Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Exposure Variable

2.3. Outcome Variables

2.4. Covariables

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

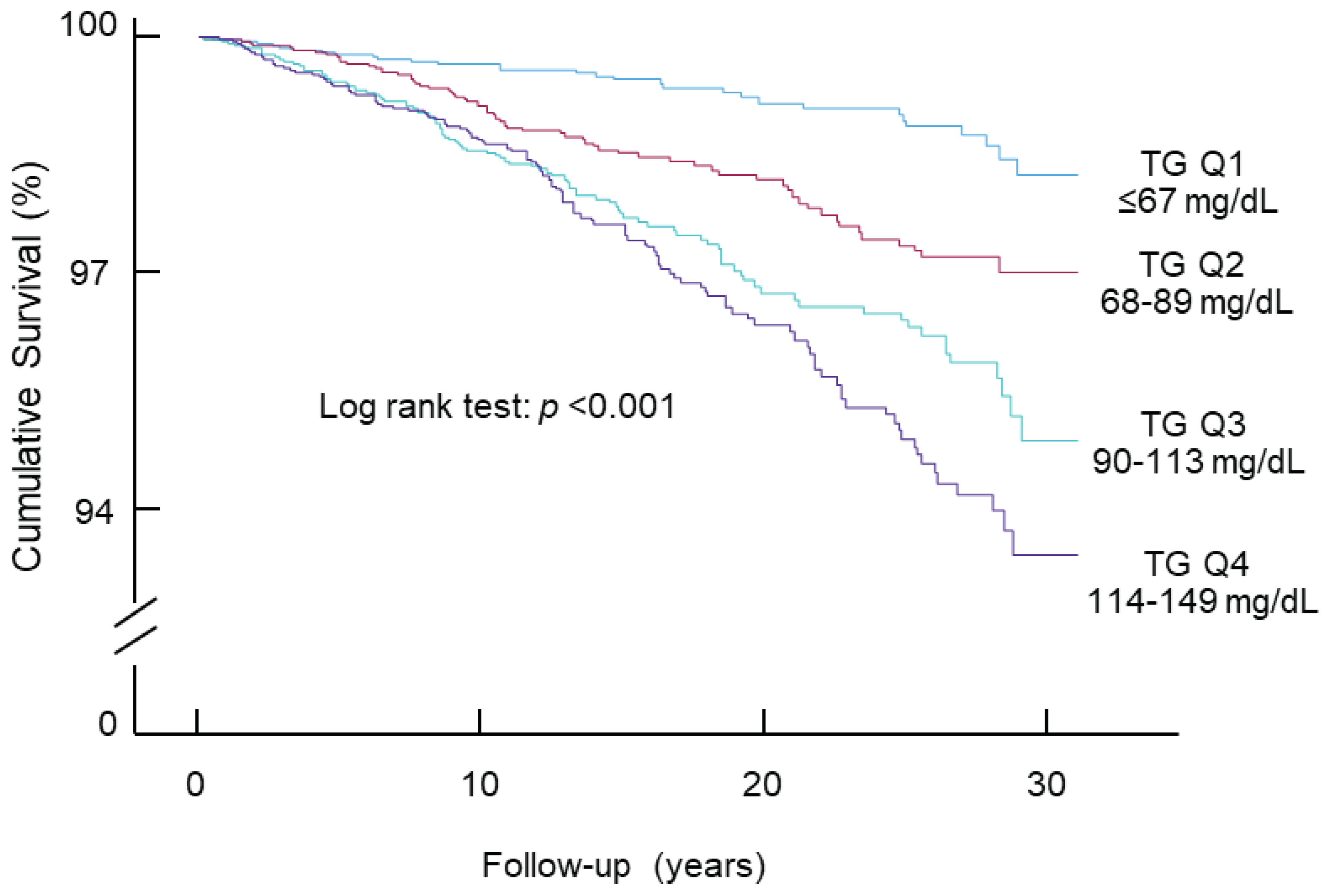

3.2. Association of Triglycerides within the Normal Range with Diabetes Mortality

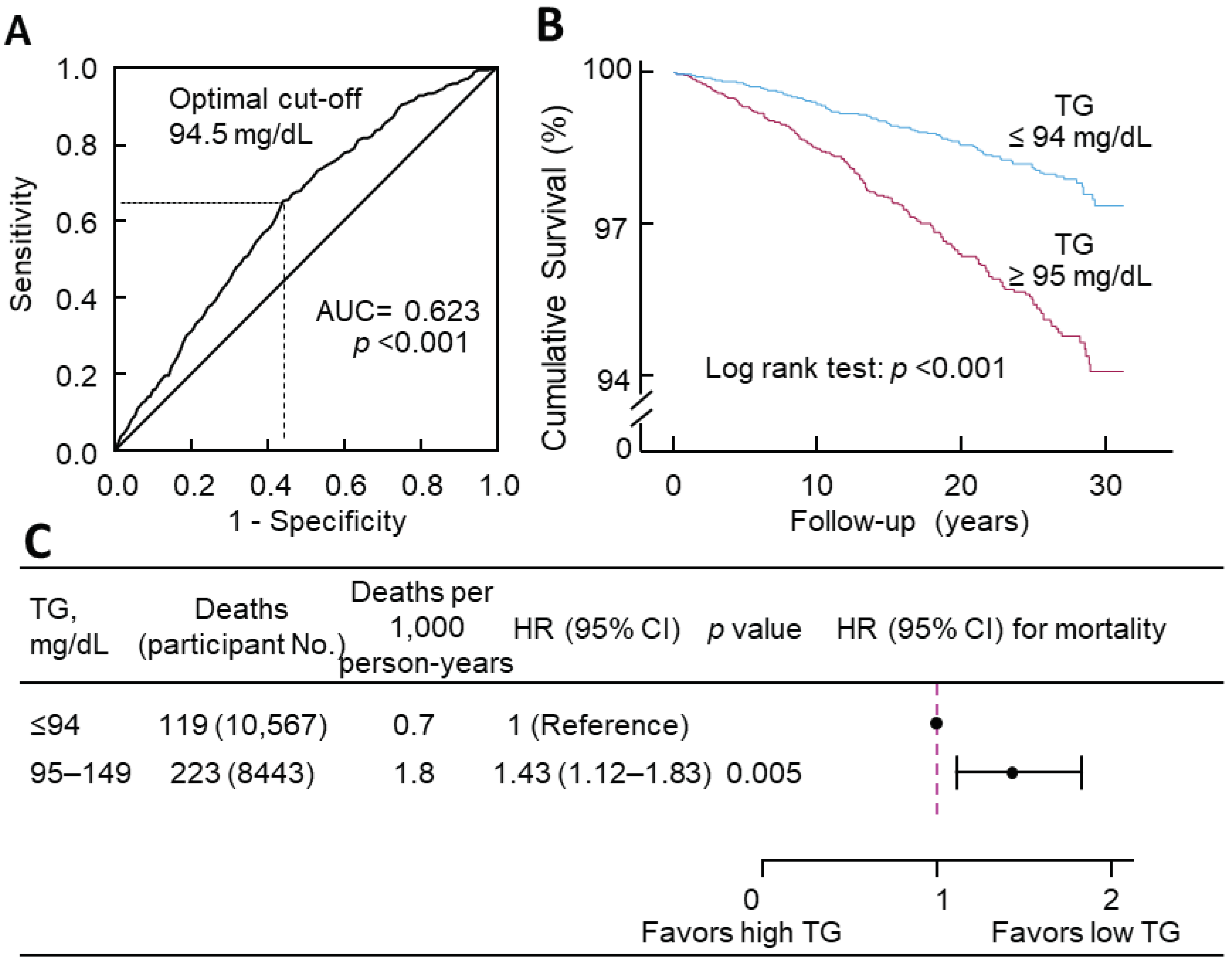

3.3. The Optimal Cutoff of Triglycerides for Diabetes Mortality

3.4. Association of Triglycerides with Hypertension Mortality, CVD Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Ren, Y.; Shan, P.-F. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: an analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, M.; Long, Z.; Ning, H.; Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, F.; Pan, A. Global burden of type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults, 1990-2019: systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 2022, 379, e072385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.B.; Hashim, M.J.; King, J.K.; Govender, R.D.; Mustafa, H.; Al Kaabi, J. Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes - Global Burden of Disease and Forecasted Trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2020, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, V. Management of hypertriglyceridemia. BMJ 2020, 371, m3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mawali, A.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Jayapal, S.K.; Morsi, M.; Pinto, A.D.; Al-Shekaili, W.; Al-Kharusi, H.; Al-Balushi, Z.; Idikula, J. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetes in a large community-based study in the Sultanate of Oman: STEPS survey 2017. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2021, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, I.; Martín-Nieto, A.; Martínez, R.; Casanovas-Marsal, J.O.; Aguayo, A.; Del Olmo, J.; Arana, E.; Fernandez-Rubio, E.; Castaño, L.; Gaztambide, S. Incidence of diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors in the adult population of the Basque country, Spain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.Y.; Huang, J.F.; Hsieh, M.Y.; Lee, L.P.; Hou, N.J.; Yu, M.L.; Chuang, W.L. Links between triglyceride levels, hepatitis C virus infection and diabetes. Gut 2007, 56, 1167–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Higher fasting triglyceride predicts higher risks of diabetes mortality in US adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Agostino, R.B., Jr.; Hamman, R.F.; Karter, A.J.; Mykkanen, L.; Wagenknecht, L.E.; Haffner, S.M. Cardiovascular disease risk factors predict the development of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2234–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, P.W.; Meigs, J.B.; Sullivan, L.; Fox, C.S.; Nathan, D.M.; D'Agostino, R.B., Sr. Prediction of incident diabetes mellitus in middle-aged adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujihara, K.; Sugawara, A.; Heianza, Y.; Sairenchi, T.; Irie, F.; Iso, H.; Doi, M.; Shimano, H.; Watanabe, H.; Sone, H.; et al. Utility of the triglyceride level for predicting incident diabetes mellitus according to the fasting status and body mass index category: the Ibaraki Prefectural Health Study. J Atheroscler Thromb 2014, 21, 1152–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimentidis, Y.C.; Chougule, A.; Arora, A.; Frazier-Wood, A.C.; Hsu, C.H. Triglyceride-Increasing Alleles Associated with Protection against Type-2 Diabetes. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirosh, A.; Shai, I.; Bitzur, R.; Kochba, I.; Tekes-Manova, D.; Israeli, E.; Shochat, T.; Rudich, A. Changes in triglyceride levels over time and risk of type 2 diabetes in young men. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2032–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshara, A.; Cohen, E.; Goldberg, E.; Lilos, P.; Garty, M.; Krause, I. Triglyceride levels and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal large study. J. Investig. Med. 2016, 64, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ma, S.; Qian, T.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.; Hou, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G.; Jelinic, M.; et al. Normal Triglycerides Are Positively Associated with Plasma Glucose and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in Chinese Adults. Preprints 2024, 2024011501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Yan, W.; Wang, A.; Wang, W.; Gao, Z.; Tang, X.; Yan, L.; Wan, Q.; et al. A high triglyceride glucose index is more closely associated with hypertension than lipid or glycemic parameters in elderly individuals: a cross-sectional survey from the Reaction Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Magliano, D.J.; Charchar, F.J.; Sobey, C.G.; Drummond, G.R.; Golledge, J. Fasting triglycerides are positively associated with cardiovascular mortality risk in people with diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadström, B.N.; Pedersen, K.M.; Wulff, A.B.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Elevated remnant cholesterol, plasma triglycerides, and cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1432–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindman, A.S.; Veierød, M.B.; Tverdal, A.; Pedersen, J.I.; Selmer, R. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular death in men and women from the Norwegian Counties Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, A.; Mitchell, P.; Rochtchina, E.; Wang, J.J. The association between circulating white blood cell count, triglyceride level and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: population-based cohort study. Atherosclerosis 2007, 192, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.Q.; Liu, X.C.; Lo, K.; Feng, Y.Q.; Zhang, B. A dose-independent association of triglyceride levels with all-cause mortality among adults population. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikhart, H.; Hubáček, J.A.; Peasey, A.; Kubínová, R.; Bobák, M. Association between fasting plasma triglycerides, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Czech population. Results from the HAPIEE study. Physiol. Res. 2015, 64, S355-361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipoprotein Analytical Laboratory. Total Cholesterol, HDL-Cholesterol, Triglycerides, and LDL-Cholesterol: Laboratory Procedure Manual. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/1999-2000/labmethods/lab13_met_lipids.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Witting, P.K.; Charchar, F.J.; Sobey, C.G.; Drummond, G.R.; Golledge, J. Dietary fatty acids and mortality risk from heart disease in US adults: an analysis based on NHANES. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Definition, prevalence, and risk factors of low sex hormone-binding globulin in US adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, e3946–e3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Late non-fasting plasma glucose predicts cardiovascular mortality independent of hemoglobin A1c. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungo, K.T.; Meier, R.; Valeri, F.; Schwab, N.; Schneider, C.; Reeve, E.; Spruit, M.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Rodondi, N.; Streit, S. Baseline characteristics and comparability of older multimorbid patients with polypharmacy and general practitioners participating in a randomized controlled primary care trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, T.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.; Hou, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G.; Drummond, G.R.; Sobey, C.G.; Charchar, F.J.; Golledge, J.; et al. Hyperuricemia is independently associated with hypertension in men under 60 years in a general Chinese population. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Stage 1 hypertension and risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in United States adults with or without diabetes. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Model. In Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis; Harrell, F.E., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2001; pp. 465–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azur, M.J.; Stuart, E.A.; Frangakis, C.; Leaf, P.J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, Y.; Noguchi, T.; Hayashi, T.; Tomiyama, N.; Ochi, A.; Hayashi, H. Eating alone and weight change in community-dwelling older adults during the coronavirus pandemic: A longitudinal study. Nutrition 2022, 102, 111697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.M. Best practice in statistics: The use of log transformation. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2022, 59, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Postabsorptive homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance is a reliable biomarker for cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality. Diabetes Epidemiology and Management 2021, 6, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, I. Defining an Optimal Cut-Point Value in ROC Analysis: An Alternative Approach. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2017, 2017, 3762651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, M.K.; Khanna, P.; Kishore, J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J Ayurveda Res 2010, 1, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qian, T.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.; Hou, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G.; Drummond, G.R.; Sobey, C.G.; et al. Reduced renal function may explain the higher prevalence of hyperuricemia in older people. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kametani, T.; Koshida, H.; Nagaoka, T.; Miyakoshi, H. Hypertriglyceridemia is an independent risk factor for development of impaired fasting glucose and diabetes mellitus: a 9-year longitudinal study in Japanese. Intern. Med. 2002, 41, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, G.I. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 106, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.B.; Storgaard, H.; Holst, J.J.; Dela, F.; Madsbad, S.; Vaag, A.A. Insulin secretion and cellular glucose metabolism after prolonged low-grade intralipid infusion in young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phielix, E.; Begovatz, P.; Gancheva, S.; Bierwagen, A.; Kornips, E.; Schaart, G.; Hesselink, M.K.C.; Schrauwen, P.; Roden, M. Athletes feature greater rates of muscle glucose transport and glycogen synthesis during lipid infusion. JCI insight 2019, 4, e127928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zeng, F.-F.; Liu, Z.-M.; Zhang, C.-X.; Ling, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-M. Effects of blood triglycerides on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 prospective studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2013, 12, 159–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S.; Pasea, L.; Soran, H.; Downie, P.; Jones, R.; Hingorani, A.D.; Neely, D.; Denaxas, S.; Hemingway, H. Elevated plasma triglyceride concentration and risk of adverse clinical outcomes in 1.5 million people: a CALIBER linked electronic health record study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempfner, R.; Erez, A.; Sagit, B.-Z.; Goldenberg, I.; Fisman, E.; Kopel, E.; Shlomo, N.; Israel, A.; Tenenbaum, A. Elevated Triglyceride Level Is Independently Associated With Increased All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Established Coronary Heart Disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2016, 9, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miselli, M.-A.; Nora, E.D.; Passaro, A.; Tomasi, F.; Zuliani, G. Plasma triglycerides predict ten-years all-cause mortality in outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal observational study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.; Varbo, A.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Low Nonfasting Triglycerides and Reduced All-Cause Mortality: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Clin. Chem. 2014, 60, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.S.; Hong, S.; Han, K.; Park, C.Y. Fenofibrate add-on to statin treatment is associated with low all-cause death and cardiovascular disease in the general population with high triglyceride levels. Metabolism 2022, 137, 155327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Y. Fasting status modifies the association between triglyceride and all-cause mortality: A cohort study. Health Sci Rep 2022, 5, e642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Sakata, S.; Arima, H.; Yamato, I.; Ibaraki, A.; Ohtsubo, T.; Matsumura, K.; Fukuhara, M.; Goto, K.; Kitazono, T. Relationship between casual serum triglyceride levels and the development of hypertension in Japanese. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Íñigo, L.; Navarro-González, D.; Pastrana-Delgado, J.; Fernández-Montero, A.; Martínez, J.A. Association of triglycerides and new lipid markers with the incidence of hypertension in a Spanish cohort. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Fan, F.; Jia, J.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, P.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, Y. Lipid profiles and the risk of new-onset hypertension in a Chinese community-based cohort. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2021, 31, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paynter, N.P.; Sesso, H.D.; Conen, D.; Otvos, J.D.; Mora, S. Lipoprotein subclass abnormalities and incident hypertension in initially healthy women. Clin. Chem. 2011, 57, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K. Triglyceride, an Independent Risk Factor for New-Onset Hypertension: A Perspective. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2023, 23, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szili-Torok, T.; Xu, Y.; de Borst, M.H.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Tietge, U.J.F. Normal Fasting Triglyceride Levels and Incident Hypertension in Community-Dwelling Individuals Without Metabolic Syndrome. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2023, 12, e028372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasai, T.; Miyauchi, K.; Yanagisawa, N.; Kajimoto, K.; Kubota, N.; Ogita, M.; Tsuboi, S.; Amano, A.; Daida, H. Mortality risk of triglyceride levels in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart 2013, 99, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, M.J.; van der Graaf, Y.; de Borst, G.J.; Kappelle, L.J.; Nathoe, H.M.; Visseren, F.L.J. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, Triglycerides, and Apolipoprotein B and Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Manifest Arterial Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 118, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.B.; Tong, P.C.; Chow, C.C.; So, W.Y.; Ng, M.C.; Ma, R.C.; Osaki, R.; Cockram, C.S.; Chan, J.C. Triglyceride predicts cardiovascular mortality and its relationship with glycaemia and obesity in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2005, 21, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, K.; Iso, H.; Sairenchi, T.; Irie, F.; Takizawa, N.; Koba, A.; Tomizawa, T.; Ota, H. Diabetes Mellitus Modifies the Association of Serum Triglycerides with Ischemic Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: The Ibaraki Prefectural Health Study (IPHS). J Atheroscler Thromb 2022, 29, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.Y.; Ye, X.F.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, C.S.; Huang, Q.F.; Wang, J.G. Serum triglycerides concentration in relation to total and cardiovascular mortality in an elderly Chinese population. J Geriatr Cardiol 2022, 19, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, P.P.; Philip, S.; Hull, M.; Granowitz, C. Association of Elevated Triglycerides With Increased Cardiovascular Risk and Direct Costs in Statin-Treated Patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1670–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, P.P.; Granowitz, C.; Hull, M.; Liassou, D.; Anderson, A.; Philip, S. High Triglycerides Are Associated With Increased Cardiovascular Events, Medical Costs, and Resource Use: A Real-World Administrative Claims Analysis of Statin-Treated Patients With High Residual Cardiovascular Risk. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2018, 7, e008740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Tu, Q.M.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.P.; Wang, N.S.; Jin, H.M. Triglyceride-lowering therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular events, stroke, and mortality in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2023, 117187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; Ferranti, S.d.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 139, e1082–e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, J.ø.; Hein, H.O.; Suadicani, P.; Gyntelberg, F. Triglyceride Concentration and Ischemic Heart Disease. Circulation 1998, 97, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikhonoff, V.; Casiglia, E.; Virdis, A.; Grassi, G.; Angeli, F.; Arca, M.; Barbagallo, C.M.; Bombelli, M.; Cappelli, F.; Cianci, R.; et al. Prognostic Value and Relative Cutoffs of Triglycerides Predicting Cardiovascular Outcome in a Large Regional-Based Italian Database. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2024, 13, e030319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, A.; Muntner, P.; Batuman, V.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Guallar, E. Blood lead below 0.48 micromol/L (10 microg/dL) and mortality among US adults. Circulation 2006, 114, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMahon, S.; Peto, R.; Cutler, J.; Collins, R.; Sorlie, P.; Neaton, J.; Abbott, R.; Godwin, J.; Dyer, A.; Stamler, J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990, 335, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Quartiles of triglycerides (range, mg/dL) | All | p | ||||

| Q1 (≤ 67) | Q2 (68–89) | Q3 (90–113) | Q4 (114–149) | |||

| Sample size | 4711 | 4798 | 4651 | 4850 | 19,010 | NA |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 41 (17) | 47 (19) | 49 (19) | 51 (19) | 47 (19) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 1995 (42) | 2178 (45) | 2225 (48) | 2369 (49) | 8767 (46) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 56 (47–62) | 79 (73–84) | 101 (95–107) | 129 (121–139) | 89 (68–114) | <0.001 |

| FPG, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 92 (87–99) | 95 (88–102) | 97 (90–105) | 99 (92–108) | 96 (89–104) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25 (22–28) | 26 (23–30) | 27 (24–31) | 28 (25–32) | 26 (23–30) | <0.001 |

| SBP, mm Hg, median (IQR) | 115 (106–126) | 118 (109–131) | 120 (111–133) | 123 (112–137) | 119 (109–132) | <0.001 |

| TC, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 173 (152–197) | 186 (164–212) | 194 (170–219) | 201 (177–229) | 188 (164–215) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 59 (50–71) | 55 (46–65) | 52 (44–62) | 48 (41–58) | 54 (45–64) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1774 (38) | 2027 (42) | 2071 (45) | 2307 (48) | 8179 (43) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1733 (37) | 1389 (29) | 1053 (23) | 821 (17) | 4996 (26) | |

| Hispanic | 927 (20) | 1132 (24) | 1271 (27) | 1478 (31) | 4808 (25) | |

| Other | 277 (6) | 250 (5) | 256 (6) | 244 (5) | 1027 (5) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||||

| < High School | 1133 (24) | 1391 (29) | 1497 (32) | 1662 (34) | 5683 (30) | <0.001 |

| High School | 1218 (26) | 1228 (26) | 1177 (25) | 1229 (25) | 4852 (26) | |

| > High School | 2353 (50) | 2153 (45) | 1964 (42) | 1945 (40) | 8415 (44) | |

| Unknown | 7 (0) | 26 (1) | 13 (0) | 14 (0) | 60 (0) | |

| Poverty-income ratio, n (%) | ||||||

| < 130% | 1281 (27) | 1359 (28) | 1314 (28) | 1370 (28) | 5324 (28) | 0.10 |

| 130%–349% | 1726 (37) | 1745 (36) | 1723 (37) | 1872 (39) | 7066 (37) | |

| ≥ 350% | 1315 (28) | 1290 (27) | 1218 (26) | 1248 (26) | 5071 (27) | |

| Unknown | 389 (8) | 404 (8) | 396 (9) | 360 (7) | 1549 (8) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | ||||||

| Active | 1494 (32) | 1382 (29) | 1220 (26) | 1162 (24) | 5258 (28) | <0.001 |

| Insufficiently active | 1741 (37) | 1758 (37) | 1724 (37) | 1855 (38) | 7078 (37) | |

| Inactive | 1475 (31) | 1657 (35) | 1703 (37) | 1831 (38) | 6666 (35) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 4 (0) | 2 (0) | 8 (0) | |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 drink/week | 722 (15) | 798 (17) | 815 (18) | 905 (19) | 3240 (17) | <0.001 |

| < 1 drink/week | 1092 (23) | 1073 (22) | 1051 (23) | 1100 (23) | 4316 (23) | |

| 1–6 drinks/week | 1135 (24) | 1032 (22) | 954 (21) | 906 (19) | 4027 (21) | |

| ≥ 7 drinks/week | 577 (12) | 617 (13) | 628 (14) | 599 (12) | 2421 (13) | |

| Unknown | 1185 (25) | 1278 (27) | 1203 (26) | 1340 (28) | 5006 (26) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Current smoker | 915 (19) | 1121 (23) | 1090 (23) | 1055 (22) | 4181 (22) | <0.001 |

| Past smoker | 904 (19) | 1053 (22) | 1140 (25) | 1307 (27) | 4404 (23) | |

| Non-smoker | 2890 (61) | 2620 (55) | 2417 (52) | 2485 (51) | 10,412 (55) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0) | 4 (0) | 4 (0) | 3 (0) | 13 (0) | |

| Family history of diabetes, n (%) | 0.35 | |||||

| Yes | 1930 (41) | 1964 (41) | 1968 (42) | 2087 (43) | 7949 (42) | |

| No | 2685 (57) | 2744 (57) | 2596 (56) | 2671 (55) | 10,696 (56) | |

| Unknown | 96 (2) | 90 (2) | 87 (2) | 92 (2) | 365 (2) | |

| Models | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Model 1 | 4.24 | 2.98–6.03 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 2.21 | 1.54–3.19 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.70 | 1.17–2.48 | <0.01 |

| Model 4 | 1.66 | 1.10–2.51 | 0.02 |

| Model 5 | 1.57 | 1.04–2.38 | 0.03 |

| Models | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||||

| HR | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Model 1 | 1 | 2.18 | 1.44–3.29 | <0.001 | 3.44 | 2.33–5.08 | <0.001 | 4.17 | 2.84–6.11 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.66 | 1.10–2.52 | 0.02 | 2.12 | 1.43–3.14 | <0.001 | 2.33 | 1.58–3.44 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1.46 | 0.97–2.22 | 0.07 | 1.81 | 1.22–2.70 | <0.01 | 1.84 | 1.24–2.73 | <0.01 |

| Model 4 | 1 | 1.44 | 0.94–2.20 | 0.09 | 1.81 | 1.20–2.74 | 0.01 | 1.80 | 1.18–2.75 | 0.01 |

| Model 5 | 1 | 1.42 | 0.93–2.16 | 0.11 | 1.77 | 1.17–2.67 | 0.01 | 1.72 | 1.12–2.63 | 0.01 |

| Models | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Model 1 | 4.41 | 3.05–6.37 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 2.25 | 1.54–3.30 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.71 | 1.16–2.53 | 0.01 |

| Model 4 | 1.63 | 1.06–2.51 | 0.03 |

| Model 5 | 1.55 | 1.01–2.39 | 0.046 |

| Models | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Model 1 | 4.41 | 3.07–6.35 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 2.32 | 1.59–3.39 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.76 | 1.19–2.60 | <0.01 |

| Model 4 | 1.64 | 1.07–2.52 | 0.02 |

| Model 5 | 1.56 | 1.02–2.40 | 0.04 |

| Models | Hypertension mortality | CVD mortality | All-cause mortality | ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Model 1 | 2.54 | 1.99–3.25 | <0.001 | 2.43 | 2.08–2.83 | <0.001 | 2.35 | 2.14–2.57 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.19 | 0.92–1.54 | 0.19 | 1.08 | 0.92–1.28 | 0.34 | 1.10 | 1.00–1.21 | 0.05 |

| Model 3 | 1.06 | 0.81–1.38 | 0.70 | 1.01 | 0.85–1.19 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 1.00–1.22 | 0.05 |

| Model 4 | 1.07 | 0.79–1.43 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 0.80–1.17 | 0.72 | 1.15 | 1.03–1.28 | 0.01 |

| Model 5 | 1.06 | 0.79–1.43 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.79–1.16 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 1.02–1.28 | 0.02 |

| Models | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||||

| HR | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Hypertension mortality | ||||||||||

|

Model 1 |

1 | 1.65 | 1.27–2.13 | <0.001 | 2.02 | 1.57–2.60 | <0.001 | 2.27 | 1.77–2.91 | <0.001 |

|

Model 2 |

1 | 1.18 | 0.91–1.53 | 0.23 | 1.14 | 0.89–1.48 | 0.30 | 1.16 | 0.9–1.49 | 0.25 |

|

Model 3 |

1 | 1.11 | 0.85–1.44 | 0.46 | 1.06 | 0.82–1.37 | 0.68 | 1.04 | 0.81–1.35 | 0.75 |

|

Model 4 |

1 | 1.11 | 0.85–1.45 | 0.46 | 1.05 | 0.80–1.38 | 0.74 | 1.04 | 0.79–1.39 | 0.77 |

|

Model 5 |

1 | 1.11 | 0.85–1.45 | 0.46 | 1.05 | 0.80–1.37 | 0.75 | 1.04 | 0.78–1.38 | 0.79 |

| CVD mortality | ||||||||||

|

Model 1 |

1 | 1.66 | 1.41–1.96 | <0.001 | 2.06 | 1.75–2.42 | <0.001 | 2.25 | 1.92–2.64 | <0.001 |

|

Model 2 |

1 | 1.16 | 0.98–1.37 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.96–1.32 | 0.16 | 1.11 | 0.94–1.30 | 0.22 |

|

Model 3 |

1 | 1.14 | 0.96–1.35 | 0.13 | 1.09 | 0.93–1.29 | 0.29 | 1.05 | 0.89–1.24 | 0.55 |

|

Model 4 |

1 | 1.12 | 0.95–1.33 | 0.19 | 1.07 | 0.90–1.27 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 0.85–1.22 | 0.88 |

|

Model 5 |

1 | 1.12 | 0.94–1.33 | 0.20 | 1.07 | 0.90–1.27 | 0.46 | 1.01 | 0.84–1.21 | 0.94 |

| All-cause mortality | ||||||||||

|

Model 1 |

1 | 1.59 | 1.44–1.75 | <0.001 | 1.86 | 1.70–2.05 | <0.001 | 2.16 | 1.98–2.37 | <0.001 |

|

Model 2 |

1 | 1.13 | 1.03–1.25 | 0.01 | 1.06 | 0.97–1.17 | 0.23 | 1.10 | 1.00–1.21 | 0.04 |

|

Model 3 |

1 | 1.14 | 1.04–1.26 | 0.01 | 1.07 | 0.98–1.18 | 0.15 | 1.11 | 1.01–1.22 | 0.03 |

|

Model 4 |

1 | 1.16 | 1.05–1.28 | <0.01 | 1.10 | 1.00–1.22 | 0.06 | 1.15 | 1.03–1.27 | 0.01 |

|

Model 5 |

1 | 1.15 | 1.05–1.27 | <0.01 | 1.10 | 0.99–1.21 | 0.07 | 1.14 | 1.03–1.27 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).