1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic diseases that recognize two main forms: Crohn's disease (CD), which can affect any part of the digestive tract, and ulcerative colitis (UC), which involves only the colon [

1,

2]. The etiopathogenesis of these diseases is not yet known although several factors are involved: predisposing genetic factors, the role of the intestinal microbiota, the function of the intestinal epithelial barrier, and the innate and specific immune response. In such a complex clinical and pathogenetic context, diet plays a key role both in the development of IBD and in triggering clinical symptoms. Patients with IBD have often the perception that food can worsen their disease and the excessive attention to the quality, quantity, and type of food intake can become unhealthy, leading sometimes to caloric-protein malnutrition [

3,

4].

The medical literature has recently focused on diet in IBD, a neglected topic in the past. The IOIBD consensus has formulated dietary recommendations, which advise reducing trans fats and the intake of red/processed meats and myristic acid (palm oil, coconut oil, dairy fats), and the exposure to maltodextrins, carrageenans, carboxymethylcellulose, polysorbate-80, titanium dioxide and other nanoparticles, [

5]. Recent studies demonstrate symptomatic benefit in patients with IBD who are on reduced carbohydrate diets [

6] or based on the Mediterranean model [

7]. In light of all this evidence, the ESPEN (European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) guidelines recommend: a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, enriched in omega-3 fatty acids and low in omega-6; breastfeeding, as breast milk is the optimal food for infants and reduces the risk of IBD; nutritional screening at the time of diagnosis and on a regular basis thereafter; adequate treatment of malnutrition when documented, as it is associated with worse prognosis, increased rate of complications, mortality, and poorer quality of life; iron supplementation in all patients with IBD in the presence of deficiency anemia. The ESPEN also recommends patients with IBD in remission to be counseled by a dietitian to improve nutritional therapy and avoid malnutrition [

8].

As previous studies have shown, IBD patients have an increased risk of following restrictive eating behaviors and sometimes develop eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and ARFID [

9]. Disordered eating and eating disorders in IBD have been the objective of a recent review by our group [

10]. In contrast, there are no studies dedicated to the correlation between IBD and orthorexia nervosa.

The term orthorexia nervosa

derives from the Greek words "ortho," meaning "correct" or "right," and "orexis," meaning "appetite" or "desire to eat" and was first used by Dr. Steven Bratman in 1997 [

11] and describes a condition characterized by an eating behavior that follows a pathological obsession with biologically pure and healthy food; this leads to a search for natural foods, uncontaminated by artificial chemicals, and an exaggerated scrutiny of food origin, processing, and packaging. Among the most avoided foods there are foods containing preservatives, additives, dyes, food flavorings, excess fat, sugar, salt, or genetically modified foods [

12,

13]. These behaviors cause the avoidance of many foods leading to nutritional deficiencies: the diet becomes depleted, moving away from a dietary pattern considered healthy that is based on balance, variety, and balancing of nutrients. Among the most observed alterations are caloric malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies, osteoporosis, and muscle atrophy. The average prevalence rate of orthorexia is 6.9% for the general population and 35-57.8% for high-risk groups. This variability depends on many factors, including diagnostic criteria and cut-offs, cultural, geographic and gender differences [

11,

13]. Those with orthorexia spend a great deal of time thinking about food, planning, purchasing, preparing, and consuming the foods they consider healthy [

14]. Any deviation from self-imposed norms amplifies feelings of shame, guilt, fear, and increased food restriction [

11,

12].

Orthorexia is a new phenomenon and to date is still not formally recognized as an eating disorder and is not included in the official ICD-11 and DSM-V classifications, and neither the American Psychiatric Association nor the World Health Organization officially recognize orthorexia nervosa as a mental disorder. However, some consider it as a subtype of ARFID. To date, there is still no officially accepted definition or standardized criteria for its diagnosis, and although numerous diagnostic criteria have been proposed [

15,

16], none have proven entirely effective. Between the criteria used in previous studies [

15,

16,

17] and the psychological factors typical of orthorexia nervosa [

18] there are the excessive interest in food (quality, ingredients, health effects), restricted eating habits, perfectionism, need for control, feeling of not being understood, isolation, emotional stress (guilt, shame, anxiety), malnutrition, and loss of body mass. To date, there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of orthorexia nervosa although several tools have been proposed. Among the most widely used instruments there is the ORTO-15 test, designed in 2005 by Donini et al [

19,

20].

2. Material and Methods

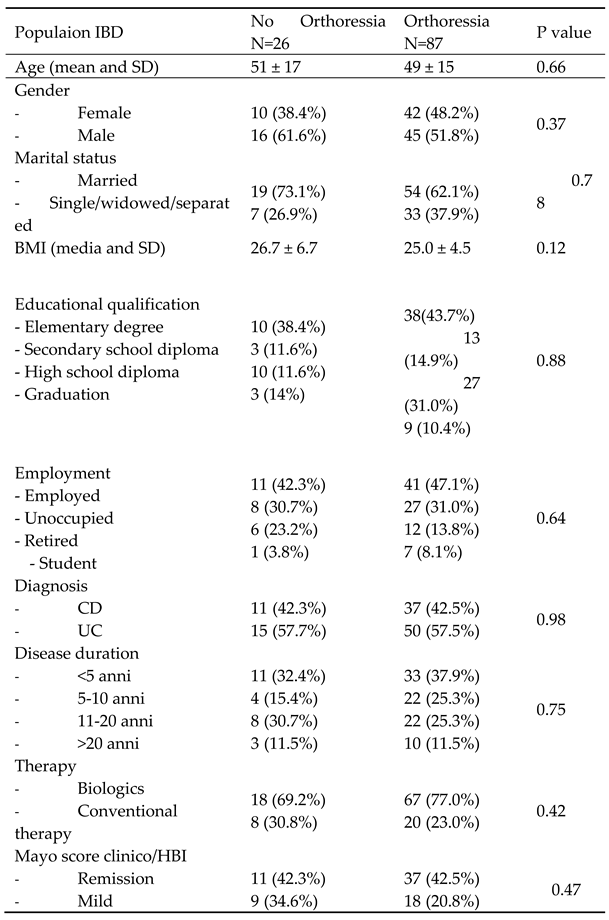

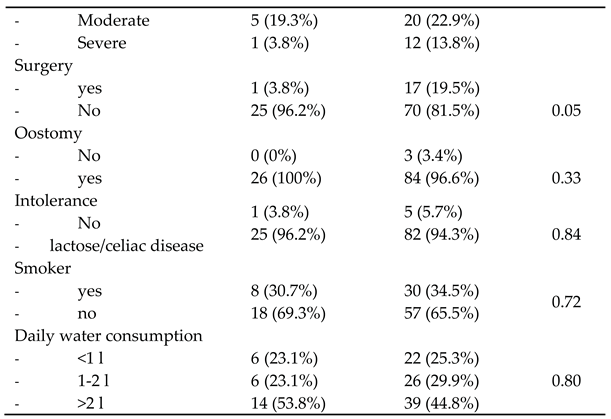

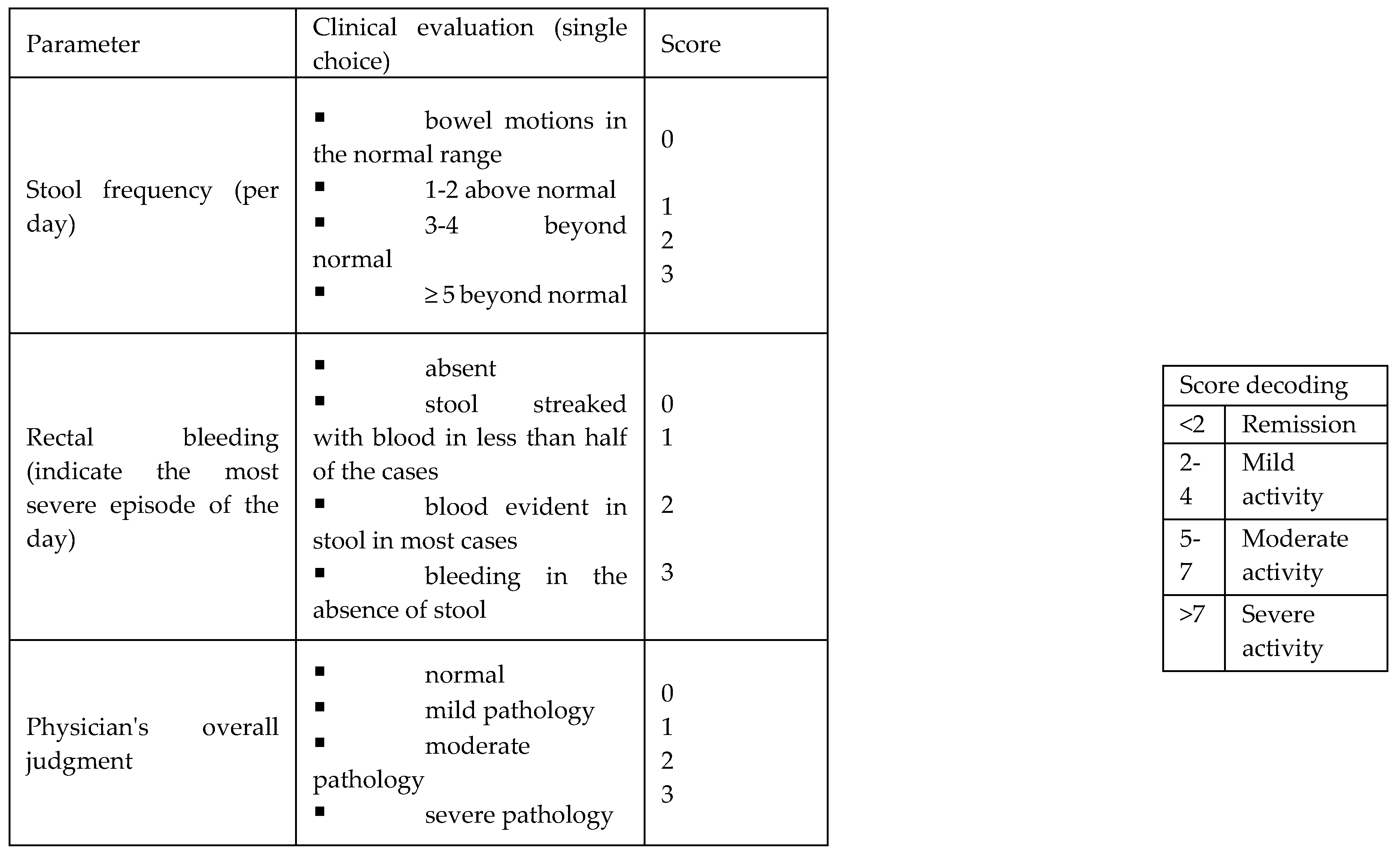

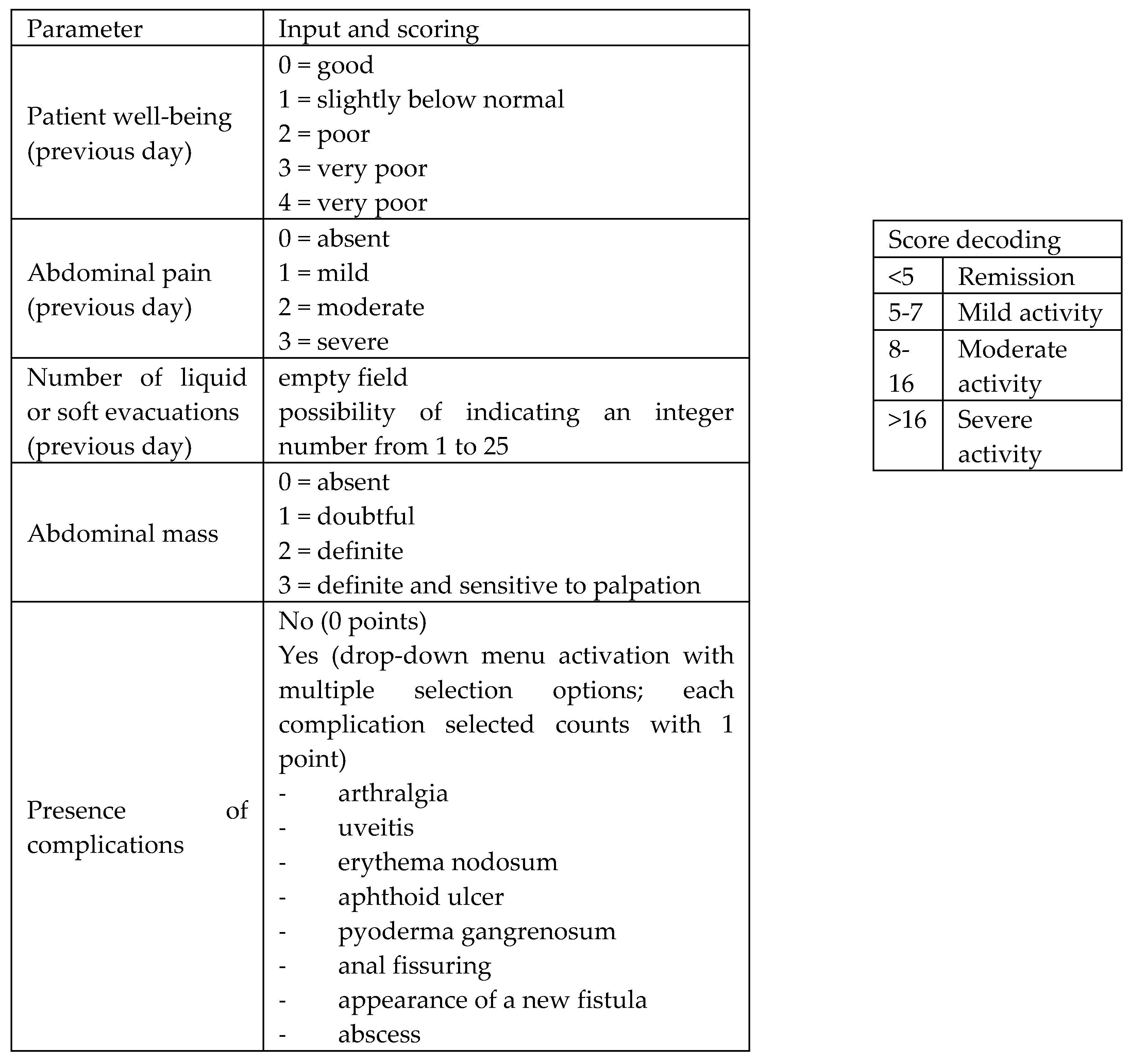

During the period from February to October 2022, 158 consecutive subjects, including 113 patients diagnosed with IBD and 45 controls, were prospectively recruited at the Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit of the University Hospital of Palermo. Specifically, the cohort of patients with IBD consisted of 74 patients on biologic drug treatment (Infliximab, Vedolizumab, Adalimumab, Ustekinumab), 28 patients on conventional therapy, and 12 patients admitted to the gastroenterology department for disease flares. All patients satisfied the following inclusion criteria: age over 18 years, established diagnosis of UC or CD, and consent for voluntary participation in the study. The following data were collected: clinical and demographic data (age, sex, family history of IBD, smoking habits, diagnosed food intolerances), data on marital status, educational qualification and occupational activity, body mass index (BMI), amount of water intake in 24 h, and disease characteristics (type of IBD, activity status, previous surgery, and presence of oostomy) including concomitant therapy. Disease activity status at the time of enrollment was assessed by the partial MAYO score for UC (

Figure 1) and the Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) for CD (

Figure 2). The control group (45 healthy subjects) was composed of 25 individuals including trainees and employees at the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria "Paolo Giaccone" of Palermo and 20 individuals from outside the company. Both IBD patients and controls gave consent to participate in the study. The study involved the administration of the standardized ORTO-15 test questionnaire, validated by Donini et al [

19,

20] (

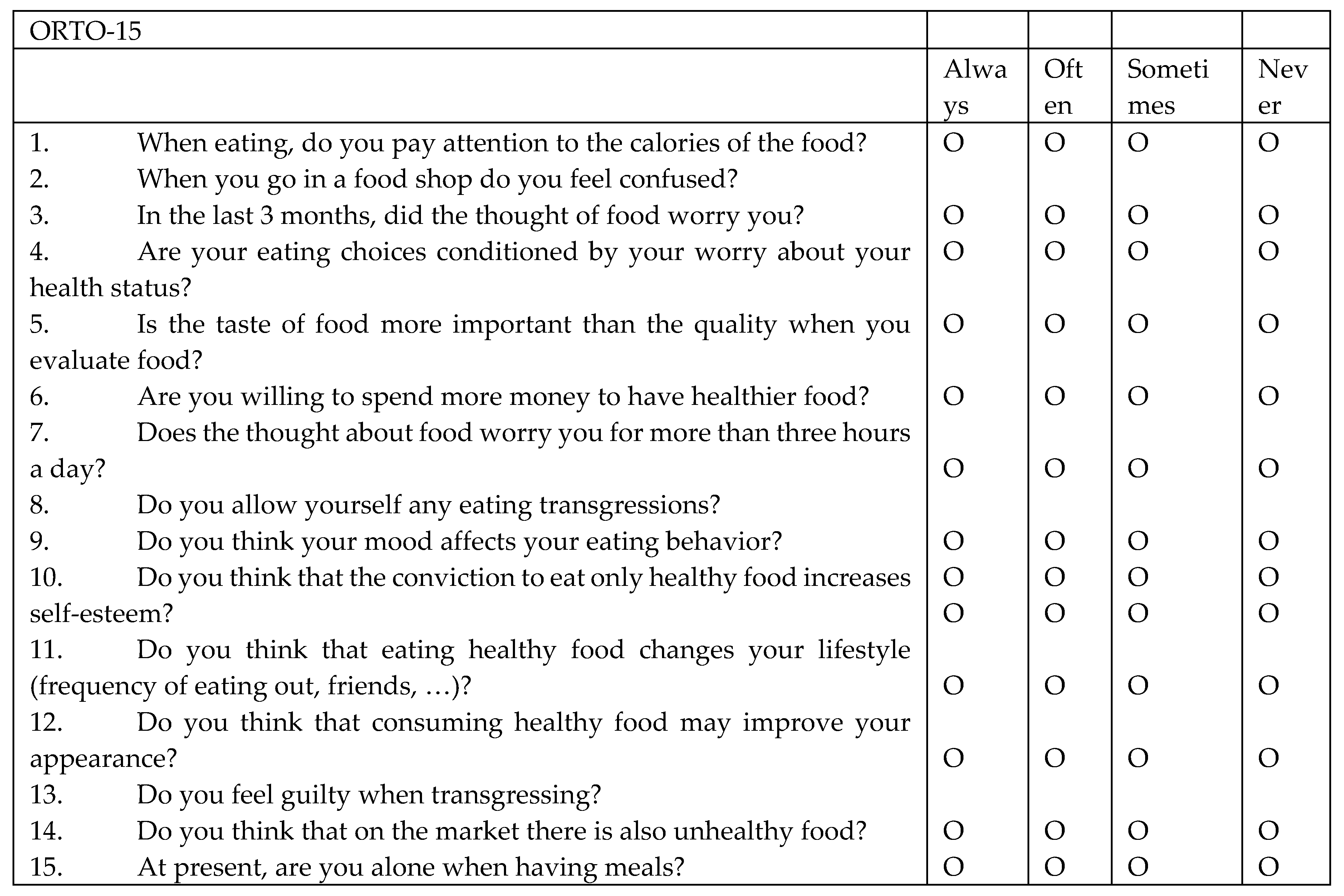

Figure 3). The ORTO-15 scale provides an assessment of behaviors related to food choice, purchase, preparation, and consumption.

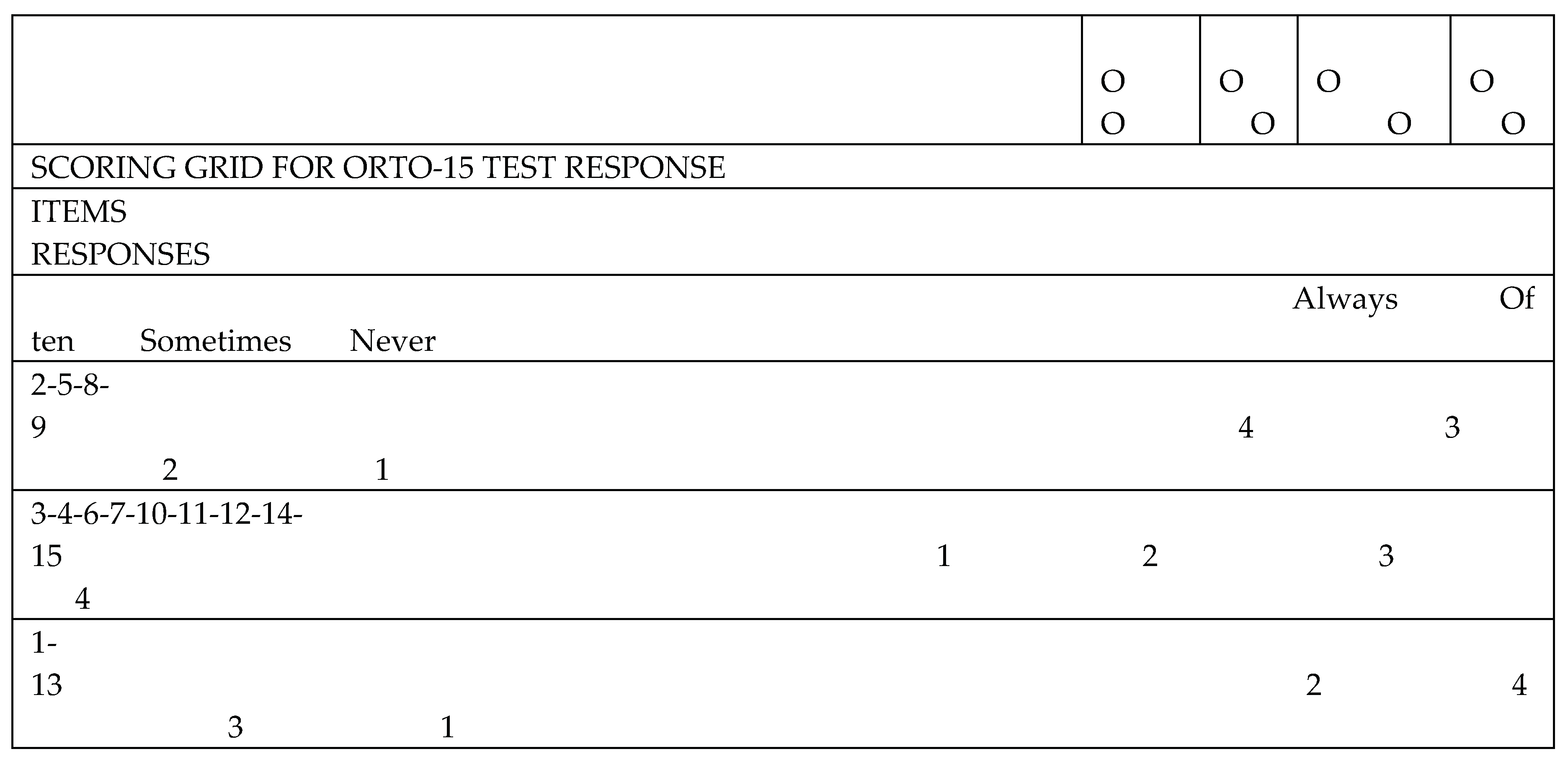

The questionnaire consists of 15 items: 1. When eating, do you pay attention to the calories of the food? 2. When you go in a food shop do you feel confused? 3. In the last 3 months, did the thought of food worry you? 4. Are your eating choices conditioned by your worry about your health status? 5. Is the taste of food more important than the quality when you evaluate food? 6. Are you willing to spend more money to have healthier food? 7. Does the thought about food worry you for more than three hours a day? 8. Do you allow yourself any eating transgressions? 9. Do you think your mood affects your eating behavior? 10. Do you think that the conviction to eat only healthy food increases self-esteem? 11. Do you think that eating healthy food changes your lifestyle (frequency of eating out, friends, …)? 12. Do you think that consuming healthy food may improve your appearance? 13. Do you feel guilty when transgressing? 14. Do you think that on the market there is also unhealthy food? 15. At present, are you alone when having meals?

Questions are separated based on eating behavior: cognitive (items: 1, 5, 6, 11, 12 and 14), clinical (items 3, 7, 8, 9, 15) and emotional (items: 2, 4, 10 and 13). For each question, the patient has 4 response options (always, often, sometimes, never) and to each response is given a score ranging from a minimum of 1 point to a maximum of 4 points. The cut-off validated by Donini for the diagnosis of orthorexia nervosa is a score <40.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, categorical variables as frequency and percentage. The characteristics of patients with IBD compared with controls, and, within the group of patients with IBD, the characteristics of those with orthorexia compared with their counterpart were compared. Student's t-test was used to compare continuous variables, and Chi-square was used to compare categorical variables. A difference with a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

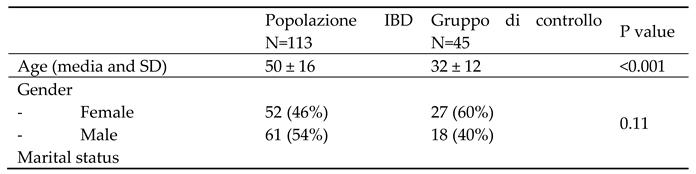

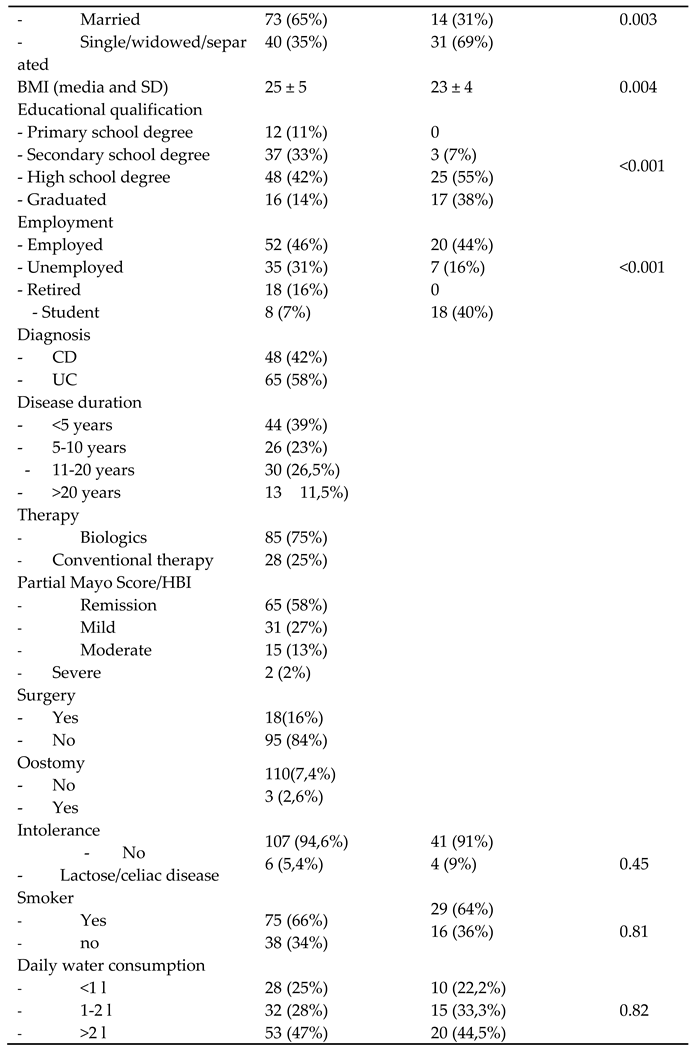

Of the 113 patients who participated in the study, 48 (42%) have UC and 65 (58%) have CD. Mean age was 50 ± 16 years, ranging from 18 to 84 years, there was a slight prevalence of male gender (54%) and a mean BMI of 25± 5 kg/m2. Most patients are Italian (98%) and married (65%), 42% have a high school diploma while only 14% have a college degree. At the time of interview, 46% of patients are employed, 31% are unemployed, 18% are retired, and 8% are students. The diagnosis of IBD was made in the 5 years before the interview in about 40% of patients, between 5 and 20 years before in 49.5%, while only 11.5% of patients have disease duration for more than 20 years. Regarding disease activity assessed by Mayo Partial Score and HBI, 58% are in remission, 27% have mild activity, 13% have moderate activity, and only 2% have severe activity. 16% of the patients have undergone previous resection surgery for IBD and 2.6% are oostomy carriers. Regarding therapy, 75% of patients were treated with biologics while 25% follow conventional therapy. In addition, 5.4% of patients have a diagnosed food intolerance (lactose or gluten), 66% smoke and 47% drink more than 2 liters of water per day.

The control group consists of a sample of 45 subjects, 60% of whom are female and with a mean age of 32 ± 12 years with a range of 18 to 58 years, mean BMI of 23 ± 4 Kg/m2. This population predominantly (69%) have no marital ties, as only a minority (31%) is married. All of them had an educational qualification above primary school (3% had a secondary school degree, 55% a high school degree and 38% a university degree). 44% of these individuals have regular employment, 16% are unemployed, none are retired, and 40% are still students. 9% have a diagnosed food intolerance (lactose/gluten), 64% smoke, and 44.5% drink more than 2 liters of water per day.

Comparison of the IBD patient population with the control group documents how patients with IBD have a significantly higher age and BMI, are more frequently married, have less advanced school degrees, and a lower employment rate (

Table 1).

On the basis of the results of the Donini questionnaire with the cut-off of 40, we found that patients with IBD had a 77% risk of orthorexia, significantly higher than the 47% observed in the control group (p<0.001).

When the analysis was focused on the group of patients with IBD, no statistically significant differences were found between patients with risk of orthorexia and patients without risk of orthorexia in relation to age (p=0.66), gender (p=0.37), marital status (p=0.78), educational qualification (p=0.88), and occupation (p=0.64), although a non-significant trend for lower BMI in patients with risk of orthorexia compared to those without orthorexia could be observed (mean BMI 26.7 VS 25 Kg/m2 , p=0.12). Regarding the characteristics of IBD, the prevalence of orthorexia did not differ in relation to the diagnosis of UC or CD (p=0.98), nor to the duration of the disease (p=0.75), type of biological or conventional therapy (p=0.42), disease activity as measured by Mayo score/HBI (p=0.47) or the presence of oostomy (p=0.33). The only statistically significant difference observed related to the history of previous surgery for IBD: in fact, a prevalence of previous surgery of 19.5% was observed in patients at risk for orthorexia, which was significantly higher than the 3.8% prevalence in patients not at risk for orthorexia (p=0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with risk of orthorexia and without risk of orthorexia.

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with risk of orthorexia and without risk of orthorexia.

4. Discussion

In this study on a prospective cohort of patients with IBD, we demonstrated how the risk of orthorexia is high, 77%, and significantly higher than that observed in a control group. We have also documented how in the context of patients with IBD the presence of orthorexia is associated with lower BMI and history of previous surgery for IBD.

The role of nutrition in IBD, although not fully explored and known, is certainly relevant both as a factor involved in etiopathogenesis and in maintaining the disease remission state. For this reason, albeit not uniquely, guidelines suggest nutrition-focused approaches to the management of IBD. On the other hand, among patients with IBD, altered dietary perceptions and modifications are common. In this complex context, it is also important to assess the risk of eating disorders and among them, on the basis of our results, that of orthorexia nervosa.

To our knowledge, there are no studies that have assessed the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in patients with IBD, and our study is the first to document an elevated risk of orthorexia in these patients, with a significantly higher rate than in a control population. In the setting of digestive diseases, similar results have been obtained in a study conducted in women with celiac disease by Kujawowicz and coworkers [

22] . Another paper conducted on hungarian university students has addressed the risk of orthorexia in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Functional gastrointestinal symptoms were positively related to symptoms of orthorexia nervosa and emotional eating. The relationship between functional gastrointestinal symptoms and symptoms of orthorexia nervosa was partially mediated by health anxiety. [

23] In this setting another paper evidentiated a bidirectional relationship since IBS symptoms are more common in patients with established eating disorders. [

24]. Such bidirectionality with anxiety and depression has been already described in IBD at least for anorexia nervosa. [

25]. Anxiety and depression [

26], whose prevalence is estimated in IBD to be as high as 29–35% during remission and 60-80% during relapse, could be the drivers for patients with IBD to cross the “fine line” between an healthy eating belief aiming to

promote physical and mental health and orthorexia i.e. an obsessive and even detrimental research for “clean” food.

Our study also investigated whether demographic, clinical, social, as well as factors related to chronic IBD may be associated with a different risk of orthorexia. In this regard, we observed how IBD patients with orthorexia risk tend to have a lower BMI. We have documented also how the prevalence of orthorexia is significantly higher among those who have undergone surgery for IBD: this finding may depend on the fact that those undergoing surgery have a more severe history of IBD and a more challenging experiential experience that leads them to modify their diet as well. No difference was observed in relation to the type of IBD, severity of disease and type of therapy and sociocultural and occupational status. The last observation is rather surprising as the obsession for healthy foods (organic, no additives, no processing) could be expected to lead to more expensive food choices. A different interpretation is that patients of IBD have such a strong perception on the role of food to address the purchases in spite of their income.

Our study identifies a new form of disordered eating in a relatively large sample of patients of IBD that, though not yet classified in DSM –V, could be part of the spectrum of eating disorders. Identifying in a timely manner the development of an orthorexic behavior in IBD patients is mandatory to prevent nutritional consequences and the impact on quality of life. Food is not just about nourishment; it is also a source of pleasure, cultural heritage, and social connection.

Our study has some limitations, the largest of which relates to the fact that it was conducted on a cohort of patients with IBD followed in a tertiary referral center for IBD, most of whom were being treated with biologic drugs, and thus on a cohort that is not representative of all patients with IBD. Another limitation is the small sample size of the control population, which may interfere with the observed results and their interpretation. Finally, the differences in prevalence observed compared with the control population should be interpreted with great caution depending on the differences in age, BMI, and sociocultural status between patients with IBD and our control group.

Another limitation could be the choice of the cut-off for the diagnosis of orthorexia, which has been questioned in previous studies [

22]: however, the cut-off of 40 is the one

considered to be more predictive in a validation study (sensitivity 100.0%, specificity 73.6%, positive predictive value 17.6%, negative predictive value 100.0%)[

19]. Other research tools for the diagnosis of orthorexia are under investigation [

27]

In conclusion, our study showed that most patients with IBD (77%) have a risk of developing orthorexia and that this is associated with a lower BMI and a history of previous IBD surgery. Orthorexia can impact on the patient's psychological and social sphere, expose them to a high risk of developing severe nutritional deficiencies, and affect their quality of life. In addition, the high prevalence of orthorexia as well as other eating disorders support the need for an experienced dietitian within the multidisciplinary team in charge of the patient for the purpose of appropriate nutritional counseling. The skilled dietitian is expected to work side by side to a dedicated psychologist since anxiety and depression are often associated and cognitive behavioral therapy or participating in support groups or group therapy sessions could be helpful therapeutic strategies . Rebuilding a healthy relationship with food is essential for overall well-being.

Further high-quality studies in larger cohorts are warranted to confirm our results and evaluate the clinical impact of orthorexia in patients with IBD, the tools needed for its assessment, and its management. Long-term follow up of orthorexic IBD patients is necessary to investigate whether orthorexia evolves in classified eating disorders.

Conflict of Interest:

the authors declare no conflict if interests as far as concerns this study. Maria Cappello has served as lecturer and advisory board member for Takeda, Janssen, Galapagos, Pfizer, Ferring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maria Cappello.; methodology, Maria Cappello, Salvatore Petta and Francesca Maria Di Giorgio; formal analysis, Piero Luigi Almasio; investigation Stefania Pia Modica, Marica Saladino, Stefano Muscarella, Stefania Ciminnisi ; data curation, Maria Cappello e Francesca Maria Di Giorgio; writing—original draft preparation Francesca Maria Di Giorgio; writing, review and editing, Francesca Maria Di Giorgio, Salvatore Petta and Maria Cappello; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external fundings was received.

Ethics Statements

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and

approved by the Ethics Committee -Palermo 1 Approval n. 2/15.02.2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

the authors declare no conflict if interests as far as concerns this study. Maria Cappello has served as lecturer and advisory board member for Takeda, Janssen, Galapagos, Pfizer, Ferring.

References

- Roda G, Chien Ng S, Kotze PG, Argollo M, Panaccione R, Spinelli A, Kaser A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Crohn’s disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Apr 2;6(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Le Berre C, Honap S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2023 Aug 12;402(10401):571-584. [CrossRef]

- Guida, L.; Di Giorgio, F.M.; Busacca, A.; Carrozza, L.; Ciminnisi, S.; Almasio, P.L.; Di Marco, V.; Cappello, M. Perception of the Role of Food and Dietary Modifications in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Impact on Lifestyle. Nutrients 2021, 13, 759. [CrossRef]

- Berkley N. Limketkai, Rachel Sepulveda, Tressia Hing, Neha D. Shah, Monica Choe, David Limsui & Shamita Shah, Prevalence and factors associated with gluten sensitiviy in inflammatory bowel disease, Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 2018; 53:2,147- 151. [CrossRef]

- Levine A, Rhodes JM, Lindsay JO, et al. Dietary guidance from the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1381–1392. [CrossRef]

- Suskind DL, Lee D, Kim YM, et al. The specific carbohydrate diet and diet modification as induction therapy for pediatric Crohn’s disease: a randomized dietcontrolled trial. Nutrients 2020; 12:3749. [CrossRef]

- Lewis JD, Sandler R, Brotherton C, et al. A randomized trial comparing the specific carbohydrate diet to a Mediterranean diet in adults with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2021; S0016-5085(21):03069-9. [CrossRef]

- Forbes A, Escher J, Hébuterne X. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr 2017;36:321–347. [CrossRef]

- Yelencich E., Truong E., Widaman A.M., Pignotti G., Yang L., Jeon Y., Weber A.T., Shah R., Smith J., Sauk J.S., Limketkai B.N., Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Prevalent Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 24 2022 Jun;20(6):1282-1289.e1. [CrossRef]

- FM Di Giorgio, P. Melatti, S. Ciminnisi, M. Cappello. A Narrative Review on Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Need for Increased Awareness. Dietetics 2023, 2(2), 150-160. [CrossRef]

- Bratman, S.; Knight, D. Health Food Junkies. Orthorexia Nervosa: Overcoming the Obsession with Healthful Eating; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000.

- Brytek-Matera, A. Orthorexia nervosa—An eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder or disturbed eating habit? Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2012, 14, 55–60.

- Sellin, J. Dietary dilemmas, delusions, and decisions. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 1601–1604. [CrossRef]

- Varga, M.; Dukay-Szabó, S.; Túry, F.; van Furth, E.F. Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders 2013, 18, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Barthels, F.; Meyer, F.; Pietrowsky, R. Düesseldorf orthorexia scale–construction and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring orthorexic eating behavior. Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 44, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Setnick, J. The Eating Disorders Clinical Pocket Guide: Quick Reference for Healthcare Providers, 2nd ed.; Snack Time Press: 2015.

- Dunn, T.M.; Bratman, S. On orthorexia nervosa: A review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat. Behav. 2016, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.A.; Caltabiano, M.L. The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017, 22, 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Donini L.M., Marsili D., Graziani M.P., Imbriale M.,Cannella C. Orthorexia nervosa: Validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eating Weight Disord. 2005; 10: e28- e32. [CrossRef]

- Stochel, M.; Janas-Kozik, M.; Zejda, J.; Hyrnik, J.; Jelonek, I.; Siwiec, A. Validation of ORTO-15 Questionnaire in the group of urban youth aged 15-21. Psychiatr. Pol. 2015, 49, 119–134. [CrossRef]

- Agopyan, A.; Kenger, E.B.; Kermen, S.; Ulker, M.T.; Uzsoy, M.A.; Yetgin, M.K. The relationship between orthorexia nervosa and body composition in female students of the nutrition and dietetics department. Eat. Weight Disord. 2019, 24, 257–266. [CrossRef]

- Kujawowicz K, Mirończuk-Chodakowska I, Witkowska A.M. Dietary behavior and risk of orthorexia in women with celiac disease. Nutrients 2022; 14(4):904. [CrossRef]

- Gajdos P, Román N, Toth-Kiraly I, Rigó A. Functional gastrointestinal symptoms and increased risk for orthorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity (2022) 27:1113–1121. [CrossRef]

- Abrahama S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 70 (2011) 372–377. [CrossRef]

- Hedman, A.; Breithaupt, L.; Hübel, C.; Thornton, L.M.; Tillander, A.; Norring, C.; Birgegård, A.; Larsson, H.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Sävendahl, L.; et al. Bidirectional relationship between eating disorders and autoimmune diseases. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 803–812. [CrossRef]

- Sajadinejad M.S., Asgari K.,Molavi H., Kalantari M., Adibi P. Psychological Issues in Inflammatory Bowel Disease:An Overview. Gastroenterology Research and Practice Volume 2012, Article ID 106502, 11 pages. [CrossRef]

- Barrada, J.R.; Roncero, M. Bidimensional Structure of the Orthorexia: Development and Initial Validation of a New Instrument. Ann. Psicol. 2018, 34, 283–291. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).