1. Introduction

Climate news coverage prompted the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and intensified global scientific research on greenhouse gas emissions. However, despite the media’s milestone achievement inspiring the formation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), media participation in climate change issues tends to focus on the impacts of the crisis while neglecting climate action (Swain 2014). Knowledge exchange and communication are key targets in climate action as encapsulated in the Sustainable Development Goals. Climate change coverage is typically overshadowed by other issues, limiting public engagement in climate action. This is particularly true of the media in Canada which has not fully utilized its role in amplifying action to ensure healthy soils as a crucial part of climate change mitigation.

The media plays a critical role in fostering understanding and inspiring behavioral and social change, as demonstrated extensively in the context of health communication such as HIV/AIDS (Miller, 1998). The significance of raising individual and wider public awareness about the adverse effects of climate change is well-documented in the literature (Bontempo et al., 2021). Nations around the world must do more to ensure the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices that enhance carbon sequestration (Masud et al., 2017). Globally, soils are under threat. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s 2015 “Status of the World’s Soil Resources” report, although there are some reasons to be hopeful in certain areas, most of the world’s soil is rated as fair, poor, or very poor. Currently, about 33% of arable land is considered to be moderately to highly degraded.

In Canada, the agri-food industry contributed 6.8% or $134.9 billion of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP), with primary agricultural production accounting for approximately one-quarter of this contribution (Statistics Canada, 2021). Agriculture is practiced nationwide but mainly concentrated in Ontario, Quebec and the Prairies. The Ontario government released its Agricultural Soil Health and Conservation Strategy, the New Horizons, in 2018. This strategy aims to ensure agricultural soil conservation efforts until 2030. It involves participation from farmers and industry partners on four main themes: soil management, soil data and mapping, soil evaluation and monitoring, and soil knowledge and innovation. In 2023, the Soil Conservation Council of Canada released the National Soil Health Strategy draft confirming efforts by the Federal Government to achieve sustainable food production, enhanced biodiversity and cleaner air and water for present and future generations. Although the relevance of media is not intricately highlighted in the draft strategy, the significance of collaboration and communication between stakeholders is prioritized. In December 2023, however, the Canadian Journal of Soil Science joined multiple scientific journals in publishing the statement from 200 medical journals that “the environmental crisis is now so severe as to be a global health emergency” (Time to…, 2023:i-iii).

Certainly, the media can serve as a forum for discussing climate change and other issues of common concern, offering an interpretive system for societies (Schäfer et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2013). Its role in climate change communication helps shape how information about climate change is framed and accepted by the public (Okoliko & de Wit, 2020). The media’s coverage of climate change as a human security threat, as acknowledged by the IPCC, has drawn global interest and influenced media trajectories in different jurisdictions (IPCC, 2014).

Effective media framing of climate change should include highlighting the social impacts and benefits of mitigation efforts, experienced collectively and individually (Archer & Rahmstorf, 2009). Relatable stories illustrating the persons and places affected by climate change and their value, particularly regarding livelihoods and food security issues, can drive climate action (Dupar, 2016). Journalists play a vital role in identifying and visualizing environmental risks and assuming the responsibility of issue sponsorship (Hansen, 1994). Their moderation of climate change dialogues can shape public perception and engagement (UN, n.d).

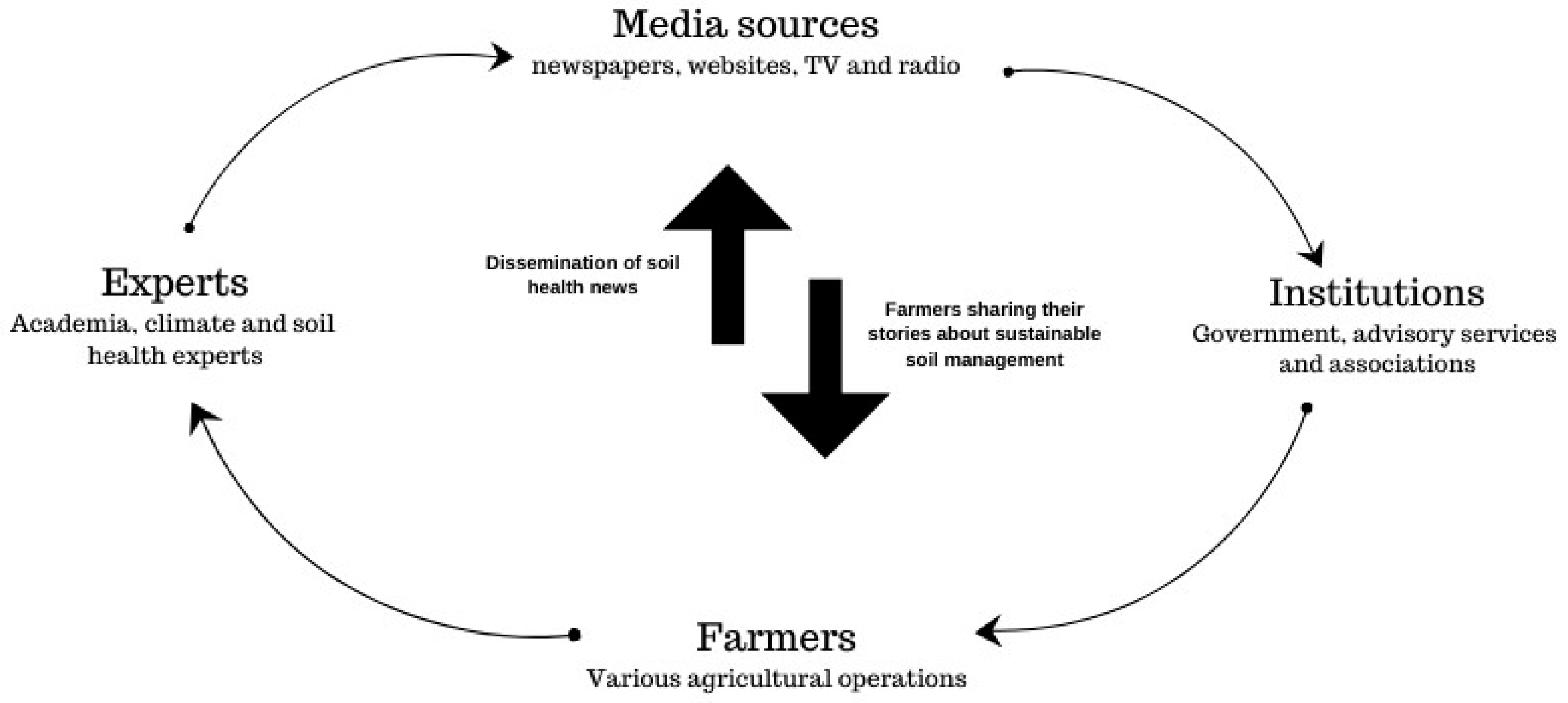

Media for social and environmental change appreciates individual behavioural change communication, but it also requires looking beyond farmer adoption of management practices by investigating socio-technical innovations and policies impacting soil nutrients, plants and animals as well as human-environment interactions. Media can be useful to the assessment of dynamic and influential social processes and knowledge-sharing interactions using communication tools such as television, radio, newspapers, and social media that can, in turn, shape farmers’ understanding, adoption (and non-adoption) and adaptation of soil health management practices.

“Information provided by different mass media is critical in agricultural development because it is a tool for communication between research, extension officers, farmers and all stakeholders in the agricultural sector”.

(Busungu et al 2019:253)

This paper examines recent media coverage in Canada of climate change mitigation efforts, paying particular attention to farming soil health practices in Ontario. The media traditionally shapes public opinion and influences stakeholders’ perceptions of climate change mitigation efforts (Bontempo et al., 2021; Trumbo, 1996; Parks, 2020). News outlets need to disseminate information and increase awareness about the significance of soil health in climate change mitigation, as Milfont et al. (2020) highlight. This can help foster public engagement and inspire collective action. Moreover, the media should fulfill the role of watchdogs, holding policymakers accountable for their decisions regarding soil health and climate change mitigation. Investigative journalism and reporting have the power to uncover environmental degradation, conservation and other issues surrounding soil health, thereby drawing farmers’ and policymakers’ attention. (Bethge et al., 2018). Media coverage of soil health-related climate change mitigation is relevant to Canada’s commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 as per the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act of 2021. Therefore, this paper’s objectives are to (i) determine how the media sources and reports soil health-related climate change mitigation information, and (ii) to discuss how media coverage of soil health affects climate change mitigation action.

2. Literature Review: Climate Change and Soil Health

Climate change refers to long-term modifications in Earth’s temperatures and weather conditions, which can be attributed to natural factors such as volcanic eruptions or solar radiation, as well as anthropogenic actions since the 1800s, largely driven by the combustion of fossil fuels (UN, n.d). Climate is characterized by patterns in weather over time, while weather represents the current atmospheric state (Sanderson, 2015; Alberta Environment, 2007). Hence, climate change is analyzed by examining average weather fluctuations over a minimum of 30 years, whereas short-term variations are referred to as climate variability, which can cause short-lived shifts in temperatures, precipitation patterns, and weather conditions (Palmer, 2019; NOAA, 2021).

The evidence of climate change includes a global temperature increase of 1.5°C since the 19th Century (NASA, n.d) and a rise in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as heat waves, hurricanes, and wildfires (IPCC, 2022). Additionally, the IPCC and NASA data show that atmospheric CO2 concentrations have risen by over 40% since the Industrial Revolution and global sea levels have increased by 8 inches (21 cm) since 1880, with half of that rise occurring in the last 25 years. The Arctic Sea ice has declined by 10% since 1979 (IPCC, 2019). Furthermore, the ocean’s top 2,300 feet (700 meters) has warmed by 0.2°C since 1969. All of these issues are entirely relevant in Canada; we highlight here the crisis facing soil health and agricultural lands.

3. Soil Health-Related Climate Change Mitigation

Soil health is crucial for supporting terrestrial life as it functions as a living ecosystem. It plays a significant role in global food security, water quality, human health, and biodiversity. Zhang et al. (2019) projects that improving soil health can enhance global food security by 22% and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 17%. Sustainable soil management practices sequester carbon, mitigating climate change (Hou, 2022). Healthy soils contribute to better water quality by reducing nutrient runoff by up to 93% compared to degraded soils. They can absorb more water, minimizing erosion and filtering pollutants, improving surface and groundwater quality (Blanco-Canqui and Lal, 2009).

Bouma (2022:1) observes that it is a “painful fact that after many decades of research, existing knowledge about improved soil management has not resulted in application in practice by sufficient numbers of farmers.” Within this context, agricultural soil health, and the people who manage that agricultural soil, are of major importance.

Soil health is defined as “the continued capacity of the soil to function as a vital living system, within ecosystem and land-use boundaries, to sustain biological productivity, maintain the quality of the air and water environment, and promote plant, animal and human health” (Lehman et al., 2015, 990). Soil health implicates the soil’s physical, chemical and biological, as well as how these relate to its functionality and sustainability (Marshall et al., 2021). The management of soil health has a social side, in other words, the people such as farmers who directly know about and manage soils and the institutions (governance, policies and initiatives) within society that influence soil health management practices (de Boon et al., 2022). These practices include conservation agriculture, cover cropping, residue mulching, intercropping, and mixed management systems associated with increasing soil health and building soil organic matter (SOM) (Congreves et al., 2015; Lal, 2020). Rebuilding the soil organic matter of degraded soils leads to increased soil water retention, which makes both the plant and the agricultural system more climate resilient (Chahal et al. 2021).

Soil is critical to climate change mitigation as it stores up to fivefold as much carbon as the atmosphere, representing the largest terrestrial carbon sink (Hou, 2022). This process, called soil carbon sequestration, imperatively mitigates climate change (Ussiri & Lal, 2013). It has long been recognized that any changes in farming practices are, however, shaped by several interacting biophysical, socio-economic, institutional (“rules of the game”) and cultural conditions (McCorkle, 1989; Vanclay & Lawrence, 1994; Harrison et al., 1998). This is the bridge between climate change and soil health that communication processes and products connect. The media plays a key role in communicating about socio-technical and regulatory interventions in climate change and can be influential in action on soil health.

4. Media Communication and Awareness

Soil health communication has recently increased worldwide due to mounting concerns for degraded soils, deteriorating soil quality, and its subsequent impacts on nutrition, food security, and public health (Soil Health Institute, n.d; FAO, 2021). The year 2015 was proclaimed the International Year of Soils by the United Nations to raise awareness about the importance of soil health. Member states were encouraged to craft policies, programs, and initiatives to guarantee sustainable soil management (FAO, 2015). Likewise, several scientific studies have highlighted the urgency to address soil degradation. There is a substantial correlation between soil health, climate change, food security, and ecosystem services; therefore, the development of scientific-backed communication (Global Soil Week, n.d).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal “call to action” for poverty eradication, planetary protection, and universal peace and prosperity, appreciating the various approaches to climate action (UN, 2013). SDG 13 encapsulates broad climate change communication in addressing the global climate change crisis. Target 13.3 emphasizes raising public awareness and increasing climate education and human and institutional capacity for climate change mitigation and adaptation (WHO, 2022; UNDESA, 2022). Educating individuals, institutions, and communities about the climate change causes and impacts and promoting action to mitigate and adapt to its effects is fundamental. The SDG 13 framework moreover calls for increased public participation and engagement in climate change policymaking and action (UNDP, 2021).

Climate news coverage prompted the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and intensified global scientific research on greenhouse gas emissions. However, despite the media’s milestone achievement inspiring the formation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), traditional media participation in climate change issues rarely focuses on soil health-related mitigation. Journalists and traditional media outlets are generally considered more reliable than other media sources due to their adherence to journalistic standards, access to diverse sources, commitment, audience reach and track record of accurate and objective reporting (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2014; Pew Research Center, 2018; Vraga & Tully, 2020). The traditional media’s commitment to fact-checking and presenting reliable information sets it apart from social media, where misinformation can be rampant (Fletcher & Nielsen, 2017). Therefore, traditional media remains a reliable, and underutilized medium for raising public awareness.

5. Media and the Social Side of Soils

Various theoretical approaches have highlighted the importance of media and communication in climate change mitigation. Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) is a framework that guides how media outlets can effectively communicate during a crisis. The theory emphasizes the importance of tailoring communications based on the specific situation and includes key factors such as crisis history, severity, and responsibility (Yin & Yang, 2020; Coombs, 2007). In this theory, accountability, transparency, and compassion are underlined as critical components of effective crisis communication, and trust is essential in situational crisis communication (Kim & Kim, 2019). Public trust boosts confidence toward successful policy implementation and behaviour change, leaning toward sustainable practices in climate change. Several studies support integrating frameworks like the SCCT to guide communication strategies that build public trust and encourage engagement toward sustainable agricultural practices (Böhm et al., 2019; Kim & Kim, 2019; Yin & Yang, 2020). Kreps and Bosley (2020) emphasize that applying SCCT could have effectively communicated COVID-19 protocols and vaccination during the pandemic, ensuring trust, accuracy, consistency, empathy, and behaviour change among the public.

Of particular interest to the authors of this paper is the media’s role in behavioural and social change action-oriented processes such as building up supportive networks, and farmers interacting with other farmers, which can strengthen farmers’ adaptive capacity to understand and respond to challenges such as resource degradation and climate change. Farmers’ adaptive capacity refers to their perceptions and capabilities as individuals or groups to adapt to change and develop or use innovations that respond to existing or future stress (Klerkx et al., 2010; Pigford et al., 2018; Sartas et al., 2018). There is extensive literature that explains that farmers are social actors who have the potential to transform their immediate environment with individual decision-making and change systems through collective action, often using communication with other stakeholders and engaging in learning that fuels innovation (Leeuwis 2004; Van Poeck, et al. 2017). We refer to this simply as the “social side of soils” and seek evidence (or the lack thereof) of how media features and facilitates farmers’ individual and collective capacity to adapt and participate in groups or organizations, and networks, while effectively communicating within the context of the soil health and climate crisis.

Figure 1 envisions the social side of soils with the media’s involvement in an ideal application of the SCCT:

Further study is needed to understand media constraints and biases regarding climate change coverage. One apparent challenge in Canada is that the oil and gas industry heavily influences climate change media coverage because of the significant impact of this sector on the country’s economy and emissions (Stoddart et al., 2017). As a result, this attention often overshadows other important climate change-related topics, such as soil health, farmer management practices and land users’ crucial role in mitigating climate change. A study by Cahill et al. (2010), however, has found that several media outlets, including the Mail and Globe, National Post, New York Times, Associated Press, and the Kitchener-Waterloo Record, have influenced perspectives on promoting organic agriculture and consumer choices in North America. There are potential opportunities, but media coverage of climate change issues is sometimes misled by political and ideological viewpoints, with conservative outlets attempting to downplay climate change existence and mitigation (Jamieson & Hardy, 2014). Historically, Canada’s news media is overshadowed by the United States media industry (Goodrum, 2021). In its global position as a socio-political powerhouse, there are still huge debates and equally popular opinions in the United States as to whether climate change exists, euphemizing the need to mitigate it (Harris, 2000). This delays policy decisions and deflects public attention from the urgency of addressing the crisis (Cook et al., 2016).

6. Materials and Methods

Our methodology seeks to examine the role of the media in enabling climate action in the Canadian agricultural sector with a focus on soil management practices. Within the past five years, the “social side of soils” has garnered the attention of several researchers, particularly in Ontario, Canada with the implementation of policies such as New Horizons (2018), Ontario’s Agricultural Soil Health and Conservation Strategy (Allen, 2021; Arseneau, 2022). This is an emerging area of research that has been relatively understudied, but it has linked social processes to the adoption of cover crops, no-till practices, and crop rotation and the increase in farmers’ and other stakeholders’ awareness about the benefits of soil health and conservation practice (Arbuckle and Roesch-McNally; 2015, Liang et al., 2020).

Qualitative studies that use document analysis and methods such as interviews and observation contribute to understanding individual behaviour, collective action, and the influence of organizations and learning processes in rural and agricultural change contexts (Wauters & Mathijs, 2014; Cliffe, 2016). Important findings from multiple qualitative exploratory-descriptive studies conducted within a similar time frame combine as a meta-study and are useful for identifying common themes across studies that generate contributions to advance the current body of knowledge on a particular subject (Shaw, 1999; Hannes & Macaitis, 2012). One of the themes identified in recent soil health studies involving in-depth interviews with farmers has been the importance of their information access, knowledge sharing and reaction to soil-related climate change mitigation strategies (Allen, 2021).

One of the areas not yet studied in Canada within the “social side of soils” is the media coverage of soil health and climate change. Therefore, a study was designed to “determine how the media sources and reports soil health-related climate change mitigation information” (Mundenga, 2023:6). Two methods were used: media content analysis and a journalist survey.

7. Content Analysis of Media Articles

The search terms included for data collection: “soil health” and “climate change mitigation” were used to investigate the coverage of soil health-related climate change mitigation. Through MCA, the researchers searched for content from specific news collection databases (Factiva, ProQuest and Gale Academic OneFile). The content analysis captured the first 100 news articles on soil health linked to climate change mitigation in Canada that came up in the results. The media articles were obtained from online newspapers, dated between the 1st of January 2022 and the 1st of January 2024. A hundred news articles allow for a representative and diverse range of sources and viewpoints. It provides a substantial dataset for analysis, enabling the researcher to identify the media framing of the topic. The process involved screening by title, abstract, and full text for relevance to the study. Second, the articles that met the inclusion criteria were coded based on their content to determine the media perception and representation of soil health-related climate change mitigation.

8. Journalist Survey

The participants were media professionals (journalists) identified through publicly available lists of media contacts who were invited to participate in an online survey. The researchers searched on Google for “Canadian press contacts” to generate lists or directories of journalists and media outlets. The other option was to check out websites of media outlets for a section for press inquiries or use media monitoring tools like Muck Rack to search for climate or agricultural journalists’ contact details by beat, industry, or location. Approximately 150 contacts in Canada were identified, with 31 purposively selected to participate in the online survey.

9. Results

As

Table 1 summarizes, a total of 126 newspaper references were extracted from three databases. In the process, 26 references were identified and automatically removed by Covidence as duplicates. Only 100 news articles could go through the manual screening process, resulting in 23 relevant to the topic under investigation. At the same time, 51 more studies were removed for being outright irrelevant, wrong location, or outside the study criteria. There were instances where news articles were excluded from the study for discussing climate change mitigation methods, without mention of soil. Other articles were found incompatible due to confusing soil fertility with soil health. Therefore, only 23 news articles qualified as media reports on soil health-related climate change mitigation in Canada between January 1

st, 2022, and January 1

st, 2024. The themes covered in the 23 articles mainly included the link between implementing soil health practices and addressing the climate crisis. These practices comprise cover cropping, crop diversity, minimal soil disturbance, maintaining living roots and increasing soil organic matter (SOM).

10. Survey Findings

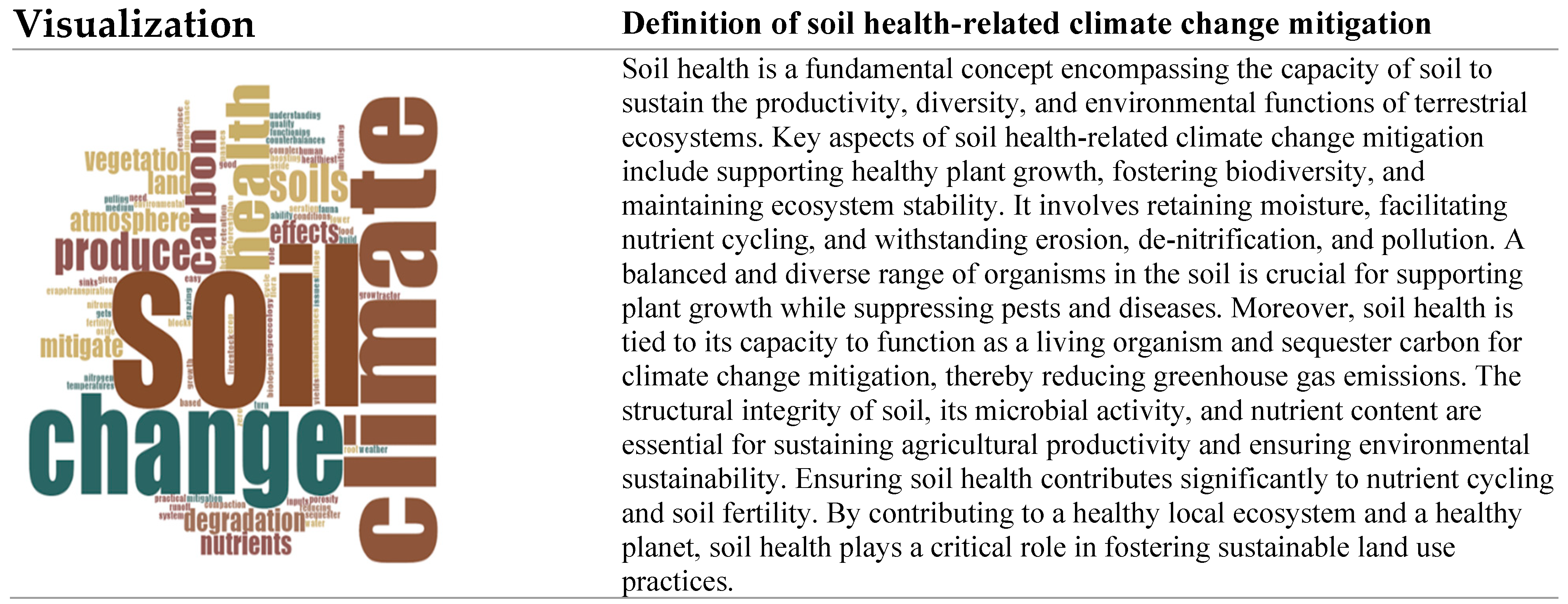

The online surveys with journalists indicated a wide understanding among journalists that soil health is relevant to climate change mitigation. Based on the participants’ data on perceptions, attitudes, and media inferences on “soil health-related climate change mitigation,” a visualization based on keywords and cues was generated from one of the survey questions inquiring about the participants’ comprehension of the term. Keywords from different responses were integrated into a word cloud to create a broad understanding of the term. An explanation is also given to contextualize the responses.

Figure 1 summarizes the thematic grouping of information from the coding of the survey responses.

Figure 2.

Media’s Framing of Soil Health.

Figure 2.

Media’s Framing of Soil Health.

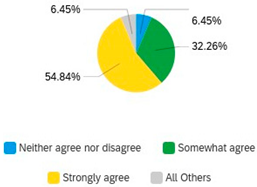

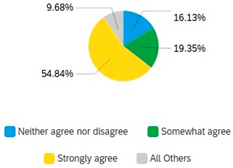

The research discovered that a significant majority of participants, specifically 76% strongly or somewhat agreed that soil health is crucial in mitigating climate change. Similarly, 87% of the participants strongly or somewhat agreed that the media holds significant importance as a stakeholder in climate change communication. However, only 58% of the participants believe the media does not adequately fulfill its role as a forum for climate change communication. This happens despite journalists having a moral obligation to engage, inform, and support the farming community about the impact of soils on climate change mitigation.

Table 2.

Media’s Perception of Soil Health Communication.

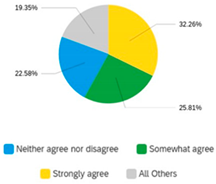

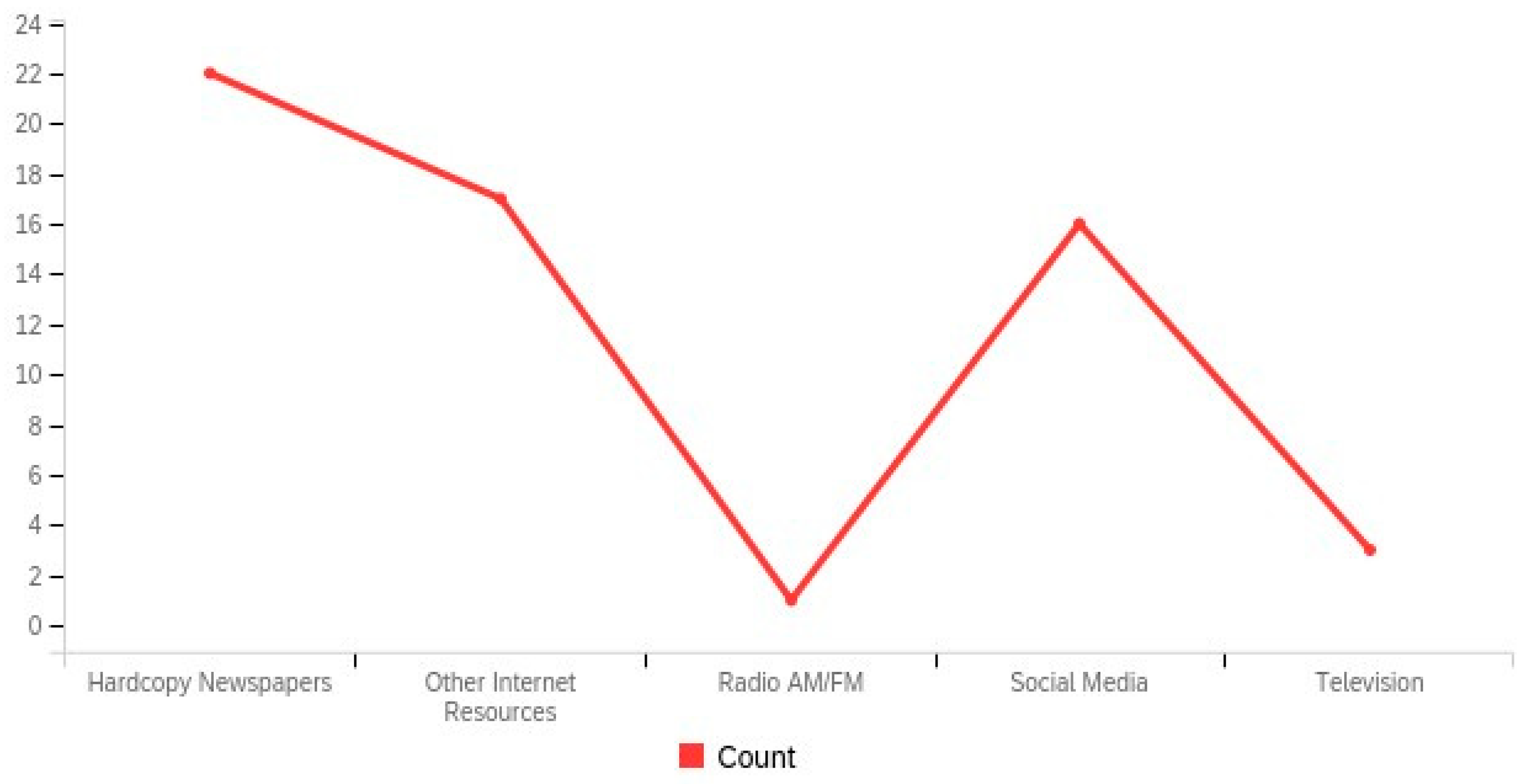

Regarding media consumption habits and perceptions of credibility and preferences regarding soil health-related climate change content, the study determined that 27% of the participants believe that their audience relies on social media, while 37% turn to traditional hardcopy newspapers. Additionally, 2% of farmers depend on FM/AM radio, 5% on television, and 29% utilize other online resources.

Figure 3.

Media preferences.

Figure 3.

Media preferences.

The survey established that online sources of information account for about 29% of soil health communication. These resources consist of blog entries, podcasts, producer organization websites, and periodic newsletters.

The findings identified several challenges faced by the media when covering soil health-related climate change mitigation. Media outlets listed funding, staff, and/or time constraints, making it challenging to dedicate resources to niche topics such as soil health, hence the neglect of soil health coverage in relation to wider reports on climate change mitigation in Canada. Even better-resourced media outlets often prioritize topics with broader appeal, leading to limited soil health-related climate change mitigation coverage. A lack of trust or miscommunication between soil or climate scientists and journalists was mentioned as hindering the accurate and effective reporting of soil health-related climate change mitigation. Moreover, soil health was mentioned as a complex scientific subject requiring careful communication to make it consumable to a general audience. This is coupled with the fact that the public has limited awareness of the topic, making it harder for media outlets to engage their audience There is also a sheer absence of coordination efforts between media outlets, scientists, and organizations leading to inconsistent coverage.

11. Final Discussion and Conclusion

Findings from media content analysis and journalist surveys suggested that the media in Canada has recently covered soil health-related climate change mitigation during soil workshops, conferences, and international negotiations, where journalists can meet and interview soil and climate scientists, but this coverage is limited. Outside of these specialized events, soil health-related climate change mitigation is not “a beat” that media outlets actively pursue or have the resources to engage. In some cases, media outlets send journalists with a general knowledge of climate change but lack specialization in soil’s role in mitigating climate change. In the wider media studies literature, these are called “parachute journalists” and they are unlikely to repeat their coverage of a particular story (Okigbo & Eribo, 2004).

The reliance on climate crisis-driven coverage is apparent in the media identified in this study. To some extent, it can be argued that soil health has not yet been perceived by the Canadian public as a crisis issue. Both traditional and Internet-based media need to get behind platforms that are important for stakeholders to exchange knowledge on soil-related climate change issues and address the need for effective communication in likely future crisis situations. Knowing and understanding resource-related challenges within media may help to help media outlets play a role in building trust and credibility in soil health and climate change coverage hence improving the integration of communication strategy within policies where it is currently absent. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Soil Conservation Council of Canada (SCCC), and the provincial and territorial governments need to prioritize media engagement as part of their soil health communication strategy, given the context of climate change as a global crisis. While Ontario’s Agricultural Soil Health and Conservation Strategy embraces various multimedia instruments as communication tools, it is also imperative to note that the Federal Government’s National Soil Health Strategy is silent on media involvement. Supporting effective climate change reporting in the media through a raft of policy measures is essential such as funding incentives, training programs, and collaborations with media organizations. Efforts should be made to bridge the gap between policymakers and journalists to ensure accurate and timely reporting on climate change issues. Policymakers can provide journalists access to experts and scientific information to facilitate effective communication.

The media is a critical stakeholder in climate action. Well-resourced media outlets like the CBC, Global News, Bloomberg Canada and CTV should strive to lead soil health-related climate change mitigation reporting. They have the means to avoid parachute journalism and ensure accurate reporting contributing to more informed and effective coverage. Reporting on a specialized niche like soil health-related climate change mitigation requires collaboration with land users such as farmers and scientists to build trust and communication channels between journalists, farmers and scientists to stay updated on the latest research and developments. More coverage of soil health by the media contributes to raising awareness among the farmers, and then more widely within society, including the consumers and the electorate leading to increased policy support and action toward sustainable agricultural practices. Journalists and communications specialists should engage with farmers to seek compelling human-interest stories and success stories related to soil health and climate change mitigation. Media professionals in Canada can play a much stronger role in engaging and inspiring their audiences to act by highlighting the positive impact of sustainable farming practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize support from the National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) CREATE Climate Smart Soils Program and its Principal Investigator, Professor Claudia Wagner-Riddle and Project Manager, Jordan Minigan. We acknowledge the advice received during this study from Dr. Ricardo Ramirez.

References

- Alberta Environment. (2007). Albertans & climate change facts about climate change. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/albertansclimate00albe_5/mode/2up.

- Allen, P. 2021. The social side of soils: a farmer centred analysis of adoption of cover crops. MSc thesis, Guelph, ON: University of Guelph. Retrieved from https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/items/537572f6-889b-499c-8f64-aae583255db9.

- Arbuckle, J. G., & Roesch-McNally, G. (2015). Cover crop adoption in Iowa: The role of perceived practice characteristics. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 70(6), 418–429. [CrossRef]

- Archer, D. & Rahmstorf, S. (2009). The Climate Crisis: An Introductory Guide to Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Arseneau, M. 2022. The role of soils training programs in on-farm adoption of climate-smart soils practices. Msc thesis, Guelph, ON: University of Guelph. Retrieved from https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/items/494261f2-51a6-4f4a-9a47-2ca469a1491c.

- Bethge, S., Cornish, L., & Rickwood, P. (2018). Journalism and the human-nature relationship: Charting the stories we live by. Environmental Communication, 12(7), 1021-1036.

- Blackstock, K. L., Kelly, G. J., & Horsey, B. L. (2010). Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecological economics, 69(5), 931-942.

- Blanco-Canqui, H., & Lal, R. (2009). Crop Residue Removal Impacts on Soil Productivity and Environmental Quality. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 28(3), 139–163. [CrossRef]

- Böhm, G., Pfister, G., & Schwarte, L. (2019). Communicating climate change–An extension of situational crisis communication theory to climate change communication. International Journal of Communication, 13, 21.

- Bontempo, L., Crupi, A., Massetti, E., & Nucera, R. (2021). The role of the media in climate change communication: An overview of the literature. Climate, 9(2), 24.

- Bouma, J. (2022). How about the role of farmers and of pragmatic approaches when aiming for sustainable development by 2030? European Journal of Soil Science, 73(1). [CrossRef]

- Busungu, C., Gongwe A., Naila, D. L., Munema, L., (2019) Complementing extension officers in technology transfer and extension services: understanding the influence of media as change agents in modern agriculture. International Journal of Research – Grantalaayah. Vol 7 (6) pp 248 – 269. [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S., Morley, K., & Powell, D. A. (2010). Coverage of organic agriculture in North American newspapers: Media: linking food safety, the environment, human health and organic agriculture. British Food Journal (1966), 112(6-7), 710–722. [CrossRef]

- Chahal, I., Hooker, D. C., Deen, B., Janovicek, K., & Van Eerd, L. L. (2021). Long-term effects of crop rotation, tillage, and fertilizer nitrogen on soil health indicators and crop productivity in a temperate climate. Soil & Tillage Research, 213, 105121-. [CrossRef]

- Cliffe, N., Stone, R., Coutts, J., Reardon-Smith, K., & Mushtaq, S. (2016). Developing the capacity of farmers to understand and apply seasonal climate forecasts through collaborative learning processes. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 22(4), 311–325. [CrossRef]

- Congreves, K.A., Hooker, D.C., Hayes, A., Verhallen, E.A., Van Eerd, L.L. (2017). Interaction of long-term nitrogen fertilizer application, crop rotation, and tillage system on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics. Plant Soil 410(2017): 113-127.

- Cook, J., Nuccitelli, D., Green, S.A., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting, R., … Ratner, K. (2016). "Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature," Environmental Research Letters, 11, 04802.

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting Organization Reputations During a Crisis: The Development and Application of Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. [CrossRef]

- de Boon, A., Sandstrӧm, C., and Rose, D.C. (2022). Governing agricultural innovation: A comprehensive framework to underpin sustainable transitions. Journal of Rural Studies (2022): 407-422. [CrossRef]

- Dupar, M. T., Swim, J. K., Meldrum, L. R., Ozawa, C. P., & Williamson, A. L. (2016). Communicating climate change: A practitioner’s guide. Springer.

- Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Are legacy media taking cues from social media? Social media use and news consumption among Flemish journalists. Journalism, 18(2), 137-154. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2015). Status of the World’s Soil Resources, International Year of Soils 2015. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/soils-2015/en/.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2021). Global Soil Partnership. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/en/.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., Jung, N., & Valenzuela, S. (2014). Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 461-476. [CrossRef]

- Global Soil Week. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved from https://globalsoilweek.org/about-us/.

- Goodrum, A. (2021). Elections, Wars, and Protests? A Longitudinal Look at Foreign News on Canadian Television. Canadian Journal of Communication, 36(3), 455–476. [CrossRef]

- Hannes, K., & Macaitis, K. (2012). A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis: update on a review of published papers. Qualitative Research: QR, 12(4), 402–442. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A. (1994). The mass media and environmental issues. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

- Harris, P. G. (2000). Climate change and American foreign policy. St. Martin’s Press.

- Harrison, C.M., Burgess, J., Clark, J., (1998). Discounted knowledges: farmers’ and residents’ understandings of nature conservation goals and policies. Journal of Environmental Management 54: 305–320.

- Hou, D. (2022). Expediting climate-smart soils management. Soil Use and Management, 38(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2019). IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/home/.

- Jamieson, K. H., & Hardy, B. W. (2014). Leveraging scientific credibility about Arctic Sea ice trends in a polarized political environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS, 111(Supplement 4), 13598–13605. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2019). Underlying processes of SCCT: Mediating roles of preventability, blame, and trust. Public Relations Review, 45(3), 101775-. [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L., N. Aarts, and C. Leeuwis. 2010. Adaptive Management in Agricultural Innovation Systems: The Interactions Between Innovation Networks and Their Environment. Agricultural Systems 103: 390–400.

- Kreps, G. L., & Bosley, J. C. (2020). Coronavirus communication during a crisis: Applying the principles of effective risk communication. mHealth, 6, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. (2020). Soil organic matter and water retention. Agronomy Journal, 112(5), 3265–3277. [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, C. (2004). Communication for rural innovation rethinking agricultural extension. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science.

- Lehman, R. M., Cambardella, C.A., Stott, D.E., Acosta-Martinez, V, Manter, D.K., Buyer, J.S., Maul, J.E., Smith, J.L., Collins, H.P., Jalvorson, J.J., Kremer, R.J., Lundgren, J.G., Ducey, T.F., Jin, V.L., and Karlen, D.L. (2015). Understanding and enhancing soil biological health: The solution for reversing soil degradation. Sustainability. 7:988-1027. [CrossRef]

- Liang, B. C., VandenBygaart, A. J., MacDonald, J. D., Cerkowniak, D., McConkey, B. G., Desjardins, R. L., & Angers, D. A. (2020). Revisiting no-till’s impact on soil organic carbon storage in Canada. Soil & Tillage Research, 198, 104529-. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.B., Burton, D.L., Heung, B., Lynch, D.H. (2021). Influence of cropping system and soil type on soil health. Canadian Journal of Soil Science. 101(4): 626-640. [CrossRef]

- Masud, M. M., Akhatr, R., Nasrin, S., & Adamu, I. M. (2017). Impact of socio-demographic factors on the mitigating actions for climate change: a path analysis with mediating effects of attitudinal variables. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 24(34), 26462–26477. [CrossRef]

- McCorkle, C.M., (1989). Towards a knowledge of local knowledge and its importance for agricultural R&D. Agriculture and Human Values 6 (3), 4–12.

- Milfont, T. L., Thompson, C. E., Raczek, A. E., Louise Strack, L., Weeden, D. H., Pazhayamadom, D. G., ... & Ristenpart, W. D. (2020). Designing and evaluating interventions to promote pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic review. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(2), 217-238. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. (1998). Promotional strategies and media power. In Briggs, A., & Cobley, P. (Eds) (1998). The media: an introduction. A. W. Longman, pp, 60–65.

- Mundenga, T. (2023). Examining media as a stakeholder in soil health-related climate change mitigation, Guelph, ON, University of Guelph. Retrieved from: https://hdl.handle.net/10214/27873.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (n.d.). Global climate change: Vital signs of the planet. Retrieved from https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/.

- National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. (2021). Climate Variability. Retrieved from https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-variability.

- Okoliko, D. A. & de Wit, M. P. (2020). Media(ted) Climate Change in Africa and Public Engagement: A Systematic Review of Relevant Literature. African Journalism Studies, 41(1), 65–83. [CrossRef]

- Okigbo, Charles., & Eribo, F. (2004). Development and communication in Africa. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Palmer, T. (2019). Climate Variability and Change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. [CrossRef]

- Parks, P. (2020). Is Climate Change a Crisis - And Who Says So? An Analysis of Climate Characterization in Major U.S. News Media. Environmental Communication, 14(1), 82–96. [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. (2018). Trust and distrust in America. Retrieved from https://www.people-press.org/2018/07/19/trust-and-distrust-in-america/.

- Pigford, A.A.E., Hickey, G.M., Klerkx. L. (2018). Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions. Agricultural Systems. 164:116-121. [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, M. (2015). Climate. In the Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/climate.

- Sartas, M., Schut, M. Hermans, F., van Asten P., Leeuwis, C. (2018). Effects of multi-stakeholder platforms on multi-stakeholder innovation networks: Implications for research for development interventions targeting innovations at scale. PloS one. 13 (6), e0197993–e0197993.

- Schäfer, S., Ivanova, A., & Schmidt, A. (2014). What drives media attention to climate change? Explaining issue attention in Australian, German, and Indian print media from 1996 to 2010. The International Communication Gazette, 76(2), 152–176. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A., Ivanova, A., & Schäfer, M. S. (2013). Media attention for climate change around the world: A comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1233–1248. [CrossRef]

- Soil Health Institute. (n.d.). Soil health communication. Retrieved from https://soilhealthinstitute.org/soil-health/communication/.

- Stoddart, M. C. J., Tindall, D. B., Smith, J., & Haluza-Delay, R. (2017). Media Access and Political Efficacy in the Eco-politics of Climate Change: Canadian National News and Mediated Policy Networks. Environmental Communication, 11(3), 386–400. [CrossRef]

- Swain, K. A. (2014). Mass Media Roles in Climate Change Mitigation. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation (pp. 161–195). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Time to treat the climate and nature crisis as one indivisible global health emergency. (2023). Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 103(4), i–iii. [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, C. (1996). Constructing climate change: claims and frames in US news coverage of an environmental issue. Public Understanding of Science (Bristol, England), 5(3), 269–283. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (n.d) Climate Action. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26.

- United Nations. (2013). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2021). Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html.

- Ussiri, D., & Lal, R. (2013). Soil Emission of Nitrous Oxide and its Mitigation (1st ed. 2013.). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F., Lawrence, G., (1994). Farmer rationality and the adoption of environmentally sound practices; a critique of the assumptions of traditional agricultural extension. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 1 (1), http://library.wur.nl/ejae/v1n1t.html, June 2004.

- Van Poeck, K., Læssøe, J., and Block, T. (2017). An exploration of sustainability change agents as facilitators of nonformal learning: mapping a moving and intertwined landscape. Ecology and Society. 22(2):33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26270111.

- Vraga, E. K., & Tully, M. (2020). New media, old biases: Differences in the portrayal of the news across platforms and devices. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(1), 26-47. [CrossRef]

- Wauters, E. & Mathijs, E. (2014) The adoption of farm level soil conservation practices in developed countries: a meta-analytic review. International journal of agricultural resources, governance and ecology 10 (1), 78–102. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., & Yang, X. (2020). Exploring the dynamics of communication patterns in climate change discourse: Evidence from China and the United States. Journal of Environmental Management, 254, 109786.

- Zhang, C., Hu, Y., Liu, Y., Blair, G. J., & Feng, G. (2019). From soil degradation to soil health: An integrative analysis of soil health indicators and assessment frameworks. Science of the Total Environment, 663, 82-93. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).