1. Introduction

Aquatic ecosystems are indisputably the most vulnerable infrastructure of every nation in the world. Their high-level vulnerability stems from their root state as they exist in the environment, which is affected by climatic properties, their intensity, and in recent centuries also by anthropogenic factors caused by human activities [

1,

2]. If one has no means and no influence on the course of natural events in the climate sector, they can at least carry out an analysis of these events using suitable mathematical methods [

3,

4] and take necessary measures to mitigate the negative impacts on aquatic ecosystems, at the minimum in the following areas:

Treating/handling rainwater.

Artificial retention of surface water in the landscape

Protection of groundwater and surface water from contamination

Monitoring contamination and risk assessment.

Solution of contamination using progressive engineering methods.

Maintaining long-term sustainability of aquatic ecosystems in a state of positive balance.

Achieving the above mentioned state is economically expensive especially in industrial zones and regions where the water contamination is currently beyond the threshold. It is vital to intensively deal with environmental quality of agroecosystems by means of monitoring individual detected outputs [

5]. Attention is to be drawn to the increasing threat of contamination caused by plastics and compounds, which disrupt the endocrine system, by heavy metals in water and by other biological and chemical substances used in the engineering infrastructure of the given region [

6,

7]. The Czech Republic is well-known for not owning a significant source of flowing water for water resource management purposes nor a source suitable for power supply and other technical and operational uses. The country is entirely dependent on snow and rain precipitations and their intensity.

Adverse processes that limit, pollute, and transform water resources can generally be either natural or anthropogenic, or a combination of both [

8,

9,

10,

11]. These serious causes include processes that negatively affect climate change by their behavior, such as the tilt of the Earth's axis, the intensity of solar radiation, changes in plate tectonics and volcanic eruptions, increasing concentrations of greenhouse gasses, and the shrinking of land, shelf and mountain glaciers. , sea level rise etc. [

12] and secondarily they can cause pollution of water resources. spatial and temporal distribution of water resources. As a result, water resources are not evenly distributed around the world [

13]. For example, purely human causes include a growing world population [

14], which brings with it an increasing rate of urbanization [

15] and an increasing number of developed areas around the world. Two negative trends are closely related to these causes. The first is called Urban Sprawl [

16], when commercial, logistic, industrial and other enterprises spread over the cities on the so-called green field, and the second is called Urban Sealing, where all types of buildings lead to the transformation of natural permeable surfaces into impermeable surfaces [

17]. Last but not least, we must also include in this list the growing commercial deforestation and global pollution of the environment, with which the pollution of the world's oceans [

18,

19] and rivers [

20,

21,

22]. These can be the only source of drinking water in many countries and, if polluted, can limit the life of the local society.

Climatic changes may increase the risk of aquatic ecosystems contamination in various ways [

23]. Some of the main threats of aquatic ecosystems contamination in new climatic conditions include:

Precipitation Changes: Extreme precipitations may lead to floods, which wash polluting substances down from the landscapes into water bodies and reservoirs. On the contrary, a long-term drought may cause accumulation of polluting substances in surface waters as the precipitation shortage decreases waterflow, which slows down their diluting and washing away.

Rising Water Temperatures: Higher water temperatures may increase the risk of toxic algae and cyanobacteria growth, which produce toxins known as cyanotoxins. These substances may threaten the health of aquatic organisms as well as people that come in contact with them.

Changes in the Volume of Glaciers and Snow: Melting glaciers and snow may release pollutants accumulated over the long-term such as heavy metals and persistent organic substances, which may contaminate bodies of water and reservoirs.

Increased Frequency of Extreme Events: Increased frequency of extreme events, such as storms and floods, may cause the release of hazardous chemicals from industrial facilities and warehouses into aquatic ecosystems.

Acidity of Oceans: Ocean acidification may influence chemical processes which affect the availability and toxicity of certain substances in aquatic ecosystems. This may have an indirect impact on the health of aquatic organisms.

Changes in Soil Use: Changes in the use of soil as a result of climatic changes such as agricultural expansion or mining may increase the risk of pesticides, fertilizers and other pollutants seeping out into aquatic ecosystems.

Scientific literature is concerned with ecosystem improvement. Authors define how the use of sustainable procedures has led to the increase of implementation of green technologies and nature-friendly solutions [

24]. Based on the research, the range of options used to improve the environmental health of urban spaces is being solved. The analysis revealed that cases using an integrated approach to the solution show high ambitions. Nature-friendly solutions, especially green technologies, appear to be attractive tools which might help improve the current situation [

25]. Research, which proved that nature-friendly measures mitigate and solve the depletion of sources and climate problems, came to similar results [

26].

Other topics considered include rainwater management and a focus on urban resistance including international relations [

27,

28]. Attention is paid to the scope of resilience of urban rainwater drainage systems, which the authors describe. There are other solutions for managing rainwater [

29]. Significant parts of water sources have been polluted in recent years, especially those near cities and industrial agglomerations. Therefore, the monitoring of water bodies and the subsequent assessment of possible risks rises in importance. This problem is being solved and, simultaneously, the need of using new and economically more effective monitoring methods used to check the decrease of polluting sources is emphasized [

30]. A major segment is the sustainability of aquatic ecosystems, where tools, indicators, and approaches currently used in the field of aquatic ecosystems and their potential contamination play an important role [

31]. An integral part is the assessment of ecosystem services, which is gaining much more importance in sustainable and ecological development [

32].

The purpose of this study is to understand specific aspects of contamination threats of drinking water sources and determine possible solutions in order to eliminate the risk, shown in the example case study in the Czech Republic conditions.

Research questions were stated as follows:

- a)

What is the approach when handling snow and rain precipitations?

- b)

How is the surface and groundwater protection against contamination implemented?

- c)

What is the approach regarding contamination prevention and maintaining a long-term sustainability of aquatic ecosystems?

2. Materials and Methods

Several major threats of aquatic ecosystem contamination may be identified in the Czech Republic. These threats are associated with various human activities and environmental factors.

An overview of the threats is described in

Table 1.

The study is written in the form of a case study using a detailed research approach aimed at the examination of a particular case - contamination threats of drinking water sources and prevention enhancement of their protection under Czech conditions. In the case study, the particular cases and pollution threat conditions are analyzed from different points of view. The case study is compiled based on the collection and analysis of data. The aim of the case study is to understand specific aspects of contamination threats of drinking water sources, prevention enhancement of their protection under Czech conditions, and to gain deeper knowledge which might be used to solve problems or to develop theoretical concepts. The case study is used to illustrate particular principles, strategies and approaches in practice and works as a useful tool for the demonstration of particular concepts and approaches.

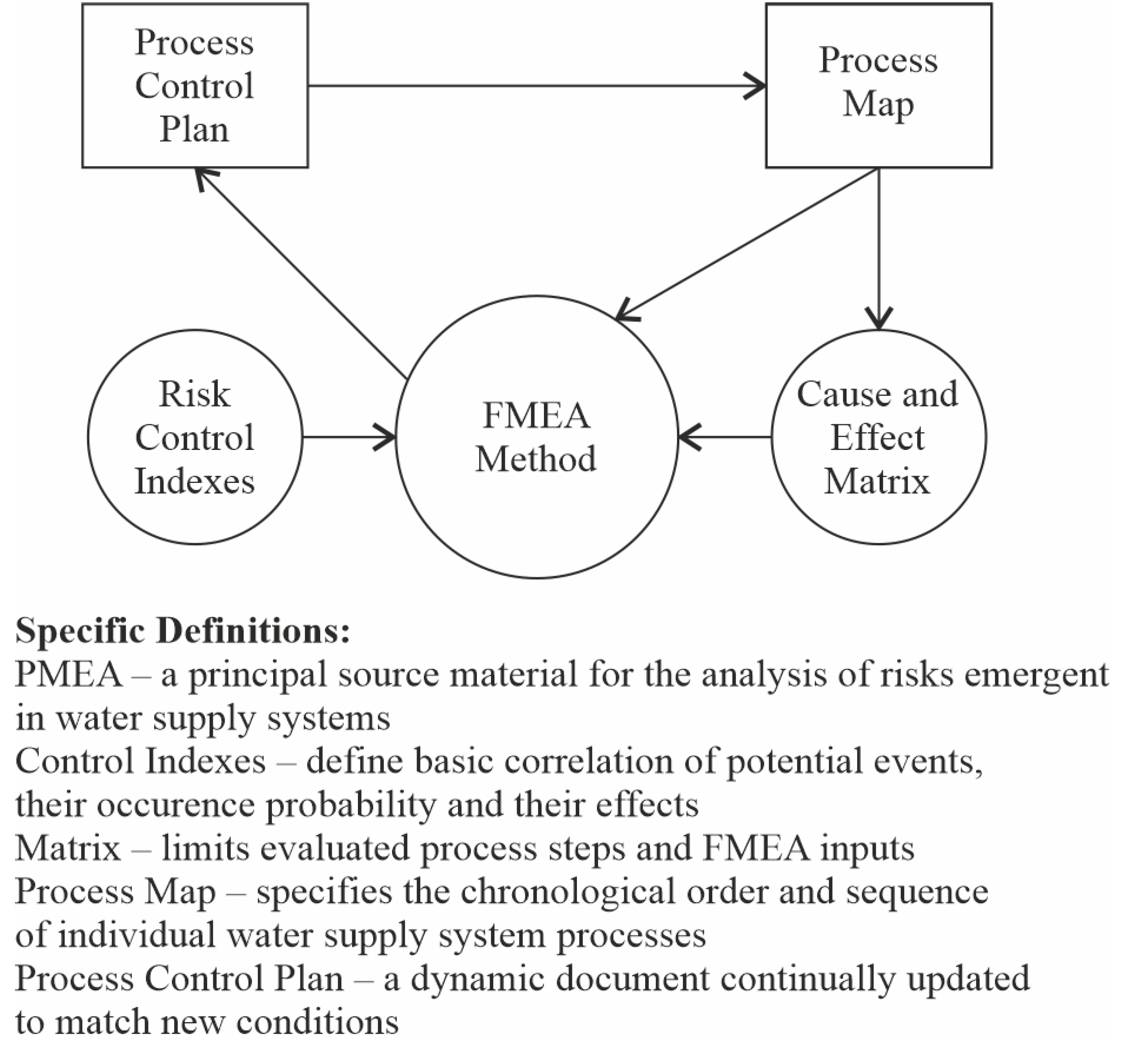

FMEA - Failure Mode and Effects Analysis method serves partially as a support tool. It is an analytical method focusing on the identification of possible defect occurrence points. FMEA method is to be treated as a living document, which needs to be updated regularly. The risks and the efficiency of determined measures of their elimination are to be assessed regularly as well [

33].

In order to meet the objective and to develop the basis for the research question, a systematic approach of literature search was used to obtain current information sources, published results and information in the field of threats of pollution of drinking water sources and prevention of increasing their protection. Furthermore, the method of analysis and synthesis was used, i.e. breaking down the whole into sub-components and combining the individual information into a whole, describing the principles in interdependencies. The above procedure was used in the analysis of the actual information and especially in its synthesis in the final part of the research. Another method used to elaborate the research objective was deduction, a process of reasoning from premises, where a conclusion is reached by proof. The procedure was applied in the elaboration of the findings of the empirical investigation into the summary final part of the research.

3. Results

3.1. Handling Snow and Rain Precipitations

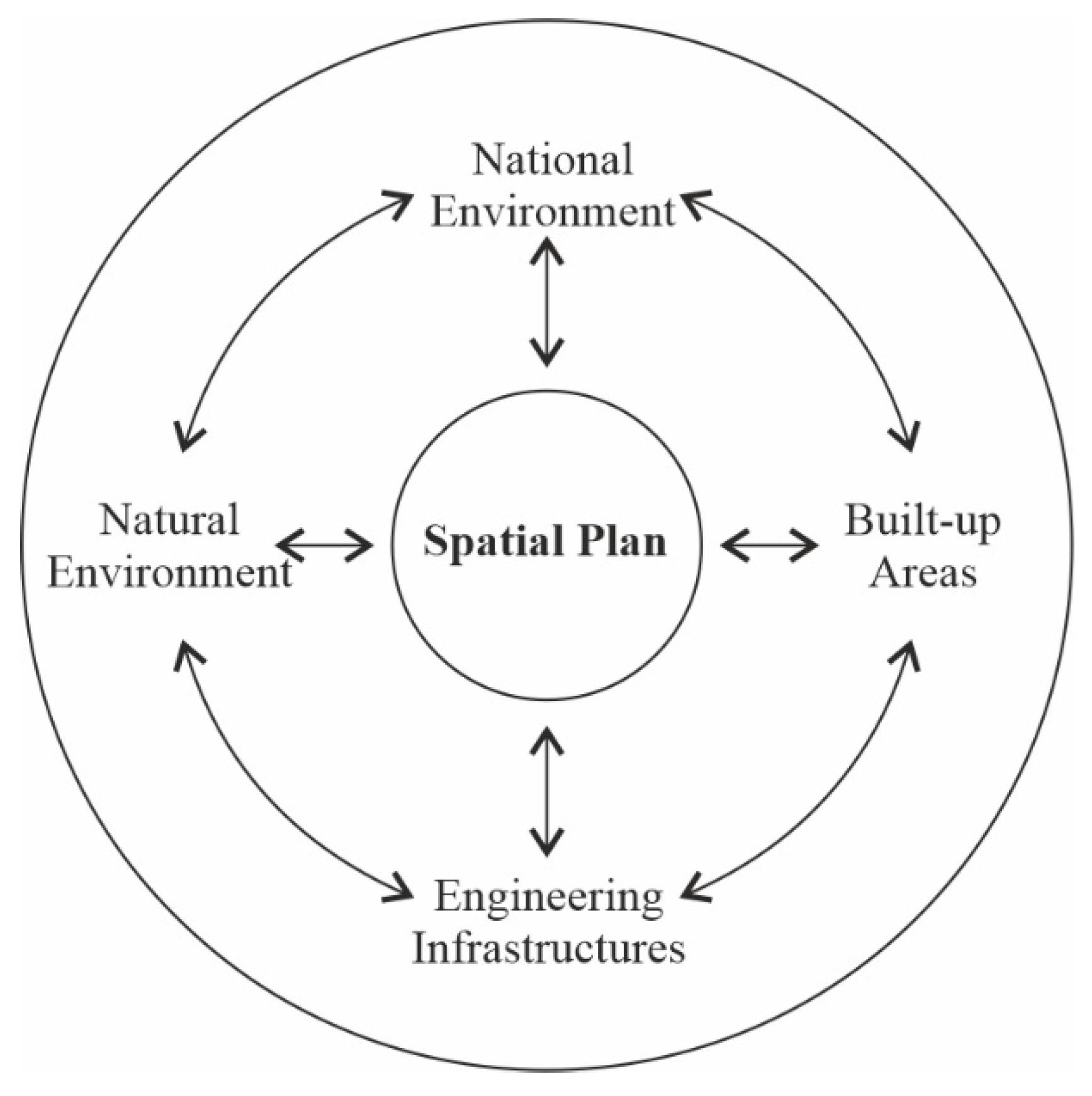

A spatial plan, see

Figure 1, carries an exceptional importance in terms of a long-term sustainability of aquatic ecosystem function under set and constant conditions.

A spatial plan, developed optimally and for a long-term scope, is the prime protection of a region from alternative negative secondary impacts of water, soil, air pollution and other influences on the health of people, fauna, and flora caused by the burden of technological development [

34]. With the relatively small size of the Czech Republic, its high traffic and engineering infrastructure density, and a high number of logistics and business zones, the spatial plan is to fulfill the regulation role in terms of preserving enough free space for the long-term sustainability of the unspoilt natural environment with minimal influences and risks of contamination by undesirable substances, including the precipitation intensity and occurrence in individual regions of the Czech Republic and the risk analysis after a significant change, as a consequence of climatic change in Central Europe.

While assessing the risks resulting from a potential lack of drinking water in the Czech Republic or any other region, in order to optimize the process, it is desirable to carry out a balance sheet regarding the total water supply in the site of origin, time imbalance, and their continual renewal in terms of the Earth’s water cycle in the primary part of the analytical analysis. It is crucial to keep in mind that the Czech Republic is 100% reliant on rainwater. The goal of every water manager has to be an effort made to retain the surface runoff of the Czech region for the longest time period possible so that it improves the water infiltration process and thus strengthens the groundwater repositories. The water management tendencies in the second half of the 20th century were exactly contrary. A nationwide regulation of recipients with the aim of quick water drainage from the Czech Republic was taking place regardless of the fact that the area is a geographical “roof of Europe”. Therefore, it is a strategic necessity to retain water in water reservoirs, especially in the relief, to the utmost extent.

Precipitations are the product of condensation or desublimation of water vapour in the air or on the land surface. The average precipitation height in a drainage basin is expressed by the thickness of the water layer from rainfall per a set time period. It is expressed in mm and is defined as follows [

9]:

where

Hs- average precipitation height in a drainage basin [mm]

F - surface area of the drainage basin [km2]

k = 10 -3 - coefficient

S - total precipitation volume [m3]

Because the Czech Republic has no other continual source of water renewal but rainwater, it is important to minimize the range of its direct surface runoff and thus achieve a point where the runoff occurs mainly in rain-free periods. As groundwater is recharged by the process of infiltration, it is appropriate to make favourable conditions in built-up areas by either natural or artificial infiltration even at increased investment costs.

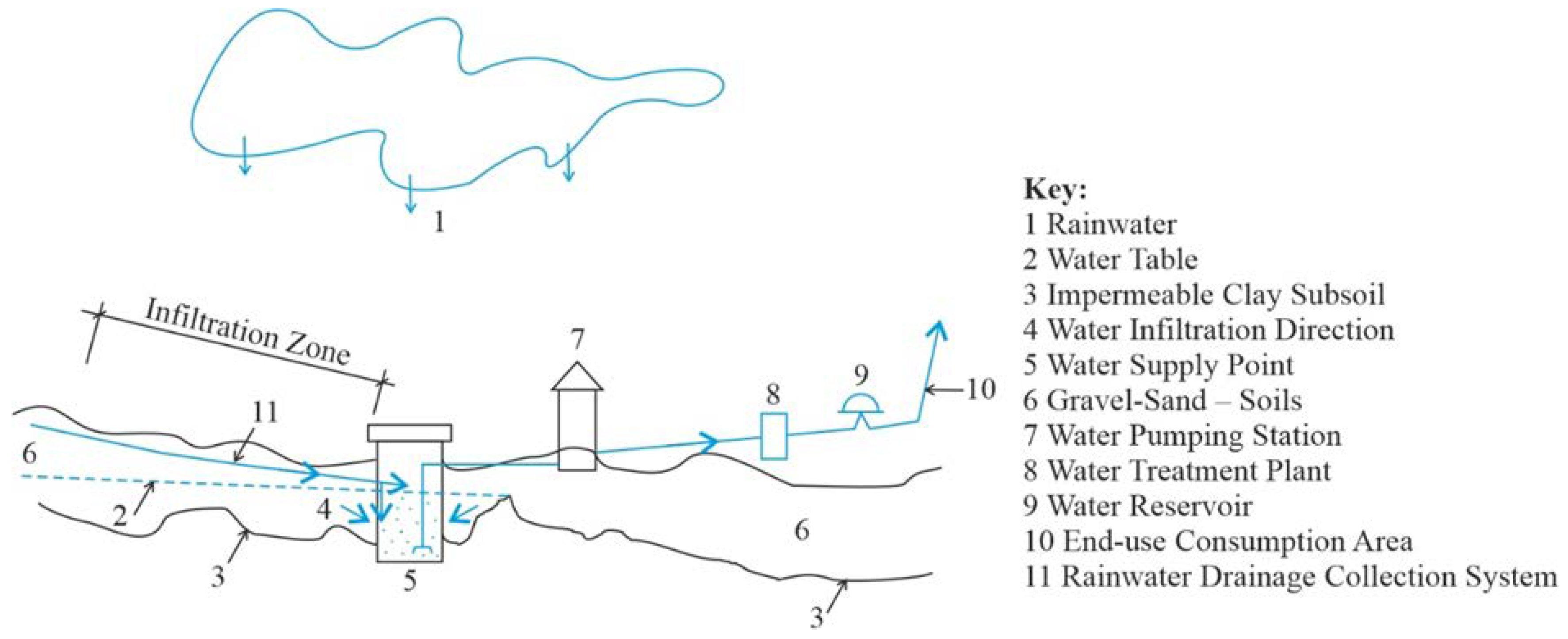

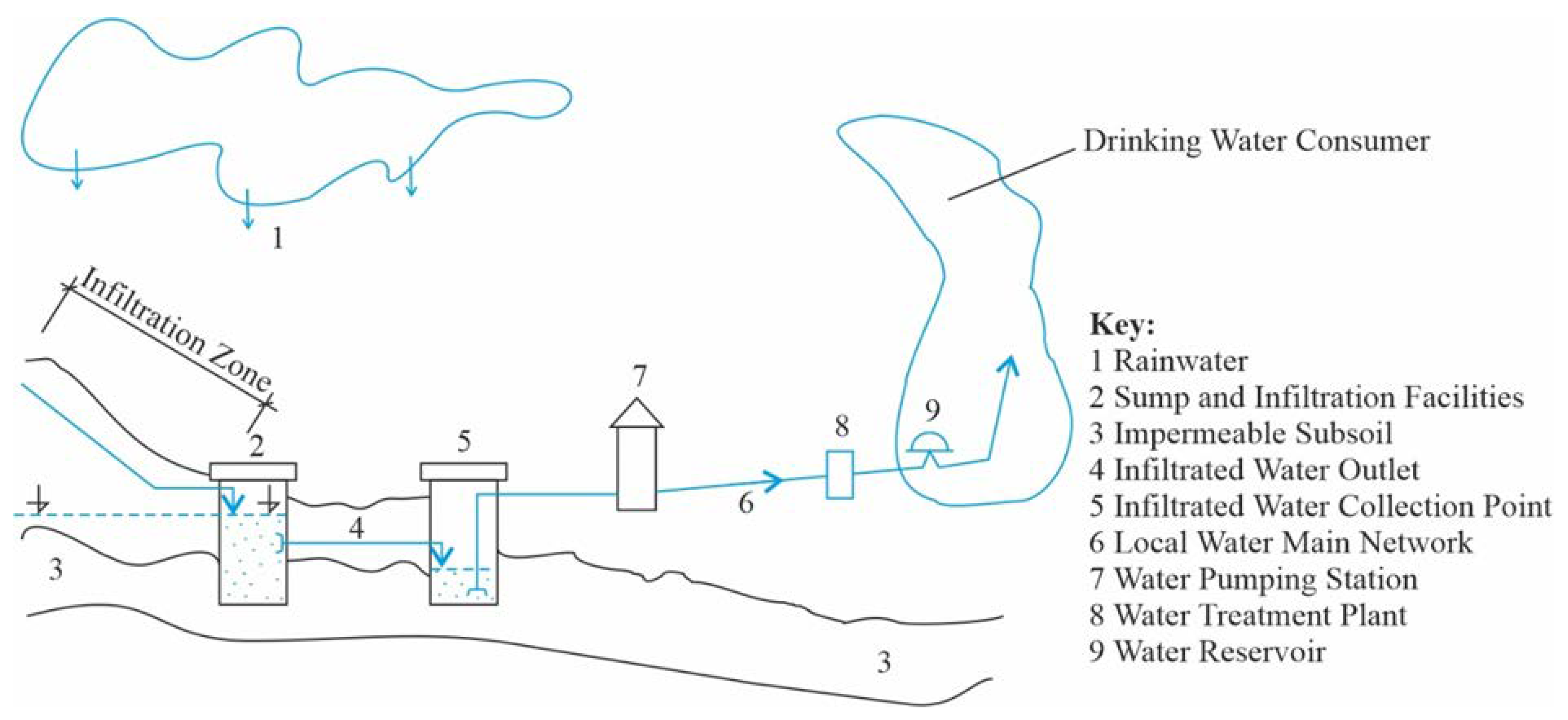

As shown in Figure. 2, a spatial plan in a water management area creates conditions for the construction of artificial surface water reservoirs, which may be used secondarily for supplying the population with drinking water even in regions lacking enough groundwater for given purposes.

Due to the relatively fast-changing climatic conditions in the world, the primary natural water cycle will no longer be sufficient in relation to the needs of the engineering infrastructure of individual countries. A number of regions have already been affected by recurrent meteorological and subsequent hydrological droughts. Therefore, it will be crucial to take a wide range of costly precautionary measures in the field of aquatic ecosystems.

Some of the measures might be the steps listed below:

- 1.

artificial water infiltration into aquiferous layers;

- 2.

artificial infiltration of surface water into groundwater;

- 3.

construction of new water reservoirs.

The above mentioned basic ways of water volume growth intended for water supply management purposes can be implemented mainly through the means of two basic forms and ways of infiltrated water utilization. The whole process is depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

Both above shown variants follow the same goal in practice, i.e., to improve the rainfall utilization not only for water supply management purposes but now also in the field of general precipitation management in every country of the world.

Increased attention has been paid to the issue of rainwater retention in the Czech Republic for some time, especially due to the lack of other ways of providing high quality supplies of raw water suitable for its processing into drinking water. The methods shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 especially include the construction of water reservoirs with high degree of protection from secondary contamination through the creation of water source protection zones. The primary options of achieving the specified protection are mentioned in the following chapter.

3.2. Protection of Surface Water and Groundwater from Contamination

As indicated in the previous chapters, the danger of contamination of surface water as well as groundwater is increasing. The cause of this situation is the development of human knowledge and the usage of new materials and technologies of their processing with deficiencies in the field of prevention; as well as the relatively frequent occurrence of new accidents caused by old ecological burdens which arise from the use of the original technological materials beyond their service time on the time axis of their service life [

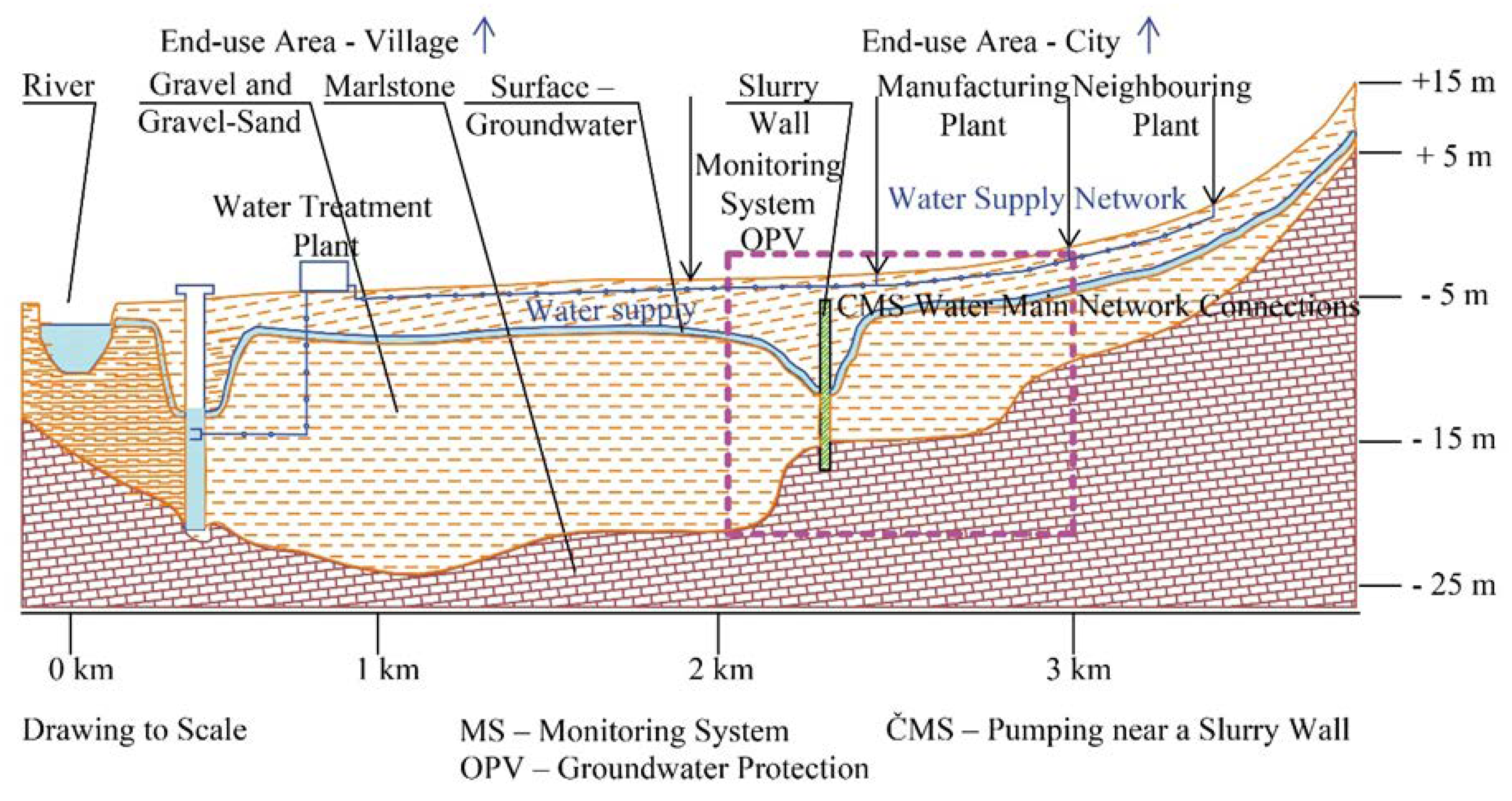

35]. The most dangerous types of old ecological burdens are caused by unregistered dumps of chemical substances in industrial agglomerations after the end of service life of the original chemical substance containers and the subsequent contamination of soil layers and groundwater. In fact, the only feasible protection is the construction of a slurry wall around the entire source of contamination, see

Figure 5, with diligent monitoring of contaminated waters and observing hydraulic conditions in the wider area around the place of environment contamination.

One of the most serious problems concerning surface water and groundwater throughout the whole 21st century will be the change of dilution ratio of these waters as a consequence of ongoing global climatic change. The already high environmental material burden of aquatic ecosystems caused by noxious and hazardous substances will obviously be rising in the future. This poses a threat not only to the current fauna and flora but also to the surface and ground sources of drinking water.

Under the conditions of European Union countries, it is not possible to utilize any raw water but only the water which meets the requirements stated in the EU Council Directives No. 75/440 EEC regarding the quality of surface water used for drinking water abstraction (the directive lost its effect in 2007) [

36], the Directive of the EU Parliament and Council 2000/60/ES from 23 October 2000, which sets the scope for Community water policy [

37] and the EU Council Directive No. 79/869 EEC regarding the methods of measuring and abstraction frequency of surface water [

38]. From the above stated, it is apparent that maintaining the quality of raw water in aquatic ecosystems within the threshold values in categories A1, A2, A3, specifying the determination of the average index of water treatability in water supply management processes and ways of their technological processing into drinking water, will be continuously more demanding.

The Czech Republic has been fulfilling the required criteria for decades and permanently focuses on the long-term sustainability of this situation. Not only the sufficient legislative environment but also the advanced infrastructure and monitoring systems, which are able to issue a warning of impending danger in time, help to achieve this aim. Even with these successes achieved in the Czech Republic, a lasting task is to improve the current systems in accordance with new scientific knowledge in this field and the technological inventions in the field of monitoring technologies.

3.3. Prevention of Pollution and Maintaining Long-Term Sustainability of Aquatic Ecosystems

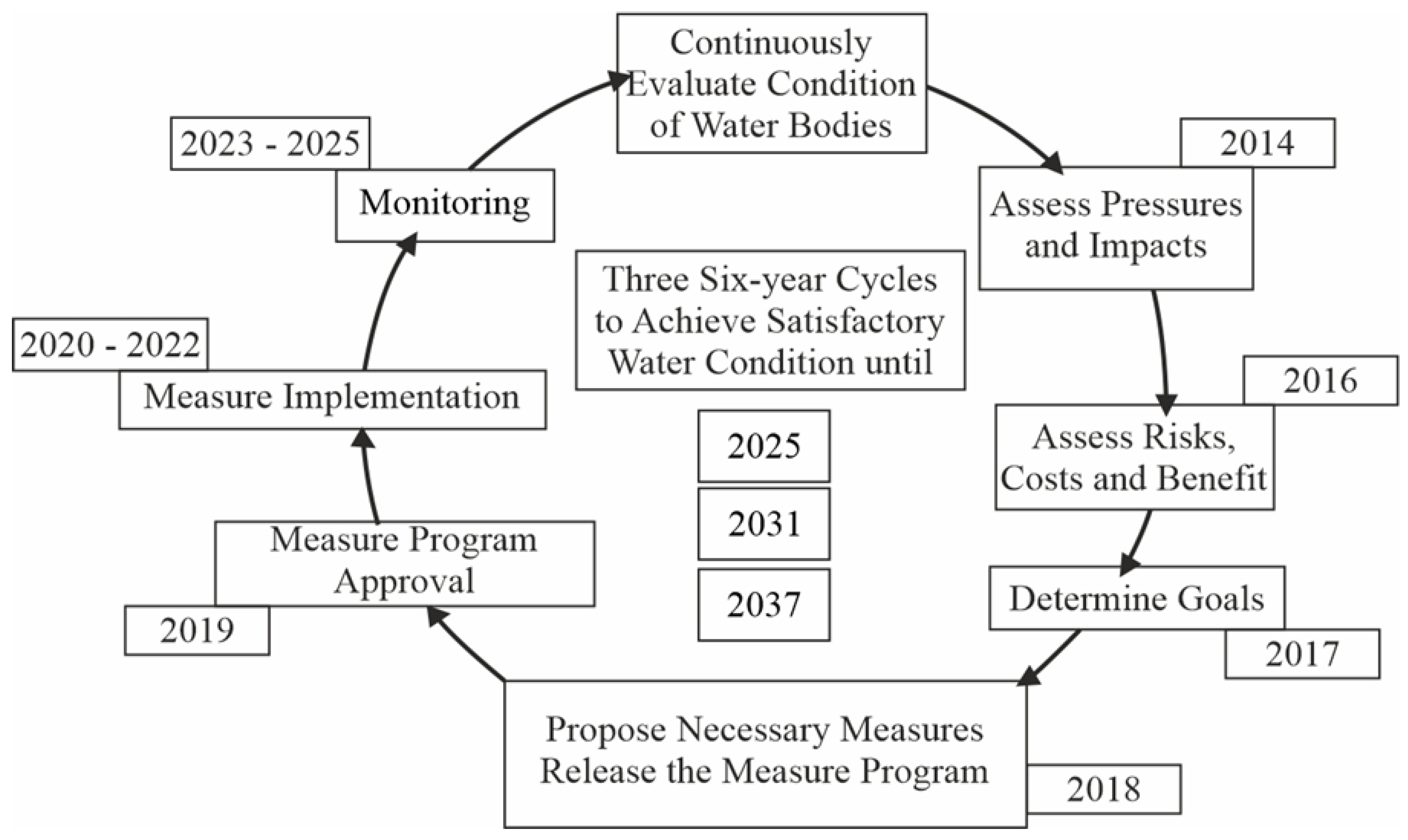

The Natural environment and aquatic ecosystems do not have or respect any artificial boundaries of regions and states. When tackling these issues, for example in water resource management, it is essential to consider Europe as one hydrological unit and to solve its issues as shown in

Figure 6.

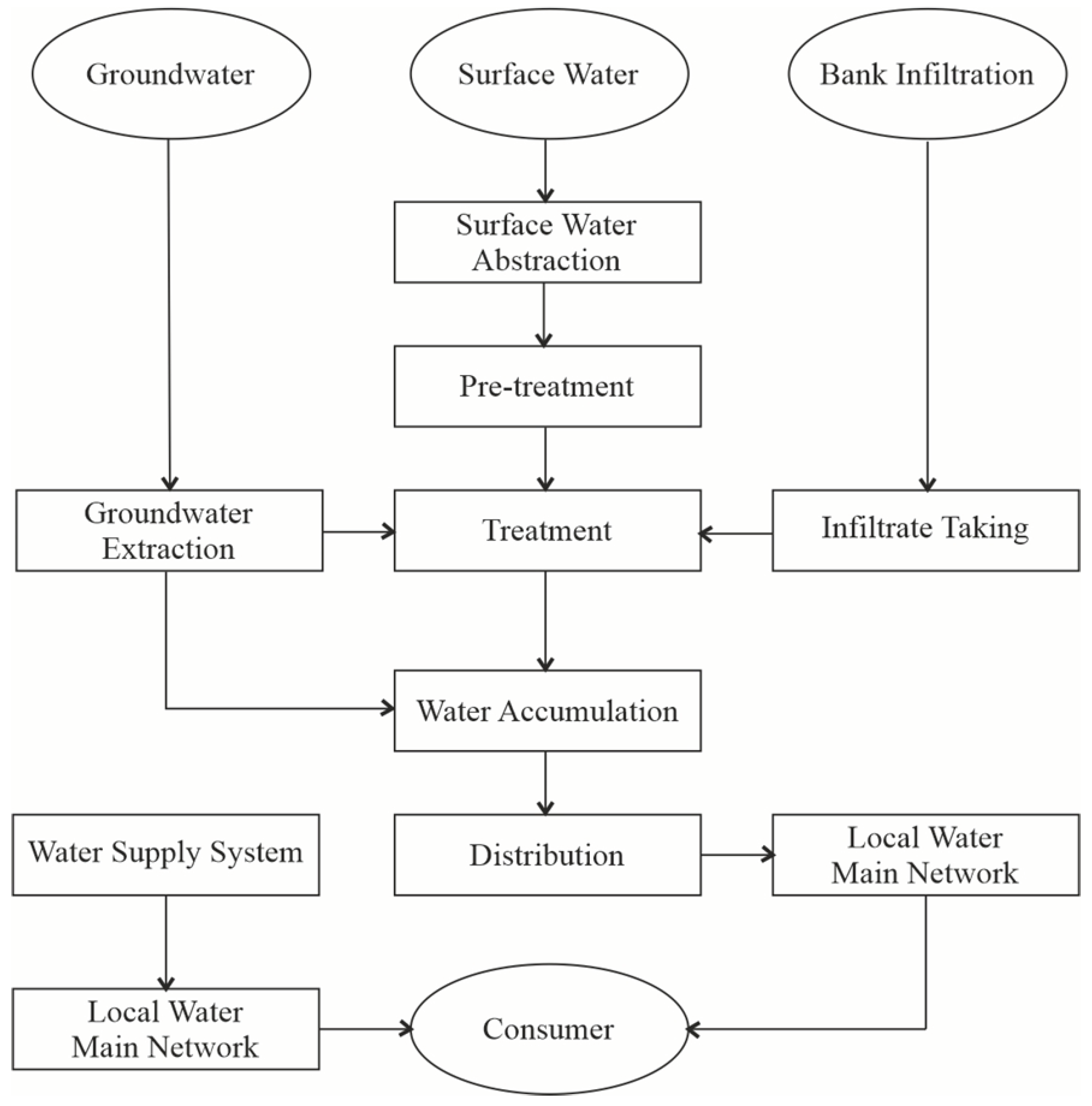

Waters and water environments cannot be efficiently protected when segmented, in individual countries, but only globally. The smallest unit of efficient protection is the drainage basin in question. The way of aquatic ecosystem protection in European Union countries is based on the previous statement. The previous figure is a simplified illustration of how to achieve the required protection. In the strict sense of the word, the waters used in the treatment process for turning them into drinking, utility and other technological waters are depicted in

Figure 7.

The complexity of water treatment processing it into drinking or technological water always depends on the purity of the water abstracted from an underground or surface source. When dealing with threatened aquatic ecosystems or those with already contaminated aquiferous soil layers, it is essential to prepare for a solution by using suitable methods. It is optimal for these systems to use the FMEA (Failure Mode and Effect Analysis) method and the control index method, which create sufficient space for an analysis.

Figure 8.

Mutual connections of operational risks and relations in risk analysis /authors.

Figure 8.

Mutual connections of operational risks and relations in risk analysis /authors.

The FMEA method, when appropriately used, has two primary goals, in which the following questions are to be answered:

Finding a structured way to the goal

identification of ways in which the analysis may fail completely or partially,

estimation of risks of particular cause of specified failure,

determination of priorities leading to goal achievement, which may decrease the danger of failure,

elaboration of a control plan which enables systematic avoidance of errors in the solving project.

The achievement of the determined goal is significantly supported by respecting the above described basic stimuli, and possibly other aspects, in relation to the solution scope. At this point, it also indicates what the purpose of seeking this way is.

Purpose of seeking this way:

the purpose of the used FMEA method is the identification of possible failure regarding the issues in question within operational conditions and the analysis of their effect relevancy,

defining mutual dependencies,

ordering of alternative errors,

precautionary measures against error occurrence.

If needed, the FMEA method includes the elaboration of a cause and effect matrix, which is preceded by risk control indexes of the environment or aquatic ecosystem in question. One of the important aspects of the issue in question is its simplicity and understandability. It is essential to presume the fact that the unintelligibility of the control plan and other measures generally leads not only to its misunderstanding, but at the same time it decreases the expected outputs of the entire solution of the issues in question.

A wide range of methods is used for analyses and solutions of issues in question in the Czech Republic. The use of a particular method or the development of a new one always depends on the conditions and the kind of aquatic ecosystem, its inclusion into the wider scope of environmental protection in a given drainage basin, as well as the possibilities of practical implementation. The most complex cases are in former industrial agglomerations of chemical and power system fields. What makes the conditions in the Czech Republic complicated is the current lack of surface water suitable for its treatment turning it into drinkable water while maintaining at least a basic balance between the outtake and the sources of water from rain and snow precipitations.

4. Discussion

Worldwide pollution of aquatic ecosystems has been gradually increasing for centuries. It cannot be assumed that there will be some change in the tendency threatening the original nature balance [

39] without using effective countermeasures. A positive value in this field seems to be the possibility to efficiently resist the set tendencies with the help of the latest scientific knowledge in the fields of chemistry, material engineering, and safety engineering.

The climatic conditions of individual states or regions are not an unchanging quantity - they tend to change over time from natural, and currently also anthropogenic causes. Since the beginning of the 21st century, one of these changes has been taking place worldwide, which, among other things, will also affect the aquatic ecosystems of the Czech [

40,

41]. Development trends suggest that natural volumes of surface and groundwater are most likely to be significantly reduced in the coming years and decades. In many regions in the Czech Republic, smaller recipients of watercourses and groundwater reserves will be significantly endangered [

42]. If artificial water accumulations can be operatively managed and adequately replenished depending on snow and rainfall, then running water and groundwater will be at risk of at least a periodic shortage. This is concurrent with the need to observe sufficient protection against pollution and increasing the concentration of dangerous substances in water and in the entire field of water resource management. However, a large part of this type of aquatic ecosystem is used for water supply purposes and for fire safety of an area, and in many cases as the only source of fire water.

Modern science and scientific knowledge of processes and their interconnection enable us not only to study the positive and negative aspects of natural processes, but also to mitigate negative impacts on the environment using the appropriately selected methods. In view of the fact that aquatic ecosystems are one of the most important aspects of all processes on Earth, it is essential to pay them maximum attention not only in scientific circles, but also among experts and the public globally. With the global drought, which is already affecting a third of the world’s populated areas, every further deterioration of the current situation is a serious warning, which must not be underestimated or ignored. One of the essential steps is threat assessment.

Threat assessment of aquatic ecosystem contamination is a complex process [

43,

44] which requires the integration of various factors and methodologies. The key steps and factors which should be included while assessing threats are as follows:

Identification of potential contaminators: Identification of pollution sources, such as industrial plants, agriculture, municipal sewage waters, surface runoff from urbanized areas etc., is the crucial first step. This also includes the identification of chemicals and substances which may be released into aquatic ecosystems.

The determination of target ecological and human values: The determination of values we want to protect, such as the biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems, quality of water intended for drinking, recreation and other economic or social uses, is essential for assessing the importance of contamination threats.

Exposition analysis: An assessment of how aquatic ecosystems are exposed to various types of pollution including the quantification of the amount and type of the pollutants entering them and their frequency.

Ecosystem sensitivity assessment: The evaluation of the sensitivity of aquatic ecosystems to various types of pollution and their reaction to contamination. This may include studies on the effect of pollution on biodiversity, ecosystem functions, and health of aquatic organisms population.

Risk Assessment: The combination of the exposition and sensitivity of ecosystems allows to assess the risk of aquatic ecosystems contamination. This includes the evaluation of the risk occurrence probability and the severity of its impacts on ecological and human values.

Planning of measures: Based on the risk assessment it is necessary to work out the plans for decreasing the risk of contamination and the protection of aquatic ecosystems. This may include measures taken to check and regulate the contamination sources, to improve the infrastructure for waste management, to monitor the quality of water and to implement the measures for climate change adaptation.

While assessing the threats of aquatic ecosystems contamination, the above mentioned steps should be carried out in cooperation with a multidisciplinary team of experts in the fields of ecology, hydrology, chemistry, public health and other relevant fields. To prevent the development of threats with an increased risk of aquatic ecosystems contamination caused by climate change, it is important to monitor the quality of aquatic ecosystems, to enhance pollution precautions, and to implement climate change adaptation measures, such as the improvement of infrastructure of rainwater management and water source protection. Moreover, it is essential to regulate and reduce the emissions of pollutants so that their influence on aquatic ecosystems is minimized.

From discussions taking place among Czech water management specialists, experts and the media dealing with this subject matter, it is apparent that all involved parties are concerned about the decrease of rain precipitation in certain regions of the Czech Republic, and especially the decrease of snow precipitation and their amount within the Czech Republic. If the irregularity and intensity of rainfall can be relatively easily substituted by the construction of hydraulic structures which retain rainwater, then snowfall has the dominant influence on the yield of groundwater designated and used particularly for drinking purposes, which currently serves as the only source of drinking water for citizens and for the local infrastructure of the region in question.

The minimization of threats of aquatic ecosystems contamination in the Czech Republic requires a complex approach, which includes the regulation of industrial emissions, the improvement of wastewater treatment, the support of sustainable agricultural practises, the protection of natural biotopes and water sources, and the support for the education of the public on the importance of aquatic ecosystems protection.Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

Author Contributions

"Conceptualization, Š.K., Š.K. and M.A.; Methodology, Š.K. and ŠK.; Investigation, Š.K., Š.K. and M.A.; Resources, Š. Kavan.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Š.K., Š.K. and M.A..; Writing – Review & Editing, Š. Kavan.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative data collected is directly available in the core of this article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bozek, F. , Bumbova, A., Bakos, E., Bozek, A., Dvorak, J. Semi-quantitative risk assessment of groundwater

resources for emergency water supply. Journal of Risk Research. 2014, 18(4), 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivančík, R. , Nečas, P. Towards enhanced security: Defense expenditures in the member states of the european union. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues. Vol. 6, Issue 3, pp. 373 – 382. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bross, L. , Krause, S. Preventing Secondary Disasters through Providing Emergency Water Supply. In: World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2017. 2017, Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, pp. 431-439. [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M; Szopinska, K.; Sieminska, E. Value of land properties in the context of planning conditions risk on the example of the suburban zone of a Polish city. LAND USE POLICY, 2021, Vol. 109. [CrossRef]

- Hajkowicz, S. , Higgins, A. A comparison of multiple criteria analysis techniques for water resource management. European Journal of Operational Research. 2008, 184(1), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, H. , Bazargan, J., Mousavi, S., M. A Compromise Ratio Method with an Application to Water Resources Management: An Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set. Water Resources Management. 2013, 27(7), 2029-2051. [CrossRef]

- Kováčová, L. , Vacková M. Achieving of environmental safety through education of modern oriented society. In: 14th SGEM GeoConference on Ecology, Economics, Education And Legislation. SGEM 2014 Conference Proceedings. 2014, Vol. 2, 3-8 pp., ISBN 978-619-7105-18-6 / ISSN 1314-2704,. [CrossRef]

- Quevauviller, P. Water Sustainability and Climate Change in the EU and Global Context – Policy and Research Responses. Sustainable Water. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84973-019-8. [CrossRef]

- Quevauviller, P. Adapting to climate change: reducing water-related risks in Europe – EU policy and re-search considerations. Environmental Science & Policy. 2011, 14 (7), 722-729. [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, B. Global climate change and its impacts on water resources planning and management: as-sessment and challenges. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment. 2011, 25(4), 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, M. , Harper, D. M., Blaskovicova, L. et al. Climate Change and European Water Bodies, a Review of Existing Gaps and Future Research Needs: Findings of the ClimateWater Project. Environmental Management. 2015, 56(2), 271-285. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contri-bution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T. F., D. Qin, G. -K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P. M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 s. 2013. Available at: http://www.climatechange2013. org/images/report/WG1AR5_ALL_FINAL.pdf.

- Richey, A. , Thomas, S., B. F., Min-Hui Lo, Reager, J., S. Famiglietti, Voss, K., Swenson, S., Rodell, M. Quantifying renewable groundwater stress with GRACE. Water Resources Research. 2015, 51(7), 5217-5238. [CrossRef]

- Information and External Relations Division of UNFPA. ISSN 0043-1397. 2015.

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. New York: United Na-tions. ISBN 978-92-1-151517-6. 2014. Available from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2014-Hig hlights.pdf.

- Eigenbrod, F. , Bell, V. A., Davies, H. N., Heinemeyer, A., Armsworth, P. R., Gaston, K. J. The impact of projected increases in urbanization on ecosystem services. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sci-ences. 2011, 278 (1722), 3201-3208. [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, M. , Szidarovszky, F. Revising the OWA operator for multi criteria decision making problems under uncertainty. European Journal of Operational Research. 2009, 198(1), 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützhøft, H., CH. H., Donner, E., Wickman, T., Eriksson, E, Banovec, P., Mikkelsen, P., S., Ledin, A. A source classification framework supporting pollutant source mapping, pollutant release prediction, transport and load forecasting, and source control planning for urban environments. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2012, 19 (4), 1119-1130. [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B. S. et al. Spatial and temporal changes in cumulative human impacts on the world’s ocean. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6:7615. [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace International. Hidden consequences: The costs of industrial water pollution on people, planet and profit. Amsterdam: Greenpeace International. 2011. Available from: http://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/Global/eu-unit/reportsbriefings/2011%20pubs/5/Hidden%20Consequences.pdf.

- Pistocchi, A, Marinov, D. , Pontes, S., Gawlik, B., M. Continental scale inverse modeling of common organic water contaminants in European rivers. Environmental Pollution. 2012, 162, 159–167. [CrossRef]

- Lofrano, G. , Libralato, G., Acanfora, F., G., Pucci, L., Carotenuto, M. Which lesson can be learnt from a historical contamination analysis of the most polluted river in Europe? Science of The Total Environment. 2015, 524-525, 246-259. [CrossRef]

- Intrieri, E. , Dotta, G., Fontanelli, K., Bianchini, Ch., Bardi, F., Campatelli, F. Casagli. N. Operational

framework for flood risk communication. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2020, Florencie,

Itali, 46, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hálová, P. , Alina, J. Analysis of investment in infrastructure and other selected determinants influence to unemployment in CR regions. 8th International Days of Tatistics and Economics, pp. 445-455. 2014.

- Addo-Bankas, O.; Zhao, Y.; Gomes, A.; Stefanakis, A. Challenges of Urban Artificial Landscape Water Bodies: Treatment Techniques and Restoration Strategies towards Ecosystem Services Enhancement. Processes 2022, 10, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, H.V.; Radinja, M.; Rizzo, A.; Kearney, K.; Andersen, T.R.; Krzeminski, P.; Buttiglieri, G.; Ayral-Cinar, D.; Comas, J.; Gajewska, M.; et al. Management of Urban Waters with Nature-Based Solutions in Circular Cities—Exemplified through Seven Urban Circularity Challenges. Water, 2021, 13, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazansky, R. The Definition Frame of the Conflict of the Crisis Management in the International Relations. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Volume 257, pp. 105 – 130. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ivančík, R. , Andrassy, V. Insights into the Development of the Security Concept. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues. Vol.10. Issue4, pp. 26-39. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, J.; Ferreira, F.; Brito, R.S.; Matos, J.S. Development of Resilience Framework and Respective Tool for Urban Stormwater Services. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimaee, R.; Kiani, A.; Jarahizadeh, S.; Haji Seyed Asadollah, S.B.; Melgarejo, P.; Jodar-Abellan, A. Long-Term Water Quality Monitoring: Using Satellite Images for Temporal and Spatial Monitoring of Thermal Pollution in Water Resources. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odume, O.N.; de Wet, C. A Systemic-Relational Ethical Framework for Aquatic Ecosystem Health Research and Management in Social–Ecological Systems. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Zhan, X. Delineating Urban Growth Boundaries with Ecosystem Service Evaluation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subriadi, A., P. and Najwa, N., F.. The consistency analysis of failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) in information technology risk assessment. HELIYON. 2020, Vol. 6. No. 1. [CrossRef]

- Loukas, A., N. Mylopoulos a L. Vasiliades. A Modeling System for the Evaluation of Water Resources Management Strategies in Thessaly, Greece. Water Resources Management. 2007, 21(10), 1673-1702 [cit. 2018-02-10]. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T., H. , Liu, W., Ch. A. General Overview of the Risk-Reduction Strategies for Floods and Droughts. Sustainability. Hsinchu, Thajvan, 2020, 12(7). [CrossRef]

- 75/440/EHS, Směrnice Rady ze dne 16. června 1975 o požadované jakosti povrchových vod určených v členských státech k odběru pitné vody.

- 2000/60/ES Směrnice Evropského parlamentu a Rady ze dne 23. října 2000, kterou se stanoví rámec pro činnost Společenství v oblasti vodní politiky.

- 79/869/EHS, Směrnice Rady ze dne 9. října 1979 o metodách stanovení a četnosti vzorkování a rozborů povrchových vod určených v členských státech k odběru pitné vody.

- United Nations World Water Assessment Programme. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015: Water for a Sustainable World. Paris, UNESCO. 2015, ISBN 978-92-3-100099-7. Available from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002318/231823E.pdf.

- Brumar, J, Brumarova, L, Pokorny, J. Airport integrated operational center. In: 2018 XIII International Scientific Conference - New Trends in Aviation Development (NTAD). 2018, Kosice: IEEE. ISBN 978-1-5386-7918-0. [CrossRef]

- Dušek, J. International Cooperation of Regional Authorities of the Czech Republic: History, Presence and Future. In Conference Proceedings „18th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences“. 2015, Brno: Masaryk University - Faculty of Economics and Administration, pp. 300-305. ISBN 978-80-210-7861-1. WOS:000358536300040. [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, A, Azadi, H., Tomeckova, K., Sklenicka, P. Contrasting effects of land tenure on degradation of Cambisols and Luvisols: The case of Central Bohemia Region in the Czech Republic. LAND USE POLICY, 2020. Vol. 99. [CrossRef]

- Rehak, D. , Senovsky, P. , Hromada, M., Lovecek, T. Complex approach to assessing resilience of critical infrastructure elements. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection, 2019, 25, pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehovská, L. , Skalická, Z. F., Simák-Líbalová, K. Líbal, L. Safety research of population according to population differentiation in Czech Republic. International Journal of Education and Information Technologies. Vol. 9, pp. 12-20. 2015. ISSN 2074-1316.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).