1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines 'sustainable development' as 'development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs'. To achieve this, three dimensions need to be 'harmonized: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection. The United Nations emphasizes how the term 'sustainable', once linked only to its 'green' meaning, also includes economic and social dynamics. On the basis of these definitions, 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were created, the contents of which can be summarized by the five 'P's: Human welfare (targeting the eradication of poverty and the preservation of dignity), economic well-being and environmental harmony (prosperity viewed through the lens of both financial comfort and ecological balance), tranquility, collaboration (emphasizing the necessity of cooperation among nations and enterprises to fulfill these objectives), and environmental stewardship (regarding the Earth as a valuable resource that must be safeguarded). SDG No. 3 has health as its central element.

In 2018, The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development focuses on the social determinants of mental health and mentions a set of indicators to monitor progress for mental health in the SDG era [

1].

In the sphere of sustainable mental health, where digitalization has also fostered cultural, educational and communicative evolution, we must include those phenomena that concern those who have chosen to take care of the health of their fellow human beings: health workers [

2].

Healthcare workers are among those who, in recent years, have been most exposed to particularly wearisome phenomena, both from a physical and psychological point of view, also as a result of the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

From 2019 to 2021, we witnessed more than 8,000 exits of white-care professionals due to voluntary resignations, in addition to 12,645 due to expiry of fixed-term contracts, retirements, or deaths [

3]. Since 2017 there has been a real explosion of the phenomenon throughout Italy, with a gradually increasing trend. Data for 2020 and 2021 confirmed this trend; 2886 hospital doctors, 39% more than in 2020, left the NHS to pursue their professional activity elsewhere [

4].

Between 2022 and 2023, the number of healthcare professionals who left the public system exceeded 6,000, more than twice as many as in previous years; for 2024 the Anaao-Assomed (the most important union of hospital doctors [

5] and managers in the NHS) estimates that more than 7,000 doctors will leave public hospitals. This is also confirmed by the Meteor project, which has been studying for years in four European countries the reasons for the current abandonment, confirming that one doctor in five is thinking of leaving the hospital, with 10% even wanting to leave the profession altogether [

6].

Among the reasons for this drastic decision are the desire for more flexible working hours, greater professional autonomy, less bureaucracy, and a concrete salary adjustment [

7]. Increasingly, there is a search for a place that preserves, with a view to sustainable work, living and working conditions that support people so that they can develop their professionalism and remain active throughout their lives in a perspective of constant employability, ensuring an appropriate balance between personal and working life and satisfaction for the individual and the organization by defending the 'work-life balance' [

8].

It is noteworthy that the increase in this phenomenon accelerated most after the COVID-19 pandemic; plausibly this event brought to light, even more, the actual shortcomings of the national health system, both in terms of staffing and structure [

9,

10]. Doctors are victims of the global phenomenon better known by the term 'great resignation', the main cause of burnout burnoutees an increasing number of people leaving their jobs [

11].

According to the 11th revision of the WHO's International Classification of Diseases, Burnout is a feeling of exhaustion, alienation or cynical or negative feelings towards one's work, with reduced job performance, resulting from chronic stress in the workplace [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Maslach and Leiter (2000) [

16] refined the components of the Burnout syndrome by proposing a multidimensional approach, i.e. across three dimensions:

- 1.

Increased mental distance from one's work, or feelings of negativity or cynicism related to one's work (cynicism);

- 2.

Feeling of psychic fatigue or exhaustion of energy used in work (emotional exhaustion);

- 3.

Adjustment problems between the person and the job, due to the excessive demands of the latter (reduction in personal fulfilment or effectiveness).

The dimensions comprehensively reflect the interconnectedness of the symptoms of the Burnout definition;

cynicism is a self-defence mechanism from exhaustion and disappointment, which aims to minimize work involvement [

17].

Emotional exhaustion is the result of a condition of recurrent stress (

e.g., emotional and physical), which results in the perception of work demands that are excessive compared to personal resources [

18].

Reduced personal fulfilment or effectiveness is a dimension characterized by the perception of negative feelings such as inadequacy, loss of self-esteem and the resulting feeling of personal failure. The sense of fulfilment and professional effectiveness are extremely important for every individual, because they represent fundamental needs for human motivation to work [

19,

20].

If the working environment does not meet workers' needs, and if shifts are excessively exhausting, there is a reduction in their energy and enthusiasm, with various negative consequences, including a high rate of absenteeism, reduced performance, an increased risk of occupational accidents, depression, anxiety and sleep disorders, which are in turn causes of more complex neuro-psychiatric disorders [

13,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Reduced utilization of human resources is one of the causes of the gap between job demands and the resources needed to do one's job; this can facilitate the onset of adaptive disorders such as job burnout [

25,

26]. Understanding the mechanisms underlying Burnout burnoutial for ensuring the well-being of workers and, consequently, the effectiveness of their performance, thus ensuring better patient care in the health sector [

18]. Workload is one of the main causes of burnout workers often feel overloaded and often fail to perform adequately [

27].

According to the scientific literature, a radical change in the organization of work in the healthcare environment is necessary to significantly reduce the Burnout phenomenon [

28,

29]. Individual empowerment, which is achieved when the working environment enables staff to perform well overall, is one of the mechanisms promoted by empowered organizations [

30].

Aspects that favour the phenomenon of organizational empowerment are the support, learning and professional development opportunities and resources needed to provide safe and effective healthcare, which is also the subject of recent legislation [

31]. Improving the working environment improves organizational commitment levels and employees' feelings of autonomy and self-efficacy, thus reducing the factors underlying burnout [

12].

Based on the above, the aim of our study was to investigate the susceptibility to burnout burnoutedical personnel and the factors influencing the three different dimensions of burnout burnoutsm, emotional exhaustion and reduced personal fulfilment or effectiveness). In a first step, we explored psychosocial factors in healthcare personnel who showed different levels of burnout burnoutmedium and low) and finally assessed the relationship between these and burnout.burnoutgh there is ample knowledge about which mechanisms in the work environment can help prevent the onset of emotional exhaustion, [

e.g. 32, 33] it is still very unclear how this leads to cynicism [

34]. Cynicism, we recall, is a symptomatic expression of the state of burnout burnoutesults in attitudes of apathy and detachment that reduce the quality of healthcare activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

We conducted a cross-sectional study on a group of 1084 physicians (belonging to different specializations including anaesthesia and resuscitation, surgery, emergency medicine, orthopaedics, gynaecology, internal medicine, cardiology, cardiac surgery, urology, dermatology, plastic surgery), distributed in different operating units, both complex and simple, of urban hospitals of the metropolitan city of Palermo. The study was conducted through the administration of an anonymous questionnaire drawn up and distributed on a Google Form platform during working hours. Since the data were obtained in a totally anonymous manner, with informed consent presented at the time of collection, the study, in accordance with World Health Organization [

35] provisions on scientific research, did not require the approval of local ethics committees. A total of 712 physicians from different operating units participated in the survey (participation rate of 65.67%). All doctors were informed of the significance of the study and the confidentiality of the data collected.

2.2. Tool

The questionnaire, structured anonymously in all its components, comprised two macro sections:

- 1.

General biographical and employment section (i.e. information on age, gender, role, also in terms of precariousness, operational unit of employment, etc.).

- 2.

Burnout section containing specific questions and on the organizational variables of the study.

Since some of the scales used do not have Italian validation and have therefore fallen into disuse, the questionnaire was appropriately translated by a native speaker expert.

The measurement scales used for the study variables are described below:

2.3. Burnout

Maslach, Jackson and Leiter's version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) scale [

36], customized for medical personnel, developed by the Pontifical Lateran University was used (Appendix 1). This version includes 22 items divided into the three different Burnout dimensions (see Appendix A). For each item, physicians indicate their level of agreement using a point scale from 0 (

never) to 6 (

every day).

Using this instrument, burnoutburnout read either dichotomously (present or absent) [

37], or as a continuous variable being a gradually developing process (considering the various levels, low, moderate and high) and, moreover, the results can be expressed either by considering the individual dimensions or by considering a single outcome of the three subscales [

38].

2.4. Organizational Empowerment

The CWEQ-II (Job Efficacy Conditions Questionnaire-II) [

39], measures the three main components of empowerment through 19 items, with a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The information dimension (inherent to job titles) was not considered for statistical purposes because the sample examined was homogeneous.

2.5. Workload and Labour Control

The magnitude of the workload is particularly important in terms of the Development of Burnout. When work demands exceed human limits, the most likely consequence is emotional exhaustion. Huuhtanen and Kalimo (2005) found that a particularly high workload is associated with high emotional exhaustion [

40,

41].

The control dimension encompasses people's perceived ability to influence decisions about their work, to exercise personal autonomy and to access resources (e.g. social support, rewards) to get the job done [

42].

These items were analyzed with the Areas of Worklife - AWS scale of Leiter and Maslach [

43].

2.6. Quality of the Team

A questionnaire for the intensive care unit, customized for the medical staff, was used to explore the quality of teamwork [

44].

The version used included two subscales, one for communication and one for the perception of team effectiveness. The items were rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Relationship between empowerment and burnoutburnoutling that empowerment is a set of actions aimed at strengthening the employee's position of choice, representing a prevention mechanism by reducing the relationship between cynicism and emotional exhaustion, with other prevention strategies including the enhancement of communication and team effectiveness aspects, according to Deci and Ryan [

45], the goal of interpersonal relationships is not only the achievement of work objectives, but also the satisfaction of the individual's intrinsic needs for competence and autonomy.

In our study, we wanted to consider the dimensions of burnoutburnoutultaneous, and evaluate their relationship with elements of empowerment, such as communication and team effectiveness, to understand how they can positively influence them by preventing burnoutburnoutistical analysis

As anticipated by Maslach et al. (2000) and applied by Wickramasinghe et al. (2018), it is possible to translate the multifacetedness of burnoutburnout dichotomous view in order to account for the extent of the problem in terms of susceptibility and prevalence [

36,

37,

46,

47]; therefore, it was chosen to process the obtained data on Burnout status by dividing the sample into two groups: non-prone (NP), with an overall low test result, and susceptible (P), with an overall moderate/high test result.

The cut-off between the two levels was established based on the studies by Brenninkmeijer and Van Yperen (2003) [

48] and Roelofs et al. (2005) [

49], according to which an individual is considered predisposed when he/she presents a 'moderate/high' MBI test score in at least two of the three dimensions. This decision rule, which is based on clinically validated cut-off points, allows the MBI to be translated into a dichotomy that can be used to diagnose burnoutburnouteliability of the tests used was assessed using Cronbach's Alpha coefficient (α) [

50].

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed to verify the usability of the responses obtained to the items. The responses were then analyzed with a common factorial collection model. The Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, cut-off ≤ .08), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI, cut-off ≥ .90) and the Incremental Fit Index (IFI, cut-off ≥ .90) [

51,

52] were used to assess the performance of the model.

To test the differences between the averages of the two groups, an ANOVA (between variance) analysis was conducted [

53].

Pearson's coefficient was used to ascertain the correlation between the variables [

54].

To assess the relationship between Burnout dimensions and empowerment elements and their positive influence on Burnout prevention, we performed regression analyses (moderation and mediation) [

55].

The selected control variables were contained in the first part of the questionnaire and were: age, role, area of specialization.

Using the procedure of Aiken and West, we studied the regression line of the independent variable on the dependent variable for high and low levels of the moderator [

56].

Bootstrap-corrected 95 per cent confidence intervals were also obtained to study, specifically, the relationship between group communication and personal effectiveness [

57].

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 10.1.0 software (264).

3. Results

A total of 712 doctors from different operating units participated in the survey, with a participation rate of 65.67%. It was possible to use 614 questionnaires, representing a response rate of 86.21%. A total of 98 questionnaires were discarded as incomplete. The response rate for each unit ranged from 53.01% to 100%.

In about 524 questionnaires (85.49%), the age of the compilers was between 25 and 55 years, with a greater percentage of female subjects, amounting to about 353 (67.41%); the major specialist areas represented were those pertaining to the emergency and surgery macro-departments, with about 300 compilers (57.09%); the average length of employment of the overall sample at the facility was over 10 years, with seniority of between 1 and 3 years for about 251 subjects (41.22%), between 4 and 10 years for 160 subjects (25.7%) and over 10 years of service for 203 subjects (32.97%).

On the average of the total sample (N=614), the results revealed a moderate level of susceptibility to burnoutburnoute three dimensions considered, namely:

- -

Increased mental distance from one's work or feelings of negativity related to one's work (cynicism): M = 1.57, SD = 1.33, cut-off range ≤ 1.03 - ≥ 2.21;

- -

Feeling of exhaustion or depletion of energy used in work (emotional exhaustion): M = 2.36, SD = 1.52, cut-off range ≤ 2.02 - ≥ 3.20;

- -

Adjustment problems between the person and the job, due to the excessive demands of the latter (reduction of personal fulfilment or effectiveness): M = 4.60, SD = 1.02, cut-off range ≤ 5.03 - ≥ 4.02.

In 54.73% of the predisposition cases all dimensions of burnoutburnoutresent, in 58.01% of the cases a reduction in personal fulfilment was manifested.

Comparison of physicians not predisposed and predisposed to burnoutburnoutn the two groups, the combination of the empowerment variables with the dimension of emotional exhaustion revealed statistically significant variations.

For the group of physicians with moderate/high levels of emotional exhaustion, the level of empowerment was found to be inversely proportional, especially for the dimensions related to workload, which was found to be excessive in the responses, work control, opportunities (expressing a reduced possibility to acquire new skills and knowledge and to use existing skills and knowledge at work); with regard to the team (community) dimension, although it was found to be deficient with regard to communication, no significant difference was found with regard to perceived effectiveness in terms of teamwork and patient care, which was also found to be deficient.

Statistically significant variations were also found between the two groups in the levels of negative feelings and alienation from work; the level of empowerment was low in doctors with moderate/high negative feelings.

3.1. Validity and Reliability of Measurements and Correlation Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the 10-factor model fitted the data well: χ2 (df = 359) = 753.6, IFI = .90, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .06. In contrast, the single-factor model showed a poor fit: χ2 (df = 404) = 2549.1, IFI = .44, CFI = .44, RMSEA = .13. Consequently, significant support was found for the 10-factor model: Δχ2 (Δdf = 45) = 1795.5, p < .001. The measures demonstrated good reliability coefficients (0.82-0.92). Cronbach's Alpha values for all measures ranged from .67 to .88, indicating strong reliability and internal consistency of the items in the measures. Correlation analysis indicated negative relationships between the three components of empowerment (i.e., opportunities, resources, and support) and the three dimensions of burnoutburnoutonal exhaustion, r = -.173, -.267, -.207, p < .01, respectively; cynicism, r = -.268, -.222, -.295, p < .01, respectively; personal ineffectiveness, r = -.358, -.289, -.293, p < .01, respectively). Workload showed positive relationships with emotional exhaustion (r = .492, p < .01) and cynicism (r = .278, p < .01). Job control, team communication and team effectiveness were negatively related to all dimensions of burnoutburnoutonal exhaustion, r = -.239, -.226, -.302, p < .01, respectively; cynicism, r = -.324, -.357, -.207, p < .01, respectively; personal ineffectiveness, r = -.182, -.247, -.296, p < .01, respectively).

3.2. Moderation and Mediation Analysis

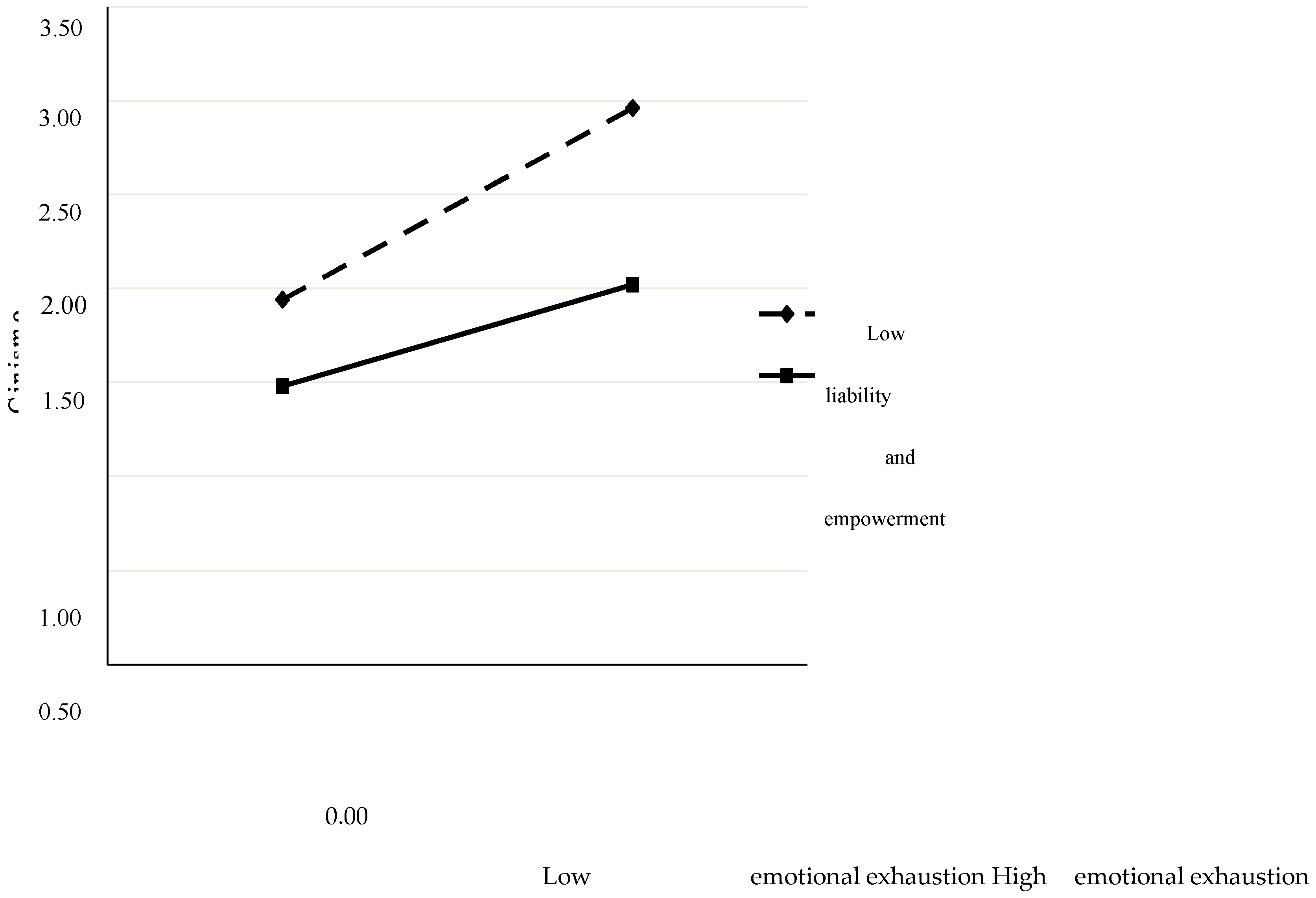

The results established that empowerment significantly moderates (β = -0.12, p < 0.05) the relationship between emotional and work exhaustion and feelings of estrangement from work (results are shown in

Table 2).

Regression analyses concerning the relationship between feelings of distancing from work and emotional exhaustion showed that the two dimensions were simultaneous, especially if empowerment had a low value (simple slope for a low empowerment value = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.36-0.61, t = 7.75, p<.001). When the level of empowerment was high (= 0.29, 95% CI = -0.15-0.43, t = 4.12, p<.001), the relationship was statically weaker.

Mediation analyses revealed that group communication has a positively significant indirect effect on the perception of personal efficacy (-.22 [95% CI = -.10, .35]). (Results are shown in

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The current crisis of medical staff employed in public hospitals, where, due to a lack of human, organizational and instrumental resources, an exodus to private facilities has been taking place for years, the impact of which in the media has exacerbated the working difficulties of doctors, who are dissatisfied with their work, partly sees its reasons in the phenomenon of burnoutburnouth-risk event for any working organization, both in terms of staff health and the activity and productivity of the sector, especially the health sector [

58].

The impetus for this work therefore came from the perspective of investigating the reasons why medical personnel, employed in public facilities, do not achieve a sustainable working condition that facilitates the development of their professionalism, thus ensuring an adequate work-life balance, and leave their jobs [

59,

60].

Doctors increasingly find themselves managing shifts that are extended beyond their scheduled hours, psychologically and physically exhausting, with alterations in their psycho-physical balance, which have repercussions on the quality of their work [

59]. This phenomenon is also reflected in the international literature, where it is commonplace that higher remuneration and a superior organic and structural organization favor the job satisfaction of teams, with a bearable perception of the workload [

61].

In our study, we observed that in physicians working in emergency-urgency settings, the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and moderate/high negative feelings are associated with a low level of almost all organizational empowerment variables (job control, community, resources), with a high predisposition to Burnout syndrome.

Workload does not seem to have statistically strong associations, probably because it is secondary to the quality of work and the working environment.

Correlation analyses confirmed the positive preventive role of empowerment on both emotional exhaustion and negative feelings of alienation from work. Furthermore, it was found that the more workload is perceived as excessive and the more control is lacking, the higher the level of burnoutburnoutame analysis also revealed an indirect role of the team's communicative and collaborative dimension; personal ineffectiveness is in fact reduced by good teamwork from the communication point of view, especially in terms of quality. This result reflects the clinical application of Nesh's mathematical equilibrium, confirming the fundamental importance of good interpersonal relations between the members of a team, whose synergistically coordinated activity can lead to an improvement in the quality of care [

62].

The practical implications of this study have substantial significance for healthcare institutions and their management. One of the key management issues is the importance of recognizing the negative impact of burnoutburnouttors' work [

63].

Identifying the risk factors underlying the Burnout phenomenon is an essential step in planning appropriate prevention interventions to ensure the protection of workers' health and safety [

64].

A 2010 WHO document states that the most accurate and objective way of assessing work-related stress is a combination of several instruments, including objective measures of workload and observations of working conditions, compared with information provided by workers [

65].

The concept of work-related stress is found in the contents of the 2004 European framework agreement, transposed in Italy with the interconfederal agreement of 09/06/2008, where stress is defined as a

"condition ... consequence of the fact that some individuals do not feel able to meet the demands or expectations placed on them' [

66]. When such demands and expectations are work-related, stress is work-related. However, not all manifestations of stress at work can be considered work-related. Work-related stress is caused by dysfunctions in work organization, with repercussions on staff behavior (such as negative health effects, absenteeism) and consequently on the quality of care [

67].

In fact, staff and facility shortages are the input for these behaviors on the part of medical staff, who are exhausted by shortages that lead to considerable psycho-physical stress and riskiness [

68]. This study adds something more by showing the protective role of empowerment that buffers the effect of burnoutburnoutially in light of the physician exodus phenomenon discussed above.

Another important finding is the importance of interpersonal communication that precedes both the psychosocial well-being of doctors and the risk of clinical errors.

When it comes to corporate prevention strategies, the correct execution of a preliminary assessment, in addition to producing a risk score, makes it possible to understand which criticalities, if any, and the corrective actions to be implemented for the company, the organizational partitions or homogeneous groups. Each criticality leads to the identification of the corresponding corrective action to be activated, consistent with the characteristics and modalities of the company [

69].

The activation of tools for worker participation in company decisions and training interventions for the prevention of work-related stress risk, as well as specific learning paths, complement and make effective many of the corrective actions [

70].

Remedial measures may also include solutions to individual cases, which also have an impact on the group. The introduction of personnel management measures, for example, can solve work-life balance difficulties, helping to reduce absenteeism, unpredictable work overload, relational difficulties and ensuring productivity. In cases where the stress condition cannot be further reduced by organizational measures, health surveillance protects individuals with illnesses that are likely to worsen under the continuous stressful stimulus [

71].

The verification of the effectiveness of the corrective actions planned and implemented based on the criticalities found, envisages the assessment through the reapplication of the tool adopted with the preliminary assessment. To verify the effectiveness of the parameters found to be critical, it is necessary to proceed with the involvement of all the contact persons envisaged for the preliminary assessment, possibly integrated with others who were the subject of the corrective actions [

72].

In the specific case under study, a better use of the company's economic resources, to ensure a suitable working environment for doctors, adequate remuneration and protection from risks, could contain the onset of burnoutburnoute flight from public hospitals.

Limitations of the Study

However, our study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample used consisted only of doctors who voluntarily participated in the survey, which limits the generalizability of the results. The questionnaire, although structured on validated scales, included answers based on a self-report (self-assessment), which may generate a bias related to the preference and method used [

73]. The use of numerical data such as the number of health services, in relation to the number of employees, shift hours, etc. could reduce this bias.

5. Conclusion

Considering the above, our study wanted to offer concrete support for the development of the concept of sustainable work, which must be achieved without compromising the ability of future generations to enter or remain in the labor market, avoiding the waste of human and environmental resources, and investing in skills, innovation and relationships.

In the future, interventions are desirable to change the current lack of flexibility in the organization of work, in the absence of innovative corporate welfare tools, and especially in view of the process of progressive feminization of the profession; a reshaping of salaries, which are often not in line with the labor contracts signed in several EU countries; a greater enhancement of the knowledge and skills of professionals in clinical governance processes; a better guarantee of career paths and growth opportunities for employed doctors.

Directives along these lines have already been issued in some European hospitals, where, specifically, a number of initiatives have been taken to establish less convulsive performance schedules, allowing autonomous time management that promotes a better work-life balance, limiting excessively long shifts, implementing team self-management and promoting specific training for managers in 'empathic leadership', aimed at encouraging regular interaction between governance and employees [

74,

75]. These initiatives also highlight which specific interventions can improve and prevent the phenomenon of burnoutburnoutlthcare workers, which we have identified as one of the current causes of inefficiency in public hospitals.

References

- Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development [published correction appears in Lancet. 2018 Oct 27;392(10157):1518]. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1553-1598. [CrossRef]

- Asi YM, Williams C. The role of digital health in making progress towards Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 in conflict-affected populations. Int J Med Inform. 2018;114:114-120. [CrossRef]

- https://www.anaao.it/content.php?cont=31794.

- https://www.anaao.it/content.php?cont=29734.

- https://www.anaao.it/content.php?cont=34509.

- De Vries N, Lavreysen O, Boone A, et al. Retaining Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review of Strategies for Sustaining Power in the Workplace. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(13):1887. Published 29 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- https://www.anaao.it/content.php?cont=35046.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. [CrossRef]

- Cannizzaro E, Cirrincione L, Malta G, et al. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency on Alcohol Use: A Focus on a Cohort of Sicilian Workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4613. Published 2023 Mar 5. [CrossRef]

- Cirrincione L, Plescia F, Ledda C, Rapisarda V, Martorana D, Lacca G, Argo A, Zerbo S, Vitale E, Vinnikov D, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: New Prevention and Protection Measures. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4766. [CrossRef]

- https://www.anaao.it/content.php?cont=31117.

- Cherniss C. Professional burnout in human service organizations. New York: Praeger 1980.

- Freudenberger H. Burnout: The high cost of achievement. New York: Anchor Press 1980.

- Maslach C, Leiter PL. The Truth about Burnout. San Francisco: Jossey Bass 1997).

- https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases.

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103-111. [CrossRef]

- Dulko D, Zangaro GA. Comparison of Factors Associated with Physician and Nurse Burnout. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57(1):53-66. [CrossRef]

- Maslach C. Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2003; 12: 189-92. [CrossRef]

- Dulko D, Kohal BJ. How Do We Reduce Burnout In Nursing?. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57(1):101-114. (Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper 1954). [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli W, Enzmann D. Girault N. Measurement of burnout: A review. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, Eds. Professional Burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis 1993; pp. 199-215.

- Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Effects of hospital staffing and organizational climate on needlestick injuries to nurses. Am J Public Health 2002; 92(7): 1115-9. PMID: 1208469. [CrossRef]

- Glasberg AL, Eriksson S, Norberg A. Burnout and stress of conscience among healthcare personnel. J Adv Nurs 2007; 57(4): 392-403. PMID: 17291203. [CrossRef]

- Lo Coco D, Cupidi C, Mattaliano A, Baiamonte V, Realmuto S, Cannizzaro E. REM sleep behaviour disorder in a patient with frontotemporal dementia. Neurol Sci. 2012;33(2):371-373. [CrossRef]

- Cirrincione L, Plescia F, Malta G, et al. Evaluation of Correlation between Sleep and Psychiatric Disorders in a Population of Night Shift Workers: A Pilot Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3756. Published 2023 Feb 20. [CrossRef]

- Leiter MP, Day A, Oore DG, Spence Laschinger HK. Getting better and staying better: assessing civility, incivility, distress, and job attitudes one year after a civility intervention. J Occup Health Psychol 2012; 17(4): 425-34. PMID: 23066695. [CrossRef]

- Marin MF, Lord C, Andrews J, et al. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2011; 96(4): 583-95. PMID: 21376129. [CrossRef]

- Leiter MP, Maslach C. Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In: Perrewé P, Ganster DC, Eds. Research in occupational stress and wellbeing. Oxford: Elsevier 2003; pp. 91-134. [CrossRef]

- Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J, Wilk P. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Structural and Psychological Empowerment on Job Satisfaction of Nurses. Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting. Denver: CO 2002.

- Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J, Wilk P. Workplace empowerment as a predictor of nurse burnout in restructured healthcare settings. Longwoods Review 2003; 1: 2-11).

- Kanter RM. Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: Basic Books 1977) (21. Kanter RM. Men and Women of the Corporation. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books 1993.

- Albano GD, Rifiorito A, Malta G, et al. The Impact on Healthcare Workers of Italian Law n. 24/2017 'Gelli-Bianco' on Patient Safety and Medical Liability: A National Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8448. Published 2022 Jul 11. [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben JR, Rathert C, Williams ES. Emotional exhaustion and medication administration work-arounds: the moderating role of nurse satisfaction with medication administration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38(2):95-104. [CrossRef]

- Almost J, Laschinger HK. Workplace empowerment, collaborative work relationships, and job strain in nurse practitioners. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(9):408-420. [CrossRef]

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52: 397-422. PMID: 11148311. [CrossRef]

- https://extranet.who.int/kobe_centre/sites/default/files/pdf/WHO%20Guidance_Research%20Methods_Health-EDRM_6.4.pdf.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press 1996.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Shanafelt TD. Defining burnoutburnoutichotomous variable. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):440-441. [CrossRef]

- Soares JP, Lopes RH, Mendonça PBS, Silva CRDV, Rodrigues CCFM, Castro JL. Use of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Public Health Care Professionals: Scoping Review. JMIR Ment Health. 2023;10:e44195. Published 2023 Jul 21. [CrossRef]

- Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J, Wilk P. Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: expanding Kanters model. J Nurs Adm 2001; 31(5): 260-72. PMID: 11388162. [CrossRef]

- Kouvonen, A., Toppinen-Tanner, S., Kivisto, M., Huuhtanen, P., & Kalimo, R. (2005). Job characteristics and burnoutburnoutaging professionals in information and communications technology. Psychological Reports, 97(2), 505-514. [CrossRef]

- Leiter PM, Maslach C. Preventing burnoutburnoutilding engagement Team member's workbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, Inc. 2000) (32. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Areas for Worklife Scale Manual. In: Centre for Organizational research and development. 4th. Wolville, NS, CA: Acadia University 2006).

- de Lange, A. H., Taris, T. W., Kompier, M. A. J., Houtman, I. L. D., & Bongers, P. M. (2003). 'The very best of the millennium': Longitudinal research and the demand-control-(support) model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(4), 282-305. [CrossRef]

- Leiter PM, Maslach C. Preventing burnoutburnoutilding engagement Team member's workbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, Inc. 2000) (32. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Areas for Worklife Scale Manual. In: Centre for Organizational research and development. 4th. Wolville, NS, CA: Acadia University 2006.

- Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, Gillies RR, Devers KJ, Simons TL. Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse-physician questionnaire. Med Care 1991; 29(8): 709-26. PMID: 1875739. [CrossRef]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York: Platinum Press 1985. [CrossRef]

- Guseva Canu I, Marca SC, Dell'Oro F, et al. Harmonized definition of occupational burnoutburnouttematic review, semantic analysis, and Delphi consensus in 29 countries. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2021;47(2):95-107. [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe ND, Dissanayake DS, Abeywardena GS. Clinical validity and diagnostic accuracy of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey in Sri Lanka. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):220. Published 2018 Nov 20. [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer V, VanYperen N. How to conduct research on burnoutburnouttages and disadvantages of a unidimensional approach in Burnout research. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:16i-20.

- Roelofs J, Verbraak M, Keijsers GPJ et al. Psychometric properties of a Dutch version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI- GS) in individuals with and without clinical burnoutburnouts Health 2005; 21:17-25.

- Bujang MA, Omar ED, Baharum NA. A Review on Sample Size Determination for Cronbach's Alpha Test: A Simple Guide for Researchers. Malays J Med Sci. 2018;25(6):85-99. [CrossRef]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modelling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods 1998; 3: 424-53. [CrossRef]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press 2005.

- McHugh ML. Multiple comparison analysis testing in ANOVA. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2011;21(3):203-209. [CrossRef]

- Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(5):1763-1768. [CrossRef]

- Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39-57. [CrossRef]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London: Sage 1991.

- Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav Res 2004; 39(1): 99-128. PMID: 20157642. [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman PJ, Bridgeman MB, Baron J. Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(3):147-152. [CrossRef]

- https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2023/10/27/in-sicilia-i-medici-fuggono-dagli-ospedali-pubblici-verso-le-cliniche-private-la-protesta-di-sindaci-e-pazienti-sanita-al-collasso/7335286/.

- Cirrincione L, Plescia F, Malta G, et al. Evaluation of Correlation between Sleep and Psychiatric Disorders in a Population of Night Shift Workers: A Pilot Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3756. Published 2023 Feb 20. [CrossRef]

- Malta G., Fruscione S., Albano G.D., Zummo L., Zerbo S., Coco D.L. (2023). Shift work and altered sleep: a complex and joint interaction between neurological and occupational medicine 10.3269/1970-5492.2023.18.6.

- Dinibutun SR. Factors Affecting Burnout and Job Satisfaction of Physicians at Public and Private Hospitals: A Comparative Analysis. J Healthc Leadersh. 2023;15:387-401. Published 2023 Dec 4. [CrossRef]

- Itchhaporia D. Game Theory, Health Care, and Economics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(15):1542-1543. [CrossRef]

- Garcia CL, Abreu LC, Ramos JLS, et al. Influence of Burnout on Patient Safety: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Kaunas). 2019;55(9):553. Published 2019 Aug 30. [CrossRef]

- Burton, J., & World Health Organization (2010). WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices. World Health Organization.

- Zoni S, Lucchini RG. European approaches to work-related stress: a critical review on risk evaluation. Saf Health Work. 2012;3(1):43-49. [CrossRef]

- Bhui K, Dinos S, Galant-Miecznikowska M, de Jongh B, Stansfeld S. Perceptions of work stress causes and effective interventions in employees working in public, private and non-governmental organizations: a qualitative study. BJPsych Bull. 2016;40(6):318-325. [CrossRef]

- Gray BM, Vandergrift JL, Barnhart BJ, et al. Changes in Stress and Workplace Shortages Reported by U.S. Critical Care Physicians Treating Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(7):1068-1082. [CrossRef]

- Persechino B, Valenti A, Ronchetti M, et al. Work-related stress risk assessment in Italy: a methodological proposal adapted to regulatory guidelines. Saf Health Work. 2013;4(2):95-99. [CrossRef]

- Cohen C, Pignata S, Bezak E, Tie M, Childs J. Workplace interventions to improve well-being and reduce burnoutburnoutrses, physicians and allied healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e071203. Published 2023 Jun 29. [CrossRef]

- Corradini, I., Marano, A., & Nardelli, E. (2016). Work-Related Stress Risk Assessment: A Methodological Analysis Based on Psychometric Principles of an Objective Tool. SAGE Open, 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Forman-Dolan J, Caggiano C, Anillo I, Kennedy TD. Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9954. Published 2022 Aug 12. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J Manage 1986; 12: 531-44. [CrossRef]

- Peter, K. (2020). Work-related stress among health professionals working in Swiss hospitals, nursing homes and home care organizations: an analysis of stressors, stress reactions and long-term consequences of stress at work among Swiss health professionals. [Doctoral Thesis, Maastricht University]. Ridderprint. [CrossRef]

- Adam D, Berschick J, Schiele JK, et al. Interventions to reduce stress and prevent burnoutburnoutlthcare professionals supported by digital applications: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1231266. Published 25 October 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).