Submitted:

01 March 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Land Information Systems: A theoretical Perspective

2.1. The Concept and Perspective of Land Information System

2.2. Land Information System Assessment Models

2.2.1. Assessment Model Developed by The United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM)

2.2.2. Assessment Model by The World Bank

2.2.3. Assessment Indicators by Land Equity International (LEI)

2.2.4. Assessment Framework by dr Steudler

2.2.5. The Elements Considered for Assessing the Effectiveness of Land Information Systems

- Governance and People

- Operational Environment

- Sustainability Measures

2.3. The Assessment Framework for LIS in Ghana

3. Land Tenure and Land Administration in Ghana

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Results

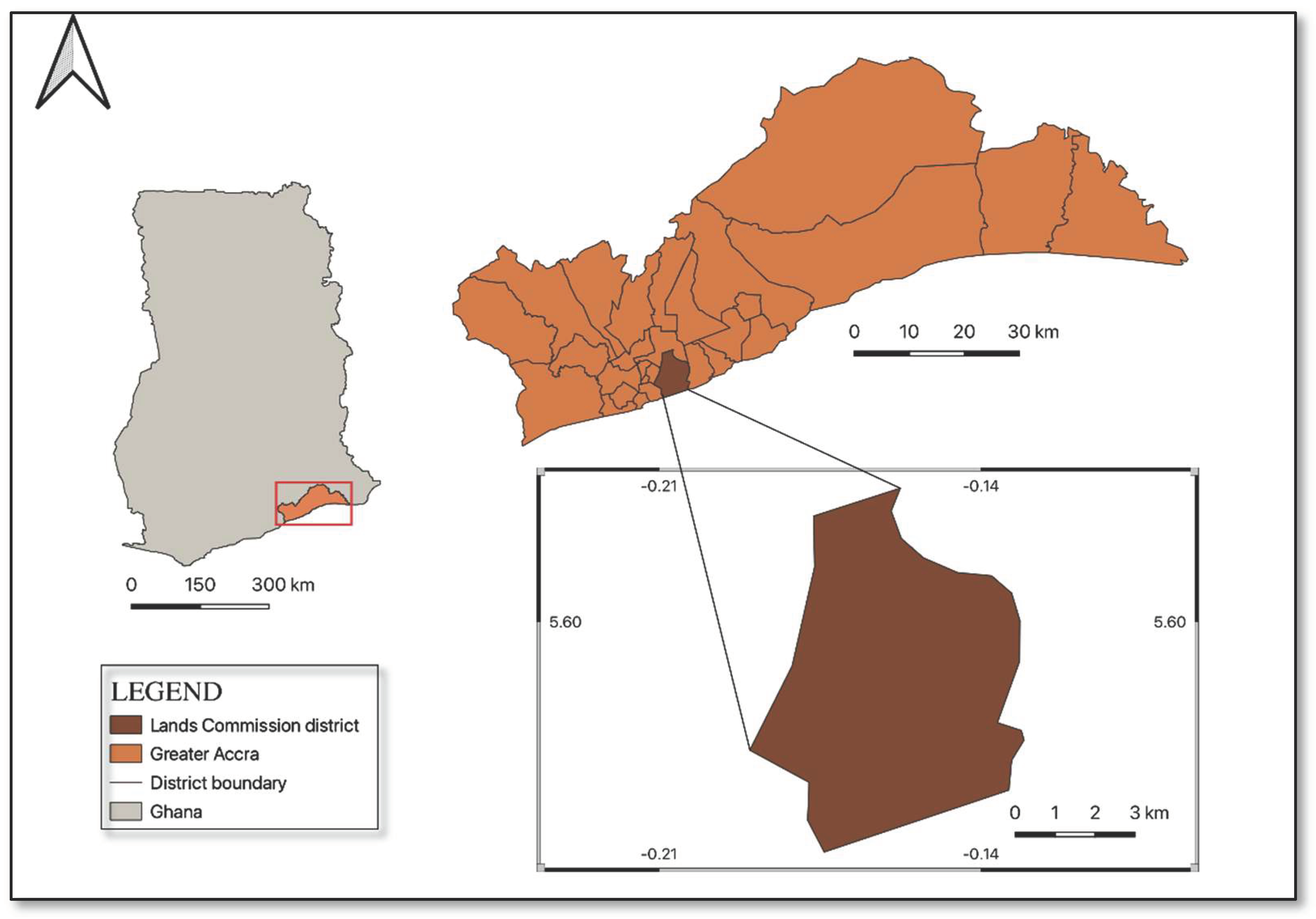

5.1. Land Administration Processes in Accra LC

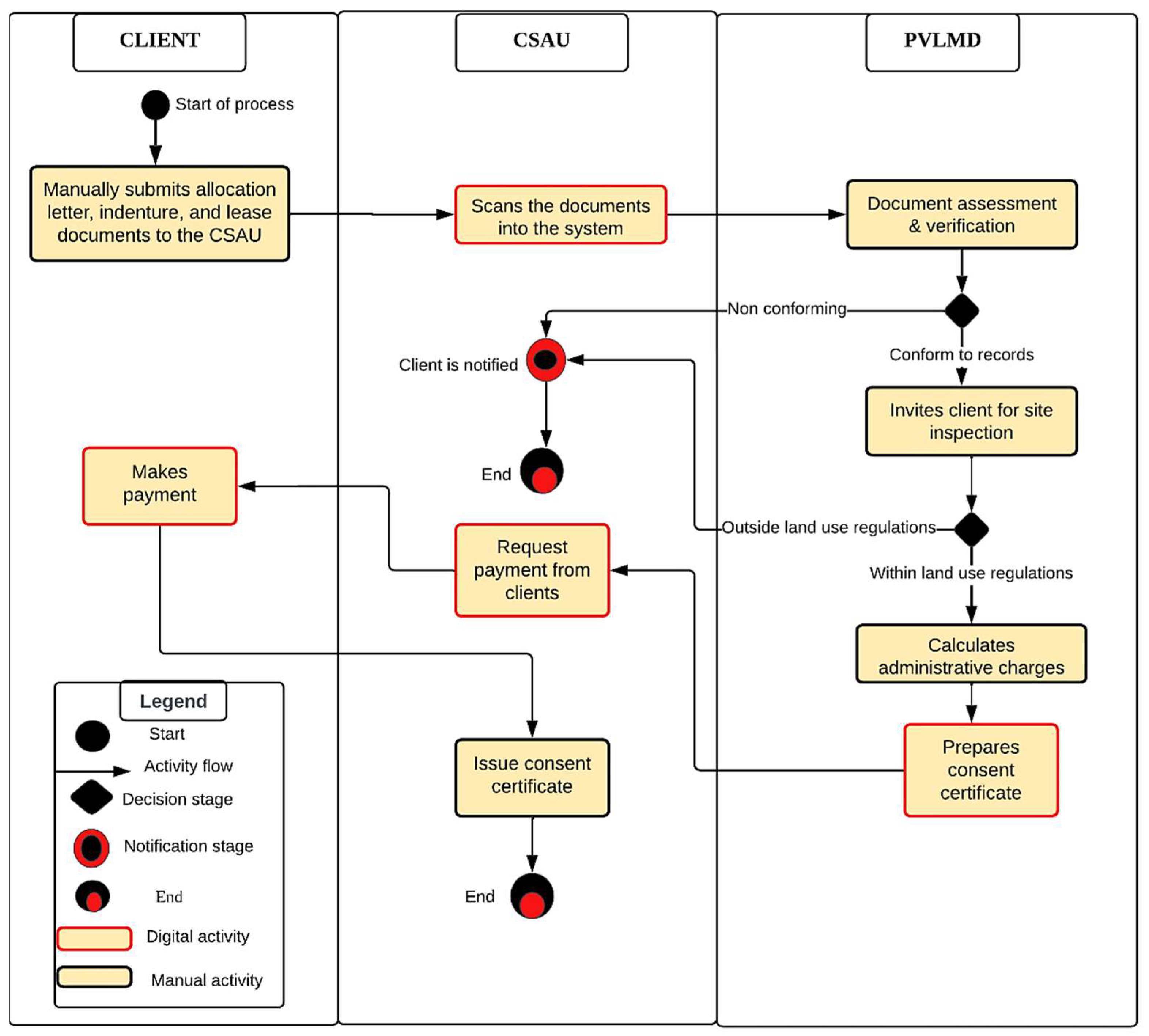

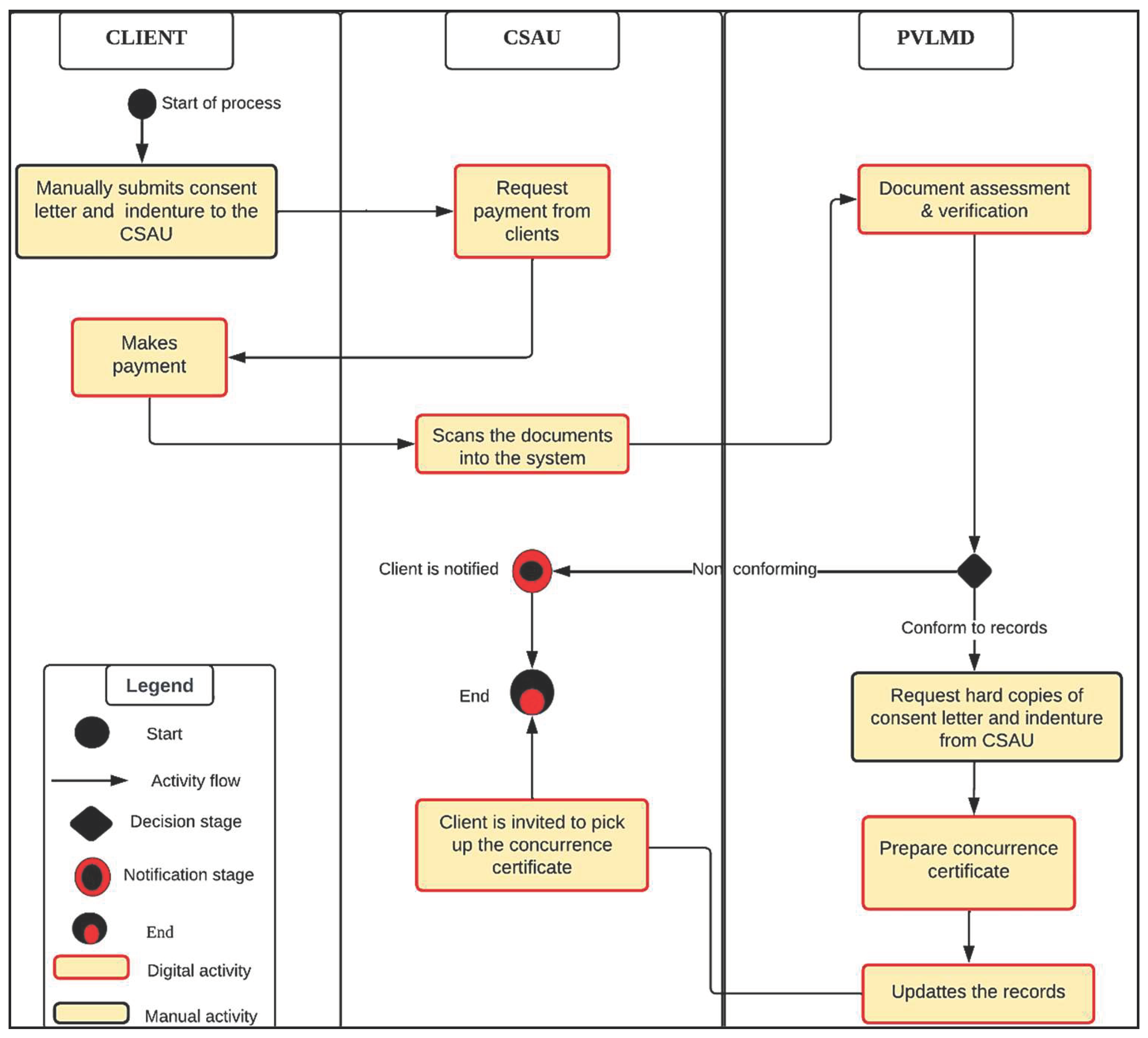

5.1.1. Processes of Public and Vested Land Management (PVLMD)

5.1.2. Processes of Survey and Mapping Division (SMD)

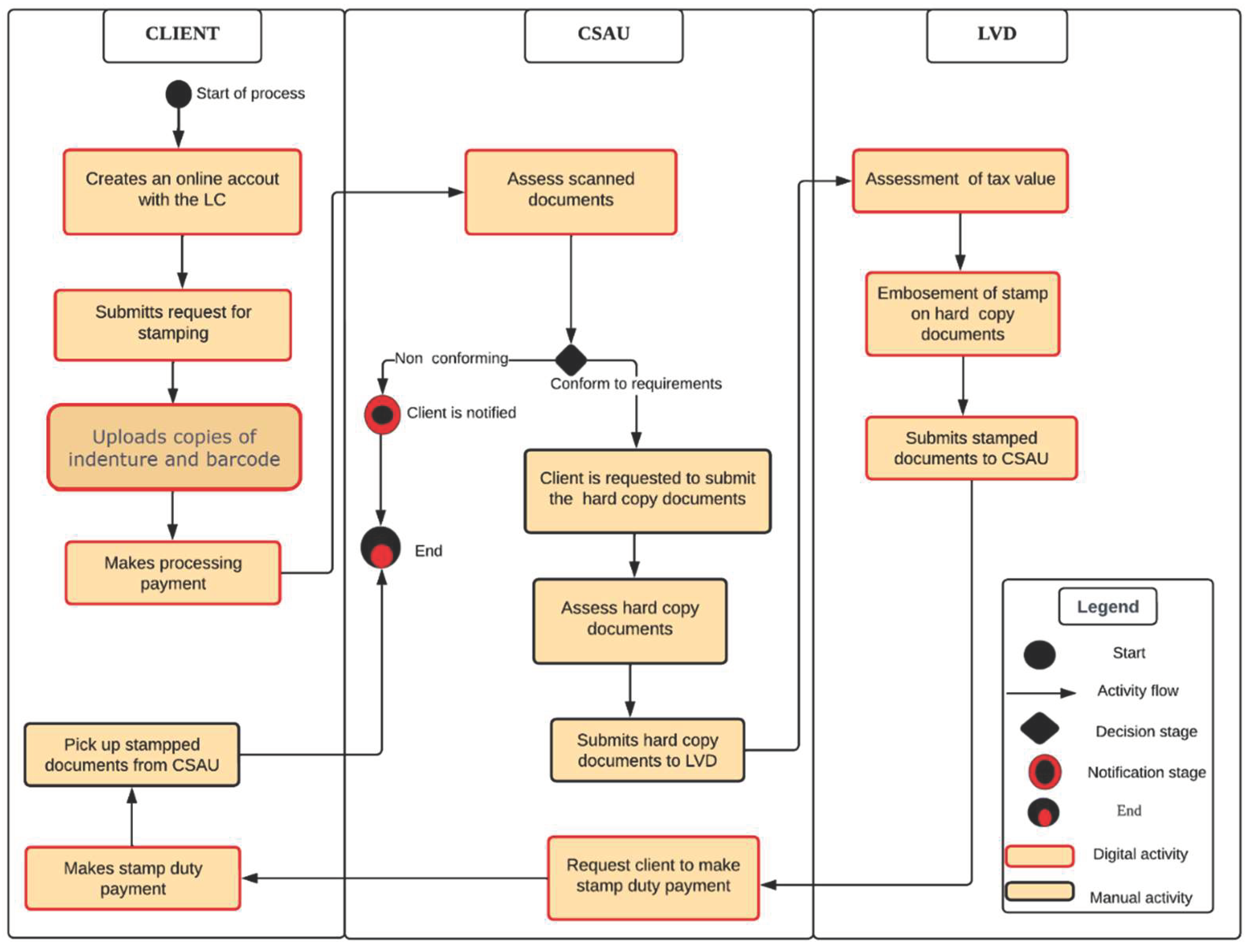

5.1.3. Processes of Land Valuation Division (LVD)

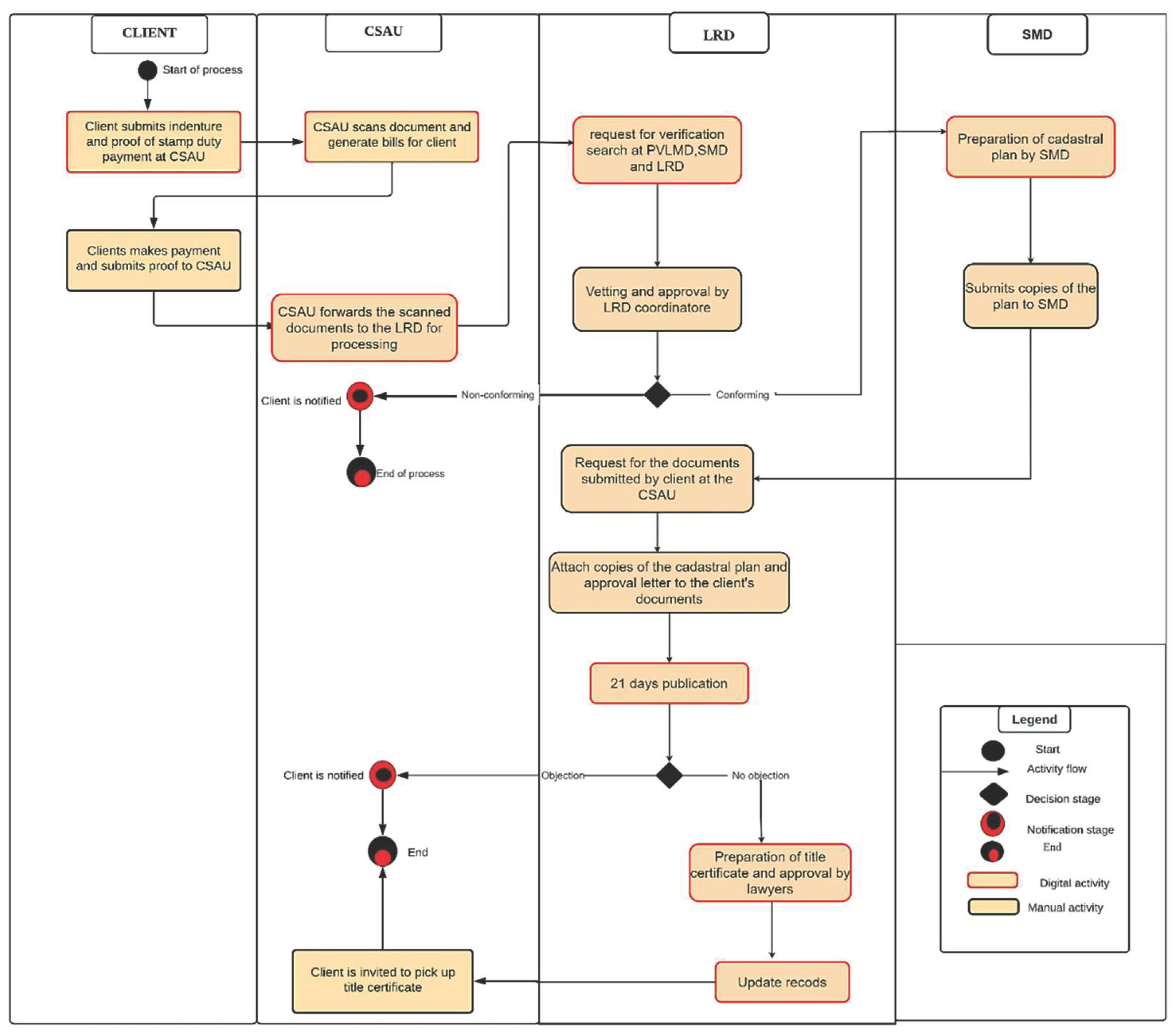

5.1.4. Processes of Land Registration Division (LRD).

5.2. Governance and People

5.3. Operational Environment

5.4. Strategies for Sustainability

6. Assessment of the LIS in Accra

6.1. Organisational, Policy, and Legal Frameworks

6.2. Technology

6.3. Data

6.4. Working Environment

6.5. Capacity and Training

6.6. ICT Strategy

6.7. Communication Strategy

6.8. Summary of LIS Assessment in Accra

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| THEME | FELA | LGAF | LEI | STAUDLER | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and people |

|

|

|

|||

| Sustainability |

|

|

|

|

||

| Operational environment |

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||

| Others |

|

|

||||

References

- “Land Administration in the UNECE Region: Development Trends and Main Principles | UNECE.” Accessed: Sep. 30, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://unece.org/housing-and-land-management/publications/land-administration-unece-region-development-trends-and.

- S. Enemark, “Land Management and Development,” Brussels, 2005.

- J. R. Quintero, “Land Information System,” N. J. Smelser and P. B. B. T.-I. E. of the S. & B. S. Baltes, Eds., Oxford: Pergamon, 2004, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- A. Meijer, “Understanding modern transparency,” International Review of Administrative Sciences, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 255–269, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kadaster International, “About Kadaster international - Kadaster.com.” Accessed: Sep. 18, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.kadaster.com/about-us.

- Z. A. Berisso and W. T. de Vries, “Exploring characteristics of GIS Adoption Decisions and Type of Induced Changes in Developing Countries: The Case of Ethiopia,” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. X. Correia, A. B. Moore, and D. P. Goodwin, “Accessibility of land data and information integration in recently-independent countries: Timor-Leste case study,” Papers in Regional Science, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 203–225, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Karikari, J. Stillwell, and S. Carver, “Land administration and GIS: The case of Ghana,” Progress in Development Studies, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 223–242, 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Biraro, “Land Information Updating: Assessment and Options for Rwanda,” University of Twente, 2014.

- D. N. Siriba and S. Dalyot, “Adoption of volunteered geographic information into the formal land administration system in Kenya,” Land use policy, vol. 63, pp. 279–287, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Yaw Adiaba, “A Framework for Land Information Management in Ghana,” University of Wolverhampton, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://wlv.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/2436/332138/THESIS 0920118 doc.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- P. F. Dale and J. D. McLaughlin, Land Administration. UK: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0895796705000530.

- G. Larsson, Land registration and cadastral systems : Tools for Land Information and Management. New York, USA: Longman Scientific & Technical, 1991. Accessed: Jan. 18, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://archive.org/details/landregistration0000lars/page/n9/mode/2up.

- UNECE, “Land Administration Guidelines,” New York and Geneva, 1996. [Online]. Available: http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/hlm/documents/Publications/land.administration.guidelines.e.pdf.

- D. Bishop et al., “Spatial data infrastructures for cities in developing countries,” Cities, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 85–96, Apr. 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. Hull and J. Whittal, “Good e-Governance and Cadastral Innovation: In Pursuit of a Definition of e-Cadastral Systems,” South African Journal of Geomatics, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 342-357–357, 2013.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. OECD, 2008.

- P. D. Ameyaw and W. T. de Vries, “Transparency of Land Administration and the Role of Blockchain Technology, a Four-Dimensional Framework Analysis from the Ghanaian Land Perspective,” Land (Basel), vol. 9, no. 491, pp. 1–25, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Ameyaw and W. de Vries, “Toward Smart Land Management: Land Acquisition and the Associated Challenges in Ghana. A Look into a Blockchain Digital Land Registry for Prospects,” Land (Basel), vol. 10, no. 3, p. 239, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Dhakal, “Can we get better information by any alternative to conventional statistical approaches for analysing land allocation decision problems? A case study on lowland rice varieties,” Land use policy, vol. 54, pp. 522–533, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Hale, “How Information Matters: Networks and Public Policy Innovation,” Georgetown University Press. Accessed: May 24, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.nl/books?hl=en&lr=&id=5z9KBUVk3yUC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&ots=5n8ptL7ekW&sig=hw1VveKb1EW5mNs57zRO2NoxcL0&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- J. Kaufmann and D. Steudler, “Cadastre 2014: A Vision for a Future Cadastral System,” 1998.

- G. Romano, P. Dal Sasso, G. Trisorio Liuzzi, and F. Gentile, “Multi-criteria decision analysis for land suitability mapping in a rural area of Southern Italy,” Land use policy, vol. 48, pp. 131–143, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Ahuja and A. P. Singh, “Computerization of Land Records in West Bengal,” Man and Development, vol. 28, pp. 59–76, 2006.

- D. Steudler, “A Framework for the Evaluation of Land Administration Systems,” The University of Melbourne, 2004.

- A. Showaiter, “Assessment of a Land Administration System: a Case Study of the Survey and Land Registration Bureau in Bahrain,” University of Twente, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://webapps.itc.utwente.nl/librarywww/papers_2018/msc/la/showaiter.pdf.

- UNGGIM, “Framework for Effective Land Administration: A reference for developing, reforming, renewing, strengthening, modernizing, and monitoring land administration,” 2020.

- Z. Ali, A. Tuladhar, and J. Zevenbergen, “Developing a framework for improving the quality of a deteriorated land administration system based on an exploratory case study in Pakistan,” Nordic journal of surveying and real estate research, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 30–57, 2010.

- T. Burns, “Land Administration Reform: Indicators of Success and Future,” Agriculture and Rural Development, pp. 1–244, 2007.

- S. D. Chekole, W. T. de Vries, and G. B. Shibeshi, “An Evaluation Framework for Urban Cadastral System Policy in Ethiopia,” Land (Basel), vol. 9, no. 60, pp. 1–12, 2020.

- S. Enemark and P. van der Molen, “Capacity Assessment in Land Administration,” Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008.

- K. Deininger, H. Selod, and A. Burns, “The Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practice in the Land Sector,” The World Bank, no. April 2010, p. 168, 2012.

- Land Equity International, “Land Administration Information and Transaction Systems Final State of Practice Paper,” Wollongong, 2020.

- H. Zhang and C. Tang, “A performance assessment model for cadastral survey system evaluation,” Cadastre: Geo-Information Innovations in Land Administration, pp. 33–45, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- World Bank, “Digital Government Readiness Assessment Questionnaire,” Washington, DC, 2019.

- M. Lengoiboni, C. Richter, and J. Zevenbergen, “Cross-cutting challenges to innovation in land tenure documentation,” Land use policy, vol. 85, pp. 21–32, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Biraro, J. Zevenbergen, and B. K. Alemie, “Good Practices in Updating Land Information Systems that Used Unconventional Approaches in Systematic Land Registration,” Land (Basel), vol. 10, no. 4, p. 437, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- FAO, “Voluntary Guidelines on the Governance of Tenure: At a Glance,” Rome, 2012. Accessed: Dec. 14, 2021. [Online]. Available: www.fao.org/nr/tenure.

- D. Todorovski, “Developing a ICT Strategy for the State Authority for Geodetic Works in the Republic of Macedonia Developing a ICT Strategy for the State Authority for Geodetic Works in the Republic of Macedonia,” The University of Twente, 2006.

- A. Arko-Adjei, “Adapting Land Administration to the Institutional Framework of Customary Tenure. The case of peri-urban Ghana,” University of Twente, Enschede, 2011.

- E. D. Kuusaana and N. Gerber, “Institutional synergies in customary land markets - Selected case studies of large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) in Ghana,” Land (Basel), vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 842–868, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Parliament of Ghana, Land Act. Ghana, 2020, pp. 1–214. [Online]. Available: https://ocr-aa.s3.amazonaws.com/media/public/documents/LAND_ACT2020._ACT_1036.pdf.

- O. D. Boateng, “Country Profile Of The Land Administration Domain For Ghana: With The Inclusion Title, Deed, Customary And Informal Systems Of Land Registration,” University of Twente, 2021.

- G. Deane, R. Owen, and B. Quaye, “The Ghana Enterprise Land Information System (GELIS) as a Component of National Geospatial Policy,” Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2017, pp. 1–21.

- D. Protection, Data Protection Act, 2012. Ghana: Parliament of Ghana, 2012, pp. 1–43. Accessed: May 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://nita.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Data-Protection-Act-2012-Act-843.pdf.

- Parliament of Ghana, Right to Information Act. 2019, pp. 1–44.

- Government of Ghana, Electronic Transaction Act. 2008, pp. 1–74.

- Ministry of Lands and Forestry, “National Land Policy,” Accra, Jun. 1999.

- Parliament of Ghana, Lands Commission Act. 2008, pp. 1–18. Accessed: May 31, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://landwise-production.s3.amazonaws.com/2022/03/Ghana_Lands-Commission-Bill_2008.pdf.

- N. Ihebuzor, D. O. Lawrence, and A. W. Lawrence, “Policy Coherence and Mandate Overlaps as Sources of Major Challenges in Public Sector Management in Nigeria,” International Business Research, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 68, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Abubakari, C. Z. Abubakari, C. Richter, and J. Zevenbergen, “Exploring the ‘implementation gap’ in land registration: How it happens that Ghana’s official registry contains mainly leaseholds,” Land use policy, vol. 78, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Woodman, “The Scheme of Subordinate Tenures of Land in Ghana,” Am J Comp Law, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 457–477, Jul. 1966. [CrossRef]

- I. Masser, H. Campbell, and M. Craglia, GIS Diffusion:The Adoption and Use of Geographical Information Systems in Local Government in Europe, 1st Editio. London: CRC Press, 1996. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Badurek, “Identifying barriers to GIS-based land management in Guatemala,” Dev Pract, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 248–258, 2009. [CrossRef]

- I. B. Karikari, “Ghana ’ s Land Administration Project ( LAP ) and Land Information Systems ( LIS ) Implementation : The Issues,” International of Federation of Surveyors, vol. Article of, no. February, pp. 1–19, 2006.

- Z. Zeng and C. B. Cleon, “Factors affecting the adoption of a land information system: An empirical analysis in Liberia,” Land use policy, vol. 73, pp. 353–362, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Randhawa, “Open Source Software and Libraries,” Chandigarh, 2008.

- M. Cockburn, R. Henderson, and S. Stern, “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Innovation: An Exploratory Analysis,” in The Economics of Artificial Intelligence : An Agenda, vol. Publisher, A. Agrawal, J. Gans, and A. Goldfarb, Eds., University of Chicago Press, 2019, pp. 115–146.

- M. S. Gal and D. L. Rubinfeld, “Data standardization,” New York University Law Review, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 737–770, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- OECD, Data-Driven Innovation : Big Data for Growth and Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015. Accessed: Jun. 02, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books/about/Data_Driven_Innovation_Big_Data_for_Grow.html?id=Cn-qCgAAQBAJ.

- W. M. Appau, “Land Registration Process Modelling for Complex Land Tenure System in Ghana,” University of Twente, Enschede, 2018.

- G. Adlington, “eBook: Real Estate Registration and Cadastre. Practical Lessons and Experiences,” in FIG Working Week, 2021, pp. 1–16. Accessed: May 30, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://gadlandreg.com.

- The Association of Business Executives, “Systems Analysis,” London, 2015. Accessed: Jun. 03, 2022. [Online]. Available: www.abeuk.com.

- B. J. Weiner, “A theory of organizational readiness for change,” Implementation Science, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. Clohessy, H. Treiblmaier, T. Acton, and N. Rogers, “Antecedents of blockchain adoption: An integrative framework,” Strategic Change, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 501–515, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Wang, Y. S. Wang, and Y. F. Yang, “Understanding the determinants of RFID adoption in the manufacturing industry,” Technol Forecast Soc Change, vol. 77, no. 5, pp. 803–815, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Harcenko, P. M. Harcenko, P. Dorogovs, and A. Romanovs, “IT Service Desk Implementation Solutions,” Scientific Journal of Riga Technical University. Computer Sciences, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 68–73, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshehri and S. Drew, “A Comprehensive Analysis of E-government services adoption in Saudi Arabia: Obstacles and Challenges,” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, vol. 3, no. 2, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Biitir, A. W. Miller, and C. I. Musah, “Land Administration Reforms: Institutional Design for Land Registration System in Ghana,” Journal of Land and Rural Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 7–34, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Bennett, M. Pickering, and J. Sargent, “Transformations, transitions, or tall tales? A global review of the uptake and impact of NoSQL, blockchain, and big data analytics on the land administration sector,” Land use policy, vol. 83, no. June 2018, pp. 435–448, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Abubakari, C. Richter, and J. Zevenbergen, “Making space legible across three normative frames: The ( non-) registration of inherited land in Ghana,” Geoforum, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Mustaquim and T. Nyström, “Designing information systems for sustainability - The role of universal design and open innovation,” in Advancing the impact of Design Science: Moving from theory to practice:9th International Conference, DESRIT 2014, Miami, FL, USA, May 22-24, 2014. Proceedings, M. C. Tremblay, D. VanderMeer, M. Rothenberg, A. Gupta, and V. Yoon, Eds., Miami: Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp. 1–16. 22 May. [CrossRef]

- L. Pritchett, M. Woolcock, and M. Andrews, “Looking Like a State: Techniques of Persistent Failure in State Capability for Implementation,” Journal of Development Studies, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 1–18, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

| PATHWAYS | DESCRIPTION |

| Governance and Institutions | Measures the governance model, institutional arrangement, structures, and commitment to achieve a successful geospatial information management system. |

| Legal and policy | Focuses on the legal and policy environment and its influence on land information management |

| Financial | Focuses on implementation cost and the financial commitment required to provide a long-term sustainable information system |

| Data | Measures the means of acquiring, organising, integrating, and archiving land information and the overall management of data sharing and reuse |

| Innovation | Focuses on the choice of technology (hardware and software) and how it strategically aligns with the institutional processes |

| Standard | This measures how different information systems communicate and exchange data in a manner that is not subjected to more than one interpretation |

| Partnership | It measures the value of land information through trusted partnerships that acknowledge community needs, organisational needs, and national interests |

| Capacity and Education | Measures the skills, instincts, techniques, and resources needed by an organisation and communities to optimise LIS for decision-making |

| Communication and Engagement | It measures stakeholders’ engagement and input in implementing an information system |

| THEME: PUBLIC PROVISION OF INFORMATION | ||

|---|---|---|

| Land Governance Indicators | Dimensions | |

| LG 16 | Completeness of the land registry | Mapping of registry records |

| Relevant private encumbrances | ||

| Relevant public restrictions | ||

| Searchability of the registry | ||

| Accessibility of registry records | ||

| Timely response to requests | ||

| LG 17 | Reliability of Registry Records | Registry focus on client satisfaction |

| Cadastral/registry info up to date | ||

| LG 18 | Cost-Effectiveness and Sustainability | Cost to register transfer |

| Financial sustainability of the registry | ||

| Capital investment | ||

| LG 9 | Transparency | Fee schedule public |

| Informal payments discouraged | ||

| Evaluation areas | Evaluation Aspects |

|---|---|

| Policy level | Land policy aspects and objectives |

| Historical, political, and social aspects | |

| Land tenure and legal aspects | |

| Financial and economic aspects | |

| Environmental sustainability aspects | |

| Management level | Strategic aspects |

| Institutional and organisational aspects | |

| Human resources and personnel aspects | |

| Cadastral and land administration principles | |

| Operational level | Definition of users, products, and services |

| Aspects affecting the users | |

| Aspects affecting products and services | |

| External factors | Capacity building, education |

| Research and development | |

| Technological supply | |

| Professional aspects | |

| Review process | Review Process |

| User satisfaction | |

| visions and reform |

| Theme | Dimension | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Governance and People | Organisational Framework | Institutional mandates, roles, and responsibilities are clear without overlapping functionalities |

| The land administration process is clearly defined and integrated into the functionalities of the information system | ||

| Positive attitude toward Information, Communication, and Technology (ICT) Adoption | ||

| Policy and Legal Frameworks | Availability of laws and policies to support analogue to digital conversion | |

| The system is ready to process all the different types of land rights, right holders, and restrictions | ||

| Data standards, data privacy, data security, and data sharing options are properly regulated | ||

| Operational environment | Technology | Availability of strategy to implement the system’s specifications (thus strategies to ensure that the computer hardware, software, backups, and storage space needed for effective LIS are available) |

| The availability of user-friendly manuals | ||

| The availability of a user-friendly system | ||

| Data | Data is available with the relevant attributes to be fed into the system | |

| Availability of plan to get a complete cadastral coverage | ||

| Working Environment | Availability of a suitable ergonomic environment | |

| Reliable power supply and internet connection | ||

| Sustainability measures | ICT strategy | Availability of a help desk to provide technical support and assistance |

| Availability of strategy to retain key IT staff (thus if IT staff is well motivated) | ||

| Availability of strategy to protect data, software, and operating system | ||

| Availability of system implementation plan | ||

| Training and Capacity | Availability of IT experts for database, land administration processes, and data and network security. | |

| The staff has adequate training in using the information system | ||

| Availability of a plan to get the capacity available | ||

| Communication Strategy | There is a public awareness campaign with content focusing on all the stakeholders of the information system | |

| Availability of an option for a feedback mechanism |

| INDICATORS | RATINGS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HA | MA | LA | |

| Institutional mandates, roles, and responsibilities are clear without duplication of activities | √ | ||

| The land administration process is clearly defined and integrated into the LIS functionalities | √ | ||

| Positive attitude toward Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) Adoption | √ | ||

| Availability of laws and policies to support analogue to digital conversion | √ | ||

| The LIS is ready to process all the different types of land rights, right holders, and restrictions | √ | ||

| Availability of strategy to implement the system’s specifications (thus strategies to ensure that the computer hardware, software, backups, and storage space needed for effective LIS are available) | √ | ||

| The availability of user-friendly manuals | √ | ||

| The availability of a user-friendly system | √ | ||

| Data is available with the relevant attributes to be fed into the LIS | √ | ||

| Availability of plan to get a complete cadastral coverage | √ | ||

| Availability of a suitable ergonomic environment | √ | ||

| Reliable power supply and internet connection | √ | ||

| Availability of a help desk to provide technical support and assistance | √ | ||

| Availability of strategy to retain key IT staff (thus, if IT staff is well motivated) | √ | ||

| Availability of strategy to protect data, software and operating system | √ | ||

| Proper regulation of data standards, privacy, security and data sharing | √ | ||

| Availability of system implementation plan | √ | ||

| Availability of IT experts for database, land administration processes, data and network security | √ | ||

| The staff has adequate training in using the LIS | √ | ||

| Availability of a plan to get the capacity available | √ | ||

| There is a public awareness campaign with content focusing on all the stakeholders of the LIS | √ | ||

| Availability of an option for a feedback mechanism | √ | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).