1. Introduction

Nowadays, corporate sustainability is becoming a key factor for success and long-term viability, as interest in environmental, social, and economic responsibility is constantly increasing. According to Çera et al. [

1] and Betakova et al. [

2], companies that are aware of their impact on society and the environment become leaders in the field of responsible business and contribute to the creation of a better future. Sustainability focuses on meeting current needs without jeopardizing the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [

3]. The main goal of sustainability is to minimize negative impacts on the environment, preserve natural resources, and promote a balance between economic development, social well-being, and environmental responsibility. According to Schaltegger et al. [

4], sustainability is often perceived as an integral part of various policies, strategies, and business models in order to achieve long-term sustainable development of society. As a synonym for the concept of sustainability, the concept of ESG, which was created on the basis of the theory of Corporate Social Responsibility, is coming to the fore. The concept of ESG was created thanks to investors who demand the evaluation of the responsible behavior of companies and the prediction of possible future financial results also based on non-financial information [

5]. The activities carried out by companies in the field of ESG are not only intended to contribute to the mitigation of climate change by directing the European Union on the path of green transformation with the ultimate goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 but also to support the transformation to a fair and prosperous society with a modern and competitive economy [

6]. The European Commission has approved the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), aimed at reporting sustainability information in the form of a sustainability report (ESG report). The sustainability report will have to be compiled in accordance with the newly adopted European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) [

7].

In all areas of SME business, the importance of sustainability is growing, especially the effects on the area of finance [

8]. According to Nwachukwu et al. [

9], SME owners therefore need to adapt their understanding of their function, capabilities, and portfolio of services in the financial area so that they correspond to new requirements. The financial area is a central factor of motivation, which ensures the successful transformation of the organization into a sustainable enterprise [

10]. The degree of impact on the environment and society is important for maintaining the competitiveness of businesses. Not only in product development, logistics, or marketing, but also in the financial field, huge opportunities arise thanks to the focus on sustainability [

11,

12]. However, their use requires a change in business as well as in individual functions. Company management should therefore emphasize the sustainable future of their business [

13]. To realize this sustainable future, organizations should consider environmental, economic, social aspects, and their impact factors when making decisions and planning strategies.

The originality of this case study lies in the authors' examination of subjective perceptions of important factors of sustainability in the segment of small and medium-sized enterprises, comparing countries within the Visegrad group.

The structure of the scientific article is as follows.

The motivation and originality of the article are presented in the introduction section. The theoretical background of the article includes significant scientific findings on the selected factors of sustainability and financial performance within the scope of the article's topic. The subsequent section outlines the aim and methodology of data collection, formulation of statistical hypotheses, basic information on the questionnaire and factors, statistical methods, and the structure of respondents. The empirical results present an evaluation of the statistical hypotheses using pivot tables and statistical testing. The discussion section entails research findings and a comparison with international case studies. Finally, the conclusion addresses the limitations and suggests future research activities for the authors.

1. Theoretical Background

There is no single definition for the term 'sustainability' (sustainable development), as it can be defined in many ways. The OECD perceives sustainable development as a dynamic balance between economic, social, and environmental aspects of development in the conditions of globalization [

3]. According to Khan et al. [

14], sustainable development is a complex set of strategies that allow the use of economic means and technologies to satisfy human needs—material, cultural, and spiritual—while fully respecting environmental limits. For this to be possible on a global scale in today's world, it is necessary to redefine socio-political institutions and processes at the local, regional, and global levels. Sustainability is focused on three main areas: environmental, social, and economic. Currently, the concept of ESG is coming to the fore, which assesses environmental, social, and governance activities [

7].

Corporate Social Responsibility can be defined as an approach to ethics, which is based on the responsible approach of the stakeholders themselves, affecting the operation of the company and reflecting the overall relationship of the company with its stakeholders [

1]. According to Betakova et al. [

2], businesses commit to conducting their operations in ways that protect the interests of current and future generations and strive to eliminate or minimize any harmful effects while maximizing their sustainable beneficial impact on society. In the European Union, socially responsible business is understood and assessed as part of the country's competitive performance [

15]. The evaluation and international comparison of socially responsible business among countries highlight the connection between economic performance and the achieved level of responsible business [

16].

Increasing demands for sustainability lead to a change in the thinking of SME owners in the financial area [

17]. As a result of a German study carried out in medium-sized enterprises, factors were identified that influence measures for the transformation of sustainable enterprises [

7,

18] - 1. A successful transformation towards sustainability requires the adaptation of current structures and processes of taxation and reporting. Sustainability cannot be developed independently of the financial field. 2. Support for the integration of the aspect of sustainability into the data and system environment: Sustainability requires a new form of data transparency, in which non-financial indicators are used to a significant extent. 3. Targeted adaptation of employee motivation: Successfully implemented transformations require highly motivated top management and employees. 4. Development of relevant knowledge on the subject of sustainability: Financial directors must find new ways of acting and can no longer concentrate on, or be limited to, financial indicators only. New kinds of knowledge are needed.

From the above, it follows that responsibility for the performance of SMEs in relation to strategic goals, including sustainable performance, requires the need to understand the relationships between the company's activities and their impact on financial as well as non-financial performance. According to Małkowska et al. [

19], evaluating and measuring SME performance is usually a feature of most thriving businesses. Key performance indicators help companies achieve sustainability and also ensure their environmental, economic, social, and Corporate Governance impacts. According to the results of several studies, e.g., Kocmanová et al. [

20], Tur-Porcar et al. [

21], Pavláková Dočekalová, Kocmanová [

22], Ahmad et al. [

7], the following indicators can be declared: Economic performance indicators: performance indicators (return on equity, sales, assets, and invested capital), economic results (profit, turnover, added value, market share), financial indicators (total liquidity, indebtedness, asset turnover), operating cash flow. Environmental performance indicators: investments (investments in natural resource protection, costs of investments in natural resources), emissions (total air emissions, total greenhouse gas emissions), resource consumption (total annual consumption, renewable energies, materials consumed, recycled input materials, total annual water consumption), waste (total annual waste production, total annual hazardous waste production). Social performance indicators: society (community contributions to municipalities), human rights (discrimination, equal opportunities), labor legal relations (employee turnover rate, education and training expenses, occupational diseases, number of workplace deaths), product liability (marketing communication, labeling of services and products). Corporate Governance performance indicators: monitoring and reporting (reporting on company goals, financial results, etc.), CG effectiveness (CG responsibility, ethical behavior), CG structure (CG remuneration, composition of CG members, equal opportunities), compliance (corruption, compliance with legal standards).

In addition to prerequisites such as orientation to economic, environmental, and social areas, development of quality of life, systematic long-term management, integration into the culture of the organization, and a broad-spectrum approach to stakeholders, risk management can also be implemented within the framework of a proactive approach [

23]. Risk management is a prerequisite for increasing the success of the business activities implemented by the organization from the perspective of sustainable development [

24]. Based on these facts, not only is socially responsible business coming to the fore, but also the growing need and importance of risk management within the company, especially due to rapid changes in the global business environment, which directly affect the success and sustainability of businesses. Through risk management, businesses can avoid costly lawsuits, damage to their reputation, and more [

25]. Risk management in the company is an important element of effective strategic management, which, through its activities, aims to reduce the negative impacts of various types of risks, i.e., especially market, financial, operational, personnel, and legislative, on planned goals.

Market risk is most often defined as the negative influence of the external environment, which is frequently associated with the failure of products and services in the markets [

26]. Market risk primarily assesses the impact of competition, customer behavior, suppliers, market development, etc., on the achievement of set goals. Market risk is considered the most serious risk perceived by SMEs in the V4 countries [

27]. Lopez-Torres et al. [

28] assess the impact of market risk on the sustainability and competitiveness of SMEs. Hernandez-Diaz et al. [

29] and Gorondutse et al. [

30] assessed the impacts of sustainability support on SME performance from the perspective of strategic flexibility. Bratianu et al. [

31] focused on assessing the impact of risk management on the sustainability of SMEs.

Financial risk is defined by Belas et al. [

32] as a potential loss incurred in the financial market, including losses caused by fluctuations in interest rates or non-payment of financial obligations. According to Civelek et al. [

33], financial risk arises from changes in the financial market as well as from the approach of managers to make informed decisions on financial risk management using individual financial instruments. Arsic et al. [

34] in their study assessed the impact of logistics capacities on the economic and financial sustainability of SMEs. Heenkend et al. [

35] and Kliuchnikava et al. [

36] evaluated the role of innovative capability in enhancing sustainability in SMEs as a perspective of the developing economy in Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Logan et al. [

37] processed results oriented towards the analysis of risks from the viewpoint of consequences for resilience, sustainability, and business management.

Operational risk, as defined by Lopez [

38], is the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems, or from external events. According to Agarwal and Ansell [

39], operational risks include product risks, process or system failures, legality and compliance issues, illegal or criminal activities, and human factors. Dumitrescu and Deselnicu [

40], along with Makovická Osvaldová et al. [

41] and Vandličková et al. [

42], identify operational risks primarily as failures in production processes, systems, and services, i.e., risks resulting from business interruptions. These risks are assessments of factors affecting the production-technological process, technical failures, accidents, insufficient utilization of production capacities, low innovation rates, obsolete production equipment, product failure, as well as external risk sources, e.g., loss of suppliers, and scarcity of resources and raw materials.

Personnel risk, according to Grabara et al. [

43], is defined as the risk of violating individual rights and freedoms, physical and psychological violence at work, humiliation of honor and dignity, health risks, job loss, and risks of reduced income. According to Strielkowski et al. [

44], personnel risk is perceived as a negative event with consequences affecting employee turnover, insufficient qualification of employees, employee mistakes, work morale, and relationships at the workplace. The human factor introduces a significant degree of unpredictability and uncertainty to any company activity, which can also lead to crisis situations, as noted by Fraser and Simkins [

45]. Gede Riana et al. [

46] argue that the quality of human capital in SMEs is fundamental to enhancing company performance. Boeske and Murray [

47] discuss sustainability leadership issues in SMEs. Belas et al. [

48] examine the effects of ethical and CSR factors on engineers' attitudes towards SME sustainability. Mizickova et al. [

49] present results focused on assessing the impact of knowledge risk management on enterprise sustainability.

National support and legislative changes are associated with the regulation of business, according to Slusarczyk and Grondys [

50]. This primarily concerns the effects of new laws and changes to existing laws and standards, as well as the consequences resulting from them. According to Virglerova et al. [

51], legislative risk represents the potential that government regulations or legislation may significantly change the business prospects of one or more companies. These changes may adversely affect investment interests in these companies. Legislative risk can occur as a direct result of government action or changes in the demand patterns of a company's customers. Several authors, including Kotasova et al. [

52] and Pop et al. [

53], note that the business environment in the V4 countries is regulated by a large number of legal regulations that are constantly subject to changes. Based on the studies processed by Virglerova et al. [

51], Musa et al. [

54], and Gorzeń-Mitka [

55], one of the biggest obstacles in SME business is the instability and ambiguity of laws. These frequent changes in laws make the legislative framework in the V4 countries opaque and complex for entrepreneurs.

Socially responsible business and risk management as a tool for the preventive prevention of

crisis situations have an irreplaceable place in today's society (e.g. Semenikhina et al. [

56], Long et al. [

57], Oliinyk et al. [

58]). According to Hudáková et al. [

59] on the one hand, risk management enables business activities to be carried out responsibly towards interested parties, because the company is also prepared for negative environmental developments. On the other hand, socially responsible business enables more effective risk assessment and management, because by following its principles, the company avoids many crisis situations. According to Dvorský et al. [

60] a crisis situation in an enterprise defines a limited course of events, which after the equilibrium state of enterprise systems and processes can be disturbed by its negative effects and scope, can seriously disrupt the functionality of operational processes, or of the entire enterprise. The cause of the increase in crisis situations of the company is a whole series of factors, which are both economic and psychological and have a direct connection with the management of Kubas et al. [

61] Truly anticipatory management thinks of potential crises long before they might occur through risk management.

2. Aim, Methodology, Variables, and Methods

Aim of the article is verify of differences in the perception on the selected factors of sustainability in the SMEs segment between countries in the middle Europe.

2.1. Data Collection

The research was conducted in four Central European countries: Hungary (HU), Poland (PL), the Slovak Republic (SR), and the Czech Republic (CR). The survey was completed by 1,090 owners or top managers of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs – with fewer than 250 employees; respondents). The distribution of respondents according to their country of business operation was as follows: 301 (27.6%) from PL, 362 (33.2%) from CR, 162 (14.9%) from SR, and 265 (24.3%) from HU. Data collection took place from December 2022 to January 2023 with the assistance of the external research agency MNFORCE. The selection of respondents was facilitated by the CAWI method (Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing).

The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part gathered demographic characteristics of the enterprise, such as the size of the enterprise, type of entity, number of years the enterprise has been in operation, level of internationalization, locality of business operation, and business sector. The second part focused on factors related to sustainability, including corporate social responsibility, crisis events in business, reputation and social media, market, financial, operational risk, personnel risk, national support and legislative changes, and sustainability itself. The questionnaire was translated into the national languages of the respondents to ensure a better understanding of the statements. Respondents were asked to express their attitude using one of the following types of answers (according to the Likert scale): A1 – strongly agree, A2 – agree,

…

, A4 – disagree, A5 – strongly disagree. The reliability and validity results confirmed that the questions in the questionnaire were well-formulated. Item-to-total correlation between items and factors confirmed a good connection. These indicators of questionnaire quality were validated.

2.1. Variables

The questionnaire contains the following business risk statements:

Reputation of SMEs in social media (RSM): RSM1: The company’s reputation has a significant role in our business. RSM2: Social media supports the growth of our company's performance. RSM3: Social media helps our business quickly share information with customers and partners. RSM4: Social networks have important role in our business.

Market risks (MR): MR1: I rate the market risk (lack of sales for my company) as acceptable. MR2: The stagnation of the market has no important impact on our business. MR3: Strong competition in the sector of business has no significant effect on our business. MR4: The level of consumers´ purchase has a positive influence on our business.

Personnel risk (PER): PER1: Our employees are the most important organisation assets. PER2: Our company heavily invests in improving the qualifications of our employees. PER3: Employee turnover has no negative impact on my business. PER4: Employee error has no effect on my (our) business.

National support and legislative changes (NSLCH): NSLCH1: In the last five years, conditions for doing business in my country have improved. NSLCH2: Institutions in the support of the business environment of our country help SME segment during crisis events (e.g. COVID-19; Russia-Ukraine conflict). NSLCH3: Business is affected by frequent legislative changes, but it has no negative impact on our (my) business. NSLCH4: I do not consider the business environment to be 'over-regulated'.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): CSR1: The concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) plays an important role in our company. CSR2: The implementation of the CSR concept has a positive effect on the future of SMEs. CSR3: CSR helps us to gain new business partners. CSR4: CSR has a positive impact on a firm’s financial performance.

Operational risks (OR): OR1: Our company has a sufficient utilisation of the production capacities. OR2: The company suppliers’ prices for products and services are adequate. OR3: Our company has no problem with distribution of our products/services. OR4: Our company has no problem with the suppliers (e.g. cooperation, numbers of suppliers, relationships).

Financial risk (FR): FR1: Our company has s sufficient profit. FR2: The indebtedness of the company is adequate (not a high share of debt). FR3: I can adequately manage financial risks in our company.FR4: Our company has no problem with an ability to pay obligations (insolvency).

Sustainability (S): S1: I understand the concept of sustainable business growth. S2: It is essential to perceive also the social and environmental impact of entrepreneurship. S3: The sustainable development of our company is a key aspect of entrepreneurship. S4: I perceive our company as sustainable.

Crisis events in business (CEB): CEB1: Crisis phenomena (COVID-19 pandemic, Russian-Ukrainian conflict and its impacts) have changed my view on the company’s sustainability. CEB2: The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the company's management. CEB3: The Russian-Ukrainian conflict has no negative impact on the functioning of our company on the market. CEB4: The Russian-Ukrainian conflict has no negative impact on the organization of the activities in our company. CEB5: Currently, uncertainty is not the main problem in SMEs.

2.1. Statistical Hypotheses and Methods

The following hypotheses were formulated:

H: The country of business operation is a statistical significant factor that affects the perception of reputation and social media (H_RSM), market risk (H_MR), personnel risk (H_PER), national support and legislative changes (H_NSLCH), corporate social responsibility (H_CSR), operational risk (H_OR), financial risk (H_FR), sustainability (H_S), and crisis events in business (H_CEB) in the segment of SMEs in the V4 countries.

The statistical hypotheses were verified using statistical methods and the IBM SPSS Statistics software. The analyses included sorting by one statistical sign (e.g., type of answer to the statement, such as RSM1,

…); sorting by two statistical signs (type of answer to the statement and country of business operation - CR, PL, SR, HU); calculation of absolute and relative frequencies of statistical signs; creation of pivot tables and aggregated indexes; and the application of the Z-score for comparing two population proportions, as presented in the tables (see

Table 1, …,

Table 4).

2.1. Structure of Respondents

Structure of respondents according to the country of doing of business.

Czech Republic (CR; n = 362). Size of enterprise: 222 (61.3%) - Microenterprises (less than or equal to nine employees), 84 (23.2%) - Small enterprise (between ten to 49 employees), 56 (15.5%) - Medium enterprise (between 50 to 249 employees); type of entity: 143 (39.5%) - Sole trader, 183 (50.6%) - Limited liability company, 36 (9.3%) - Joint-stock company; Business sector: 72 (19.9%) - Manufacturing, 76 (21.0%) - Retailing, 44 (12.2%) - Construction, 134 (37.0%) - Services, 36 (9.9%) - Another area; Number of years of enterprise: 64 (17.7%) - less than or equal to 3 years, 38 (10.5%) - more than 3 and less than or equal to 5 years, 75 (20.7%) - more than 5 and less than or equal to 10 years, 185 (51.1%) - more than 10 years; level of internationalization: 329 (90.9%) - domestic market (national business environment), 33 (9.1%) - foreign market (international business environment); locality of doing business: 155 (42.8%) - capital, 207 (57.2%) - others city.

Poland (PL; n = 301). Size of enterprise: 202 (67.1%) - Microenterprises (less than or equal to nine employees), 69 (22.9%) - Small enterprise (between ten to 49 employees), 30 (10.0%) - Medium enterprise (between 50 to 249 employees); type of entity: 203 (67.4%) - Sole trader, 81 (26.9%) - Limited liability company, 11 (3.7%) - Joint-stock company, 6 (2.0%) other type; Business sector: 28 (9.3%) - Manufacturing, 49 (16.3%) - Retailing, 52 (17.3%) - Construction, 101 (33.5%) - Services, 71 (23.6%) - Another area; Number of years of enterprise: 62 (20.6%) - less than or equal to 3 years, 99 (32.9%) - more than 3 and less than or equal to 5 years, 64 (21.3%) - more than 5 and less than or equal to 10 years, 76 (25.2%) - more than 10 years; level of internationalization: 266 (88.4%) - domestic market (national business environment), 35 (11.6%) - foreign market (international business environment); locality of doing business: 85 (28.2%) - capital, 216 (71.8%) - others city.

Hungary (HU; n = 265). Size of enterprise: 159 (60.0%) - Microenterprises (less than or equal to nine employees), 84 (31.7%) - Small enterprise (between ten to 49 employees), 22 (8.7%) - Medium enterprise (between 50 to 249 employees); Type of entity: 145 (54.7%) - Sole trader, 89 (33.6%) - Limited liability company, 18 (6.8%) - Joint-stock company, 13 (4.9%) other type; Business sector: 36 (13.6%) - Manufacturing, 71 (26.8%) - Retailing, 23 (8.7%) - Construction, 64 (24.2%) - Services, 71 (26.8%) - Another area; Number of years of enterprise: 73 (27.6%) - less than or equal to 3 years, 92 (34.7%) - more than 3 and less than or equal to 5 years, 49 (18.5%) - more than 5 and less than or equal to 10 years, 51 (19.2%) - more than 10 years; level of internationalization: 236 (89.1%) - domestic market (national business environment), 29 (10.9%) - foreign market (international business environment); locality of doing business: 132 (49.8%) - capital, 133 (50.2%) - others city.

Slovak Republic (SR; n = 162). Size of enterprise: 121 (74.7%) - Microenterprises (less than or equal to nine employees), 27 (16.7%) - Small enterprise (between ten to 49 employees), 14 (8.6%) - Medium enterprise (between 50 to 249 employees); Type of entity: 98 (60.5%) - Sole trader, 52 (32.1%) - Limited liability company, 12 (7.4%) - Joint-stock company; Business sector: 15 (9.3%) - Manufacturing, 39 (24.1%) - Retailing, 20 (12.4%) - Construction, 68 (42.0%) - Services, 20 (8.1%) - Another area; Number of years of enterprise: 40 (24.7%) - less than or equal to 3 years, 34 (21.0%) - more than 3 and less than or equal to 5 years, 35 (21.6%) - more than 5 and less than or equal to 10 years, 53 (32.7%) - more than 10 years; level of internationalization: 152 (93.8%) - domestic market (national business environment), 10 (6.2%) - foreign market (international business environment); locality of doing business: 55 (34.0%) - capital, 107 (66.0%) - others city.

3. Empirical Results from V4 Countries

Structure of answer in V4 countries (n = 1,090): RSM1: A1 = 578 (53.0%), A2 = 378 (34.7%), A3-A5 = 134 (12.3%); RSM2: A1 = 285 (26.1%), A2 = 409 (37.5%), A3-A5 = 396 (36.3%); RSM3: A1 = 330 (30.3%), A2 = 402 (36.9%), A3-A5 = 358 (32.8%); RMS4: A1 = 309 (28.3%), A2 = 348 (31.9%), A3-A5 = 433 (39.8%); MR1: A1 = 219 (20.1%), A2 = 466 (42.8%), A3-A5 = 405 (37.2%); MR2: A1 = 170 (15.6%), A2 = 298 (27.3%), A3-A5 = 622 (57.1%); MR3: A1 = 179 (16.4%), A2 = 284 (26.1%), A3-A5 = 210 (28.3%); MR4: A1 = 332 (30.5%), A2 = 447 (41.0%), A3-A5 = 311 (28.5%).

Table 1 shows comparison between respondents according to the country in V4 group on the statements of RMS and MR.

Table 1.

Positive perceptions of respondents on the statements of RMS and MR.

Table 1.

Positive perceptions of respondents on the statements of RMS and MR.

| Factor |

Reputation and social media - RSM |

| RSM1 |

RSM2 |

RSM3 |

RSM4 |

Index RSM |

| RPP |

PL |

0.884 |

0.704 |

0.714 |

0.681 |

0.746 |

| CR |

0.925 |

0.552 |

0.605 |

0.456 |

0.635 |

| SR |

0.870 |

0.593 |

0.636 |

0.599 |

0.674 |

| HU |

0.808 |

0.702 |

0.736 |

0.717 |

0.741 |

| Z-Score for 2 population proportions (Index RSM) |

PL-CR |

6.137***

|

PL-HU |

0.287 |

SR-HU |

2.941**

|

| PL-SR |

3.270**

|

CR-HU |

5.613***

|

SR-CR |

1.758 |

| Factor |

Market risk - MR |

| MR1 |

MR2 |

MR3 |

MR4 |

Index MR |

| RPP |

PL |

0.571 |

0.495 |

0.475 |

0.734 |

0.569 |

| CR |

0.577 |

0.276 |

0.323 |

0.746 |

0.481 |

| SR |

0.630 |

0.494 |

0.444 |

0.679 |

0.562 |

| HU |

0.762 |

0.525 |

0.494 |

0.672 |

0.613 |

| Z-Score for 2 population proportions (Index MR) |

PL-CR |

4.530***

|

PL-HU |

2.136**

|

SR-HU |

2.101**

|

| PL-SR |

0.298 |

CR-HU |

6.575***

|

SR-CR |

3.430***

|

Empirical results showed (see

Table 1) that the country of doing business is significant factors which has effect on the perception of owners and manager on the statement of reputation and social media (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, PL-SR, CR-HU, and SR-HU), and market risk (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, PL-HU, CR-HU, SR-HU, and SR-CR). The statistical hypotheses H_RMS and H_MR were accepted.

Structure of answer in V4 group (n = 1,090): PER1: A1 = 485 (44.5%), A2 = 431 (39.5%), A3-A5 = 174 (16.0%); PER2: A1 = 276 (25.3%), A2 = 438 (40.2%), A3-A5 = 376 (34.5%); PER3: A1 = 276 (25.3%), A2 = 438 (40.2%), A3-A5 = 376 (34.5%); PER4: A1 = 197 (18.1%), A2 = 258 (23.7%), A3-A5 = 635 (58.2%); NSLCH1: A1 = 180 (16.5%), A2 = 247 (22.7%), A3-A5 = 663 (60.8%); NSLCH2: A1 = 138 (12.7%), A2 = 284 (26.1%), A3-A5 = 668 (61.3%); NSLCH3: A1 = 153 (14.0%), A2 = 309 (28.4%), A3-A5 = 628 (57.6%); NSLCH4: A1 = 130 (11.9%), A2 = 271 (24.9%), A3-A5 = 689 (62.3%).

Table 2 shows comparison between respondents according to the country in V4 group on the statements of PER and NSLCH.

Empirical results showed (see

Table 2) that the country of doing business is significant factors which has effect on the perception of owners and manager on the statement of personnel risk (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, PL-SR, CR-HU, SR-HU, and SR-CR), and national support and social change (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, PL-HU, CR-HU, SR-HU, and SR-CR). The statistical hypotheses H_PER and H_NSLCH were accepted.

Structure of perception in V4 group countries (n = 1,090): CSR1: A1 = 234 (21.5%), A2 = 438 (40.2%), A3-A5 = 418 (38.3%); CSR2: A1 = 180 (16.5%), A2 = 447 (41.0%), A3-A5 = 463 (42.5%); CSR3: A1 = 179 (16.4%), A2 = 367 (33.7%), A3-A5 = 544 (49.9%); CSR4: A1 = 168 (15.4%), A2 = 353 (32.4%), A3-A5 = 569 (52.2%); OR1: A1 = 270 (24.8%), A2 = 474 (43.5%), A3-A5 = 346 (31.7%); OR2: A1 = 190 (17.4%), A2 = 383 (35.1%), A3-A5 = 517 (47.5%); OR3: A1 = 260 (23.9%), A2 = 482 (44.2%), A3-A5 = 348 (31.9%); OR4: A1 = 260 (23.9%), A2 = 458 (40.0%), A3-A5 = 372 (34.1%).

Table 3 shows comparison between respondents according to the country in V4 group on the statements of CSR and OR.

Empirical results showed (see

Table 3) that the country of doing business is significant factors which has effect on the perception of owners and manager on the statement of corporate social responsibility (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, PL-SR, PL-HU, CR-HU, SR-HU, and SR-CR), and operational risk (pairwise comparison between: PL-SR, PL-HU, CR-HU, and SR-CR). The statistical hypotheses H_CSR and H_OR were accepted.

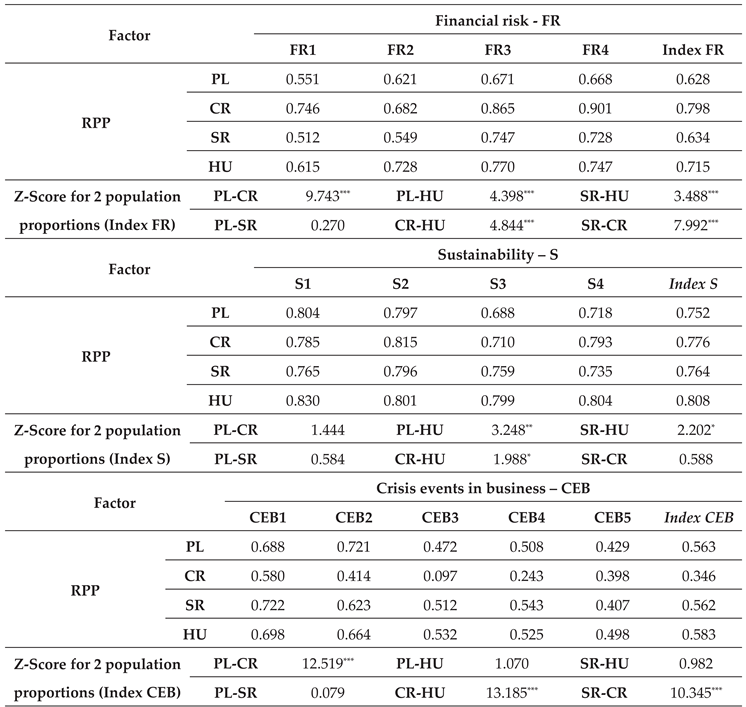

Structure of answer in V4 group (n = 1,090): FR1: A1 = 229 (21.0%), A2 = 453 (41.6%), A3-A5 = 408 (37.4%); FR2: A1 = 271 (24.9%), A2 = 445 (40.8%), A3-A5 = 374 (34.3%); FR3: A1 = 281 (25.8%), A2 = 559 (51.3%), A3-A5 = 250 (22.9%); FR4: A1 = 369 (33.9%), A2 = 474 (43.5%), A3-A5 = 247 (22.6%); S1: A1 = 295 (27.1%), A2 = 575 (52.8%), A3-A5 = 220 (20.1%); S2: A1 = 294 (27.0%), A2 = 582 (53.4%), A3-A5 = 214 (19.6%); S3: A1 = 272 (25.0%), A2 = 527 (48.3%), A3-A5 = 291 (26.7%); S4: A1 = 300 (27.5%), A2 = 535 (49.1%), A3-A5 = 255 (23.4%); CEB1: A1 = 280 (22.7%), A2 = 439 (40.3%), A3-A5 = 371 (34.0%); CEB2: A1 = 271 (24.9%), A2 = 445 (40.8%), A3-A5 = 374 (34.3%); CEB3: A1 = 148 (13.6%), A2 = 253 (23.2%), A3-A5 = 689 (63.2%); CEB4: A1 = 147 (13.5%), A2 = 321 (29.4%), A3-A5 = 622 (57.1%); CEB5: A1 = 169 (15.5%), A2 = 302 (27.7%), A3-A5 = 619 (56.8%).

Table 4 presents a comparison of respondents from the V4 group countries based on their responses to statements regarding Financial Risk (FR), Sustainability (S), and Corporate Ethical Behavior (CEB).

Table 4.

Positive perceptions of respondents on the statements of FR, S, and CEB.

Table 4.

Positive perceptions of respondents on the statements of FR, S, and CEB.

Empirical results showed (see

Table 4) that the country of doing business is significant factors which has effect on the perception of owners and manager on the statement of financial risk (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, PL-HU, CR-HU, SR-HU, and SR-CR); sustainability (pairwise comparison between: PL-HU, CR-HU, and SR-HU); and crisis events in business (pairwise comparison between: PL-CR, CR-HU, and SR-CR). The statistical hypothesis H_FR was accepted, and H_S with H_CEB were partially accepted.

4. Discussion

Our findings are very interesting in the segment of SMEs, specifically in the region of the V4 countries.

The positive perceptions of reputation and social media among Czech (63.5%) and Slovak (67.4%) SMEs are significantly lower than those of Polish (74.6%) and Hungarian (74.1%) SMEs. The perception that corporate reputation plays a significant role in business is more important than social media for SMEs in each country. In Czech SMEs, this element is the most significant (92.5%).

Reputation and social media impact the sustainability of SMEs, as confirmed by other authors. From the results of the study by Ključnikov et al. [

23] and Zieba et al. [

24], it follows that raising awareness of successful business management contributes to its development with an orientation towards the economic, environmental, and social areas.

Stagnation of the market, strong competition, or lack of sales are attributes of market risk that have a stronger effect on Czech SMEs in comparison with Polish, Hungarian, and Slovak SMEs. Only 48.1% of Czech SMEs do not have problems with these attributes. The empirical results showed that Polish and Slovak SMEs have very comparable perceptions of market risk sources (SR: 56.2%/PL: 56.9%). On the other hand, these results in the PL and SR SME segments are statistically of lower intensity than in Hungarian SMEs (HU: 61.3%). The country of doing business is an important factor.

The authors Kim & Vonortas [

26], Stângaciu et al. [

27], and Lopez-Torres et al. [

28], based on their research, consider market risk as the most serious perceived risk in SMEs in the V4 countries and note the impact of market risk on the sustainability of SMEs. Hernandez-Diaz et al. [

29] and Gorondutse et al. [

30] regard the impact of market risk as an important strategic factor in the management of SMEs.

Only 19.9% of Czech SMEs think that employee turnover has no negative impact on their business. More positive perceptions of this statement come from Slovak, Hungarian, and Polish owners and managers. Generally, Czech SMEs also perceive other indicators of personnel risk more negatively, such as employee errors or investments in improving the qualifications of employees, in comparison with other SMEs from the V4 countries.

These results are also confirmed by authors Fraser, Simkins [

45], and Gede Riana et al. [

46], who claim that the quality of human capital in SMEs is linked to successful and competitive business operations. It is important to recognize the risks that affect the quality of human potential in SMEs, and their timely reduction will help prevent crises. Boeske, Murray [

47] and Belas et al. [

48] emphasize the need to enhance the knowledge, skills, and soft skills of managers in this domain.

48.2% of Hungarian SMEs think that national support and legislative changes do not negatively affect their business. More negative perceptions of these factors are held by Czech (28.5%), Polish (32.8%), and Slovak (38.3%) owners and managers. There are significant differences between countries in the V4 region. In this context, over-regulation of the business environment is a more negative indicator than frequent legislative changes. The level of support from national institutions in times of crisis (e.g., COVID-19; Russia-Ukraine conflict) is considered adequate by 48.5% of Polish SMEs and 46% of Hungarian SMEs, but only by 35.2% of Slovak SMEs and 26.8% of Czech SMEs.

Based on the studies processed by authors Slusarczyk, Grondys [

50], Virglerova et al. [

51], Kotaskova et al. [

52], Popp et al. [

53], Musa et al. [

54], and Gorzeń-Mitka [

55], it is possible to state that the instability of laws, frequent changes in laws, the ambiguity of laws, and the unclear and complex legislative framework are among the biggest obstacles to SME business in the V4 countries.

The positive perception of corporate social responsibility in Czech SMEs (43.9%) is significantly lower than in Slovak (50.9%), Polish (59.1%), and Hungarian (61.5%) SMEs. The perception that CSR has a positive impact on financial performance is important for more than 60% of Hungarian SMEs, but only for 33% of Czech SMEs.

Current world trends highlight sustainability as an important element in business management. The European Commission approved the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Other authors, such as Betakova et al. [

2], Metzker et al. [

15], and León-Gómez et al. [

16], declare the sustainability of enterprises as part of competitive performance, development, and efforts to protect the interests of consumers and the environment.

The effectiveness of production capacities, problems with the distribution of products/services, or issues with suppliers are attributes of operational risk that are evaluated the worst in Slovak SMEs. Authors Rózsa et al. [

17] and Małkowska et al. [

19] share the same opinion, i.e., they state that the evaluation and measurement of SME performance is an important element of prosperous businesses and, therefore, it is necessary to change the thinking of SME owners in the financial area. Additionally, authors such as Kocmanová et al. [

20], Tur-Porcar et al. [

21], Pavláková Dočekalová et al. [

22], and Ahmad et al. [

7] declare that key performance indicators help companies achieve sustainability and prevent environmental, economic, social, and corporate governance impacts.

More than 79% of Czech SMEs and more than 70% of Hungarian SMEs confirmed that financial indicators, such as sufficient profit, adequate indebtedness, and no problems with payment obligations, are perceived positively. These results are more positive in Czech and Hungarian SMEs compared with Slovak (63.4%) and Polish (62.8%) SMEs. Authors Agarwal and Ansell [

39], Dumitrescu and Deselnicu [

40], Makovická Osvaldová et al. [

41], and Vandličková et al. [

42] claim that it is also necessary to pay attention to operational risks, especially from the perspective of product risks, process or system failures, failure of production processes, business interruption, accidents, insufficient utilization of production capacities, non-compliance with quality, etc.

More than 80% of Hungarian SMEs perceive that their company is sustainable, and owners/managers understand the concept of sustainable business growth. Generally, the index of sustainability is the highest factor in each country of the Visegrad group. According to authors Belas et al. [

32], Arsic et al. [

34], Heenkenda et al. [

35], Kliuchnikava et al. [

36], financial risk is and will continue to be considered one of the key risks affecting business sustainability in the V4 countries, which impacts the financial performance of the business. Civelek et al. [

33] and Logan et al. [

37] encourage managers to adopt the right approach to financial risk management decisions and to pay the necessary attention to their timely mitigation.

Only 34.6% of Czech SMEs think that crisis events in business (e.g., COVID-19, the Russia-Ukraine conflict) do not have an effect on the company's sustainability. In comparison with other countries in the V4 group, the perception of Czech SMEs is the lowest. In this context, the perception of crisis event indicators in business is most positive among Hungarian SMEs (58.3%). Semenikhina et al. [

56] claim that socially responsible business and risk management are considered key tools for the preventive prevention of crises. Also, Kubas et al. [

59] emphasize the need to focus on prevention. Prevention has a direct connection with management, the benefits of which include increased success in the economic, social, environmental, and psychological areas of business management.

5. Conclusions

The aim of the article was to verify differences in the perception of selected sustainability factors in the SME segment between countries in Central Europe.

The research confirmed significant findings. The country in which business is conducted is a significant factor in the evaluation of perceptions of selected sustainability factors in the SME segment within the business environment of the Visegrad Group. The greatest differences are observed between owners and managers in the evaluation of CSR indicators. The impact of CSR in the Hungarian SME segment (64.9%) is significantly higher than in the Czech SME segment (43.9%). The factor with the most positive responses (according to the index; Slovakia: 76.4% and Hungary: 80.8%) is sustainability.

The processed results are intended for owners and managers of key processes in SMEs not only in Central Europe but also in other European countries and around the world. They focus on the awareness and acceptance of current trends in the global competitive environment, with a special emphasis on the sustainability of SMEs. This includes particularly the identification of stakeholders' needs and values from the perspectives of social, economic, and environmental aspects. Ultimately, this enhances the effectiveness of risk management, prevents business crises, and achieves long-term sustainability and success for SMEs. The findings serve as a useful basis for analyzing the quality of the business environment in Central European countries, educational institutions, and other support organizations that aid in the development and sustainability of businesses in the SME segment.

The case study has the following limitation: The research was conducted in only four countries in Central Europe. The subject of the research was solely the subjective perceptions of owners and managers in the SME segment. The questionnaire covered only selected aspects that affect the sustainability of SMEs. Data collection was carried out using the CAWI methodology, which has certain deficiencies (e.g., questionnaires filled out using a computer). The hypotheses were evaluated using basic statistical methods (descriptive statistics, Z-score).

The authors would like to conduct the research again, using a questionnaire that also includes other important factors such as business ethics, the environmental aspects of entrepreneurship, the level of digitalization in SMEs (e.g., Kliestik et al., [

62]), technological factors of doing business, the level of artificial intelligence application in SMEs (e.g., Valaskova et al., [

63]), and so on. The authors believe that demographic characteristics, such as the size or age of the enterprise, business sector, etc., could significantly affect the perception of factors influencing sustainability in the SME segment.