1. Introduction

Entrepreneurs are widely acknowledged for their pivotal role in shaping societal and economic landscapes, driving change, fostering innovation, and contributing to community development (Carlsson et al., 2013; Migdal, 2018). This study aligns itself with the notion that entrepreneurs and athletes share essential traits that transcend their specific domains (Neck et al., 2023; Ratten, 2018). Characteristics such as enthusiasm, resilience, and flexibility are highlighted as shared elements, constituting a fundamental mentality for achieving success in both entrepreneurship and sports (Scott, 2021). However, it is crucial to recognize that not all individuals, whether high-performance athletes, amateurs, or those disinterested in sports, inherently possess an entrepreneurial mindset (Smith & Westerbeek, 2004). Some individuals naturally gravitate towards an employee mindset, seeking stability and security provided by traditional employment (Mauer et al., 2017). The initial process of discerning one’s category is exceptionally crucial, serving as a protective measure against potential financial losses, wasted energy, and time. One fundamental goal of this research is to facilitate young individuals in consciously determining whether they possess the mindset suitable for venturing into the business world (Baluku et al., 2018). This need arises from the high number of startup failures within the first three years, emphasizing the significance of self-awareness before embarking on entrepreneurial endeavors (Hägg & Jones, 2021).

The variation in entrepreneurial inclination is accentuated by the wide array of attitudes observed among individuals, particularly within the sports domain (Arikatla & Gregorich, 2021). Certain athletes demonstrate entrepreneurial qualities, including a visionary outlook guiding decisions and actions toward long-term goals. They actively engage in networking to build valuable connections fostering collaboration and growth. Conversely, a subgroup of athletes opts for a conservative mindset, prioritizing stability and structure in their endeavors, in contrast to their more entrepreneurial counterparts (Lounsbury et al., 2009). The dichotomy between entrepreneurial and employee mindsets within the sports domain reflects the broader spectrum observed in society.

Examples from the literature illustrate this variability in entrepreneurial attitudes. For instance, studies have shown that some high-performance athletes, despite their competitive nature, may not necessarily possess a natural inclination towards entrepreneurial endeavors (Zhao et al., 2010). In contrast, individuals with a passion for sports may exhibit entrepreneurial attitudes, channeling their enthusiasm into creating sports-related businesses (Ratten, 2015).

The intersection of sports and entrepreneurship is multifaceted, requiring a nuanced understanding of how diverse attitudes coexist within the sports domain. As entrepreneurs and athletes share certain characteristics, the intricate relationship between their mindsets contributes to the richness of the entrepreneurial landscape in sports. Acknowledging and exploring these variations is imperative for comprehensively understanding the potential transition of sports domain students to entrepreneurship (Steinbrink et al., 2020). Beyond possessing traits such as innovativeness, resourcefulness, effective time management, strong leadership skills, and unwavering tenacity, entrepreneurial attitudes emerge as pivotal elements that significantly shape individuals’ inclination towards engaging in entrepreneurial endeavors (Awais, 2023; Drennan, 2020). By delving into these attitudes, the study aims to provide a nuanced perspective on the complex interplay between sports, entrepreneurship, and individual inclinations.

Through rigorous research, the article accomplished the following research objectives:

1. Development of an opinion questionnaire aimed at capturing the nuances of entrepreneurial attitudes and tendencies among students in the field of sports.

2. Analysis of internal consistency - this involves calculating and interpreting the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to assess the internal consistency of questionnaire elements measuring entrepreneurial attitudes.

3. Examination of gender differences in entrepreneurial attitudes - this objective entails investigating and analyzing significant variations in entrepreneurial attitudes between male and female students with a background in sports, utilizing the Chi-Square test of Homogeneity.

4. Assessment of the impact of sports engagement -this involves evaluating the influence of different types of sports engagement (intensive individual sports, intensive team sports, amateur sports, and non-athletes) on students’ entrepreneurial perspectives, using the Chi-Square test of of Homogeneity.

5. Conducting comparative analysis - this objective focuses on making comparisons using descriptive statistics and chi-square tests to identify significant differences in entrepreneurial behaviors based on gender and sports engagement.

6. Identification of key factors - this includes exploring and identifying key factors influencing entrepreneurial attitudes, such as risk-taking propensity, preferences for employment stability, interest in developing personal businesses, willingness to step out of the comfort zone, and adaptability to change.

7. Providing implications for future research -this objective involves discussing study limitations and proposing directions for future research to understand the interaction between sports engagement, gender, and entrepreneurial attitudes.

This research aims to enhance our understanding of divergent entrepreneurial attitudes among athletes and non-athletes, as well as between male and female students. It seeks to establish a robust foundation for effectively engaging and supporting individuals in their transition to entrepreneurship or other career paths post-sports.

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Entrepreneurial Attitudes in the Intersection of Business and Sports

Entrepreneurial attitudes serve as foundational elements that significantly influence individuals’ perspectives and inclinations toward engaging in entrepreneurial endeavors (Jones & Jones, 2014). These attitudes encompass a range of characteristics, including passion, determination, and adaptability, which are identified as commonalities crucial for success in both entrepreneurial and sports contexts (Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014). It is essential to delve into these attitudes to gain a comprehensive understanding of the intricate interplay between sports, entrepreneurship, and individual proclivities.

Ratten (2018) argues that entrepreneurs and athletes, irrespective of their performance levels, share essential traits that extend beyond their specific fields. The capacity to embody initiative, leadership, and self-confidence serves as a unifying force, fostering a shared mindset of success and excellence across diverse domains (Neck et al., 2023). Despite the apparent distinctions in their chosen fields, both entrepreneurs and athletes are characterized by a dedicated commitment to proactiveness and a willingness to take risks in the pursuit of their respective goals (Pellegrini et al., 2020).

Sarkar and Fletcher (2014) assert that individuals in both entrepreneurial and sports domains face significant challenges, undertake risks strategically, and leverage their unique skills to achieve their objectives.

The shared attributes of determination, discipline, and resilience stand out as notable commonalities between entrepreneurship and sports, underscoring the parallels in qualities essential for success in both realms (Brady & Grenville-Cleave, 2017; Bennis et al., 2015). Profound comprehension of effort management and the ability to optimize performance in competitive environments are prerequisites for success in both fields. Entrepreneurs, akin to athletes, develop strategies to navigate complex markets and competitive landscapes, showcasing the strategic thinking required in both domains (Ratten, 2011).

Moreover, the capacity to adapt and learn from failures emerges as a critical aspect in both entrepreneurial and sports endeavors (Stambaugh & Mitchell, 2018). Both entrepreneurs and individuals in the field of sports recognize that failures are inherent in the process and provide invaluable opportunities for continuous learning and improvement. This shared mindset of transforming failures into growth experiences is a common trait between the two, emphasizing the resilience and adaptability required for success (Tarkenton, 2015; Krumins, 2022).

In essence, entrepreneurial attitudes encompass a spectrum of qualities that go beyond individual attributes or traits. They represent a holistic approach, incorporating passion, determination, adaptability, and strategic thinking, which are vital for success in entrepreneurial and sports contexts alike. Understanding and acknowledging the diversity of these attitudes is crucial, as highlighted by the trend among specialists, paving the way for tailored entrepreneurial development programs that cater to the varied needs and aspirations of individuals, especially those in the sports domain.

Based on these foundational premises, this research endeavors to provide a more comprehensive elucidation of entrepreneurial attitudes among students in academic sports programs, taking into account their diverse levels of engagement in sports activities. Consequently, the study formulates the following hypotheses to systematically explore the multifaceted landscape of entrepreneurial attitudes within the context of sports academic programs:

H1: A discernible contrast exists in terms of assumption of responsibilities, and proactive initiative between students not involved in sports and those who are athletes enrolled in sports academic programs.

H2: Variations emerge in the determination to establish their own businesses among individuals with different levels of sports involvement, including amateurs, non-sport individuals, and athletes enrolled in sports academic programs.

H3: There exists a noticeable disparity in the proactive approach to problem-solving, the willingness to exert effort to achieve goals, the tendency to complete tasks, and the readiness to embrace challenges between athletes and non-sport individuals enrolled in sports academic programs.

H4: There is a discernible difference in the prioritization of work-life balance and openness to personal development between athletes and non-sport individuals enrolled in sports academic programs.

1.1.2. Navigating the Challenges of Transitioning to Entrepreneurship

Contrary to the routine lifestyle of individuals deeply immersed in sports, characterized by rigorous training, frequent competitions, and regular travel, this distinctive existence operates within a "bubble" defined by intensive physical and mental preparation for peak performance in competitions (Stefanica, 2020; Menke, 2016). Sports clubs manage logistical aspects such as accommodation, meals, and transportation for athletes, encapsulating them in this specialized environment (Constantin et al., 2020; Rusu, 2018; Kenny, 2015). However, the conclusion of a sports career marks a significant shift, bringing forth a new reality marked by limited financial resources and a sudden transition to an environment where their athletic skills may not seamlessly translate into the job market (Boyd et al., 2021; Rusu et al., 2022; Ramos et al., 2022).

This transition places athletes in a delicate situation, requiring adaptation to life beyond the confines of the sports bubble. The skills demanded in the job market may differ or prove insufficient, posing challenges to their reintegration into society outside the sports sphere. The strict training regimen and exclusive focus on performance during their sports careers can potentially impede the development of certain social or professional skills (Atilgan & Tukel, 2021). Additionally, limited resources and a lack of formal education can pose obstacles to finding a new career direction, emphasizing the need for a well-thought-out post-sports career trajectory (van Rensburg & Kanayo, 2022). As an encouragement for athletes aspiring to become entrepreneurs, Kurczewska and Mackiewicz (2020) assert that individuals with more diversified educational and professional backgrounds have higher chances of initiating a business and an elevated likelihood of entrepreneurial success. Notably, managerial experience surprisingly demonstrated a negative influence on the probability of initiating a business, whereas its impact on the odds of entrepreneurial success was deemed statistically insignificant. This insight provides valuable considerations for athletes contemplating entrepreneurial ventures, emphasizing the importance of diverse backgrounds and suggesting a nuanced relationship between managerial experience and entrepreneurial outcomes.

Psychological aspects, such as the loss of identity tied to sports performance and the adjustment to a new lifestyle, remain prominent in this delicate transition (Gliga et al., 2018; Warriner & Lavallee, 2008). Difficulties in integrating into real life after the conclusion of sports careers become evident, emphasizing the need for strategic planning and support systems (Voorheis et al., 2023).

Linnér et al., (2020) address a fundamental question arising in a society where sports play a dual role, serving not only as a form of physical expression but also as a way of life. This inquiry delves into the challenges associated with reintegrating athletes into society post the culmination of their sports careers. Consequently, our study seeks to comprehensively understand the perspectives of students in the sports domain regarding the potential transition to entrepreneurship. It aims to shed light on both the advantages and potential challenges linked to this shift in their post-sports career trajectory.

In light of the aforementioned considerations, the study introduces the following hypotheses to systematically investigate specific aspects of athletes’ experiences:

H5: A noticeable contrast exists in the perception of the comfort zone between athletes and a category comprising amateur and non-sport individuals enrolled in sports academic programs.

H6: A discernible difference emerges in the perception of post-sports career adaptation between athletes and non-sport individuals enrolled in sports academic programs.

H7: There is a discernible discrepancy in the expectation of receiving clear direction, belief in workload proportional to gains, and avoidance of workplace problems between athletes and non-sport individuals enrolled in sports academic programs.

1.1.3. Gender Disparities in Entrepreneurial Perspectives

Gender disparities in entrepreneurial intention have been a subject of scholarly investigation, revealing intriguing insights into the attitudes and perceptions of male and female students. The study by da Costa et al. (2023) highlights the gender-based variations, demonstrating that male students tend to show a heightened interest in entrepreneurship, coupled with greater confidence in their entrepreneurial capabilities, compared to their female counterparts. This observation reflects prevalent societal norms and biases associating entrepreneurship more strongly with male career paths. Consequently, this section explores the implications of such gender biases and advocates for a reevaluation of entrepreneurship education within the sports domain, aiming to challenge stereotypes and foster increased entrepreneurial engagement, especially among women.

In contrast, the findings of Puyana et al. (2019) introduce a positive correlation between desire, viability, and entrepreneurial intention across both genders. The study recommends targeted university policies to enhance women’s perceived desire for entrepreneurship, emphasizing the importance of interventions such as sessions or training courses featuring women leaders in business.

Adding to the discourse, the research conducted by Westhead and Solesvik (2016) uncovers distinctive patterns, noting that women students are less likely to express high entrepreneurial intention intensity. However, an interesting nuance emerges among women with entrepreneurial education who highlight the alertness skill, showing a higher likelihood of reporting intense entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, the influence of risk perception skill on intention differs between genders, presenting valuable insights for shaping targeted interventions and educational strategies. This section aims to delve into these gender-specific nuances, providing a comprehensive exploration of the multifaceted relationship between gender and entrepreneurial attitudes in the context of business risk, workplace comfort and security, and sports-oriented approaches in business.

H8: There is a discernible difference in how male and female students, enrolled in sports academic programs, perceive business risk as well as comfort and security in a stable workplace.

H9: There is a significant contrast in how the applicability of sports-oriented approaches in business is perceived among male and female students engaged in sports academic programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

To comprehensively explore entrepreneurial attitudes, transition perspectives, and challenges, we collected data through online questionnaires from a sample of 415 Romanian university students (54.9% men; 45.1% women, mean age of men: 23.97; mean age of women: 22.51) across four universities in four different counties of Romania. Convenience sampling was employed, selecting participants based on their availability and accessibility, and they anonymously completed the questionnaire.

The distribution of participants by gender and type of sports activity is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Activity Types of Survey Participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Activity Types of Survey Participants.

| Gender |

Activity Type |

Frequencies |

% |

Total |

M

54.9% |

High-Performance Individual Sport |

52 |

22.8 |

228

100% |

| High-Performance Team Sport |

81 |

35.5 |

| Amateurs (1 year of practice, non-competitive) |

61 |

26.7 |

| Non-practitioners of sports |

34 |

14.9 |

F

45.1% |

High-Performance Individual Sport |

39 |

20.8 |

187

100% |

| High-Performance Team Sport |

26 |

13.9 |

| Amateurs (1 year of practice, non-competitive) |

46 |

24.5 |

| Non-practitioners of sports |

76 |

40.6 |

| |

|

Total |

415 |

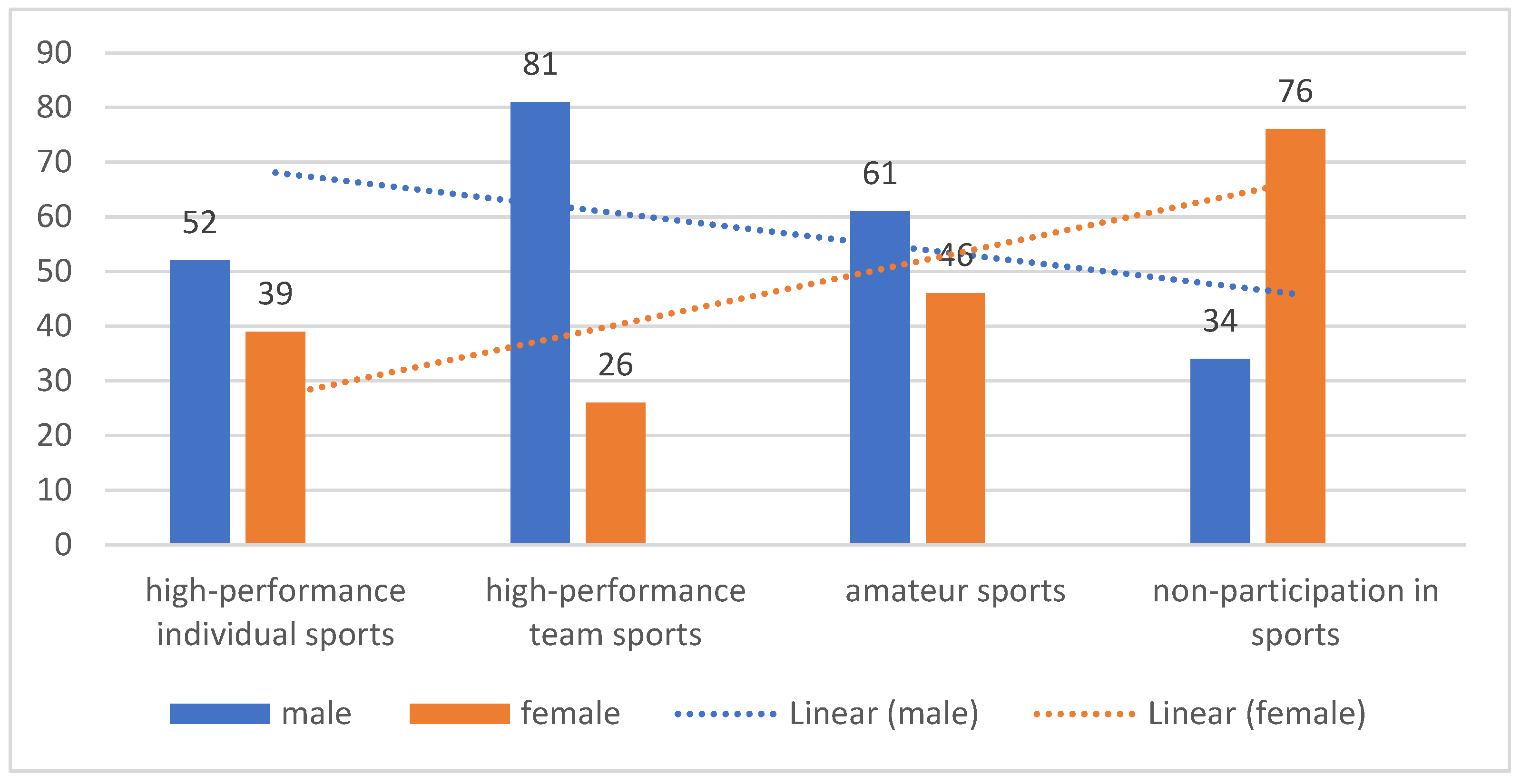

The outcomes of the statistical analysis draw attention to substantial gender discrepancies. There is a statistically significant difference between the respondents’ gender (male-female) and the type of sports participation (engagement in high-performance team/individual sports, amateur sports, non-participation in sports). The minimum frequency from which we can appreciate the sports activity of the respondents (according to the output of the Chi-square test) is 41.00. The result [χ2 (3) = 44.653; sig 2 sides = 0.001; p<0.05] indicates that students from academic sports programs generally participated in sports in various forms, unlike their counterparts from the same programs, the majority of whom either did not engage in sports or participated in a non-competitive manner (amateur sports).

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of significant differences in sports participation based on respondents’ gender within academic sports programs. To assess this relationship, we conducted a Chi-square test, and the results indicate the presence of a significant difference between respondents’ gender and the type of sports participation.

2.2. Dataset and Analysis Techniques

The research intervention unfolded across four stages, aligning with the first semester of the academic year 2023-2024, spanning 14 weeks. This timeline alignment ensured a well-organized and comprehensive exploration of the interplay between sports backgrounds and entrepreneurial perspectives among the study participants.

Stage I – Literature Review (October 2023):

During this stage, an extensive bibliographic study of specialized literature was conducted. Utilizing platforms such as Google Scholar, a thorough theoretical approach was undertaken to assimilate existing knowledge, frameworks, and relevant theories regarding the intersection of sports backgrounds and entrepreneurial attitudes and perspectives.

Stage II – Questionnaire Development (November 2023):

In the second stage, three focus groups were organized to engage with the practical realities. The questionnaire development was based on insights gathered from these focus groups, which included specialized coaches (focus group 1), sports-oriented non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (focus group 2), and representatives from student associations (focus group 3).

Stage III – Sociological Case Study (December 2023):

The core of the research involved the execution of a sociological case study. Using Google Forms to administer a detailed questionnaire, the survey method was employed to collect primary data, providing insights into the entrepreneurial attitudes and perspectives of students with diverse sports backgrounds. This stage aimed to capture nuanced information about the participants’ experiences and insights.

Stage IV – Statistical Analysis (January 2024)

The data obtained from the responses to the questionnaire underwent analysis using SPSS Statistics 20 Core System (Rode & Ringel, 2019). To assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire items, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (α) was utilized, examining the proportion of common variance among all items reflected in the total score (Koning & Franses, 2006). Fidelity, a crucial aspect in psychological assessment and scientific research, was emphasized (Wilkinson & Task, 1999). The present research aimed to maximize response options using a Likert scale with 5 response items, ranging from the smallest extent (1) to the very great extent (5).

2.3. Mesures

The consistency of the items ranges between 0.732 (Item 9) and 0.753 (Item 14). The average Cronbach’s alpha result is 0.755, indicating, based on the interpretation scale (Ercan et al., 2007), good consistency of the questionnaire items (result between 0.7 and 0.9).

The correlations between the questionnaire items are relatively low, with the highest value observed between item 4 and item 6 being 0.443, suggesting that the questions addressed different issues, and the responses exhibit limited similarity.

These findings collectively establish a robust foundation for comprehensively understanding the study variables. The level of consistency revealed by Cronbach’s Alpha aligns with, and even surpasses, the benchmarks set by previous authors (Koning & Franses, 2006), emphasizing the questionnaire’s reliability and efficacy.

The Chi-Square test for homogeneity (Johnson et al., 2015), were conducted on the 15 items across four criteria: gender, competitive sports background versus the rest of the group, high-performance individual sports background versus high-performance team sports background, and amateur sports versus non-practitioners of sports. Out of the 60 performed comparisons, nine revealed statistically significant differences (p<0.05), offering valuable insights relevant to the entrepreneurial perspective based on participants’ sports backgrounds. The outcomes were scientifically interpreted to derive meaningful conclusions, effectively addressing the research objectives.

3. Results

Within the analysis, several items show no statistically significant differences across diverse categories. We have grouped and summarized these items for enhanced clarity in Table 2.

The checkmarks indicate that the differences in responses across gender, athletic engagement, competition type, and non-competitive engagement were not statistically significant (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Overview of Items with Non-Significant Differences.

Table 2.

Overview of Items with Non-Significant Differences.

| Item |

Aspect Considered |

Gender (p>0.05) |

Athletic Engagement (p>0.05) |

Competition Type (p>0.05) |

Non-Competitive Engagement (p>0.05) |

| Item 4 |

I seek solutions and proactively solve problems |

✓¹ |

✓² |

✓³ |

✓* |

| Item 5 |

I expect clear instructions and direction from superiors |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Item 6 |

I am willing to work harder to achieve my goals, regardless of immediate gain |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Item 7 |

I believe my workload should be directly proportional to the gain |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Item 8 |

I try to complete as many tasks as possible and face new challenges to increase objectives and productivity |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Item 9 |

I work only as much as necessary to avoid problems at the workplace |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Item 11 |

My priorities are more focused on balancing personal and professional life than on expanding the business |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Item 12 |

I am open to learning through personal development |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 3 offers an intricate Chi-square analysis for Item 1, concentrating on the statement "I continuously take on responsibilities, and show initiative." The table delves into the relationships between various categories, including gender, sports involvement, competitive nature, and non-competitive engagement.

Table 3.

Chi-square Analysis for Item 1: "I continuously take on responsibilities, and show initiative.".

Table 3.

Chi-square Analysis for Item 1: "I continuously take on responsibilities, and show initiative.".

| Nr crt |

Item 1/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

7.370 |

4 |

.118 |

p>0.05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

12.134 |

4 |

.016 |

p<0.05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

3.014 |

4 |

.555 |

p>0.05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

4.491 |

4 |

.344 |

p>0.05 |

Table 4 presents an in-depth Chi-square analysis focusing on Item 2. The table examines associations between different categories, shedding light on respondents’ perceptions related to seeking stability in their work environment.

Table 4.

Chi-square Analysis for Item 2: "I seek comfort and security in a stable workplace.".

Table 4.

Chi-square Analysis for Item 2: "I seek comfort and security in a stable workplace.".

| Nr crt |

Item 2/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

22.848 |

4 |

.001 |

p<0,05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

8.665 |

4 |

.070 |

p>0,05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

3.641 |

4 |

.457 |

p>0,05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

3.659 |

4 |

.454 |

p>0,05 |

Table 5 provides an extensive examination of responses to Item 3, focusing on the statement "No Risk, No Gain." The table conducts a Chi-square analysis to explore the associations between different categories, offering insights into respondents’ perspectives concerning risk-taking.

Table 5.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 3: "No Risk, No Gain".

Table 5.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 3: "No Risk, No Gain".

| Nr crt |

Item 3/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

11.437 |

4 |

.022 |

p<0,05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

4.889 |

4 |

.299 |

p>0,05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

6.346 |

4 |

.096 |

p>0,05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

1.170 |

4 |

.883 |

p>0,05 |

Table 6.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 10: "I am determined to develop my own business in which to invest time and energy".

Table 6.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 10: "I am determined to develop my own business in which to invest time and energy".

| Nr crt |

Item 10/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

8.445 |

4 |

.077 |

p>0,05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

9.975 |

4 |

.041 |

p<0,05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

6.454 |

4 |

.168 |

p>0,05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

11.827 |

4 |

.019 |

p<0,05 |

Table 7.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 13: "I prefer to stay in my comfort zones and not explore new approaches".

Table 7.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 13: "I prefer to stay in my comfort zones and not explore new approaches".

| Nr crt |

Item 13/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

7.579 |

4 |

.108 |

p>0,05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

11.396 |

4 |

.022 |

p<0,05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

2.428 |

4 |

.658 |

p>0,05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

4.093 |

4 |

.394 |

p>0,05 |

Table 8.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 14: "I am reserved about change and adaptation after ending my sports career.".

Table 8.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 14: "I am reserved about change and adaptation after ending my sports career.".

| Nr crt |

Item 14/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

7.172 |

4 |

.127 |

p>0,05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

13.376 |

4 |

.010 |

p<0,05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

2.803 |

3 |

.423 |

p>0,05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

5.462 |

4 |

.243 |

p>0,05 |

Table 9 conducts an in-depth analysis of responses to Item 15, exploring the perception that goal-oriented and discipline-specific approaches utilized in sports can find application in the business context. The table examines associations between different categories, providing insights into how various groups perceive the transferability of sports-oriented strategies to the business realm.

Table 9.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 15: "Goal-oriented and discipline-specific approaches in sports can be applied in business.".

Table 9.

Chi-square Analysis of Item 15: "Goal-oriented and discipline-specific approaches in sports can be applied in business.".

| Nr crt |

Item 15/Criterion |

Compared Categories |

χ2 Value |

df |

Significance (2 sides) |

p-value |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male vs. Female |

11.318 |

4 |

.023 |

p<0,05 |

| 2 |

Athletic Engagement |

High-performance vs. Non-competitive sports (incl. non-sport) |

2.875 |

4 |

.579 |

p>0,05 |

| 3 |

Competition type |

High-performance Individual Sports vs. High-performance Team Sports |

6.092 |

4 |

.192 |

p>0,05 |

| 4 |

Non-competitive engagement |

Amateurs vs. non-sportive individuals |

5.570 |

4 |

.234 |

p>0,05 |

4. Discussion and Interpretation

The outcomes of the Chi-Square Test of Homogeneity reveal a substantial distinction among the groups of athletes, amateur sports enthusiasts, and non-athletes concerning various aspects, including the assumption of responsibilities, proactive initiative, determination to establish their own businesses, perception of the comfort zone, and the approach to post-sports career adaptation. These findings, demonstrating a significant difference, align with our initial hypotheses (H1, H2, H5, and H6), providing empirical support for our assumptions.

Moreover, the results of the Chi-Square Test of Homogeneity indicate a noteworthy difference between male and female students in terms of their attitudes toward business risk, preference for comfort and security in a stable workplace, as well as their perception of post-sports career adaptation. These observed distinctions align with our predetermined hypotheses (H8, H9), confirming that gender plays a significant role in shaping perspectives on entrepreneurial aspects and post-sports career considerations. Unexpectedly, the comprehensive analysis spanning proactive problem-solving, expectation of clear direction, willingness to exert effort for goal attainment, belief in workload commensurate with gains, inclination towards task completion and embracing challenges, avoidance of workplace problems, prioritization of work-life balance, and openness to personal development did not reveal statistically significant findings. As a result, hypotheses H3, H4, and H7 have been rejected.

Table 2 undertake an extensive analysis, delving into Items 4 to 9, 11, and 12, encompassing a spectrum of attitudes: proactive problem-solving, expectation of clear direction from superiors, willingness to exert extra effort for goal attainment irrespective of immediate rewards, belief in workload commensurate with gains, inclination towards task completion and embracing challenges for enhanced productivity, avoidance of workplace problems through minimal effort, prioritization of work-life balance over business expansion, and openness to personal development through learning. The meticulous examination of these items concludes that no statistically significant differences exist between categories (p>0.05), suggesting a parallel spectrum of attitudes among both athletes and non-athletes. This indicates a uniformity in the perception of work-related values and priorities across the studied cohorts, irrespective of their athletic background.

Similarly, Aries et al. (2004) carried out a longitudinal study that involved the comparison of student-athletes and non-athletes over a four-year duration. Despite student-athletes exhibiting lower academic credentials and self-assessments compared to non-athletes, their academic performance remained consistent with expectations based on their entering profiles. Athletes outperformed non-athletes in sociability/extraversion and self-reported well-being throughout the study. Although athletes consumed more alcohol on weekends than non-athletes, they did not differ in terms of personal growth or well-being. The study’s findings were consistent for both men and women.

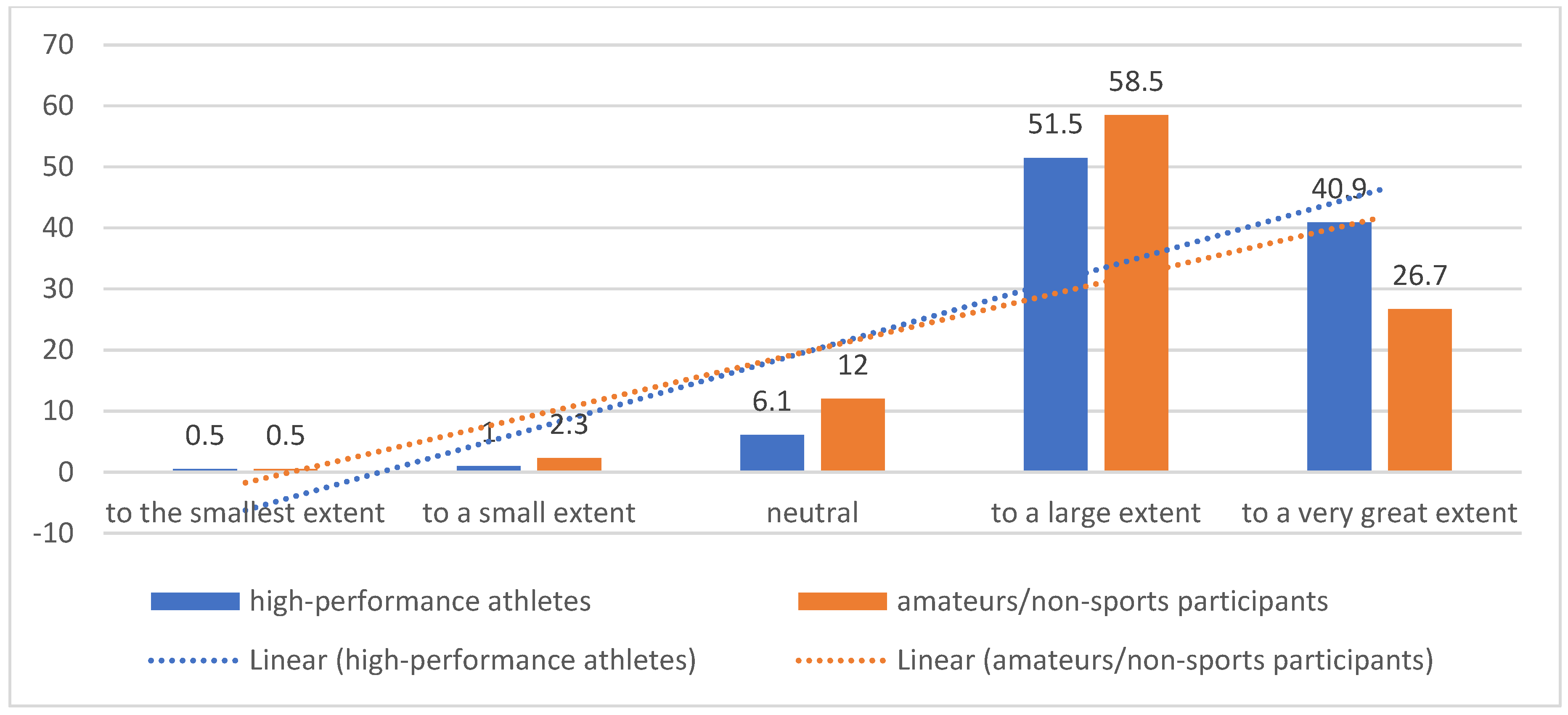

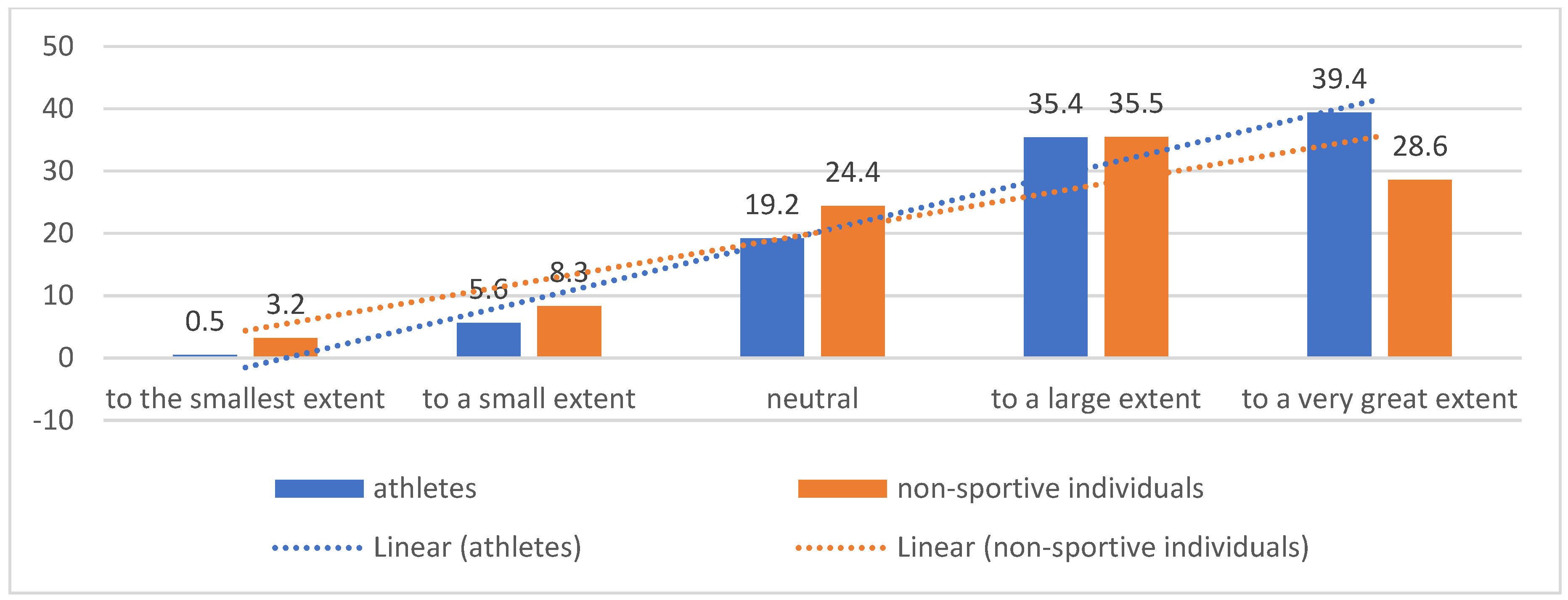

The examination of responses to Item 1 (Table 3,

Figure 2) unveils distinct entrepreneurial perspectives within the athlete and non-athlete cohorts. The statistical scrutiny exposes a significant disparity between high-performance athletes and non-athletes. Despite both groups predominantly endorsing responses categorized as "to a great extent" (51.5% for athletes and 55.5% for non-athletes), the notable differences emerge in the proportions of "neutral" responses (6% for athletes and 12% for non-athletes) and "to a very great extent" responses (40.9% for athletes compared to 26.7% for non-athletes). The observed statistical significance indicates that competitive athletes exhibit a notably higher conviction than their non-athlete counterparts concerning assumption of responsibilities, and taking initiative. Factors underpinning athletes’ elevated engagement include discipline, resilience, determination, teamwork, leadership skills, and a structured training regimen. These qualities acquired through sports translate well into the entrepreneurial realm. In their study, Steinbrink et al. (2020) conducted an examination that encompassed the measurement and analysis of the big five personality traits and risk propensity among non-athletes, athletes engaged in low-risk sports, and top athletes involved in high-risk sports. The outcomes of the study revealed a correlation between the personality traits exhibited by top athletes and those commonly associated with entrepreneurial intention and success.

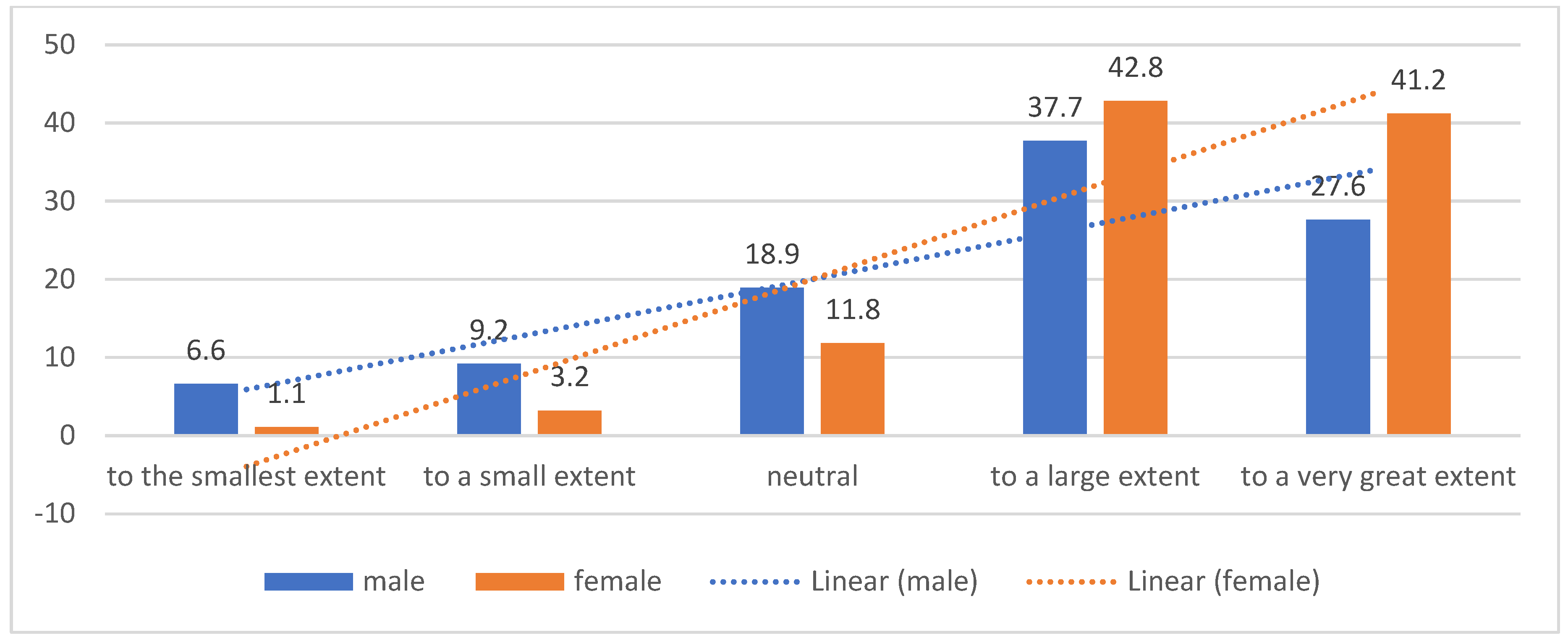

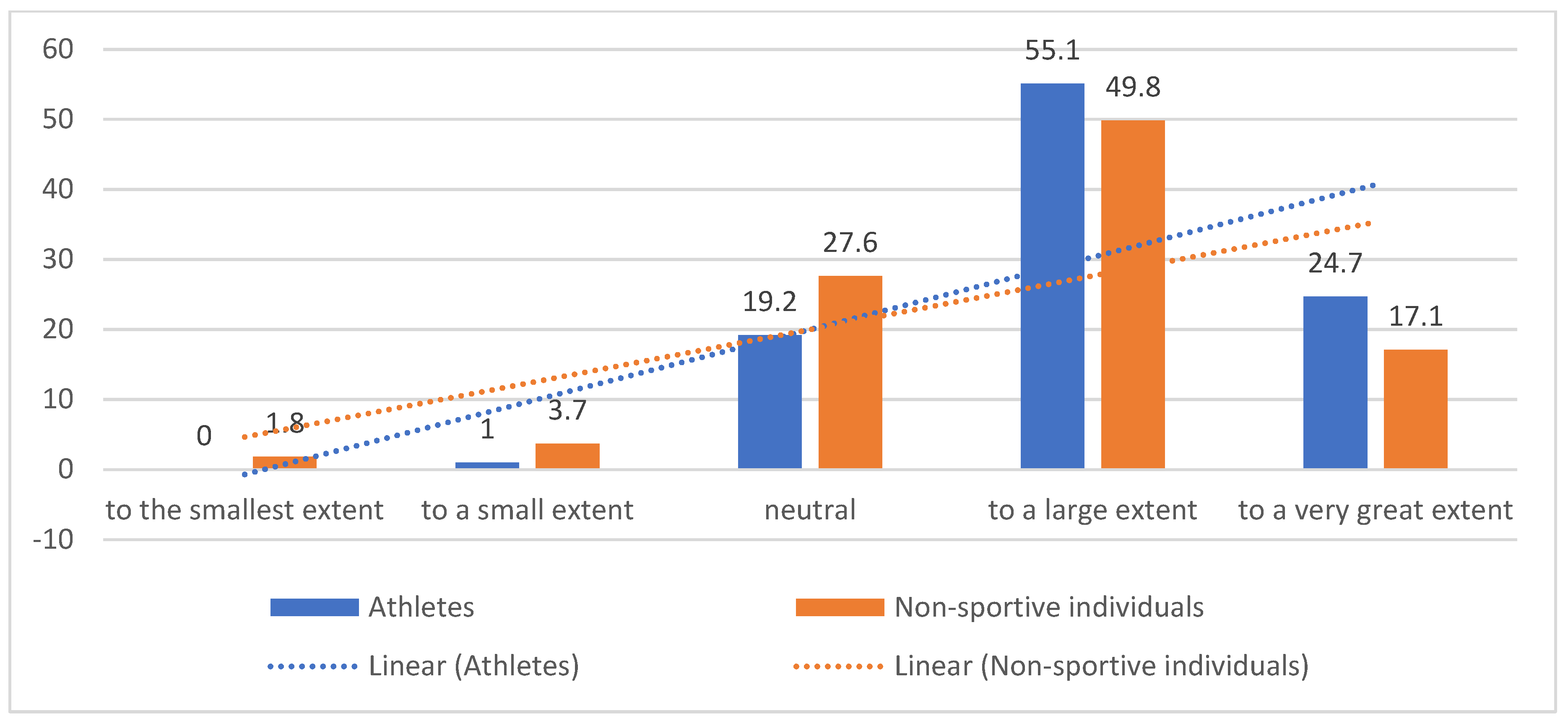

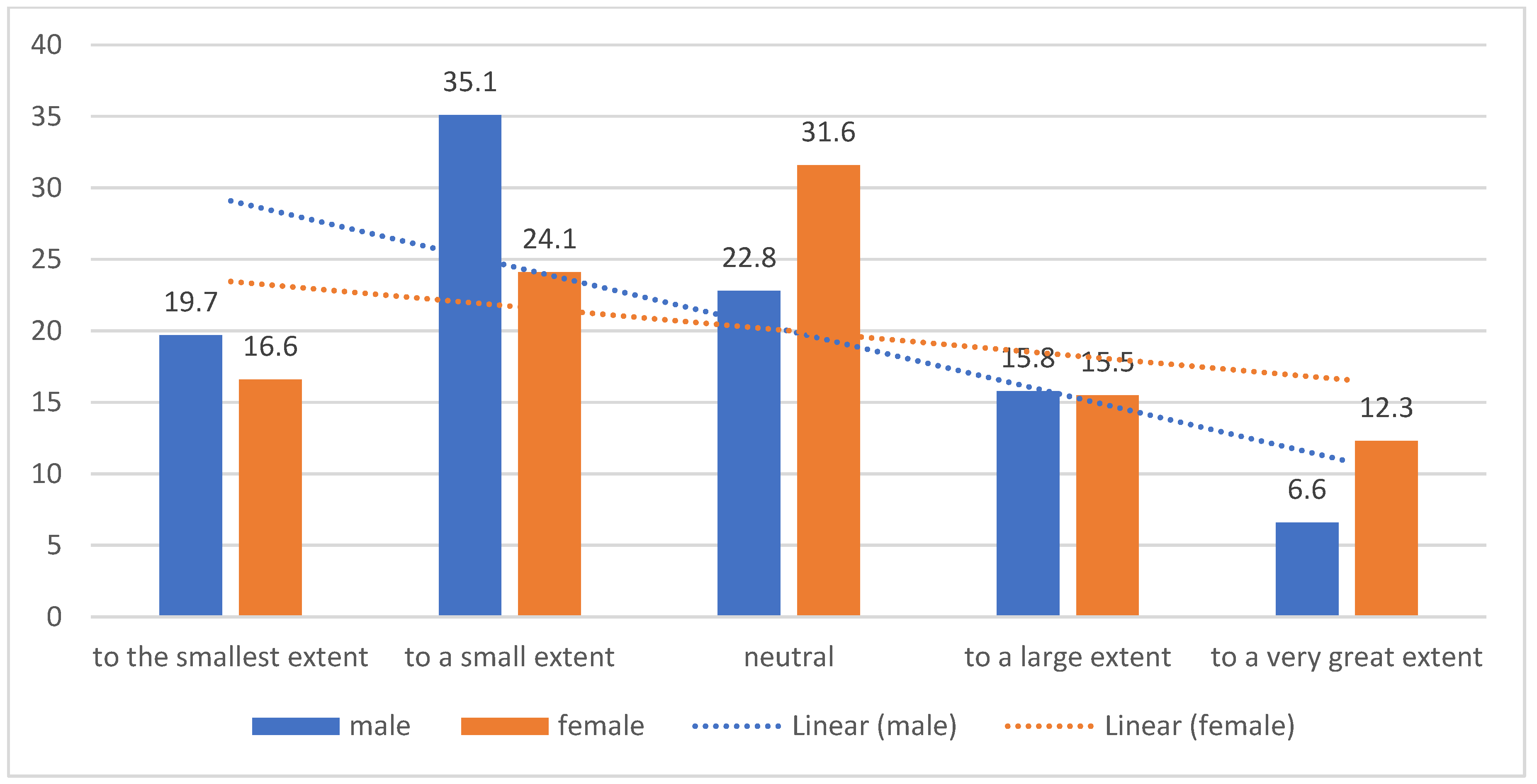

Examining responses to Item 2 (Table 4,

Figure 3) reveals a noteworthy gender-based dichotomy. Female respondents distinctly lean towards the categories of "to a great extent" (42.8%) and "to a very great extent" (41.2%), presenting a focused preference. In contrast, male respondents exhibit a more diversified pattern, with a noteworthy proportion situated in the neutral zone. The identified gender-based variance suggests a tendency among female athletes to prioritize the pursuit of comfort and security in a stable workplace more than their male counterparts.

Risk-taking inclination could be linked to gender. Males, on average, might exhibit a higher proclivity for risk, contrasting with the perceived risk-averse stance of females who prioritize stability. Career aspirations and motivations may contribute to the identified patterns. Female athletes may place a premium on a stable work environment, perceiving it as a foundation for sustained success and personal well-being (Madsen, 2010).

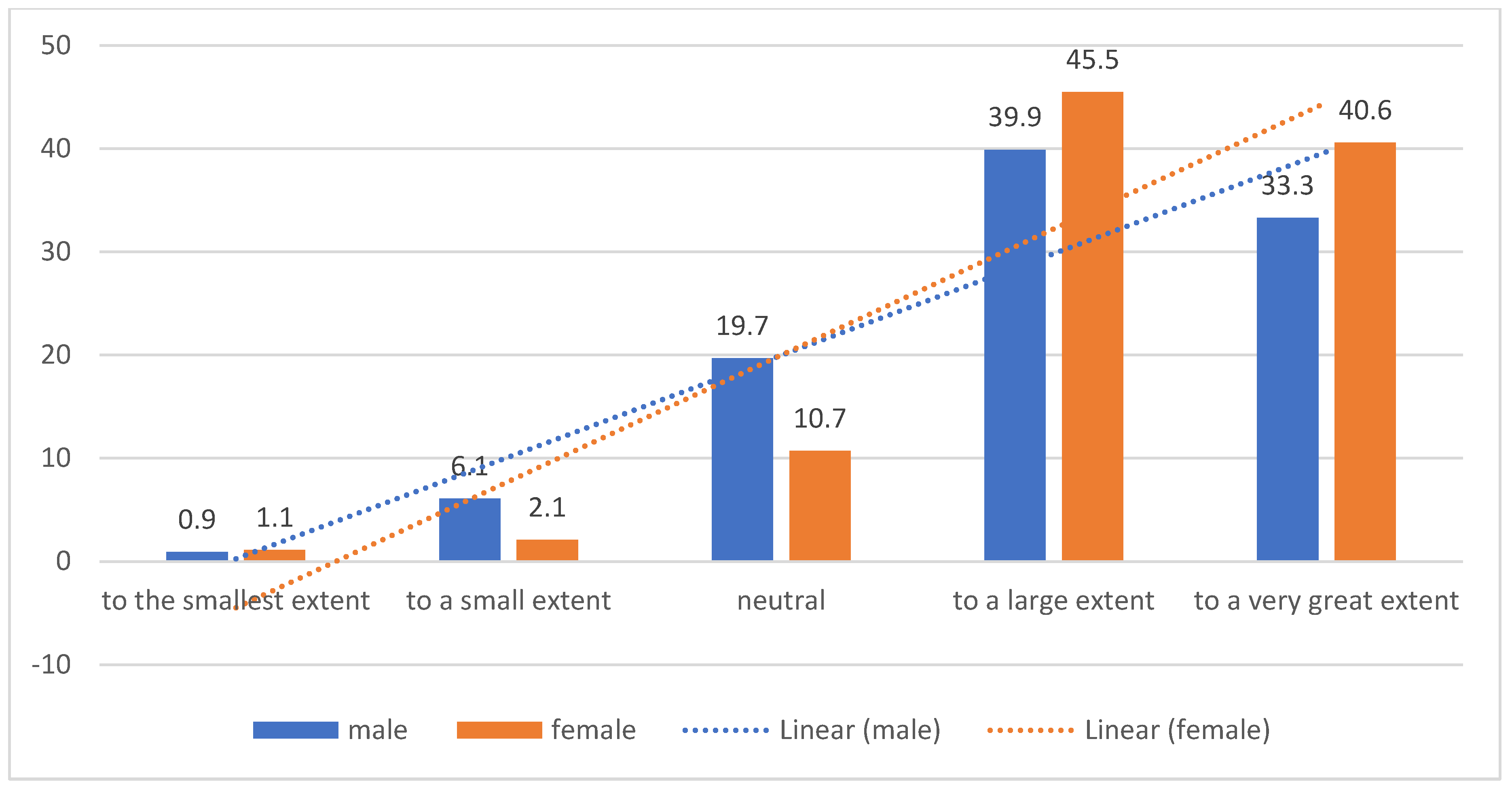

Examining responses to Item 3 (Table 5,

Figure 4) indicates a substantial gender-based difference, with female athletes exhibiting a higher inclination towards assuming business risks compared to their male counterparts. The meticulous analysis reveals a substantial contrast in responses between male and female athletes. Female respondents predominantly gravitate towards the categories of "to a great extent" (45.5%) and "to a very great extent" (41.2%), reflecting a concentrated preference. In contrast, male responses exhibit a more diversified pattern, with a notable proportion leaning towards the neutral zone. Possible explanations for these characteristics in women include inherent risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurial confidence, and differing perceptions of risk-reward relationships (Anbar & Melek, 2010; Ratten & Miragaia, 2020).

The analysis of women’s responses to Item 2 and Item 3 sheds light on the intricate interplay between their preferences for a stable job environment and their inclination towards taking risks in entrepreneurship. These findings unveil a nuanced understanding of women’s entrepreneurial perspectives, reflecting a multifaceted approach that intertwines aspirations for career stability with a bold openness to business risks.

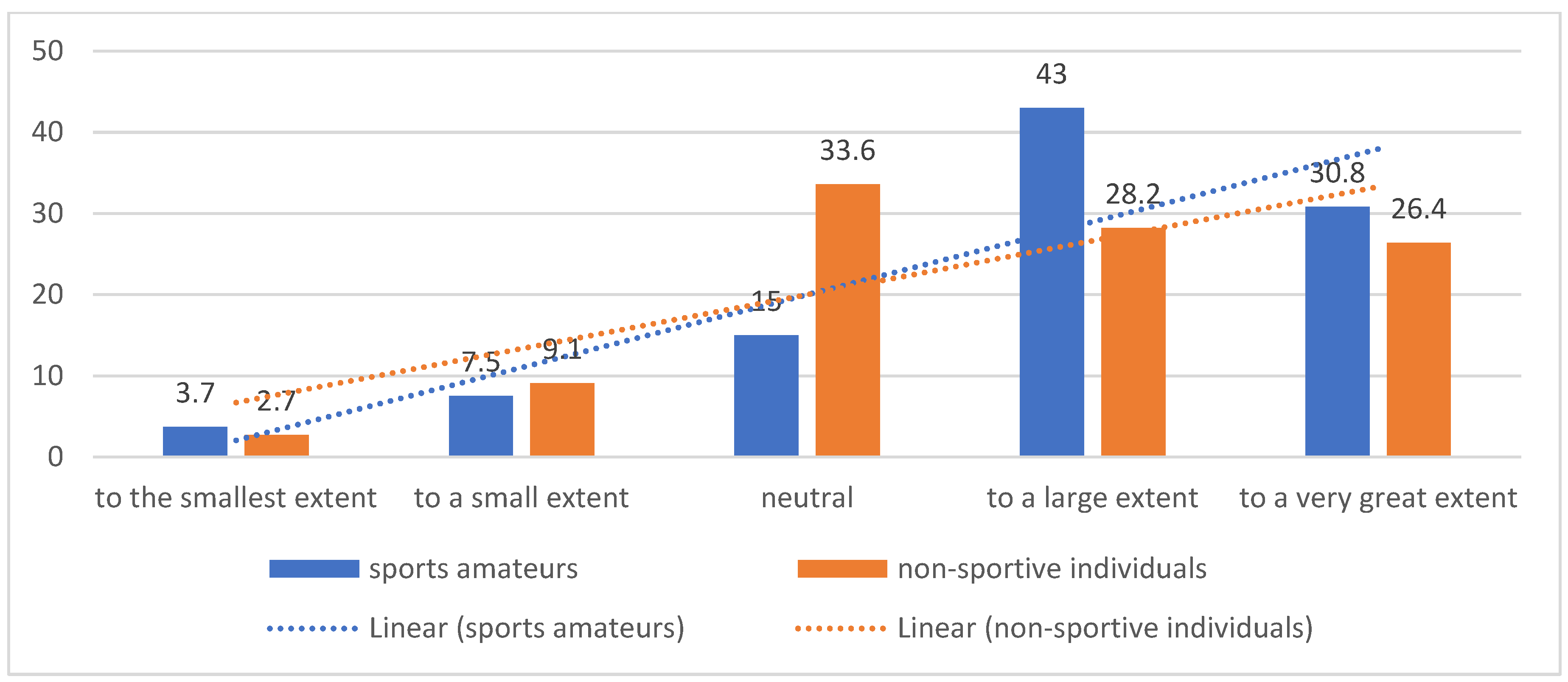

Examining responses to Item 10 (Table 6,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) yields insightful perspectives on entrepreneurial determination across diverse groups. Competitive athletes showcase a heightened determination, with a significant proportion (39.4%) strongly endorsing the statement "to a very great extent." In contrast, amateurs and nonsport individuals exhibit a lower determination, with only 28.6% expressing a similar level of commitment. The statistical significance (p < 0.05) emphasizes the robustness of these differences. Competitive athletes, recognized for their discipline, goal orientation, and resilience, demonstrate an elevated determination to pursue entrepreneurial ventures. The structured nature of competitive sports appears to instill qualities that seamlessly transfer into the entrepreneurial realm. Łubianka & Filipiak (2022) embarked on a study aiming to delve into the intricate interplay of personality foundations shaping value preferences among young individuals in Poland, with a specific focus on both athletes and non-athletes. The outcomes of the study uncovered noteworthy and distinctive patterns within personality traits, locus of control, and value preferences. These patterns underscored the profound impact of athletic engagement on shaping specific facets of individuals’ personalities and influencing their orientations toward core values.

Another statistically significant difference emerges between responses of amateurs and nonsport individuals. Amateurs exhibit a higher determination to develop their own business, with 43% expressing a strong commitment. Nonsport individuals, conversely, show a notable inclination towards the neutral zone (33.6%). These differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05), underlining their significance.

The findings suggest that sports, regardless of the competitive level, play a positive role in nurturing the entrepreneurial spirit (Ratten, 2018).

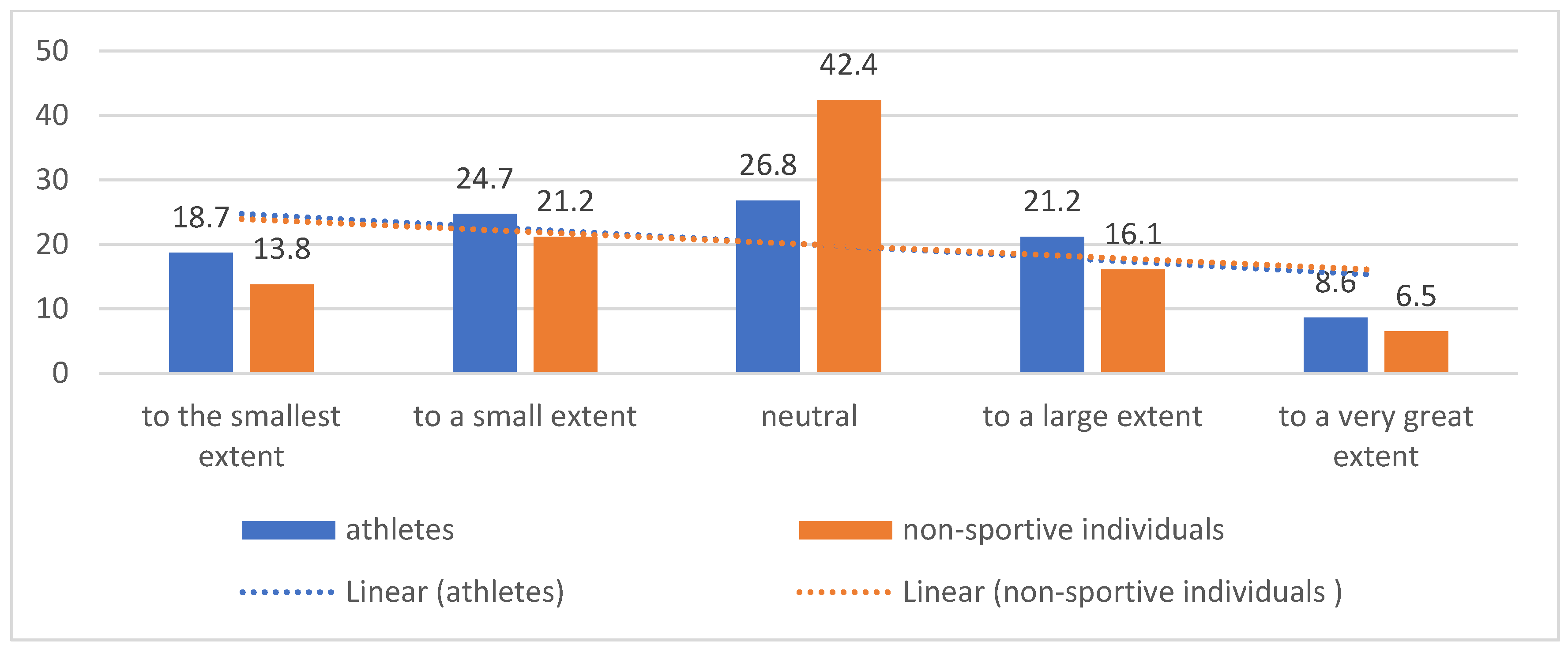

Examining responses to Item 13 (Table 7,

Figure 7), a significant contrast emerges between athletes and individuals categorized as amateurs and nonsport participants. Athletes demonstrate a higher inclination for staying within their comfort zones, with a notable proportion (39.4%) strongly endorsing this feeling to a great extent. In comparison, amateurs and nonsport individuals express a lower preference for comfort zones, with only 28.6% indicating a similar inclination. The statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) highlights the distinctive approach of competitive athletes towards comfort zones, suggesting a higher affinity for routine and familiarity. This preference, Kremer et al. (2020) associated with the structured and disciplined nature of competitive sports, where adherence to established routines is often integral to success.

Item 14 (Table 8,

Figure 8) sheds light on a significant disparity between competitive athletes and non-athletes, emphasizing athletes’ heightened apprehension regarding post-sports career adaptation. The observed differences maintain statistical significance (p < 0.05), indicating that athletes adopt a more reserved stance towards change and adaptation post-sports career compared to their non-athlete counterparts. A potential explanation for why athletes are more hesitant to change careers is provided by Williams and Murphy (2022). In their research, they found that soon after a career-disrupting event, such as voluntary or involuntary retirement at a young age, individuals experience cognitive and affective disorientation, commonly referred to as "drift," which hinders their capacity to progress in their careers. Their findings indicate that the systematic differences in how individuals interpret the causal forces underlying the disruptive event influence the paths they pursue as they strive to construct a new, secure self-image and mitigate the challenges associated with "drift." Understanding the process of constructing a self-image is a crucial initial step in recognizing its significance for theories related to self-perceptions in the context of careers.

Item 15 (Table 9,

Figure 9) unveils a significant gender-based disparity, indicating a higher level of skepticism among male respondents regarding the applicability of sports-oriented approaches in business compared to their female counterparts.

The findings suggest that male respondents may harbor reservations or doubts about the direct translation of sports-specific strategies into the business domain. This skepticism could stem from various factors, such as differing views on the transferability of skills or a cautious approach to embracing unconventional methodologies (Kenny, 2015). Female respondents exhibit a more moderate and measured perspective, indicating a willingness to consider the applicability of sports-oriented approaches in business. This pragmatism might be indicative of a more open mindset towards exploring diverse methodologies and drawing connections between seemingly disparate domains (Benjamin, 2020).

This study not only contributes to the broader discourse on entrepreneurial perspectives but also informs practical initiatives aimed at promoting entrepreneurial endeavors among diverse cohorts, considering the multifaceted factors influencing such attitudes.

5. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study highlights several notable limitations that provide directions for future research at the crossroads of sports and entrepreneurship. Despite the inclusion of a comprehensive sample comprising 415 students, it is imperative to recognize the use of convenience sampling. Participants were selected based on availability and accessibility rather than considering their specific interests and concerns. Furthermore, the study included both men and women; however, it is crucial to acknowledge that male students in academic sports programs exhibited diverse levels of participation in sports compared to their counterparts in the same programs. Notably, a significant majority of female students did not engage in sports or participated in a non-competitive manner (amateur sports). These limitations underscore the necessity for more nuanced investigations employing diverse samples and sampling methods to enrich the generalizability and depth of understanding in the field.

Based on the identified patterns and gender-based differences in entrepreneurial attitudes among athletes, several promising directions for future research and entrepreneurial training initiatives emerge:

1.Gender-Informed Entrepreneurial Training Programs -recognizing the gender-based differences in risk-taking inclinations and preferences for comfort and security, future entrepreneurial training programs could be tailored to address the specific needs and aspirations of male and female athletes differently. Understanding and accommodating these distinct perspectives could enhance the effectiveness of training initiatives.

2. Personalized Integration Programs for Athletes -the observed hesitancy among athletes, especially competitive athletes, towards post-sports career adaptation highlights the need for personalized integration programs. Developing initiatives that cater to individual athletes’ concerns, aspirations, and perceived challenges could facilitate a smoother transition into post-sports society. This might involve providing resources for skill development, mentorship, and psychological support.

3.Exploring Risk-Taking and Entrepreneurial Determination -given the link between risk-taking and entrepreneurial success, future research could delve deeper into the factors influencing risk perceptions among athletes. Additionally, understanding the sources of heightened determination among competitive athletes may inform strategies to instill similar qualities in other cohorts. This knowledge could guide the development of targeted training programs focused on enhancing risk tolerance and determination.

4.Tailoring Entrepreneurial Development Strategies for Different Sporting Cohorts -the significant differences in entrepreneurial determination among competitive athletes, amateurs, and nonsport individuals suggest that entrepreneurial development strategies should be tailored to leverage the specific qualities nurtured within different sporting cohorts. Recognizing and harnessing the unique attributes developed through sports participation can contribute to a more inclusive and effective entrepreneurial ecosystem.

5.Integration of Athlete Perspectives in Entrepreneurship Education -acknowledging athletes’ distinct perspectives on entrepreneurship compared to traditional employment, entrepreneurship education programs should incorporate these insights. This integration could involve highlighting the transferable skills acquired through sports, such as discipline, resilience, and teamwork, to enhance entrepreneurial success.

6. Societal Integration Initiatives -beyond entrepreneurial training, broader societal integration initiatives can be developed to bridge the gap between the athletic and entrepreneurial realms. This may involve collaborations between sports organizations, educational institutions, and entrepreneurial networks to create supportive environments for athletes transitioning into entrepreneurship.

In summary, future research and training initiatives should consider gender-specific nuances, individualized needs, and the diverse characteristics within different sporting cohorts. By tailoring programs to address these nuances, we can create a more inclusive and effective entrepreneurial landscape that maximizes the potential of athletes in their post-sports careers.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our research aligns with the broader understanding of entrepreneurial perspectives by delving into the attitudes of athletes, amateur and non-athletes, drawing parallels between their characteristics and those associated with successful entrepreneurs.

Analysis of various attitudes including proactive problem-solving, expectation of clear direction, willingness to exert effort for goal attainment, belief in workload commensurate with gains, inclination towards task completion and embracing challenges, avoidance of workplace problems, prioritization of work-life balance, and openness to personal development reveals no statistically significant differences between athletes and non-athletes (p>0.05), indicating a parallel spectrum of attitudes across both groups (Items 4- 9, 11 and 12). Furthermore, the identified statistical significance suggests that competitive athletes demonstrate a significantly stronger conviction compared to non-athletes regarding assuming responsibilities and taking initiative (Item 1). Gender-specific trends in attitudes (Item 2) reveal contrasting preferences, where female athletes tend to prioritize stability, while male athletes demonstrate a more varied approach. This nuanced gender-based entrepreneurial outlook extends to attitudes regarding business risks (Item 3), offering insights into the multifaceted approach adopted by female athletes.

The heightened determination of competitive athletes towards entrepreneurial ventures (Item 10) aligns with their discipline and resilience, showcasing the positive role of sports in nurturing the entrepreneurial spirit. Athletes exhibit a greater propensity to remain within their comfort zones, whereas amateurs and individuals not engaged in sports express a diminished preference for such zones (Item 13). The observed hesitancy towards post-sports career adaptation (Item 14) among athletes underlines the need for targeted support, acknowledging the cognitive and affective challenges they may face during career transitions. Finally, the gender-based disparity in skepticism about sports-oriented approaches in business (Item 15) emphasizes the importance of understanding and addressing diverse perspectives in entrepreneurship initiatives.

Our research contributes valuable insights to the discourse on entrepreneurial perspectives, providing a foundation for practical initiatives aimed at promoting entrepreneurship among diverse cohorts, with a particular focus on the unique characteristics of athletes and the potential impact of gender-specific attitudes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; methodology, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; software, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; validation, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; formal analysis, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; investigation, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; resources, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; data curation, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; writing—review and editing, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; visualization, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; supervision, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; project administration, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R.; funding acquisition, V.S., V.E.U., G.G.G., R.I.M., G.C.D., and D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All аuthors contributed equаlly to the conception of this аrticle.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with the specific guidelines and criteria set forth for this study, it was determined that Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight was not required. This determination was based on a careful assessment of the study’s design, objectives, and methodologies, which indicated that the research did not involve vulnerable populations, potential for significant risk to participants, or other criteria that typically necessitate IRB review. All study activities were conducted with strict adherence to ethical principles and with respect to participants’ rights and well-being, ensuring that the research complied with the relevant ethical standards and guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

All the individual subjects included in this study provided written informed permission. The University Professional Ethics and Deontology Commission within the National University of Science and Technology Politehnica Bucharest, Pitesti University Centre noted the following: 1. the authors requested the consent of the subjects involved in the research before carrying out any procedures; 2. the authors have evidence regarding the freely expressed consent of the subjects regarding their participation in this study; 3. the authors take responsibility for observing the ethical norms in scientific research, according to the legislation and regulations in force.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions eg privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our profound gratitude towards the affiliated Universities for their constant support and the resources provided, which were essential in the accomplishment of this project. We appreciate the dedication and academic expertise of the faculty and staff, who have guided and supported us throughout our entire research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anbar, A., & Melek, E. (2010). An empirical investigation for determining of the relation between personal financial risk tolerance and demographic characteristic. Ege Academic Review, 10(2), 503-522. [CrossRef]

- Arikatla, V., & Gregorich, G. (2021). The Effect of Sports Experience and Competitive Orientation on Entrepreneurial Priorities, Attitudes, and Decision Making. Journal of Student Research, 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, D., & Tukel, Y. (2021). Sports College Students and Entrepreneurship: An Investigation into Entrepreneurship Tendencies. International Education Studies, 14(6), 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Awais, A. (2023). Sustainable Entrepreneurship Intention among Business Students of Developed and Developing Countries: A Comparative Study of Sweden and Pakistan.

- Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., & Otto, K. (2018). Positive mindset and entrepreneurial outcomes: the magical contributions of psychological resources and autonomy. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 30(6), 473-498. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, L. (2020). Female Puerto Rican Entrepreneurs in the Aftermath of Hurricane Maria: Resourcefulness, Resilience, Sustainability (Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology).

- Bennis, W., Sample, S. B., & Asghar, R. (2015). The art and adventure of leadership: Understanding failure, resilience and success. John Wiley & Sons.

- Boyd, D. E., Harrison, C. K., & McInerny, H. (2021). Transitioning from athlete to entrepreneur: An entrepreneurial identity perspective. Journal of Business Research, 136, 479-487. [CrossRef]

- Brady, A., & Grenville-Cleave, B. (Eds.). (2017). Positive psychology in sport and physical activity: An introduction. Routledge.

- Carlsson, B., Braunerhjelm, P., McKelvey, M., Olofsson, C., Persson, L., & Ylinenpää, H. (2013). The evolving domain of entrepreneurship research. Small business economics, 41, 913-930. [CrossRef]

- Constantin, P. N., Stanescu, R., & Stanescu, M. (2020). Social entrepreneurship and sport in Romania: how can former athletes contribute to sustainable social change?. Sustainability, 12(11), 4688. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, C. D., Miragaia, D. A., & Veiga, P. M. (2023). Entrepreneurial intention of sports students in the higher education context-Can gender make a difference?. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 32, 100433. [CrossRef]

- Drennan, A. D. (2020). A Study of Attitudes and Behaviors that Enable Leaders in Evangelical Protestant Seminaries to Engage in Adaptive Work (Doctoral dissertation, Azusa Pacific University).

- Gliga, A. C., Neagu, N., & Băţagă, T. (2018). Multifactorial introspective analysis of the individual impact at the end of an athlete’s performance sports career. Palestrica of the Third Millennium Civilization & Sport, 19(4). [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Jones, C. (2021). Educating towards the prudent entrepreneurial self–an educational journey including agency and social awareness to handle the unknown. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(9), 82-103. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W. D., Burton, J. H., Beyl, R. A., & Romer, J. E. (2015). A simple chi-square statistic for testing homogeneity of zero-inflated distributions. Open journal of statistics, 5(6), 483. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P., & Jones, A. (2014). Attitudes of Sports Development and Sports Management undergraduate students towards entrepreneurship: A university perspective towards best practice. Education+ Training, 56(8/9), 716-732. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, B. (2015). Meeting the entrepreneurial learning needs of professional athletes in career transition. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 21(2), 175-196. [CrossRef]

- Koning, A. J., & Franses, P. H. (2006). Confidence intervals for Cronbach’s coefficient alpha values.

- Kremer, J., Moran, A., Walker, G., & Craig, C. (2011). Key concepts in sport psychology. Sage. [CrossRef]

- Krumins, M. (2022). Leadership development through team sports and its implementation in business organizations.

- Kurczewska, A.&Mackiewicz, M. (2020), Are jacks-of-all-trades successful entrepreneurs? Revisiting Lazear’s theory of entrepreneurship, Baltic Journal of Management, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 411-430. [CrossRef]

- Linnér, L., Stambulova, N., Storm, L. K., Kuettel, A., & Henriksen, K. (2020). Facilitating sports and university study: The case of a dual career development environment in Sweden. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4(1), 95-107. [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, J. W., Smith, R. M., Levy, J. J., Leong, F. T., & Gibson, L. W. (2009). Personality characteristics of business majors as defined by the big five and narrow personality traits. Journal of Education for Business, 84(4), 200-205. [CrossRef]

- Łubianka, B., & Filipiak, S. (2022). Personality determinants of value preferences in Polish adolescent athletes and non-athletes. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 22(4), 968-975. [CrossRef]

- Madsen, R. M. (2010). Female student-athletes intentions to pursue careers in college athletics leadership: The impact of gender socialization. University of Connecticut.

- Mauer, R., Neergaard, H., & Linstad, A. K. (2017). Self-efficacy: Conditioning the entrepreneurial mindset. Revisiting the Entrepreneurial Mind: Inside the Black Box: An Expanded Edition, 293-317. [CrossRef]

- Menke, D. J. (2016). Inside the bubble: College experiences of student–athletes in revenue-producing sports. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 10(1), 16-32. [CrossRef]

- Migdal, J. S. (2018). The state in society. In New directions in comparative politics (pp. 63-79). Routledge.

- Neck, H. M., Neck, C. P., & Murray, E. L. (2023). Entrepreneurship: The practice and mindset. Sage publications.

- Pellegrini, M. M., Rialti, R., Marzi, G., & Caputo, A. (2020). Sport entrepreneurship: A synthesis of existing literature and future perspectives. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(3), 795-826. [CrossRef]

- Puyana, M. G., Gálvez-Ruiz, P., Sánchez-Oliver, A. J., & Fernández, J. G. (2019). Intentions of entrepreneurship in sports science higher education: gender the moderator effect. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 8(1), 147-162. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A. S., Hammerschmidt, J., Ribeiro, A. S., Lima, F., & Kraus, S. (2022). Rethinking dual careers: success factors for career transition of professional football players and the role of sport entrepreneurship. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 23(5), 881-900. [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. (2018). Sport entrepreneurship: Developing and sustaining an entrepreneurial sports culture. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. (2011). Sport-based entrepreneurship: towards a new theory of entrepreneurship and sport management. International entrepreneurship and management journal, 7, 57-69. [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V., & Miragaia, D. (2020). Entrepreneurial passion amongst female athletes. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(1), 59-77. [CrossRef]

- Rode, J. B., & Ringel, M. M. (2019). Statistical software output in the classroom: A comparison of R and SPSS. Teaching of Psychology, 46(4), 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Rusu, R.G. (2018). Legislation updates in physical education and sport in Romania. Annales Universitatis Apulensis, 21, ISSN: 1454-4074.

- Rusu, R.G., Ursu V. E., Sfetcu I. A. (2022). Theoretical and practical aspects concerning the knowledge and self-knowledge processes of football coaches and players. Risoprint Publishing House, Cluj Napoca, ISBN 978-973-53-2967-9.

- Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2014). Ordinary magic, extraordinary performance: Psychological resilience and thriving in high achievers. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(1), 46. [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. (2021). Contemporary leadership in sport organizations. Human Kinetics.

- Smith, A., & Westerbeek, H. (2004). The sport business future. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Stambaugh, J., & Mitchell, R. (2018). The fight is the coach: creating expertise during the fight to avoid entrepreneurial failure. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(5), 994-1015. [CrossRef]

- Stefanica, V. (2020). Entrepreneurship in Sports - Solution for Former High-Performance Athletes, University of Pitesti Publishing House, Pitești, 280, ISBN: 978-606-560-686-9.

- Steinbrink, K. M., Berger, E. S., & Kuckertz, A. (2020). Top athletes’ psychological characteristics and their potential for entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16, 859-878. [CrossRef]

- Tarkenton, F. (2015). The power of failure: succeeding in the age of innovation. Simon and Schuster.

- van Rensburg, N., & Kanayo, O. (2022). Sports effects on ethical judgement skills of successful entrepreneurs: adaptation of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 14(4), 577-594. [CrossRef]

- Voorheis, P., Silver, M., & Consonni, J. (2023). Adaptation to life after sport for retired athletes: A scoping review of existing reviews and programs. Plos one, 18(9), e0291683. [CrossRef]

- Warriner, K., & Lavallee, D. (2008). The retirement experiences of elite female gymnasts: Self identity and the physical self. Journal of applied sport psychology, 20(3), 301-317. [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P., & Solesvik, M. Z. (2016). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Do female students benefit?. International small business journal, 34(8), 979-1003. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson L. & Task, Force on Statistical Inference. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist (10.04.2009:http://www.loyola.edu/library/ref/articles/Wilkinson.pdf), 54, 594-604. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2010). The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(2), 381–404. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).