Background

Problematic sleep, characterized by insufficient duration and poor quality, is pervasive among college students, manifesting in difficulties falling asleep, sleep disruption, irregular sleep schedules, and daytime sleepiness (Cellini et al., 2020; Lund et al., 2010; Schlarb et al., 2012). Research indicates that between 49% and 62% of college students classify as poor sleepers (Becker et al., 2018; Schmickler et al., 2023), with a majority sleeping less than the recommended 7-9 hours a night (Becker et al., 2018) and insomnia rates up to 30% (Carpi et al., 2022; Sivertsen et al., 2019). Lifestyle factors, such as increased screen time, substance misuse, and disruptions to circadian rhythms due to conflicts between academic obligations and social commitments are critical contributors to the sleep problems in this population (Hershner & Chervin, 2014; Wang & Bíró, 2021).

Unfortunately, the negative consequences of problematic sleep encompass not only academic concerns, but also physical and mental health. Studies have shown a notable decline in academic performance associated with sleep deprivation, as it impairs the ability to concentrate, memory consolidation, and cognitive function (Okano et al., 2019; Toscano-Hermoso et al., 2020). Furthermore, poor sleep is linked to adverse physical and mental outcomes, including an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Gawlik et al., 2019; Hershner & Chervin, 2014). Despite the significant role that healthy sleep plays in students’ academic performance, mental health, and overall well-being, the development and implementation of sleep educational programs aimed at raising awareness about the importance of good sleep habits and providing students with strategies to improve their sleep quality are rarely considered in higher educational institutions and public health agendas (Lim et al., 2023).

Several studies have investigated the effectiveness of educational programs on students’ sleep. However, while participation in such programs has been linked to heightened sleep knowledge and awareness of sleep-related topics, the effects on behavioral sleep outcomes, including sleepiness, sleep duration, or sleep hygiene, have been less uniform (Dietrich et al., 2016). In addition, existing programs show a great variety in the structure and delivery format of the programs (Dietrich et al., 2016), including psychology courses augmented with sleep-focused modules (Quan et al., 2013), self-help sleep promotion programs delivered through lecturers or researchers via email (Levenson et al., 2016), and comprehensive sleep education initiatives incorporating classroom lectures, web-based learning, and interactive discussions (The Science of Sleep and Dreams; Sleep (Gen Ed 1038)). These disparities likely influenced the participants’ level of engagement, both immediately and over the long term.

This pre-post study aimed to investigate the short-term impact of completing an online sleep education program on (1) sleep hygiene practices, (2) sleep quality, and (3) weekday and weekend sleep behaviors among college students.

Methods

Participants

During the fall semester of 2022, undergraduate and graduate students were recruited from a midsized public university in the Eastern United States and invited to participate in an online sleep education program (“Sleep 101”). Participation was voluntary, and open to all interested students enrolled at the university. Five $25 Amazon gift cards were raffled to participants who completed baseline and post-intervention assessments. The Mass General Brigham Human Research Office reviewed and approved this study.

Procedure

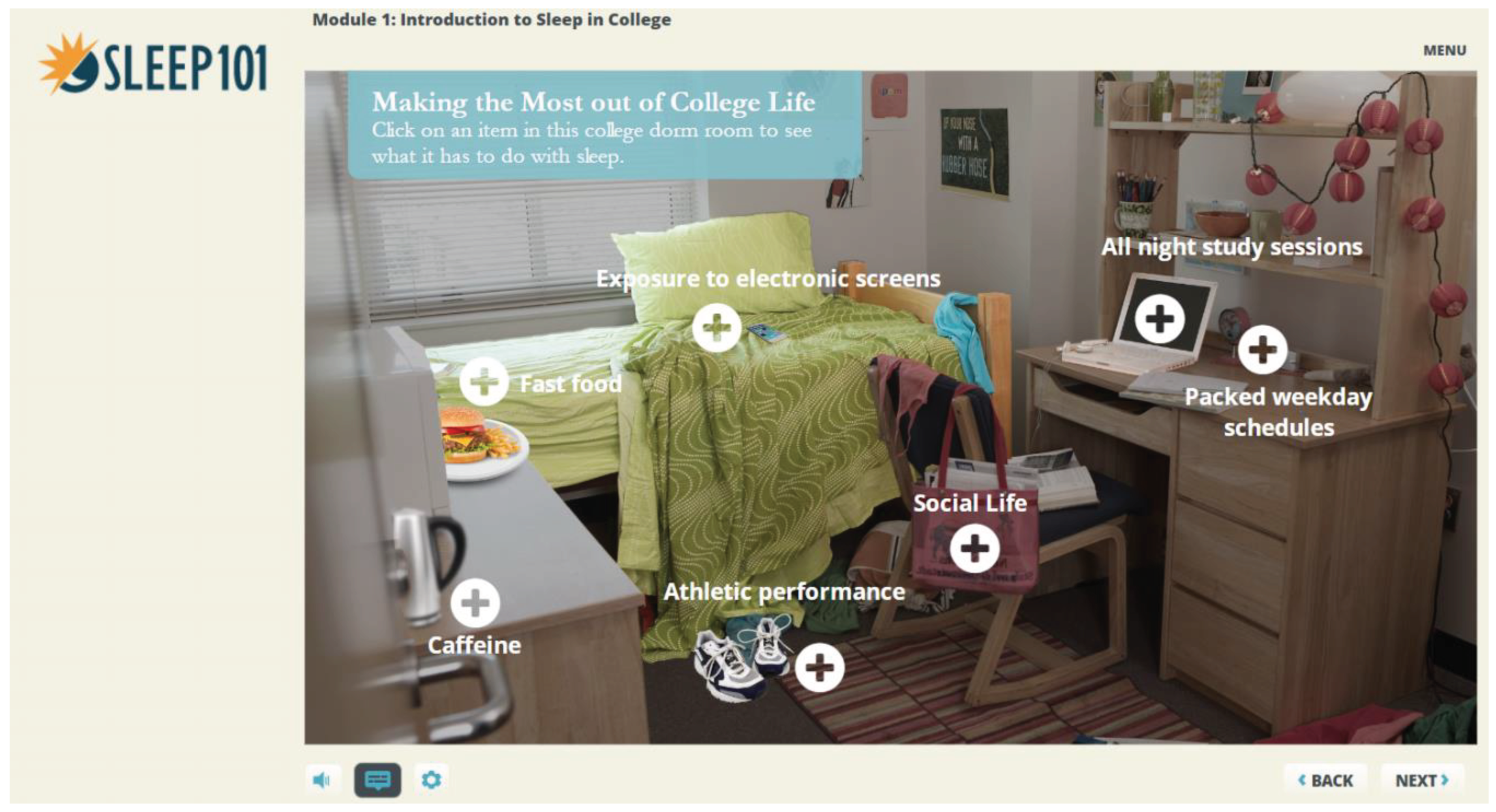

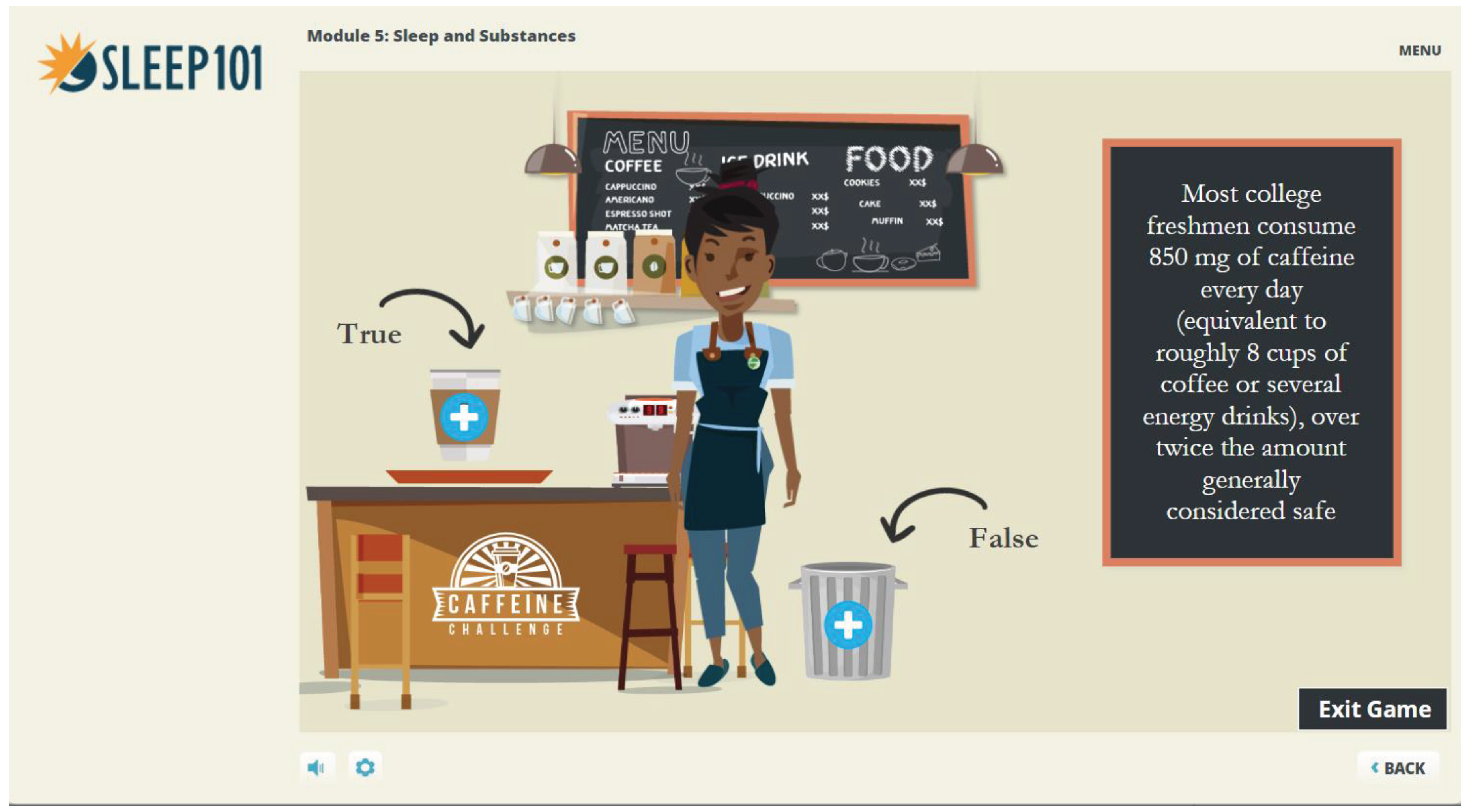

Sleep 101 is an interactive online course developed to educate college students about the importance of sleep. The program is designed to be completed in 45-60 minutes and is divided into several chapters that address basic sleep physiology, the impact of sleep on mood, academic and physical performance, the interactions between sleep and various substances, and common sleep disorders.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 provide exemplary insights into modules of the Sleep 101 program.

It was delivered through the university’s Learning Management System (LMS) and was open for seven weeks to be completed. Before starting the program (T0) and two weeks after Sleep 101 was closed (T1), participants were asked to complete online surveys using EFS Survey Unipark (Tivian XI GmbH, Cologne, Germany). A self-generated identification code was used to match T0 and T1 survey responses.

Measures

Sample Characteristics

At baseline, general demographic information using standardized questions was assessed, including gender, age, year of education, current living situation, and prior participation in a sleep education program.

Sleep Behavior

Weekday and weekend sleep behavior, including bed and wake times, sleep duration, sleep latency, and sleep quality during the past two weeks, was examined at both assessments. At post-intervention, students were asked to report behavior changes after participating in Sleep 101, including (1) changes to my daily routines or environment; (2) pulling all-nighters; (3) drowsy driving; (4) being confident to maintain changes to improve their sleep in the next two months.

Sleep Hygiene Behavior

We used the Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI) as a self-reported measure to assess students’ sleep hygiene practices (Mastin et al., 2006). The scale comprises 13 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale indicating the frequency of behaviors ranging from never (0) to always (4). Items are added to a final score, with higher numbers representing more maladaptive sleep hygiene practices. In previous studies, the SHI has shown adequate validity (Cronbach α of .66) and good test-retest reliability (r = .71).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline differences between non-completers and completers were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney-U-Test for non-parametric data. To determine the impact of participating in Sleep 101 on sleep behavior and sleep hygiene in completers, we conducted a series of repeated-measure tests, including the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks tests to compare T0 and T1 sleep behavior outcomes and the Stuart-Maxwell Marginal Homogeneity Test to evaluate differences between T0 and T1 SHI item responses. For all analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and Cohen’s d was used to calculate and interpret effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Three hundred thirty-eight college students initially consented to participate in Sleep 101 and completed the baseline survey (T

0). Post-intervention (T

1) assessment was completed by 25 participants, on average 51.6 (range 23-71) days after taking part in T

0. Most of the sample (96.4%) reported not receiving sleep education before participating in Sleep 101.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics regarding demographics, sleep behavior and sleep hygiene practices.

As shown in

Table 1, the age distribution for non-completers was younger (48.9% ≤ 18 years) in comparison to completers (36.0% ≤ 18 years,

p = 0.015). In addition, non-completers were more likely to be in their first year of college (67.7%) versus completers (44.0%,

p = 0.002) and thus less academically advanced.

Completers: Baseline (T0) and Post-Intervention (T1) Results

For completers (N= 25), there were significant T0 vs. T1 differences in weekday sleep duration (p = .031) with a large effect size of d = .954. After participating in Sleep 101, 40.0% of the completers reported that their sleep quality increased “a little” or “a great deal”.

Regarding behavior changes, 41.7% (“agree” and “strongly agree”) of the students indicated pulling fewer all-nighters after completing Sleep 101. Additionally, more than half of the participants (62.5%) (“agree” and “strongly agree”) started to make it a priority not to drive drowsy or when feeling sleepy. 33.4% (“agree” and “strongly agree”) began to make changes to their daily routines or environment to improve their sleep, and the majority (54.1%) were confident in maintaining these changes to improve their sleep in the next two months.

The global SHI (median (IQR)) in completers showed a slight, although non-significant improvement from baseline 24.00 (21.00, 27.00) to post-intervention 23.00 (19.00, 26.50) assessment. Stuart-Maxwell Marginal Homogeneity Test revealed statistically significant T0 and T1 differences (p = .028, d = 0.980) for one item, indicating that completers were less likely to engage in prior bedtime activities such as using electronic devices or doing housekeeping.

Discussion

This study explored the effects of a sleep education program (Sleep 101) on college students’ sleep behavior and sleep hygiene. First, the proportion of college students who received sleep education before participating in Sleep 101 was smaller in our sample (3.6%) compared to an earlier study (Semsarian et al., 2021), where one-third of students already had prior knowledge. Although the majority of our sample was satisfied with their sleep quality, 37.9% of participants indicated poor sleep quality, which again supports literature (Brown et al., 2002) highlighting the importance of sleep promotion and emphasizing the need for educational programs to improve students’ sleep.

Regarding changes in sleep behavior, we observed a significant increase in weekday sleep duration among Sleep 101 participants who completed the baseline and post-intervention assessment. This finding is in contradistinction to other studies (Kloss et al., 2016; Semsarian et al., 2021) that did not find changes in sleep behavior. However, our findings are similar to those from Levenson et al. (2016) that demonstrated improvements in sleep patterns, including increased sleep duration, decreased sleep onset latency and greater sleep efficacy. Unlike previous studies (Baroni et al., 2018; Kloss et al., 2016), we did not find changes in the overall sleep hygiene that were of statistical relevance, but our results indicate a trend towards more favorable sleep hygiene practices among those who experienced Sleep 101, suggesting that participating in a sleep education program might have beneficial effects on students’ sleep habits. Furthermore, we found changes in one specific item of the SHI suggesting that students were significantly less likely to engage in prior bedtime activities (e.g., playing video games, using the internet, or cleaning) after participating in Sleep 101 compared to baseline assessment.

The study’s findings should be interpreted within the context of study limitations. Firstly, the number of students who completed the post-study questionnaires was particularly low (7.4%). In addition, demographic composition of the study sample was somewhat restricted, originating solely from one college institution and predominantly comprising female participants. This limited scope could affect the broader applicability of the results to more diverse populations. Moreover, the study encountered challenges associated with a low response rate from students who completed both assessments. This could introduce potential biases and further hinder the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the effectiveness of Sleep 101 may have been influenced by the characteristics of the sample population. It’s plausible that students who voluntarily enrolled in the course already demonstrated heightened levels of health-seeking behaviors compared to the broader student population, thus potentially limiting the observed outcomes due to self-selection bias. Furthermore, the study’s design, relying solely on a pre-post study design without a control group, poses limitations. The absence of objective sleep data to track changes in sleep behavior also hinders the ability to solely attribute observed changes to participation in the online sleep education program. These methodological constraints underscore the need for cautious interpretation of the study results.

Conclusion

Given the prevalence of problematic sleep among college students, there is a pressing need for interventions such Sleep 101 to address this public health issue. Despite the limitations mentioned above, the findings of our study are encouraging and suggest that a brief online sleep education program has the potential to improve sleep behavior and sleep habits among college students. Moreover, implementing such a sleep education program could offer a cost-effective and readily scalable approach that may improve sleep patterns and serve as a preventive measure for addressing sleep-related issues among college students. Future studies could derive valuable insights by implementing a sleep education program over an extended duration, perhaps spanning one or two semesters, as opposed to the shorter timeframe observed in previous research. Additionally, incorporating follow-up assessments would allow for identifying any long-term effects of the intervention.

Funding Statement

“Sleep 101” was developed as a collaboration between the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders and Start School Later/Healthy Hours. Funding was provided by the Snider Family Fund.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank Diana Walker Moyer, Director of Health Services at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, for supporting the recruitment process for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Robbins reports consulting fees from Sonesta Hotels international, byNacht GmbH, Oura Ring, One Care Media. Dr. Quan reports consulting fees from Teledoc, Whispersom, and Apnimed and honoraria from Frontiers in Sleep. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Baroni, A., Bruzzese, J. M., Di Bartolo, C. A., Ciarleglio, A., & Shatkin, J. P. (2018). Impact of a sleep course on sleep, mood and anxiety symptoms in college students: A pilot study. J Coll Health, 66(1), 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. P., Jarrett, M. A., Luebbe, A. M., Garner, A. A., Burns, G. L., & Kofler, M. J. (2018). Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health, 4(2), 174-181. [CrossRef]

- Brown, F. Brown, F., Buboltz, W., & Jr, W. C. (2002). Applying sleep research to university students: Recommendations for developing a student sleep education program. Journal of College Student Development, 43, 411-416.

- Carpi, M., Cianfarani, C., & Vestri, A. (2022). Sleep Quality and Its Associations with Physical and Mental Health-Related Quality of Life among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(5). [CrossRef]

- Cellini, N., Menghini, L., Mercurio, M., Vanzetti, V., Bergo, D., & Sarlo, M. (2020). Sleep quality and quantity in Italian University students: an actigraphic study. Chronobiol Int, 37(11), 1538-1551. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Dietrich, S. K., Francis-Jimenez, C. M., Knibbs, M. D., Umali, I. L., & Truglio-Londrigan, M. (2016). Effectiveness of sleep education programs to improve sleep hygiene and/or sleep quality in college students: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep, 14(9), 108-134. [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, K., Melnyk, B. M., Tan, A., & Amaya, M. (2019). Heart checks in college-aged students link poor sleep to cardiovascular risk. Journal of American College Health, 67(2), 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Hershner, S. D., & Chervin, R. D. (2014). Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nature and science of sleep, 6, 73-84. [CrossRef]

- Kloss, J. D., Nash, C. O., Walsh, C. M., Culnan, E., Horsey, S., & Sexton-Radek, K. (2016). A “Sleep 101” Program for College Students Improves Sleep Hygiene Knowledge and Reduces Maladaptive Beliefs about Sleep. Behav Med, 42(1), 48-56. [CrossRef]

- Levenson, J. C., Miller, E., Hafer, B. L., Reidell, M. F., Buysse, D. J., & Franzen, P. L. (2016). Pilot study of a sleep health promotion program for college students. Sleep Health, 2(2), 167-174. 2. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D. C., Najafi, A., Afifi, L., Bassetti, C. L. A., Buysse, D. J., Han, F., Högl, B., Melaku, Y. A., Morin, C. M., Pack, A. I., Poyares, D., Somers, V. K., Eastwood, P. R., Zee, P. C., & Jackson, C. L. (2023). The need to promote sleep health in public health agendas across the globe. The Lancet Public Health, 8(10), e820-e826. 10. [CrossRef]

- Lund, H. G., Reider, B. D., Whiting, A. B., & Prichard, J. R. (2010). Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health, 46(2), 124-132. 2. [CrossRef]

- Mastin, D. F., Bryson, J., & Corwyn, R. (2006). Assessment of Sleep Hygiene Using the Sleep Hygiene Index. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 223-227. 29, 3, 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Okano, K., Kaczmarzyk, J. R., Dave, N., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Grossman, J. C. (2019). Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. npj Science of Learning, 4(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Quan, S. F., Anderson, J. L., & Hodge, G. K. (2013). Use of a supplementary internet based education program improves sleep literacy in college psychology students. J Clin Sleep Med, 9(2), 155-160. [CrossRef]

- Schlarb, A. A., Kulessa, D., & Gulewitsch, M. D. (2012). Sleep characteristics, sleep problems, and associations of self-efficacy among German university students. Nature and science of sleep, 4, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Schmickler, J. M., Blaschke, S., Robbins, R., & Mess, F. (2023). Determinants of Sleep Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study in University Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 20(3). [CrossRef]

-

The Science of Sleep and Dreams. Retrieved 12.02.2024 from https://online.stanford.edu/courses/csp-xsci-82-science-sleep-and-dreams.

- Semsarian, C. R., Rigney, G., Cistulli, P. A., & Bin, Y. S. (2021). Impact of an Online Sleep and Circadian Education Program on University Students’ Sleep Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(19). [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, B., Vedaa, Ø., Harvey, A. G., Glozier, N., Pallesen, S., Aarø, L. E., Lønning, K. J., & Hysing, M. (2019). Sleep patterns and insomnia in young adults: A national survey of Norwegian university students. Journal of Sleep Research, 28(2), e12790. [CrossRef]

-

Sleep (Gen Ed 1038). Retrieved 12.02.2024 from https://gened.fas.harvard.edu/classes/sleep.

- Toscano-Hermoso, M. D., Arbinaga, F., Fernández-Ozcorta, E. J., Gómez-Salgado, J., & Ruiz-Frutos, C. (2020). Influence of Sleeping Patterns in Health and Academic Performance among University Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(8). [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Bíró, É. (2021). Determinants of sleep quality in college students: A literature review. EXPLORE, 17(2), 170-177. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).