guo, Y.; Pan, X.; Mu, G. Effects of carbon nanotube functionalization on the mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy composites. Carbon 2009, 47, 1723–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Takai, H.; Sakurai, S.; Futaba, D.N. Millimetre-scale growth of single-wall carbon nanotube forests using an aluminium nitride catalyst underlayer. MRS Adv. 2019, 4, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, K.; Futaba, D.N.; Mizuno, K.; Namai, T.; Yumura, M.; Iijima, S. Water-Assisted Highly Efficient Synthesis of Impurity-Free Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Science 2004, 306, 1362–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Kishi, R.; Kobashi, K.; Morimoto, T.; Okazaki, T.; Yamada, T.; Hata, K. Improved thermal stability of silicone rubber nanocomposites with low filler content, achieved by well-dispersed carbon nanotubes. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclaren, K. XIII. The development of the CIE 1976 (L*a*b*) uniform colour space and colour-difference formula. J. Soc. Dyers. Colour. 1976, 92, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Namai, T.; Hata, K.; Futaba, D.N.; Mizuno, K.; Fan, J.; Yudasaka, M.; Yumura, M.; Iijima, S. Size-selective growth of double-walled carbon nanotube forests from engineered iron catalysts. Nat. Nanotech. 2006, 1, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futaba, D.N.; Hata, K.; Yamada, T.; Mizuno, K.; Yumura, M.; Iijima, S. Kinetics of Water-Assisted Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Synthesis Revealed by a Time-Evolution Analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 056104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Futaba, D.N.; Kimura, H.; Sakurai, S.; Yumura, M.; Hata, K. Absence of an Ideal Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Forest Structure for Thermal and Electrical Conductivities. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10218–10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Futaba, D.N.; Sakurai, S.; Yumura, M.; Hata, K. Interplay of wall number and diameter on the electrical conductivity of carbon nanotube thin films. Carbon 2014, 67, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, S.; Kamada, F.; Futaba, D.N.; Yumura, M.; Hata, K. Influence of lengths of millimeter-scale single-walled carbon nanotube on electrical and mechanical properties of buckypaper. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, S.; Kobashi, K.; Yumura, M.; Hata, K. Mechanically Durable and Highly Conductive Elastomeric Composites from Long Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Mimicking the Chain Structure of Polymers. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 2710–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobashi, K.; Ata, S.; Yamada, T.; Futaba, D.N.; Okazaki, T.; Hata, K. Classification of Commercialized Carbon Nanotubes into Three General Categories as a Guide for Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 4043–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, R.; Inoue, T.; Zheng, Y.; Kumamoto, A.; Qian, Y.; Sato, Y.; Liu, M.; Tang, D.; Gokhale, D.; Guo, J.; Hisama, K.; Yotsumoto, S.; Ogamoto, T.; Arai, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hou, B.; Anisimov, A.; Maruyama, M.; Miyata, Y.; Okada, S.; Chiashi, S.; Li, Y.; Kong, J.; Kauppinen, E.I.; Ikuhara, Y.; Suenaga, K.; Maruyama, S. One-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures. Science 2020, 367, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| a* | b* | L* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | STD | Value | STD | Value | STD | ||

| AlN Beads | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 95.0 | 2.2 | |

| Vacuum | 3 times | 1.6 | 0.85 | 10.3 | 1.6 | 79.3 | 2.4 |

| filtration | 5 times | 3.9 | 1.1 | 15.6 | 1.9 | 77.4 | 2.8 |

| Dip coating | 3.5 | 1.9 | 18.9 | 3.4 | 82.8 | 4.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).