1. Introduction

“How many kilowatts of green electricity offset one less submerged Mesolithic cultural landscape?” [

1]

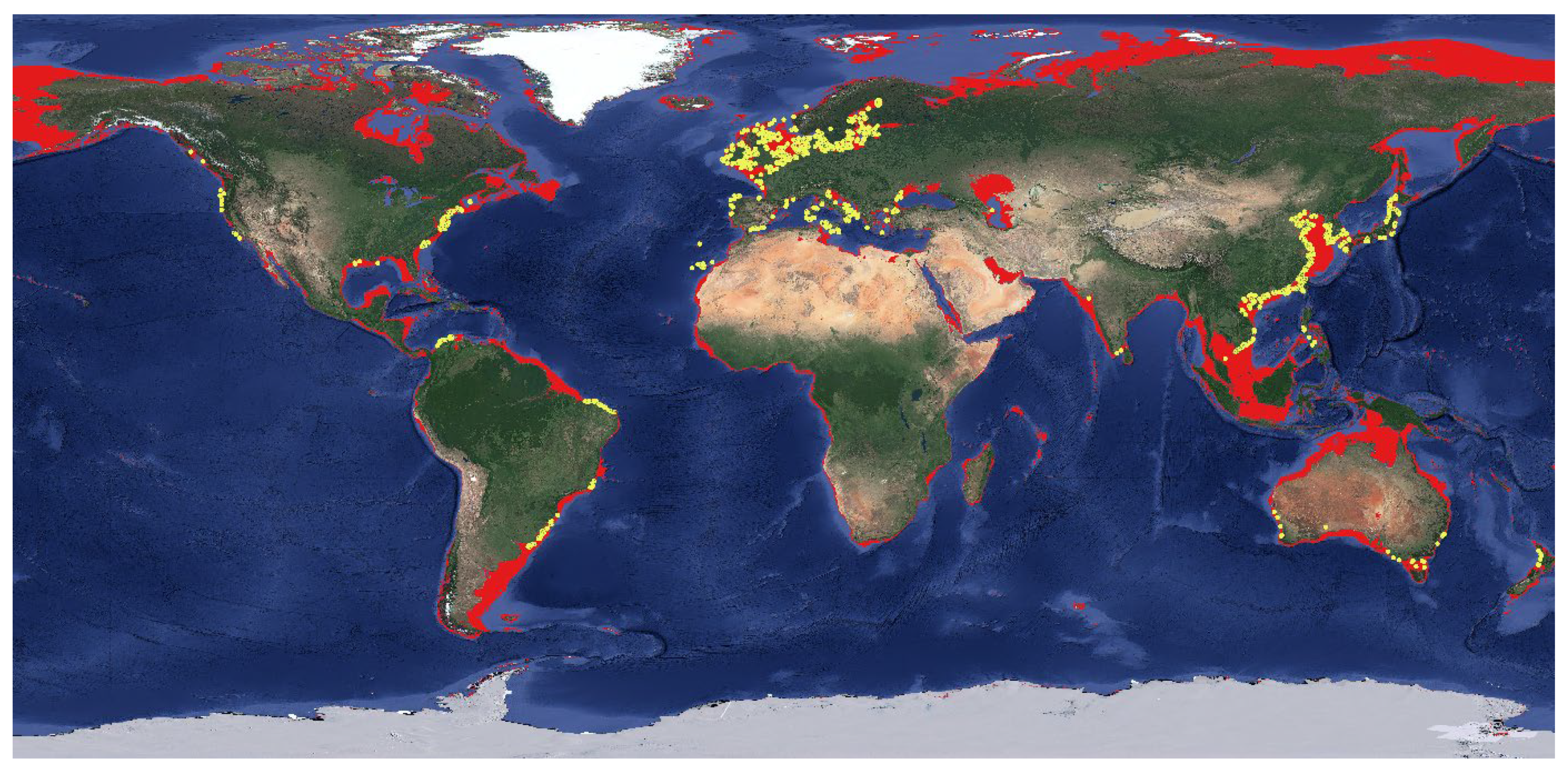

Although much climate debate concerns the challenges of sea level rise, contemporary sea levels around the globe are actually already higher than they have been for most of the last million years (

Figure 1). This means that across the comparatively short time frame in which

Homo sapiens have existed, large areas of previously habitable landscapes around the world are currently underwater (

Figure 2). Many of these landscapes may hold vital pieces of information for answering important archaeological questions regarding how people of the past lived on these lost plains, including how they coped with rising sea-levels and climate change, and how they interacted with other groups inhabiting the currently emergent areas. For deeper prehistory we need to appreciate how these lost landscapes supported our global diaspora as a species, and perhaps even how these landscapes related to our emergence as a contender among other, now extinct, hominins.

Many of the areas discussed here are almost entirely

terra incognita and lie beyond the direct, exploratory reach of archaeologists and contemporary technology [

2]. Given the strategic and informational value of such landscapes, our current inability to undertake direct investigation of surviving archaeological remains, or even to prospect for such sites across many of these areas, is a major challenge to our interpretative schema for the submerged prehistoric record.

Given the significance and context of submerged prehistory and the reconstruction of submerged palaeolandscapes, it should not come as any surprise that research interest in these issues has grown rapidly, along with a concern regarding associated heritage risk at a regional level (Figures 5–8 [

5]). However, any improvements to our archaeological knowledge that have emerged recently have not followed a trend of linear increase, nor do they reflect an even coverage of the areas of continental shelf that are of interest. In those areas where submerged sites are accessible to investigation, there have been important discoveries [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Whilst these include a number of finds relating to earlier periods of time (e.g. [

14,

15,

16,

17]), the majority of discoveries and known sites postdate the Last Glacial Maximum. Most of these finds are linked to waters relatively close to the current shore. Where sites are known, as in the Storebælt waters in Denmark, the majority are later Mesolithic in age, i.e. close to the date of inundation [

12]. Earlier postglacial sites are presumed to exist at greater depths and distances from the current shore [

18,

19,

20]. In these deeper waters, relating to earlier phases of loss, our knowledge of existing archaeology is less substantive. Here, research has largely centred on palaeolandscape reconstruction through the analysis of 2D and 3D seismic surveys, frequently sourced from hydrocarbon and wind energy surveys, and using vibrocore data from a variety of sources.

Although a number of regions have undertaken such studies, the late Pleistocene and early Holocene landscapes of the southern North Sea are among the best understood submerged palaeolandscapes in the world [

21,

22]. Work here is gradually bringing us closer than ever to being able to conduct investigation of the prehistoric landscapes of a continental shelf, although the targeted prospection of archaeological sites within these landscapes remains a challenging proposition [

23,

24]. This situation is repeated elsewhere and in respect of the Gulf of Mexico, Evans and Keith [

25] have suggested that “after four decades of regulatory compliant survey and assessment, no definitive prehistoric archaeological sites have been identified on the outer continental shelf”. Indeed, such comments remain applicable to almost all previously habitable, deep water palaeolandscapes around the world today. This situation remains despite the increasing evidence for the archaeological potential of such areas, as these finds are overwhelmingly the result of chance discovery rather than directed prospection.

It is also true that the opportunities for implementing exploratory methods to remedy this situation may be diminishing across the world’s submerged palaeolandscapes, and, in some places are at a critical juncture. As development of the seabed has increased and diversified, offshore windfarm infrastructure has emerged over the last decade as the largest driving force of change, with coastal nations around the world looking to establish cleaner, renewable, and politically reliable, energy sources. In many areas, much of the continental shelf that is earmarked for development overlaps with submerged palaeolandscapes of strategic archaeological interest, and the rate and extent of ongoing and proposed developments, in the UK [

26] and elsewhere around the world, are accelerating significantly, with 380GW of offshore wind capacity across 32 markets predicted by 2033 [

27] (p. 2). As a consequence, urgent action is needed to establish an appropriate research strategy for the management and investigation of the prehistoric heritage at risk from development, and this should include the combined issues of contemporary and future access as, even after decommissioning, foundations installed into the seabed may not be removed.

Figure 2.

Distribution of offshore wind farm developments, including planned developments as of August 2023 (yellow circles) set against the approximate extent of marine palaeolandscapes (shown in red). Bathymetry source: GEBCO 2021. Wind farm developments information from 4C Offshore [

28].

Figure 2.

Distribution of offshore wind farm developments, including planned developments as of August 2023 (yellow circles) set against the approximate extent of marine palaeolandscapes (shown in red). Bathymetry source: GEBCO 2021. Wind farm developments information from 4C Offshore [

28].

2. Offshore Wind Farm Developments and the Push for Self-Sufficient Greener Energy

Various motives exist for the rush to harness the latent capacity of the marine environment for energy generation. Whilst the quest for energy security may involve an increased reliance on hydrocarbons in the short term, as has been proposed recently in the UK sector [

29], the latest Global Offshore Wind Report recognises that “the twin challenges of secure energy supplies and climate targets will propel wind power into a new phase of extraordinary growth” [

30] (p. 9). In addition, reasons for investment in offshore wind energy infrastructure may include:

These motives, and particularly the primary drivers of climate targets and energy security, have achieved further significance in recent years following several developments, including:

Increased recognition by various governments that global warming, and specifically anthropically induced global warming, presents a grand societal challenge that requires urgent address [

35], particularly among post-industrial nations. The recent leap in global heating suggests that temperatures during 2023 surpassed any other period in the last 100,000 years. Together with the equivocal outcomes of COP 28, the world will probably exceed the 1.5°C goal within the next decade, avoidance of which was previously viewed as a critical target [

36]. Many parts of the developed world now face an existential need to lead on the provision of cleaner sources of energy provision in response to spiralling demands, exemplified, for example, by widespread rises in energy bills across much of Europe since 2021 [

37,

38].

The increased popularity of offshore wind, resulting partly from some of the discontent surrounding terrestrial wind development. The proximity of windfarms to homes and landscapes where space is increasingly contested, and where impacts upon local ecologies are more visible or keenly felt (e.g. [

39]), has encouraged offshore wind investment. Although the continental shelf is itself an increasingly contested and politicised area [

1], it offers many nations with limited terrestrial availability, considerably greater capacity in terms of infrastructure potential. Recent studies in North America have also linked opposition to windfarm development with variable socio-economic and ethnic privileges [

40], revealing that concern over development is a demographically variable phenomenon. Offshore windfarms, by contrast, offer greater opportunity for energy generation [

41], from development areas that are largely out of sight and mind to many onshore communities [

42], although the impact of offshore developments on natural marine resources as well as coastal heritage landscapes (as at St Abb’s Head in Scotland, [

43]), have also generated opposition to development.

Heightened geopolitical tensions around the world have been felt acutely following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022. Some countries that are reliant upon Russian supplies of energy have sought to reduce their dependency in the wake of this event [

44], but even in countries that are relatively less reliant upon Russian sources of energy, such as the UK, there has emerged a greater caution, and a clearer desire to develop self-sufficient sources of energy provision [

45].

Heritage professionals will have to navigate these challenges, and potentially also reckon with the exploitation of archaeological narratives for diverse agendas. These may include disputes relating to rights of determination as justifications for the increased scrutiny of maritime borders [

1,

46]. This is reflected not only by the recent surge in offshore renewable investment, but also the desire to strategically expand jurisdiction over parts of the continental shelf, and presumably maximise the potential utility of this resource. Continental shelves typically extend to 200 nautical miles from land but may be increased through application to UNCLOS (Article 76). The USA has recently announced that it has expanded its Extended Continental Shelf by a million square kilometres, one of 75 nations to undergo such expansion [

47]. The intensifying focus on expansion of territory and assets in this regard further complicates the already politically sensitive nature of continental shelf development. This is now an arena that is multifaceted, complex, increasingly contested and rapidly evolving [46, 1]. The interests of archaeologists and heritage professionals are a small voice among those of multiple larger stakeholders also vying for position [

1], and in such a melee, continental shelf prehistory has proven a difficult aspect of underwater cultural heritage to satisfactorily detect, define, and manage [

48].

3. Characterising Prehistoric Underwater Cultural Heritage

In most parts of the world, save for a few notable exceptions (e.g. [

12]), submerged prehistoric archaeological sites remain a relatively rare phenomenon, restricted to areas relatively close to the current shore, and at relatively shallow depths that are accessible to investigative divers [

49]. Archaeological work further offshore on the continental shelf (i.e., at distance and/or at depth) carries greater logistical difficulties and may incur significant expense [

50]. Nevertheless, these areas hold significant archaeological potential, as evidenced by the accumulation of chance discoveries of artefacts and faunal and human remains, as well as discoveries made from targeted investigation of shallower nearshore waters [

7,

15,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. The southern North Sea is associated with, probably, the best studied and understood submerged palaeolandscape sequence in the world. This has been made possible by an archaeological community which has engaged with palaeolandscape research at the largest scales. In Britain, aside from commercial research, this has involved dedicated research programmes including

Europe’s Lost Frontiers and its predecessor the

North Sea Palaeolandscapes Project [21, 22]. The consequence of this and similar exploratory studies elsewhere within the southern North Sea and its adjacent waters, is that the region can be used as an exemplar for submerged prehistoric archaeological research elsewhere [

57,

58,

759,

60,

61,

62].

The southern North Sea demonstrates that, unlike terrestrial palimpsests, submerged palaeolandscapes have largely escaped the impact of anthropically-induced taphonomy, at least in the sense that they have not been industrialised, intensively farmed, or urbanised [

49]. When submerged prehistoric sites have been found and investigated in or near these waters, some have been field-changing in terms of the insights they offer, as at Tybrind Vig in Denmark, Yangtzee Harbour in the Netherlands, Bouldnor Cliff and Area 240 in the UK, and Hummervikholmen in Norway [

9,

10,

64,

65].

However, across much of the area presumed to be archaeologically significant, the potential for exploration and conservation of heritage resources is complicated by the question of what a site actually is, and how we might recognize such entities in these environments [

49]. This question, apparently theoretical in nature, has significant, practical implications for prospection and legislation, particularly with regards to formal designation. The UK Offshore Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment 4, which considers the environmental impacts of energy development and associated infrastructure, exemplifies this problem. The cultural heritage appendix to this report notes that “designated sites are relatively few in number compared to those which are recorded, and with the exception of shipwrecks, all are terrestrial” [

66] (

p. Xviii).

Consequently, one of the potential pitfalls of heritage management in marine environments is the accepted standard for what might be defined as cultural (rather than natural) remains, a requirement for a practical framework to support workable laws and pragmatic archaeological research strategies. Traces of prehistoric occupation, for example, may often be ephemeral in nature, difficult to detect, only fleetingly accessible, and poorly suited for identification. Recent mapping of uniquely preserved hunter-gatherer landscapes within the Great Lakes, and most recently in the Baltic [

67], demonstrates that significant cultural structures may appear as little more than an alignment of stones or wood [

68]. A hearth may appear in the marine record as a smear of burnt sediment. Natural material with archaeological value, such as peats, sediments and fossilised flora and fauna dating from prehistoric times will only be afforded protection under the UNESCO Convention of 2001 if they are directly associated with evidence of the presence of human communities [

48] (p. 88). Although the dating of such sediments in a marine context may well suggest their archaeological significance, demonstrating clear and unambiguous association with human communities prior to detailed archaeological investigation is complex and fraught with difficulties.

Although, there have been a series of major policy initiatives in the North Sea [

8,

69], as Joe Flatman has remarked “new marine management policies in particular have failed to recognise the complexity of the marine historic resource, continuing to define materials in terms of spot ‘sites’ rather than blended layered cultural locales” [

1] (p. 179). The recognition of landscapes as having an inherent cultural value is generally appreciated in terrestrial contexts, where historic landscape characterisation (HLC) is widely recognised as a significant heritage methodology for the assessment of landscapes at a local, regional, or indeed national level [

70]. An attempt to apply these methodologies offshore has culminated in Historic England’s National Historic Seascape Characterisation dataset (HSC) [

71,

72]. An early attempt to implement HSC in deep waters was undertaken during interpretation of the first large scale archaeological landscape data set from the North Sea [

22], but this remains a unique exercise as, in most situations, the lack or complexity of available data has made these landscapes less conducive to such analysis.

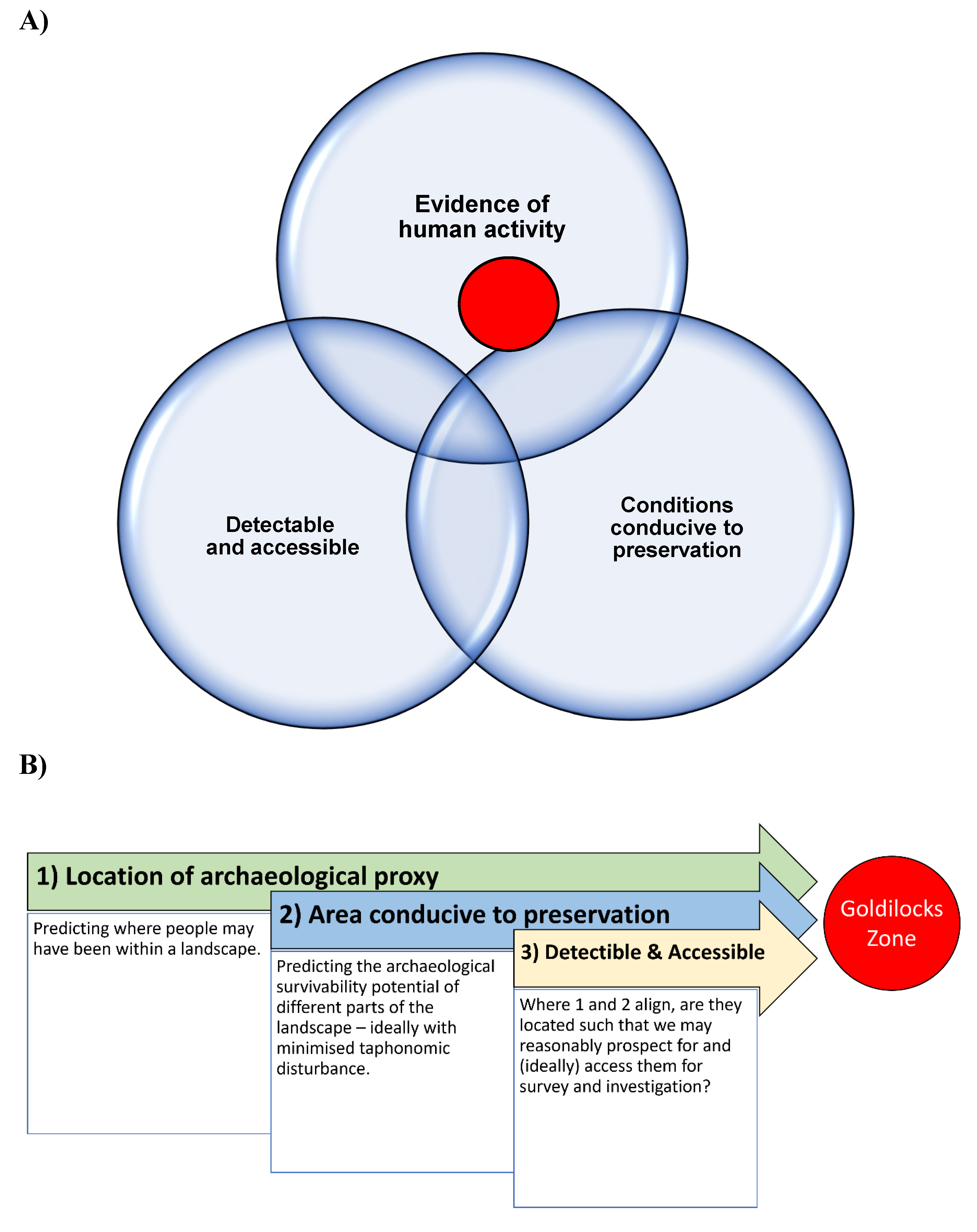

4. The “Goldilocks Zone”

In contrast, an alternative route to landscape assessment, initially proposed as part of the ERC-funded University of Bradford project

Europe’s Lost Frontiers [

21], is to use the concept of a “Goldilocks Zone”, a term initially used in astrobiology to describe a circumstellar habitable zone in which the complex requirements for life may be met. The conditions in such situations are “just right” for the presence of life, in deference to the eponymous fairy tale.

Here, we develop this concept to suggest that deposits with the potential to be of archaeological interest can be identified in a similar manner and provide a route to evaluating and ranking areas of interest and threat in deep waters (e.g. [

22,

73,

74). In the context of a targeted archaeological project, investigating submerged prehistoric remains, we may imagine a hierarchical Venn diagram as illustrated in

Figure 3. Selection of an area of interest requires that the location will:

- (1)

Exist at a position that is both detectable and accessible for recording or investigation.

- (2)

Exist at a location that is (or was) conducive to archaeological preservation, and likely to have withstood significant taphonomic change.

- (3)

Have been a location where human activity took place and at a sufficient intensity to leave archaeological traces.

Any project seeking to undertake archaeological prospection of palaeolandscapes across the continental shelf might seek to identify areas that fit this model. However, as in any model, there are several caveats. First, as noted in respect of the search for extraterrestrial life, the establishment of a Goldilocks Zone may meet the prerequisites for archaeological discovery but does not guarantee the presence of such evidence. Second, it is possible for archaeological discoveries to be made outside of these conditions, and these may result from the presence of archaeological features of a sort not previously known or anticipated by the model. Finally, as the model is devised specifically for locating finds within their primary depositional setting, it does not account for redeposited finds removed from their initial context, although these too may have considerable information value. It is also important to acknowledge that whilst apparently empty regions within marine landscapes may reflect a sparse resolution of relevant marine data, the cultural significance of empty spaces, or areas characterised by apparently low levels of activity, may also be a reflection or facet of a cultural landscape [

75,

76,

77].

Such observations emphasise that heritage managers face a challenge when considering what constitutes an archaeological proxy worthy of investigation, mitigation, or protection. However, in contrast to the chance nature of previous finds in the southern North Sea, the Goldilocks Zone does provide a framework for finding previously elusive, primary archaeological deposits in a targeted manner. However, as on land, redeposited artefacts, “off-site” deposits (see Foley [

79]), and non-material culture proxies of human activity are all still of archaeological interest, and frequently worthy of curatorial management in terms of the information they convey about past lifestyles and land use.

Given the complexity of understanding archaeological landscapes, on land but specifically at sea, the implementation of any methodology may be problematic. In some cases, such outputs may amount to little more than speculative assessments of cultural heritage threat potential, but nevertheless this emphasises that each development proposal must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis [

78] (p. 228).

5. The Legal Context for the Management and Investigation of Continental Shelf Prehistory

Having considered the archaeological context of marine palaeolandscapes and, to some extent, the prerequisites if we are to provide an adequate heritage record for such areas, it is important to understand the legal framework in which marine heritage exists. Laws regarding the protection, curation, and investigation of submerged prehistoric heritage have only recently become an issue for international legislative concern. This may stem in part from an enduring pre-occupation with more tangible archaeological sites and more recent remains, namely discoveries relating to shipwrecks [

80]. However, this also relates to persistent misconceptions regarding the survivability and accessibility of prehistoric archaeology from submerged contexts, and the perceived lack of value in searching for and engaging with such finds [

20], [

81] (p. 35). While recognition of the significance and potential of submerged prehistoric heritage has historically varied from state to state [

82,

83,

84], the shipwreck-dominated focus of marine archaeology began to change only in the late 1980s to include other subjects of interest [

48] (p. 71), [

85] (p. 174). This lag in attention is arguably reflected in the remit and scope of international legislation guidance.

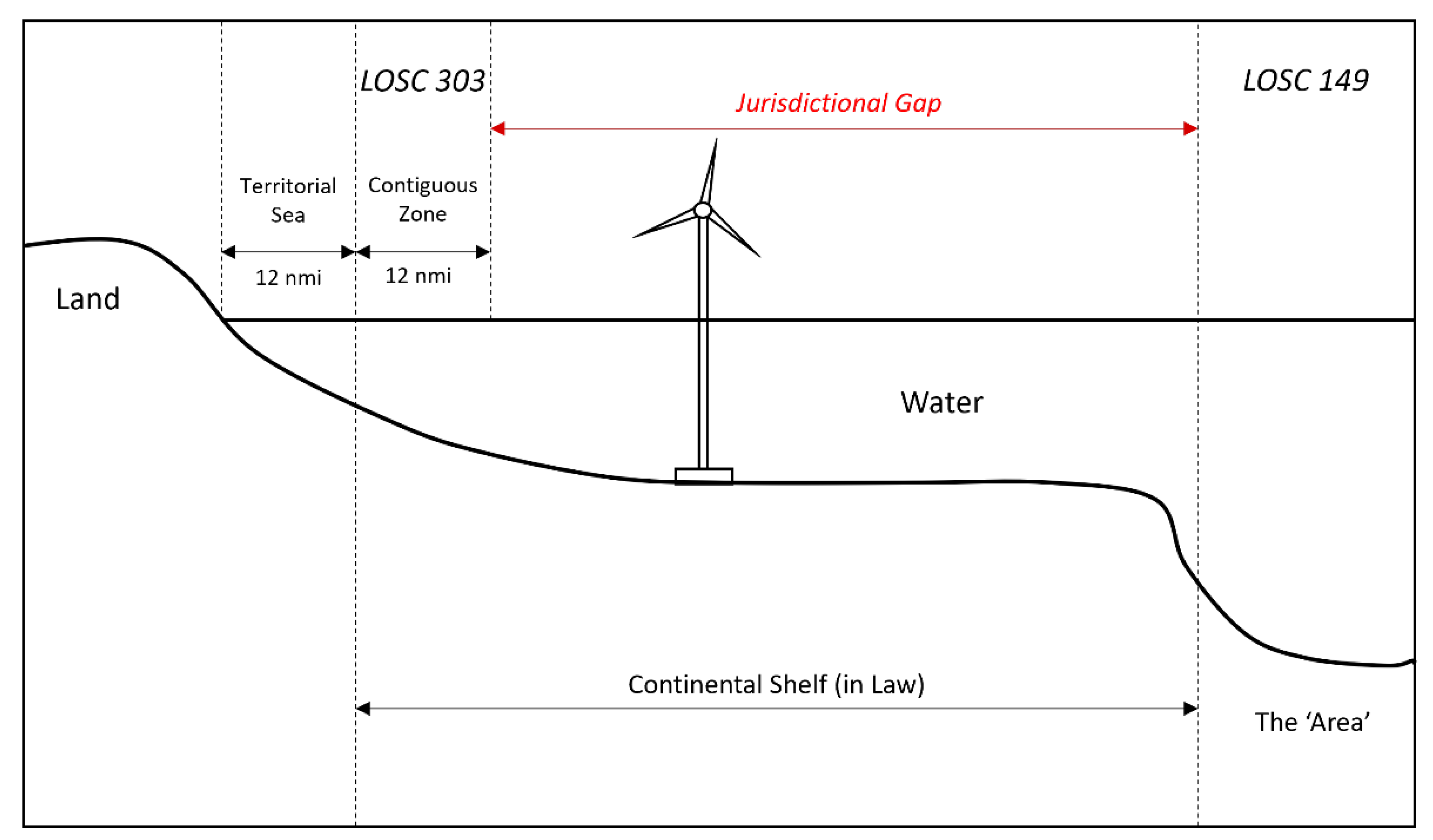

6. The Jurisdictional Gap

To assess the threats facing the archaeology of the continental shelf, several sources of international law must be consulted. These include general principles of international law, the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC or UNCLOS [

86]), and the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (UPUCH [

87]). Various legal experts have discussed the different aspects and shortcomings of these pieces of legislation in both international [

48,

80,

85,

88] and national contexts (e.g. [

90]). One area of concern is what Sarah Dromgoole describes as an effective ‘jurisdictional gap’ [

80]. In essence, the situation is as follows. The 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea divides oceans into three maritime zones, which are afforded different legal regimes under international law. These are ‘Territorial Seas’, ‘the Contiguous Zone’, and the ‘Area’.

Within territorial seas, which are delimited by a 12 nautical mile (22.2 km) perimeter around the shore of a coastal state, a nation has, by virtue of sovereignty over this zone, the right to regulate the removal of underwater cultural heritage. Beyond this zone is formally where the continental shelf begins. It is important to note that this definition of the continental shelf is a legal entity and is not equivalent to the way in which the term is used geologically. The shelf extends as far as 200 nautical miles (NM) from the coastal baseline or, in the case of ‘broad-margin’ states with continental margins that extend far beyond this 200 NM limit, this designation may stretch as far as the deep seabed [

48] (p. 36). The first 12 nautical miles of the continental shelf from the margin of territorial seas, as legally defined, may be declared and then recognised as the ‘Contiguous Zone’. Within this zone, coastal states may extend their right to regulate the removal of underwater cultural heritage under Article 303 of UNCLOS. The ‘Area’ refers to the deep seabed beyond national jurisdiction, or beyond the outer margins of the legally defined continental shelf. Here, underwater cultural heritage falls under protection from Article 149 of UNCLOS. These maritime zone divisions are represented in

Figure 4 and explained in greater detail in Dromgoole [

80].

The key takeaway from this legislative framework is that an area of the continental shelf falls between the protection afforded by UNCLOS Articles 303 and 149, and is the jurisdictional gap as referenced by Sarah Dromgoole [

80]. Whilst there are national variations to the extant laws and conventions impact heritage across Territorial Seas, the Contiguous Zone, and the ‘Area’, a significant portion of the continental shelf around the world has no protective heritage legislation at all. It is in these areas where substantial evidence for submerged prehistoric sites and landscapes may exist, and it is here that existing, but generally unexplored, landscapes remain largely unprotected by the law.

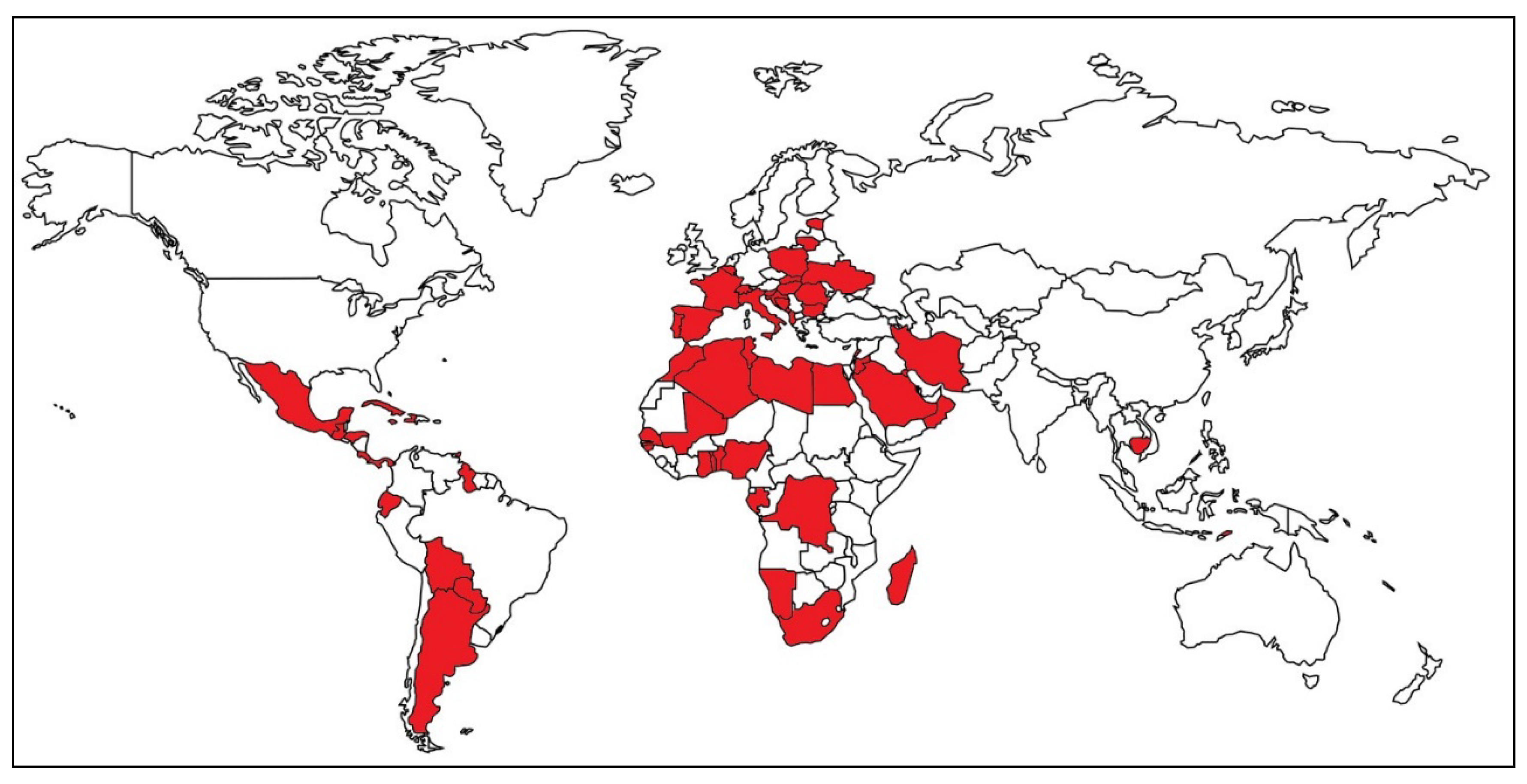

The UNESCO Convention of 2001, which came into force in 2009, sought to address this issue, but as of July 2021 only 69 parties have ratified this treaty (

Figure 5). The provisions and protocols specified by the LOSC and the UNESCO Convention of 2001 have been discussed in detail elsewhere [48, 80], but for coastal states not participating in the latter, the area described by this ‘jurisdictional gap’ remains without legislated regulation. While there are ways around this (see Dromgoole [

80]), currently ‘there is no legal protection afforded to submerged underwater cultural heritage sites expressly by the terms of UNCLOS III’ [

83] (p. 358). As González and colleagues note, among other considerations of a more geopolitically sensitive nature, the unsustainable expenditure presumed by a duty of care to archaeologically significant heritage (and not just prehistoric UCH) within this zone may be a factor dissuading some states from agreement [

87] (p. 61).

7. The UK Portion of the Southern North Sea

Although the UK has not formally ratified the UNESCO convention, it is, in many areas, a leader in the management of marine heritage [

92]. Recent research into submerged palaeolandscapes surrounding the UK (summarised in [

21,

69,

93]), the development history of the UK offshore energy sector [

30], plus the largest offshore wind potential in Europe [

94], makes the UK portion of the southern North Sea an excellent case study for review of UCH in light of the practical and legislative challenges outlined above.

8. Doggerland: A Unique Submerged Landscape

The North Sea, and its UK portion in particular, has benefited from considerable investment into research targeted at the reconstruction of late glacial Pleistocene and early Holocene landscapes [

22,

95,

96,

21]. Other North Sea basin nations may lay claim to richer densities of findspots, but the UK continental shelf has been the subject of a series of research projects incorporating extensive 2D and 3D seismic and vibrocoring surveys aimed at reconstructing palaeolandscape evolution from the late Pleistocene [

22,

21]. The southern North Sea palaeolandscape, often referred to as Doggerland, was a landscape of central importance in northern Europe, larger in area than many current European countries at its peak. It boasts a wealth of unexplored archaeological and environmental data imperative to a range of prehistoric research questions, including understanding how past populations met challenges of climate change and sea-level rise [

97,

98,

99]; see also [

100]. It has been a habitable landscape connecting the British mainland to continental Europe at various points in the past and including critical cultural periods starting with the earliest hominin occupation of Britain [

15,

101].

Our knowledge of the palaeogeography of this landscape stems from innovative research, using energy and extractive industry-generated seismic data, to support the mapping of more than 188,000km

2 of Doggerland’s topography, coastlines, lakes and rivers [

102] (p. 36), [

22,

95,

96]. However, while large portions of Doggerland should be ideal for the preservation and location of prehistoric archaeology [

103], few stratified sites are known from this area, and none from waters more than 12 nautical miles from the current shore. The early Holocene (Mesolithic) site at Yangtze Harbour lies in Dutch Waters [

10], while the much older Middle Palaeolithic site at Area 240 and associated deposits lie within British waters [

13,

14,

64]. However, as the UK Offshore Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment 4 notes, there are few cultural heritage site designations relative to the scale of the resource [

66] (p. 50). Despite this, the quantity and nature of finds and sites from adjacent, shallow coastal waters indicate the potential of the area, and the palaeolandscape research conducted so far provides the best foundation for targeted prospection. Using these data sets, we may begin to think meaningfully about how we locate archaeological deposits, where they are accessible, and if they are at risk from development [

78].

Various other areas of the continental shelf around the globe have been touted for their archaeological potential (e.g. [

104,

105], but so far none have been afforded the extensive palaeolandscape mapping and reconstruction directed at the southern North Sea. The area has the potential to act as an exemplar for other nations looking to develop offshore wind capacity [

106] and provide an international standard for preparatory work and management regarding these aspects of cultural heritage.

9. Offshore Wind and Energy Strategy

In 2020, as part of their goal to become “the world leader in clean wind energy”, the UK government pledged that all homes were to be powered by offshore wind by 2030 [

107]. This was also a significant milestone on route to plans of achieving the national aspiration of net-zero gas emissions by 2050 [

108]. Already a world leader in offshore energy provision (

Figure 7; [

26]), this goal nevertheless requires significant expansion and acceleration of infrastructure installation over the coming years. However, the progression of green policies has recently become the centre of political and public debate within the UK, including objections to the extension of the Ultra-Low Emissions Zone in London [

109] and a proposal to extend licencing for hydrocarbon extraction within UK waters [

110]. Notwithstanding such dialogue, the scale of current plans and envisioned growth is demonstrated by the areas covered by the Dogger Bank A, B and C wind farms which are, currently, collectively set to become the world’s largest offshore wind farm, capable of powering 6 million homes annually [

111].

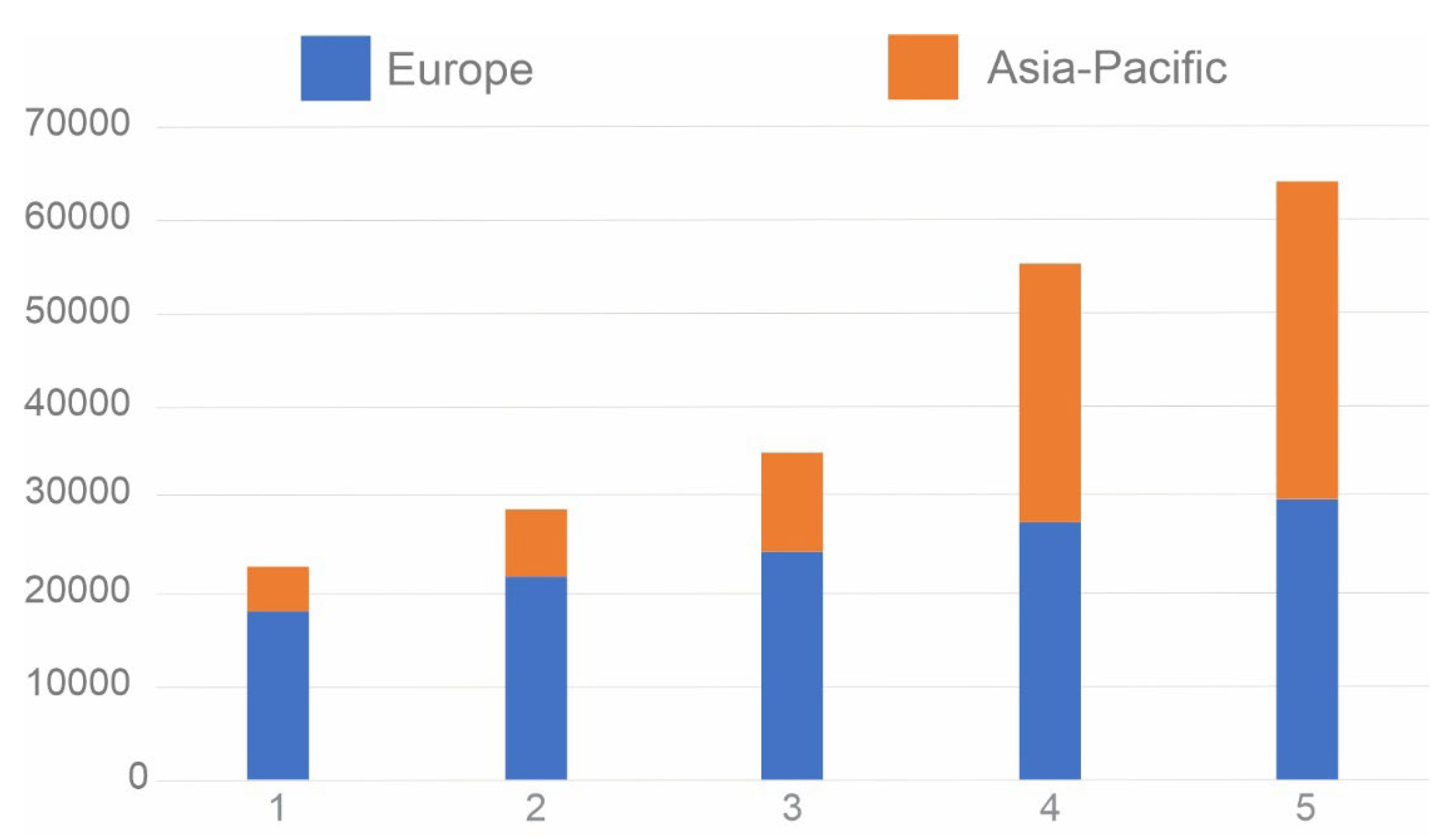

The UK is, of course, not alone in their aspirations to drastically increase offshore wind energy provision. The European market continues to grow and diversify but has recently been outpaced by rapid growth in the Asia-Pacific market, driven primarily by China (

Figure 6; [

112]). Rates of growth are, however, neither stable, nor impervious to fluctuation and 2022 was a notably slower year of growth in terms of Mega Watts installed, dropping from 21106 MW installed in 2021, to 8771 in 2022 [

112] (p. 53), [

30] (p. 10). However, even with the current rates of installation, such expansion will still be not enough to achieve more than two-thirds of the wind energy capacity required by 2030 for a 1.5°C (above pre-industrial levels) and net zero pathway in line with the goals of the IPCC [

113] (p. 16).

Figure 6.

Comparison of Asia-Pacific and European growth rates for offshore installations (by Mega Watts) between 2018 and 2022. An explosion of growth led by China has recently surpassed Europe’s position as the lead market for offshore wind installation. Data from GWEC [

94,

112,

114,

115,

116].

Figure 6.

Comparison of Asia-Pacific and European growth rates for offshore installations (by Mega Watts) between 2018 and 2022. An explosion of growth led by China has recently surpassed Europe’s position as the lead market for offshore wind installation. Data from GWEC [

94,

112,

114,

115,

116].

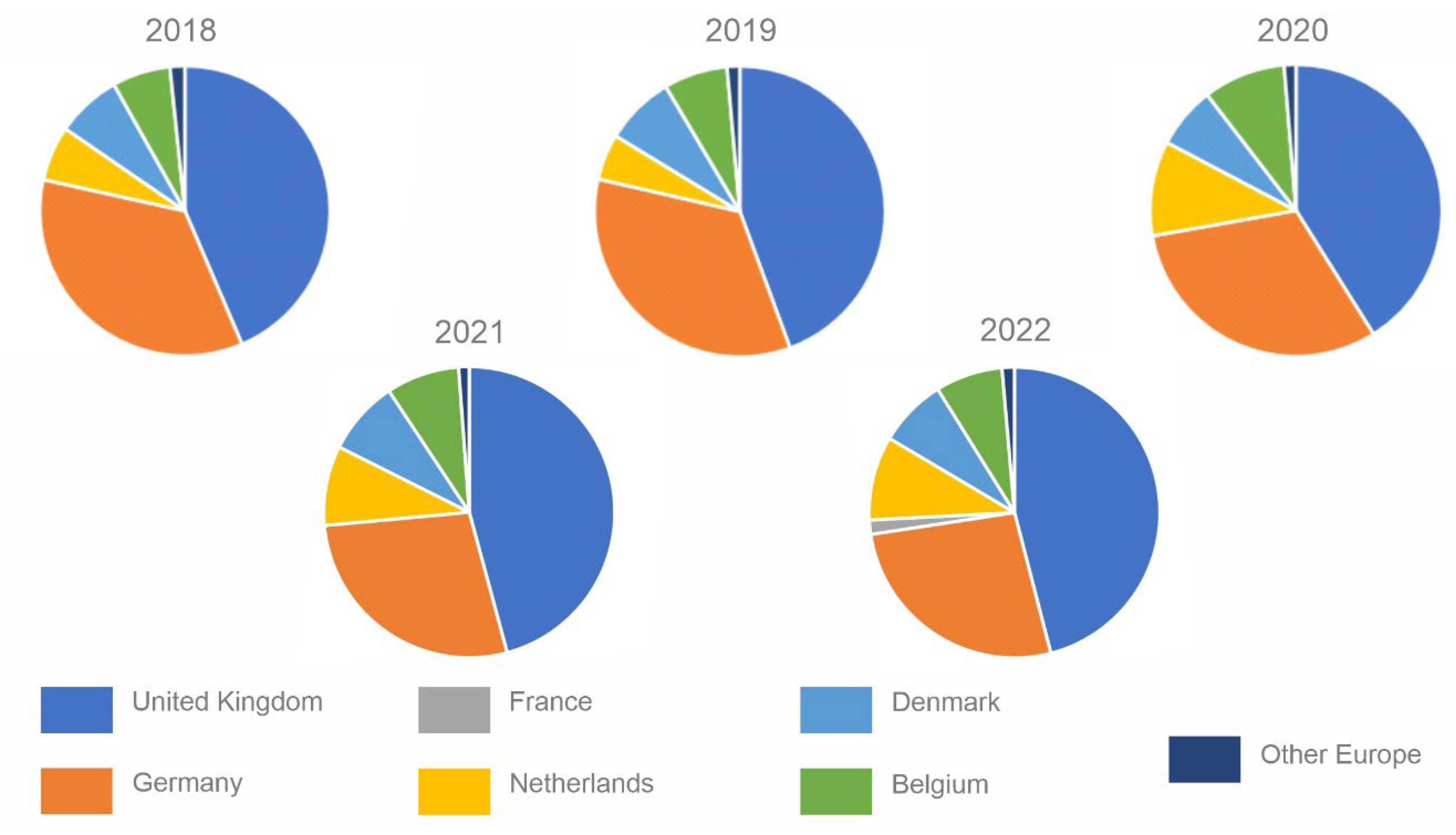

Figure 7.

Showing relative distribution of offshore new wind farm installations in Europe for each year from 2018 to 2022 (in Mega Watts) by country. Data from GWEC [94, 112, 114-116].

Figure 7.

Showing relative distribution of offshore new wind farm installations in Europe for each year from 2018 to 2022 (in Mega Watts) by country. Data from GWEC [94, 112, 114-116].

When assessing the nature and scale of current development, it should be noted that wind farm infrastructure, like hydrocarbon infrastructure, can take a variety of forms (Fig. 4, [

113]), and the type of installation will govern seabed disturbance associated with it. However, the government requires that “physical damage to submerged heritage/archaeological contexts from infrastructure construction, vessel/rig anchoring etc and impacts on the setting of coastal historic environmental assets and loss of access” should be considered at all project phases [

66] (p. xxviii). The text as it stands, however, implies that these comments only cover construction and operation [

66] (p. 17). Yet, wind farm construction, oil and gas extraction, carbon dioxide storage and hydrogen production all require supporting infrastructure (cabling, hubs, pylons, pipelines etc) that may impact surface or shallow subsurface archaeological deposits directly or indirectly. The designation of exclusion zones for these also carry the potential to severely limit access to future heritage researchers. Also, throughout the wind farms' life cycle, scouring of the seabed around the monopiles, influenced by local flow acceleration, is a critical factor affecting the preservation and accessibility of archaeological material within strata. The implications vary with sediment composition; for example, areas underlain by marine clay show limited scour, while those with sandy sediments may experience scour depths up to 1.38 times the monopile diameter [

117]. Monopiles with diameters up to 10 meters are now feasible as the industry advances into deeper waters [

118].

10. Provisions and Guidance

Reviews of recent developments of underwater cultural heritage management in the UK does provide evidence of significant progress in some areas [

82,

119]. Initiatives include the establishment of the Marine Data Exchange portal, the MEDIN data portal, OASIS, the UK repository for development-led archaeological reporting (

https://oasis.ac.uk/) and the archaeological work facilitated by the Marine Aggregate Sustainability Fund (MALSF [

120]). Together, these actions have provided access to data and raised awareness of issues associated with marine prehistory. Engagement with offshore stakeholders has also supported data gathering and academic output (e.g. [

121,

122]), helped to raise awareness of submerged prehistoric UCH and its associated issues [

123] and assisted in potential methodological development and disseminated best practice [

123] (pp. 30-31). More recently, guidance has been developed from the experiences of the first three rounds of offshore wind development [

124], and the revamping of the English North Sea Prehistory Research and Management Framework [

69]. Guidance is, of course, always a work in progress and archaeologists will certainly benefit further from advocating engagement with the expanding offshore sector as part of a broader collaborative endeavour, highlighting the various ways in which archaeological work may support development. Much like the case made for geoscience [

125,

126], the data gathered through survey undertaken for archaeological work may also contribute information of value to developers.

Despite such opportunities, shortcomings with the legislative frameworks have also been identified that render archaeology, and particularly prehistoric archaeology, vulnerable across large portions of the continental shelf [

127]. A recent review of the UK’s legislation for protecting underwater cultural heritage provides a thorough and incisive critique of the status quo, while raising concern over the unfolding impacts of Brexit alongside the UK’s decision not to ratify the UNESCO convention [

128]. In it, they note that there is no “effective legal mechanism for the protection of UCH within the additional contiguous zone permitted for UCH regulation or upon its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf (up to 200 nautical miles)” [

128] (p. 79).

Issues have also been acknowledged with regards to the structure, allocation, reporting and synthesis of archaeological work in the marine domain [

129] (p. 5), [

1] (pp. 177-179). Ultimately, and despite considerable research and mitigation activity across the North Sea, it is not clear to what extent current practice is able to successfully identify archaeological areas of interest in advance of development, particularly if following such protocols becomes a matter of rote [

130,

131]. A primary reason for concern regarding current guidance is best illustrated by the general lack of prehistoric sites located within areas of development within the southern North Sea. Given the dearth of such evidence, strategies such as

in situ preservation, the establishment of widespread exclusion zones, or the scheduling of ‘microsites’ are potentially ill-suited given the nature of much prehistoric archaeology, at least as we currently understand it [

132]. In the UK, consent for development is accompanied by a specified protocol if archaeological remains are unexpectedly encountered [

133,

134], however this is the extent of jurisdiction for much of the continental shelf. Although good practise may be evident in some areas, in respect of reporting frameworks established as part of a consent process and prior to development, for many EEZs archaeological work may be entirely dependent upon the goodwill and cooperation of developer stakeholders who, in any scenario, require input from the archaeological profession as necessary guidance [

123]. This situation will likely remain until our capacity to locate areas of interest improves.

Again, with respect to the UK, the expansion of (then) English Heritage’s remit to cater for the 12 nautical mile periphery in 2002 was a major landmark [

135], and the drafting of the North Sea Prehistoric Research Management Framework (NSPRMF), initially in collaboration with Dutch authorities, was a significant achievement [

93]. An update to the Dutch framework in 2019 [

8], was followed by enhancement to the UK version in 2023 under the auspices of Historic England. This has now become a ‘living’ document, open to evaluative modification [

69].

Currently, UK curators would stress that mitigation measures are primarily designed to support in-situ avoidance of archaeology, and that Environmental Impact Assessments are required in support of development. As the UK has formally declared an Exclusive Economic Zone to 200 nautical miles offshore or the median line with adjacent states, through the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (Section 41), the UK government can set enforceable conditions within this area. In practice, any development consent may contain a written scheme of investigation, a protocol for reporting discoveries; and agreed deposition of reports through the OASIS portal (

https://oasis.ac.uk/). It should be acknowledged that within this framework, the UK Offshore sector has a relatively good track record of compliance with regards to consideration of the historic environment [

135], and examples of the prompt release of data for reuse can also be cited [

136]. However, whilst evidence for compliance to existing heritage guidance is welcome, it remains true that any advice remains, essentially, based on prior archaeological knowledge which, in the case of most marine palaeolandscapes, is largely absent. Given the lack of a substantive archaeological context to guide action, it may not be surprising that many mitigation activities have failed to identify and locate prehistoric archaeology or substantively contribute to refining our knowledge of the seabed in light of their archaeological potential [

11,

13,

137].

The extent to which we wish to remedy this situation and

maximise the value of outputs derived from compliance activity, requires that we must think carefully about the archaeological questions we need to address, how we engage with stakeholders and the practical archaeological challenges that will be faced when attempting such work [

129,

138]. Without this we may not have the capacity to undertake new types of prospective research, and we will run the risk of repeating processes that have not always contributed significantly to our knowledge of palaeoandscapes and their environment.

11. Emerging Opportunities in the North Sea and Globally

Given previous comments, it should not be presumed that archaeologists and offshore developers have no shared interests. Materials fundamental to marine archaeological research, such as buried terrestrial horizons or peat deposits, are also of interest to marine developers during construction and site planning. The establishment of offshore wind infrastructure across much of the southern North Sea will, by necessity, provide information on sediment sequences associated with early Holocene and late Pleistocene deposits [

78], i.e. the best understood stages of landscape evolution [

21,

95,

96].

It has already been stressed that, in addition to the area of the southern North Sea, many other areas of the world’s coastal shelves also contain submerged prehistoric archaeology. Although less well studied, they nevertheless face similar challenges [

6]. Our lack of knowledge in such areas clearly poses a significant challenge [

1,

127], but again presents a major opportunity [

138], to work with industry and identify areas of mutual interest in advance of development. Building on the experience gained in areas including the North Sea, the appropriate integration of evaluative archaeological prospection with the planning or development process would help ensure that sustainable heritage management practices are devised to work in tandem with the development of sustainable energy infrastructure. The benefits of such a development in terms of the efficient use of available resources, enhanced public relations and the demonstration of corporate responsibility might also be significant. As interests dovetail, they present the possibility for a virtuous circle, providing benefits to all involved. It is significant that the UK National Policy Statement for Energy now encourages development proposals that make a positive contribution to the historic environment [

139].

12. Taken at the Flood: Finding Europe’s Lost Frontier

Taken at the Flood is a new collaborative research project, that aims to foster dialogue and cooperative working relationships with other marine heritage professionals, curators, marine industry developers and stakeholders, including offshore windfarms. Based at the University of Bradford Submerged Landscapes Research Centre (

https://submergedlandscapes.teamapp.com/), the project aims to identify the elusive submerged prehistoric archaeology that we believe to be present across the coastal shelves, primarily through the implementation of a methodology based upon the Goldilocks Zone as described above. As part of this, the project will enhance and update previous maps which sought to outline areas of the seabed according to risk, uncertainty, archaeological potential, and accessibility etc [

22,

71]. Our understanding of marine palaeolandscapes has, of course, improved significantly since such analyses were initially attempted [

73,

95,

96,

140,

141], but this remains an important ambition for submerged archaeological prospection [

142], and one that is of importance if we are to utilise a Goldilocks Zone model.

The most recent addition to such extensive mapping was provided through the

Europe’s Lost Frontiers project [

21]. Here a multiproxy approach to landscape evolution reconstruction has provided a relatively detailed overview of the final Pleistocene and early Holocene history of the western portion of the southern North Sea. For parts of this area, the project was able to identify detailed topographic features, trends in landscape evolution over time, and the point at which transgression and eventual inundation occurred. These details, along with an understanding of the relict palaeolandscape relative to the overlying sediment deposits, allow characterisation of survey areas both in terms of a historic landscape used by the final hunter-gatherers of northwest Europe, and a contemporary landscape used as a working environment for archaeologists and marine developers.

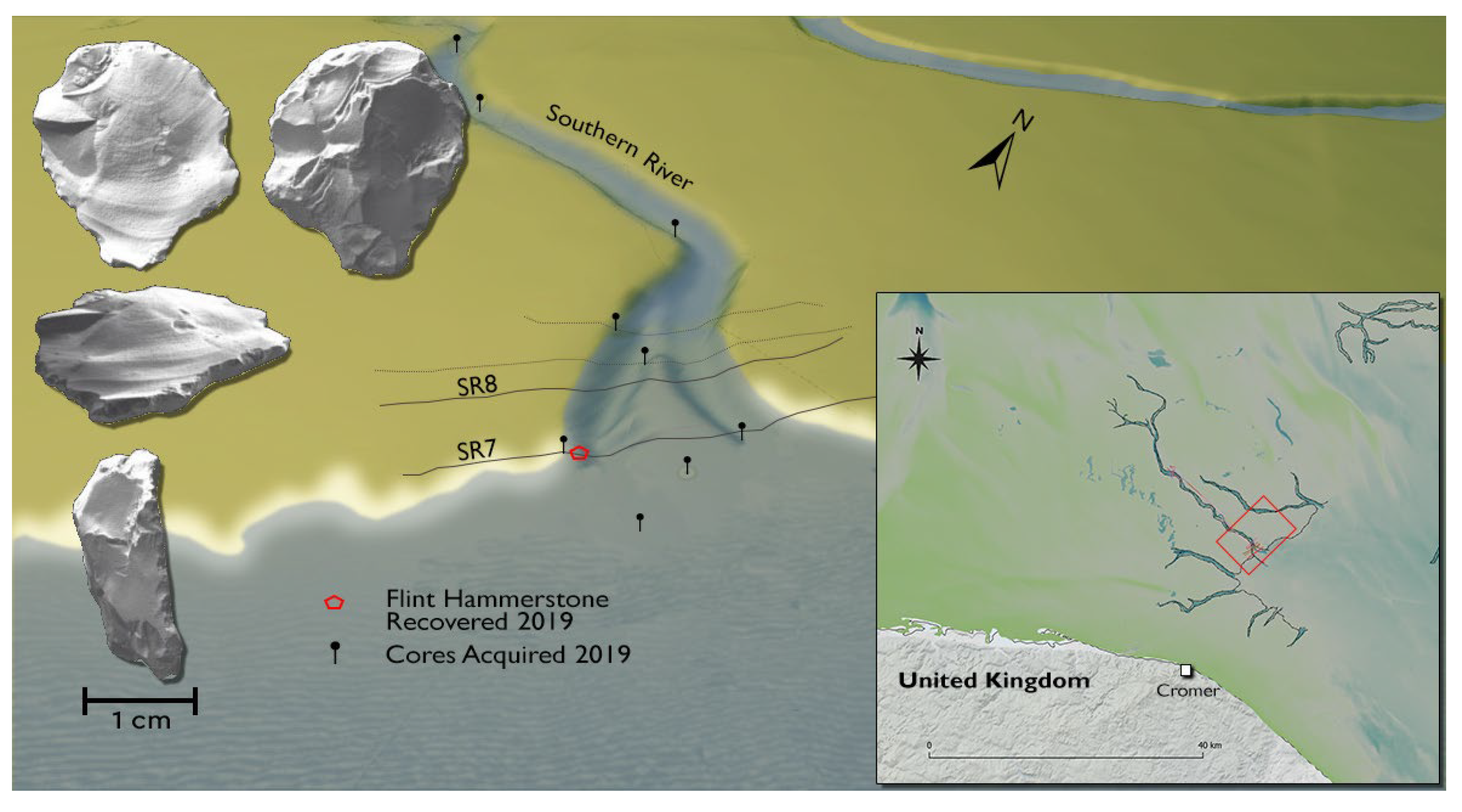

The opportunities provided through such data was evidenced during a 2019 Anglo-Belgian survey expedition, when a worked lithic was recovered from the banks of a submerged palaeochannel, off the Norfolk coast and known as the Southern River valley [

24,

143]. Prior coring campaigns had confirmed the presence of a channel and estuary at this position, but also that contemporary sediments, dated as active in the early Holocene, around 8827±30 cal BP, were exposed at the seabed. Given the archaeologically and ethno-historically attested predilection of various hunter-fisher-gatherer societies for coastal and estuarine ecological settings, and the presence of early Holocene deposits exposed at the seabed in this area, a speculative dredge was undertaken along a transect across the river mouth and the banks [

24]. The recovery of a lithic flake, identified as a possible hammerstone fragment [

23], presumably related to the exposed Holocene surface, was located either on, in, or very close to the dated horizon.

The lithic was recovered close to the iconic ‘Colinda harpoon’ findspot, recovered around 90 years ago from the Leman and Ower banks, [

144]. The significance of the Southern River find, in contrast to the Colinda point and other archaeological artefacts from the North Sea seabed, was that it was not recovered by chance, or through prospection initiated following development work. Instead, it was recovered as the result of archaeological targeted prospection, based upon detailed palaeolandscape survey and prior archaeological expectation [

24]. Currently unique, it is premature to speculate whether the find was recovered

in situ, but the possibility is enticing. Although further testing is necessary to establish the context of the find, the recovery of the Southern River valley flint (

Figure 8) indicates that marine exploration has progressed to the point where directed prospection may at last be feasible and attainable. This contrasts with those discoveries made in the wake of industrial intervention (e.g. [

10,

11), through chance [

9], or alternatively located in shallower waters much closer to the shoreline (e.g. [

12]).

13. Conclusions

Europe currently leads in the study of archaeological, submerged palaeolandscapes [

56], but this position could not have been achieved without the support and collaboration of marine developer stakeholders. It is also true that Europe occupies a significant position in the development of offshore windfarm infrastructure, and that the scale and speed of proposed developments in both Europe and across the globe is likely to continue or gather pace. Such development will, inevitably impact on areas of submerged palaeolandscape of strategic archaeological interest [

28,

145].

Despite this, Martin and Gane state that there is a schism between what UCH heritage policy intends and what it is achieving in practice [

128]. The urgency of their appeal for reform applies to all aspects of underwater cultural heritage, but prehistory is arguably the most vulnerable category. Shortcomings in international and national legislature ensures that large parts of the continental shelf, including areas currently under development, have little or no legal protection for underwater cultural heritage. Signing the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage would at least oblige the implementation of legislation capable of protecting sites and relics in many parts of the globe, and include prehistoric sites and finds, but at present, there is no legal requirement to even report discoveries of prehistoric artefacts [

80]. The inevitable result of the current situation is that in many areas we are entirely reliant upon the goodwill and cooperation of marine developer stakeholders when considering those parts of the marine environment where best-practice guidance, where this exists, has no legal enforcement.

The archaeological community has a duty to consider how future development will impact the marine-historic environment. The need to improve how heritage managers and archaeologists engage with marine developers has been apparent for some time [

134] (p. 52) and yet the challenges facing submerged prehistoric archaeology have now reached a critical position. Future work is urgently required to engage researchers, contract groups, developers and national curators to provide a methodology to remedy this situation. If this is achieved, we may revolutionise our knowledge of submerged prehistoric settlement and land-use, but only if current mitigation practice is substantially updated. Otherwise, our capacity to reconstruct prehistoric settlement patterns, learn from past experiences of climate change, or simply manage what are among the best-preserved postglacial landscapes globally, may be irreparably undermined.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, original draft preparation, writing, review and editing, JW, VG, RH, AF, SF VB. All figures included have been created or re-drafted by the authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by AHRC project Taken at the Flood (AH/W003287/1 00). Data from the Southern River was collected by the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ), partnered by Europe’s Lost Frontiers. This was supported by European Research Council funding through the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (project 670518 LOST FRONTIERS).

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge the support and mentorship of Dr Chris Pater (Historic England) provided during preparation of this paper, and the advice from Dr Claire Mellett (Royal Haskoning DHV), Dr Ruth Plets and Dr Tine Missiaen VLIZ). The roles of other members of the Submerged Landscape Research Centre, including Dr Philip Murgatroyd and Dr Jess Cook-Hale, in improving the paper is also warmly acknowledged. We would like to thank Dr Tom Sparrow for permission to use the digital image of the Southern River lithic used in Figure 8.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Flatman, J. What the Walrus and the Carpenter Did Not Talk About: Maritime Archaeology and the Near Future of Energy, 2012, In: M. Rockman and J. Flatman (eds) Archaeology in Society: Its Relevance in the Modern World: 167-192. New York: Springer.

- Plets, R.; Dix, J.; Bates, R. Marine Geophysics Data Acquisition, Processing and Interpretation Guidance Notes. 2013. English Heritage, Product Code Ref, 51811. [Google Scholar]

- Spratt, R.M.; Lisiecki, L.E. A late Pleistocene sea level stack. 2016, Climate of the Past, Vol. 12, pp. 1079-1092. [CrossRef]

- Dutton, A.; Carlson, A.E.; Long, A.J.; Milne, G.A.; Clark, P.U.; DeConto, R.; Horton, B.P.; Rahmstorf, S.; Raymo, M.E. Sea-level rise due to polar ice-sheet mass loss during past warm periods. 2015, Science, Vol. 349. [CrossRef]

- Sturt, F.; Flemming, N.C.; Carabias, D.; Jöns, H.; Adams, J. The next frontiers in research on submerged prehistoric sites and landscapes on the continental shelf. 2018, Proceedings of the Geologist’s Association 129(5): 654-683.

- Bynoe, R.; Benjamin, J.; Flemming, N.C. Archaeology of the Continental Shelf: Submerged Cultural Landscapes. 2023, In: A.S. Gilbert, P. Goldberg, R.D. Mandel and V. Aldeias (eds). Encyclopedia of Geoarchaeology, Encyclopedia. S: of Earth Sciences Series. Cham: Springer.

- Amkreutz, L.; van der Vaart-Verschoof, S. (Eds.) Doggerland. Lost World under the North Sea. 2022, Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Peeters, J.H.M.; Amkreutz, L.W.S.W.; Cohen, K.M.; Hijma, M.P. North Sea Prehistory Research and Management Framework (NSPRMF) 2019: Retuning the research and management agenda for prehistoric landscapes and archaeology in the Dutch sector of the continental shelf. 2019, Nederlandse Archeologische Rapporten, volume 63.

- Momber, G.; Tomalin, D.; Scaife, R.G.; Satchell, J.; Gillespie, J.; Heathcote, J. Mesolithic occupation at Bouldnor Cliff and the submerged prehistoric landscapes of the Solent (CBA Research Report 164). 2011, York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Moree, J.M.; Sier, M.M. (Eds.) Part 1. Twenty metres deep! The Mesolithic period at the Yangtze Harbour site - Rotterdam Maasvlakte, the Netherlands. early Holocene landscape development and habitation, 2015, in Interdisciplinary Archaeological Research Programme Maasvlakte 2, Rotterdam (BOORrapporten 566): 15-350. Rotterdam: Bureau Oudheidkundig Onderzoek Rotterdam, Gemeente Rotterdam.

- Tizzard, L.; Bicket, A.R.; de Loecker, D. Seabed prehistory: investigating the palaeogeography and Early middle Palaeolithic archaeology in the southern North Sea (Wessex Archaeology report 35). 2015, Salisbury: Wessex Archaeology.

- Bailey, G.N.; Andersen, S.H.; Maarleveld, T.J. Denmark: Mesolithic Coastal Landscapes Submerged. 2020, In G.N. Bailey, N. Galanidou, H. Peeters, H. Jöns and M. Mennenga (eds). The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes, (Coastal Research, Library 35): 39-76. Cham: Springer.

- Roberts, L.; Hamel, A.; Shaw, A.; Mellett, C.; McNeill, E. The Submerged Palaeo-Yare: a review of Pleistocene landscapes and environments in the southern North Sea. 2023, Internet Archaeology 61.

- Shaw, A.; Young, D.; Hawkins, H. The Submerged Palaeo-Yare: New Middle Palaeolithic Archaeological Finds from the Southern North Sea. 2023, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 89: 273-297. [CrossRef]

- Bynoe, R. The submerged archaeology of the North Sea: Enhancing the Lower Palaeolithic record of northwest Europe. 2018, Quaternary Science Reviews 191: 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Bynoe, R.; Dix, J.K.; Sturt, F. Of mammoths and other monsters: historic approaches to the submerged Palaeolithic. 2016, Antiquity 90(352): 857-875. [CrossRef]

- Hublin, J-J.; Weston, D.; Gunz, P.; Richards, M.; Roebroeks, W.; Glimmerveen, J.; Anthonis, L. Out of the North Sea: the Zeeland Ridges Neandertal. 2009, Journal of Human Evolution 57(6): 777-785. [CrossRef]

- Astrup, P.M. The role of coastal exploitation in the Maglemose culture of southern Scandinavia - marginal or dominant?, 2020, in A. Schülke (ed.) Coastal Landscapes of the Mesolithic. Human engagement with the coast from the Atlantic to the Baltic Sea: Abingdon: Routledge. 26-42.

- Astrup, P.M. Sea-Level Change in Mesolithic southern Scandinavia. Long and short-term effects on society and the environment. 2018, Moesgaard: Jutland Archaeological Society.

- Bailey, G. The wider significance of submerged archaeological sites and their relevance to world prehistory, 2004, in N.C. Flemming (ed.) Submarine prehistoric archaeology of the North Sea. Research priorities and collaboration with industry (CBA Research Report 141): 3-10. York: English Heritage/Council for British Archaeology.

- Gaffney, V.; Fitch, S. (Eds.) Europe’s Lost Frontiers. Volume 1: Context and Methodology, 2022, Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Gaffney, V.; Thomson, K.; Fitch, S. (eds). Mapping Doggerland. The Mesolithic Landscapes of the Southern North Sea, 2007, Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Fitch, S.; Gaffney, V.; Walker, J.; Harding, R.; Tingle, M. Greetings from Doggerland? Future challenges for the targeted prospection of the southern North Sea palaeolandscape. 2022, In: V. Gaffney and S. Fitch (eds.) Europe’s Lost Frontiers. Volume 1: Context and Methodology: 208-216. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Missiaen, T.; Fitch, S.; Harding, R.; Muru, M.; Fraser, A.; De Clercq, M.; Garcia Moreno, D.; Versteeg, W.; Busschers, F.S.; van Heteren, S.; Hijma, M.P.; Reichart, G-J. Gaffney, V. Targeting the Mesolithic: Interdisciplinary approaches to archaeological prospection in the Brown Bank area, southern North Sea. 2021, Quaternary International 584: 141-151.

- Evans, A.M.; Keith, M.E. Submerged Prehistoric Archaeology: Confronting Issues of Scale and Context on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf. 2019, Paper presented at the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dawid, L. Current status and perspectives on offshore wind farms development in the United Kingdom. 2019, Journal of Water and Land Development 43 (X-XII): 49-55.

- GOWR (Global Offshore Wind Report). 2023, Global Offshore Wind Report 2023. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- 4C Offshore Windfarm Map Viewer. Available online: https://map.4coffshore.com/offshorewind/. Accessed: Nov 2023.

- Sky News (J. Scott) 01.08.2023. “Rishi Sunak stands by oil drilling expansion as critics warn of climate consequences.”. Available online: https://news.sky.com/story/rishi-sunak-heads-to-scotland-for-net-zero-energy-policy-push-12930459.

- GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council). 2023, Global Wind Report 2023. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- Welch, J.B.; Venkateswaran, A. The dual sustainability of wind energy. 2009, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 13(5): 1121-1126. [CrossRef]

- Kahouli, S.; Martin, J.C. Can Offshore Wind Energy Be a Lever for Job Creation in France? Some Insights from a Local Case Study. 2018, Environmental Modelling & Assessment 23: 203-227.

- Goodman, C. Harnessing the Wind Down Under: Applying the UNCLOS Framework to the Regulation of Offshore Wind by Australia and New Zealand. 2023, Ocean Development and International Law 54(3): 253-276.

- Bocci, M.; Sangiuliano, S.J.; Sarretta, A.; Ansong, J.O.; Buchanan, B.; Kafas, A. Multi-use of the sea: A wide array of opportunities from site-specific cases across Europe. 2019, PLoS ONE 14(4): e0215010. [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A.G.; Stahl, G.K.; Hawn, O. Grand Societal Challenges and Responsible Innovation. 2022, Journal of Management Studies 59(1): 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. 09.01.2024. “Copernicus: 2023 is the hottest year on record, with global temperatures close to the 1.5˚C limit.” Last Accessed: 17.01.2024. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-2023-hottest-year-record.

- Nature Editorial. 14.12.2023. COP28: the science is clear—fossil fuels must go. Nature 624: 225. Last Accessed: 17.01.2024. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-03955-x.

- European Council. Council of the European Union. “Infographic - Energy price rise since 2021.” Last Accessed: 17.01.2024. Available online: www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/energy-prices-2021/.

- Kaldelis, J.K.; Apostolou, D.; Kapsali, M.; Kondili, E. Environmental and social footprint of offshore wind energy. Comparison with onshore counterpart. 2016, Renewable Energy 92: 543-556.

- Stokes, L.C.; Franzblau, E.; Lovering, J.R.; Miljanich, C. Prevalence and predictors of wind energy opposition in North America. 2023, PNAS. 120(40) e2302313120.

- Bilgili, M.; Yasar, A.; Simsek, E. Offshore wind power development in Europe and its comparison with onshore counterpart. 2011, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15(2): 905-915.

- Haggett, C. Over the Sea and Far Away? A Consideration of the Planning, Politics and Public Perception of Offshore Wind Farms. 2008, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 10(3): 289-306.

- National Trust for Scotland (R. Millar). 22.05.2023. “Why we’re objecting to the Berwick Bank windfarm”. Last Accessed 01.11.2023. Available online: https://www.nts.org.uk/stories/why-were-objecting-to-the-berwick-bank-windfarm.

- Kuzemko, C.; Bradshaw, M.; Bridge, G.; Goldthau, A.; Jewell, J.; Overland, I.; Scholten, D.; Van de Graaf, T.; Westphal, K. Covid-19 and the politics of sustainable energy transitions. 2020, Energy Research & Social Science 68: 101685.

- The Guardian (Collingridge, J.; Ambrose, J. ;) 25.09.2021. “Ministers close to deal that could end China’s role in UK nuclear power station”. Last Accessed 01.11.2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/25/ministers-close-to-deal-that-could-end-chinas-role-in-uk-nuclear-power-station.

- Jones, H. ; Commodifying The Oceans. 2022. The North Sea Continental Shelf Cases Revisited. In: I. Braverman (ed.) Laws of the Sea. Interdisciplinary Currents: 49-67. London: Routledge.

- Earth.com (Sexton, C.;). 28.01.2024. “The U.S. just expanded its territory by one million square kilometres”. Available online: https://www.earth.com/news/the-u-s-just-expanded-its-territory-by-a-million-square-kilometers/.

- Dromgoole, S. Underwater cultural heritage and international law. 2013, Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Walker, J.; Gaffney, V.; Fitch, S.; Harding, R.; Fraser, A.; Muru, M.; Tingle, M. ; The archaeological context of Doggerland during the final Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. 2022, In: V. Gaffney and S. Fitch (eds.) Europe’s Lost Frontiers. Volume 1: Context and Methodology: 208-216. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Flemming, N.C. Research Infrastructure for Systematic Study of the Prehistoric Archaeology of the European Submerged Continental Shelf. 2011, In J. Benjamin, C. Bonsall, C. Pickard and A. Fischer (eds.) Submerged Prehistory: 287-297. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Amkreutz, L.; Verpoorte, A.; Waters-Rist, A.; Niekus, M.; van Heekeren, V.; van der Merwe, A.; van der Plicht, H.; Glimmerveen, J.; Stapert, D.; Johansen, L. What lies beneath… Late Glacial human occupation of the submerged North Sea landscape. 2018, Antiquity 92(361):22-37. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.; O’Leary, M.; McDonald, J.; Wiseman, C.; McCarthy, J.; Beckett, E.; Morrison, P.; Stankiewicz, F.; Leach, J.; Hacker, J.; Baggaley, P.; Jerbić, K.; Fowler, M.; Fairweather, J.; Jeffries, P.; Ulm, S.; Bailey, G. Aboriginal artefacts on the continental shelf reveal ancient drowned cultural landscapes in northwest Australia. 2020, PLOS ONE 18(6): e0287490. [CrossRef]

- Galili, E. , Rosen, B.; Evron, M.W.; Hershkovitz, I.; Eshed, V.; Horwitz, L.K.; Israel: Submerged Prehistoric Sites and Settlements on the Mediterranean Coastline—the Current State of the Art. 2020. Skyllis; 13-Heft-2-Quark5.

- Easton, N.A.; Moore, C.; Mason, A.R. ; The archaeology of submerged prehistoric sites on the North Pacific Coast of North America. 2020, The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 16(1): 118-149. [CrossRef]

- Merwin, D.E. Submerged Prehistoric Sites In Southern New England: Past Research and Future Directions. 2003, Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut. 65: 41-66. [CrossRef]

- Flemming, N.C.; Bailey, G.N.; Sakellariou, D. Value of submerged early human sites. 2012, Nature 486(34): 7401.

- Andresen, K. J.; Hepp, D. A.; Keil, H.; Speiss, V. Seismic morphologies of submerged late glacial to Early Holocene landscapes at the eastern Dogger Bank, central North Sea Basin – implications for geo-archaeological potential. 2022. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 525. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.N.; Galanidou, N.; Peeters, H.; Jöns, H.; Mennenga, M. The archaeology of Europe’s drowned landscapes: Introduction and overview; 2020, Springer International Publishing. (pp. 1-23). [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.N.; Harff, J.; Sakellariou, D. (eds); Under the Sea: Archaeology and Palaeolandscapes of the Continental Shelf. 2017, Cham: Springer.

- Fischer, A.; Pedersen, L. (eds); Oceans of Archaeology; 2018, Aarhus: Jutland Archaeological Society.

- Benjamin, J.; Bonsall, C.; Pickard, C.; Fischer, A. (eds); Submerged Prehistory; 2011, Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 287-297.

- Fischer, A. The qualities of the submarine Stone Age. 2018, In (eds) Oceans of Archaeology: 180-191. Aarhus: Jutland Archaeological Society.

- Andersen, S.H. (Ed.) Tybrind Vig. Submerged Mesolithic settlements in Denmark; 2013, Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Tizzard, L.; Bicket, A.R.; Benjamin, J.; De Loecker, D. A middle Palaeolithic site in the southern North Sea: investigating the archaeology and palaeogeography of Area 240. 2014, Journal of Quaternary Science 29: 698-710. [CrossRef]

- Skar, B.; Lidén, K.; Eriksson, G.; Sellevold, B. A submerged Mesolithic grave site reveals remains of the first Norwegian seal hunters. 2016, Marine ventures: Archaeological perspectives on human-sea relations, pp.225-239. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing.

- OESEA4 (UK Offshore Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment 4). OESEA4 Environmental Report. 2022, Department for Business, Energy Industrial Strategy. OESEA4 Environmental Report.

- Geersen, J.; Bradtmöller, M.; Schneider von Deimling, J.; Feldens, P.; Auer, J.; Held, P.; Lohrberg, A.; Supka, R.; Hoffmann, J.J.L.; Eriksen, B.V.; Rabbel, W. A submerged Stone Age hunting architecture from the Western Baltic Sea. 2024, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(8), p.e2312008121. [CrossRef]

- Lemke, A.; O’Shea, J. Drowning the Pompeii premise: frozen moments, single events, and the character of submerged archaeological sites. 2022, World Archaeology 54: 142-156.

- 69. Historic England. North Sea Prehistory Research and Management Framework. 2023, Historic England. Available online: https://researchframeworks.org/nsprmf/introduction/.

- Aldred, O.; Fairclough, G. Historic Landscape Characterisation Taking Stock of the Method. 2002, The National HLC Method Review. English Heritage & Somerset County Council.

- Land Use Consultants; National Historic Seascape Characterisation Consolidation [data-set]. 2018, York Archaeology Data Service, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Natural England; An Approach to Seascape Character Assessment. 2012, Natural England Commissioned Report NECR105.

- Ward, I.; Larcombe, P. Determining the preservation rating of submerged archaeology in the post-glacial southern North Sea: a first-order geomorphological approach. 2008, Environmental Archaeology: The Journal of Human Palaeoecology 13(1): 59-83. [CrossRef]

- Vos, P.C.; Bunnik, F.P.M.; Cohen, K.M.; Cremer, H. A staged geogenetic approach to underwater archaeological prospection in the Port of Rotterdam (Yangtzehaven, Maasvlakte the Netherlands): a geological and palaeoenvironmental case study for local mapping of Mesolithic lowland landscapes. 2015, Quaternary International 367: 4-31.

- Forte, M.; Campana, S. Digital methods and remote sensing in archaeology. 2016, Archaeology in the Age of Sensing.

- Campana, S.R. ; Mapping the Archaeological Continuum: Filling 'Empty' Mediterranean Landscapes. 2018. Springer International.

- Gaffney, V.; Allaby, R.; Bates, R.; Bates, M.; Ch’ng, E.; Fitch, S.; Garwood, P.; Momber, G.; Murgatroyd, P.; Pallen, M.; Ramsey, E.; Smith, D.; Smith, O. ; Doggerland and the Lost Frontiers Project (2015–2020). 2017, In: G. Bailey, J. Harff, and D. Sakellariou (eds). 2017. Under the Sea: Archaeology and Palaeolandscapes of the Continental Shelf: 305-319.

- Ward, I. Depositional Context as the Foundation to Determining the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Archaeological Potential of Offshore Wind Farm Areas in the Southern North Sea. 2014, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 16(3): 212-235.

- Foley, R. Off-Site Archaeology and Human Adaptation in Eastern Africa. An Analysis of Regional Artefact Density in the Amboseli, Southern Kenya. 1981, British Archaeology Reports International Series 97.

- Dromgoole, S. Continental Shelf Archaeology and International Law. 2020, In: G. Bailey, N. Galanidou, H. Peeters, H. Jöns and M. Mennenga (eds) The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes: 495-508. Cham: Springer.

- Easton, N.A. ; Mal de Mer above Terra Incognita, or, ‘What ails the Coastal Migration Theory?’. 1992, Arctic Anthropology 29: 28-41.

- Browne, K. Raff, M.; International Law of Underwater Cultural Heritage. Understanding the Challenges. 2022, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Salter, E.; Murphy, P.; Peeters, H. Researching, Conserving and Managing Submerged Prehistory: National Approaches and International Collaboration. 2014, In A. Evans, J. Flatman and N. Flemming (eds). Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf: 151-172. New York: Springer.

- Frigerio, A. The underwater cultural heritage: a comparative analysis of international perspectives, laws and methods of management. 2013, Unpublished PhD thesis. IMT Institute for Advanced Studies Lucca.

- Martin, C.; Pearson, C.; Harrison, R.F.; Prott, L.V.; O’Keefe, P.J. Protection of the underwater heritage. Protection of the cultural heritage. 1981, Technical handbooks for museums and monuments 4. Paris: UNESCO.

- Suncls, A.; Cai, I.I. United Nations convention on the law of the sea. 1982. United Nations.

- Gonzalez, A.W.; O’Keefe, P.; Williams, M. The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage: a Future for our Past?; 2009, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 11(1): 54-69.

- Dromgoole, S. The legal framework for the management of the underwater cultural heritage beyond traditional territorial limits: recent developments and future prospects. 2007, In: J. Satchell and P. Palma (eds) Managing the Marine Cultural Heritage: Defining, Accessing and Managing the Resource: 33-40. Council for British Archaeology: CBA Research Report 153 89.

- Qureshi, W.A. Underwater Cultural Heritage: Threats and Frameworks for Protection. 2018, George Washington Journal of Energy and Environmental Law 9: 57-69.

- Varmer, O. Closing the Gaps in the Law Protecting Underwater Cultural Heritage on the Outer Continental Shelf. 2014. Stanford Environmental Law Journal 33: 251-287.

- UNESCO. 16.08.2021. Executive Board Two Hundred and Twelfth Session. Implementation of Standard Setting Instruments. “Annex II. Status of ratification of conventions and agreements adopted under the auspices of UNESCO (As at 1 July 2021). Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378425_eng/PDF/378425eng.pdf.multi.page=11.

- Flatman, J.; Doeser, J. The International Management of Marine Aggregated and its Relation to Maritime Archaeology. 2010, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 1(2): 160-184.

- Peeters, J.H.M.; Murphy, P.; Flemming, N. (Eds.) North Sea Prehistory Research and Management Framework (NSPRMF); 2009, Amesfoort 2009. Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed and English Heritage.

- 94. GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council). 2020. Global Wind Report 2020. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- Sturt, F.; Garrow, D.; Bradley, S. New models of North West European Holocene palaeogeography and inundation. 2013, Journal of Archaeological Science 40: 3963-3976.

- Cohen, K.M.; Westley, K.; Erkens, G.; Hijma, M.P.; Weerts, H.J. ; The North Sea. 2017, in N.C. Flemming, et al. (eds) Submerged Landscapes of the European Continental Shelf. pp.147-186. Quaternary Palaeoenvironment: 147186. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Gaffney, V.; Fitch, S.; Smith, D. ; Europe’s Lost World. The Rediscovery of Doggerland (CBA Research Report 160). 2009, York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Leary, J. The remembered land: surviving sea-level rise after the last Ice Age. 2015, Debates in archaeology. London: Bloomsbury.

- Wickham-Jones, C.R. ; Surviving Doggerland. 2021, in: Boric, D.; Antonovicm D.; Mihailovic, B.; Foraging Assemblages Volume 1: 135-141. Belgrade and New York: Serbian Archaeological Society; The Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, Columbia University.

- Conneller, C.; Bates, M.; Bates, R.; Schadla-Hall, T.; Blinkhorn, E.; Cole, J.; Pope, M.; Scott, B.; Shaw, A.; Underhill, D. ; Rethinking Human Responses to Sea-level Rise: The Mesolithic Occupation of the Channel Islands. 2016, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 82: 27-21.

- Sturt, F. ; From sea to land and back again: understanding the shifting character of Europe’s landscapes and seascapes over the last million years, 2015, in A. Anderson-Whymark, D. Garrow and F. Sturt (eds) Continental Connections. Exploring cross-Channel relationships from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age: 7-27. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Fitch, S.; Gaffney, V.; Harding, R.; Walker, J.; Bates, R.; Bates, M.; Fraser, A. A description of palaeolandscape features in the southern North Sea. 2022, In Gaffney, V.; Fitch, S. (eds); Europe’s Lost Frontiers. Volume 1: Context and Methodology: 36-54. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Bailey, G.N.; Flemming, N.C. Archaeology of the continental shelf: Marine resources, submerged landscapes and underwater archaeology. 2008, Quaternary Science Reviews 27: 2153-3165.

- Evans, A.M.; Flatman, J.C.; Flemming, N.C. (eds); Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf. 2014, A Global Review. New York: Springer.

- Bailey, G.N.; Cawthra, H. The significance of sea-level change and ancient submerged landscapes in human dispersal and development: A geoarchaeological perspective. 2021, Oceanologia: 1-21.

- OWIC Offshore Wind Industry Council. 2021. Offshore Wind: Building on the UK’s success (COP26 report) 2021/11.

- British Broadcasting Corporation 06.10.2020. “Boris Johnson: Wind farms could power every home by 2030.”. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-54421489.

- The Crown Estate; “Driving a net zero clean energy future. Offshore Wind Leasing Round 4” 2023. Available online: https://www.thecrownestate.co.uk/our-business/marine/Round4.

- The Conversation (E. Atkins) 26.07.2023. Britain’s next election could be a climate change culture war. Available online: https://theconversation.com/britains-next-election-could-be-a-climate-change-culture-war-210351.

- British Broadcasting Corporation 31.07.23. “Rishi Sunak defends granting new North Sea oil and gas licenses”. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-66354478.

- Dogger Bank Wind Farm. 2024. Website available at https://doggerbank. 20 February.

- 112. GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council). 2022. Global Wind Report 2022. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- Gouvernec, S.; Sturt, F.; Reid, E.; Trigos, F. Global assessment of historical, current and forecast ocean energy infrastructure: Implications for marine space planning, sustainable design and end-of-engineered-life management. 2022, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 154: 111794.

- 114. GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council). 2018. Global Wind Report 2018. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- 115. GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council). 2019. Global Wind Report 2019. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- 116. GWEC (Global Wind Energy Council). 2021. Global Wind Report 2021. Brussels: Global Wind Energy Council.

- Whitehouse, R.J.; Harris, J.M.; Sutherland, J.; Rees, J. ; The nature of scour development and scour protection at offshore windfarm foundations. 2011, Mar Pollut Bull. 2011 Jan;62(1):73-88. Epub 2010 Nov 1. PMID: 21040932. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi W-G.; Gao F-P.; Local Scour around a Monopile Foundation for Offshore Wind Turbines and Scour Effects on Structural Responses. 2020, Geotechnical Engineering - Advances in Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Bicket, A.; Firth, A.; Tizzard, L.; Benjamin, J. Heritage Management and Submerged Prehistory in the United Kingdom. 2014, in: A. Evans, J. Flatman and N. Flemming (eds.) Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf: 213-232. New York: Springer.

- Dellino-Musgrave, V.; Gupta, S.; Russell, M. Marine Aggregates and Archaeology: a Golden Harvest?; 2009, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 11(1): 29-42.

- Bynoe, R.; Grant, M.J.; Dix, J.K. Strategic Support for Marine Development Management: Palaeolithic archaeology and landscape reconstruction offshore. 2022, Historic England Research Report 112, report number 90/2022.

- Brown, A.; Russell, J.; Scaife, R.; Tizzard, L.; Whittaker, J.; Wyles, S.F. Lateglacial/early Holocene palaeoenvironments in the southern North Sea Basin: new data from the Dudgeon offshore windfarm. 2018, Journal of Quaternary Science 33(6): 597-610.

- Satchell, J. Education and Engagement: Developing Understanding and Appreciation of Submerged Prehistoric Landscapes. 2017, in: Bailey, G.N.; Harff, J.; Sakellariou, D. (eds); Under the Sea: Archaeology and Palaeolandscapes of the Continental Shelf: 391-402. Cham: Springer.

- The Crown Estate 2021. Archaeological Written Schemes of Investigation for Offshore Wind Farm Projects. Prepared by Wessex Archaeology on behalf of the Crown Estate.

- Velenturf, A.P.M.; Emery, A.R.; Hodgson, D.M.; Barlow, N.L.M.; Mohtaj Khorasani, A.M.; Van Alstine, J.; Peterson, E.L.; Piazolo, S.; Thorp, M. Geoscience Solutions for Sustainable Offshore Wind Development. 2021, Earth Science, Systems and Society 1.

- Petrie, H.E.; Eide, C.H.; Haflidason, H.; Brendryen, J.; Watton, T. ; An integrated geological characterization of the Mid-Pleistocene to Holocene geology of the Sorlige Nordsjo II offshore wind site, southern North Sea. 2024, BOREAS An international journal of Quaternary research early view.

- Flatman, J. ; Conserving Marine Cultural Heritage: Threats, Risks and Future Priorities. 2009, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites. 2009(1): 5-8. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.B.; Gane, T. ; Weaknesses in the Law Protecting the United Kingdom’s Remarkable Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Need for Modernisation and Reform. 2020, Journal of Maritime Archaeology 15: 69-94.

- Firth, A. Risks, resources and significance: navigating a sustainable course for marine development-led archaeology. 2015, Bulletin of the Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology 39: 1-8.