1. Introduction

As highlighted in the most recent Global Risk Report of the World Economic Forum [

1], we are currently facing a potential ‘polycrisis’, a critical inflection point that requires a whole-of-society response aimed at building collective foresight and preparedness for short-, medium-, and long-term risks. Although the challenge ahead is very complex, it is also true that risks are invariably accompanied by opportunities for growth that ensure prosperity and environmental sustainability [

2]. In this context, strategic partnerships are more necessary than ever. Moreover, shared responsibility between different stakeholders is crucial when the goal is to not only build resilient societies, but also to change and transform what is no longer working in order to create a stronger, and more prosperous shared future [

3].

Different types of competence have always been key to the successful navigation and management of academic, personal, and professional reality. In this highly uncertain and volatile scenario, even though the basic principles of a discipline are still the cornerstone of a profession, one cannot underestimate the importance of the progressive demand for soft skills [

4]. These include the following: (i) personal competences such as flexibility, ambiguity, tolerance, and motivation; (ii) interpersonal competences such as communication, teamwork, and leadership; and (iii) methodological competences such as creativity, decision making, and conflict transformation. All of these soft skills are more necessary than ever as new professional profiles emerge and are (re)configured at great speed [

5].

According to [

6], 42% of all jobs are now at risk of automation. Strikingly, however, only 12% of hybrid jobs – those requiring both soft and hard skills – are in danger of being eliminated by machines. Therefore, in this Fourth Industrial Revolution, the new metrics [

7] are in the form of a skills genome based on a new professional categorisation [

8], which urgently requires an innovative curriculum in Higher Education [

9]. This new curriculum should combine knowledge with different competences, such as soft skills, so that individuals can develop their full potential and be a catalyst for development in today’s society.

In this new approach, the role of academia would encourage and foment the development of proactive responses to the new form of society that is currently emerging. More than merely a ‘good idea’, it is imperative for adaptation [

10] (p. 11). In this new paradigm of thinking, all processes are interconnected. The focus would no longer be on teaching others how to do things (

savoir-faire), but rather on teaching them how to live their life in a different and more flexible way (

savoir-vivre). This new approach transcends mere employability because it fosters the creation of real wealth and focuses on the true purpose of learning, which is to improve society.

Spanish public universities have long been aware of the need to incorporate this type of training. In Spain, the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA) is responsible for all evaluation, certification, and accreditation in the university system. Its white papers state the contents and competences to be taken into account in an undergraduate degree programme, adapted to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Even though the role of generic or transversal competences is highlighted in the white papers, these competences are rarely explicit in undergraduate course contents. The University of Granada has seen this context as an opportunity to provide graduates with tools that will help them face the challenges of modern society. For this purpose, over the last decade, the University of Granada has been creating a platform for reflection, debate, and action in an effort to integrate these competences in a framework of lifelong learning.

2. A Shift of Paradigm: From Training to Education

In the opinion of many employers, policymakers, researchers, and educators, a degree is no longer enough. Twenty years ago, the main requirement for a job was a university diploma. However, the situation has evolved dramatically. In the world today, many companies are placing less importance on a degree and are now more focused on skills-based hiring [

11]. This priorization of transversal competences in the labour market is reflected in job advertisements [

12] as well as in the expectations and needs of employers [

13]. The fact that emotional intelligence guides career success [

14] is something that is widely acknowledged by recruiters [

15].

The UNESCO, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the European Commission are a two of the institutions that have introduced international educational policies that stress the urgent need to prepare students for a VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) world [

16]. Both organisations emphasize the need for a more competence-based education that bridges the gap between current degree programmes and the needs of society [

17]. Frameworks, agendas, and projects have been launched, and though their application is not worldwide, there is widespread consensus among policymakers that transversal competences should be embedded in formal curricula to enable students to successfully navigate their lives, relations, and career paths, especially since these competences allow them to cope with societal changes, digital transformation, volatile global job markets, and rising radicalisation [

18] (p. 11).

Researchers from different fields are following this trend because students who master these transversal competences, along with more specific technical ones, will be in a more advantageous position in the labor market [

5]. Likewise, they will generate greater social good, enjoy better health, and live longer. Their academic performance will also improve their productivity and engagement [

19].

However, scholars warn us of ill-defined psycho-educational interventions that will supposedly improve the performance and wellbeing of individuals. Commodity forms of these courses are one of the primary targets of criticism [

20]. Transversal competences are not “pills” of competence, detached from specific disciplinary contexts and socio-cultural settings that can be easily acquired. They are far from simple to teach and learn, and can be assigned different values in different professional, political, and cultural contexts [

21].

Although Higher Education Institutions have addressed the issue to a certain extent, there is still a skills gap between learning and the needs of society. More specifically, improvements in student acquisition of transversal competences are still missing [

22]. Given the new demands of society, the university should be an agent of change. Consequently, new curricular designs are now emerging that move from an expert-driven educational model to a student-centred one [

23].

These curricula are increasingly interdisciplinary and will be open to a wider public, not only university students. They will envisage accumulation, with stackable, preferably digital, micro-credentials that students will combine to allow for skilling, upskilling, and reskilling [

24]. The aim is not just to enhance graduate employability, but to prepare students to be lifelong learners and citizens capable of positively influencing social change [

25]. For this to occur, academia needs to move from training to education [

26]. Stronger partnerships between academia, workplace, and society should be created and nurtured, in a revised higher education model that fully intertwines subject-specific and transversal competences in the learning process [

17].

3. The First Teaching Innovation Project: Turning Research into Tools

According to [

27], the second largest daily newspaper in Spain, the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting of the University of Granada (UGR) is one of the leading translation and interpreting faculties both in Spain and abroad. Not surprisingly, its students tend to be high achievers and thus more prone to maladaptive perfectionism which can lead to psychological distress [

28]. However, psychological distress is not something that only affects high-profile students. Various studies report greater stress levels among all undergraduate students when compared to the general population [

29]. In fact, it is estimated that nearly 40% of all university students experience mild to severe depressive symptoms with over 50% predicted to experience some level of depressive symptomatology during their college years [

30]. The ability to cope with cognitive and emotional challenges is thus a desirable aim for every student on a daily basis.

It is within this framework that in 2018, CRAFT.UGR was born. CRAFT.UGR is a teaching innovation project, which was the result of the interaction between mindfulness experts, lecturers, researchers in Translation and Interpreting (T&I) and Experimental Psychology, students, administrative staff, and social stakeholders in Higher Education. The project was aimed at undergraduate students of the Bachelor’s Degree in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada (Spain). The main objective of the project and parallel study was to test whether participation in a course on mindfulness-based techniques could improve specific aspects of cognition, emotional intelligence, creativity, and academic performance inter alia.

To this end, a study was conducted to compare the effects of two mindfulness-based programmes. With the collaboration of researchers from the Mind, Brain and Behaviour Research Centre (CIMCYC) of the UGR, psychological and academic performance measures were taken at different stages of training. Preliminary results suggested that the T&I students that took a mindfulness-based course improved transversal competences such as dispositional mindfulness (i.e., the ability to attend to, be aware of, and accept present-moment experience), adaptive emotional regulation, emotional intelligence, and cultural intelligence. In addition, it was found that both programmes led to a reduction of stress, maladaptive emotional regulation, and spontaneous mind-wandering [

31].

3.1. Chronology, Materials and Methodology

The first year of the project was devoted to designing the study, adapting the programmes, and implementing the administrative procedures to include the new course in the Bachelor’s Degree studies. Approval for the parallel study was received from the UGR Ethics Committee on Human Research (CEIH) and the UGR Human Subjects Protection Review Board. The methodology used was registered in the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) database at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), clinicaltrials.gov, under NCT04392869 registry.

The Faculty of Translation and Interpreting facilitated lecture rooms as well as administrative assistance. To encourage participation in the study, all students that successfully finished the course obtained 4 ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) credits as well as a discount on the original price of the credits. For those students that had a scholarship, a further discount was also available.

During the first term of the second academic year of the project, all undergraduate students were invited to participate both in the course and the study. They had the option of participating only in the study, only in the course, or in both the course and study. In compliance with Spanish and European legislation, all potential participants were asked to give their informed consent, answer a demographic questionnaire to determine their eligibility, and take a battery of tests. Eligible participants were then randomly assigned to either the MBSR group or the CRAFT group.

All measures were uploaded to the UGR LimeSurvey platform, an open-source online survey tool specifically designed to develop, publish, and collect survey responses. This software is recommended by the UGR to present and collect online data for research purposes since it complies with current legislation and ensures that all data protection requirements are met. For additional security guarantees, an institutional email account was created for all communication related to the project. In the same line, all the documentation generated within the project was uploaded and shared on a virtual cloud owned by the UGR.

3.2. The Course and Programmes

Both mindfulness-based programmes lasted for 12 weeks and trained participants to increase their sustained attention and to acquire an accepting and open attitude. Nevertheless, both programmes differed in their methods, intention, and aims.

The MBSR programme is an evidence-based, secular programme originally developed for chronic pain, but which has reported positive results in an array of clinical and nonclinical populations. This programme cultivates awareness of the present moment and non-judgmental attention while promoting stress reduction through a range of formal and informal practices [

32].

The CRAFT programme [

33,

34] is a mindfulness-based programme which systematically combines practices of ancient philosophies, such as yoga and Buddhism, together with more recent disciplines such as mindfulness, emotional intelligence, and positive psychology. The contents are structured in five consecutive modules, whose aim is to cultivate and enhance consciousness, relaxation and regulation, attention, bliss, and transcendence [

35,

36].

Students from both groups received an adapted and extended version of the MBSR and CRAFT programmes. Both programme instructors were fully qualified and accredited, and had ample experience in this kind of psycho-educational intervention.

4. The Second Teaching Innovation Project: Scaling Up the Experience

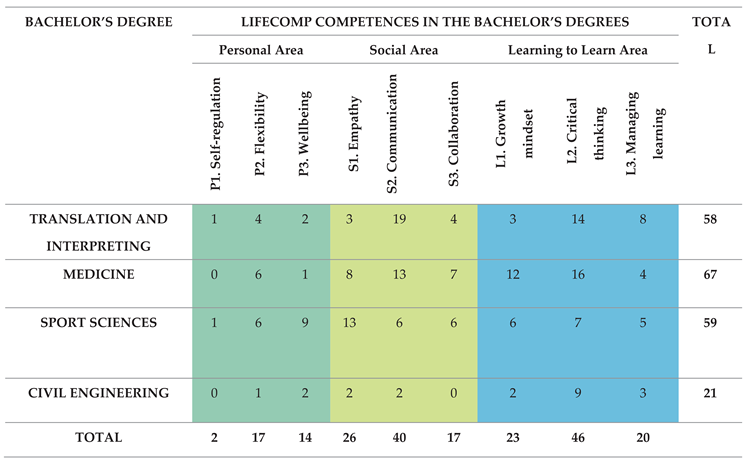

Different academic and professional profiles demand different transversal competences [

37]. With a view to exploring how different disciplines codify transversal competences, a second innovation project was launched to scale up the results to degree programmes in Humanities, Engineering, Bioscience, and Physical Education. These four programmes are given at the UGR, in the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, School of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Medicine, and Faculty of Sport Sciences, respectively.

The objectives were the following: (1) to provide content for LifeComp, the European key competence framework, and design the structure and content of a 3 ECTS programme to be taught in the second term of the following academic year in four degree programmes of the UGR; (2) to design and implement a parallel empirical study that measures the cognitive-emotional impact of such a programme in the short-, medium-, and long-term; and (3) to issue, validate, and accredit these competences, together with public and private institutions in the sector, in the official undergraduate curriculum.

4.1. Chronology, Materials and Methodology

Similarly to the first innovation project, the first year was devoted to the design of the study as well as the administrative procedures to formally include the course in the Bachelor’s Degree Programme and obtain approval from the UGR Ethics Committee on Human Research (CEIH) and the UGR Human Subjects Protection Review Board. Participants were randomized and assigned to two groups, i.e., the MBSR group and the

Más Presente group. This time, the programme proposal by the University of Granada,

Más Presente, is designed following a base structure, UGRComp, which in turn follows the European framework for Personal, Social and Learning to Learn Key Competence, LifeComp [

38,

39].

During the first year, in order to provide content to the base structure of the programme, a preliminary study was carried out by UGR experts in curricular design to explore the importance of the LifeComp competences in each of the four degrees. The research consisted in finding, typifying, and counting the transversal competences as listed in the ANECA white papers and matching them to the corresponding LifeComp competences (see

Table 1).

According to this report, different academic profiles have different needs and expectations regarding transversal competences as codified in LifeComp European framework. Some room for programme adaptation depending on these four academic profiles was allowed.

The faculties and technical school participating in the study facilitated the use of lecture rooms and gave students 3 ECTS credits in exchange for their participation. The project was presented to the Vice-Rectorate for Equality, Inclusion, and Sustainability of the UGR, and was included in the strategic plan of the University of Granada.

During the first term of the second academic year, all students gave their informed consent and were invited to participate in the course as well as in the study. The students took the courses in the second term and completed tests before and after the intervention. As in the previous project, all necessary precautions were taken to comply with legislation ensuring data protection.

4.2. The Course and Programmes

To guarantee the use of a common language and logic for the further development and flexible implementation at the Higher Education level [

13] the base structure of the new programme was based on the European LifeComp key competence framework [

38,

39].

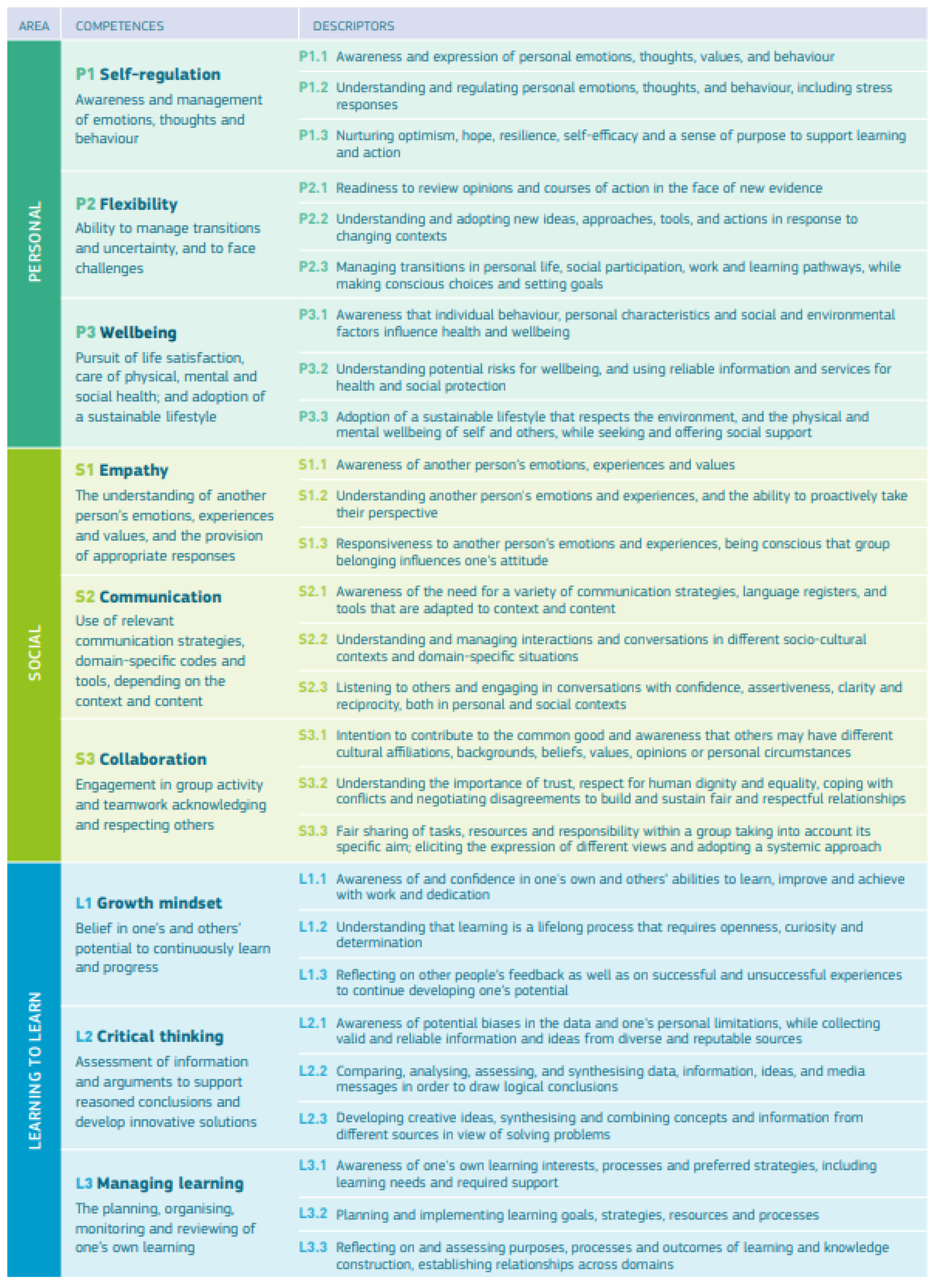

LifeComp is composed of nine malleable, interdependent, and culturally-shaped competences, structured in three intertwined areas: Personal, Social, and Learning to Learn. Each competence is the result of research by experts and stakeholders and is further divided into three levels of development: awareness, understanding, and action.

Figure 1.

LifeComp framework [

38] (p. 20).

Figure 1.

LifeComp framework [

38] (p. 20).

Experts in curricular design, psychologists, and pedagogues worked together to provide content to a structure based on LifeComp framework. As depicted in the

Supplementary Material 1, a base structure was created, on which to build the

Más Presente programme so that it could be adapted to each academic and professional context. This base structure was called UGRComp. Its descriptors were extracted from LifeComp, and its contents followed the guidelines in [

38] for developing the nine competences and three areas. Assessment criteria were provided, and various evidence-based references were suggested for further programme content development.

Didactic material was designed and compiled to provide and complement the teaching of the contents. The assessment material was also designed and compiled to give the students individual and group feedback on their progress in competence acquisition, as well as to provide the necessary qualifications for credit validation (See

Supplementary Material 1). In consonance with LifeComp experts [

18] the 3 ECTS credit course covered the three core competences (i.e., Self-regulation, Empathy, and Growth Mindset). In other words, it cross-cut framework elements that are pre-requisites for developing other framework areas. Special attention was given to the scalability of concepts, procedures, and attitudes as well as to the connection between the different competences and areas. For pedagogical reasons, six independent but scalable items were foreseen as contents for each level of development, and the assessment criteria were designed accordingly.

The resulting programme, Más Presente, goes beyond the traditional cognitive and behavioural approaches. Its goal is not to change thoughts and emotions, but rather to observe them. The idea is to know how they have been generated and to focus efforts on action aligned with values. Changing thoughts and emotions is thus a by-product of the process rather than an end in itself.

5. The Industry-Academia Partnership: A Strategic Alliance Based on Sustainability

Over the centuries, human beings have evolved by successfully adapting to and dealing with crises of all kinds. The transformation that society is now demanding involves a paradigm shift that integrates global welfare, sustainability, and development. It is no longer sufficient to satisfy individual or group needs by modifying the environment. Since this signifies entering into conflict with competitors to secure the necessary resources, this pattern is no longer viable. By limiting competitive stimuli, progress not only becomes more inclusive, but advances at a more humane pace. This would alleviate stress on the planet’s resources and make growth sustainable. Uncontrolled progress is not a path to the future, but rather to extinction. Living in harmony with the environment benefits the environment, but also allows us to optimize our efforts to move forward without slipping backwards at an accelerated pace [

41].

Nonetheless, progress towards sustainable development goals has been largely disappointing. For this reason, there is now an urgent need for transformational change at multiple levels. This change should focus on skills for inner development with a view to laying stronger foundations for improving our capacity to manage increasingly complex societal challenges [

42] (p. 2). We thus need to take a step further in this transformative setting and equip learners with knowledge, skills, and attitudes that will enable them to become agents of change who are able to shape sustainable futures for everyone. We need to help them acquire greater awareness of inner dimensions, such as mindsets, values, and worldviews that influence transformative pathways and conceptions of sustainability [

43,

44]. Such challenges cannot be addressed by government, business, or civil society alone. The state of the world can only be improved by a systemic approach and the pursuit of strategic alliances that unite all stakeholders and allow us move forward together.

5.1. Chronology, Materials and Methodology

The Cívitas Group

1, a nationwide property developer with a strong commitment to sustainability and innovation, has joined with the University of Granada to promote a transformation involving all stakeholders. The Cívitas-UGR Chair is a strategic alliance stemming from interaction between business and academia in the areas of sustainability, innovation, and training.

For the 2022-2024 biennium, as part of the UGR 2031 Strategic Plan, the training and research of the Chair will focus on two main areas. On the one hand, it plans to actively promote sustainable construction and structural wood products to reduce the carbon footprint, and on the other, it will target transversal competences for sustainable human development. To this end, the Chair relies on a highly qualified multidisciplinary group of architects, building engineers, environmental engineers, lawyers, and educational psychologists, who will work within the framework of various national and European research projects. The activities of the Chair include initiatives of visibility and awareness, training, registration of new patents and interventions in projection and urban planning. The other area of focus is learning for environmental sustainability, in reference to transversal and sustainability competences, a course and a parallel study have been launched that will provide research and training in these competences at a degree level. The methodology used in this study has been registered as a clinical trial, i.e., behavioural intervention, in

clinicaltrials.gov under ID NCT05598944 and NCT05775978 (See

Supplementary Material 3). The activities of the Chair in this area include training courses in sustainable human development specifically tailored for undergraduate students and teaching staff, course accreditation and assessment, and clinical research on transversal competences. The courses have been approved by the different vice-rectorates and the corresponding accreditation will be provided.

The two ends of the Chair, i.e., sustainable construction and competence-based education, join together to overcome the cognitive dissonance that comes from knowing about an issue but lacking the agency to act. Based on previous experience, the Chair aims at building a shared understanding that acts as a catalyst for transformative learning and acting for environmental sustainability [

43] (p. 6).

5.2. The Courses and Programmes

Two different courses are designed and offered to undergraduate and graduate students of the University of Granada. The aim is not only to integrate the necessary technical and specific knowledge in the curriculum, but also to incorporate competences, attitudes and values that promote responsible agency for sustainable futures.

The Diploma on Wood Structures Calculation Applied to Projects is a postgraduate course that is launched in collaboration with the European project LifeWood for Future (LIFE20 CCM/ES/001656). It offers training to architects and engineers who are interested in innovative manufacturing processes and low ecological footprint construction of buildings (See

Supplementary Material 2). The objective of this course is twofold; on one hand, to raise awareness among building professionals of the urgency to provide sustainable solutions to current challenges and, on the other, to provide these experts with the necessary knowledge and tools to accomplish the task.

The other course builds on the experience of previous projects and embeds sustainability competences following the European GreenComp framework [

43]. Though all competences are interwoven and interdependent, participants are trained in the three LifeComp core elements with a strong focus on Promoting Nature, Critical Thinking, Adaptability and Individual Initiative, from GreenComp (See

Table 2).

Didactic materials have been designed, compiled and adapted to this new frame. The programme has been offered to other members of the university community such as academic and research staff, or administrative and support staff. Businesses and firms have also shown interest and have joined in.

Last but not least, the Chair currently collaborates with the governance structure of the UGR mainly through two if its vice-rectorates. On the one hand, it cooperates with the Vice-rectorate for Quality, Teaching Innovation and Undergraduate Studies in the Plan AcademiaUGR by coordinating different courses aimed at enhancing transversal and governance competences among the teaching and research staff (PDI); these courses have a target population of more than 3,700 PDI. On the other, the Chair works closely with the Vice-rectorate for Infrastructure and Sustainability in the publication of a series of monographs on trends and innovation in construction materials for a sustainable future.

6. Discussion, Challenges and Possible Pitfalls

Soft skills have traditionally been conceived as something that is learned ‘at home’, or as traits that one is born with. These skills are usually regarded as generic, context-independent, and much easier to teach and learn than the harder, more technical ones. However, soft skills are anything but ‘soft’. On the contrary, they are extremely complex and grounded in professional norms. Not only are they difficult to teach and learn, they are differentially valued, depending on the profession and situation [

21] (p. 31). In addition, soft skills are certainly not non-cognitive, as they have been sometimes called [

45], because cognition is intimately related to feelings and emotions [

46]. The research and training required to truly understand these skills is both multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary. Moreover, collaboration between industry and academia is essential so that universities can prepare individuals to contribute to society.

There is now a broad consensus that sustainability is no longer exclusively focused on the environment, but has widened its scope to encompass both society and the balance between humans and the earth [

47]. Likewise, universities have begun to play a key role in the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through education, research, and cooperation with industries. However, despite this clear trend, there is no one-size-fits-all solution because needs, engagement, and contributions vary considerably from one country to another. Each sociocultural context is different. What works in one sociocultural and professional context may not work so well in another, or rather the combination of competences may well vary across different disciplines and cultures. In increasingly fragmented societies, the capacity of leaders to bridge gaps and generate broad coalitions is as difficult as it is necessary [

2]. To develop effective psycho-educational interventions that envisage these complexities, experts from a broad range of disciplines, practitioners, and industries will need to work together and listen carefully to one another.

One of the main challenges encountered stems from the nature of the project itself. The problem is that it does not fit into any of the conventional slots (i.e., research, training and governance) of the traditional public university system. This project does not belong to only one of these areas, but rather is a blend of all three. Needless to say, this poses challenges in terms of funding, organisation, coordination, and personnel among others. In order to transform research into tools and develop proactive responses to the new society that is currently emerging, the system should be able to accommodate this kind of polyhedral projects. This flexibility would allow the university to anticipate changes, incorporate findings, and respond quickly on the basis of existing evidence [

10].

Finally, there is the danger of isolated and decontextualized psycho-educational interventions. Well-meaning initiatives targeting only one problem area almost always end in failure because they are either ineffective or lead to unintentional consequences. Various studies reflect the darker side of transversal competences. Despite their evident desirability, when these competences are used dysfunctionally, they become detrimental. This was the case of empathy. [

48,

49], compassion [

50], and resilience [

51], to name only three. This issue can only be addressed by taking a holistic approach and embracing a systemic leadership that fosters strategic networks and encourages organisations to advance toward a shared goal [

52].

7. Conclusions: What Lies Ahead

Crises generally reveal unexpected pathways. Traditionally, it has been the public sector that has invested in medium- and long-term proposals. However, now private sector companies, committed to improving society, are also joining the cause, and local communities are supporting them. This is a unique opportunity to reconcile growth and sustainability in the context of strategic and systemic alliances; is is in the intersection of different systems where we can develop a macroscale, system oriented decision in order to enact a sustainable future [

53]. In this context, in addition to long-term focus and a commitment to effectively address the challenges that lie ahead, it is necessary to reflect on the role of Higher Education institutions as agents in this process. Universities must be able to fluidly communicate with society, and be aware of the social needs and demands that transcend the purely professional sphere. This is the only way to achieve a true transfer of knowledge.

The role of education in the development of transversal competences in a lifelong learning context, whether in the private or public sector, has become increasingly important [

54]. This new context is a lever of change that opens the door to new opportunities for those trained in the necessary skills. Consequently, the main challenge for higher education institutions lies in how to balance hard and soft skills in curricula [

4] because transversal competences can be acquired through intentional training with the help of empirically supported psycho-educational interventions.

However, our proposal offers a great deal more than commodified courses that increase the value and productivity of graduates. We are committed to a concept of employability that goes beyond the traditional view and binds macroscale measures that leads to a sustainable future [

53]. We advocate a change of paradigm that rejects the return on investment (ROI) of a college degree. Instead, it invests in the infrastructure needed to enhance the social transformation and long-term well-being of students [

55]. The best guarantee for a future marked by automation and robotisation is the development of what differentiates us from machines, namely, critical thinking, civic humanism, collaborative work, creativity, and the capacity to inspire [

56] (p. 224). The ultimate goal is to be neither producers nor consumers. The type of the person we are looking for is more an individual than a citizen, a unique being who interacts with others and collaborates with them as a node in a network, not as a link in a chain or a cog in a machine [

41]. We therefore actively support the study and training in personal, social and lifelong learning competences, which would be integrated in the curricular development and accreditation.

At the same time, we advocate the intrinsic complexity of sustainability which requires systemic change rather than adaptation, a whole-institution approach to promote transformational behaviors [

57,

58]. In this context, we advocate for collaboraton at different levels, from training to research, from outreach to governace. Higher education institutions need to “walk the talk” and go far beyond the mere information and embed sustainability in their deeper structure.

This paper is meant to challenge, inspire, and encourage readers to ask themselves, wherever they are, what they can do to grow and to help others grow. It is not our mission to give definitive answers since a one-size-fits-all approach to education reform is unlikely to work. However, it is our goal to create a space for reflection and debate, in every possible socio-cultural context that leads to awareness, understanding, and action.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. The programme content, assessment criteria and evidence-based references for Self-regulation (Awareness-Understanding-Action) is available under Supplementary Material 1. The programme content and description of the Diploma on Wood Structures Calculation Applied to Projects offered by the International School for Postgraduate Studies of the University of Granada (Spain) is available under Supplementary Material 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, structure, writing – original draft preparation: MGQ; Writing – review and editing: BRV, CVL, ECA, JGP, MGQ, MHS, PPJ; Programme content design and methodology: CVL, PPJ, MGQ and MHS; Programme alignment with curricular pedagogy: JGP; Resources: ECA and MGQ. Supervision: ECA, MGQ and MHS; Project administration: BRV and MGQ; Funding acquisition: MGQ.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Plan for Teacher Training and Innovative Teaching Practice (FIDO), 2018-2020 and 2020-2022 (codes PID 43/2018-2020 and PID 20-106/2020-2022), Quality, Teaching Innovation and Planning Unit (UCIDP) of the University of Granada (Spain). From 2022-2024, it has been co-funded by the former Vice-Rectorate for Equality, Inclusion and Sustainability, the Vice-Rectorate for Quality, Teaching Innovation and Undergraduate Studies, and the Cívitas-UGR Chair: Sustainability, Innovation and Development, all of them from the University of Granada (Spain).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study methodology was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research (CEIH) of the University of Granada, Spain (protocol codes and dates: 867/CEIH72019, 2266/CEIH/2021 and 2972/CEIH/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of the studies depicted in this paper will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students and teaching staff who have trusted in the project and have enrolled in the courses; they have encouraged us to move forward. The authors also would like to thank the researchers from the Mind, Brain and Behaviour Research Centre (CIMCYC) from the University of Granada (Spain), whose expert contribution is indispensable in a study of this nature. Thanks to Presentia and ConscienciArte centers for their support and training the courses teachers. Finally, the authors would like to thank Pamela Faber, from the Department of Translation and Interpreting of the University of Granada (Spain) for proofreading the final version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Economic Forum (WEF). 2023. We’re on the Brink of a ‘Plycrisis’ – How Worried Should We Be? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/polycrisis-global-risks-report-cost-of-living/#:~:text=The%20Global%20Risks%20Report%202023,emerging%20risks%20threatens%20a%20polycrisis (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- OECD. 2022. Trends Shaping Education. Paris: OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Sellman, Edward M., and Gabriella F. Buttarazzi. 2020. Adding Lemon Juice to Poison–Raising Critical Questions about the Oxymoronic Nature of Mindfulness in Education and its Future Direction. British Journal of Educational Studies 68 (1): 61-78. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Encinas, Adriana, and Jasmina Berbegal-Mirabent. 2023. Who Gets a Job Sooner? Results from a National Survey of Master’s Graduates. Studies in Higher Education 48 (1): 174–88. [CrossRef]

- Alhloul, Abdelkarim, and Eva Kiss. 2022. Industry 4.0 as a Challenge for the Skills and Competencies of the Labor Force: A Bibliometric Review and a Survey. Sci 4 (3). [CrossRef]

- Burning Glass Technologies. 2019. The Hybrid Job Economy: How New Skills are Rewriting the DNA of the Job Market. Available online: https://www.burning-glass.com/wp-content/uploads/hybrid_jobs_2019_final.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Arroyo, Javier. 2019. Un currículum más allá del aula. El País. Available online: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2019/10/13/actualidad/1570981445_198065.html (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Vasselina, Ratcheva, Leopold Till Alexander, and Zahidi Saadia. 2020. Jobs of Tomorrow: Mapping Opportunity in the New Economy. World Economic Forum.

- Garner, Benjamin R., Michael Gove, Cesar Ayala, and Ashraf Mady. 2019. Exploring the Gap between Employers’ Needs and Undergraduate Business Curricula: A Survey of Alumni Regarding Core Business Curricula. Industry and Higher Education 33 (6): 439-447. [CrossRef]

- Moscardini, Alfredo. O., Rebecca Strachan, and Tetyana Vlasova. 2020. The Role of Universities in Modern Society. Studies in Higher Education. 47 (4): 812-830. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Joseph B., Christina Langer, and Mathew Sigelman. 2022. Skills-Based Hiring Is on the Rise. Harvard Business Review Digital Articles, February.

- Khaouja, Imane, Ghita Mezzour, Kathleen M. Carley, and Ismail Kassou. 2019. Building a Soft Skill Taxonomy from Job Openings. Social Network Analysis and Mining 9 (1): 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ayuso, Pablo, María del Mar Haro-Soler, and Mercedes García de Quesada. 2022. Are We Teaching What They Need? Going beyond Employability in Translation Studies. Hikma 21 (2): 321-345. [CrossRef]

- Urquijo, Itziar, Natalio Extremera, and Garazi Azanza. 2019. The Contribution of Emotional Intelligence to Career Success: Beyond Personality Traits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (23): 4809. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Elisabeth T., Madalena Vilas-Boas, and Cátia F. C. Rebelo. 2020. University Curricula and Employability: The Stakeholders’ Views for a Future Agenda. Industry and Higher Education 34 (5): 321-329. [CrossRef]

- Hadar, Linor L., Oren Ergas, Bracha Alpert, and Tamar Ariav. 2020. Rethinking Teacher Education in a VUCA World: Student Teachers’ Social-Emotional Competencies during the Covid-19 Crisis. European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (4): 573-586. [CrossRef]

- Birtwistle, Tim, and Robert Wagenaar. 2020. Re-Thinking an Educational Model Suitable for 21st Century Needs. In European Higher Education Area: Challenges for a New Decade. [CrossRef]

- Caena, Francesca, and Yves Punie. 2019. Developing a European Framework for the Personal, Social & Learning to Learn Key Competence (LifEComp). Literature Review & Analysis of Frameworks. EUR 29855 EN, JRC117987. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Lambert, Louise, Tim Lomas, Margot P.van de Weijer, Holli Anne Passmore, Mohsen Joshanloo, Jim Harter, Yoshiki Ishikawa, et al. 2020. Towards a Greater Global Understanding of Wellbeing: A Proposal for a More Inclusive Measure. International Journal of Wellbeing 10 (2): 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Zack. 2016. A Meta-Critique of Mindfulness Critiques: From McMindfulness to Critical Mindfulness. In Handbook of Mindfulness: Culture, Context and Social Engagement, 153–66. [CrossRef]

- Hora, Matthew T., Ross J. Benbow, and Bailey B. Smolarek. 2018. Re-Thinking Soft Skills and Student Employability: A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 50 (6): 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Succi, Chiara, and Magali Canovi. 2019. Soft Skills to Enhance Graduate Employability: Comparing Students and Employers’ Perceptions. Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1834–47. [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, Robert. 2021. Evidencing Competence in a Challenging World. European Higher Education Initiatives to Define, Measure and Compare Learning. International Journal of Chinese Education 10 (1): 22125868211006928. [CrossRef]

- Hill, Michelle A., Tina Overton, Russell R. A. Kitson, Christopher D. Thompson, Rowan H. Brookes, Paolo Coppo, and Lynne Bayley. 2022. ‘They Help Us Realise What We’re Actually Gaining’: The Impact on Undergraduates and Teaching Staff of Displaying Transferable Skills Badges. Active Learning in Higher Education 23 (1): 17-34. [CrossRef]

- Miller, Kelly K., Trina Jorre de St Jorre, Jan M. West, and Elizabeth D. Johnson. 2020. The Potential of Digital Credentials to Engage Students with Capabilities of Importance to Scholars and Citizens. Active Learning in Higher Education 21 (1): 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Haro-Soler, Maria del Mar, and Don Kiraly. 2019. Exploring Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Symbiotic Collaboration with Students: An Action Research Project. Interpreter and Translator Trainer 13 (3): 255-270. [CrossRef]

- El Mundo. 2022. Dónde estudiar Traducción e Interpretación. Available online: https://www.elmundo.es/especiales/ranking-universidades/donde-estudiar-traduccion-e-interpretacion.html (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Rice, Kenneth G., Brooke A. Leever, John Christopher, and J. Diane Porter. 2006. Perfectionism, Stress, and Social (Dis)Connection: A Short-Term Study of Hopelessness, Depression, and Academic Adjustment among Honors Students. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53 (4): 524-534. [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, Srividya. 2017. Mindfulness, Stress Coping and Everyday Resilience among Emerging Youth in a University Setting: A Mixed Methods Approach. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 22 (3): 308–21. [CrossRef]

- Pogrebtsova, Ekaterina, Jacqueline Craig, Alexandra Chris, Deirdre O’Shea, and M. Gloria González-Morales. 2018. Exploring Daily Affective Changes in University Students with a Mindful Positive Reappraisal Intervention: A Daily Diary Randomized Controlled Trial. Stress and Health 34 (1): 46–58. [CrossRef]

- Cásedas, Luis, María J. Funes, Marc Ouellet, and Mercedes García de Quesada. 2022. Training Transversal Competences in a Bachelor’s Degree in Translation and Interpreting: Preliminary Evidence from a Clinical Trial. Interpreter and Translator Trainer 17 (2): 193-210. [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2003. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10 (2). [CrossRef]

- Posadas de Julián, Pilar. 2017. Programa CRAFT en el marco del Proyecto MACF (Mundo Atento, Consciente y Feliz) basado en Mindfulness, Yoga, Psicología Positiva y Sugestopedia orientado a las Enseñanzas de Régimen Especial: Enseñanzas Artísticas e Idiomas. Asiento Registral 04/2017/3160.

- Posadas de Julián, Pilar. 2019. Programa CRAFT. Mindfulness, Inteligencia Emocional, Psicología Positiva y Yoga en Educación. Granada: Educatori.

- Bartos, L. Javier, María J. Funes, Marc Ouellet, M. Pilar Posadas, and Chris Krägeloh. 2021. Developing Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Yoga and Mindfulness for the Well-Being of Student Musicians in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology 12. [CrossRef]

- Bartos, L. Javier, María J. Funes, Marc Ouellet, M. Pilar Posadas, Maarten A. Immink, and Chris Krägeloh. 2022. A Feasibility Study of a Program Integrating Mindfulness, Yoga, Positive Psychology, and Emotional Intelligence in Tertiary-Level Student Musicians. Mindfulness 13 (10). [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, Miguel-Angel. 2010. How Should Transversal Competence Be Introduced in Computing Education? ACM SIGCSE Bulletin 41 (4): 95-98. [CrossRef]

- Sala, Arianna, Yves Punie, Vladimir Garkov, and Marcelino Cabrera Giráldez. 2020. LifeComp: The European Framework for Personal, Social, and Learning to Learn Key Competence. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Caena, Francesca, and Cristina Stringher. 2020. Hacia Una Nueva Conceptualización del Aprender a Aprender. Aula Abierta 49 (3): 207-216.

- Lizarte, Emilio Jesús, José Gijón, and Inmaculada Ávalos. 2023. Selection and definition of transversal competences for training design in Higher Education. Unpublished manuscript, electronic file.

- Gómez de Ágreda, Ángel. 2021. Un mundo feliz no es un mundo perfecto. En busca de una sociedad dinámica, flexible y sostenible. Telos. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/un-mundo-feliz-no-es-un-mundo-perfecto/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Kemp, Andrew H., and Darren J. Edwards. 2022. An Introduction to the Complex Construct of Wellbeing, Societal Challenges and Potential Solutions. In Broadening the Scope of Wellbeing Science, 1–11. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Guia, Ulrike Pisiotis, and Marcelino Cabrera Giraldez. 2022. GreenComp – The European sustainability competence framework. Edited by Margherita Bacigalupo, and Yves Punie. EUR 30955 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, ISBN 978-92-76-46485-3. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Kira J., and Robert B. Gibson. 2022. A Novel Framework for Inner-Outer Sustainability Assessment. Challenges 13 (2): 64. [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, Jennifer, Aljoscha C. Neubauer, and Anna Ortner. 2018. The Prediction of Professional Success in Apprenticeship: The Role of Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Abilities, of Interests and Personality. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training 5 (2): 82-111. [CrossRef]

- Cesario, Joseph, David J. Johnson, and Heather L. Eisthen. 2020. Your Brain Is Not an Onion With a Tiny Reptile Inside. Current Directions in Psychological Science 29 (3): 255-260. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Xi, Angel Calderon, and Hamish Coates. 2022. Universities and SDGs: Evidence of Engagement and Contributions, and Pathways for Development. Policy Reviews in Higher Education 7 (1): 56-77. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Michael A. 2003. Shielding Yourself from the Perils of Empathy: The Case of Sign Language Interpreters. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 8 (2): 207-213. [CrossRef]

- Langstraat, Lisa, and Melody Bowdon. 2011. Service Learning and Critical Emotion Studies: On the Perils of Empathy and the Politics of Compassion. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 17 (2): 5-14.

- Wentzel, Dorien, and Petra Brysiewicz. 2014. The Consequence of Caring Too Much: Compassion Fatigue and the Trauma Nurse. Journal of Emergency Nursing 40 (1): 95-97. [CrossRef]

- Mahdiani, Hamideh, and Michael Ungar. 2021. The Dark Side of Resilience. Adversity and Resilience Science 2 (3): 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Stephanie, Daisha Merritt, Robin Roberts, and Daryl Watkins. 2022. Systemic Leadership Development: Impact on Organizational Effectiveness. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 30 (2): 568-588. [CrossRef]

- Eberz, Sarah, Sandra Lang, Petra Breitenmoser, and Kai Niebert. 2023. Taking the Lead into Sustainability: Decision Makers’ Competencies for a Greener Future. Sustainability 15 (6): 4986. [CrossRef]

- Adel, Amr. 2022. Future of Industry 5.0 in Society: Human-Centric Solutions, Challenges and Prospective Research Areas. Journal of Cloud Computing. [CrossRef]

- Hora, Matthew T., Rena Yehuda Newman, Robert Hemp, Jasmine Brandon, and Yi-Jung Wu. 2020. Reframing Student Employability: From Commodifying the Self to Supporting Student, Worker, and Societal Well-Being. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 52 (1): 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Fundación Telefónica. 2020. Informe Sociedad Digital en España 2019. Revista de Occidente. Available online: https://publiadmin.fundaciontelefonica.com/index.php/publicaciones/add_descargas?tipo_fichero=pdf&idioma_fichero=es_es&title=Sociedad+Digital+en+Espa%C3%B1a+2019&code=699&lang=es&file=SdiE_2019.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Bauer, Mara, Inka Bormann, Benjamin Kummer, Sebastian Niedlich, and Marco Rieckmann. (2018). Sustainability governance at universities: Using a governance equalizer as a research heuristic. Higher Education Policy 31: 491-511.

- Holst, Jorrit. 2023. Towards coherence on sustainability in education: a systematic review of Whole Institution Approaches. Sustainability Science 18 (2): 1015-1030.

- Ardelt, Monika, and Sabine Grunwald. 2018. The Importance of Self-Reflection and Awareness for Human Development in Hard Times. Research in Human Development 15 (3–4): 187–99. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, Alan, Disa Sauter, Jessica L. Tracy, and Dacher Keltner. 2019. Mapping the Passions: Toward a High-Dimensional Taxonomy of Emotional Experience and Expression. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 20 (1): 69–90. [CrossRef]

- Pace-Schott, Edward F., Marlissa C. Amole, Tatjana Aue, Michela Balconi, Lauren M. Bylsma, Hugo Critchley, Heath A. Demaree, et al. 2019. Physiological Feelings. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 103: 267-304. [CrossRef]

- Winstone, Naomi, and David Carless. 2019. Designing Effective Feedback Processes in Higher Education: A Learning-Focused Approach. New York: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, Hefer. 2022. Sustaining Motivation and Academic Delay of Gratification: Analysis and Applications. Theory into Practice 61 (1): 75–88. [CrossRef]

- Datu, Jesus Alfonso D., Charlie E. Labarda, and Maria Guadalupe C. Salanga. 2020. Flourishing Is Associated with Achievement Goal Orientations and Academic Delay of Gratification in a Collectivist Context. Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (4): 1171–82. [CrossRef]

- Wadlinger, Heather A., and Derek M. Isaacowitz. 2011. Fixing Our Focus: Training Attention to Regulate Emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 (1): 75–102. [CrossRef]

- Woodyatt, Lydia, Michael Wenzel, and Matthew Ferber. 2017. Two Pathways to Self-Forgiveness: A Hedonic Path via Self-Compassion and a Eudaimonic Path via the Reaffirmation of Violated Values. British Journal of Social Psychology 56 (3): 515–36. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Amy J., Courtney M. Holmes, and Denise Henning. 2020. A Changing World, Again. How Appreciative Inquiry Can Guide Our Growth. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 2 (1): 100038. [CrossRef]

- Lomas, Tim, Lea Waters, Paige Williams, Lindsay G. Oades, and Margaret L. Kern. 2021. Third Wave Positive Psychology: Broadening towards Complexity. Journal of Positive Psychology 16 (5): 660–74. [CrossRef]

- Muller, Rick. 2017. Suffering and the Human Terror. Anthropology of Consciousness 28 (2): 156–64. [CrossRef]

- Smeets, Elke, Kristin Neff, Hugo Alberts, and Madelon Peters. 2014. Meeting Suffering with Kindness: Effects of a Brief Self-Compassion Intervention for Female College Students. Journal of Clinical Psychology 70 (9): 794–807. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).