1. Introduction

Malaria is a tropical and subtropical mosquito-borne parasitic disease that continues to cause unacceptably high levels of illness and deaths in sub-Saharan Africa despite progress made in disease control [

1]. The disease is transmitted by female

Anopheles mosquitoes that breed in freshwater bodies in warm and humid environments [

2]. Severe and fatal malaria is predominantly caused by

Plasmodium falciparum, which accounts for more than 90% of the world’s malaria mortality [

3]. In 2022, 249 million malaria cases were recorded in 85 malaria-endemic countries, providing a case incidence of 58 cases per 1,000 population at risk [

4]. The available malaria preventive tools include vector control measures, chemoprophylaxis, and preventive chemotherapies [

5].

Vaccination has been recently added to the malaria prevention package, following prequalification by the World Health Organization (WHO) of two vaccines: RTS/AS01, approved in 2022 [

6], and R21, approved in 2023 [

7]. These two vaccines are recommended as additional tools for preventing

Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children living in moderate to high malaria transmission areas. RTS,S/AS01 was piloted as part of the Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme (MVIP) in three African countries (Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi). Nearly 2 million children have received the vaccine through this initiative since 2019 [

8]. These pilot programmes demonstrated their safety and effectiveness, and their use led to a substantial reduction in severe malaria cases and a significant decrease in child deaths, even in areas where other preventive measures were present [

8]. R21 has recently reached the primary one-year endpoint in a pivotal large-scale phase III clinical trial, including 4,800 children across Burkina Faso, Kenya, Mali, and Tanzania [

9].

Cameroon is one of the 11 countries with a high malaria burden [

4]. The disease is widespread and endemic and is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children under five [

10,

11]. In 2022, Cameroon reported 5.7 million suspected malaria cases, including 3.3 million confirmed cases and 2,481 related deaths [

4]. The malaria preventive interventions in Cameroon include vector control measures such as long-lasting insecticidal nets, intermittent preventive treatment administered to pregnant women since 2015, seasonal malaria chemoprevention implemented since 2017 in the Far North and North Regions, and perennial malaria chemoprevention rolled out in 2022. In addition, malaria cases are managed with medications as per current WHO guidelines.

Following the prequalification of RTS,S/AS01 and its successful pilot rollout in three African countries, the Cameroon government decided to introduce the malaria vaccine into its routine immunization programme and as part of the malaria control package. The country applied for RTS,S/AS01 allocations through the Gavi Vaccine Introduction grant and received the first shipment of 331,200 doses (out of 701,211 doses required in 2024) on 21 November 2023 [

10]. The Cameroon Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) developed a roadmap towards the effective rollout of the malaria vaccine, including indicators for periodically monitoring national and district readiness. As a result of subnational high-disease-burden and high-vaccination-impact analysis, 42 health districts among the most at risk for malaria were selected for the introduction of the vaccine across the country’s ten regions. On 22 January 2024, Cameroon kicked off the malaria vaccine rollout.

This paper summarizes the introduction process, data completeness from health facilities, and preliminary vaccine uptake results one month following the vaccine rollout.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data on key vaccine events of the malaria vaccine introduction (MVI) roadmap and vaccine uptake during the first 30 days of the rollout in Cameroon.

2.1. Study settings

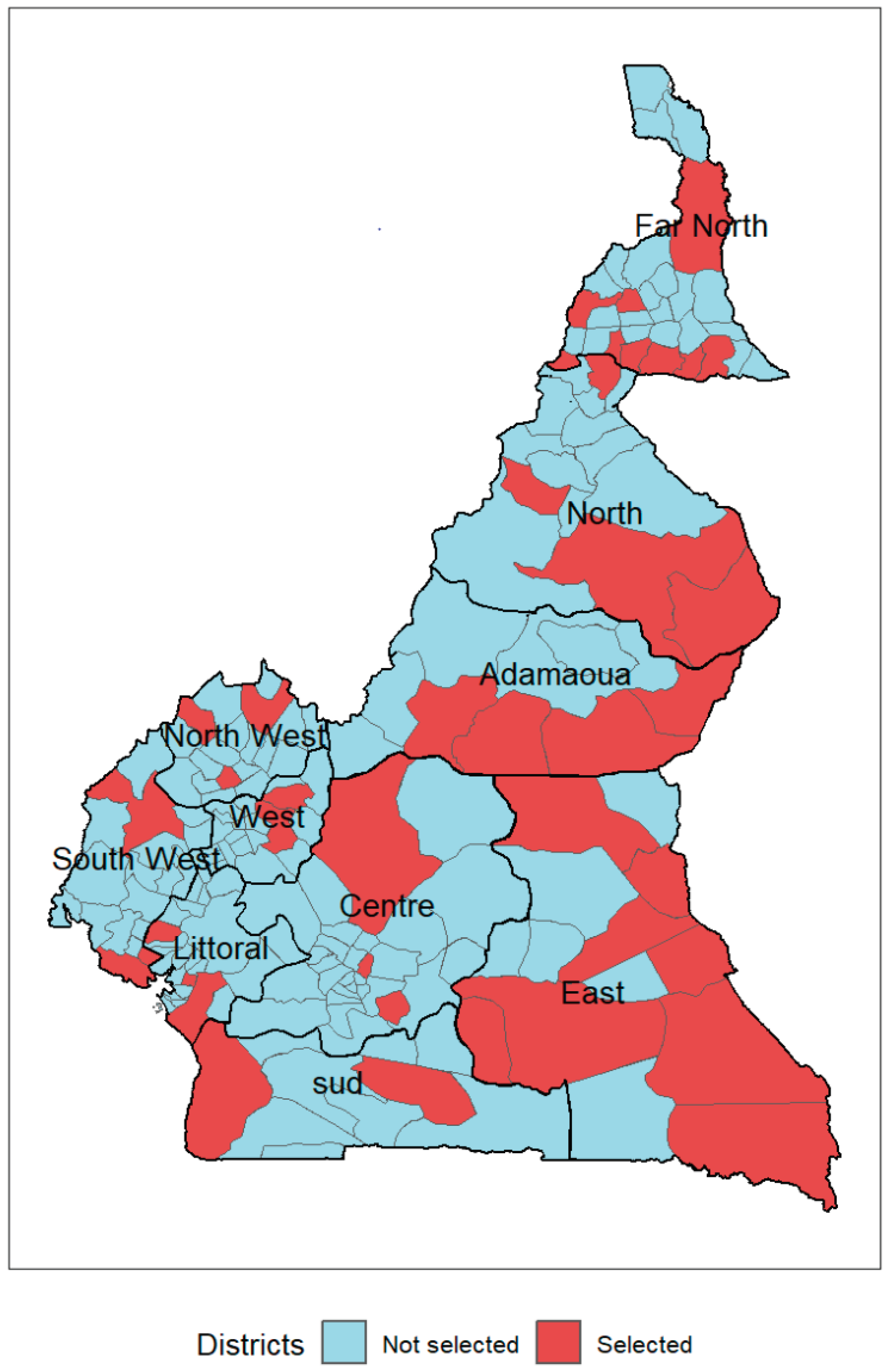

The health system in Cameroon is divided into ten regions and 200 health districts. Forty-two districts among the most at risk for malaria were selected for the MVI following sub-national tailoring analysis [

12].

Table 1 presents the number and percentage of districts chosen for the MVI by region.

Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of districts selected for the MVI by region.

2.2. Eligibility, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

As per the national plan for MVI, RTS,S/AS01, the schedule comprises four doses administered to children at 6, 7, 9, and 24 months of age.

Children born before July 2023, i.e., aged 7 months or above in January 2024, were not eligible for malaria vaccines.

Data from health facilities outside the 42 selected districts and any record of the second or third malaria vaccine dose were considered errors and excluded accordingly.

All public and private health facilities in the 42 districts were allowed to deliver malaria vaccines.

2.3. Data sources

Available gray literature related to the MVI in Cameroon, including minutes of the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) and the MVI Technical Working Group (TWG) meetings, the national plan for MVI, and official statements related to MVI, were reviewed to build a dataset on events of the MVI roadmap in Cameroon.

Data from the national database on routine immunization in the 42 districts selected for the MVI was also analyzed. In these districts, data on routine immunization were collected by vaccination session using a digital form deployed in IASO, an open-source geo-structured data collection platform developed by Bluesquare [

13], a global health information systems and data management company supporting the Ministry of Health in Cameroon. Data on the number of children vaccinated by health facility and antigen, including malaria vaccine doses, were disaggregated by gender and by vaccination strategy (fixed, outreach, and mobile).

2.4. Data analysis

Data on key events were analyzed to draw a timeline of key events from the NITAG recommendation to the vaccine rollout kick-off.

Using the dataset on vaccine uptake from the IASO platform, duplicate records based on the region name, district name, health area name, health facility name, vaccination strategy, and date of reporting were systematically removed using a script that keeps only the first record.

The following parameters were computed:

Reporting completeness: number of reports received from health facilities (by vaccination session) reported during a specified period (month in this study) divided by the total number of reports expected in the 42 selected districts and multiplied by 100. The number of expected reports was calculated by multiplying the number of health facilities by the average number of vaccination sessions per health facility and month.

Immunization coverage: number of eligible children who have received the first dose of malaria vaccine divided by the total number of eligible children at the assessment date, multiplied by 100.

Number of unvaccinated children: total eligible children at the assessment date minus number of children who received the first malaria vaccine dose.

Percentage of girls vaccinated: number of girls vaccinated divided by the total number of children vaccinated, multiplied by 100.

Percentage of boys vaccinated: number of boys vaccinated divided by the total number of children vaccinated, multiplied by 100.

Percentage of children vaccinated in fixed sessions: number of children vaccinated during fixed sessions divided the total number of children vaccinated, multiplied by 100.

Percentage of children vaccinated in outreach sessions: number of children vaccinated during outreach sessions divided by the total number of children vaccinated, multiplied by 100.

Percentage of children vaccinated in mobile sessions: number of children vaccinated during mobile sessions divided by the total number of children vaccinated, multiplied by 100.

All data analyses and visualizations were performed using R software, version 4.3.1 [

14].

This study used data abstracted from the Ministry of Health database and did not require ethical clearance.

3. Results

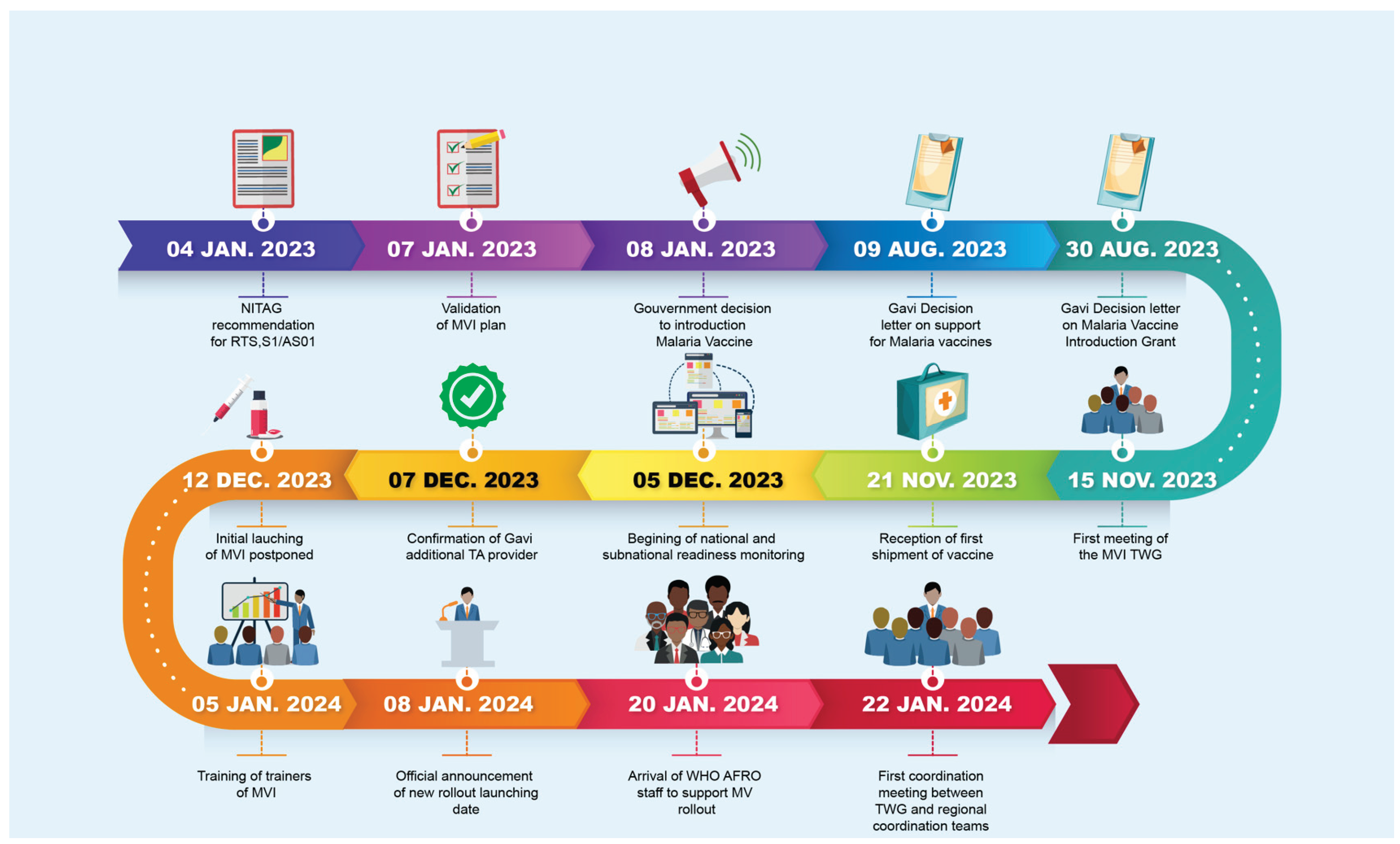

3.1. Timeline of key events related to the MVI

Figure 2 shows the timeline of key events from the recommendation of RTS,S/AS01 by the NITAG to the effective start of vaccine rollout. The MVI was kicked off 383 days (12.8 months) after the recommendation of RTS,S/AS01by the NITAG and 62 days (2 months) after the reception of the first shipment of malaria vaccines.

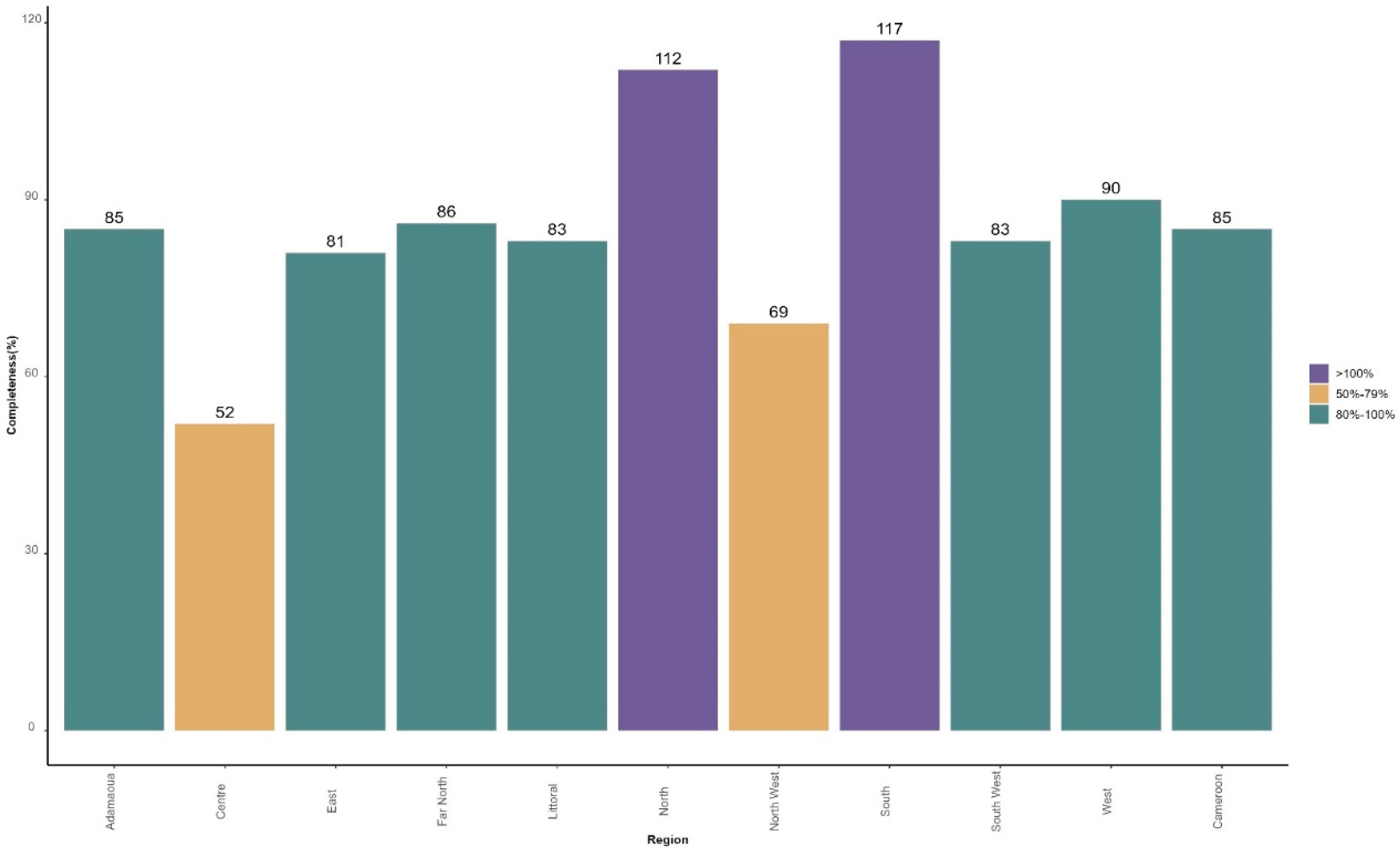

3.2. Completeness of data reporting from health facilities

Based on the number of vaccination sessions planned in each of the 802 health facilities selected for the MVI, 2,240 reports were expected by month, including 1,893 reports received from 22 January to 21 February 2024, from 766 health facilities, providing 85% of overall completeness.

Figure 3 presents the distribution of the completeness in terms of number of reports received over expected by region.

Two regions recorded less than 80% of completeness: Centre (52%) and North West (69%). Two other regions received more reports than expected: North (112%) and South (117%). This is because some health facilities carried out additional vaccination sessions, especially during the first week of MVI.

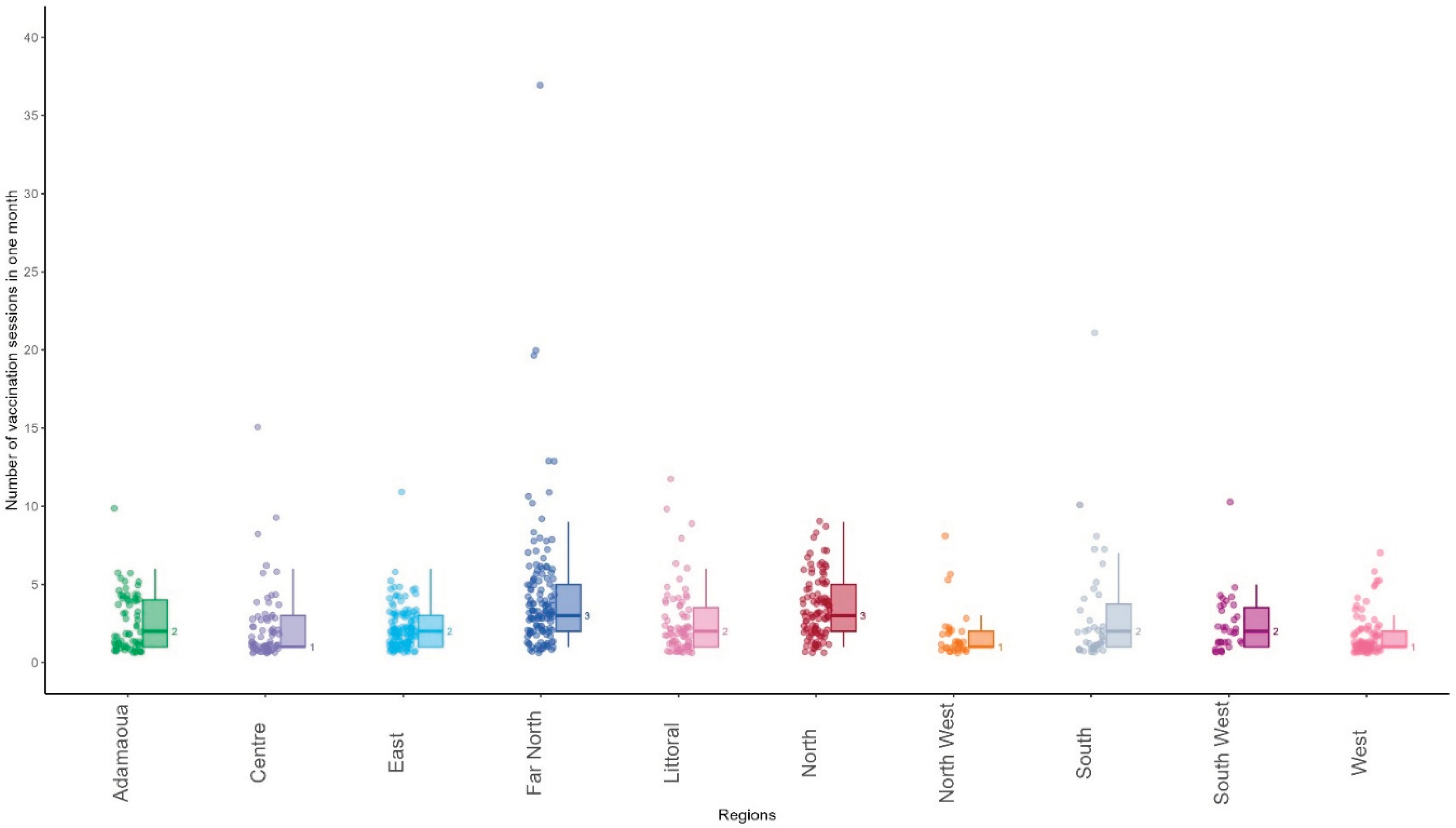

3.3. Vaccination sessions carried out by health facilities

A total of 3,026 vaccination sessions were carried out from 22 January 2024 to 21 February 2024 by 766 health facilities, providing an average of 3.9 sessions by health facility. The median number of vaccination sessions carried out by health facilities was 1 [range: 1;7] in West, 1 [range:1;8] in North West, 1 [ range: 1;15] in Centre, 2 [range: 1;10] in Adamaoua, 2 [range: 1;11] in East, 2 [range:1;12] in Littoral, 2 [range: 1;21] in South, 3 [range:1;9] in North and 3 [range 1;37] in Far North.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the number of vaccination sessions carried out during the first month of MVI by 766 health facilities that submitted reports on malaria vaccine uptake.

Overall, of the 766 health facilities that reported malaria vaccine uptake, 555 conducted fewer than four vaccination sessions during the first month of introduction (72%). A total of 211 health facilities carried out at least one vaccine session per week (38%).

Of the 3,026 vaccination sessions carried out, 2,064 were fixed (68.2%), 915 were outreach (30.2%), 31 were mobile (1.0%), and 16 were not specified (0.6%). The median percentage of outreach sessions was 13.6%, ranging from 1.9% in South West to 46.7% in the Far North and 48.7% in the North.

3.4. Children vaccinated with the first dose of RTS,S/AS01

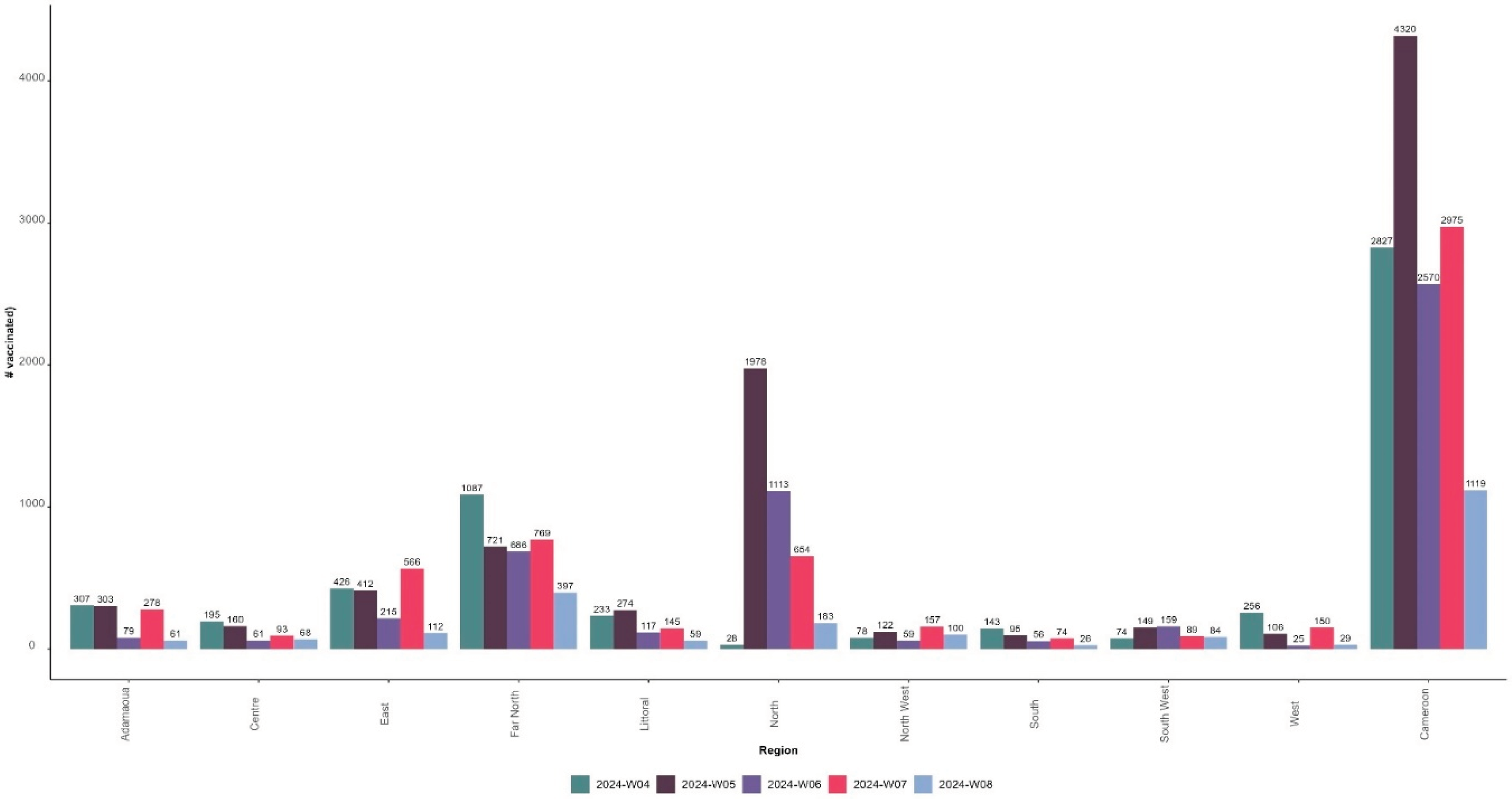

As of 21 February 2024, 13,811 children have received the first dose of the malaria vaccine, including 7,124 girls (51.6%) and 6,687 boys (48.4%). The number of children vaccinated during the ISO week 4, corresponding to the first week of the MVI and the third week of the month of January, was 2,827 in the 42 districts. This number increased by 53% in ISO week 5 (fourth week of January) compared to the previous week (n=4320) before decreasing by 41% in ISO week 6 (first week of February) (n=2570) and increasing by 16% in ISO week 7 (second week of February 2024) (n=2,975) but still below the level of ISO week 5.

Figure 5 presents the distribution of the number of children vaccinated with the first dose of malaria vaccine by ISO week and region and at the national level from 22 January to 21 February 2024.

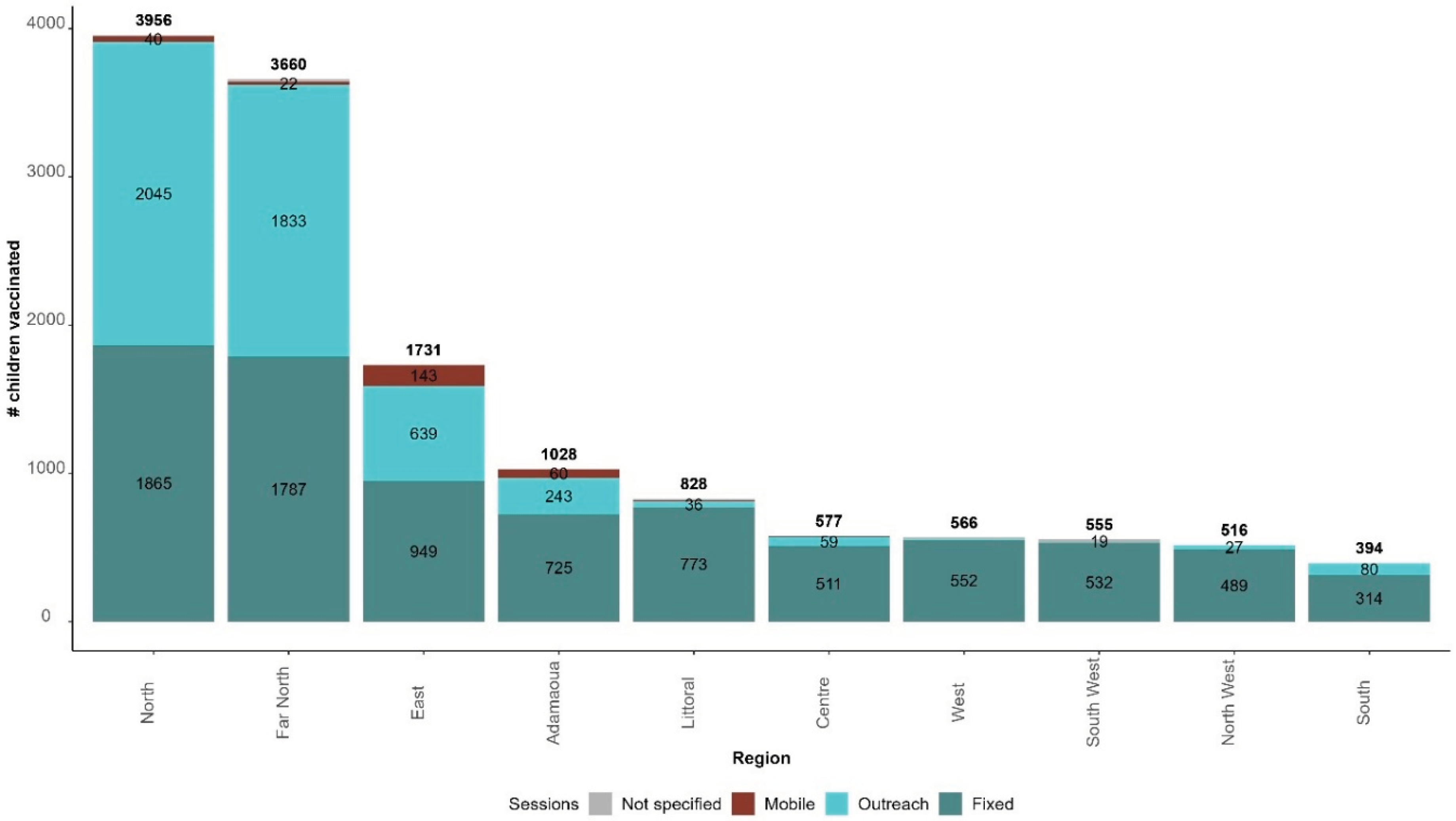

Of the 13,811 children vaccinated with RTS,S/AS01, 8,497 were vaccinated through fixed sessions (61.5%), 4,976 through outreach sessions (36.0%), 282 through mobile sessions (2.0%); and the strategy was not specified for 56 children (0.5%).

Figure 6 presents the distribution of children vaccinated from 22 January 2024 to 21 February 2024 by strategy and region.

North, Far North, and East regions recorded the highest number of children vaccinated and are the regions with the highest proportion of children vaccinated through outreach sessions: 51.7%, 50.1%, and 36.9%, respectively.

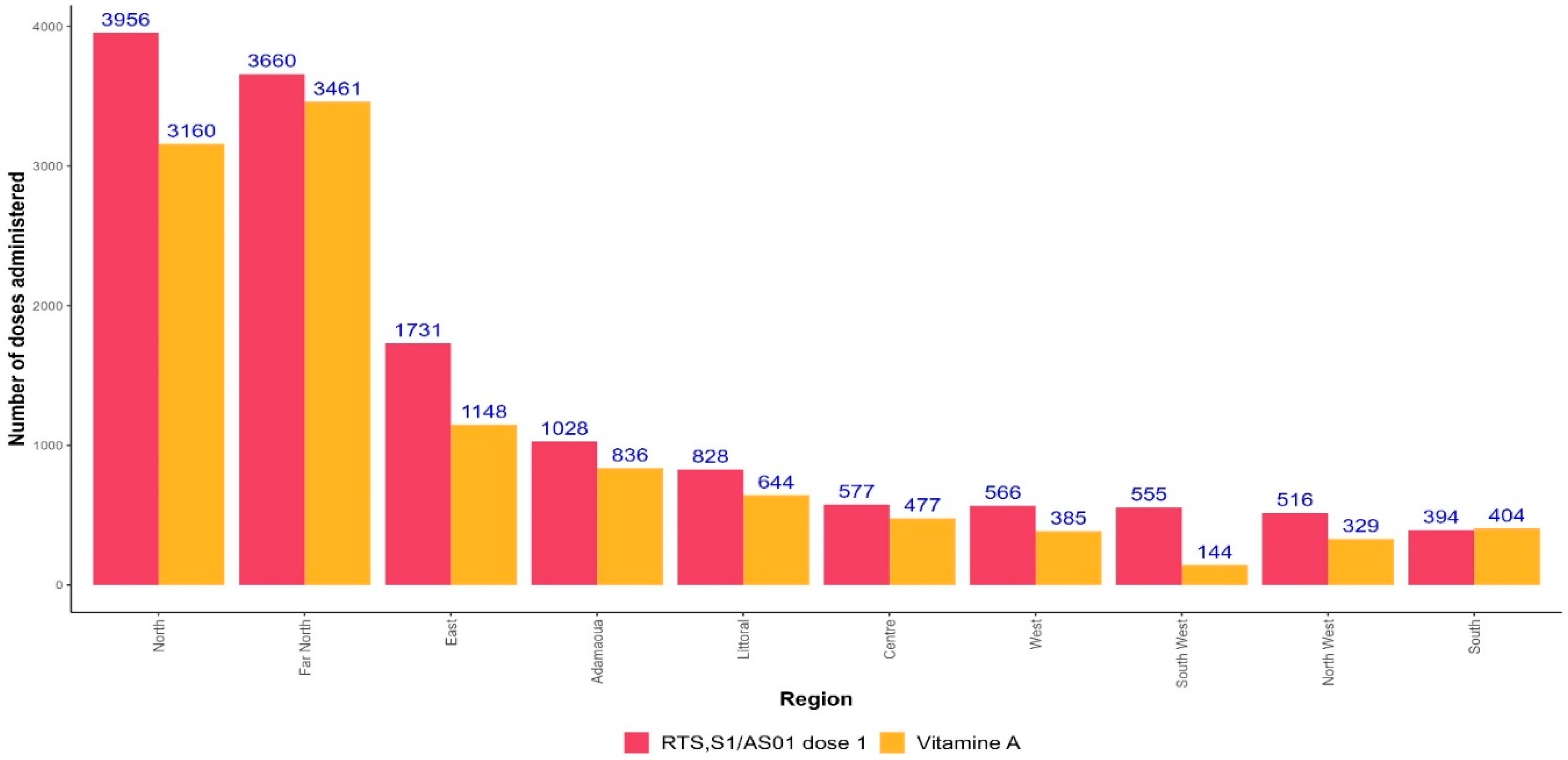

3.5. Co-administration of RTS,S/AS01 and Vitamin A

The first dose of RTS,S/AS01 is administered simultaneously with Vitamin A. Overall, the number of vitamin A doses administered was fewer than those of RTS,S/AS01: 10,988 versus 13,811. In all regions, the number of RTS,S/AS01 doses administered was higher than the number of Vitamin A doses, except in the South region (

Figure 7).

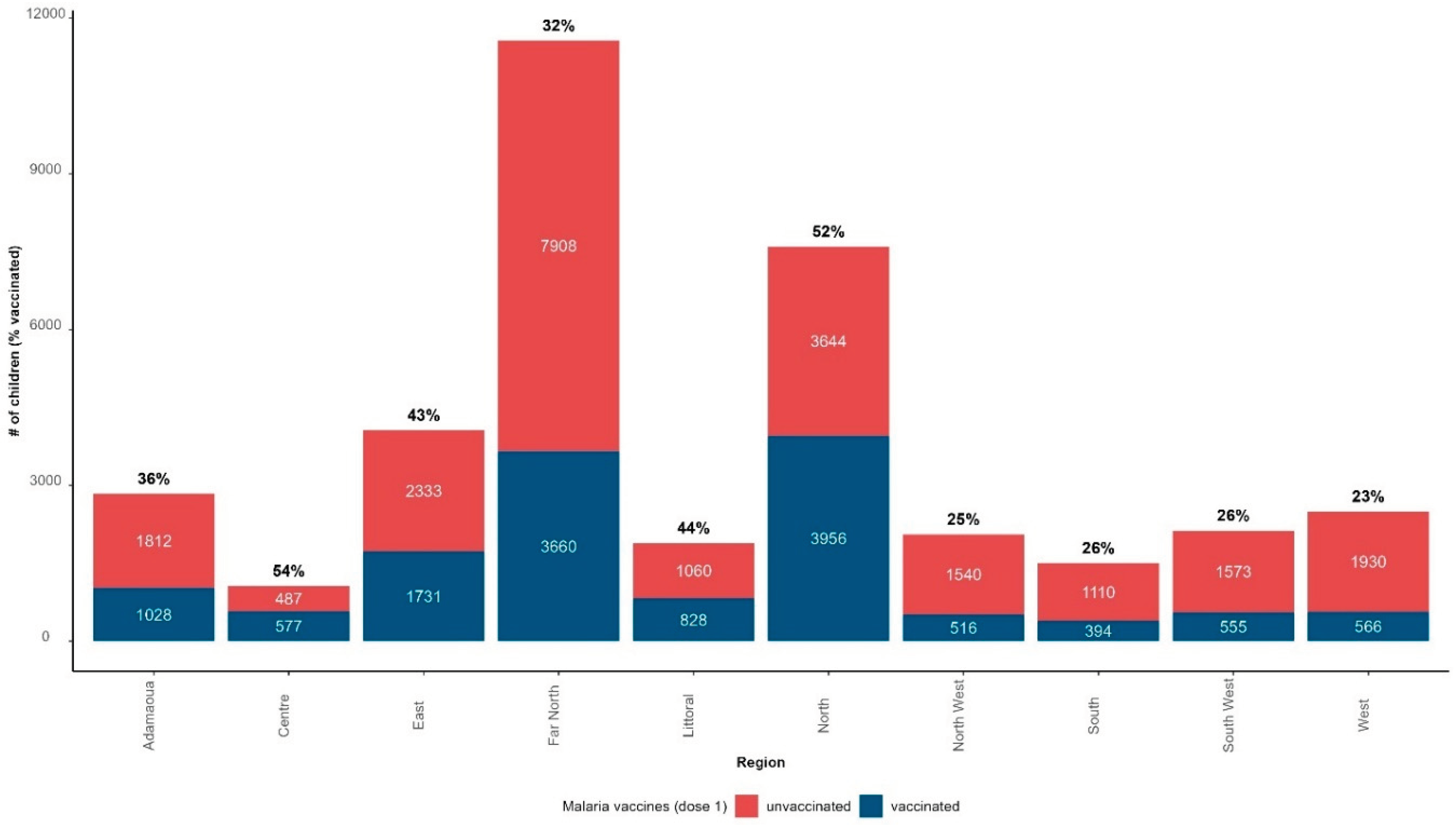

3.6. Vaccination coverage

The monthly immunization coverage with the first dose of malaria vaccine was 37% (13,811 children vaccinated out of 37,208 target population) from 22 January 2024 to 21 February 2024; 23,397 children among the target population did not receive the malaria vaccine (63%).

Figure 8 presents the distribution of children vaccinated and unvaccinated with the first dose of RTS,S/AS01, and the immunization coverage with the first dose of RTS,S/AS01 by region as of 21 February 2024. North (52%), Littoral (44%), and East (43%) were the regions with the highest immunization coverage. Far-North recorded a coverage below the national average despite being the second region with the highest absolute number of children vaccinated with the first dose of RTS,S/AS01.

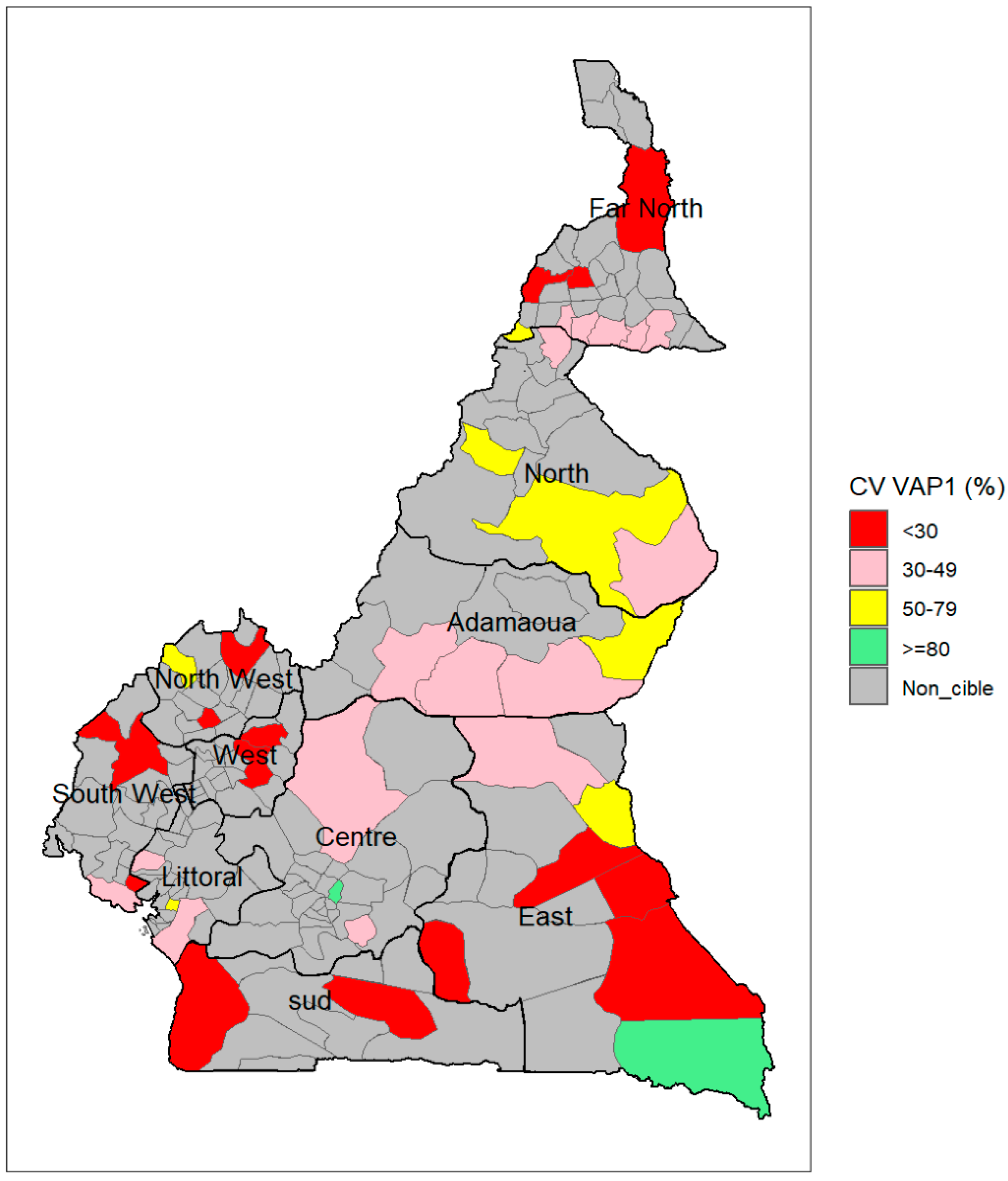

Figure 9 shows the geographical distribution of immunization coverage with the first dose of RTS,S/AS01 by district. Two districts, including one in East (Moloundou) and one in Centre region (Soa), recorded over 80% coverage with the first dose of malaria vaccine (5% of the 42 selected districts), while 12 districts recorded less than 30% coverage (28%), 21 districts between 30% and 49% coverage (50%) and seven districts between 50% and 79% (17%). The two districts surpassing 80% coverage were among the five with the lowest target population.

4. Discussion

Cameroon is the first country to introduce the malaria vaccine into its routine immunization programme outside the pilot programme implemented in three countries (Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi). This introduction occurs after the introduction of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines in 2020 and COVID-19 vaccines in 2021. This resulted in high vaccine hesitancy, leading to low coverage [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Exposure to misinformation and low-risk perception were the main drivers of vaccine hesitancy in the case of COVID-19 and the HPV vaccine in Cameroon. Despite a high level of political commitment, the spread of misinformation suggesting that the malaria vaccine was dangerous and ineffective following receipt of the first shipment led to the initial launch of MVI, scheduled for 12 December 2024, being postponed. In a commentary published in September 2023, Titanji et al. [

19] warned that the rollout of the malaria vaccine coincides with the prevailing challenge of vaccine misinformation and hesitancy, amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic and that assumptions about vaccine acceptance might be faulty. The postponement of the launch gave the Cameroon Ministry of Health time to intensify community-based risk communication involving community leaders and health workers rather than using the usual mass media communication. This targeted risk communication and a high malaria risk perception contributed to the relatively successful launching of MVI in Cameroon, as shown by the figures provided in this paper. Kimbi et al. [

20] found that 92% of pregnant women and caregivers of under-fives in Buea health district, Cameroon, had the correct perception of malaria vaccines.

A total of 13,811 children received the first dose of the malaria vaccine during the first month after its rollout in Cameroon. This number may be underestimated as the completeness of expected reports from health facilities was about 85%. In addition to integrating the malaria vaccine into a routine immunization data system based on end-of-month reporting of aggregated data, Cameroon piloted a new system of reporting routine immunization data by vaccination session [

21]. This system uses an electronic form shaped in IASO and developed by Bluesquare [

13]. Such suboptimal completeness in data reporting, especially for a new and additional reporting system, could, in part, stem from the fact that many frontline immunization staff in Cameroon are commonly overburdened with multiple data-related responsibilities that compete with their clinical tasks and affect their data collection practices [

22]. Temeslow Mamo [

23] from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change identified three cross-cutting data-management challenges related to the use of digital platforms for vaccine rollouts, including weak connectivity and infrastructure (lack of data-collection equipment, poor connectivity in remote districts), poor data-management systems (multiple reporting tools, data not integrated into a single system or platform, lack of interoperability across various systems), and shortage of trained workforce. Through its EPI, the Cameroon Ministry of Health must intensify supportive supervision to identify and address issues preventing completeness in malaria vaccine uptake data reporting.

In this paper, regions that carried out the highest proportion of outreach vaccination sessions, such as North and Far-North, recorded the highest absolute number of children vaccinated with the first dose of malaria vaccine. Akoh et al. [

24], from an assessment of immunization service delivery in one of the largest health districts in the West Region of Cameroon, reported a low proportion of health facilities (4.8%) that organized outreach sessions within the 3 months before the study. Geographical accessibility to vaccination services is known as one of the main drivers of vaccination coverage in Cameroon, so outreach vaccination sessions play a pivotal role in reducing immunization inequities. For Streefland et al. [

25], routine provision of vaccinations using outreach strategies in addition to static facilities has become the backbone of sustainable vaccination systems in developing countries. Investing more in outreach sessions as part of routine immunization could improve the performance of MVI in Cameroon.

The coverage of the monthly target population by the first dose of malaria vaccine at the end of the first month of MVI in Cameroon was low (37%). Even though it is too early to compare the Cameroonian experience with the three pilot programmes, the vaccination coverage for the first dose in 2020 (the first year of implementation) was 88%, 71%, and 69% in Malawi, Ghana, and Kenya, respectively [

26]. In Cameroon, the fact that the number of children who received the first dose of the malaria vaccine in the first 30 days was greater than the number of those who received vitamin A in most regions (the two products being administered at the same time in the immunization schedule), means there is little or no refusal of malaria vaccines in health facilities. The low coverage in Cameroon may result either from overestimating the target population or under-reporting through the new system being piloted in the 42 districts selected for MVI. Supportive supervision could help rule out low coverage because a significant portion of eligible children who reported in health facilities for other vaccines have still not received the malaria vaccine. Carrying out supportive supervision to identify challenges early was among the main lessons learned from the three pilot programmes [

27]. Visits to health facilities by experts from the EPI to witness vaccination in action and provide on-site training to health workers contribute to identifying challenges and ways to address them [

27].

Limitations

Data used in this paper was reported by health facilities from the digital platform for reporting immunization data by vaccination session. No data quality audit has been conducted to assess the consistency of data between paper-based registries and the digital tool.

The completeness of reports received out of expected reports was about 85%. This may have led to an under-estimation of the number of children vaccinated by the first dose of the malaria vaccine.

Duplicate records based on the region name, district name, health area name, health facility name, vaccination strategy, and date of reporting were systematically removed using a script that kept only the first record. This could have led to removing the right record and keeping the wrong one.

The findings of this report should, therefore, be interpreted with these limitations.

5. Conclusions

The recent introduction of the malaria vaccine into routine immunization in Cameroon marks a decisive turning point in malaria control. RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccines have now been administered to eligible children in the most affected districts for malaria in Cameroon for one month. The early results have shown positive attitudes towards and acceptance of malaria vaccines, evidenced by the fact that malaria doses administered were greater than the doses of vitamin A in most regions. However, the suboptimal completeness of data reported and the low coverage highlight persistent gaps and challenges in vaccine rollout. There is an urgent need to conduct a post-introduction evaluation to rapidly identify problem areas since the country will soon start providing the second dose of the vaccine. Health facilities’ compliance with guidance on vaccination for eligible children reporting late, the effectiveness of tracking access to malaria vaccine for eligible children reporting to health facilities for other vaccines, and drivers of delayed or no reporting through the set system should be among the focus areas in such an evaluation. An early post-introduction evaluation will also help to draw lessons for other countries in the African region that have planned to introduce the malaria vaccine in 2024 and 2025.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T.N, F.M., and B.I.; methodology, F.M., A.A.N, A.A. and R.N.; formal analysis, F.M., A.N and R.N.; data curation, J.C.K., C.A.K; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.N, F.M. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, B.F., S.F.B., M.K., A.A., K.V., A.A.N; visualization, F.M. and K.V.; supervision, S.T.N, B.I. and P.H.; project administration, F.M and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all health workers and community health workers from the 766 health facilities and 42 health districts for their contribution to the introduction of the malaria vaccine and submission of data to the central level of the Cameroon Ministry of Health, through the Expanded Programme on Immunization; to the consultants deployed by WHO in the 42 districts to oversee the rollout of malaria vaccines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Poespoprodjo, J.R.; Douglas, N.M.; Ansong, D.; Kho, S.; Anstey, N.M. Malaria. Lancet 2023, 402, 2328–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossati, A.; Bargiacchi, O.; Kroumova, V.; Zaramella, M.; Caputo, A.; Garavelli, P.L. Climate, environment and transmission of malaria. Infez Med 2016, 24, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, R.W. Global malaria eradication and the importance of Plasmodium falciparum epidemiology in Africa. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086173 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Malaria. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommends Groundbreaking Malaria Vaccine for Children at Risk. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2021-who-recommends-groundbreaking-malaria-vaccine-for-children-at-risk (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommends R21/Matrix-M Vaccine for Malaria Prevention in Updated Advice on Immunization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-10-2023-who-recommends-r21-matrix-m-vaccine-for-malaria-prevention-in-updated-advice-on-immunization (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- The lancet. Malaria vaccines: a test for global health. Lancet 2024,403,503. [CrossRef]

- Datoo, M.S.; Dicko, A.; Tinto, H.; Ouédraogo, J.B; Hamaluba, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of malaria vaccine candidate R21/Matrix-M in African children: a multicentre, doubleblind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabi, A.; Djimafo, A.N.M; Nguefack, S.; Mah, E.; Dongmo, F.W; Angwafo, F. Severe malaria in Cameroon: Pattern of disease in children at the Yaounde Gynaeco-Obstetric and Pediatric hospital. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1469–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severe Malaria Observatory. Cameroon: Maria Fact. Available online: https://www.severemalaria.org/countries/cameroon (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Severe Malaria Observatory. Cameroon: Malaria Fact. Available online: https://www.severemalaria.org/countries/cameroon (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Bluesquare. IASO: Geo-Enabled Data Collection and Microplanning. Available online: https://www.bluesquarehub.com/iaso/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

-

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020.

- Haddison, E.; Tambasho, A.; Kouamen, G.; Ngwafor, R. Vaccinators’ Perception of HPV Vaccination in the Saa Health District of Cameroon. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 748910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elit, L.; Ngalla, C.; Afugchwi, G.M.; Tum, E.; Fokom-Domgue, J.; Nouvet, E. Study protocol for assessing knowledge, attitudes and belief towards HPV vaccination of parents with children aged 9–14 years in rural communities of North West Cameroon: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinga, J.N.; Njoh, A.A.; Gamua, S.D.; Muki, S.E.; Titanji, V.P.K. Factors Driving COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Cameroon and Their Implications for Africa: A Comparison of Two Cross-Sectional Studies Conducted 19 Months Apart in 2020 and 2022. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwedi Nolna, S.; Mbang Massom, D.; Tchoteke, L.A; Bille Koffi, A.; Marchant, M.; Masumbe Netongo, P. Perceptions around COVID-19 among patients and community members in urban areas in Cameroon: A qualitative perspective. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0001760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titanji, B.K.; Mekone, I.; Scales, D.; Tchokfe-Ndoula, S.; Seungue, J.; Gorman, S. Pre-emptively tackling vaccine misinformation for a successful large-scale rollout of malaria vaccines in Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimbi, H.K.; Nkesa, S.B.; Ndamukong-Nyanga, J.L.; Sembele, I./U.N.; Atashili, J.; Atanga, M.B.S. Knowledge and perceptions towards malaria prevention among vulnerable groups in the Buea Health District, Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboussou, F.; Ndoula, S.T.; Nembot, R.; Baonga, S.F; Njinkeu, A.; Njoh, A.A; Biey, J.; Kaba, M.; Amani, A.; Farham, B.; Habimana, F.; Impouma, B. Setting up a data system for monitoring malaria vaccine introduction readiness and uptake in 42 health districts in Cameroon. BMJ Glob. Health 2024. (submitted). [Google Scholar]

- Saidu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Ngenge, B.M.; Nchinjoh, S.C; Amani, A.; et al. Assessment of immunization data management practices in Cameroon: unveiling potential barriers to immunization data quality. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. The Africa Vaccines Programme: Utilising Data-Management Tools for Vaccine Delivery. Available online: https://www.institute.global/insights/public-services/africa-vaccines-programme-utilising-data-management-tools-vaccine-delivery (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Akoh, W.E.; Ateudjieu, J.; Nouetchognou, J.S.; Yakum, M.N.; Nemnot, F.D.; Sonkeng, S.N.; Fopa, M.; Watcho, P. The expanded program on immunization service delivery in the Dschang health district, west region of Cameroon: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streefland, P.H.; Chowdhurry, A.M.R.; Ramos, P. Quality of Vaccination Services and Social Demand For Vaccination in Africa and Asia. Bull. World Health Organ. 1999, 77, 728. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Safety Updates on Malaria Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/global-advisory-committee-on-vaccine-safety/topics/malaria-vaccines/malaria-vaccine-implementation-programme (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. Learning Lessons from the Pilots: Overcoming Knowledge Gaps Around the Malaria Vaccine Schedule in Support of Saccine Uptake. Available online: https:// https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/learning-lessons-from-the-pilots--overcoming-knowledge-gaps-around-the-malaria-vaccine-schedule-in-support-of-vaccine-uptake (accessed on 3 March 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).