Submitted:

13 March 2024

Posted:

14 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

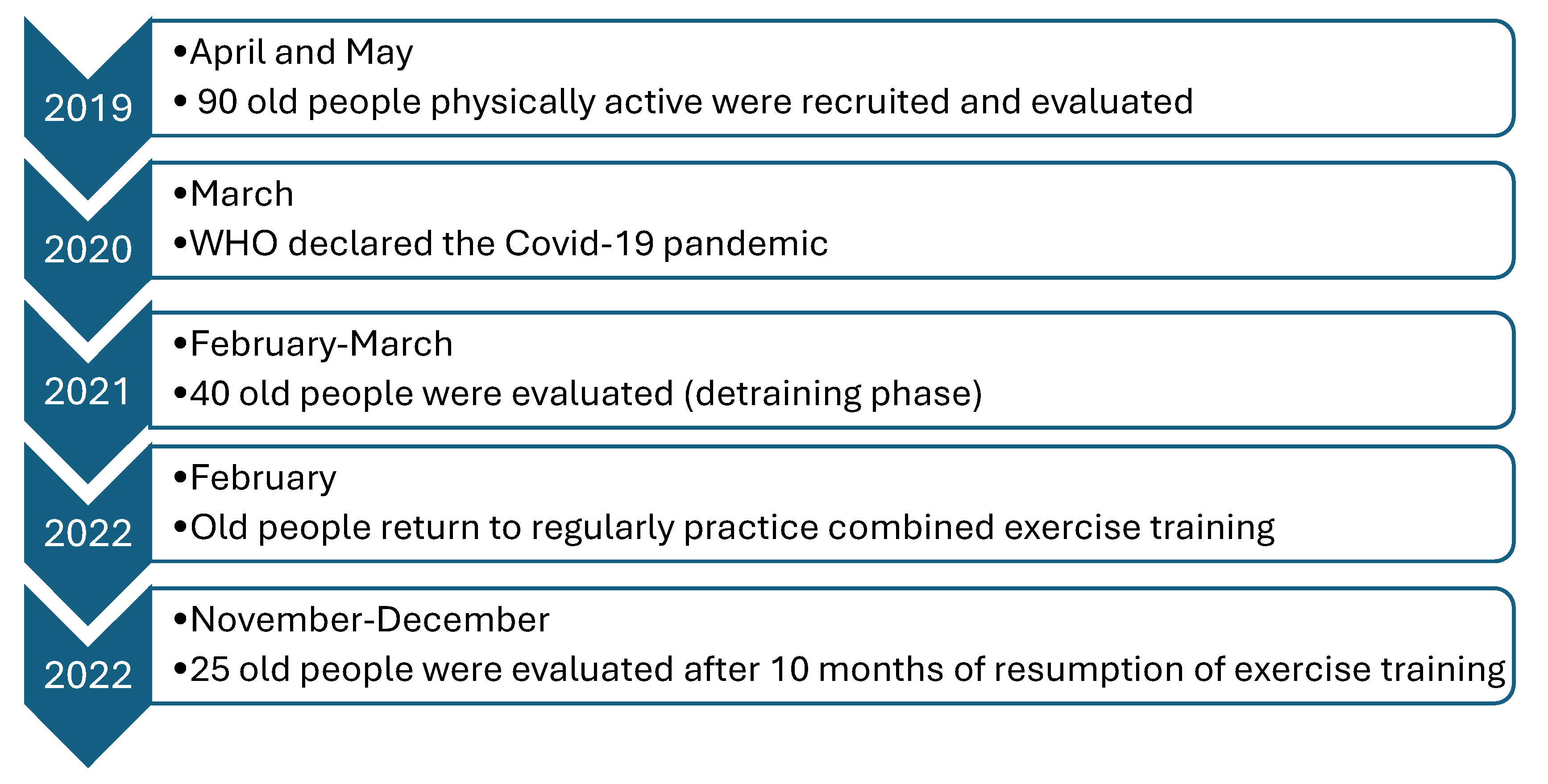

Participants and Study Design

Combined Exercise Training Program

Anthropometric Data and Physical Tests

Blood Sample Collection and Analysis

Statistical Analysis

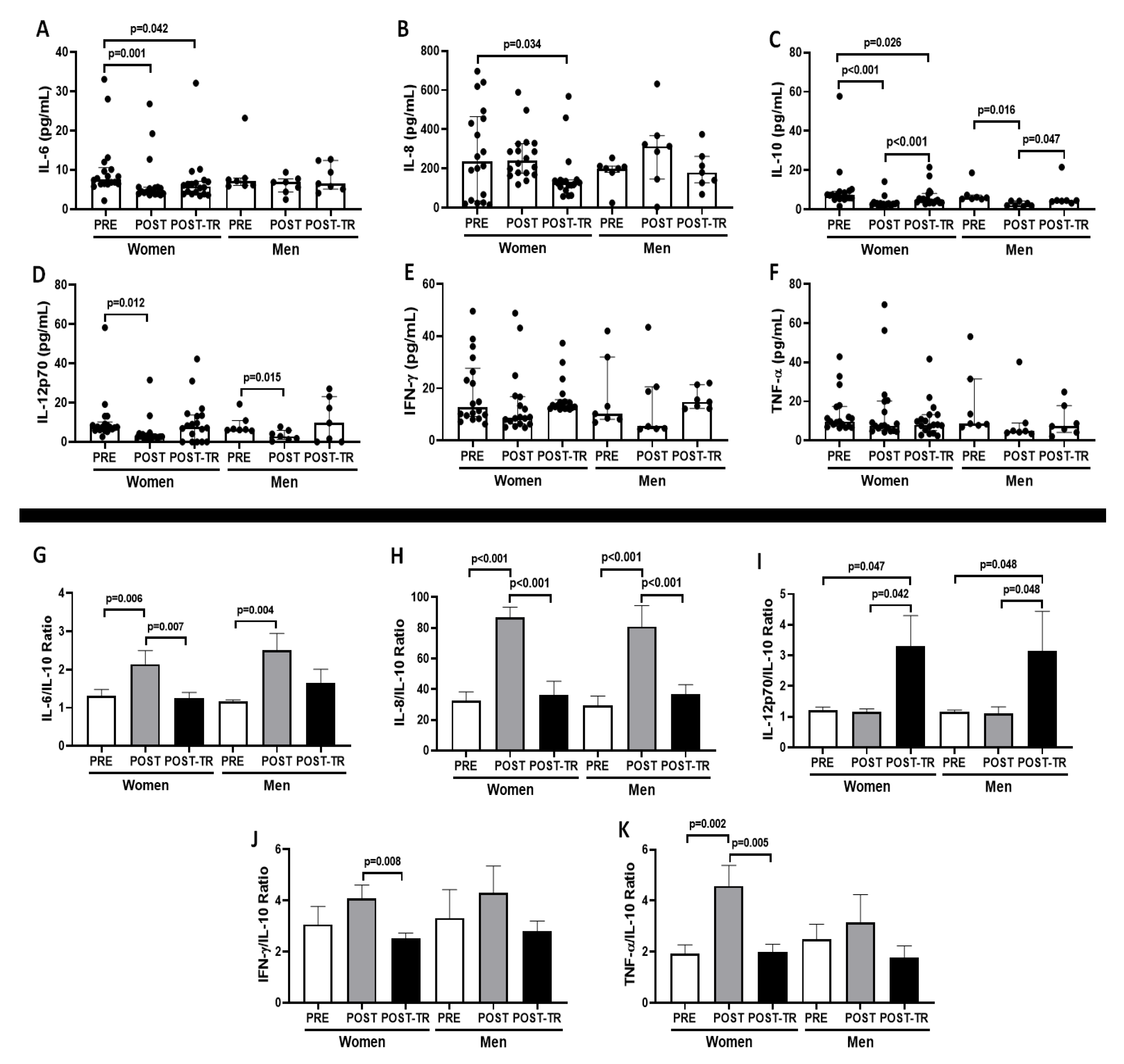

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

References

- Conway, J.; Certo, M.; Lord, J.M.; Mauro, C.; Duggal, N.A. Understanding the role of host metabolites in the induction of immune senescence: Future strategies for keeping the ageing population healthy. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 1808–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moqri, M.; Herzog, C.; Poganik, J.R.; Biomarkers of Aging, C.; Justice, J.; Belsky, D.W.; Higgins-Chen, A.; Moskalev, A.; Fuellen, G.; Cohen, A.A. , et al. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell 2023, 186, 3758–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohaisen, N.; Gittins, M.; Todd, C.; Sremanakova, J.; Sowerbutts, A.M.; Aldossari, A.; Almutairi, A.; Jones, D.; Burden, S. Prevalence of Undernutrition, Frailty and Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling People Aged 50 Years and Above: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msemburi, W.; Karlinsky, A.; Knutson, V.; Aleshin-Guendel, S.; Chatterji, S.; Wakefield, J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2023, 613, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNee, W.; Rabinovich, R.A.; Choudhury, G. Ageing and the border between health and disease. Eur Respir J 2014, 44, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soegiarto, G.; Purnomosari, D. Challenges in the Vaccination of the Elderly and Strategies for Improvement. Pathophysiology 2023, 30, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierala, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Meczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Moodie, E.M.; Forget, M.F.; Desmarais, P.; Keezer, M.R.; Wolfson, C. Health Heterogeneity in Older Adults: Exploration in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021, 69, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirato, G.R.; Borges, J.O.; Marques, D.L.; Santos, J.M.B.; Santos, C.A.F.; Andrade, M.S.; Furtado, G.E.; Rossi, M.; Luis, L.N.; Zambonatto, R.F. , et al. L-Glutamine Supplementation Enhances Strength and Power of Knee Muscles and Improves Glycemia Control and Plasma Redox Balance in Exercising Elderly Women. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaiou, R.D.; Herndler-Brandstetter, D.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B. Age-related changes in immunity: implications for vaccination in the elderly. Expert Rev Mol Med 2007, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A. Biology of aging: Paving the way for healthy aging. Exp Gerontol 2018, 107, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafe, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minciullo, P.L.; Catalano, A.; Mandraffino, G.; Casciaro, M.; Crucitti, A.; Maltese, G.; Morabito, N.; Lasco, A.; Gangemi, S.; Basile, G. Inflammaging and Anti-Inflammaging: The Role of Cytokines in Extreme Longevity. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2016, 64, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felismino, E.S.; Santos, J.M.B.; Rossi, M.; Santos, C.A.F.; Durigon, E.L.; Oliveira, D.B.L.; Thomazelli, L.M.; Monteiro, F.R.; Sperandio, A.; Apostolico, J.S. , et al. Better Response to Influenza Virus Vaccination in Physically Trained Older Adults Is Associated With Reductions of Cytomegalovirus-Specific Immunoglobulins as Well as Improvements in the Inflammatory and CD8(+) T-Cell Profiles. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 713763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Dupuis, G.; Le Page, A.; Frost, E.H.; Cohen, A.A.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunosenescence and Inflamm-Aging As Two Sides of the Same Coin: Friends or Foes? Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Dupuis, G.; Witkowski, J.M.; Larbi, A. The Role of Immunosenescence in the Development of Age-Related Diseases. Rev Invest Clin 2016, 68, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle-Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr Rev 2020, 41, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Calvani, R.; Tosato, M.; Landi, F.; Picca, A.; Marzetti, E. Protein intake and physical function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 81, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuzzi, L.G.; Rama, L.; Bishop, N.C.; Rosado, F.; Martinho, A.; Paiva, A.; Teixeira, A.M. Lifelong training improves anti-inflammatory environment and maintains the number of regulatory T cells in masters athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol 2017, 117, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, K.M.; Perkins, R.K.; Jemiolo, B.; Raue, U.; Trappe, S.W.; Trappe, T.A. Effects of aging and lifelong aerobic exercise on basal and exercise-induced inflammation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2020, 128, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.; Yung, R. Immune senescence, epigenetics and autoimmunity. Clin Immunol 2018, 196, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, G.S.; Galvao, L.L.; Tribess, S.; Meneguci, J.; Virtuoso Junior, J.S. Isotemporal substitution of sleep or sedentary behavior with physical activity in the context of frailty among older adults: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J 2023, 141, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, C.S.L.; Thang, L.A.N.; Maier, A.B. Markers of inflammation and their association with muscle strength and mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2020, 64, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, G.E.; Letieri, R.V.; Caldo-Silva, A.; Sardao, V.A.; Teixeira, A.M.; de Barros, M.P.; Vieira, R.P.; Bachi, A.L.L. Sustaining efficient immune functions with regular physical exercise in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Eur J Clin Invest 2021, 51, e13485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomari, M.A.; Khabour, O.F.; Alzoubi, K.H. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Amid Confinement: The BKSQ-COVID-19 Project. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2020, 13, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, U.R.; Couppe, C.; Karlsen, A.; Grosset, J.F.; Schjerling, P.; Mackey, A.L.; Klausen, H.H.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjaer, M. Life-long endurance exercise in humans: circulating levels of inflammatory markers and leg muscle size. Mech Ageing Dev 2013, 134, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, L.D.; Herbert, P.; Sculthorpe, N.F.; Grace, F.M. Short-Term and Lifelong Exercise Training Lowers Inflammatory Mediators in Older Men. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 702248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.J.; Park, S.K.; Jee, Y.S. Detraining Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Fitness, Cytokines, C-Reactive Protein and Immunocytes in Men of Various Age Groups. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.R.; Roseira, T.; Amaral, J.B.; Paixao, V.; Almeida, E.B.; Foster, R.; Sperandio, A.; Rossi, M.; Amirato, G.R.; Apostolico, J.S. , et al. Combined Exercise Training and l-Glutamine Supplementation Enhances Both Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses after Influenza Virus Vaccination in Elderly Subjects. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.A.F.; Amirato, G.R.; Jacinto, A.F.; Pedrosa, A.V.; Caldo-Silva, A.; Sampaio, A.R.; Pimenta, N.; Santos, J.M.B.; Pochini, A.; Bachi, A.L.L. Vertical Jump Tests: A Safe Instrument to Improve the Accuracy of the Functional Capacity Assessment in Robust Older Women. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Kader, S.M.; Al-Jiffri, O.H. Aerobic exercise modulates cytokine profile and sleep quality in elderly. Afr Health Sci 2019, 19, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.G.; Lima, T.A.; Macedo, L.A.; Sa, M.P.; Vidal Mde, L.; Gomes, A.F.; Oliveira, L.C.; Santos, A.M. Ethics in research with human beings: from knowledge to practice. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010, 95, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, C. Helsinki 50 years on. Clin Ter 2014, 165, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shephard, R.J. Ethics in exercise science research. Sports Med 2002, 32, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N.; Group, T. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health 2004, 94, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, B.; Rajappa, M.; Mallika, V.; Shukla, D.K.; Kumar, S. TNF-alpha/IL-10 ratio and C-reactive protein as markers of the inflammatory response in CAD-prone North Indian patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chim Acta 2009, 408, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L. , et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfein, A.J.; Herzog, A.R. Robust aging among the young-old, old-old, and oldest-old. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1995, 50, S77–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.A.F.; Amirato, G.R.; Paixão, V.; Almeida, E.B.; Do Amaral, J.B.; Monteiro, F.R.; Roseira, T.; Juliano, Y.; Novo, N.F.; Rossi, M. , et al. Association among inflammaging, body composition, physical activity, and physical function tests in physically active women. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, M.J.R.; Bertola, L.; Szlejf, C.; Oliveira, D.; Piovezan, R.D.; Cesari, M.; de Andrade, F.B.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Perracini, M.R.; Ferri, C.P. , et al. Validating intrinsic capacity to measure healthy aging in an upper middle-income country: Findings from the ELSI-Brazil. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022, 12, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blocquiaux, S.; Gorski, T.; Van Roie, E.; Ramaekers, M.; Van Thienen, R.; Nielens, H.; Delecluse, C.; De Bock, K.; Thomis, M. The effect of resistance training, detraining and retraining on muscle strength and power, myofibre size, satellite cells and myonuclei in older men. Exp Gerontol 2020, 133, 110860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijders, T.; Leenders, M.; de Groot, L.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Verdijk, L.B. Muscle mass and strength gains following 6 months of resistance type exercise training are only partly preserved within one year with autonomous exercise continuation in older adults. Exp Gerontol 2019, 121, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauretani, F.; Russo, C.R.; Bandinelli, S.; Bartali, B.; Cavazzini, C.; Di Iorio, A.; Corsi, A.M.; Rantanen, T.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2003, 95, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, C.; Mathiowetz, V. Reliability and validity of a novel instrument for the quantification of hand forces during a jar opening task. J Hand Ther 2022, 35, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, M.G.; de Lira, C.A.; Passos, G.S.; Santos, C.A.; Silva, A.H.; Yoshida, C.H.; Tufik, S.; de Mello, M.T. Is the six-minute walk test appropriate for detecting changes in cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy elderly men? J Sci Med Sport 2012, 15, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkendall, D.T.; Garrett, W.E., Jr. The effects of aging and training on skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med 1998, 26, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, T.; Aussieker, T.; Holwerda, A.; Parise, G.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Verdijk, L.B. The concept of skeletal muscle memory: Evidence from animal and human studies. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2020, 229, e13465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.D.; Rhea, M.R.; Sen, A.; Gordon, P.M. Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2010, 9, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; McCarthy, J.J.; Malakoutinia, F. Myonuclear permanence in skeletal muscle memory: a systematic review and meta-analysis of human and animal studies. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2276–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, C.V.; Ribeiro, I.S.; Galantini, M.P.L.; Muniz, I.P.R.; Lima, P.H.B.; Santos, G.S.; da Silva, R.A.A. Inflammaging and body composition: New insights in diabetic and hypertensive elderly men. Exp Gerontol 2022, 170, 112005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Singh, H.; Kwon, K.; Tsitrin, T.; Petrini, J.; Nelson, K.E.; Pieper, R. Protein signatures from blood plasma and urine suggest changes in vascular function and IL-12 signaling in elderly with a history of chronic diseases compared with an age-matched healthy cohort. Geroscience 2021, 43, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K. Chronic Inflammation as an Immunological Abnormality and Effectiveness of Exercise. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachi, A.L.; Suguri, V.M.; Ramos, L.R.; Mariano, M.; Vaisberg, M.; Lopes, J.D. Increased production of autoantibodies and specific antibodies in response to influenza virus vaccination in physically active older individuals. Results Immunol 2013, 3, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Peruta, C.; Lozanoska-Ochser, B.; Renzini, A.; Moresi, V.; Sanchez Riera, C.; Bouche, M.; Coletti, D. Sex Differences in Inflammation and Muscle Wasting in Aging and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Pawelec, G.; Khalil, A.; Cohen, A.A.; Hirokawa, K.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunology of Aging: the Birth of Inflammaging. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2023, 64, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Volunteer Groups | |||||||

| Older women (n=18) | p-values | Older men (n=7) | p-values | |||||

| PRE | POST | POST-TR | PRE | POST | POST-TR | |||

| Age (years) | 75.2±7.0* | 76.2±7.0 | 77.1±7.1† | *†<0.001 | 72.4±7.1* | 73.4±7.1 | 75.1±7.1† | *†<0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.32±14.5 | 59.78±14.23 | 59.58±14.11 | 0.534 | 70.69±9.14 | 67.61±10.79 | 70.96±8.71 | 0.312 |

| Height (m) | 1.53±0.07 | 1.53±0.07 | 1.53±0.07 | 0.955 | 1.68±0.08 | 1.68±0.08 | 1.68±0.08 | 0.915 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.32±4.21 | 24.14±4.46 | 24.29±4.16 | 0.694 | 24.82±3.29 | 23.59±2.05 | 25.30±2.98 | 0.401 |

| GS (m/s) | 0.97±0.21* | 0.81±0.25 | 0.99±0.18† |

*0.009 †0.015 |

1.03±0.15 | 1.06±0.18 | 1.02±0.19 | 0.914 |

| TUG (s) | 6.8±1.0* | 7.3±1.2 | 7.1±0.8 | *0.033 | 6.0±0.5 | 6.1±0.4 | 6.3±0.6 | 0.707 |

| HG (kgf) | 23.1±3.7# | 21.3±4.5 | 20.7±3.6 | #0.005 | 37.6±5.9*,# | 33.6±7.5 | 33.8±7.4 |

*0.008 #0.019 |

| Older women group (n=18) | ||||||||

| Parameters | 2019 (PRE) | Parameters | 2021 (POST) | Parameters | 2022 (POST-TR) | |||

| rho-value | p-value | rho-value | p-value | rho-value | p-value | |||

| BMI X TUG | 0.60 | 0.009 | BMI X TUG | 0.65 | 0.009 | BMI X TUG | 0.53 | 0.025 |

| Age X GS | —0.56 | 0.016 | GS X TUG | - 0.63 | 0.012 | GS X TUG | - 0.54 | 0.020 |

| Age X IL-12p70/IL-10 | 0.58 | 0.012 | GS X IL-8/IL-10 | - 0.51 | 0.044 | BMI X TNF-α | 0.48 | 0.045 |

| GS X IL-12p70/IL-10 | - 0.57 | 0.014 | TUG X IL-8 | 0.55 | 0.034 | Age X IL-6 | 0.53 | 0.023 |

| GS X IL-10 | 0.50 | 0.036 | HG X IL-10 | 0.49 | 0.041 | Age X IL-12p70 | 0.49 | 0.038 |

| IL-6 X IL-10 | 0.99 | <0.001 | HG X IL-12p70 | - 0.51 | 0.030 | Age X IL-12p70/IL-10 | 0.48 | 0.044 |

| IL-6 X IL-12p70 | 0.99 | <0.001 | HG X IL-12p70/IL-10 | - 0.51 | 0.032 | IL-6 X IL-10 | 0.77 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 X TNF-α | 0.99 | <0.001 | HG X IL-8/IL-10 | - 0.56 | 0.016 | IL-6 X IL-12p70 | 0.58 | 0.011 |

| IL-6 X IFN-γ | 0.91 | <0.001 | IL-6 X IL-10 | 0.81 | <0.001 | IL-10 X IL-12p70 | 0.70 | 0.001 |

| IL-10 X IL-12p70 | 0.99 | <0.001 | IL-6 X IL-12p70 | 0.82 | <0.001 | |||

| IL-10 X TNF-α | 0.99 | <0.001 | IL-10 X IL-12p70 | 0.99 | <0.001 | |||

| IL-10 X IFN-γ | 0.91 | <0.001 | IL-8 X TNF-α | 0.64 | 0.004 | |||

| IL-12p70 X TNF-α | 0.99 | <0.001 | IL-8 X IFN-γ | 0.59 | 0.011 | |||

| IL-12p70 X IFN-γ | 0.90 | <0.001 | TNF-α X IFN-γ | 0.86 | <0.001 | |||

| Older men group (n=7) | ||||||||

| Parameters | 2019 (PRE) | Parameters | 2021 (POST) | Parameters | 2022 (POST-TR) | |||

| rho-value | p-value | rho-value | p-value | rho-value | p-value | |||

| GS X IFN-γ | - 0.78 | 0.049 | Age X TUG | 0.81 | 0.029 | BMI X IL-6 | 0.76 | 0.049 |

| TUG X IL-10 | - 0.79 | 0.048 | HG X TNF- α | - 0.79 | 0.048 | TUG X IL-10 | - 0.87 | 0.010 |

| IL-6 X IL-10 | 0.96 | 0.003 | IL-10 X IL-12p70 | 0.95 | <0.001 | TUG X IL-8 | 0.81 | 0.027 |

| IL-6 X IL-12p70 | 0.86 | 0.024 | IL-10 X IFN-γ | 0.90 | 0.006 | HG X TNF-α | - 0.79 | 0.033 |

| IL-8 X IL-10 | 0.79 | 0.048 | IL-12p70 X IFN-γ | 0.93 | 0.002 | HG X IFN-γ | - 0.83 | 0.022 |

| IL-10 X TNF-α | 0.86 | 0.024 | TNF-α X IFN-γ | 0.85 | 0.016 | IL-8 X IL-10 | 0.80 | 0.032 |

| IL-8 X TNF-α | 0.77 | 0.041 | ||||||

| IL-10 X TNF-α | 0.79 | 0.035 | ||||||

| TNF-α X IFN-γ | 0.85 | 0.015 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).